User login

Pruritic eruption on the chest

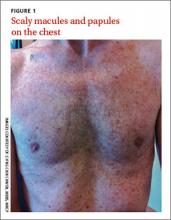

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care for a rash that he’d had on and off for the past 5 years. He’d seen several physicians, but none had been able to make a diagnosis. Topical antifungal creams and steroids provided some improvement, but the rash would always come back.

The patient was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of atopy or skin disease.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Grover’s disease

A clinical diagnosis of Grover’s disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) was confirmed by skin biopsy.

First described in 1970,1 Grover’s disease is characterized by a monomorphic papulovesicular eruption that is limited to the trunk and is seen mainly among middle-aged2 Caucasian men.3 Most cases of Grover’s disease are benign and self-limiting, lasting weeks to months, but it can be difficult to manage and has been reported to be recurrent or persistent.4

Some researchers have proposed that Grover’s disease is caused by obstructed sweat glands that lead to pooled sweat urea coming out of the epidermis, resulting in acantholysis.5 However, patients typically present during the winter months when presumably they perspire less frequently.2

There is some evidence linking infection, infestation, ionizing radiation, drugs such as sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, and recombinant human interleukin-4 with the development of Grover’s disease;3 however, the evidence is weak. Patients with recurrent Grover’s disease often report a history of asteatotic eczema, atopic dermatitis, or contact dermatitis.3

The differential diagnosis includes truncal acne, folliculitis

Because the clinical features of Grover’s disease are often subtle (macules and papules are not florid) and variable (may be red or brown and usually papular but can be acneiform, vesicular, pustular, and even bullous), diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. There are many potential differential diagnoses, including:

Truncal acne may present as inflammatory papules. Patient may complain of itchiness. Comedones and pustules are telltale signs of truncal acne, and are not present in Grover’s disease.

Seborrheic dermatitis often presents as greasy, scaly, eczematous patches, and papules. It can be found on the hair-bearing area on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, postauricular skin, and anterior chest wall. Grover’s disease typically presents on the trunk.

Folliculitis may look very similar to Grover’s disease, and its erythematous papules are often found on the trunk. Distinguishing the 2 can be done on biopsy.

Exanthematous drug eruptions, also called maculopapular eruptions, are not limited to the trunk. They are often associated with the use of a new medication within the previous 4 to 21 days.6

Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis

A diagnosis of Grover’s disease is usually made clinically based on the appearance of the rash and the patient’s age and sex (typically seen in middle-aged men). The diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy. Under a microscope, Grover’s disease has a characteristic appearance of acantholytic dyskeratosis (FIGURE 2); it can be similar in appearance to Darier’s disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, or pemphigus.7

Steroids, other meds are used to reduce itching and inflammation

There are no curative treatments for Grover’s disease. Treatment usually is symptomatic. Local application twice a day of topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide or fluticasone propionate, is often used to relieve the itching and reduce inflammation. Oral steroids, oral retinoids, calcipotriol, phototherapy with ultraviolet B or psoralen plus ultraviolet A light, Grenz radiation, and methotrexate may help clear the eruption in patients with severe itch or extensive or refractory disease.3,8 Antibiotics such as topical fucidin 2 to 3 times a day or oral cloxacillin 500 mg 4 times a day are indicated only if there is secondary impetiginization.

Advise patients to avoid excessive sweating, excessive sun exposure, occlusive clothing, and contact with topical irritants because all of these things are likely to make an outbreak worse.

Our patient was instructed to apply a topical clobetasone butyrate 0.05% cream twice a day. He was also told to take an oral antihistamine, fexofenadine, 180 mg bid for 2 months. The lesions healed, leaving hyperpigmentation. He was advised that the lesions might return in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ch’ng Chin Chwen, MBBS, MRCP, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected]

1.Grover RW. Transient acantholytic dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:426-434.

2. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:263-268.

3. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

4. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, et al. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease). An analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

5. Kato N, Furuya K. Two cases of transient acantholytic dermatosis—with the analysis of 20 cases reported in Japan [in Japanese]. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;101:453-460.

6. Stern RS. Clinical practice. Exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

7. Fernández-Figueras MT, Puig LT, Cannata P, et al. Grover disease: a reappraisal of histopathological diagnostic criteria in 120 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:541-549.

8. Miljkovíc J, Marko PB. Grover’s disease: successful treatment with acitretin and calcipotriol. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116 suppl 2:81-83.

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care for a rash that he’d had on and off for the past 5 years. He’d seen several physicians, but none had been able to make a diagnosis. Topical antifungal creams and steroids provided some improvement, but the rash would always come back.

The patient was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of atopy or skin disease.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Grover’s disease

A clinical diagnosis of Grover’s disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) was confirmed by skin biopsy.

First described in 1970,1 Grover’s disease is characterized by a monomorphic papulovesicular eruption that is limited to the trunk and is seen mainly among middle-aged2 Caucasian men.3 Most cases of Grover’s disease are benign and self-limiting, lasting weeks to months, but it can be difficult to manage and has been reported to be recurrent or persistent.4

Some researchers have proposed that Grover’s disease is caused by obstructed sweat glands that lead to pooled sweat urea coming out of the epidermis, resulting in acantholysis.5 However, patients typically present during the winter months when presumably they perspire less frequently.2

There is some evidence linking infection, infestation, ionizing radiation, drugs such as sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, and recombinant human interleukin-4 with the development of Grover’s disease;3 however, the evidence is weak. Patients with recurrent Grover’s disease often report a history of asteatotic eczema, atopic dermatitis, or contact dermatitis.3

The differential diagnosis includes truncal acne, folliculitis

Because the clinical features of Grover’s disease are often subtle (macules and papules are not florid) and variable (may be red or brown and usually papular but can be acneiform, vesicular, pustular, and even bullous), diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. There are many potential differential diagnoses, including:

Truncal acne may present as inflammatory papules. Patient may complain of itchiness. Comedones and pustules are telltale signs of truncal acne, and are not present in Grover’s disease.

Seborrheic dermatitis often presents as greasy, scaly, eczematous patches, and papules. It can be found on the hair-bearing area on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, postauricular skin, and anterior chest wall. Grover’s disease typically presents on the trunk.

Folliculitis may look very similar to Grover’s disease, and its erythematous papules are often found on the trunk. Distinguishing the 2 can be done on biopsy.

Exanthematous drug eruptions, also called maculopapular eruptions, are not limited to the trunk. They are often associated with the use of a new medication within the previous 4 to 21 days.6

Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis

A diagnosis of Grover’s disease is usually made clinically based on the appearance of the rash and the patient’s age and sex (typically seen in middle-aged men). The diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy. Under a microscope, Grover’s disease has a characteristic appearance of acantholytic dyskeratosis (FIGURE 2); it can be similar in appearance to Darier’s disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, or pemphigus.7

Steroids, other meds are used to reduce itching and inflammation

There are no curative treatments for Grover’s disease. Treatment usually is symptomatic. Local application twice a day of topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide or fluticasone propionate, is often used to relieve the itching and reduce inflammation. Oral steroids, oral retinoids, calcipotriol, phototherapy with ultraviolet B or psoralen plus ultraviolet A light, Grenz radiation, and methotrexate may help clear the eruption in patients with severe itch or extensive or refractory disease.3,8 Antibiotics such as topical fucidin 2 to 3 times a day or oral cloxacillin 500 mg 4 times a day are indicated only if there is secondary impetiginization.

Advise patients to avoid excessive sweating, excessive sun exposure, occlusive clothing, and contact with topical irritants because all of these things are likely to make an outbreak worse.

Our patient was instructed to apply a topical clobetasone butyrate 0.05% cream twice a day. He was also told to take an oral antihistamine, fexofenadine, 180 mg bid for 2 months. The lesions healed, leaving hyperpigmentation. He was advised that the lesions might return in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ch’ng Chin Chwen, MBBS, MRCP, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected]

A 61-year-old Caucasian man sought care for a rash that he’d had on and off for the past 5 years. He’d seen several physicians, but none had been able to make a diagnosis. Topical antifungal creams and steroids provided some improvement, but the rash would always come back.

The patient was otherwise healthy and had no personal or family history of atopy or skin disease.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Grover’s disease

A clinical diagnosis of Grover’s disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) was confirmed by skin biopsy.

First described in 1970,1 Grover’s disease is characterized by a monomorphic papulovesicular eruption that is limited to the trunk and is seen mainly among middle-aged2 Caucasian men.3 Most cases of Grover’s disease are benign and self-limiting, lasting weeks to months, but it can be difficult to manage and has been reported to be recurrent or persistent.4

Some researchers have proposed that Grover’s disease is caused by obstructed sweat glands that lead to pooled sweat urea coming out of the epidermis, resulting in acantholysis.5 However, patients typically present during the winter months when presumably they perspire less frequently.2

There is some evidence linking infection, infestation, ionizing radiation, drugs such as sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, and recombinant human interleukin-4 with the development of Grover’s disease;3 however, the evidence is weak. Patients with recurrent Grover’s disease often report a history of asteatotic eczema, atopic dermatitis, or contact dermatitis.3

The differential diagnosis includes truncal acne, folliculitis

Because the clinical features of Grover’s disease are often subtle (macules and papules are not florid) and variable (may be red or brown and usually papular but can be acneiform, vesicular, pustular, and even bullous), diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. There are many potential differential diagnoses, including:

Truncal acne may present as inflammatory papules. Patient may complain of itchiness. Comedones and pustules are telltale signs of truncal acne, and are not present in Grover’s disease.

Seborrheic dermatitis often presents as greasy, scaly, eczematous patches, and papules. It can be found on the hair-bearing area on the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, postauricular skin, and anterior chest wall. Grover’s disease typically presents on the trunk.

Folliculitis may look very similar to Grover’s disease, and its erythematous papules are often found on the trunk. Distinguishing the 2 can be done on biopsy.

Exanthematous drug eruptions, also called maculopapular eruptions, are not limited to the trunk. They are often associated with the use of a new medication within the previous 4 to 21 days.6

Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis

A diagnosis of Grover’s disease is usually made clinically based on the appearance of the rash and the patient’s age and sex (typically seen in middle-aged men). The diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy. Under a microscope, Grover’s disease has a characteristic appearance of acantholytic dyskeratosis (FIGURE 2); it can be similar in appearance to Darier’s disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, or pemphigus.7

Steroids, other meds are used to reduce itching and inflammation

There are no curative treatments for Grover’s disease. Treatment usually is symptomatic. Local application twice a day of topical steroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide or fluticasone propionate, is often used to relieve the itching and reduce inflammation. Oral steroids, oral retinoids, calcipotriol, phototherapy with ultraviolet B or psoralen plus ultraviolet A light, Grenz radiation, and methotrexate may help clear the eruption in patients with severe itch or extensive or refractory disease.3,8 Antibiotics such as topical fucidin 2 to 3 times a day or oral cloxacillin 500 mg 4 times a day are indicated only if there is secondary impetiginization.

Advise patients to avoid excessive sweating, excessive sun exposure, occlusive clothing, and contact with topical irritants because all of these things are likely to make an outbreak worse.

Our patient was instructed to apply a topical clobetasone butyrate 0.05% cream twice a day. He was also told to take an oral antihistamine, fexofenadine, 180 mg bid for 2 months. The lesions healed, leaving hyperpigmentation. He was advised that the lesions might return in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ch’ng Chin Chwen, MBBS, MRCP, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Lembah Pantai, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected]

1.Grover RW. Transient acantholytic dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:426-434.

2. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:263-268.

3. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

4. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, et al. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease). An analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

5. Kato N, Furuya K. Two cases of transient acantholytic dermatosis—with the analysis of 20 cases reported in Japan [in Japanese]. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;101:453-460.

6. Stern RS. Clinical practice. Exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

7. Fernández-Figueras MT, Puig LT, Cannata P, et al. Grover disease: a reappraisal of histopathological diagnostic criteria in 120 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:541-549.

8. Miljkovíc J, Marko PB. Grover’s disease: successful treatment with acitretin and calcipotriol. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116 suppl 2:81-83.

1.Grover RW. Transient acantholytic dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:426-434.

2. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:263-268.

3. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

4. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, et al. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease). An analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

5. Kato N, Furuya K. Two cases of transient acantholytic dermatosis—with the analysis of 20 cases reported in Japan [in Japanese]. Nihon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi. 1991;101:453-460.

6. Stern RS. Clinical practice. Exanthematous drug eruptions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2492-2501.

7. Fernández-Figueras MT, Puig LT, Cannata P, et al. Grover disease: a reappraisal of histopathological diagnostic criteria in 120 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:541-549.

8. Miljkovíc J, Marko PB. Grover’s disease: successful treatment with acitretin and calcipotriol. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116 suppl 2:81-83.

Abrupt abdominal pain

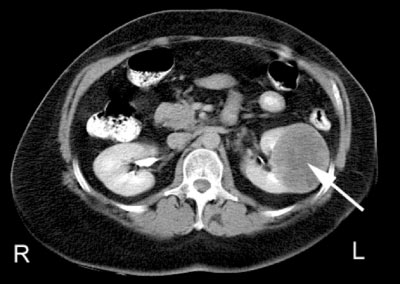

This patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up and was subsequently told that he had duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin. Computed tomography scans revealed inflammation (arrows) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the presence of extraluminal air at the perforation. Fluid was found along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. The perforation was most likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX). The COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins, which play an important role in protecting the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation. Patients at risk for NSAID-related GI complications can benefit from the use of prophylactic agents, such as a proton pump inhibitor.

Suspect a possible perforation in the GI tract in patients who experience sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may initially present as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders. Physical exam findings may include abdominal tenderness and a rigid abdomen, as well as fever and tachycardia.

A patient with a GI tract perforation must first be stabilized to determine if he or she requires surgical intervention (for patients whose perforation results in a persistent air leak) or medical management (for patients whose perforation is healing). In this case, the patient’s duodenal perforation was healing, so he was started on esomeprazole, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole, and was scheduled for an outpatient endoscopy exam.

Adapted from: Singh M, Reichert P, Cann H. Photo Rounds: abrupt onset of abdominal pain. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:749-751.

This patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up and was subsequently told that he had duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin. Computed tomography scans revealed inflammation (arrows) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the presence of extraluminal air at the perforation. Fluid was found along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. The perforation was most likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX). The COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins, which play an important role in protecting the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation. Patients at risk for NSAID-related GI complications can benefit from the use of prophylactic agents, such as a proton pump inhibitor.

Suspect a possible perforation in the GI tract in patients who experience sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may initially present as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders. Physical exam findings may include abdominal tenderness and a rigid abdomen, as well as fever and tachycardia.

A patient with a GI tract perforation must first be stabilized to determine if he or she requires surgical intervention (for patients whose perforation results in a persistent air leak) or medical management (for patients whose perforation is healing). In this case, the patient’s duodenal perforation was healing, so he was started on esomeprazole, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole, and was scheduled for an outpatient endoscopy exam.

Adapted from: Singh M, Reichert P, Cann H. Photo Rounds: abrupt onset of abdominal pain. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:749-751.

This patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up and was subsequently told that he had duodenal perforation caused by indomethacin. Computed tomography scans revealed inflammation (arrows) and thickening of the second and third portion of the duodenum and the presence of extraluminal air at the perforation. Fluid was found along the right paracolic gutter and into the pelvis. The perforation was most likely caused by a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced ulcer.

Gastroduodenal damage is a well-known adverse effect of NSAIDs. NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX). The COX-1 enzyme is responsible for the production of prostaglandins, which play an important role in protecting the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Ulcers in the GI tract can be complicated by perforation. Patients at risk for NSAID-related GI complications can benefit from the use of prophylactic agents, such as a proton pump inhibitor.

Suspect a possible perforation in the GI tract in patients who experience sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that may initially present as epigastric pain and progress to generalized abdominal pain that may radiate to one or both shoulders. Physical exam findings may include abdominal tenderness and a rigid abdomen, as well as fever and tachycardia.

A patient with a GI tract perforation must first be stabilized to determine if he or she requires surgical intervention (for patients whose perforation results in a persistent air leak) or medical management (for patients whose perforation is healing). In this case, the patient’s duodenal perforation was healing, so he was started on esomeprazole, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole, and was scheduled for an outpatient endoscopy exam.

Adapted from: Singh M, Reichert P, Cann H. Photo Rounds: abrupt onset of abdominal pain. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:749-751.

Bumps on breast

The FP explained that these were Montgomery tubercles. These brown papules on and around the areola are caused by hypertrophy of the normal sebaceous glands. She explained to the patient that this is a normal occurrence in some pregnant women and nothing to worry about. She noted that they would likely diminish after the pregnancy was over. The FP emphasized that they would not cause any harm to her or her new baby.

Similar types of sebaceous hyperplasia that may worry patients include Fordyce spots found on the lips and the genitals. These, too, are normal and the principal treatment is reassurance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained that these were Montgomery tubercles. These brown papules on and around the areola are caused by hypertrophy of the normal sebaceous glands. She explained to the patient that this is a normal occurrence in some pregnant women and nothing to worry about. She noted that they would likely diminish after the pregnancy was over. The FP emphasized that they would not cause any harm to her or her new baby.

Similar types of sebaceous hyperplasia that may worry patients include Fordyce spots found on the lips and the genitals. These, too, are normal and the principal treatment is reassurance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP explained that these were Montgomery tubercles. These brown papules on and around the areola are caused by hypertrophy of the normal sebaceous glands. She explained to the patient that this is a normal occurrence in some pregnant women and nothing to worry about. She noted that they would likely diminish after the pregnancy was over. The FP emphasized that they would not cause any harm to her or her new baby.

Similar types of sebaceous hyperplasia that may worry patients include Fordyce spots found on the lips and the genitals. These, too, are normal and the principal treatment is reassurance.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: 462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Itching during pregnancy

The family physician made the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, a condition that is usually diagnosed based on clinical history and presentation. Patients demonstrate pruritus (with or without jaundice) and no primary skin lesions. Laboratory findings consistent with cholestasis (elevated serum bile acid levels and alkaline phosphatase levels) confirm the diagnosis. Elevated bilirubin levels may or may not be found. The etiology remains controversial.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy usually resolves postpartum without specific treatment. It often recurs in subsequent pregnancies and patients have a higher risk of gallstones or a family history of gallstones. It is associated with a higher risk of premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine demise. The pruritus of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy may be treated with oral antihistamines. More severe cases require ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) to relieve the pruritus and improve cholestasis while reducing adverse fetal outcomes.

This patient was treated with oral ursodiol and topical 1% hydrocortisone cream. The bile salts and transaminases were reduced and the patient’s pruritus improved—but did not resolve—until after delivery of a normal healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician made the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, a condition that is usually diagnosed based on clinical history and presentation. Patients demonstrate pruritus (with or without jaundice) and no primary skin lesions. Laboratory findings consistent with cholestasis (elevated serum bile acid levels and alkaline phosphatase levels) confirm the diagnosis. Elevated bilirubin levels may or may not be found. The etiology remains controversial.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy usually resolves postpartum without specific treatment. It often recurs in subsequent pregnancies and patients have a higher risk of gallstones or a family history of gallstones. It is associated with a higher risk of premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine demise. The pruritus of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy may be treated with oral antihistamines. More severe cases require ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) to relieve the pruritus and improve cholestasis while reducing adverse fetal outcomes.

This patient was treated with oral ursodiol and topical 1% hydrocortisone cream. The bile salts and transaminases were reduced and the patient’s pruritus improved—but did not resolve—until after delivery of a normal healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician made the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, a condition that is usually diagnosed based on clinical history and presentation. Patients demonstrate pruritus (with or without jaundice) and no primary skin lesions. Laboratory findings consistent with cholestasis (elevated serum bile acid levels and alkaline phosphatase levels) confirm the diagnosis. Elevated bilirubin levels may or may not be found. The etiology remains controversial.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy usually resolves postpartum without specific treatment. It often recurs in subsequent pregnancies and patients have a higher risk of gallstones or a family history of gallstones. It is associated with a higher risk of premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine demise. The pruritus of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy may be treated with oral antihistamines. More severe cases require ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) to relieve the pruritus and improve cholestasis while reducing adverse fetal outcomes.

This patient was treated with oral ursodiol and topical 1% hydrocortisone cream. The bile salts and transaminases were reduced and the patient’s pruritus improved—but did not resolve—until after delivery of a normal healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Skin findings in pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:462.466.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Dysuria

The patient was referred to Urology and a cystoscopy showed a bladder tumor; complete endoscopic resection confirmed transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

TCC is the most common type of bladder cancer. Risk factors include smoking (odds ratio increased 3- to 4-fold; 50% attributable risk), exposure to pelvic radiation, and chronic infection, including Schistosoma haematobium and genitourinary tuberculosis. Certain occupations have been linked to an increased risk, including those in which workers are exposed to metals (eg, aluminum), paint and solvents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, diesel engine emissions, and aniline dyes.

A metastatic workup for TCC includes a complete blood count, blood chemistry tests (including alkaline phosphatase tests), liver function tests, and a CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the chest and abdomen. A bone scan is indicated in patients with bone pain and/or elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase.

In this case, the patient had a low-grade tumor and no evidence of metastasis. Thus, he was treated with resection alone and close follow-up by Urology.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Bladder cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:448-452.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was referred to Urology and a cystoscopy showed a bladder tumor; complete endoscopic resection confirmed transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

TCC is the most common type of bladder cancer. Risk factors include smoking (odds ratio increased 3- to 4-fold; 50% attributable risk), exposure to pelvic radiation, and chronic infection, including Schistosoma haematobium and genitourinary tuberculosis. Certain occupations have been linked to an increased risk, including those in which workers are exposed to metals (eg, aluminum), paint and solvents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, diesel engine emissions, and aniline dyes.

A metastatic workup for TCC includes a complete blood count, blood chemistry tests (including alkaline phosphatase tests), liver function tests, and a CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the chest and abdomen. A bone scan is indicated in patients with bone pain and/or elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase.

In this case, the patient had a low-grade tumor and no evidence of metastasis. Thus, he was treated with resection alone and close follow-up by Urology.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Bladder cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:448-452.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was referred to Urology and a cystoscopy showed a bladder tumor; complete endoscopic resection confirmed transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).

TCC is the most common type of bladder cancer. Risk factors include smoking (odds ratio increased 3- to 4-fold; 50% attributable risk), exposure to pelvic radiation, and chronic infection, including Schistosoma haematobium and genitourinary tuberculosis. Certain occupations have been linked to an increased risk, including those in which workers are exposed to metals (eg, aluminum), paint and solvents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, diesel engine emissions, and aniline dyes.

A metastatic workup for TCC includes a complete blood count, blood chemistry tests (including alkaline phosphatase tests), liver function tests, and a CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the chest and abdomen. A bone scan is indicated in patients with bone pain and/or elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase.

In this case, the patient had a low-grade tumor and no evidence of metastasis. Thus, he was treated with resection alone and close follow-up by Urology.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Bladder cancer. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:448-452.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Left-sided flank pain

The CT scan revealed a solid left renal mass; a biopsy confirmed renal cell carcinoma (RCC). A subsequent workup for metastatic disease was negative.

Renal tumors are a heterogeneous group of kidney neoplasms derived from the various parts of the nephron. Each type of tumor possesses distinct genetic characteristics, histologic features, and to some extent, clinical phenotypes that range from benign (approximately 20% of small masses) to high-grade malignancy. Up to 95% of kidney neoplasms are RCCs.

For localized disease, partial nephrectomy for small tumors and radical nephrectomy (complete removal of the kidney and Gerota fascia) for large tumors is the gold standard. This patient underwent a radical nephrectomy without complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Renal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:441-447.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan revealed a solid left renal mass; a biopsy confirmed renal cell carcinoma (RCC). A subsequent workup for metastatic disease was negative.

Renal tumors are a heterogeneous group of kidney neoplasms derived from the various parts of the nephron. Each type of tumor possesses distinct genetic characteristics, histologic features, and to some extent, clinical phenotypes that range from benign (approximately 20% of small masses) to high-grade malignancy. Up to 95% of kidney neoplasms are RCCs.

For localized disease, partial nephrectomy for small tumors and radical nephrectomy (complete removal of the kidney and Gerota fascia) for large tumors is the gold standard. This patient underwent a radical nephrectomy without complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Renal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:441-447.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan revealed a solid left renal mass; a biopsy confirmed renal cell carcinoma (RCC). A subsequent workup for metastatic disease was negative.

Renal tumors are a heterogeneous group of kidney neoplasms derived from the various parts of the nephron. Each type of tumor possesses distinct genetic characteristics, histologic features, and to some extent, clinical phenotypes that range from benign (approximately 20% of small masses) to high-grade malignancy. Up to 95% of kidney neoplasms are RCCs.

For localized disease, partial nephrectomy for small tumors and radical nephrectomy (complete removal of the kidney and Gerota fascia) for large tumors is the gold standard. This patient underwent a radical nephrectomy without complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD, and text courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith, M. Renal cell carcinoma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:441-447.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

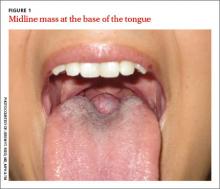

Large mass on base of tongue

A 26-year-old nonsmoking obese woman presented to our primary care clinic for treatment of a mass at the back of her tongue that was causing intermittent dysphagia and nocturnal choking when she was lying down. She had first noticed the mass 3 years ago; it had been asymptomatic until her recent pregnancy, when its size increased significantly. She denied hemoptysis and dyspnea.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lingual thyroid

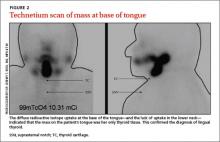

Based on the clinical presentation and location of the mass, and the fact that it had grown larger during pregnancy, we suspected she had lingual thyroid. This is a rare condition that results from the failure of the thyroid to descend from the base of the tongue into the lower neck during early embryogenesis.1 We ordered thyroid function tests and a technetium scan (FIGURE 2), which showed diffuse radioactive isotope uptake at the base of the tongue and no uptake in the lower neck. This indicated that the mass on the tongue was the patient’s only thyroid tissue and thus confirmed the diagnosis.

The incidence of lingual thyroid is 1 in 100,000.2 Women are affected 4 times as often as men, and approximately 75% of patients have no other thyroid tissue.2 Although the condition often is asymptomatic, patients may present with dysphagia, upper airway obstruction, or hemorrhage. Approximately one-third of patients will present with hypothyroidism.3

Differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis for a posterior, midline tongue mass is broad. Midline masses are typically congenital and lateral ones are often malignant, inflammatory, or infectious. Tongue lesions include oral squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), mucoceles, and squamous papillomas.

An SCC of the tongue typically presents as a chronic, nonhealing, irregular mass or ulcer that is hard and bleeds easily with manual palpation. The main causes are constant oral mucosal irritants, usually from smoking, chewing tobacco, or alcohol consumption.4 Firm neck lymphadenopathy is common and signifies local metastasis. Men are affected 2 to 4 times more often than women.5,6 Most patients with SCC are >40 years of age.4

Patients with mucoceles often have a history of oral trauma.7 The rapid appearance of a bluish swelling mass is secondary to salivary gland duct disruption as saliva accumulates in surrounding soft tissues. Mucoceles usually occur in patients <20 years of age and are typically <1 cm in diameter.7 They are most commonly found in the lower lip, yet can occur anywhere in the oral cavity. Most will spontaneously rupture and resolve. Definitive treatment is surgical excision.7

Oral squamous papillomas are the most common benign neoplasms of the oral cavity. They typically appear as solitary pink (nonkeratinized) or white (keratinized) lesions on the ventral surface of the tongue, frenulum, or palate.8 They are common in children and adolescents, but can occur at any age. Most arise spontaneously but they also can be caused by direct contact with infected mucosa.

Making the diagnosis

In addition to history and physical exam, diagnosis of lingual thyroid can be confirmed with a radioactive iodine uptake test or a technetium scan. Biopsy is rarely necessary.

Treatment

Lifelong thyroid suppression therapy is warranted for all patients with lingual thyroid9 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In asymptomatic patients this prevents further growth of the lingual thyroid, which often occurs during times of stress such as illness, pregnancy, or puberty.10 In symptomatic patients, thyroid suppression may lead to glandular atrophy and resolution of symptoms.9 Regression in lingual thyroid size is a very slow process. Surgery is reserved for refractory cases and patients with airway obstruction or bleeding.

Our patient’s thyroid-stimulating hormone was significantly elevated at 9.8 mcIU/mL (normal, 0.34-5.60 mcIU/mL) and technetium scanning showed that the lingual thyroid was her only functioning thyroid tissue. It is likely that pregnancy-related stress and increased demand for thyroid hormone caused excessive thyrotropin production. Her lingual thyroid was unable to produce the increased thyroid hormone needed, which resulted in glandular hypertrophy and obstructive symptoms.

Our patient. After we consulted Endocrinology, we started our patient on levothyroxine 125 mcg/d. Six months later, the mass had shrunk in size and her symptoms had improved. We continue to manage her thyroid suppression and monitor her lingual thyroid size twice a year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy T. Reed, MD, MPH & TM, Department of Otolaryngology, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Fort Hood, TX 76544; [email protected]

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality

patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Gupta M, Motwani G. Lingual thyroid. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E1.

2. Rahbar R, Yoon MJ, Connolly LP, et al. Lingual thyroid in children: a rare clinical entity. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1174-1179.

3. Neinas FW, Gorman CA, Devine KD, et al. Lingual thyroid: Clinical characteristics of 15 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:205-210.

4. Fadoo Z, Naz F, Husen Y, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of tongue in an 11-year-old girl. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e199-201.

5. Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:21-25.

6. Shenoi R, Devrukhkar V, Chaudhuri, et al. Demographic and clinical profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: A retrospective study. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:21-26.

7. Chi AC, Lambert PR 3rd, Richardson MS, et al. Oral mucoceles: a clinicopathologic review of 1,824 cases, including unusual variants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1086-1093.

8. Yeatts D, Bums JC. Common oral mucosal lesions in adults. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:2043-2050.

9. Kansal P, Sakati N, Rifai A, et al. Lingual thyroid. Diagnosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2046-2048.

10. Kalan A, Tariq M. Lingual thyroid gland: clinical evaluation and comprehensive management. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:340-341,345-349.

A 26-year-old nonsmoking obese woman presented to our primary care clinic for treatment of a mass at the back of her tongue that was causing intermittent dysphagia and nocturnal choking when she was lying down. She had first noticed the mass 3 years ago; it had been asymptomatic until her recent pregnancy, when its size increased significantly. She denied hemoptysis and dyspnea.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lingual thyroid

Based on the clinical presentation and location of the mass, and the fact that it had grown larger during pregnancy, we suspected she had lingual thyroid. This is a rare condition that results from the failure of the thyroid to descend from the base of the tongue into the lower neck during early embryogenesis.1 We ordered thyroid function tests and a technetium scan (FIGURE 2), which showed diffuse radioactive isotope uptake at the base of the tongue and no uptake in the lower neck. This indicated that the mass on the tongue was the patient’s only thyroid tissue and thus confirmed the diagnosis.

The incidence of lingual thyroid is 1 in 100,000.2 Women are affected 4 times as often as men, and approximately 75% of patients have no other thyroid tissue.2 Although the condition often is asymptomatic, patients may present with dysphagia, upper airway obstruction, or hemorrhage. Approximately one-third of patients will present with hypothyroidism.3

Differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis for a posterior, midline tongue mass is broad. Midline masses are typically congenital and lateral ones are often malignant, inflammatory, or infectious. Tongue lesions include oral squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), mucoceles, and squamous papillomas.

An SCC of the tongue typically presents as a chronic, nonhealing, irregular mass or ulcer that is hard and bleeds easily with manual palpation. The main causes are constant oral mucosal irritants, usually from smoking, chewing tobacco, or alcohol consumption.4 Firm neck lymphadenopathy is common and signifies local metastasis. Men are affected 2 to 4 times more often than women.5,6 Most patients with SCC are >40 years of age.4

Patients with mucoceles often have a history of oral trauma.7 The rapid appearance of a bluish swelling mass is secondary to salivary gland duct disruption as saliva accumulates in surrounding soft tissues. Mucoceles usually occur in patients <20 years of age and are typically <1 cm in diameter.7 They are most commonly found in the lower lip, yet can occur anywhere in the oral cavity. Most will spontaneously rupture and resolve. Definitive treatment is surgical excision.7

Oral squamous papillomas are the most common benign neoplasms of the oral cavity. They typically appear as solitary pink (nonkeratinized) or white (keratinized) lesions on the ventral surface of the tongue, frenulum, or palate.8 They are common in children and adolescents, but can occur at any age. Most arise spontaneously but they also can be caused by direct contact with infected mucosa.

Making the diagnosis

In addition to history and physical exam, diagnosis of lingual thyroid can be confirmed with a radioactive iodine uptake test or a technetium scan. Biopsy is rarely necessary.

Treatment

Lifelong thyroid suppression therapy is warranted for all patients with lingual thyroid9 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In asymptomatic patients this prevents further growth of the lingual thyroid, which often occurs during times of stress such as illness, pregnancy, or puberty.10 In symptomatic patients, thyroid suppression may lead to glandular atrophy and resolution of symptoms.9 Regression in lingual thyroid size is a very slow process. Surgery is reserved for refractory cases and patients with airway obstruction or bleeding.

Our patient’s thyroid-stimulating hormone was significantly elevated at 9.8 mcIU/mL (normal, 0.34-5.60 mcIU/mL) and technetium scanning showed that the lingual thyroid was her only functioning thyroid tissue. It is likely that pregnancy-related stress and increased demand for thyroid hormone caused excessive thyrotropin production. Her lingual thyroid was unable to produce the increased thyroid hormone needed, which resulted in glandular hypertrophy and obstructive symptoms.

Our patient. After we consulted Endocrinology, we started our patient on levothyroxine 125 mcg/d. Six months later, the mass had shrunk in size and her symptoms had improved. We continue to manage her thyroid suppression and monitor her lingual thyroid size twice a year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy T. Reed, MD, MPH & TM, Department of Otolaryngology, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Fort Hood, TX 76544; [email protected]

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality

patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-year-old nonsmoking obese woman presented to our primary care clinic for treatment of a mass at the back of her tongue that was causing intermittent dysphagia and nocturnal choking when she was lying down. She had first noticed the mass 3 years ago; it had been asymptomatic until her recent pregnancy, when its size increased significantly. She denied hemoptysis and dyspnea.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lingual thyroid

Based on the clinical presentation and location of the mass, and the fact that it had grown larger during pregnancy, we suspected she had lingual thyroid. This is a rare condition that results from the failure of the thyroid to descend from the base of the tongue into the lower neck during early embryogenesis.1 We ordered thyroid function tests and a technetium scan (FIGURE 2), which showed diffuse radioactive isotope uptake at the base of the tongue and no uptake in the lower neck. This indicated that the mass on the tongue was the patient’s only thyroid tissue and thus confirmed the diagnosis.

The incidence of lingual thyroid is 1 in 100,000.2 Women are affected 4 times as often as men, and approximately 75% of patients have no other thyroid tissue.2 Although the condition often is asymptomatic, patients may present with dysphagia, upper airway obstruction, or hemorrhage. Approximately one-third of patients will present with hypothyroidism.3

Differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis for a posterior, midline tongue mass is broad. Midline masses are typically congenital and lateral ones are often malignant, inflammatory, or infectious. Tongue lesions include oral squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), mucoceles, and squamous papillomas.

An SCC of the tongue typically presents as a chronic, nonhealing, irregular mass or ulcer that is hard and bleeds easily with manual palpation. The main causes are constant oral mucosal irritants, usually from smoking, chewing tobacco, or alcohol consumption.4 Firm neck lymphadenopathy is common and signifies local metastasis. Men are affected 2 to 4 times more often than women.5,6 Most patients with SCC are >40 years of age.4

Patients with mucoceles often have a history of oral trauma.7 The rapid appearance of a bluish swelling mass is secondary to salivary gland duct disruption as saliva accumulates in surrounding soft tissues. Mucoceles usually occur in patients <20 years of age and are typically <1 cm in diameter.7 They are most commonly found in the lower lip, yet can occur anywhere in the oral cavity. Most will spontaneously rupture and resolve. Definitive treatment is surgical excision.7

Oral squamous papillomas are the most common benign neoplasms of the oral cavity. They typically appear as solitary pink (nonkeratinized) or white (keratinized) lesions on the ventral surface of the tongue, frenulum, or palate.8 They are common in children and adolescents, but can occur at any age. Most arise spontaneously but they also can be caused by direct contact with infected mucosa.

Making the diagnosis

In addition to history and physical exam, diagnosis of lingual thyroid can be confirmed with a radioactive iodine uptake test or a technetium scan. Biopsy is rarely necessary.

Treatment

Lifelong thyroid suppression therapy is warranted for all patients with lingual thyroid9 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In asymptomatic patients this prevents further growth of the lingual thyroid, which often occurs during times of stress such as illness, pregnancy, or puberty.10 In symptomatic patients, thyroid suppression may lead to glandular atrophy and resolution of symptoms.9 Regression in lingual thyroid size is a very slow process. Surgery is reserved for refractory cases and patients with airway obstruction or bleeding.

Our patient’s thyroid-stimulating hormone was significantly elevated at 9.8 mcIU/mL (normal, 0.34-5.60 mcIU/mL) and technetium scanning showed that the lingual thyroid was her only functioning thyroid tissue. It is likely that pregnancy-related stress and increased demand for thyroid hormone caused excessive thyrotropin production. Her lingual thyroid was unable to produce the increased thyroid hormone needed, which resulted in glandular hypertrophy and obstructive symptoms.

Our patient. After we consulted Endocrinology, we started our patient on levothyroxine 125 mcg/d. Six months later, the mass had shrunk in size and her symptoms had improved. We continue to manage her thyroid suppression and monitor her lingual thyroid size twice a year.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy T. Reed, MD, MPH & TM, Department of Otolaryngology, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, Fort Hood, TX 76544; [email protected]

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality

patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

1. Gupta M, Motwani G. Lingual thyroid. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E1.

2. Rahbar R, Yoon MJ, Connolly LP, et al. Lingual thyroid in children: a rare clinical entity. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1174-1179.

3. Neinas FW, Gorman CA, Devine KD, et al. Lingual thyroid: Clinical characteristics of 15 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:205-210.

4. Fadoo Z, Naz F, Husen Y, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of tongue in an 11-year-old girl. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e199-201.

5. Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:21-25.

6. Shenoi R, Devrukhkar V, Chaudhuri, et al. Demographic and clinical profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: A retrospective study. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:21-26.

7. Chi AC, Lambert PR 3rd, Richardson MS, et al. Oral mucoceles: a clinicopathologic review of 1,824 cases, including unusual variants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1086-1093.

8. Yeatts D, Bums JC. Common oral mucosal lesions in adults. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:2043-2050.

9. Kansal P, Sakati N, Rifai A, et al. Lingual thyroid. Diagnosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2046-2048.

10. Kalan A, Tariq M. Lingual thyroid gland: clinical evaluation and comprehensive management. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:340-341,345-349.

1. Gupta M, Motwani G. Lingual thyroid. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E1.

2. Rahbar R, Yoon MJ, Connolly LP, et al. Lingual thyroid in children: a rare clinical entity. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1174-1179.

3. Neinas FW, Gorman CA, Devine KD, et al. Lingual thyroid: Clinical characteristics of 15 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:205-210.

4. Fadoo Z, Naz F, Husen Y, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of tongue in an 11-year-old girl. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e199-201.

5. Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:21-25.

6. Shenoi R, Devrukhkar V, Chaudhuri, et al. Demographic and clinical profile of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: A retrospective study. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:21-26.

7. Chi AC, Lambert PR 3rd, Richardson MS, et al. Oral mucoceles: a clinicopathologic review of 1,824 cases, including unusual variants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1086-1093.

8. Yeatts D, Bums JC. Common oral mucosal lesions in adults. Am Fam Physician. 1991;44:2043-2050.

9. Kansal P, Sakati N, Rifai A, et al. Lingual thyroid. Diagnosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2046-2048.

10. Kalan A, Tariq M. Lingual thyroid gland: clinical evaluation and comprehensive management. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:340-341,345-349.

Bilateral flank pain

The CT scan showed bilateral polycystic kidneys. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a manifestation of a group of inherited disorders resulting in renal cyst development. In the most common form, autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), extensive epithelial-lined cysts develop in the kidney; in some cases, abnormalities also occur in the liver, pancreas, brain, arterial blood vessels, or a combination of these sites.

The current role of therapy in PKD is to slow the rate of progression of renal disease and minimize symptoms. In clinical trials, neither protein restriction nor tight blood pressure control decreased the decline in glomerular filtration rate. However, in a UK population study, increasing coverage (from 7% to 46% of the population prescribed an antihypertensive agent) showed a trend toward decreasing mortality. Increased intensity of antihypertensive therapy was associated with decreasing mortality in people with ADPKD.

For episodes of gross hematuria, bed rest, analgesics, and hydration are recommended. Blood pressure should be controlled to reduce the risk of associated cardiovascular disease. Treat infection as early as possible. If an infected cyst is suspected, agents that penetrate cysts such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin are used.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Polycystic kidneys. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:436-440.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan showed bilateral polycystic kidneys. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a manifestation of a group of inherited disorders resulting in renal cyst development. In the most common form, autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), extensive epithelial-lined cysts develop in the kidney; in some cases, abnormalities also occur in the liver, pancreas, brain, arterial blood vessels, or a combination of these sites.

The current role of therapy in PKD is to slow the rate of progression of renal disease and minimize symptoms. In clinical trials, neither protein restriction nor tight blood pressure control decreased the decline in glomerular filtration rate. However, in a UK population study, increasing coverage (from 7% to 46% of the population prescribed an antihypertensive agent) showed a trend toward decreasing mortality. Increased intensity of antihypertensive therapy was associated with decreasing mortality in people with ADPKD.

For episodes of gross hematuria, bed rest, analgesics, and hydration are recommended. Blood pressure should be controlled to reduce the risk of associated cardiovascular disease. Treat infection as early as possible. If an infected cyst is suspected, agents that penetrate cysts such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin are used.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Polycystic kidneys. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:436-440.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan showed bilateral polycystic kidneys. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a manifestation of a group of inherited disorders resulting in renal cyst development. In the most common form, autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), extensive epithelial-lined cysts develop in the kidney; in some cases, abnormalities also occur in the liver, pancreas, brain, arterial blood vessels, or a combination of these sites.

The current role of therapy in PKD is to slow the rate of progression of renal disease and minimize symptoms. In clinical trials, neither protein restriction nor tight blood pressure control decreased the decline in glomerular filtration rate. However, in a UK population study, increasing coverage (from 7% to 46% of the population prescribed an antihypertensive agent) showed a trend toward decreasing mortality. Increased intensity of antihypertensive therapy was associated with decreasing mortality in people with ADPKD.

For episodes of gross hematuria, bed rest, analgesics, and hydration are recommended. Blood pressure should be controlled to reduce the risk of associated cardiovascular disease. Treat infection as early as possible. If an infected cyst is suspected, agents that penetrate cysts such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin are used.

Photo courtesy of Michael Freckleton, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Polycystic kidneys. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:436-440.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Lower abdominal pain

The CT scan revealed right-sided hydronephrosis. An irregular mass was also seen at the right ureterovesical junction compressing the bladder. Prostate cancer was suspected and later confirmed on biopsy.

Hydronephrosis refers to distention of the renal calyces and pelvis of one or both kidneys by urine. Hydronephrosis is not a disease but a physical result of urinary blockage that may occur at the level of the kidney, ureters, bladder, or urethra. The condition may be physiologic (eg, occurring in up to 80% of pregnant women) or pathologic. Among acquired causes in adults, pelvic tumors, renal calculi, and urethral stricture predominate. If renal colic is present, a renal stone is likely present (90% in one study). Hydronephrosis is common in pregnancy because of the compression from the enlarging uterus and functional effects of progesterone.

In this case, a urologist advised the patient of the results of the biopsy and recommended a prostatectomy. The procedure was done and the hydronephrosis resolved.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Hydronephrosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:430-435.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan revealed right-sided hydronephrosis. An irregular mass was also seen at the right ureterovesical junction compressing the bladder. Prostate cancer was suspected and later confirmed on biopsy.

Hydronephrosis refers to distention of the renal calyces and pelvis of one or both kidneys by urine. Hydronephrosis is not a disease but a physical result of urinary blockage that may occur at the level of the kidney, ureters, bladder, or urethra. The condition may be physiologic (eg, occurring in up to 80% of pregnant women) or pathologic. Among acquired causes in adults, pelvic tumors, renal calculi, and urethral stricture predominate. If renal colic is present, a renal stone is likely present (90% in one study). Hydronephrosis is common in pregnancy because of the compression from the enlarging uterus and functional effects of progesterone.

In this case, a urologist advised the patient of the results of the biopsy and recommended a prostatectomy. The procedure was done and the hydronephrosis resolved.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Hydronephrosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:430-435.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The CT scan revealed right-sided hydronephrosis. An irregular mass was also seen at the right ureterovesical junction compressing the bladder. Prostate cancer was suspected and later confirmed on biopsy.

Hydronephrosis refers to distention of the renal calyces and pelvis of one or both kidneys by urine. Hydronephrosis is not a disease but a physical result of urinary blockage that may occur at the level of the kidney, ureters, bladder, or urethra. The condition may be physiologic (eg, occurring in up to 80% of pregnant women) or pathologic. Among acquired causes in adults, pelvic tumors, renal calculi, and urethral stricture predominate. If renal colic is present, a renal stone is likely present (90% in one study). Hydronephrosis is common in pregnancy because of the compression from the enlarging uterus and functional effects of progesterone.

In this case, a urologist advised the patient of the results of the biopsy and recommended a prostatectomy. The procedure was done and the hydronephrosis resolved.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M. Hydronephrosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:430-435.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

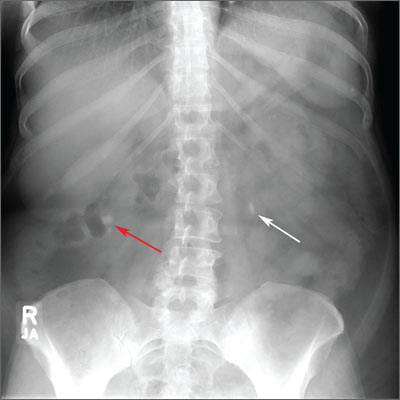

Flank pain

The family physician (FP) noted bilateral renal stones on the abdominal radiograph. A noncontrast CT scan confirmed multiple bilateral renal stones, with an obstructing right distal ureteral stone and enlargement of the right kidney.

A kidney stone is a solid mass that forms when minerals crystallize and collect in the urinary tract. Kidney stones can cause pain and hematuria, and may lead to complications such as urinary tract obstruction and infection.

Stones smaller than 5 mm are likely to pass spontaneously. About three-fourths of distal ureteral stones and about half of proximal ureteral stones will pass spontaneously. Medical expulsive therapy with α-adrenergic blockers (such as tamsulosin) or calcium-channel blockers can increase the chances of stone passage.

Effective pain control should be provided using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotics if needed. NSAIDs may need to be avoided if lithotripsy (see below) is planned because there is an increased risk of perinephric bleeding.

Stones that do not pass spontaneously or with medical expulsive therapy can be treated with lithotripsy or removed via ureteroscopy. Large stones may require percutaneous nephrolithotomy or open surgery.

In this case, the FP recommended adequate fluid intake, which consists of 2 to 3 L of water per day for most patients. The FP also did further work-up (in light of the multiple stones) and determined that the patient had hyperparathyroidism. The FP referred the patient to an endocrinologist for further evaluation and management.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rew K, Smith M. Kidney stones. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:425-429.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician (FP) noted bilateral renal stones on the abdominal radiograph. A noncontrast CT scan confirmed multiple bilateral renal stones, with an obstructing right distal ureteral stone and enlargement of the right kidney.

A kidney stone is a solid mass that forms when minerals crystallize and collect in the urinary tract. Kidney stones can cause pain and hematuria, and may lead to complications such as urinary tract obstruction and infection.

Stones smaller than 5 mm are likely to pass spontaneously. About three-fourths of distal ureteral stones and about half of proximal ureteral stones will pass spontaneously. Medical expulsive therapy with α-adrenergic blockers (such as tamsulosin) or calcium-channel blockers can increase the chances of stone passage.

Effective pain control should be provided using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotics if needed. NSAIDs may need to be avoided if lithotripsy (see below) is planned because there is an increased risk of perinephric bleeding.

Stones that do not pass spontaneously or with medical expulsive therapy can be treated with lithotripsy or removed via ureteroscopy. Large stones may require percutaneous nephrolithotomy or open surgery.

In this case, the FP recommended adequate fluid intake, which consists of 2 to 3 L of water per day for most patients. The FP also did further work-up (in light of the multiple stones) and determined that the patient had hyperparathyroidism. The FP referred the patient to an endocrinologist for further evaluation and management.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rew K, Smith M. Kidney stones. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:425-429.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The family physician (FP) noted bilateral renal stones on the abdominal radiograph. A noncontrast CT scan confirmed multiple bilateral renal stones, with an obstructing right distal ureteral stone and enlargement of the right kidney.

A kidney stone is a solid mass that forms when minerals crystallize and collect in the urinary tract. Kidney stones can cause pain and hematuria, and may lead to complications such as urinary tract obstruction and infection.

Stones smaller than 5 mm are likely to pass spontaneously. About three-fourths of distal ureteral stones and about half of proximal ureteral stones will pass spontaneously. Medical expulsive therapy with α-adrenergic blockers (such as tamsulosin) or calcium-channel blockers can increase the chances of stone passage.

Effective pain control should be provided using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotics if needed. NSAIDs may need to be avoided if lithotripsy (see below) is planned because there is an increased risk of perinephric bleeding.

Stones that do not pass spontaneously or with medical expulsive therapy can be treated with lithotripsy or removed via ureteroscopy. Large stones may require percutaneous nephrolithotomy or open surgery.

In this case, the FP recommended adequate fluid intake, which consists of 2 to 3 L of water per day for most patients. The FP also did further work-up (in light of the multiple stones) and determined that the patient had hyperparathyroidism. The FP referred the patient to an endocrinologist for further evaluation and management.

Photo courtesy of Karl T. Rew, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Rew K, Smith M. Kidney stones. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:425-429.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking this link: http://usatinemedia.com/