User login

Stents Fixed Dialysis Graft/Fistula Pseudoaneurysms

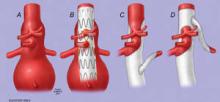

LAS VEGAS -- Percutaneous covered stents safely and effectively bypass and seal off pseudoaneurysms in arteriovenous grafts and fistulas, preventing rupture, prolonging hemodialysis access, and eliminating the need for open surgical repair, a prospective study of 24 patients has found.

"Endograft exclusion of PSAs [pseudoaneurysms] is a practical approach to solving a not uncommonly encountered clinical problem in this complex patient population. Patients avoid complications related to [surgery], and are able to maintain an uninterrupted dialysis pattern" without the use of a central venous catheter, lead investigator Alison Kinning said at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery.

Twenty of the patients had arteriovenous grafts, four had arteriovenous fistulas, and all had at least one pseudoaneurysm. The patients were stented with Fluency e-polytetrafluoroethylene–covered nitinol stents using a bareback technique.

A 6-French sheath was placed after removal of the stent delivery catheter, and angioplasty was used in order to pleat out and fix the stent in place, with angioplasty for outflow stenosis also done as needed. Blood was drawn out of the aneurysm after the stent was in place in order to relieve skin tension.

"We allowed immediate [dialysis] cannulation, including the stented segment, following endograft placement. We did mark the center of the stent so as to avoid cannulation [of its ends]," noted Ms. Kinning, a third-year medical student at the American University of the Caribbean in St. Maarten.

Primary assisted patency was 100% in the 20 patients who completed a 2-month follow-up and in the 13 who completed a 6-month follow-up. The mean duration of patency was 17.6 months, and the longest duration of patency was 6 years, 4 months.

However, after 2 months one patient asked to have the stent removed because of pain, and two patients were restented after their initial stents fractured.

Five stented grafts had to be removed after a mean of 2.4 months because of infection. The cause of the infections is uncertain, but these probably occurred because of repeated cannulations, diabetes, poor personal hygiene, or other factors.

"Sometimes, the infection may have already started [before stenting], but you’ve at least prevented the [graft] from rupturing. Sometimes the stent will help you control an emergent or threatening situation and give you time to plan a repair or bypass if needed," said coauthor Dr. Wayne Kinning, a vascular surgeon in Flint, Mich., and Ms. Kinning’s father.

A handful of other studies have supported the use of stents in order to treat pseudoaneurysms.

One such study found that infections were associated with skin erosion over the aneurysm. In this retrospective review of medical records by Dr. Aamir Shah, patients with a PSA underwent endovascular repair using a stent graft. The indications for repair included PSA with symptoms, PSA with skin erosion, PSA with failed hemodialysis, and PSA after balloon angioplasty of a stenosis. (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jjvs.2011.10.126]).

The procedure "probably will become increasingly recommended. I think that’s the shift that’s happening," said Dr. Kinning.

Ms. Kinning and Dr. Kinning said they had no relevant disclosures.

We have also been using this technique to salvage these grafts and fistulae. It is especially useful as a stop-gap measure. We have our own outpatient in-office suite and so we can treat a patient who comes to the office exsanguinating, place the graft, control the hemorrhage and then electively work the patient up for further treatment as necessary.

Dr. Russell H. Samson is Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery (Vascular) Florida State University Medical School, and Attending Vascular Surgeon, Sarasota Vascular Specialists. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

We have also been using this technique to salvage these grafts and fistulae. It is especially useful as a stop-gap measure. We have our own outpatient in-office suite and so we can treat a patient who comes to the office exsanguinating, place the graft, control the hemorrhage and then electively work the patient up for further treatment as necessary.

Dr. Russell H. Samson is Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery (Vascular) Florida State University Medical School, and Attending Vascular Surgeon, Sarasota Vascular Specialists. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

We have also been using this technique to salvage these grafts and fistulae. It is especially useful as a stop-gap measure. We have our own outpatient in-office suite and so we can treat a patient who comes to the office exsanguinating, place the graft, control the hemorrhage and then electively work the patient up for further treatment as necessary.

Dr. Russell H. Samson is Clinical Associate Professor of Surgery (Vascular) Florida State University Medical School, and Attending Vascular Surgeon, Sarasota Vascular Specialists. He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

LAS VEGAS -- Percutaneous covered stents safely and effectively bypass and seal off pseudoaneurysms in arteriovenous grafts and fistulas, preventing rupture, prolonging hemodialysis access, and eliminating the need for open surgical repair, a prospective study of 24 patients has found.

"Endograft exclusion of PSAs [pseudoaneurysms] is a practical approach to solving a not uncommonly encountered clinical problem in this complex patient population. Patients avoid complications related to [surgery], and are able to maintain an uninterrupted dialysis pattern" without the use of a central venous catheter, lead investigator Alison Kinning said at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery.

Twenty of the patients had arteriovenous grafts, four had arteriovenous fistulas, and all had at least one pseudoaneurysm. The patients were stented with Fluency e-polytetrafluoroethylene–covered nitinol stents using a bareback technique.

A 6-French sheath was placed after removal of the stent delivery catheter, and angioplasty was used in order to pleat out and fix the stent in place, with angioplasty for outflow stenosis also done as needed. Blood was drawn out of the aneurysm after the stent was in place in order to relieve skin tension.

"We allowed immediate [dialysis] cannulation, including the stented segment, following endograft placement. We did mark the center of the stent so as to avoid cannulation [of its ends]," noted Ms. Kinning, a third-year medical student at the American University of the Caribbean in St. Maarten.

Primary assisted patency was 100% in the 20 patients who completed a 2-month follow-up and in the 13 who completed a 6-month follow-up. The mean duration of patency was 17.6 months, and the longest duration of patency was 6 years, 4 months.

However, after 2 months one patient asked to have the stent removed because of pain, and two patients were restented after their initial stents fractured.

Five stented grafts had to be removed after a mean of 2.4 months because of infection. The cause of the infections is uncertain, but these probably occurred because of repeated cannulations, diabetes, poor personal hygiene, or other factors.

"Sometimes, the infection may have already started [before stenting], but you’ve at least prevented the [graft] from rupturing. Sometimes the stent will help you control an emergent or threatening situation and give you time to plan a repair or bypass if needed," said coauthor Dr. Wayne Kinning, a vascular surgeon in Flint, Mich., and Ms. Kinning’s father.

A handful of other studies have supported the use of stents in order to treat pseudoaneurysms.

One such study found that infections were associated with skin erosion over the aneurysm. In this retrospective review of medical records by Dr. Aamir Shah, patients with a PSA underwent endovascular repair using a stent graft. The indications for repair included PSA with symptoms, PSA with skin erosion, PSA with failed hemodialysis, and PSA after balloon angioplasty of a stenosis. (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jjvs.2011.10.126]).

The procedure "probably will become increasingly recommended. I think that’s the shift that’s happening," said Dr. Kinning.

Ms. Kinning and Dr. Kinning said they had no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS -- Percutaneous covered stents safely and effectively bypass and seal off pseudoaneurysms in arteriovenous grafts and fistulas, preventing rupture, prolonging hemodialysis access, and eliminating the need for open surgical repair, a prospective study of 24 patients has found.

"Endograft exclusion of PSAs [pseudoaneurysms] is a practical approach to solving a not uncommonly encountered clinical problem in this complex patient population. Patients avoid complications related to [surgery], and are able to maintain an uninterrupted dialysis pattern" without the use of a central venous catheter, lead investigator Alison Kinning said at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery.

Twenty of the patients had arteriovenous grafts, four had arteriovenous fistulas, and all had at least one pseudoaneurysm. The patients were stented with Fluency e-polytetrafluoroethylene–covered nitinol stents using a bareback technique.

A 6-French sheath was placed after removal of the stent delivery catheter, and angioplasty was used in order to pleat out and fix the stent in place, with angioplasty for outflow stenosis also done as needed. Blood was drawn out of the aneurysm after the stent was in place in order to relieve skin tension.

"We allowed immediate [dialysis] cannulation, including the stented segment, following endograft placement. We did mark the center of the stent so as to avoid cannulation [of its ends]," noted Ms. Kinning, a third-year medical student at the American University of the Caribbean in St. Maarten.

Primary assisted patency was 100% in the 20 patients who completed a 2-month follow-up and in the 13 who completed a 6-month follow-up. The mean duration of patency was 17.6 months, and the longest duration of patency was 6 years, 4 months.

However, after 2 months one patient asked to have the stent removed because of pain, and two patients were restented after their initial stents fractured.

Five stented grafts had to be removed after a mean of 2.4 months because of infection. The cause of the infections is uncertain, but these probably occurred because of repeated cannulations, diabetes, poor personal hygiene, or other factors.

"Sometimes, the infection may have already started [before stenting], but you’ve at least prevented the [graft] from rupturing. Sometimes the stent will help you control an emergent or threatening situation and give you time to plan a repair or bypass if needed," said coauthor Dr. Wayne Kinning, a vascular surgeon in Flint, Mich., and Ms. Kinning’s father.

A handful of other studies have supported the use of stents in order to treat pseudoaneurysms.

One such study found that infections were associated with skin erosion over the aneurysm. In this retrospective review of medical records by Dr. Aamir Shah, patients with a PSA underwent endovascular repair using a stent graft. The indications for repair included PSA with symptoms, PSA with skin erosion, PSA with failed hemodialysis, and PSA after balloon angioplasty of a stenosis. (J. Vasc. Surg. 2012 [doi:10.1016/j.jjvs.2011.10.126]).

The procedure "probably will become increasingly recommended. I think that’s the shift that’s happening," said Dr. Kinning.

Ms. Kinning and Dr. Kinning said they had no relevant disclosures.

Major Finding: Following stenting of hemodialysis graft pseudoaneurysms, primary assisted patency was 100% in the 20 patients who completed a 2-month follow-up and in the 13 who completed a 6-month follow-up.

Data Source: A prospective series of 24 patients was studied.

Disclosures: Ms. Kinning and Dr. Kinning said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

U.S. Fibromuscular Dysplasia Registry Yields Clues

MIAMI BEACH – The mystery shrouding fibromuscular dysplasia, a clinically important and surprisingly prevalent vascular disease of unknown etiology, began to lift with initial findings from 339 patients enrolled in the first U.S. registry for the disease. Baseline observations from the U.S. Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMD), which enrolled its first patient in 2008 and currently has women as 91% of enrolled patients, show that the disease first occurs across a broad swath of age groups, with an age at first diagnosis ranging from 5 to 83 years old. In addition to the distinctive "string of beads" arterial fibrosis appearance that defines the disease and is apparent on imaging, and which usually occurs in the renal or carotid artery, or both, 19% of patients also had a dissection in an artery somewhere in their body (14% with a dissection in a carotid artery) and 17% had an arterial aneurysm somewhere (5% with a renal artery aneurysm and 4% with a carotid aneurysm).

These dissection and aneurysm prevalence rates were not appreciated to run so high in FMD patients. "It suggests a diffuse arteriopathy that can present in several different ways," Dr. Jeffrey W. Olin said at ISET 2012.

Another notable finding was that, besides hypertension, which was the most common presenting manifestation of FMD (seen in 66% of the registry patients at initial diagnosis), other common presenting symptoms included significant, often migraine-like headache in 53%, pulsatile tinnitus (a whooshing sound patients hear) in 30%, and dizziness in 28%. The high prevalence of headache in FMD was "first reported 30 years ago, but sort of got lost," Dr. Olin said in an interview. "A patient can have normal blood pressure and normal-appearing carotid and renal arteries but have terrible headaches and have FMD. Why? We don’t know. We have no idea what causes the headaches," said Dr. Olin, director of vascular medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Four percent of the registry patients had no symptoms on presentation; physicians found their FMD incidentally during imaging for other reasons.

Other flags to trigger suspicion of FMD include hypertension that begins before age 35 (although it can also start later in life), treatment-resistant hypertension, epigastric bruit and hypertension, renal infarction, cervical bruit in a patient less than 60 years old, transient ischemic attack or stroke in a patient less than 60 years old, or an aortic aneurysm in a patient less than 60 years old.

Perhaps the most surprising new finding so far from the registry is evidence for a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, with 81% of first- or second-degree relatives of FMD patients having hypertension, 59% with hyperlipidemia, 53% with a history of a stroke, 22% with an aneurysm, and 21% with a history of sudden death. The prevalence of a first- or second-degree relative also having a diagnosis of FMD was 7%, not much higher than the estimated 4% prevalence of FMD in the general population.

Dr. Olin and his associates from the registry hypothesize that patients who develop FMD have an as-yet unidentified genetic predisposition that interacts with an environmental trigger. His hope is that, by continuing to expand the registry and by receiving substantially more research support than FMD now gets, a more concerted research effort can address the genetic questions raised by the family-history findings.

Current treatment of FMD is symptom driven and usually focuses on trying to resolve patients’ hypertension, which is often treatment resistant.

"FMD is potentially treatable for hypertension," with endovascular treatment of affected renal arteries the standard intervention for patients with resistant hypertension, Dr. Robert A. Lookstein of Mount Sinai said in a separate talk at the meeting. Hypertension cure rates from balloon angioplasty, however, are "surprisingly low" – 45% in one meta-analysis – probably because of suboptimal interventional treatment.

Assessing a patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and a pressure wire provides the key to successful resolution of hypertension by renal-artery angioplasty in FMD patients.

These two techniques, especially pressure-wire measurements, allow the operator to assess the patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment to determine whether the intervention is having a meaningful effect. "You can’t tell [whether the angioplasty produced benefit] by the angiography appearance alone," he cautioned. "You need to be compulsive with IVUS and measuring pressure gradients to determine where to start treatment and when to stop."

The U.S. Registry for FMD began with seven U.S. centers enrolling patients and now involves 10 centers and has enrolled more than 500 patients. The first 339 enrollees included 44% who were patients at the Cleveland Clinic and 20% who were patients at Mount Sinai. The average age of the enrolled patients at first symptom appearance was 47 years old; first diagnosis was an average of more than 4 years later, at an average age of 52 years old.

Vascular bed involvement among the first registry patients included one or both renal arteries in 69%, at least one extracranial carotid in 62%, vertebral arteries in 19%, and mesenteric arteries in 12%. At the time of enrollment, 7% of patients had a history of coronary artery disease and 10% had a history of stroke. The arterial fibrosis characteristic of FMD notably appears in portions of the renal and carotid arteries where atherosclerotic disease usually does not occur – in the distal renal artery and in the distal carotid, "higher than physicians usually look when they do carotid ultrasound" examinations, Dr. Olin said.

When he finds carotid fibrosis, Dr. Olin starts those patients on a daily aspirin, although the benefit of this strategy hasn’t been proven. If carotid lesions are substantial, treatment by angioplasty is possible; carotid stenting is not used on FMD patients, nor is endarterectomy, as there is no atherosclerotic plaque to remove, he said.

Dr. Olin has been a consultant to Merck, and chairs the advisory board of the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America. Dr. Lookstein said he has been a consultant to Medrad and Cordis.

MIAMI BEACH – The mystery shrouding fibromuscular dysplasia, a clinically important and surprisingly prevalent vascular disease of unknown etiology, began to lift with initial findings from 339 patients enrolled in the first U.S. registry for the disease. Baseline observations from the U.S. Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMD), which enrolled its first patient in 2008 and currently has women as 91% of enrolled patients, show that the disease first occurs across a broad swath of age groups, with an age at first diagnosis ranging from 5 to 83 years old. In addition to the distinctive "string of beads" arterial fibrosis appearance that defines the disease and is apparent on imaging, and which usually occurs in the renal or carotid artery, or both, 19% of patients also had a dissection in an artery somewhere in their body (14% with a dissection in a carotid artery) and 17% had an arterial aneurysm somewhere (5% with a renal artery aneurysm and 4% with a carotid aneurysm).

These dissection and aneurysm prevalence rates were not appreciated to run so high in FMD patients. "It suggests a diffuse arteriopathy that can present in several different ways," Dr. Jeffrey W. Olin said at ISET 2012.

Another notable finding was that, besides hypertension, which was the most common presenting manifestation of FMD (seen in 66% of the registry patients at initial diagnosis), other common presenting symptoms included significant, often migraine-like headache in 53%, pulsatile tinnitus (a whooshing sound patients hear) in 30%, and dizziness in 28%. The high prevalence of headache in FMD was "first reported 30 years ago, but sort of got lost," Dr. Olin said in an interview. "A patient can have normal blood pressure and normal-appearing carotid and renal arteries but have terrible headaches and have FMD. Why? We don’t know. We have no idea what causes the headaches," said Dr. Olin, director of vascular medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Four percent of the registry patients had no symptoms on presentation; physicians found their FMD incidentally during imaging for other reasons.

Other flags to trigger suspicion of FMD include hypertension that begins before age 35 (although it can also start later in life), treatment-resistant hypertension, epigastric bruit and hypertension, renal infarction, cervical bruit in a patient less than 60 years old, transient ischemic attack or stroke in a patient less than 60 years old, or an aortic aneurysm in a patient less than 60 years old.

Perhaps the most surprising new finding so far from the registry is evidence for a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, with 81% of first- or second-degree relatives of FMD patients having hypertension, 59% with hyperlipidemia, 53% with a history of a stroke, 22% with an aneurysm, and 21% with a history of sudden death. The prevalence of a first- or second-degree relative also having a diagnosis of FMD was 7%, not much higher than the estimated 4% prevalence of FMD in the general population.

Dr. Olin and his associates from the registry hypothesize that patients who develop FMD have an as-yet unidentified genetic predisposition that interacts with an environmental trigger. His hope is that, by continuing to expand the registry and by receiving substantially more research support than FMD now gets, a more concerted research effort can address the genetic questions raised by the family-history findings.

Current treatment of FMD is symptom driven and usually focuses on trying to resolve patients’ hypertension, which is often treatment resistant.

"FMD is potentially treatable for hypertension," with endovascular treatment of affected renal arteries the standard intervention for patients with resistant hypertension, Dr. Robert A. Lookstein of Mount Sinai said in a separate talk at the meeting. Hypertension cure rates from balloon angioplasty, however, are "surprisingly low" – 45% in one meta-analysis – probably because of suboptimal interventional treatment.

Assessing a patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and a pressure wire provides the key to successful resolution of hypertension by renal-artery angioplasty in FMD patients.

These two techniques, especially pressure-wire measurements, allow the operator to assess the patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment to determine whether the intervention is having a meaningful effect. "You can’t tell [whether the angioplasty produced benefit] by the angiography appearance alone," he cautioned. "You need to be compulsive with IVUS and measuring pressure gradients to determine where to start treatment and when to stop."

The U.S. Registry for FMD began with seven U.S. centers enrolling patients and now involves 10 centers and has enrolled more than 500 patients. The first 339 enrollees included 44% who were patients at the Cleveland Clinic and 20% who were patients at Mount Sinai. The average age of the enrolled patients at first symptom appearance was 47 years old; first diagnosis was an average of more than 4 years later, at an average age of 52 years old.

Vascular bed involvement among the first registry patients included one or both renal arteries in 69%, at least one extracranial carotid in 62%, vertebral arteries in 19%, and mesenteric arteries in 12%. At the time of enrollment, 7% of patients had a history of coronary artery disease and 10% had a history of stroke. The arterial fibrosis characteristic of FMD notably appears in portions of the renal and carotid arteries where atherosclerotic disease usually does not occur – in the distal renal artery and in the distal carotid, "higher than physicians usually look when they do carotid ultrasound" examinations, Dr. Olin said.

When he finds carotid fibrosis, Dr. Olin starts those patients on a daily aspirin, although the benefit of this strategy hasn’t been proven. If carotid lesions are substantial, treatment by angioplasty is possible; carotid stenting is not used on FMD patients, nor is endarterectomy, as there is no atherosclerotic plaque to remove, he said.

Dr. Olin has been a consultant to Merck, and chairs the advisory board of the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America. Dr. Lookstein said he has been a consultant to Medrad and Cordis.

MIAMI BEACH – The mystery shrouding fibromuscular dysplasia, a clinically important and surprisingly prevalent vascular disease of unknown etiology, began to lift with initial findings from 339 patients enrolled in the first U.S. registry for the disease. Baseline observations from the U.S. Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMD), which enrolled its first patient in 2008 and currently has women as 91% of enrolled patients, show that the disease first occurs across a broad swath of age groups, with an age at first diagnosis ranging from 5 to 83 years old. In addition to the distinctive "string of beads" arterial fibrosis appearance that defines the disease and is apparent on imaging, and which usually occurs in the renal or carotid artery, or both, 19% of patients also had a dissection in an artery somewhere in their body (14% with a dissection in a carotid artery) and 17% had an arterial aneurysm somewhere (5% with a renal artery aneurysm and 4% with a carotid aneurysm).

These dissection and aneurysm prevalence rates were not appreciated to run so high in FMD patients. "It suggests a diffuse arteriopathy that can present in several different ways," Dr. Jeffrey W. Olin said at ISET 2012.

Another notable finding was that, besides hypertension, which was the most common presenting manifestation of FMD (seen in 66% of the registry patients at initial diagnosis), other common presenting symptoms included significant, often migraine-like headache in 53%, pulsatile tinnitus (a whooshing sound patients hear) in 30%, and dizziness in 28%. The high prevalence of headache in FMD was "first reported 30 years ago, but sort of got lost," Dr. Olin said in an interview. "A patient can have normal blood pressure and normal-appearing carotid and renal arteries but have terrible headaches and have FMD. Why? We don’t know. We have no idea what causes the headaches," said Dr. Olin, director of vascular medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. Four percent of the registry patients had no symptoms on presentation; physicians found their FMD incidentally during imaging for other reasons.

Other flags to trigger suspicion of FMD include hypertension that begins before age 35 (although it can also start later in life), treatment-resistant hypertension, epigastric bruit and hypertension, renal infarction, cervical bruit in a patient less than 60 years old, transient ischemic attack or stroke in a patient less than 60 years old, or an aortic aneurysm in a patient less than 60 years old.

Perhaps the most surprising new finding so far from the registry is evidence for a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, with 81% of first- or second-degree relatives of FMD patients having hypertension, 59% with hyperlipidemia, 53% with a history of a stroke, 22% with an aneurysm, and 21% with a history of sudden death. The prevalence of a first- or second-degree relative also having a diagnosis of FMD was 7%, not much higher than the estimated 4% prevalence of FMD in the general population.

Dr. Olin and his associates from the registry hypothesize that patients who develop FMD have an as-yet unidentified genetic predisposition that interacts with an environmental trigger. His hope is that, by continuing to expand the registry and by receiving substantially more research support than FMD now gets, a more concerted research effort can address the genetic questions raised by the family-history findings.

Current treatment of FMD is symptom driven and usually focuses on trying to resolve patients’ hypertension, which is often treatment resistant.

"FMD is potentially treatable for hypertension," with endovascular treatment of affected renal arteries the standard intervention for patients with resistant hypertension, Dr. Robert A. Lookstein of Mount Sinai said in a separate talk at the meeting. Hypertension cure rates from balloon angioplasty, however, are "surprisingly low" – 45% in one meta-analysis – probably because of suboptimal interventional treatment.

Assessing a patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and a pressure wire provides the key to successful resolution of hypertension by renal-artery angioplasty in FMD patients.

These two techniques, especially pressure-wire measurements, allow the operator to assess the patient’s renal arteries before and during treatment to determine whether the intervention is having a meaningful effect. "You can’t tell [whether the angioplasty produced benefit] by the angiography appearance alone," he cautioned. "You need to be compulsive with IVUS and measuring pressure gradients to determine where to start treatment and when to stop."

The U.S. Registry for FMD began with seven U.S. centers enrolling patients and now involves 10 centers and has enrolled more than 500 patients. The first 339 enrollees included 44% who were patients at the Cleveland Clinic and 20% who were patients at Mount Sinai. The average age of the enrolled patients at first symptom appearance was 47 years old; first diagnosis was an average of more than 4 years later, at an average age of 52 years old.

Vascular bed involvement among the first registry patients included one or both renal arteries in 69%, at least one extracranial carotid in 62%, vertebral arteries in 19%, and mesenteric arteries in 12%. At the time of enrollment, 7% of patients had a history of coronary artery disease and 10% had a history of stroke. The arterial fibrosis characteristic of FMD notably appears in portions of the renal and carotid arteries where atherosclerotic disease usually does not occur – in the distal renal artery and in the distal carotid, "higher than physicians usually look when they do carotid ultrasound" examinations, Dr. Olin said.

When he finds carotid fibrosis, Dr. Olin starts those patients on a daily aspirin, although the benefit of this strategy hasn’t been proven. If carotid lesions are substantial, treatment by angioplasty is possible; carotid stenting is not used on FMD patients, nor is endarterectomy, as there is no atherosclerotic plaque to remove, he said.

Dr. Olin has been a consultant to Merck, and chairs the advisory board of the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America. Dr. Lookstein said he has been a consultant to Medrad and Cordis.

Major Finding: The most common presenting symptoms in patients with fibromuscular dysplasia were hypertension in 66%, headache in 53%, pulsatile tinnitus in 30%, and dizziness in 28%.

Data Source: Baseline findings from the first 339 patients enrolled in the U.S. Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia.

Disclosures: Dr. Olin said that he has been a consultant to Merck, and that he chairs the advisory board of the Fibromuscular Dysplasia Society of America. Dr. Lookstein said that he has been a consultant to Medrad and Cordis.

IVUS Seen As Aid to Aortic Endografting

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Six years of having intravascular ultrasound guidance available during thoracic and abdominal endografting procedures for aortic pathologies has convinced one surgeon that it’s a sometimes necessary, sometimes complementary imaging modality – not an expensive, redundant novelty.

Among 449 cases of aortic endografting for aneurysmal, dissection, or traumatic pathologies, Dr. Martin R. Back chose to use intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance in 194 cases (43%), he reported at the meeting. He used IVUS guidance in 76 (66%) of 115 thoracic cases and 118 (35%) of 334 abdominal cases.

IVUS guidance may replace most maneuvers that currently require contrast angiography during endovascular aneurysm repair and thoracic endovascular aortic repair, said Dr. Back, professor of surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

He found IVUS guidance indispensable during treatment of acute aortic dissections, using it in all 25 cases. It also was especially helpful in 8 (57%) of 14 hybrid thoracoabdominal cases, he said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"I found it particularly useful in these cases to turn these into a single-stage procedure" with visceral branching done up front, endografting done primarily with IVUS guidance, and very-low-volume contrast used to assess completion of the repair, he said.

IVUS use reduced the volume of contrast needed during abdominal cases and significantly reduced the risk of worsening renal function after aortic endografting in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency.

Average contrast dye volume during abdominal cases was 47 mL in IVUS-guided cases and 92 mL in cases without IVUS, a significant difference. Procedural contrast dye volume was marginally lower with IVUS use compared with no IVUS in thoracic cases – 91 mL vs. 106 mL, respectively.

Among thoracic cases, 26 of 115 patients (23%) had existing chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 22 of these 26 patients (85%). Among abdominal cases, 70 of 334 patients (21%) had chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 43 of these 70 cases (62%).

Among 89 patients with preoperative chronic renal insufficiency and complete follow-up data 30 days after the procedure, renal function worsened in 7 of 60 patients (12%) who had IVUS guidance and 9 of 29 patients (31%) with no IVUS, a significant difference. Worsening renal function was defined as greater than a 50% increase in baseline creatinine or dialysis by day 30.

"IVUS use cuts down on dye use and spares kidneys in that higher-risk population," he said.

Among 331 patients without preexisting chronic renal insufficiency who had 30 days of follow-up data, renal function worsened in 9 (8%) of 107 patients who had IVUS guidance and in 12 (5%) of 224 patients without IVUS, which was not significantly different between groups.

"This is not really a diagnostic tool but can be used as an intraprocedural guidance tool with fluoroscopy to supplant the need for angiographic injections throughout the performance of an endovascular aortic intervention," he said. In general, IVUS guidance appeared to be safe and accurate for endografting, he said. In a random sample of 25 cases with IVUS guidance and 51 cases without IVUS in patients with similar-sized aneurysms and fixation lengths, measurements from the lowest renal artery to the endograft device and from the hypogastric arteries to the end of the device were similar in accuracy, Dr. Back said.

Cost is an issue, with IVUS catheters being approximately $500 each. "I’m not advocating for all these patients" to have IVUS-guided endografting, but there are "subgroups here that I think really benefit from its use," he said.

Dr. Back reported being a paid trainer and speaker for Volcano Corp., which markets the IVUS equipment that he used in his case series.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Six years of having intravascular ultrasound guidance available during thoracic and abdominal endografting procedures for aortic pathologies has convinced one surgeon that it’s a sometimes necessary, sometimes complementary imaging modality – not an expensive, redundant novelty.

Among 449 cases of aortic endografting for aneurysmal, dissection, or traumatic pathologies, Dr. Martin R. Back chose to use intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance in 194 cases (43%), he reported at the meeting. He used IVUS guidance in 76 (66%) of 115 thoracic cases and 118 (35%) of 334 abdominal cases.

IVUS guidance may replace most maneuvers that currently require contrast angiography during endovascular aneurysm repair and thoracic endovascular aortic repair, said Dr. Back, professor of surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

He found IVUS guidance indispensable during treatment of acute aortic dissections, using it in all 25 cases. It also was especially helpful in 8 (57%) of 14 hybrid thoracoabdominal cases, he said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"I found it particularly useful in these cases to turn these into a single-stage procedure" with visceral branching done up front, endografting done primarily with IVUS guidance, and very-low-volume contrast used to assess completion of the repair, he said.

IVUS use reduced the volume of contrast needed during abdominal cases and significantly reduced the risk of worsening renal function after aortic endografting in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency.

Average contrast dye volume during abdominal cases was 47 mL in IVUS-guided cases and 92 mL in cases without IVUS, a significant difference. Procedural contrast dye volume was marginally lower with IVUS use compared with no IVUS in thoracic cases – 91 mL vs. 106 mL, respectively.

Among thoracic cases, 26 of 115 patients (23%) had existing chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 22 of these 26 patients (85%). Among abdominal cases, 70 of 334 patients (21%) had chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 43 of these 70 cases (62%).

Among 89 patients with preoperative chronic renal insufficiency and complete follow-up data 30 days after the procedure, renal function worsened in 7 of 60 patients (12%) who had IVUS guidance and 9 of 29 patients (31%) with no IVUS, a significant difference. Worsening renal function was defined as greater than a 50% increase in baseline creatinine or dialysis by day 30.

"IVUS use cuts down on dye use and spares kidneys in that higher-risk population," he said.

Among 331 patients without preexisting chronic renal insufficiency who had 30 days of follow-up data, renal function worsened in 9 (8%) of 107 patients who had IVUS guidance and in 12 (5%) of 224 patients without IVUS, which was not significantly different between groups.

"This is not really a diagnostic tool but can be used as an intraprocedural guidance tool with fluoroscopy to supplant the need for angiographic injections throughout the performance of an endovascular aortic intervention," he said. In general, IVUS guidance appeared to be safe and accurate for endografting, he said. In a random sample of 25 cases with IVUS guidance and 51 cases without IVUS in patients with similar-sized aneurysms and fixation lengths, measurements from the lowest renal artery to the endograft device and from the hypogastric arteries to the end of the device were similar in accuracy, Dr. Back said.

Cost is an issue, with IVUS catheters being approximately $500 each. "I’m not advocating for all these patients" to have IVUS-guided endografting, but there are "subgroups here that I think really benefit from its use," he said.

Dr. Back reported being a paid trainer and speaker for Volcano Corp., which markets the IVUS equipment that he used in his case series.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Six years of having intravascular ultrasound guidance available during thoracic and abdominal endografting procedures for aortic pathologies has convinced one surgeon that it’s a sometimes necessary, sometimes complementary imaging modality – not an expensive, redundant novelty.

Among 449 cases of aortic endografting for aneurysmal, dissection, or traumatic pathologies, Dr. Martin R. Back chose to use intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance in 194 cases (43%), he reported at the meeting. He used IVUS guidance in 76 (66%) of 115 thoracic cases and 118 (35%) of 334 abdominal cases.

IVUS guidance may replace most maneuvers that currently require contrast angiography during endovascular aneurysm repair and thoracic endovascular aortic repair, said Dr. Back, professor of surgery at the University of South Florida, Tampa.

He found IVUS guidance indispensable during treatment of acute aortic dissections, using it in all 25 cases. It also was especially helpful in 8 (57%) of 14 hybrid thoracoabdominal cases, he said at the annual meeting of the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery.

"I found it particularly useful in these cases to turn these into a single-stage procedure" with visceral branching done up front, endografting done primarily with IVUS guidance, and very-low-volume contrast used to assess completion of the repair, he said.

IVUS use reduced the volume of contrast needed during abdominal cases and significantly reduced the risk of worsening renal function after aortic endografting in patients with preexisting renal insufficiency.

Average contrast dye volume during abdominal cases was 47 mL in IVUS-guided cases and 92 mL in cases without IVUS, a significant difference. Procedural contrast dye volume was marginally lower with IVUS use compared with no IVUS in thoracic cases – 91 mL vs. 106 mL, respectively.

Among thoracic cases, 26 of 115 patients (23%) had existing chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 22 of these 26 patients (85%). Among abdominal cases, 70 of 334 patients (21%) had chronic renal insufficiency, and he used IVUS guidance in 43 of these 70 cases (62%).

Among 89 patients with preoperative chronic renal insufficiency and complete follow-up data 30 days after the procedure, renal function worsened in 7 of 60 patients (12%) who had IVUS guidance and 9 of 29 patients (31%) with no IVUS, a significant difference. Worsening renal function was defined as greater than a 50% increase in baseline creatinine or dialysis by day 30.

"IVUS use cuts down on dye use and spares kidneys in that higher-risk population," he said.

Among 331 patients without preexisting chronic renal insufficiency who had 30 days of follow-up data, renal function worsened in 9 (8%) of 107 patients who had IVUS guidance and in 12 (5%) of 224 patients without IVUS, which was not significantly different between groups.

"This is not really a diagnostic tool but can be used as an intraprocedural guidance tool with fluoroscopy to supplant the need for angiographic injections throughout the performance of an endovascular aortic intervention," he said. In general, IVUS guidance appeared to be safe and accurate for endografting, he said. In a random sample of 25 cases with IVUS guidance and 51 cases without IVUS in patients with similar-sized aneurysms and fixation lengths, measurements from the lowest renal artery to the endograft device and from the hypogastric arteries to the end of the device were similar in accuracy, Dr. Back said.

Cost is an issue, with IVUS catheters being approximately $500 each. "I’m not advocating for all these patients" to have IVUS-guided endografting, but there are "subgroups here that I think really benefit from its use," he said.

Dr. Back reported being a paid trainer and speaker for Volcano Corp., which markets the IVUS equipment that he used in his case series.

Major Finding: One surgeon found intravascular ultrasound guidance helpful in 43% (194) of 449 endovascular aortic endografting cases.

Data Source: This was a retrospective study of 449 consecutive thoracic and abdominal endografting procedures by one surgeon for aneurysmal, dissection, and traumatic pathologies.

Disclosures: Dr. Back reported being a paid trainer and speaker for Volcano Corp., which markets the IVUS equipment that he used in his case series.

Local, Regional Anesthesia Surpass General for AAA EVAR

MIAMI BEACH – Both local anesthesia and regional anesthesia each surpassed general anesthesia for patients undergoing endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, significantly reducing procedure time, and significantly reducing postoperative hospitalization, Dr. Rutger A. Stokmans said at the 2012 International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy.

All three anesthesia types linked with similar rates of both technical and clinical success of the aneurysm repairs. Regional anesthesia also led to a significantly lower rate of ICU admission, compared with both general and local anesthesia; local anesthesia showed no significant difference for this measure, compared with general anesthesia.

Based on these findings, local or regional anesthesia should be preferred for EVAR, and general anesthesia should usually be avoided, said Dr. Stokmans, a vascular surgeon at Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

These findings support the most recent anesthesia recommendations of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, which in 2011 guidelines for managing abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) cited local anesthesia as preferred for EVAR, with regional or general anesthesia reserved for patients with contraindications for local anesthesia, he said (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg .2011; 41[suppl. 1]:S1-S58). The most recent guidelines for AAA management from the Society for Vascular Surgery suggested using local or regional anesthesia over general anesthesia, he added (J. Vasc. Surg. 2009[suppl.];50:S2-S49).

But despite these recommendations, the most commonly used anesthesia type worldwide for EVAR repair of AAA has been general anesthesia, followed by regional anesthesia, with local treatment used least often, according to the registry data reported by Dr. Stokmans. Among the 1,199 patients enrolled in ENGAGE (Endurant Stent Graft Natural Selection Global Postmarketing Registry) during March 2009 to December 2010 in 30 countries on five continents, 749 (62%) underwent their EVAR with general anesthesia, 325 (27%) with regional, and 125 (10%) with local anesthesia. (Percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding.)

The registry data also showed striking regional variations in anesthesia use, with general anesthesia used on about 90% of patients in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and on about 70% of patients in Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom. But in Central Europe, regional anesthesia – used on nearly 70% of EVAR patients – dominated. The only region favoring local anesthesia was South America (Argentina, Columbia, and Uruguay), where about 50% of patients received local, but more than 40% received general anesthesia, he said. The registry contained no U.S. patients.

The average age of the EVAR patients was about 73 years. Those patients who underwent general anesthesia were significantly older, by an average of about 18 months, compared with those who received local or regional anesthesia.

The proportions of patients undergoing general, regional, or local anesthesia were similar in the subgroups of patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status scores of 1, 2, or 3. However, among the highest-risk patients included in the study – those with an ASA score of 4 – a significantly greater proportion of patients received general anesthesia. The multivariate models used in the analysis, therefore, were adjusted for age and for ASA score. About 42% of patients were in ASA class 2, and another 42% in class 3.

All patients were hemodynamically stable at the time of their enrollment. The maximum AAA diameter of registry patients was 6 cm, and about 88% of patients had an AAA diameter greater than 5 cm.

Average procedure times were 106 minutes in the general anesthesia patients, 95 minutes for regional, and 81 minutes for local – statistically significant differences among the three groups.

The average postoperative hospitalization was 5.2 days in the general anesthesia patients, 4.3 days in the regional patients, and 3.6 days in the local anesthesia patients, differences that were statistically significant among the groups.

The rate of technical surgical success was 98% in all three subgroups, and the rate of clinical success reached 97%-98% in all three groups. The rates of major adverse events during the 30 days following surgery were 5.1% in the general anesthesia patients, 3.2% in the local patients, and 2.2% in the regional anesthesia patients. None of these differences reached statistical significance. Major adverse events included death, MI, stroke, renal failure, blood loss greater than 1 L, and bowel ischemia. No patients developed paraplegia or respiratory failure.

Postoperative ICU admission occurred for 27% of the regional anesthesia patients, 35% of the general patients, and 42% of the local anesthesia patients. The rate among regional patients was significantly less than in the other two groups, but the difference in rates between the general and local anesthesia patients did not reach statistical significance.

The ENGAGE registry was organized and sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Endurant stent. Dr. Stokmans and his associates received an unrestricted research grant from Medtronic.

Old habits die hard. It can be hard to keep up with the rapid transformation of a procedure that was traditionally near the top of the magnitude food chain and is now usually much more innocuous. This slow adaptation probably affects not just vascular surgeons but also anesthesiologists.

Although the report by Stokmans et al did not include cases from the U.S., it is consistent with the paper published last year by Edwards et al (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1273-82) based on experience from the NSQIP database. Pulmonary morbidity and LOS were significantly lower after local compared to general anesthesia without a mortality difference.

Ultimately, the choice of anesthetic for EVAR should be a collaborative decision between the surgeon and anesthesiologist after considering each individual clinical situation. However, the wide regional variation in anesthetic technique reported by Stokmans suggests that style of practice, perhaps independent of the individual clinical circumstance, is also a major determinant. These conclusions are being drawn from cohorts where only 5%-10% of patients received local anesthesia so the possibility of selection bias remains high.

Nonetheless, based on these two studies, vascular surgeons (and anesthesiologists) should pause and give more thought to this issue before they automatically opt for general anesthesia for their EVAR patients. Since EVAR is all about reducing the perioperative morbidity of AAA repair, choice of anesthetic should also be more consciously considered.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and Chief of Vascular Surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Old habits die hard. It can be hard to keep up with the rapid transformation of a procedure that was traditionally near the top of the magnitude food chain and is now usually much more innocuous. This slow adaptation probably affects not just vascular surgeons but also anesthesiologists.

Although the report by Stokmans et al did not include cases from the U.S., it is consistent with the paper published last year by Edwards et al (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1273-82) based on experience from the NSQIP database. Pulmonary morbidity and LOS were significantly lower after local compared to general anesthesia without a mortality difference.

Ultimately, the choice of anesthetic for EVAR should be a collaborative decision between the surgeon and anesthesiologist after considering each individual clinical situation. However, the wide regional variation in anesthetic technique reported by Stokmans suggests that style of practice, perhaps independent of the individual clinical circumstance, is also a major determinant. These conclusions are being drawn from cohorts where only 5%-10% of patients received local anesthesia so the possibility of selection bias remains high.

Nonetheless, based on these two studies, vascular surgeons (and anesthesiologists) should pause and give more thought to this issue before they automatically opt for general anesthesia for their EVAR patients. Since EVAR is all about reducing the perioperative morbidity of AAA repair, choice of anesthetic should also be more consciously considered.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and Chief of Vascular Surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Old habits die hard. It can be hard to keep up with the rapid transformation of a procedure that was traditionally near the top of the magnitude food chain and is now usually much more innocuous. This slow adaptation probably affects not just vascular surgeons but also anesthesiologists.

Although the report by Stokmans et al did not include cases from the U.S., it is consistent with the paper published last year by Edwards et al (J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54:1273-82) based on experience from the NSQIP database. Pulmonary morbidity and LOS were significantly lower after local compared to general anesthesia without a mortality difference.

Ultimately, the choice of anesthetic for EVAR should be a collaborative decision between the surgeon and anesthesiologist after considering each individual clinical situation. However, the wide regional variation in anesthetic technique reported by Stokmans suggests that style of practice, perhaps independent of the individual clinical circumstance, is also a major determinant. These conclusions are being drawn from cohorts where only 5%-10% of patients received local anesthesia so the possibility of selection bias remains high.

Nonetheless, based on these two studies, vascular surgeons (and anesthesiologists) should pause and give more thought to this issue before they automatically opt for general anesthesia for their EVAR patients. Since EVAR is all about reducing the perioperative morbidity of AAA repair, choice of anesthetic should also be more consciously considered.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and Chief of Vascular Surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

MIAMI BEACH – Both local anesthesia and regional anesthesia each surpassed general anesthesia for patients undergoing endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, significantly reducing procedure time, and significantly reducing postoperative hospitalization, Dr. Rutger A. Stokmans said at the 2012 International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy.

All three anesthesia types linked with similar rates of both technical and clinical success of the aneurysm repairs. Regional anesthesia also led to a significantly lower rate of ICU admission, compared with both general and local anesthesia; local anesthesia showed no significant difference for this measure, compared with general anesthesia.

Based on these findings, local or regional anesthesia should be preferred for EVAR, and general anesthesia should usually be avoided, said Dr. Stokmans, a vascular surgeon at Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

These findings support the most recent anesthesia recommendations of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, which in 2011 guidelines for managing abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) cited local anesthesia as preferred for EVAR, with regional or general anesthesia reserved for patients with contraindications for local anesthesia, he said (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg .2011; 41[suppl. 1]:S1-S58). The most recent guidelines for AAA management from the Society for Vascular Surgery suggested using local or regional anesthesia over general anesthesia, he added (J. Vasc. Surg. 2009[suppl.];50:S2-S49).

But despite these recommendations, the most commonly used anesthesia type worldwide for EVAR repair of AAA has been general anesthesia, followed by regional anesthesia, with local treatment used least often, according to the registry data reported by Dr. Stokmans. Among the 1,199 patients enrolled in ENGAGE (Endurant Stent Graft Natural Selection Global Postmarketing Registry) during March 2009 to December 2010 in 30 countries on five continents, 749 (62%) underwent their EVAR with general anesthesia, 325 (27%) with regional, and 125 (10%) with local anesthesia. (Percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding.)

The registry data also showed striking regional variations in anesthesia use, with general anesthesia used on about 90% of patients in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and on about 70% of patients in Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom. But in Central Europe, regional anesthesia – used on nearly 70% of EVAR patients – dominated. The only region favoring local anesthesia was South America (Argentina, Columbia, and Uruguay), where about 50% of patients received local, but more than 40% received general anesthesia, he said. The registry contained no U.S. patients.

The average age of the EVAR patients was about 73 years. Those patients who underwent general anesthesia were significantly older, by an average of about 18 months, compared with those who received local or regional anesthesia.

The proportions of patients undergoing general, regional, or local anesthesia were similar in the subgroups of patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status scores of 1, 2, or 3. However, among the highest-risk patients included in the study – those with an ASA score of 4 – a significantly greater proportion of patients received general anesthesia. The multivariate models used in the analysis, therefore, were adjusted for age and for ASA score. About 42% of patients were in ASA class 2, and another 42% in class 3.

All patients were hemodynamically stable at the time of their enrollment. The maximum AAA diameter of registry patients was 6 cm, and about 88% of patients had an AAA diameter greater than 5 cm.

Average procedure times were 106 minutes in the general anesthesia patients, 95 minutes for regional, and 81 minutes for local – statistically significant differences among the three groups.

The average postoperative hospitalization was 5.2 days in the general anesthesia patients, 4.3 days in the regional patients, and 3.6 days in the local anesthesia patients, differences that were statistically significant among the groups.

The rate of technical surgical success was 98% in all three subgroups, and the rate of clinical success reached 97%-98% in all three groups. The rates of major adverse events during the 30 days following surgery were 5.1% in the general anesthesia patients, 3.2% in the local patients, and 2.2% in the regional anesthesia patients. None of these differences reached statistical significance. Major adverse events included death, MI, stroke, renal failure, blood loss greater than 1 L, and bowel ischemia. No patients developed paraplegia or respiratory failure.

Postoperative ICU admission occurred for 27% of the regional anesthesia patients, 35% of the general patients, and 42% of the local anesthesia patients. The rate among regional patients was significantly less than in the other two groups, but the difference in rates between the general and local anesthesia patients did not reach statistical significance.

The ENGAGE registry was organized and sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Endurant stent. Dr. Stokmans and his associates received an unrestricted research grant from Medtronic.

MIAMI BEACH – Both local anesthesia and regional anesthesia each surpassed general anesthesia for patients undergoing endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, significantly reducing procedure time, and significantly reducing postoperative hospitalization, Dr. Rutger A. Stokmans said at the 2012 International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy.

All three anesthesia types linked with similar rates of both technical and clinical success of the aneurysm repairs. Regional anesthesia also led to a significantly lower rate of ICU admission, compared with both general and local anesthesia; local anesthesia showed no significant difference for this measure, compared with general anesthesia.

Based on these findings, local or regional anesthesia should be preferred for EVAR, and general anesthesia should usually be avoided, said Dr. Stokmans, a vascular surgeon at Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

These findings support the most recent anesthesia recommendations of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, which in 2011 guidelines for managing abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) cited local anesthesia as preferred for EVAR, with regional or general anesthesia reserved for patients with contraindications for local anesthesia, he said (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg .2011; 41[suppl. 1]:S1-S58). The most recent guidelines for AAA management from the Society for Vascular Surgery suggested using local or regional anesthesia over general anesthesia, he added (J. Vasc. Surg. 2009[suppl.];50:S2-S49).

But despite these recommendations, the most commonly used anesthesia type worldwide for EVAR repair of AAA has been general anesthesia, followed by regional anesthesia, with local treatment used least often, according to the registry data reported by Dr. Stokmans. Among the 1,199 patients enrolled in ENGAGE (Endurant Stent Graft Natural Selection Global Postmarketing Registry) during March 2009 to December 2010 in 30 countries on five continents, 749 (62%) underwent their EVAR with general anesthesia, 325 (27%) with regional, and 125 (10%) with local anesthesia. (Percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding.)

The registry data also showed striking regional variations in anesthesia use, with general anesthesia used on about 90% of patients in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and on about 70% of patients in Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom. But in Central Europe, regional anesthesia – used on nearly 70% of EVAR patients – dominated. The only region favoring local anesthesia was South America (Argentina, Columbia, and Uruguay), where about 50% of patients received local, but more than 40% received general anesthesia, he said. The registry contained no U.S. patients.

The average age of the EVAR patients was about 73 years. Those patients who underwent general anesthesia were significantly older, by an average of about 18 months, compared with those who received local or regional anesthesia.

The proportions of patients undergoing general, regional, or local anesthesia were similar in the subgroups of patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status scores of 1, 2, or 3. However, among the highest-risk patients included in the study – those with an ASA score of 4 – a significantly greater proportion of patients received general anesthesia. The multivariate models used in the analysis, therefore, were adjusted for age and for ASA score. About 42% of patients were in ASA class 2, and another 42% in class 3.

All patients were hemodynamically stable at the time of their enrollment. The maximum AAA diameter of registry patients was 6 cm, and about 88% of patients had an AAA diameter greater than 5 cm.

Average procedure times were 106 minutes in the general anesthesia patients, 95 minutes for regional, and 81 minutes for local – statistically significant differences among the three groups.

The average postoperative hospitalization was 5.2 days in the general anesthesia patients, 4.3 days in the regional patients, and 3.6 days in the local anesthesia patients, differences that were statistically significant among the groups.

The rate of technical surgical success was 98% in all three subgroups, and the rate of clinical success reached 97%-98% in all three groups. The rates of major adverse events during the 30 days following surgery were 5.1% in the general anesthesia patients, 3.2% in the local patients, and 2.2% in the regional anesthesia patients. None of these differences reached statistical significance. Major adverse events included death, MI, stroke, renal failure, blood loss greater than 1 L, and bowel ischemia. No patients developed paraplegia or respiratory failure.

Postoperative ICU admission occurred for 27% of the regional anesthesia patients, 35% of the general patients, and 42% of the local anesthesia patients. The rate among regional patients was significantly less than in the other two groups, but the difference in rates between the general and local anesthesia patients did not reach statistical significance.

The ENGAGE registry was organized and sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Endurant stent. Dr. Stokmans and his associates received an unrestricted research grant from Medtronic.

Major Finding: Postoperative hospitalization averaged 5.2 days in EVAR patients treated with general anesthesia, 4.3 days with regional anesthesia, and 3.6 days with local anesthesia.

Data Source: ENGAGE, an international registry of 1,199 patients who underwent EVAR for an abdominal aortic aneurysm during 2009 or 2010.

Disclosures: The ENGAGE registry was organized and sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Endurant EVAR stent. Dr. Stokmans and his associates received an unrestricted research grant from Medtronic. Dr. Stokmans said that he had no other disclosures.

Incidental Findings Common on Post-EVAR Serial CT Scans

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. (EGMN) – Serial computed tomography scans commonly used to monitor patients following endovascular aneurysm repair may be unnecessary after 6 years, according to the findings of a retrospective study of 2,965 scans in 608 EVAR patients.

Furthermore, such scans are more likely to detect a clinically significant incidental finding that warrants further workup than to find a problem with the endograft, Dr. Elizabeth L. Detschelt said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery .

The average annual rate of detection of EVAR-related findings was 4% (range 2%-5%), which remained constant over the first 6 years of follow-up, and the rate after 6 years was 0%. However, the annual detection rate for new clinically significant incidental findings on these scans was 25% (range 14%-32%), which remained constant for more than 10 years, said Dr. Detschelt of Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh.

On multivariate analysis, predictors of detection of new clinically significant findings included age over 65 years, glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and tobacco use. No predictors were identified for EVAR-related findings, she noted.

The patients underwent EVAR for infrarenal aneurysm at a single institution between Dec. 1, 1999, and Nov. 30, 2009, and were followed for a mean of 32 months. These results are particularly relevant, Dr. Detschelt said, because risks from repeated scans, which are commonly used for serial imaging in EVAR patients to monitor for endoleak and other problems, are currently a topic of intense debate.

"Recently, the literature has really been inundated with concerns about the cumulative effects of such radiation exposure by these CT scan protocols, and in addition there’s a fair amount of literature to cite a very high rate of incidental findings that we detect on this follow-up with CT protocol," said Dr. Detschelt. Although such findings require follow-up, the literature suggests that this often falls through the cracks, she added.

In this study, EVAR-related findings included endoleak, limb occlusion, and endograft migration. Clinically significant incidental findings were varied, with the most common occurring in the broad categories of genitourinary findings, hepatobiliary findings, hernias, pulmonary neoplasms, and other vascular and cardiac lesions.

Not only do the findings suggest that serial imaging is not needed for EVAR-related concerns after 6 years, but they also underscore the importance of carefully evaluating post-EVAR CT scans for clinically significant incidental findings.

"As the ordering physicians of these CT scans, it is our legal responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate workup, so this is going to mean that not only do we have to look at the scans to assess the status of our aneurysm repair, but we also have to read the radiologist’s report to make sure we’re not missing something," she said.

That’s particularly true for patients who are older, who smoke, and who have a degree of renal insufficiency, she added.

The findings also raise the question of whether post-EVAR patients should undergo monitoring using other imaging techniques such as ultrasound, or whether a less frequent CT scan protocol can be used to reduce patient exposure to radiation and reduce patient costs.

These questions – along with the bigger question of whether it is more prudent to not use CT scans in order to reduce radiation exposure or to continue with CT monitoring to pick up findings that potentially could save or improve lives – require better data to inform decision making, she concluded.

During a discussion period after Dr. Detschelt’s talk, one audience member cautioned against suggesting that CT monitoring be considered for the purpose of detecting incidental nonvascular issues, saying that raises the argument of whether the general population aged 65-75 years should also undergo serial CT scans to find incidental nonvascular issues. He also noted that at his institution, the concerns about serial CT monitoring post EVAR are addressed in part by using duplex ultrasound in the immediate postoperative period, with follow-up by duplex ultrasound in those patients with no problems detected on the initial ultrasound.

He said findings from his experience and others have been published, and show that this is approach is "probably safe and effective." Dr. Detschelt responded that while duplex ultrasound is not used immediately postoperatively at her institution, there has been a move toward using it for long-term follow-up there. At many institutions, however, workforce issues come into play, because the duplex studies are more time intensive and require specially trained vascular staff, she said.

Dr. Detschelt had no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. (EGMN) – Serial computed tomography scans commonly used to monitor patients following endovascular aneurysm repair may be unnecessary after 6 years, according to the findings of a retrospective study of 2,965 scans in 608 EVAR patients.

Furthermore, such scans are more likely to detect a clinically significant incidental finding that warrants further workup than to find a problem with the endograft, Dr. Elizabeth L. Detschelt said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery .

The average annual rate of detection of EVAR-related findings was 4% (range 2%-5%), which remained constant over the first 6 years of follow-up, and the rate after 6 years was 0%. However, the annual detection rate for new clinically significant incidental findings on these scans was 25% (range 14%-32%), which remained constant for more than 10 years, said Dr. Detschelt of Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh.

On multivariate analysis, predictors of detection of new clinically significant findings included age over 65 years, glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and tobacco use. No predictors were identified for EVAR-related findings, she noted.

The patients underwent EVAR for infrarenal aneurysm at a single institution between Dec. 1, 1999, and Nov. 30, 2009, and were followed for a mean of 32 months. These results are particularly relevant, Dr. Detschelt said, because risks from repeated scans, which are commonly used for serial imaging in EVAR patients to monitor for endoleak and other problems, are currently a topic of intense debate.

"Recently, the literature has really been inundated with concerns about the cumulative effects of such radiation exposure by these CT scan protocols, and in addition there’s a fair amount of literature to cite a very high rate of incidental findings that we detect on this follow-up with CT protocol," said Dr. Detschelt. Although such findings require follow-up, the literature suggests that this often falls through the cracks, she added.

In this study, EVAR-related findings included endoleak, limb occlusion, and endograft migration. Clinically significant incidental findings were varied, with the most common occurring in the broad categories of genitourinary findings, hepatobiliary findings, hernias, pulmonary neoplasms, and other vascular and cardiac lesions.

Not only do the findings suggest that serial imaging is not needed for EVAR-related concerns after 6 years, but they also underscore the importance of carefully evaluating post-EVAR CT scans for clinically significant incidental findings.

"As the ordering physicians of these CT scans, it is our legal responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate workup, so this is going to mean that not only do we have to look at the scans to assess the status of our aneurysm repair, but we also have to read the radiologist’s report to make sure we’re not missing something," she said.

That’s particularly true for patients who are older, who smoke, and who have a degree of renal insufficiency, she added.

The findings also raise the question of whether post-EVAR patients should undergo monitoring using other imaging techniques such as ultrasound, or whether a less frequent CT scan protocol can be used to reduce patient exposure to radiation and reduce patient costs.

These questions – along with the bigger question of whether it is more prudent to not use CT scans in order to reduce radiation exposure or to continue with CT monitoring to pick up findings that potentially could save or improve lives – require better data to inform decision making, she concluded.

During a discussion period after Dr. Detschelt’s talk, one audience member cautioned against suggesting that CT monitoring be considered for the purpose of detecting incidental nonvascular issues, saying that raises the argument of whether the general population aged 65-75 years should also undergo serial CT scans to find incidental nonvascular issues. He also noted that at his institution, the concerns about serial CT monitoring post EVAR are addressed in part by using duplex ultrasound in the immediate postoperative period, with follow-up by duplex ultrasound in those patients with no problems detected on the initial ultrasound.

He said findings from his experience and others have been published, and show that this is approach is "probably safe and effective." Dr. Detschelt responded that while duplex ultrasound is not used immediately postoperatively at her institution, there has been a move toward using it for long-term follow-up there. At many institutions, however, workforce issues come into play, because the duplex studies are more time intensive and require specially trained vascular staff, she said.

Dr. Detschelt had no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. (EGMN) – Serial computed tomography scans commonly used to monitor patients following endovascular aneurysm repair may be unnecessary after 6 years, according to the findings of a retrospective study of 2,965 scans in 608 EVAR patients.

Furthermore, such scans are more likely to detect a clinically significant incidental finding that warrants further workup than to find a problem with the endograft, Dr. Elizabeth L. Detschelt said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery .

The average annual rate of detection of EVAR-related findings was 4% (range 2%-5%), which remained constant over the first 6 years of follow-up, and the rate after 6 years was 0%. However, the annual detection rate for new clinically significant incidental findings on these scans was 25% (range 14%-32%), which remained constant for more than 10 years, said Dr. Detschelt of Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh.

On multivariate analysis, predictors of detection of new clinically significant findings included age over 65 years, glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and tobacco use. No predictors were identified for EVAR-related findings, she noted.

The patients underwent EVAR for infrarenal aneurysm at a single institution between Dec. 1, 1999, and Nov. 30, 2009, and were followed for a mean of 32 months. These results are particularly relevant, Dr. Detschelt said, because risks from repeated scans, which are commonly used for serial imaging in EVAR patients to monitor for endoleak and other problems, are currently a topic of intense debate.

"Recently, the literature has really been inundated with concerns about the cumulative effects of such radiation exposure by these CT scan protocols, and in addition there’s a fair amount of literature to cite a very high rate of incidental findings that we detect on this follow-up with CT protocol," said Dr. Detschelt. Although such findings require follow-up, the literature suggests that this often falls through the cracks, she added.

In this study, EVAR-related findings included endoleak, limb occlusion, and endograft migration. Clinically significant incidental findings were varied, with the most common occurring in the broad categories of genitourinary findings, hepatobiliary findings, hernias, pulmonary neoplasms, and other vascular and cardiac lesions.

Not only do the findings suggest that serial imaging is not needed for EVAR-related concerns after 6 years, but they also underscore the importance of carefully evaluating post-EVAR CT scans for clinically significant incidental findings.

"As the ordering physicians of these CT scans, it is our legal responsibility to ensure that they have appropriate workup, so this is going to mean that not only do we have to look at the scans to assess the status of our aneurysm repair, but we also have to read the radiologist’s report to make sure we’re not missing something," she said.

That’s particularly true for patients who are older, who smoke, and who have a degree of renal insufficiency, she added.

The findings also raise the question of whether post-EVAR patients should undergo monitoring using other imaging techniques such as ultrasound, or whether a less frequent CT scan protocol can be used to reduce patient exposure to radiation and reduce patient costs.

These questions – along with the bigger question of whether it is more prudent to not use CT scans in order to reduce radiation exposure or to continue with CT monitoring to pick up findings that potentially could save or improve lives – require better data to inform decision making, she concluded.