User login

High-dose donepezil or memantine: Next step for Alzheimer’s disease?

Although cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and memantine at standard doses may slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as assessed by cognitive, functional, and global measures, this effect is relatively modest. For the estimated 5.4 million Americans with AD1—more than one-half of whom have moderate to severe disease2—there is a great need for new approaches to slow AD progression.

High doses of donepezil or memantine may be the next step in achieving better results than standard pharmacologic treatments for AD. This article presents the possible benefits and indications for high doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) for managing moderate to severe AD and their safety and tolerability profiles.

Current treatments offer modest benefits

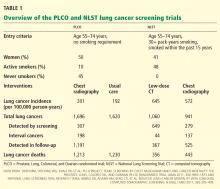

AD treatments comprise 2 categories: ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine (Table 1).3,4 All ChEIs are FDA-approved for mild to moderate AD; donepezil also is approved for severe AD. Memantine is approved for moderate to severe AD, either alone or in combination with ChEIs. Until recently, the maximum FDA-approved doses were donepezil, 10 mg/d, and memantine, 20 mg/d. However, these dosages are associated with only modest beneficial effects in managing cognitive deterioration in patients with moderate to severe dementia.5,6 Studies have reported that combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, and memantine is well tolerated and may result in synergistic benefits by affecting different neurotransmitters in patients with moderate to severe AD.7,8

Recently, the FDA approved higher daily doses of donepezil (23 mg) and memantine (28 mg) for moderate to severe AD on the basis of positive phase III trial results.9-11 Donepezil, 23 mg/d, currently is marketed in the United States; the availability date for memantine, 28 mg/d, was undetermined at press time.

Table 1

FDA-approved treatments for Alzheimer’s disease

| Drug | Maximum daily dose | Mechanism of action | Indication | Common side effects/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrine | 160 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea. First ChEI to be approved, but rarely used because of associated possible hepatotoxicity |

| Donepezil | 10 mg/d | ChEI | All stages of AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sleep disturbance |

| Rivastigmine | 12 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Galantamine | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Memantine | 20 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| Galantamine ER | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Rivastigmine transdermal system | 9.5 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Donepezil 23 | 23 mg/d | ChEI | Moderate to severe AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Memantine ER | 28 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ChEI: cholinesterase inhibitor; ER: extended release; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate Source: References 3,4 | ||||

High-dose donepezil (23 mg/d)

Cognitive decline with AD has been associated with increasing loss of cholinergic neurons and cholinergic activities, particularly in areas associated with memory/cognition and learning, including cortical areas involving the temporal lobe, hippocampus, and nucleus basalis of Meynert.12-14 In addition, evidence suggests that increasing levels of acetylcholine by using ChEIs can enhance cognitive function.13,15

Donepezil is a selective, reversible ChEI believed to enhance central cholinergic function.15 Randomized clinical trials assessing dose-response with donepezil, 5 mg/d and 10 mg/d, have demonstrated more benefit in cognition with either dose than placebo. The 10 mg/d dose was more effective than 5 mg/d in patients with mild to moderate and severe AD.16-18 In patients with advanced AD who are stable on 5 mg/d, increasing to 10 mg/d could slow the progression of cognitive decline.18

Rationale for higher doses. Positron emission tomography studies have shown that at stable doses of donepezil, 5 mg/d or 10 mg/d, average cortical acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition was <30%.19,20 Based on these findings, researchers thought that cortical AChE inhibition may be suboptimal with donepezil, 10 mg/d, and that higher doses of ChEI may be required in patients with more advanced AD—and therefore more cholinergic loss—for adequate cholinesterase inhibition. In a pilot study of patients with mild to moderate AD, higher doses of donepezil (15 mg/d and 20 mg/d) were reported to be safe and well tolerated.21

The 23-mg/d donepezil formulation was developed to provide a higher dose administered once daily without a sharp rise in peak concentration. The FDA approved donepezil, 23 mg/d, for patients with moderate to severe AD on the basis of phase III trial results.9,22 In a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, head-to-head clinical trial, >1,400 patients with moderate to severe AD (Mini-Mental State Exam [MMSE]: 0 to 20) on a stable dose of donepezil, 10 mg/d, for ≥3 months were randomly assigned to receive high-dose donepezil (23 mg/d) or standard-dose donepezil (10 mg/d) for 24 weeks.9,22 Patients in the 23-mg/d group showed a statistically significant improvement in cognition compared with the 10-mg/d group. The difference between groups on a measure of global improvement was not significant.9,22 However, in a post-hoc analysis, it was demonstrated that a subgroup of patients with more severe cognitive impairment (baseline MMSE: 0 to 16), showed significant improvement in cognition as well as global functioning.9

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during the study were higher in patients receiving 23 mg/d (74%) than those receiving 10 mg/d (64%). The most common TEAEs in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups were nausea (12% vs 3%, respectively), vomiting (9% vs 3%), and diarrhea (8% vs 5%) (Table 2).22 These gastrointestinal adverse effects were more frequent during the first month of treatment and were relatively infrequent beyond 1 month. Serious TEAEs, such as falls, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, syncope, aggression, and confusional state, were noted in a similar proportion of patients in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups; most of these were considered unrelated to treatment. No drug-related deaths occurred during the study. High-dose (23 mg/d) donepezil generally was well tolerated, with a typical ChEI safety profile but superior efficacy.

A recent commentary discussed the issue of effect size and whether a 2.2-point difference on a 100-point scale (the Severe Impairment Battery [SIB]) is clinically meaningful.23 As with all anti-dementia therapies, in any cohort some patients will gain considerably more than 2.2 points on the SIB, which is clinically significant. A 6-month trial is recommended to identify these optimal responders.

Table 2

High-dose vs standard-dose donepezil: Treatment-emergent adverse events

| Adverse event | Donepezil, 23 mg/d | Donepezil,10 mg/d |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 12% | 3% |

| Vomiting | 9% | 3% |

| Diarrhea | 8% | 5% |

| Anorexia | 5% | 2% |

| Dizziness | 5% | 3% |

| Weight decrease | 5% | 3% |

| Headache | 4% | 3% |

| Insomnia | 3% | 2% |

| Urinary incontinence | 3% | 1% |

| Fatigue | 2% | 1% |

| Weakness | 2% | 1% |

| Somnolence | 2% | 1% |

| Contusion | 2% | 0% |

| Source: Reference 22 | ||

High-dose memantine

Memantine is an NMDA receptor antagonist, which works on glutamate, an ubiquitous neurotransmitter in the brain that serves many functions. For reasons that are not fully understood, in AD glutamate becomes excitotoxic and causes neuronal death.

Some researchers have hypothesized that if safe and well tolerated, a memantine dose >20 mg/d may have better efficacy than a lower dose. Memantine’s manufacturer has developed an extended-release (ER), once-daily formulation of memantine, 28 mg/d, to improve adherence and possibly increase efficacy.10,11 Because of memantine ER’s relatively slow absorption rate and longer median Tmax, of 12 hours, there is minimal fluctuation in plasma levels during steady-state dosing intervals compared with the immediate-release (IR) formulation.10

In a phase I study of 24 healthy volunteers that investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, TEAEs were mild; the most common were headache, somnolence, and dizziness.10 During memantine treatment, there were no serious adverse events, potential significant changes in patients’ vital signs, or deaths.

Memantine ER plus ChEI. A multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind study compared memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and placebo in patients with moderate to severe AD (MMSE: 3 to 14).11 All patients were receiving concurrent, stable ChEI treatment (donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine) for ≥3 months before the study. Patients treated with memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and ChEI (n = 342) showed a significant improvement compared with the placebo/ChEI group (n = 335) in cognition and global functioning. Patients receiving memantine/ChEI also showed statistically significant benefits on behavior and verbal fluency testing compared with patients receiving placebo/ChEI. Memantine was well tolerated; most adverse events were mild or moderate. The most common adverse events in the memantine/ChEI group that occurred at a higher rate relative to the placebo/ChEI group were headache (5.6% vs 5.1%, respectively), diarrhea (5.0% vs 3.9%), and dizziness (4.7% vs 1.5%). There were no deaths related to memantine (Table 3).11

Memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may be tolerated better than the IR formulation because of less plasma level fluctuation during the steady-state dosing interval. Also, memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may offer better efficacy over memantine IR, 20 mg/d, because of dose-dependent cognitive, global, and behavioral effects. In addition, once-daily dosing of memantine ER may improve adherence compared with the IR formulation.24

In patients with severe renal impairment, dosage of memantine IR should be reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d.25 However, there is no available information regarding the dosing, safety, and tolerability of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, in patients with renal disease.

Table3

High-dose memantine: Treatment-emergent adverse eventsa

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 335) | Memantine ER (n = 341) |

|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 214 (63.9%) | 214 (62.8%) |

| Fall | 26 (7.8%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (7.2%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Headache | 17 (5.1%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (3.9%) | 17 (5.0%) |

| Dizziness | 5 (1.5%) | 16 (4.7%) |

| Influenza | 9 (2.7%) | 15 (4.4%) |

| Insomnia | 16 (4.8%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Agitation | 15 (4.5%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Hypertension | 8 (2.4%) | 13 (3.8%) |

| Anxiety | 9 (2.7%) | 12 (3.5%) |

| Depression | 5 (1.5%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Weight increased | 3 (0.9%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Constipation | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Somnolence | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Back pain | 2 (0.6%) | 9 (2.6%) |

| Aggression | 5 (1.5%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Hypotension | 5 (1.5%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Vomiting | 4 (1.2%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (0.6%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 10 (3.0%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Confusional state | 7 (2.1%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Weight decreased | 11 (3.3%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Nausea | 7 (2.1%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Irritability | 8 (2.4%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| Cough | 8 (2.4%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| aData [n (%)] include all adverse events experienced by ≥2% patients in either group (safety population). Adverse events that were experienced at twice the rate in 1 group compared with the other are indicated by bold type ER: extended-release (28 mg); TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event Source: Reference 11 | ||

Recommendations

Because there are few FDA-approved treatments for AD, higher doses of donepezil or memantine may be an option for patients who have “maxed out” on their AD therapy or no longer respond to lower doses. Higher doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) could improve medication adherence because both are once-daily preparations. In clinical trials, donepezil, 23 mg/d, was more effective than donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Whether memantine ER, 28 mg/d, is superior to memantine IR, 20 mg/d, needs to be investigated in head-to-head, double-blind, controlled studies.

For patients with moderate to severe AD, donepezil, 23 mg, is associated with greater benefits in cognition compared with donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Similarly, because of potentially superior efficacy because of a higher dose, memantine ER, 28 mg, might best help patients with moderate to severe AD, specifically those who either don’t respond or lose response to memantine IR, 20 mg/d. Combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, with memantine is associated with slower cognitive decline and short and long-term benefits on measures of cognition, activities of daily living, global outcome, and behavior.7,26 However, additional clinical trials are needed to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of combination therapy with higher doses of donepezil and memantine ER.

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers.

- Lleó A, Greenberg SM, Growdon JH. Current pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:513-533.

Drug Brand Names

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Galantamine • Razadyne

- Memantine • Namenda

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Tacrine • Cognex

Disclosures

Dr. Grossberg’s academic department has received research funding from Forest Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer Inc. Dr. Grossberg has received grant/research support from Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, and Pfizer, Inc.; is a consultant to Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Otsuka; and is on the Safety Monitoring Committee for Merck.

Dr. Singh reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alzheimer’s Association, Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(2):208-244.

2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119-1122.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. Alzheimer’s disease medications. http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-disease-medications-fact-sheet. Accessed May 10 2012.

4. Osborn GG, Saunders AV. Current treatments for patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(9 suppl 8):S16-S26.

5. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379-397.

6. Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):56-67.

7. Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(3):317-324.

8. Xiong G, Doraiswamy PM. Combination drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: what is evidence-based and what is not? Geriatrics. 2005;60(6):22-26.

9. Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of high (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1234-1251.

10. Periclou A, Hu Y. Extended-release memantine capsule (28 mg once daily): a multiple dose, open-label study evaluating steady-state pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

11. Grossberg GT, Manes F, Allegri R, et al. A multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial of memantine extended-release capsule (28 mg, once daily) in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

12. Geula C, Mesulam MM. Systematic regional variations in the loss of cortical cholinergic fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6(2):165-177.

13. Whitehouse PJ. The cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 13):19-22.

14. Teipel SJ, Flatz WH, Heinsen H, et al. Measurement of basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. Brain. 2005;128(11):2626-2644.

15. Shintani EY, Uchida KM. Donepezil: an anticholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(24):2805-2810.

16. Homma A, Imai Y, Tago H, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease in a Japanese population: results from a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(5):399-407.

17. Whitehead A, Perdomo C, Pratt RD, et al. Donepezil for the symptomatic treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):624-633.

18. Nozawa M, Ichimiya Y, Nozawa E, et al. Clinical effects of high oral dose of donepezil for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):50-55.

19. Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Frey KA, et al. Limited donepezil inhibition of acetylcholinesterase measured with positron emission tomography in living Alzheimer cerebral cortex. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(3):391-395.

20. Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, et al. Degree of inhibition of cortical acetylcholinesterase activity and cognitive effects by donepezil treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(3):315-319.

21. Doody RS, Corey-Bloom J, Zhang R, et al. Safety and tolerability of donepezil at doses up to 20 mg/day: results from a pilot study in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(2):163-174.

22. Aricept [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake NJ: Eisai Co.; 2012.

23. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. How the FDA forgot the evidence: the case of donepezil 23 mg. BMJ. 2012;344:e1086.-doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1086.

24. Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):e22-e33.

25. Periclou A, Ventura D, Rao N, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of memantine in healthy and renally impaired subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(1):134-143.

26. Atri A, Shaughnessy LW, Locascio JJ, et al. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(3):209-221.

Although cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and memantine at standard doses may slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as assessed by cognitive, functional, and global measures, this effect is relatively modest. For the estimated 5.4 million Americans with AD1—more than one-half of whom have moderate to severe disease2—there is a great need for new approaches to slow AD progression.

High doses of donepezil or memantine may be the next step in achieving better results than standard pharmacologic treatments for AD. This article presents the possible benefits and indications for high doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) for managing moderate to severe AD and their safety and tolerability profiles.

Current treatments offer modest benefits

AD treatments comprise 2 categories: ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine (Table 1).3,4 All ChEIs are FDA-approved for mild to moderate AD; donepezil also is approved for severe AD. Memantine is approved for moderate to severe AD, either alone or in combination with ChEIs. Until recently, the maximum FDA-approved doses were donepezil, 10 mg/d, and memantine, 20 mg/d. However, these dosages are associated with only modest beneficial effects in managing cognitive deterioration in patients with moderate to severe dementia.5,6 Studies have reported that combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, and memantine is well tolerated and may result in synergistic benefits by affecting different neurotransmitters in patients with moderate to severe AD.7,8

Recently, the FDA approved higher daily doses of donepezil (23 mg) and memantine (28 mg) for moderate to severe AD on the basis of positive phase III trial results.9-11 Donepezil, 23 mg/d, currently is marketed in the United States; the availability date for memantine, 28 mg/d, was undetermined at press time.

Table 1

FDA-approved treatments for Alzheimer’s disease

| Drug | Maximum daily dose | Mechanism of action | Indication | Common side effects/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrine | 160 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea. First ChEI to be approved, but rarely used because of associated possible hepatotoxicity |

| Donepezil | 10 mg/d | ChEI | All stages of AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sleep disturbance |

| Rivastigmine | 12 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Galantamine | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Memantine | 20 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| Galantamine ER | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Rivastigmine transdermal system | 9.5 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Donepezil 23 | 23 mg/d | ChEI | Moderate to severe AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Memantine ER | 28 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ChEI: cholinesterase inhibitor; ER: extended release; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate Source: References 3,4 | ||||

High-dose donepezil (23 mg/d)

Cognitive decline with AD has been associated with increasing loss of cholinergic neurons and cholinergic activities, particularly in areas associated with memory/cognition and learning, including cortical areas involving the temporal lobe, hippocampus, and nucleus basalis of Meynert.12-14 In addition, evidence suggests that increasing levels of acetylcholine by using ChEIs can enhance cognitive function.13,15

Donepezil is a selective, reversible ChEI believed to enhance central cholinergic function.15 Randomized clinical trials assessing dose-response with donepezil, 5 mg/d and 10 mg/d, have demonstrated more benefit in cognition with either dose than placebo. The 10 mg/d dose was more effective than 5 mg/d in patients with mild to moderate and severe AD.16-18 In patients with advanced AD who are stable on 5 mg/d, increasing to 10 mg/d could slow the progression of cognitive decline.18

Rationale for higher doses. Positron emission tomography studies have shown that at stable doses of donepezil, 5 mg/d or 10 mg/d, average cortical acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition was <30%.19,20 Based on these findings, researchers thought that cortical AChE inhibition may be suboptimal with donepezil, 10 mg/d, and that higher doses of ChEI may be required in patients with more advanced AD—and therefore more cholinergic loss—for adequate cholinesterase inhibition. In a pilot study of patients with mild to moderate AD, higher doses of donepezil (15 mg/d and 20 mg/d) were reported to be safe and well tolerated.21

The 23-mg/d donepezil formulation was developed to provide a higher dose administered once daily without a sharp rise in peak concentration. The FDA approved donepezil, 23 mg/d, for patients with moderate to severe AD on the basis of phase III trial results.9,22 In a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, head-to-head clinical trial, >1,400 patients with moderate to severe AD (Mini-Mental State Exam [MMSE]: 0 to 20) on a stable dose of donepezil, 10 mg/d, for ≥3 months were randomly assigned to receive high-dose donepezil (23 mg/d) or standard-dose donepezil (10 mg/d) for 24 weeks.9,22 Patients in the 23-mg/d group showed a statistically significant improvement in cognition compared with the 10-mg/d group. The difference between groups on a measure of global improvement was not significant.9,22 However, in a post-hoc analysis, it was demonstrated that a subgroup of patients with more severe cognitive impairment (baseline MMSE: 0 to 16), showed significant improvement in cognition as well as global functioning.9

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during the study were higher in patients receiving 23 mg/d (74%) than those receiving 10 mg/d (64%). The most common TEAEs in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups were nausea (12% vs 3%, respectively), vomiting (9% vs 3%), and diarrhea (8% vs 5%) (Table 2).22 These gastrointestinal adverse effects were more frequent during the first month of treatment and were relatively infrequent beyond 1 month. Serious TEAEs, such as falls, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, syncope, aggression, and confusional state, were noted in a similar proportion of patients in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups; most of these were considered unrelated to treatment. No drug-related deaths occurred during the study. High-dose (23 mg/d) donepezil generally was well tolerated, with a typical ChEI safety profile but superior efficacy.

A recent commentary discussed the issue of effect size and whether a 2.2-point difference on a 100-point scale (the Severe Impairment Battery [SIB]) is clinically meaningful.23 As with all anti-dementia therapies, in any cohort some patients will gain considerably more than 2.2 points on the SIB, which is clinically significant. A 6-month trial is recommended to identify these optimal responders.

Table 2

High-dose vs standard-dose donepezil: Treatment-emergent adverse events

| Adverse event | Donepezil, 23 mg/d | Donepezil,10 mg/d |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 12% | 3% |

| Vomiting | 9% | 3% |

| Diarrhea | 8% | 5% |

| Anorexia | 5% | 2% |

| Dizziness | 5% | 3% |

| Weight decrease | 5% | 3% |

| Headache | 4% | 3% |

| Insomnia | 3% | 2% |

| Urinary incontinence | 3% | 1% |

| Fatigue | 2% | 1% |

| Weakness | 2% | 1% |

| Somnolence | 2% | 1% |

| Contusion | 2% | 0% |

| Source: Reference 22 | ||

High-dose memantine

Memantine is an NMDA receptor antagonist, which works on glutamate, an ubiquitous neurotransmitter in the brain that serves many functions. For reasons that are not fully understood, in AD glutamate becomes excitotoxic and causes neuronal death.

Some researchers have hypothesized that if safe and well tolerated, a memantine dose >20 mg/d may have better efficacy than a lower dose. Memantine’s manufacturer has developed an extended-release (ER), once-daily formulation of memantine, 28 mg/d, to improve adherence and possibly increase efficacy.10,11 Because of memantine ER’s relatively slow absorption rate and longer median Tmax, of 12 hours, there is minimal fluctuation in plasma levels during steady-state dosing intervals compared with the immediate-release (IR) formulation.10

In a phase I study of 24 healthy volunteers that investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, TEAEs were mild; the most common were headache, somnolence, and dizziness.10 During memantine treatment, there were no serious adverse events, potential significant changes in patients’ vital signs, or deaths.

Memantine ER plus ChEI. A multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind study compared memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and placebo in patients with moderate to severe AD (MMSE: 3 to 14).11 All patients were receiving concurrent, stable ChEI treatment (donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine) for ≥3 months before the study. Patients treated with memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and ChEI (n = 342) showed a significant improvement compared with the placebo/ChEI group (n = 335) in cognition and global functioning. Patients receiving memantine/ChEI also showed statistically significant benefits on behavior and verbal fluency testing compared with patients receiving placebo/ChEI. Memantine was well tolerated; most adverse events were mild or moderate. The most common adverse events in the memantine/ChEI group that occurred at a higher rate relative to the placebo/ChEI group were headache (5.6% vs 5.1%, respectively), diarrhea (5.0% vs 3.9%), and dizziness (4.7% vs 1.5%). There were no deaths related to memantine (Table 3).11

Memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may be tolerated better than the IR formulation because of less plasma level fluctuation during the steady-state dosing interval. Also, memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may offer better efficacy over memantine IR, 20 mg/d, because of dose-dependent cognitive, global, and behavioral effects. In addition, once-daily dosing of memantine ER may improve adherence compared with the IR formulation.24

In patients with severe renal impairment, dosage of memantine IR should be reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d.25 However, there is no available information regarding the dosing, safety, and tolerability of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, in patients with renal disease.

Table3

High-dose memantine: Treatment-emergent adverse eventsa

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 335) | Memantine ER (n = 341) |

|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 214 (63.9%) | 214 (62.8%) |

| Fall | 26 (7.8%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (7.2%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Headache | 17 (5.1%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (3.9%) | 17 (5.0%) |

| Dizziness | 5 (1.5%) | 16 (4.7%) |

| Influenza | 9 (2.7%) | 15 (4.4%) |

| Insomnia | 16 (4.8%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Agitation | 15 (4.5%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Hypertension | 8 (2.4%) | 13 (3.8%) |

| Anxiety | 9 (2.7%) | 12 (3.5%) |

| Depression | 5 (1.5%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Weight increased | 3 (0.9%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Constipation | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Somnolence | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Back pain | 2 (0.6%) | 9 (2.6%) |

| Aggression | 5 (1.5%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Hypotension | 5 (1.5%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Vomiting | 4 (1.2%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (0.6%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 10 (3.0%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Confusional state | 7 (2.1%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Weight decreased | 11 (3.3%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Nausea | 7 (2.1%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Irritability | 8 (2.4%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| Cough | 8 (2.4%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| aData [n (%)] include all adverse events experienced by ≥2% patients in either group (safety population). Adverse events that were experienced at twice the rate in 1 group compared with the other are indicated by bold type ER: extended-release (28 mg); TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event Source: Reference 11 | ||

Recommendations

Because there are few FDA-approved treatments for AD, higher doses of donepezil or memantine may be an option for patients who have “maxed out” on their AD therapy or no longer respond to lower doses. Higher doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) could improve medication adherence because both are once-daily preparations. In clinical trials, donepezil, 23 mg/d, was more effective than donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Whether memantine ER, 28 mg/d, is superior to memantine IR, 20 mg/d, needs to be investigated in head-to-head, double-blind, controlled studies.

For patients with moderate to severe AD, donepezil, 23 mg, is associated with greater benefits in cognition compared with donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Similarly, because of potentially superior efficacy because of a higher dose, memantine ER, 28 mg, might best help patients with moderate to severe AD, specifically those who either don’t respond or lose response to memantine IR, 20 mg/d. Combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, with memantine is associated with slower cognitive decline and short and long-term benefits on measures of cognition, activities of daily living, global outcome, and behavior.7,26 However, additional clinical trials are needed to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of combination therapy with higher doses of donepezil and memantine ER.

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers.

- Lleó A, Greenberg SM, Growdon JH. Current pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:513-533.

Drug Brand Names

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Galantamine • Razadyne

- Memantine • Namenda

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Tacrine • Cognex

Disclosures

Dr. Grossberg’s academic department has received research funding from Forest Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer Inc. Dr. Grossberg has received grant/research support from Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, and Pfizer, Inc.; is a consultant to Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Otsuka; and is on the Safety Monitoring Committee for Merck.

Dr. Singh reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Although cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and memantine at standard doses may slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as assessed by cognitive, functional, and global measures, this effect is relatively modest. For the estimated 5.4 million Americans with AD1—more than one-half of whom have moderate to severe disease2—there is a great need for new approaches to slow AD progression.

High doses of donepezil or memantine may be the next step in achieving better results than standard pharmacologic treatments for AD. This article presents the possible benefits and indications for high doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) for managing moderate to severe AD and their safety and tolerability profiles.

Current treatments offer modest benefits

AD treatments comprise 2 categories: ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine (Table 1).3,4 All ChEIs are FDA-approved for mild to moderate AD; donepezil also is approved for severe AD. Memantine is approved for moderate to severe AD, either alone or in combination with ChEIs. Until recently, the maximum FDA-approved doses were donepezil, 10 mg/d, and memantine, 20 mg/d. However, these dosages are associated with only modest beneficial effects in managing cognitive deterioration in patients with moderate to severe dementia.5,6 Studies have reported that combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, and memantine is well tolerated and may result in synergistic benefits by affecting different neurotransmitters in patients with moderate to severe AD.7,8

Recently, the FDA approved higher daily doses of donepezil (23 mg) and memantine (28 mg) for moderate to severe AD on the basis of positive phase III trial results.9-11 Donepezil, 23 mg/d, currently is marketed in the United States; the availability date for memantine, 28 mg/d, was undetermined at press time.

Table 1

FDA-approved treatments for Alzheimer’s disease

| Drug | Maximum daily dose | Mechanism of action | Indication | Common side effects/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrine | 160 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea. First ChEI to be approved, but rarely used because of associated possible hepatotoxicity |

| Donepezil | 10 mg/d | ChEI | All stages of AD | Nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sleep disturbance |

| Rivastigmine | 12 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Galantamine | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Memantine | 20 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| Galantamine ER | 24 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Rivastigmine transdermal system | 9.5 mg/d | ChEI | Mild to moderate AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, loss of appetite |

| Donepezil 23 | 23 mg/d | ChEI | Moderate to severe AD | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Memantine ER | 28 mg/d | NMDA receptor antagonist | Moderate to severe AD | Dizziness, headache, constipation, confusion |

| AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ChEI: cholinesterase inhibitor; ER: extended release; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate Source: References 3,4 | ||||

High-dose donepezil (23 mg/d)

Cognitive decline with AD has been associated with increasing loss of cholinergic neurons and cholinergic activities, particularly in areas associated with memory/cognition and learning, including cortical areas involving the temporal lobe, hippocampus, and nucleus basalis of Meynert.12-14 In addition, evidence suggests that increasing levels of acetylcholine by using ChEIs can enhance cognitive function.13,15

Donepezil is a selective, reversible ChEI believed to enhance central cholinergic function.15 Randomized clinical trials assessing dose-response with donepezil, 5 mg/d and 10 mg/d, have demonstrated more benefit in cognition with either dose than placebo. The 10 mg/d dose was more effective than 5 mg/d in patients with mild to moderate and severe AD.16-18 In patients with advanced AD who are stable on 5 mg/d, increasing to 10 mg/d could slow the progression of cognitive decline.18

Rationale for higher doses. Positron emission tomography studies have shown that at stable doses of donepezil, 5 mg/d or 10 mg/d, average cortical acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition was <30%.19,20 Based on these findings, researchers thought that cortical AChE inhibition may be suboptimal with donepezil, 10 mg/d, and that higher doses of ChEI may be required in patients with more advanced AD—and therefore more cholinergic loss—for adequate cholinesterase inhibition. In a pilot study of patients with mild to moderate AD, higher doses of donepezil (15 mg/d and 20 mg/d) were reported to be safe and well tolerated.21

The 23-mg/d donepezil formulation was developed to provide a higher dose administered once daily without a sharp rise in peak concentration. The FDA approved donepezil, 23 mg/d, for patients with moderate to severe AD on the basis of phase III trial results.9,22 In a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, head-to-head clinical trial, >1,400 patients with moderate to severe AD (Mini-Mental State Exam [MMSE]: 0 to 20) on a stable dose of donepezil, 10 mg/d, for ≥3 months were randomly assigned to receive high-dose donepezil (23 mg/d) or standard-dose donepezil (10 mg/d) for 24 weeks.9,22 Patients in the 23-mg/d group showed a statistically significant improvement in cognition compared with the 10-mg/d group. The difference between groups on a measure of global improvement was not significant.9,22 However, in a post-hoc analysis, it was demonstrated that a subgroup of patients with more severe cognitive impairment (baseline MMSE: 0 to 16), showed significant improvement in cognition as well as global functioning.9

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during the study were higher in patients receiving 23 mg/d (74%) than those receiving 10 mg/d (64%). The most common TEAEs in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups were nausea (12% vs 3%, respectively), vomiting (9% vs 3%), and diarrhea (8% vs 5%) (Table 2).22 These gastrointestinal adverse effects were more frequent during the first month of treatment and were relatively infrequent beyond 1 month. Serious TEAEs, such as falls, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, syncope, aggression, and confusional state, were noted in a similar proportion of patients in the 23-mg/d and 10-mg/d groups; most of these were considered unrelated to treatment. No drug-related deaths occurred during the study. High-dose (23 mg/d) donepezil generally was well tolerated, with a typical ChEI safety profile but superior efficacy.

A recent commentary discussed the issue of effect size and whether a 2.2-point difference on a 100-point scale (the Severe Impairment Battery [SIB]) is clinically meaningful.23 As with all anti-dementia therapies, in any cohort some patients will gain considerably more than 2.2 points on the SIB, which is clinically significant. A 6-month trial is recommended to identify these optimal responders.

Table 2

High-dose vs standard-dose donepezil: Treatment-emergent adverse events

| Adverse event | Donepezil, 23 mg/d | Donepezil,10 mg/d |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 12% | 3% |

| Vomiting | 9% | 3% |

| Diarrhea | 8% | 5% |

| Anorexia | 5% | 2% |

| Dizziness | 5% | 3% |

| Weight decrease | 5% | 3% |

| Headache | 4% | 3% |

| Insomnia | 3% | 2% |

| Urinary incontinence | 3% | 1% |

| Fatigue | 2% | 1% |

| Weakness | 2% | 1% |

| Somnolence | 2% | 1% |

| Contusion | 2% | 0% |

| Source: Reference 22 | ||

High-dose memantine

Memantine is an NMDA receptor antagonist, which works on glutamate, an ubiquitous neurotransmitter in the brain that serves many functions. For reasons that are not fully understood, in AD glutamate becomes excitotoxic and causes neuronal death.

Some researchers have hypothesized that if safe and well tolerated, a memantine dose >20 mg/d may have better efficacy than a lower dose. Memantine’s manufacturer has developed an extended-release (ER), once-daily formulation of memantine, 28 mg/d, to improve adherence and possibly increase efficacy.10,11 Because of memantine ER’s relatively slow absorption rate and longer median Tmax, of 12 hours, there is minimal fluctuation in plasma levels during steady-state dosing intervals compared with the immediate-release (IR) formulation.10

In a phase I study of 24 healthy volunteers that investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, TEAEs were mild; the most common were headache, somnolence, and dizziness.10 During memantine treatment, there were no serious adverse events, potential significant changes in patients’ vital signs, or deaths.

Memantine ER plus ChEI. A multicenter, multinational, randomized, double-blind study compared memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and placebo in patients with moderate to severe AD (MMSE: 3 to 14).11 All patients were receiving concurrent, stable ChEI treatment (donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine) for ≥3 months before the study. Patients treated with memantine ER, 28 mg/d, and ChEI (n = 342) showed a significant improvement compared with the placebo/ChEI group (n = 335) in cognition and global functioning. Patients receiving memantine/ChEI also showed statistically significant benefits on behavior and verbal fluency testing compared with patients receiving placebo/ChEI. Memantine was well tolerated; most adverse events were mild or moderate. The most common adverse events in the memantine/ChEI group that occurred at a higher rate relative to the placebo/ChEI group were headache (5.6% vs 5.1%, respectively), diarrhea (5.0% vs 3.9%), and dizziness (4.7% vs 1.5%). There were no deaths related to memantine (Table 3).11

Memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may be tolerated better than the IR formulation because of less plasma level fluctuation during the steady-state dosing interval. Also, memantine ER, 28 mg/d, may offer better efficacy over memantine IR, 20 mg/d, because of dose-dependent cognitive, global, and behavioral effects. In addition, once-daily dosing of memantine ER may improve adherence compared with the IR formulation.24

In patients with severe renal impairment, dosage of memantine IR should be reduced from 20 mg/d to 10 mg/d.25 However, there is no available information regarding the dosing, safety, and tolerability of memantine ER, 28 mg/d, in patients with renal disease.

Table3

High-dose memantine: Treatment-emergent adverse eventsa

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 335) | Memantine ER (n = 341) |

|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 214 (63.9%) | 214 (62.8%) |

| Fall | 26 (7.8%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (7.2%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Headache | 17 (5.1%) | 19 (5.6%) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (3.9%) | 17 (5.0%) |

| Dizziness | 5 (1.5%) | 16 (4.7%) |

| Influenza | 9 (2.7%) | 15 (4.4%) |

| Insomnia | 16 (4.8%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Agitation | 15 (4.5%) | 14 (4.1%) |

| Hypertension | 8 (2.4%) | 13 (3.8%) |

| Anxiety | 9 (2.7%) | 12 (3.5%) |

| Depression | 5 (1.5%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Weight increased | 3 (0.9%) | 11 (3.2%) |

| Constipation | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Somnolence | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (2.9%) |

| Back pain | 2 (0.6%) | 9 (2.6%) |

| Aggression | 5 (1.5%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Hypotension | 5 (1.5%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Vomiting | 4 (1.2%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (0.6%) | 7 (2.1%) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 10 (3.0%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Confusional state | 7 (2.1%) | 6 (1.8%) |

| Weight decreased | 11 (3.3%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Nausea | 7 (2.1%) | 5 (1.5%) |

| Irritability | 8 (2.4%) | 4 (1.2%) |

| Cough | 8 (2.4%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| aData [n (%)] include all adverse events experienced by ≥2% patients in either group (safety population). Adverse events that were experienced at twice the rate in 1 group compared with the other are indicated by bold type ER: extended-release (28 mg); TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event Source: Reference 11 | ||

Recommendations

Because there are few FDA-approved treatments for AD, higher doses of donepezil or memantine may be an option for patients who have “maxed out” on their AD therapy or no longer respond to lower doses. Higher doses of donepezil (23 mg/d) and memantine (28 mg/d) could improve medication adherence because both are once-daily preparations. In clinical trials, donepezil, 23 mg/d, was more effective than donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Whether memantine ER, 28 mg/d, is superior to memantine IR, 20 mg/d, needs to be investigated in head-to-head, double-blind, controlled studies.

For patients with moderate to severe AD, donepezil, 23 mg, is associated with greater benefits in cognition compared with donepezil, 10 mg/d.9 Similarly, because of potentially superior efficacy because of a higher dose, memantine ER, 28 mg, might best help patients with moderate to severe AD, specifically those who either don’t respond or lose response to memantine IR, 20 mg/d. Combining a ChEI, such as donepezil, with memantine is associated with slower cognitive decline and short and long-term benefits on measures of cognition, activities of daily living, global outcome, and behavior.7,26 However, additional clinical trials are needed to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of combination therapy with higher doses of donepezil and memantine ER.

Related Resources

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers.

- Lleó A, Greenberg SM, Growdon JH. Current pharmacotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:513-533.

Drug Brand Names

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Galantamine • Razadyne

- Memantine • Namenda

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Tacrine • Cognex

Disclosures

Dr. Grossberg’s academic department has received research funding from Forest Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer Inc. Dr. Grossberg has received grant/research support from Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, and Pfizer, Inc.; is a consultant to Baxter BioScience, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Novartis, and Otsuka; and is on the Safety Monitoring Committee for Merck.

Dr. Singh reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alzheimer’s Association, Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(2):208-244.

2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119-1122.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. Alzheimer’s disease medications. http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-disease-medications-fact-sheet. Accessed May 10 2012.

4. Osborn GG, Saunders AV. Current treatments for patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(9 suppl 8):S16-S26.

5. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379-397.

6. Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):56-67.

7. Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(3):317-324.

8. Xiong G, Doraiswamy PM. Combination drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: what is evidence-based and what is not? Geriatrics. 2005;60(6):22-26.

9. Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of high (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1234-1251.

10. Periclou A, Hu Y. Extended-release memantine capsule (28 mg once daily): a multiple dose, open-label study evaluating steady-state pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

11. Grossberg GT, Manes F, Allegri R, et al. A multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial of memantine extended-release capsule (28 mg, once daily) in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

12. Geula C, Mesulam MM. Systematic regional variations in the loss of cortical cholinergic fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6(2):165-177.

13. Whitehouse PJ. The cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 13):19-22.

14. Teipel SJ, Flatz WH, Heinsen H, et al. Measurement of basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. Brain. 2005;128(11):2626-2644.

15. Shintani EY, Uchida KM. Donepezil: an anticholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(24):2805-2810.

16. Homma A, Imai Y, Tago H, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease in a Japanese population: results from a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(5):399-407.

17. Whitehead A, Perdomo C, Pratt RD, et al. Donepezil for the symptomatic treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):624-633.

18. Nozawa M, Ichimiya Y, Nozawa E, et al. Clinical effects of high oral dose of donepezil for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):50-55.

19. Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Frey KA, et al. Limited donepezil inhibition of acetylcholinesterase measured with positron emission tomography in living Alzheimer cerebral cortex. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(3):391-395.

20. Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, et al. Degree of inhibition of cortical acetylcholinesterase activity and cognitive effects by donepezil treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(3):315-319.

21. Doody RS, Corey-Bloom J, Zhang R, et al. Safety and tolerability of donepezil at doses up to 20 mg/day: results from a pilot study in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(2):163-174.

22. Aricept [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake NJ: Eisai Co.; 2012.

23. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. How the FDA forgot the evidence: the case of donepezil 23 mg. BMJ. 2012;344:e1086.-doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1086.

24. Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):e22-e33.

25. Periclou A, Ventura D, Rao N, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of memantine in healthy and renally impaired subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(1):134-143.

26. Atri A, Shaughnessy LW, Locascio JJ, et al. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(3):209-221.

1. Alzheimer’s Association, Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(2):208-244.

2. Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119-1122.

3. Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center. Alzheimer’s disease medications. http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-disease-medications-fact-sheet. Accessed May 10 2012.

4. Osborn GG, Saunders AV. Current treatments for patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(9 suppl 8):S16-S26.

5. Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, et al. Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(5):379-397.

6. Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):56-67.

7. Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(3):317-324.

8. Xiong G, Doraiswamy PM. Combination drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: what is evidence-based and what is not? Geriatrics. 2005;60(6):22-26.

9. Farlow MR, Salloway S, Tariot PN, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of high (23 mg/d) versus standard-dose (10 mg/d) donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind study. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1234-1251.

10. Periclou A, Hu Y. Extended-release memantine capsule (28 mg once daily): a multiple dose, open-label study evaluating steady-state pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

11. Grossberg GT, Manes F, Allegri R, et al. A multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial of memantine extended-release capsule (28 mg, once daily) in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Poster presented at 11th International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; July 26-31, 2008; Chicago, IL.

12. Geula C, Mesulam MM. Systematic regional variations in the loss of cortical cholinergic fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6(2):165-177.

13. Whitehouse PJ. The cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 13):19-22.

14. Teipel SJ, Flatz WH, Heinsen H, et al. Measurement of basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. Brain. 2005;128(11):2626-2644.

15. Shintani EY, Uchida KM. Donepezil: an anticholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(24):2805-2810.

16. Homma A, Imai Y, Tago H, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease in a Japanese population: results from a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(5):399-407.

17. Whitehead A, Perdomo C, Pratt RD, et al. Donepezil for the symptomatic treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(7):624-633.

18. Nozawa M, Ichimiya Y, Nozawa E, et al. Clinical effects of high oral dose of donepezil for patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(2):50-55.

19. Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Frey KA, et al. Limited donepezil inhibition of acetylcholinesterase measured with positron emission tomography in living Alzheimer cerebral cortex. Ann Neurol. 2000;48(3):391-395.

20. Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Hendrickson R, et al. Degree of inhibition of cortical acetylcholinesterase activity and cognitive effects by donepezil treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(3):315-319.

21. Doody RS, Corey-Bloom J, Zhang R, et al. Safety and tolerability of donepezil at doses up to 20 mg/day: results from a pilot study in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(2):163-174.

22. Aricept [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake NJ: Eisai Co.; 2012.

23. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. How the FDA forgot the evidence: the case of donepezil 23 mg. BMJ. 2012;344:e1086.-doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1086.

24. Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):e22-e33.

25. Periclou A, Ventura D, Rao N, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of memantine in healthy and renally impaired subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79(1):134-143.

26. Atri A, Shaughnessy LW, Locascio JJ, et al. Long-term course and effectiveness of combination therapy in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(3):209-221.

Does bupropion exacerbate anxiety?

For many clinicians, bupropion is the “go-to” medication for treating depressed patients who smoke, have concerns about sexual dysfunction side effects, and/or worry about weight gain. Bupropion is FDA-approved for preventing seasonal major depressive episodes in patients with seasonal affective disorder and is indicated as a smoking cessation aid.

“Anxious depression”—defined as depression with high levels of anxiety—is associated with poorer outcomes than “non-anxious” depression.1 Prescribing medications for these patients can be challenging. Some clinicians believe that bupropion exacerbates anxiety and should not be used to treat patients who experience both anxiety and depression.

Reports from our patients and our cumulative clinical experience are key factors in developing expertise in selecting appropriate medications. When informing our patients about what to expect from medications, however, it can be useful to combine anecdotal evidence with knowledge of the facts or lack thereof. Are there data to support or contradict the idea that bupropion can cause anxiety while treating depression?

What the research shows

The drug manufacturer reports a “substantial proportion of patients treated with Wellbutrin experience some degree of increased restlessness, agitation, anxiety, and insomnia, especially shortly after initiation of treatment.”2

In 2001, Rush et al3 published the results of a 16-week study (n=248) assessing pre-treatment anxiety levels and response to sertraline or bupropion. The authors concluded that anxious and depressed patients who received sertraline didn’t experience a superior anxiolytic or antidepressant response compared with bupropion.3 The same authors came to similar conclusions in a retrospective analysis of a pair of 8-week randomized, controlled, double-blind trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and bupropion.4

In 2001, Nieuwstraten et al5 compared bupropion with SSRIs for treating depression by reviewing several randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The relative risk of developing “anxiety/agitation” was 1.32 (95% confidence interval, 0.85 to 2.04), which was not statistically significant.

In a 2008 meta-analysis, Papakostas et al6 pooled individual patient data from 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Their aim was to compare the efficacy of bupropion to SSRIs in treating “anxious depression.” They found no difference in timing or degree of improvement in anxiety symptoms between groups based on Hamilton Anxiety Scale or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—Anxiety-Somatization (HDRS-AS) scores. The authors recommended that antidepressant choice should not be based on concerns about worsening anxiety symptoms in depressed patients.6

Another meta-analysis by Papakostas et al7 of the same 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials suggested SSRIs may confer an advantage over bupropion in treating a subset of patients with “anxious depression,” which they defined as a HDRS-AS score ≥7. The authors noted the advantage was statistically significant, although “modest.”

Other smaller studies suggest that bupropion does not increase anxiety.8,9 A pilot study (N = 24, no placebo control) concluded that bupropion XL was comparable to escitalopram in treating anxiety in outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder.8

Because designing and executing drug trials can be expensive, it is not surprising that most of the evidence cited above derives from pharmaceutical company-sponsored or industry-affiliated work. As such, we should evaluate available evidence within the context of what we hear from and observe in our patients.

Our opinion

When assessing patients with depression and anxiety, we must carefully evaluate symptoms to distinguish between depression with associated anxiety symptoms and depression with a comorbid anxiety disorder.

If a patient suffers from depression with associated anxiety symptoms (“anxious depression”), keep in mind that although some data demonstrate a superior response to SSRIs, other studies show no difference in effect. Some research—albeit smaller, less compelling studies—suggests that bupropion may decrease anxiety.

If your patient suffers from comorbid depression and an anxiety disorder, bupropion would not be a first-line choice because it is not FDA-approved to treat anxiety disorders. Although it is possible that anxiety/agitation could result from bupropion use, there is not sufficient data to support its reputation as ”anxiogenic.”

What is your experience?

Do you agree with the authors? Send comments to [email protected] or share your thoughts on http://www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry.

Related Resource

- American Psychiatric Association. Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:780-781.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):342-351.

2. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

3. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, et al. Response in relation to baseline anxiety levels in major depressive disorder treated with bupropion sustained release or sertraline. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):131-138.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, et al. Do bupropion SR and sertraline differ in their effects on anxiety in depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(10):776-781.

5. Nieuwstraten CE, Dolovich LR. Bupropion versus selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors for treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(12):1608-1613.

6. Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH, Alpert JE, et al. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 10 double-blind, randomized clinical trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(2):134-140.

7. Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, et al. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1287-1292.

8. Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Feusner JD, et al. A pilot controlled trial of bupropion XL versus escitalopram in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):46-51.

9. Feighner JP, Gardner EA, Johnston JA, et al. Double-blind comparison of bupropion and fluoxetine in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(8):329-335.

For many clinicians, bupropion is the “go-to” medication for treating depressed patients who smoke, have concerns about sexual dysfunction side effects, and/or worry about weight gain. Bupropion is FDA-approved for preventing seasonal major depressive episodes in patients with seasonal affective disorder and is indicated as a smoking cessation aid.

“Anxious depression”—defined as depression with high levels of anxiety—is associated with poorer outcomes than “non-anxious” depression.1 Prescribing medications for these patients can be challenging. Some clinicians believe that bupropion exacerbates anxiety and should not be used to treat patients who experience both anxiety and depression.

Reports from our patients and our cumulative clinical experience are key factors in developing expertise in selecting appropriate medications. When informing our patients about what to expect from medications, however, it can be useful to combine anecdotal evidence with knowledge of the facts or lack thereof. Are there data to support or contradict the idea that bupropion can cause anxiety while treating depression?

What the research shows

The drug manufacturer reports a “substantial proportion of patients treated with Wellbutrin experience some degree of increased restlessness, agitation, anxiety, and insomnia, especially shortly after initiation of treatment.”2

In 2001, Rush et al3 published the results of a 16-week study (n=248) assessing pre-treatment anxiety levels and response to sertraline or bupropion. The authors concluded that anxious and depressed patients who received sertraline didn’t experience a superior anxiolytic or antidepressant response compared with bupropion.3 The same authors came to similar conclusions in a retrospective analysis of a pair of 8-week randomized, controlled, double-blind trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and bupropion.4

In 2001, Nieuwstraten et al5 compared bupropion with SSRIs for treating depression by reviewing several randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The relative risk of developing “anxiety/agitation” was 1.32 (95% confidence interval, 0.85 to 2.04), which was not statistically significant.

In a 2008 meta-analysis, Papakostas et al6 pooled individual patient data from 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Their aim was to compare the efficacy of bupropion to SSRIs in treating “anxious depression.” They found no difference in timing or degree of improvement in anxiety symptoms between groups based on Hamilton Anxiety Scale or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—Anxiety-Somatization (HDRS-AS) scores. The authors recommended that antidepressant choice should not be based on concerns about worsening anxiety symptoms in depressed patients.6

Another meta-analysis by Papakostas et al7 of the same 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials suggested SSRIs may confer an advantage over bupropion in treating a subset of patients with “anxious depression,” which they defined as a HDRS-AS score ≥7. The authors noted the advantage was statistically significant, although “modest.”

Other smaller studies suggest that bupropion does not increase anxiety.8,9 A pilot study (N = 24, no placebo control) concluded that bupropion XL was comparable to escitalopram in treating anxiety in outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder.8

Because designing and executing drug trials can be expensive, it is not surprising that most of the evidence cited above derives from pharmaceutical company-sponsored or industry-affiliated work. As such, we should evaluate available evidence within the context of what we hear from and observe in our patients.

Our opinion

When assessing patients with depression and anxiety, we must carefully evaluate symptoms to distinguish between depression with associated anxiety symptoms and depression with a comorbid anxiety disorder.

If a patient suffers from depression with associated anxiety symptoms (“anxious depression”), keep in mind that although some data demonstrate a superior response to SSRIs, other studies show no difference in effect. Some research—albeit smaller, less compelling studies—suggests that bupropion may decrease anxiety.

If your patient suffers from comorbid depression and an anxiety disorder, bupropion would not be a first-line choice because it is not FDA-approved to treat anxiety disorders. Although it is possible that anxiety/agitation could result from bupropion use, there is not sufficient data to support its reputation as ”anxiogenic.”

What is your experience?

Do you agree with the authors? Send comments to [email protected] or share your thoughts on http://www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry.

Related Resource

- American Psychiatric Association. Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:780-781.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

For many clinicians, bupropion is the “go-to” medication for treating depressed patients who smoke, have concerns about sexual dysfunction side effects, and/or worry about weight gain. Bupropion is FDA-approved for preventing seasonal major depressive episodes in patients with seasonal affective disorder and is indicated as a smoking cessation aid.

“Anxious depression”—defined as depression with high levels of anxiety—is associated with poorer outcomes than “non-anxious” depression.1 Prescribing medications for these patients can be challenging. Some clinicians believe that bupropion exacerbates anxiety and should not be used to treat patients who experience both anxiety and depression.

Reports from our patients and our cumulative clinical experience are key factors in developing expertise in selecting appropriate medications. When informing our patients about what to expect from medications, however, it can be useful to combine anecdotal evidence with knowledge of the facts or lack thereof. Are there data to support or contradict the idea that bupropion can cause anxiety while treating depression?

What the research shows

The drug manufacturer reports a “substantial proportion of patients treated with Wellbutrin experience some degree of increased restlessness, agitation, anxiety, and insomnia, especially shortly after initiation of treatment.”2

In 2001, Rush et al3 published the results of a 16-week study (n=248) assessing pre-treatment anxiety levels and response to sertraline or bupropion. The authors concluded that anxious and depressed patients who received sertraline didn’t experience a superior anxiolytic or antidepressant response compared with bupropion.3 The same authors came to similar conclusions in a retrospective analysis of a pair of 8-week randomized, controlled, double-blind trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and bupropion.4

In 2001, Nieuwstraten et al5 compared bupropion with SSRIs for treating depression by reviewing several randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The relative risk of developing “anxiety/agitation” was 1.32 (95% confidence interval, 0.85 to 2.04), which was not statistically significant.

In a 2008 meta-analysis, Papakostas et al6 pooled individual patient data from 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Their aim was to compare the efficacy of bupropion to SSRIs in treating “anxious depression.” They found no difference in timing or degree of improvement in anxiety symptoms between groups based on Hamilton Anxiety Scale or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale—Anxiety-Somatization (HDRS-AS) scores. The authors recommended that antidepressant choice should not be based on concerns about worsening anxiety symptoms in depressed patients.6

Another meta-analysis by Papakostas et al7 of the same 10 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials suggested SSRIs may confer an advantage over bupropion in treating a subset of patients with “anxious depression,” which they defined as a HDRS-AS score ≥7. The authors noted the advantage was statistically significant, although “modest.”

Other smaller studies suggest that bupropion does not increase anxiety.8,9 A pilot study (N = 24, no placebo control) concluded that bupropion XL was comparable to escitalopram in treating anxiety in outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder.8

Because designing and executing drug trials can be expensive, it is not surprising that most of the evidence cited above derives from pharmaceutical company-sponsored or industry-affiliated work. As such, we should evaluate available evidence within the context of what we hear from and observe in our patients.

Our opinion

When assessing patients with depression and anxiety, we must carefully evaluate symptoms to distinguish between depression with associated anxiety symptoms and depression with a comorbid anxiety disorder.

If a patient suffers from depression with associated anxiety symptoms (“anxious depression”), keep in mind that although some data demonstrate a superior response to SSRIs, other studies show no difference in effect. Some research—albeit smaller, less compelling studies—suggests that bupropion may decrease anxiety.

If your patient suffers from comorbid depression and an anxiety disorder, bupropion would not be a first-line choice because it is not FDA-approved to treat anxiety disorders. Although it is possible that anxiety/agitation could result from bupropion use, there is not sufficient data to support its reputation as ”anxiogenic.”

What is your experience?

Do you agree with the authors? Send comments to [email protected] or share your thoughts on http://www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry.

Related Resource

- American Psychiatric Association. Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:780-781.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):342-351.

2. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

3. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, et al. Response in relation to baseline anxiety levels in major depressive disorder treated with bupropion sustained release or sertraline. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):131-138.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, et al. Do bupropion SR and sertraline differ in their effects on anxiety in depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(10):776-781.

5. Nieuwstraten CE, Dolovich LR. Bupropion versus selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors for treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(12):1608-1613.

6. Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH, Alpert JE, et al. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 10 double-blind, randomized clinical trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(2):134-140.

7. Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, et al. Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1287-1292.

8. Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Feusner JD, et al. A pilot controlled trial of bupropion XL versus escitalopram in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2008;41(1):46-51.

9. Feighner JP, Gardner EA, Johnston JA, et al. Double-blind comparison of bupropion and fluoxetine in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52(8):329-335.

1. Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):342-351.

2. Wellbutrin [package insert]. Research Triangle Park NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2008.

3. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Carmody TJ, et al. Response in relation to baseline anxiety levels in major depressive disorder treated with bupropion sustained release or sertraline. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):131-138.

4. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Carmody TJ, et al. Do bupropion SR and sertraline differ in their effects on anxiety in depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(10):776-781.

5. Nieuwstraten CE, Dolovich LR. Bupropion versus selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors for treatment of depression. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(12):1608-1613.