User login

Prevalence of Undiagnosed Diabetes in US

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Resident Education, Feedback, Incentives Improve Patient Satisfaction

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

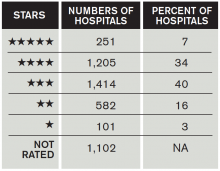

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Hospitalists Play Vital Role in Patients’ View of Hospital Stay

Special Reports

Hospitalists are often perceived as the face of the hospital, whether that is their official responsibility or not. They are on the front lines of hearing, seeing, and understanding where gaps exist in a patient’s experience.

“Whenever I hear a patient complain, I can almost piece together what happened without having to interview other staff,” says Jairy C. Hunter III, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate CMO for care transitions at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Up to this point, there hasn’t been as much accountability regarding customer satisfaction in our industry compared to other industries,” Dr. Hunter says.

The paradigm shift has occurred because payers are demanding it. They want value and satisfaction in what they are paying for. In fact, there is a movement to try to standardize procedures whenever possible, such as the amount of time it takes someone to answer a call bell or the volume of noise in a hallway.

“Patients are being asked questions about such topics in surveys,” Dr. Hunter says. “Although these types of questions don’t involve medical decision-making or a course of treatment, they do include personal interactions that influence how patients feel about their hospital experience.”

Another reason for the shift is the significant increase in the use of electronic communication devices and the explosion of online ratings of consumer products and services. Naturally, consumers want access to accurate and easy-to-use information about the quality of healthcare services.

Patient experience surveys focus on how patients’ experienced or perceived key aspects of their care, not how satisfied they were with their care.1 One way a hospital can measure patient experience is with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which was developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).2 Although other patient satisfaction/experience vendors offer surveys, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 states that all Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems (IPPS) hospitals who wish to receive their full annual payment update must collect and submit HCAHPS data to CMS.

The HCAHPS survey, which employs standardized survey instrument and data collection methodology to measure patients’ perspectives on hospital care, is administered to a random sample of patients throughout the year. CMS cleans, adjusts, and analyzes the data and then publicly reports the results. All CAHPS products are available at no cost at www.cahps.ahrq.gov.2

Christine Crofton, PhD, director of CAHPS in Rockville, Md., notes that the HCAHPS survey focuses on patient experience measures because they are considered more understandable, unambiguous, actionable, and objective compared to general satisfaction ratings. Although CAHPS surveys do ask respondents to provide overall ratings (e.g. rate the physician on a scale of one to 10), their primary focus is to ask patients to report on their experiences with specific aspects of care in order to provide information that is not biased by different expectations.

For example, if a patient doesn’t understand what symptoms or problems to report to his or her provider after leaving the hospital, the lack of understanding could lead to a complication, a worsening condition, or readmission.

“A specific survey question about written discharge instructions will give hospital administrators more actionable information concerning an increase in readmission rates than a response to a 10-point satisfaction scale,” Dr. Crofton explains.

Efforts to Improve

At medical institutions across the nation, hospitalists and their team members are making conscious efforts to improve the patient experience in light of the growing importance of surveys. Baylor Scott and White Health in Round Rock, Texas, offers a lecture series and provider coaching as part of its continuing education program. The training, says Trina E. Dorrah, MD, MPH, a BSWH hospitalist and physician director for quality improvement, encompasses such topics as:

- Dealing with difficult patient scenarios;

- Patient experience improvement tips;

- Tips to improve providers’ explanations; and

- Tips to improve patients’ understanding.

Dr. Dorrah uses one-on-one shadowing to help providers improve the patient experience.

“I accompany the provider when visiting the patient and observe his or her interactions,” she says. “This enables me to help providers to see what skills they can incorporate to positively impact patient experience.”

Interdisciplinary rounds have also helped to improve the patient experience.

“Patients want to know that their entire healthcare team is focused on them and that they are working together to improve their experience,” Dr. Dorrah says. On weekdays, hospitalists lead interdisciplinary rounds with the rest of the care team, including case management, nursing, and therapy. “We discuss our patients and ensure that we are all on the same page regarding the plan.”

In addition, hospitalists round with nurses each morning. “Everyone benefits,” Dr. Dorrah says. “The patient gets more coordinated care and the nurse is better educated about the plan of care for the day. The number of pages from the nurse to the physician is also reduced because the nurse better understands the care plan.”

BSWH, which uses Press Ganey Associates to administer HCAHPS surveys, considers the scores for the doctor communication domain when establishing a hospitalist team goal for the year.

“If our team reaches the goal, the leadership/administrative team rewards the hospitalist team with a financial bonus,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Lawrence General Hospital, in Lawrence, Mass., which also uses Press Ganey Associates to administer and manage its HCAHPS satisfaction surveys, is working to increase the ability of hospitalists and other caregivers to proactively meet and exceed patients’ needs with its Five-to-Thrive program. The program consists of these five strategies:

- Care-Out-Loud: an initiative that charges every clinical and nonclinical staff member to be present, sensitive, and compassionate to the patient and explain each step of the clinical interaction;

- Manager rounding on staff and patients;

- Hourly staff rounding on patients;

- Interdisciplinary bedside rounding; and

- Senior leader rounding.

“It is based on best practice tactics that aim to improve the overall patient and family experience,” says Damaris Valera, MS, CMPE, director of the hospital’s Service Excellence Program.

Cogent Healthcare at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla., places a large emphasis on AIDET principles—acknowledge, introduce, duration, explanation, and thank you—during each patient encounter, says Larry Sharp, MD, SFHM, system medical director. AIDET principles entail offering a pleasant greeting and introducing yourself to patients, keeping patients abreast of wait times, explaining procedures, and thanking patients for the opportunity to participate in their care.

The medical director makes shadow rounds with providers and then ghost rounds by surveying the patients after rounds to get the patients’ direct feedback about encounters.

“We provide information to our providers from these rounds as a method to improve care,” Dr. Sharp says.

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago trains hospitalists on communication skills and consequently saw a trend toward improved satisfaction scores and used physician face cards to improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of physicians, which did not impact patient satisfaction, reports Kevin J. O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, associate professor of medicine, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and associate chair for quality in the department of medicine at Northwestern.3,4 Findings were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“These efforts have reinforced the need for multifaceted interventions,” Dr. O’Leary says. “Alone, each one has had little effect, but combined they may have a greater effect. The data is intended to be formative and to identify opportunities to learn.”

Additional improvements have been made due to a better understanding of drivers of low satisfaction.

“Unit medical directors [hospitalists] have started to visit patients to get a qualitative sense of what things affect patient experience,” Dr. O’Leary says. As a result, two previously unidentified issues—ED personnel making promises that can’t be kept to patients and patients receiving conflicting information from specialist consultants and hospitalists—surfaced which could now be addressed.”

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their best efforts to improve the patient experience, hospitalists face myriad obstacles. First, the HCAHPS survey asks about the collective care delivered by doctors during the hospitalization, as opposed to the care given by one particular hospitalist.

“One challenge hospitalists face by not having individual data is not knowing which hospitalists excel at the patient experience and which ones do not,” Dr. Dorrah says. “When no one feels that he or she is the problem, it is difficult to hold individual hospitalists accountable.”

Another problem, Dr. Dorrah reports, stems from the fact that patients may see more than one physician—perhaps several hospitalists or specialists—during their hospitalization. When the HCAHPS survey asks patients to assess the care given by all physicians, patients consider the care given by multiple different physicians.

“Therefore, it is difficult to hold a particular hospitalist accountable for the physician communication domain when he or she is not the only provider influencing patients’ perceptions.”

Some hospital systems still have chosen to attribute HCAHPS doctor communication scores to individual hospitalists. These health systems address the issue by attributing the survey results to the admitting physician, the discharging physician, or all hospitalists who participated in the patient’s care.

“None of these methods are perfect, but health systems are increasingly wanting to ensure their inpatient providers are as invested in the patient experience as their outpatient physicians,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Another obstacle hospitalist groups face is the fact that more attention is given to raising HCAHPS survey scores than to improving the overall patient experience.

“In an effort to raise survey scores, hospitals often lose sight of what truly matters to patients,” Dr. Dorrah says. “Many things contribute to a positive or negative patient experience that are not necessarily measured by the survey. If you only pay attention to the survey, your hospital may overlook things that truly matter to your patients.”

Finally, with the increasing focus on the patient experience, the focus on maintaining a good provider experience can fall short.

“While it’s tempting to ask hospitalists to do more—see more patients, take on more responsibility, and participate in more committees—if hospitals fail to provide a positive environment for their hospitalists, they will have a difficult time fully engaging their hospitalists with the patient experience,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Some situations are out of the hospitalists’ hands. A patient may get upset or angry, and the cause is outside of anyone’s control.

“They may have to spend a night in the emergency department or have an unfavorable outcome,” Dr. Hunter says. “In those instances, employ the art of personal interaction—try to empathize with patients and let them know that you care about them.”

Another limitation, Dr. Sharp says, is that you can’t specifically script encounters to “teach to the test,” by using verbiage with the patient that is verbatim from the satisfaction survey questions.

“Nor can we directly control the temperature in patients’ rooms or the quality of their food,” he says. “We also do not have direct control over a negative experience in the emergency department before patients are referred to us, and many surveys show that it is very difficult to overcome a bad experience.”

Tools at Your Fingertips

As a result of the growing emphasis on patient-centered care, SHM created a Patient Experience Committee this year. SHM defines patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.” The committee is looking at the issues at hand and defining the patient experience and what makes it good.

“We are looking at success stories, as well as not so successful stories, from some of our members to identify what seems to work and what doesn’t work,” says Dr. Sharp, a member of the committee. “By identifying best practices, we can then share this knowledge with the rest of the society, along with methods to implement these practices. We can centralize the gathered knowledge and data and then analyze and make it available to SHM members for their implementation and use.”

The hospitalist plays a key role in the patient experience. Now, more than ever, it’s important to do what you can to make it positive. Consider initiatives you might want to participate in—and perhaps even start your own.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS). CMS.gov. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- Survey of patients’ experiences (HCAHPS). Medicare.gov/Hospital Compare. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- O’Leary KJ, Darling TA, Rauworth J, Williams MV. Impact of hospitalist communication-skills training on patient-satisfaction scores. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):315-320.

- Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospital physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

Special Reports

Hospitalists are often perceived as the face of the hospital, whether that is their official responsibility or not. They are on the front lines of hearing, seeing, and understanding where gaps exist in a patient’s experience.

“Whenever I hear a patient complain, I can almost piece together what happened without having to interview other staff,” says Jairy C. Hunter III, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate CMO for care transitions at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Up to this point, there hasn’t been as much accountability regarding customer satisfaction in our industry compared to other industries,” Dr. Hunter says.

The paradigm shift has occurred because payers are demanding it. They want value and satisfaction in what they are paying for. In fact, there is a movement to try to standardize procedures whenever possible, such as the amount of time it takes someone to answer a call bell or the volume of noise in a hallway.

“Patients are being asked questions about such topics in surveys,” Dr. Hunter says. “Although these types of questions don’t involve medical decision-making or a course of treatment, they do include personal interactions that influence how patients feel about their hospital experience.”

Another reason for the shift is the significant increase in the use of electronic communication devices and the explosion of online ratings of consumer products and services. Naturally, consumers want access to accurate and easy-to-use information about the quality of healthcare services.

Patient experience surveys focus on how patients’ experienced or perceived key aspects of their care, not how satisfied they were with their care.1 One way a hospital can measure patient experience is with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which was developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).2 Although other patient satisfaction/experience vendors offer surveys, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 states that all Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems (IPPS) hospitals who wish to receive their full annual payment update must collect and submit HCAHPS data to CMS.

The HCAHPS survey, which employs standardized survey instrument and data collection methodology to measure patients’ perspectives on hospital care, is administered to a random sample of patients throughout the year. CMS cleans, adjusts, and analyzes the data and then publicly reports the results. All CAHPS products are available at no cost at www.cahps.ahrq.gov.2

Christine Crofton, PhD, director of CAHPS in Rockville, Md., notes that the HCAHPS survey focuses on patient experience measures because they are considered more understandable, unambiguous, actionable, and objective compared to general satisfaction ratings. Although CAHPS surveys do ask respondents to provide overall ratings (e.g. rate the physician on a scale of one to 10), their primary focus is to ask patients to report on their experiences with specific aspects of care in order to provide information that is not biased by different expectations.

For example, if a patient doesn’t understand what symptoms or problems to report to his or her provider after leaving the hospital, the lack of understanding could lead to a complication, a worsening condition, or readmission.

“A specific survey question about written discharge instructions will give hospital administrators more actionable information concerning an increase in readmission rates than a response to a 10-point satisfaction scale,” Dr. Crofton explains.

Efforts to Improve

At medical institutions across the nation, hospitalists and their team members are making conscious efforts to improve the patient experience in light of the growing importance of surveys. Baylor Scott and White Health in Round Rock, Texas, offers a lecture series and provider coaching as part of its continuing education program. The training, says Trina E. Dorrah, MD, MPH, a BSWH hospitalist and physician director for quality improvement, encompasses such topics as:

- Dealing with difficult patient scenarios;

- Patient experience improvement tips;

- Tips to improve providers’ explanations; and

- Tips to improve patients’ understanding.

Dr. Dorrah uses one-on-one shadowing to help providers improve the patient experience.

“I accompany the provider when visiting the patient and observe his or her interactions,” she says. “This enables me to help providers to see what skills they can incorporate to positively impact patient experience.”

Interdisciplinary rounds have also helped to improve the patient experience.

“Patients want to know that their entire healthcare team is focused on them and that they are working together to improve their experience,” Dr. Dorrah says. On weekdays, hospitalists lead interdisciplinary rounds with the rest of the care team, including case management, nursing, and therapy. “We discuss our patients and ensure that we are all on the same page regarding the plan.”

In addition, hospitalists round with nurses each morning. “Everyone benefits,” Dr. Dorrah says. “The patient gets more coordinated care and the nurse is better educated about the plan of care for the day. The number of pages from the nurse to the physician is also reduced because the nurse better understands the care plan.”

BSWH, which uses Press Ganey Associates to administer HCAHPS surveys, considers the scores for the doctor communication domain when establishing a hospitalist team goal for the year.

“If our team reaches the goal, the leadership/administrative team rewards the hospitalist team with a financial bonus,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Lawrence General Hospital, in Lawrence, Mass., which also uses Press Ganey Associates to administer and manage its HCAHPS satisfaction surveys, is working to increase the ability of hospitalists and other caregivers to proactively meet and exceed patients’ needs with its Five-to-Thrive program. The program consists of these five strategies:

- Care-Out-Loud: an initiative that charges every clinical and nonclinical staff member to be present, sensitive, and compassionate to the patient and explain each step of the clinical interaction;

- Manager rounding on staff and patients;

- Hourly staff rounding on patients;

- Interdisciplinary bedside rounding; and

- Senior leader rounding.

“It is based on best practice tactics that aim to improve the overall patient and family experience,” says Damaris Valera, MS, CMPE, director of the hospital’s Service Excellence Program.

Cogent Healthcare at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla., places a large emphasis on AIDET principles—acknowledge, introduce, duration, explanation, and thank you—during each patient encounter, says Larry Sharp, MD, SFHM, system medical director. AIDET principles entail offering a pleasant greeting and introducing yourself to patients, keeping patients abreast of wait times, explaining procedures, and thanking patients for the opportunity to participate in their care.

The medical director makes shadow rounds with providers and then ghost rounds by surveying the patients after rounds to get the patients’ direct feedback about encounters.

“We provide information to our providers from these rounds as a method to improve care,” Dr. Sharp says.

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago trains hospitalists on communication skills and consequently saw a trend toward improved satisfaction scores and used physician face cards to improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of physicians, which did not impact patient satisfaction, reports Kevin J. O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, associate professor of medicine, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and associate chair for quality in the department of medicine at Northwestern.3,4 Findings were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“These efforts have reinforced the need for multifaceted interventions,” Dr. O’Leary says. “Alone, each one has had little effect, but combined they may have a greater effect. The data is intended to be formative and to identify opportunities to learn.”

Additional improvements have been made due to a better understanding of drivers of low satisfaction.

“Unit medical directors [hospitalists] have started to visit patients to get a qualitative sense of what things affect patient experience,” Dr. O’Leary says. As a result, two previously unidentified issues—ED personnel making promises that can’t be kept to patients and patients receiving conflicting information from specialist consultants and hospitalists—surfaced which could now be addressed.”

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their best efforts to improve the patient experience, hospitalists face myriad obstacles. First, the HCAHPS survey asks about the collective care delivered by doctors during the hospitalization, as opposed to the care given by one particular hospitalist.

“One challenge hospitalists face by not having individual data is not knowing which hospitalists excel at the patient experience and which ones do not,” Dr. Dorrah says. “When no one feels that he or she is the problem, it is difficult to hold individual hospitalists accountable.”

Another problem, Dr. Dorrah reports, stems from the fact that patients may see more than one physician—perhaps several hospitalists or specialists—during their hospitalization. When the HCAHPS survey asks patients to assess the care given by all physicians, patients consider the care given by multiple different physicians.

“Therefore, it is difficult to hold a particular hospitalist accountable for the physician communication domain when he or she is not the only provider influencing patients’ perceptions.”

Some hospital systems still have chosen to attribute HCAHPS doctor communication scores to individual hospitalists. These health systems address the issue by attributing the survey results to the admitting physician, the discharging physician, or all hospitalists who participated in the patient’s care.

“None of these methods are perfect, but health systems are increasingly wanting to ensure their inpatient providers are as invested in the patient experience as their outpatient physicians,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Another obstacle hospitalist groups face is the fact that more attention is given to raising HCAHPS survey scores than to improving the overall patient experience.

“In an effort to raise survey scores, hospitals often lose sight of what truly matters to patients,” Dr. Dorrah says. “Many things contribute to a positive or negative patient experience that are not necessarily measured by the survey. If you only pay attention to the survey, your hospital may overlook things that truly matter to your patients.”

Finally, with the increasing focus on the patient experience, the focus on maintaining a good provider experience can fall short.

“While it’s tempting to ask hospitalists to do more—see more patients, take on more responsibility, and participate in more committees—if hospitals fail to provide a positive environment for their hospitalists, they will have a difficult time fully engaging their hospitalists with the patient experience,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Some situations are out of the hospitalists’ hands. A patient may get upset or angry, and the cause is outside of anyone’s control.

“They may have to spend a night in the emergency department or have an unfavorable outcome,” Dr. Hunter says. “In those instances, employ the art of personal interaction—try to empathize with patients and let them know that you care about them.”

Another limitation, Dr. Sharp says, is that you can’t specifically script encounters to “teach to the test,” by using verbiage with the patient that is verbatim from the satisfaction survey questions.

“Nor can we directly control the temperature in patients’ rooms or the quality of their food,” he says. “We also do not have direct control over a negative experience in the emergency department before patients are referred to us, and many surveys show that it is very difficult to overcome a bad experience.”

Tools at Your Fingertips

As a result of the growing emphasis on patient-centered care, SHM created a Patient Experience Committee this year. SHM defines patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.” The committee is looking at the issues at hand and defining the patient experience and what makes it good.

“We are looking at success stories, as well as not so successful stories, from some of our members to identify what seems to work and what doesn’t work,” says Dr. Sharp, a member of the committee. “By identifying best practices, we can then share this knowledge with the rest of the society, along with methods to implement these practices. We can centralize the gathered knowledge and data and then analyze and make it available to SHM members for their implementation and use.”

The hospitalist plays a key role in the patient experience. Now, more than ever, it’s important to do what you can to make it positive. Consider initiatives you might want to participate in—and perhaps even start your own.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS). CMS.gov. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- Survey of patients’ experiences (HCAHPS). Medicare.gov/Hospital Compare. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- O’Leary KJ, Darling TA, Rauworth J, Williams MV. Impact of hospitalist communication-skills training on patient-satisfaction scores. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):315-320.

- Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospital physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

Special Reports

Hospitalists are often perceived as the face of the hospital, whether that is their official responsibility or not. They are on the front lines of hearing, seeing, and understanding where gaps exist in a patient’s experience.

“Whenever I hear a patient complain, I can almost piece together what happened without having to interview other staff,” says Jairy C. Hunter III, MD, MBA, SFHM, associate CMO for care transitions at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

“Up to this point, there hasn’t been as much accountability regarding customer satisfaction in our industry compared to other industries,” Dr. Hunter says.

The paradigm shift has occurred because payers are demanding it. They want value and satisfaction in what they are paying for. In fact, there is a movement to try to standardize procedures whenever possible, such as the amount of time it takes someone to answer a call bell or the volume of noise in a hallway.

“Patients are being asked questions about such topics in surveys,” Dr. Hunter says. “Although these types of questions don’t involve medical decision-making or a course of treatment, they do include personal interactions that influence how patients feel about their hospital experience.”

Another reason for the shift is the significant increase in the use of electronic communication devices and the explosion of online ratings of consumer products and services. Naturally, consumers want access to accurate and easy-to-use information about the quality of healthcare services.

Patient experience surveys focus on how patients’ experienced or perceived key aspects of their care, not how satisfied they were with their care.1 One way a hospital can measure patient experience is with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, which was developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).2 Although other patient satisfaction/experience vendors offer surveys, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 states that all Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems (IPPS) hospitals who wish to receive their full annual payment update must collect and submit HCAHPS data to CMS.

The HCAHPS survey, which employs standardized survey instrument and data collection methodology to measure patients’ perspectives on hospital care, is administered to a random sample of patients throughout the year. CMS cleans, adjusts, and analyzes the data and then publicly reports the results. All CAHPS products are available at no cost at www.cahps.ahrq.gov.2

Christine Crofton, PhD, director of CAHPS in Rockville, Md., notes that the HCAHPS survey focuses on patient experience measures because they are considered more understandable, unambiguous, actionable, and objective compared to general satisfaction ratings. Although CAHPS surveys do ask respondents to provide overall ratings (e.g. rate the physician on a scale of one to 10), their primary focus is to ask patients to report on their experiences with specific aspects of care in order to provide information that is not biased by different expectations.

For example, if a patient doesn’t understand what symptoms or problems to report to his or her provider after leaving the hospital, the lack of understanding could lead to a complication, a worsening condition, or readmission.

“A specific survey question about written discharge instructions will give hospital administrators more actionable information concerning an increase in readmission rates than a response to a 10-point satisfaction scale,” Dr. Crofton explains.

Efforts to Improve

At medical institutions across the nation, hospitalists and their team members are making conscious efforts to improve the patient experience in light of the growing importance of surveys. Baylor Scott and White Health in Round Rock, Texas, offers a lecture series and provider coaching as part of its continuing education program. The training, says Trina E. Dorrah, MD, MPH, a BSWH hospitalist and physician director for quality improvement, encompasses such topics as:

- Dealing with difficult patient scenarios;

- Patient experience improvement tips;

- Tips to improve providers’ explanations; and

- Tips to improve patients’ understanding.

Dr. Dorrah uses one-on-one shadowing to help providers improve the patient experience.

“I accompany the provider when visiting the patient and observe his or her interactions,” she says. “This enables me to help providers to see what skills they can incorporate to positively impact patient experience.”

Interdisciplinary rounds have also helped to improve the patient experience.

“Patients want to know that their entire healthcare team is focused on them and that they are working together to improve their experience,” Dr. Dorrah says. On weekdays, hospitalists lead interdisciplinary rounds with the rest of the care team, including case management, nursing, and therapy. “We discuss our patients and ensure that we are all on the same page regarding the plan.”

In addition, hospitalists round with nurses each morning. “Everyone benefits,” Dr. Dorrah says. “The patient gets more coordinated care and the nurse is better educated about the plan of care for the day. The number of pages from the nurse to the physician is also reduced because the nurse better understands the care plan.”

BSWH, which uses Press Ganey Associates to administer HCAHPS surveys, considers the scores for the doctor communication domain when establishing a hospitalist team goal for the year.

“If our team reaches the goal, the leadership/administrative team rewards the hospitalist team with a financial bonus,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Lawrence General Hospital, in Lawrence, Mass., which also uses Press Ganey Associates to administer and manage its HCAHPS satisfaction surveys, is working to increase the ability of hospitalists and other caregivers to proactively meet and exceed patients’ needs with its Five-to-Thrive program. The program consists of these five strategies:

- Care-Out-Loud: an initiative that charges every clinical and nonclinical staff member to be present, sensitive, and compassionate to the patient and explain each step of the clinical interaction;

- Manager rounding on staff and patients;

- Hourly staff rounding on patients;

- Interdisciplinary bedside rounding; and

- Senior leader rounding.

“It is based on best practice tactics that aim to improve the overall patient and family experience,” says Damaris Valera, MS, CMPE, director of the hospital’s Service Excellence Program.

Cogent Healthcare at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla., places a large emphasis on AIDET principles—acknowledge, introduce, duration, explanation, and thank you—during each patient encounter, says Larry Sharp, MD, SFHM, system medical director. AIDET principles entail offering a pleasant greeting and introducing yourself to patients, keeping patients abreast of wait times, explaining procedures, and thanking patients for the opportunity to participate in their care.

The medical director makes shadow rounds with providers and then ghost rounds by surveying the patients after rounds to get the patients’ direct feedback about encounters.

“We provide information to our providers from these rounds as a method to improve care,” Dr. Sharp says.

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago trains hospitalists on communication skills and consequently saw a trend toward improved satisfaction scores and used physician face cards to improve patients’ knowledge of the names and roles of physicians, which did not impact patient satisfaction, reports Kevin J. O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, associate professor of medicine, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and associate chair for quality in the department of medicine at Northwestern.3,4 Findings were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“These efforts have reinforced the need for multifaceted interventions,” Dr. O’Leary says. “Alone, each one has had little effect, but combined they may have a greater effect. The data is intended to be formative and to identify opportunities to learn.”

Additional improvements have been made due to a better understanding of drivers of low satisfaction.

“Unit medical directors [hospitalists] have started to visit patients to get a qualitative sense of what things affect patient experience,” Dr. O’Leary says. As a result, two previously unidentified issues—ED personnel making promises that can’t be kept to patients and patients receiving conflicting information from specialist consultants and hospitalists—surfaced which could now be addressed.”

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their best efforts to improve the patient experience, hospitalists face myriad obstacles. First, the HCAHPS survey asks about the collective care delivered by doctors during the hospitalization, as opposed to the care given by one particular hospitalist.

“One challenge hospitalists face by not having individual data is not knowing which hospitalists excel at the patient experience and which ones do not,” Dr. Dorrah says. “When no one feels that he or she is the problem, it is difficult to hold individual hospitalists accountable.”

Another problem, Dr. Dorrah reports, stems from the fact that patients may see more than one physician—perhaps several hospitalists or specialists—during their hospitalization. When the HCAHPS survey asks patients to assess the care given by all physicians, patients consider the care given by multiple different physicians.

“Therefore, it is difficult to hold a particular hospitalist accountable for the physician communication domain when he or she is not the only provider influencing patients’ perceptions.”

Some hospital systems still have chosen to attribute HCAHPS doctor communication scores to individual hospitalists. These health systems address the issue by attributing the survey results to the admitting physician, the discharging physician, or all hospitalists who participated in the patient’s care.

“None of these methods are perfect, but health systems are increasingly wanting to ensure their inpatient providers are as invested in the patient experience as their outpatient physicians,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Another obstacle hospitalist groups face is the fact that more attention is given to raising HCAHPS survey scores than to improving the overall patient experience.

“In an effort to raise survey scores, hospitals often lose sight of what truly matters to patients,” Dr. Dorrah says. “Many things contribute to a positive or negative patient experience that are not necessarily measured by the survey. If you only pay attention to the survey, your hospital may overlook things that truly matter to your patients.”

Finally, with the increasing focus on the patient experience, the focus on maintaining a good provider experience can fall short.

“While it’s tempting to ask hospitalists to do more—see more patients, take on more responsibility, and participate in more committees—if hospitals fail to provide a positive environment for their hospitalists, they will have a difficult time fully engaging their hospitalists with the patient experience,” Dr. Dorrah says.

Some situations are out of the hospitalists’ hands. A patient may get upset or angry, and the cause is outside of anyone’s control.

“They may have to spend a night in the emergency department or have an unfavorable outcome,” Dr. Hunter says. “In those instances, employ the art of personal interaction—try to empathize with patients and let them know that you care about them.”

Another limitation, Dr. Sharp says, is that you can’t specifically script encounters to “teach to the test,” by using verbiage with the patient that is verbatim from the satisfaction survey questions.

“Nor can we directly control the temperature in patients’ rooms or the quality of their food,” he says. “We also do not have direct control over a negative experience in the emergency department before patients are referred to us, and many surveys show that it is very difficult to overcome a bad experience.”

Tools at Your Fingertips

As a result of the growing emphasis on patient-centered care, SHM created a Patient Experience Committee this year. SHM defines patient experience as “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.” The committee is looking at the issues at hand and defining the patient experience and what makes it good.

“We are looking at success stories, as well as not so successful stories, from some of our members to identify what seems to work and what doesn’t work,” says Dr. Sharp, a member of the committee. “By identifying best practices, we can then share this knowledge with the rest of the society, along with methods to implement these practices. We can centralize the gathered knowledge and data and then analyze and make it available to SHM members for their implementation and use.”

The hospitalist plays a key role in the patient experience. Now, more than ever, it’s important to do what you can to make it positive. Consider initiatives you might want to participate in—and perhaps even start your own.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS). CMS.gov. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- Survey of patients’ experiences (HCAHPS). Medicare.gov/Hospital Compare. Accessed August 2, 2015.

- O’Leary KJ, Darling TA, Rauworth J, Williams MV. Impact of hospitalist communication-skills training on patient-satisfaction scores. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):315-320.

- Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss M, Williams MV, O’Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospital physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137-141.

Society of Hospital Medicine Posts Quality Improvement Resources Online

Glycemic Control Webinar

Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation

Presenter: Kristi Kulasa, MD

Date: September 17

Time: 4 p.m. EDT

General QI Webinars

Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics

Presenter: Steve Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM

Date: September 16

Time: 2 p.m. EDT

Other online resources at www.hospitalmedicine.org:

- New FREE clinical topics and guide: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Coming soon: antibiotic stewardship.

- And now, all of SHM’s popular SHMConsults modules are available on the Learning Portal.

With new quality improvement resources available online every month, Hospital Medicine is THE source for hospitalists ready to improve their hospitals.

Glycemic Control Webinar

Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation

Presenter: Kristi Kulasa, MD

Date: September 17

Time: 4 p.m. EDT

General QI Webinars

Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics

Presenter: Steve Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM

Date: September 16

Time: 2 p.m. EDT

Other online resources at www.hospitalmedicine.org:

- New FREE clinical topics and guide: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Coming soon: antibiotic stewardship.

- And now, all of SHM’s popular SHMConsults modules are available on the Learning Portal.

With new quality improvement resources available online every month, Hospital Medicine is THE source for hospitalists ready to improve their hospitals.

Glycemic Control Webinar

Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation

Presenter: Kristi Kulasa, MD

Date: September 17

Time: 4 p.m. EDT

General QI Webinars

Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics

Presenter: Steve Deitelzweig, MD, SFHM

Date: September 16

Time: 2 p.m. EDT

Other online resources at www.hospitalmedicine.org:

- New FREE clinical topics and guide: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- Coming soon: antibiotic stewardship.

- And now, all of SHM’s popular SHMConsults modules are available on the Learning Portal.

With new quality improvement resources available online every month, Hospital Medicine is THE source for hospitalists ready to improve their hospitals.

Inflammation Contributes to Effect of Diabetes on Brain

NEW YORK - Inflammation may contribute to impaired cerebral vasoregulation in type 2 diabetes, research suggests.

In a two-year study, participants with type 2 diabetes experienced diminished regional and global vasoreactivity in the brain, as well as a decline in cognitive function and the ability to perform daily tasks.

Higher blood levels of inflammatory markers were correlated with decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation in the diabetic subjects, but not in controls.

"Normal blood flow regulation allows the brain to redistribute blood to areas of the brain that have increased activity while performing certain tasks," senior author Dr. Vera Novak, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in a news release. "People with type 2 diabetes have impaired blood flow regulation. Our results suggest that diabetes and high blood sugar impose a chronic negative effect on cognitive and decision-making skills."

The study's final analysis involved 40 people, average age 69, including 19 with diabetes and 21 controls. The diabetes patients had been treated for the disease an average of 13 years. Smokers were excluded.

The researchers administered a number of cognition and memory tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and blood tests at the beginning of the study and at 24 months.

At the two-year visit, the diabetics had lower global gray matter volume, lower composite scores on learning and memory, lower regional and global cerebral vasoreactivity, and worse glycemic control, compared to baseline.

Among the diabetics, impaired cerebral vasoreactivity at baseline correlated with worse performance of daily activities. In addition, worsening vasodilation correlated with greater decreases in executive function, independent of age, education, and other factors.

"Higher serum soluble intercellular and vascular adhesion molecules, higher cortisol, and higher C-reactive protein levels at baseline were associated with greater decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation only in the (diabetes) group, independent of diabetes control and 24-hour blood pressure," the researchers wrote online July 8 in Neurology.

"Inflammation may further impair cerebral vasoregulation, which consequently accelerates decline in executive function and daily activities performance in older people with (diabetes)," they said.

"Early detection and monitoring of blood flow regulation may be an important predictor of accelerated changes in cognitive and decision-making skills," Dr. Novak said in the news release. She called for additional studies in a greater number of people and for a longer duration.

"We are currently starting a Phase 2-3 clinical trial to see if intranasal insulin could prevent/slow down cognitive decline," she told Reuters Health by email.

She also noted that while no specific treatment exists to prevent cognitive decline, healthy life styles help people to have less decline.

Large clinical trials have shown that even strict control of blood sugar does not prevent cognitive decline. The high fluctuation in blood glucose that occurs with diabetes damages the nerves of the brain, she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging, American Diabetes Association, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center and National Center for Research Resources.

NEW YORK - Inflammation may contribute to impaired cerebral vasoregulation in type 2 diabetes, research suggests.

In a two-year study, participants with type 2 diabetes experienced diminished regional and global vasoreactivity in the brain, as well as a decline in cognitive function and the ability to perform daily tasks.

Higher blood levels of inflammatory markers were correlated with decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation in the diabetic subjects, but not in controls.

"Normal blood flow regulation allows the brain to redistribute blood to areas of the brain that have increased activity while performing certain tasks," senior author Dr. Vera Novak, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in a news release. "People with type 2 diabetes have impaired blood flow regulation. Our results suggest that diabetes and high blood sugar impose a chronic negative effect on cognitive and decision-making skills."

The study's final analysis involved 40 people, average age 69, including 19 with diabetes and 21 controls. The diabetes patients had been treated for the disease an average of 13 years. Smokers were excluded.

The researchers administered a number of cognition and memory tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and blood tests at the beginning of the study and at 24 months.

At the two-year visit, the diabetics had lower global gray matter volume, lower composite scores on learning and memory, lower regional and global cerebral vasoreactivity, and worse glycemic control, compared to baseline.

Among the diabetics, impaired cerebral vasoreactivity at baseline correlated with worse performance of daily activities. In addition, worsening vasodilation correlated with greater decreases in executive function, independent of age, education, and other factors.

"Higher serum soluble intercellular and vascular adhesion molecules, higher cortisol, and higher C-reactive protein levels at baseline were associated with greater decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation only in the (diabetes) group, independent of diabetes control and 24-hour blood pressure," the researchers wrote online July 8 in Neurology.

"Inflammation may further impair cerebral vasoregulation, which consequently accelerates decline in executive function and daily activities performance in older people with (diabetes)," they said.

"Early detection and monitoring of blood flow regulation may be an important predictor of accelerated changes in cognitive and decision-making skills," Dr. Novak said in the news release. She called for additional studies in a greater number of people and for a longer duration.

"We are currently starting a Phase 2-3 clinical trial to see if intranasal insulin could prevent/slow down cognitive decline," she told Reuters Health by email.

She also noted that while no specific treatment exists to prevent cognitive decline, healthy life styles help people to have less decline.

Large clinical trials have shown that even strict control of blood sugar does not prevent cognitive decline. The high fluctuation in blood glucose that occurs with diabetes damages the nerves of the brain, she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging, American Diabetes Association, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center and National Center for Research Resources.

NEW YORK - Inflammation may contribute to impaired cerebral vasoregulation in type 2 diabetes, research suggests.

In a two-year study, participants with type 2 diabetes experienced diminished regional and global vasoreactivity in the brain, as well as a decline in cognitive function and the ability to perform daily tasks.

Higher blood levels of inflammatory markers were correlated with decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation in the diabetic subjects, but not in controls.

"Normal blood flow regulation allows the brain to redistribute blood to areas of the brain that have increased activity while performing certain tasks," senior author Dr. Vera Novak, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in a news release. "People with type 2 diabetes have impaired blood flow regulation. Our results suggest that diabetes and high blood sugar impose a chronic negative effect on cognitive and decision-making skills."

The study's final analysis involved 40 people, average age 69, including 19 with diabetes and 21 controls. The diabetes patients had been treated for the disease an average of 13 years. Smokers were excluded.

The researchers administered a number of cognition and memory tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and blood tests at the beginning of the study and at 24 months.

At the two-year visit, the diabetics had lower global gray matter volume, lower composite scores on learning and memory, lower regional and global cerebral vasoreactivity, and worse glycemic control, compared to baseline.

Among the diabetics, impaired cerebral vasoreactivity at baseline correlated with worse performance of daily activities. In addition, worsening vasodilation correlated with greater decreases in executive function, independent of age, education, and other factors.

"Higher serum soluble intercellular and vascular adhesion molecules, higher cortisol, and higher C-reactive protein levels at baseline were associated with greater decreases in cerebral vasoreactivity and vasodilation only in the (diabetes) group, independent of diabetes control and 24-hour blood pressure," the researchers wrote online July 8 in Neurology.

"Inflammation may further impair cerebral vasoregulation, which consequently accelerates decline in executive function and daily activities performance in older people with (diabetes)," they said.