User login

NetWorks: Uranium mining, hyperoxia, palliative care education, OSA impact

Health effects of uranium mining

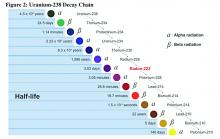

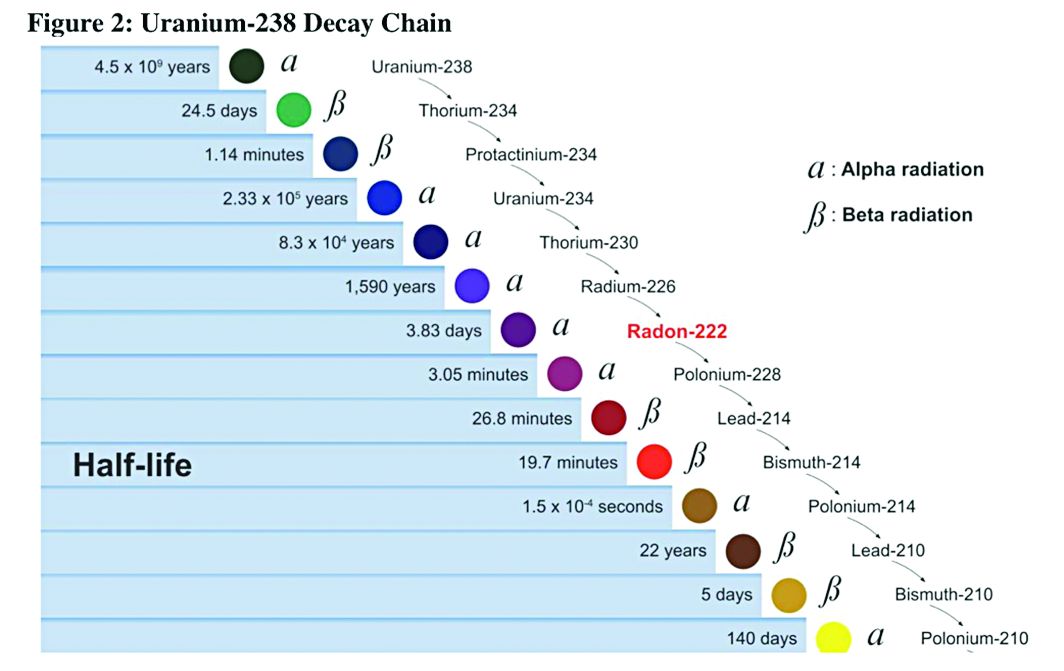

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Health effects of uranium mining

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Health effects of uranium mining

Decay series of U 238

Prior to 1900, uranium was used only for coloring glass. After discovery of radium by Madame Curie in 1898, uranium was widely mined to obtain radium (a decay product of uranium).

While uranium was not directly mined until 1900, uranium contaminates were in the ore in silver and cobalt mines in Czechoslovakia, which were heavily mined in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were no reports (written in English) of lung cancer associated with radiation until 1942; but in 1944, these results were called into question in a monograph from the National Cancer Institute. The carcinogenicity of radon was confirmed in 1951; however, this remained an internal government document until 1980. By 1967, the increased prevalence of lung cancer in uranium miners was widely known. By 1970, new ventilation standards for uranium mines were established.

Lung cancer risk associated with uranium mining is the result of exposure to radon gas and specifically radon progeny of Polonium 218 and 210. These radon progeny remain suspended in air, attached to ambient particles (diesel exhaust, silica) and are then inhaled into the lung, where they tend to precipitate on the major airways. Polonium 218 and 210 are alpha emitters, which have a 20-fold increase in energy compared with gamma rays (the primary radiation source in radiation therapy). Given the mass of alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons), they interact with superficial tissues; thus, once deposited in the large airways, a large radiation dose is directed to the respiratory epithelium of these airways.

Occupational control of exposure to radon and radon progeny is accomplished primarily by ventilation. In high-grade deposits of uranium, such as the 20% ore grades in the Athabasca Basin of Saskatchewan, remote control mining is performed.

Smoking, in combination with occupational exposure to radon progeny, carries a greater than additive but less than multiplicative risk of lung cancer.

In addition to the lung cancer risk associated with radon progeny exposure, uranium miners share the occupational risks of other miners: exposure to silica and diesel exhaust. Miners are also at risk for traumatic injuries, including electrocution.

Health effects associated with uranium milling, enrichment, and tailings will be discussed in a subsequent CHEST Physician article.

Richard B. Evans, MD, MPH, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Hyperoxia in critically ill patients: What’s the verdict?

Oxygen saturation is considered to be the “fifth vital sign,” and current guidelines recommend target oxygen saturation (SpO2) between 94% and 98%, with lower targets for patients at risk for hypercapnic respiratory failure (O’Driscoll BR et al. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl):vi1). Oxygen toxicity is well-demonstrated in experimental animal studies. While its incidence and impact on outcomes is difficult to determine in the clinical setting, increases in-hospital mortality have been associated with hyperoxia in patients with cardiac arrest, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke (Kligannon et al. JAMA. 2010;303[21]:2165; Stub et al. Circulation. 2015;131[24]:2143; Rincon et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[2]:387).

Complementing the findings of Girardis and colleagues, a recent analysis of more than 14,000 critically ill patients, found that time spent at PaO2 > 200 mm Hg was associated with excess mortality and fewer ventilator-free days (Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[2]:187).

While other trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of conservative oxygen therapy in critically ill patients (Panwar et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193[1]:43; Helmerhorst et al. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44[3]:554; Suzuki et al. Crit Care Med. 2014;42[6]:1414), they did not find significant differences between conservative and liberal oxygen therapy with regards to new organ dysfunction or mortality. However, the degree of hyperoxia was usually more modest than in either the Girardis trial or the Helmerhorst (2017) analysis.

Amanpreet Kaur, MD

Steering Committee Fellow-in-Training

David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

Education in palliative medicine

Prompted by concerns that the Affordable Care Act would be instituting “death panels” as part of cost-containment measures, “Dying in America” (a 2015 report of the Institute of Medicine [IOM]) identified compassionate, affordable, and effective care for patients at the end of their lives as a “national priority” in American health care. The IOM identified the education of all primary care providers in the delivery of basic palliative care, specifically commenting that all clinicians who manage patients with serious, life-threatening illnesses should be “competent in basic palliative care” (IOM, The National Academies Press 2015).

Check out our NetWork Storify page later this year for links to the ongoing discussion surrounding palliative care in medicine and for useful tools in the effort to provide palliative care to all our patients.

Laura Johnson, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Vice Chair

The impact of sleep apnea: Why should we care?

With recent large trials such as the SAVE and the SERVE-HF studies challenging the cardiovascular benefits of treating sleep-disordered breathing in specific patient subsets, many physicians may start to question, “Why all the fuss?” The Sleep NetWork is bringing the leaders in the field to CHEST 2017 to discuss their take on where we stand with the connection between sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease, so stay tuned!

Our relationships, general health, and work productivity can be affected by untreated OSA. The effect on daily life may not be initially obvious. Patients often present only at the insistence of their partner or physician, only to be surprised at how much better they feel once treated. Symptoms of OSA are associated with a higher rate of impaired work performance, sick leave, and divorce (Grunstein et al. Sleep. 1995;18[8]:635). A recent survey estimates an $86.9 billion loss of workplace productivity due to sleep apnea in 2015 (Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. AASM; 2016. http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/pdf/sleep-apnea-economic-crisis.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2017.). The same survey found that among those who are employed, treating OSA was associated with a decline in absences by 1.8 days per year and an increase in productivity 17.3% on average. Considering that the majority of OSA remains undiagnosed, this could have tremendous economic impact.

OSA is an important public health burden. The Sleep NetWork is committed to increasing awareness among individuals (patients and clinicians) and institutions (transportation agencies, government) of the impact of sleep-disordered breathing on society.

Aneesa Das, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Chair

In Memoriam

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Sandra K. Willsie, DO, FCCP, died on March 26, 2017, after a courageous battle with brain cancer. As an osteopathic physician with board certification in internal medicine, pulmonary diseases, and critical care medicine, Sandra worked diligently for over 30 years to further scientific discovery and health-care education.

An NIH-funded career academic awardee, a Macy Institute scholar, and an invited faculty member on health-care leadership at Harvard University, Sandra was very involved in academic medicine. She served as professor of medicine, interim chair of medicine and docent at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine; and as provost, dean, vice-dean, and department chair at Kansas City University of Osteopathic Medicine. Sandra earned a master’s degree in bioethics and health policy focusing on research ethics from Loyola University of Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. She made countless scholarly presentations and published regularly.

Sandra made eight pro bono trips to provide physicians in Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic the latest research updates on asthma and COPD research. She was honored to serve as president of Women Executives in Science and Healthcare and as board president of the American Heart Association’s Midwest Affiliate. She had been volunteering for over 30 years at the KC CARE Clinic in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, and was a committee member of the FDA advisory panel on respiratory and anesthesiology devices.

Sandra devoted many years of active participation to the American College of Chest Physicians and will be missed by so many colleagues and friends. She served on the Board of Regents and on the US and Canadian Council of Governors, was a member of numerous committees, including Education, Ethics, Marketing, Nominating, and Chair of the Scientific Presentations and Awards Committee. A staunch supporter of the CHEST Foundation, she was instrumental in its creation and served as a board and committee member. We extend our heartfelt condolences to her husband, Tom, and her family and many friends.

Critical Care Commentary: Sepsis resuscitation in a post-EGDT age

We must admit that we are all imperfect beings and, as such, we are all incorrect from time to time. In order to evolve to proverbial ‘higher planes of enlightenment,’ we must accept our cognitive errors – sometimes as individuals and other times as a collective entity. Within this framework of improvement through critical reflection, evidence-based medicine has been born. In this commentary, the authors address an area of smoldering contention and conflicting evidence—the role of EGDT in managing sepsis. If their call for an individualized approach to therapy is ultimately the ideal strategy, it may vindicate us all by simultaneously proving us all wrong.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP

The approach to sepsis resuscitation is emblematic of the challenges and opportunities of the evolution in this transition. There was no standardized approach to early sepsis resuscitation in the 20th century, and mortality from the disease approached 50% in many studies. This changed in 2001 with the publication of the landmark early-goal-directed therapy (EGDT) trial (Rivers et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345[19]:1368). This single center trial demonstrated a dramatic 16% absolute decrease in mortality secondary to usage of an aggressive protocol for sepsis resuscitation within the first 6 hours after presentation to the ED. In addition to early cultures and antibiotic therapy in patients randomized to both EGDT and “usual care,” EGDT involved a number of mandatory elements, including placing both an arterial catheter and a central venous catheter capable of measuring continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). Patients received crystalloid or colloid until a predetermined central venous pressure was obtained, and if their mean arterial pressure was still below 65 mm Hg, therapy with pressors was initiated. If their ScvO2 was not 70% or greater, patients were transfused until their hematocrit was greater than 30%, and, if this still did not bring their ScvO2 up, patients were started on a regimen of dobutamine. Multiple trials of varying design subsequently demonstrated efficacy in this approach, which was rapidly adopted worldwide in many centers managing patients with sepsis.

However, many questions remained. All patients were managed the same in EGDT, with no capacity to individualize care, regardless of clinical situation (comorbidities, age, origin of sepsis). In addition, it was never clear which specific elements of the EGDT protocol were responsible for its success, as a bundled protocol could potentially simultaneously include beneficial, harmful, and neutral components. Further, many of the elements of EGDT have not been demonstrated to be beneficial in isolation. For example, multiple studies demonstrate that patients not receiving transfusions until their hemoglobin value reaches 7 g/dL is at least as effective as receiving transfusions to a hemoglobin value of 10 g/dL. Also, there is a wealth of data suggesting that central venous pressure is not an accurate surrogate for intravascular volume.

The difference between the original Rivers trial (demonstrating a huge benefit of EGDT) and the three subsequent trials leads (showing no benefit) was striking and leads to the obvious questions of (a) why were the results so disparate and (b) what should we do for our patients moving forward? Perhaps the most obvious difference in the trials is the baseline mortality in the “usual care” groups between the studies. In the original Rivers study, in-hospital mortality was 46.5% for the “usual care” group. For ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe, 60- to 90-day mortality ranged from 18.8% to 29.2% in the “usual care” group. This means either that the patients in the original EGDT trial were significantly sicker or that something fundamental has changed over time. A closer review of the papers reveals it is likely the latter as, in actuality, the “usual care” group in the three NEJM trials looked a lot like the EGDT group in the original trial. Most patients received significant volume resuscitation in these studies prior to enrollment, and the original ScvO2 was 71% in ProCESS (as opposed to 49% in the original Rivers trial). This suggested that increasing awareness of sepsis that occurred during the 15 years between the EGDT trial and the subsequent three trials – likely due to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, as well as other efforts from both advocacy groups as well as medical organizations – led to better sepsis care on patient presentation. In essence, what was “usual care” in the time of the original EGDT study had become inappropriate care in the modern era, and much of what was protocolized in EGDT had been transformed into “usual care,” even if a specific protocol was not being used. In the setting in which “usual care” had dramatically improved, the original EGDT protocol was not helpful if implemented on all comers. One key reason is that many patients simply improved with volume and antibiotics (which had become “usual care”) and did not need additional interventions. Another reason is that some of the interventions in EGDT (blood transfusion, continuous ScvO2 monitoring) are likely not beneficial in the majority of cases.

These studies have led to significant changes in recommendations in sepsis management guidelines. The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines – published after ARISE, ProCESS and ProMISe trials – still recommend antibiotics, cultures, adequate volume resuscitation (without specifying how to do so), targeting an initial mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg, and vasopressors if a patient remains hypotensive despite adequate fluids (Rhodes et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45). However, no recommendations are made regarding mandatory placement of a central venous catheter, measuring central venous pressure, transfusing to higher hemoglobin, etc.

In many ways, the last 15 years of fluid resuscitation in sepsis represents the triumph of evidence-based medicine over opinion-based medicine and the challenges of moving toward precision medicine. When “usual care” was highly variable without a consistent scientific rationale, EGDT markedly improved outcomes – a clear victory of evidence-based medicine that likely saved thousands of lives. However, when EGDT effectively became “usual care,” each individual element of EGDT bundled together failed to further improve outcome. The new evidence suggested that for all comers, EGDT is no better than the new normal, and, thus, newer guidelines do not recommend most of its components.

Moving forward, what is the best way to resuscitate newly identified patients with sepsis? A big fear in eliminating EGDT in its entirety is that practitioners will not have any guidance on how to manage resuscitation in sepsis and so will revert to less rigorous practice patterns. While we acknowledge that concern, we are optimistic that the future will continue to yield decreases in sepsis mortality. Optimally, volume status will be assessed on an individual basis. Rather than resuscitating every patient with a one-size-fits-all parameter that is fairly crude at best and inaccurate at worst (central venous pressure), bedside caregivers should use whatever tools are most appropriate to their individual patient and expertise. This could include bedside ultrasound, stroke volume variation, esophageal Doppler, passive leg raise, etc, depending on the clinical situation. The concept of appropriate volume resuscitation raised in EGDT continues to be 100% valid, but the implementation is now patient-specific and will vary upon available technology, provider skill, and bedside factors that might make one method superior to the other. Similarly, the failure of EGDT to improve survival in the ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe trials does not mean there is never a role for checking venous blood gases and measuring ScvO2. From our point of view, this would be a gross misinterpretation of the trials, as the finding that all elements of EGDT combined fail to benefit all patients with sepsis on arrival should assuredly not be interpreted as none of the elements of EGDT can ever be beneficial in any patients with sepsis. While we can – and should – learn from the data as they pertain to “all comers,” we equally can – and should – look at each individual patient and determine where they align with what is known (and unknown) in the literature and simultaneously attempt to both personalize and optimize their care utilizing our general knowledge of physiology and individual information that is unique to the patient.

In the future, we hope that sepsis resuscitation will be performed in an analogous fashion to cancer therapy. Understanding a patient’s response at the organ level and cellular and subcellular levels will allow us to individualize initial therapy. For instance, an “omics” evaluation of a patient’s immune system may be helpful for guiding treatment. Distinct patterns of gene and protein expression could potentially demonstrate in advance how different patients will respond differently to the same therapy and, in a dynamic manner, determine whether they are responding according to the expected trajectory. Unfortunately, since this is impractical today, the best we can do is to follow recommendations that are applicable to large populations (the Surviving Sepsis bundles) while simultaneously individualizing therapy when no clear data are available. Further, it is critical to assess and reassess the response at the bedside to optimize outcomes. While it is frustrating that no clear guidance can be given on the best way to measure volume status or fluid responsiveness or when there is utility in measuring ScvO2, there is comfort in knowing that best practice has evolved over the past 15 years such that the majority of EGDT is now “usual care.” Moving forward, the challenges in transitioning sepsis resuscitation from population-based evidence-based medicine to individualized therapy are real, but the opportunities for improved outcomes in this deadly disease are enormous.

Dr. Head is with the Department of Anesthesiology, and Dr. Coopersmith is with the Department of Surgery, Emory Critical Care Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

We must admit that we are all imperfect beings and, as such, we are all incorrect from time to time. In order to evolve to proverbial ‘higher planes of enlightenment,’ we must accept our cognitive errors – sometimes as individuals and other times as a collective entity. Within this framework of improvement through critical reflection, evidence-based medicine has been born. In this commentary, the authors address an area of smoldering contention and conflicting evidence—the role of EGDT in managing sepsis. If their call for an individualized approach to therapy is ultimately the ideal strategy, it may vindicate us all by simultaneously proving us all wrong.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP

The approach to sepsis resuscitation is emblematic of the challenges and opportunities of the evolution in this transition. There was no standardized approach to early sepsis resuscitation in the 20th century, and mortality from the disease approached 50% in many studies. This changed in 2001 with the publication of the landmark early-goal-directed therapy (EGDT) trial (Rivers et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345[19]:1368). This single center trial demonstrated a dramatic 16% absolute decrease in mortality secondary to usage of an aggressive protocol for sepsis resuscitation within the first 6 hours after presentation to the ED. In addition to early cultures and antibiotic therapy in patients randomized to both EGDT and “usual care,” EGDT involved a number of mandatory elements, including placing both an arterial catheter and a central venous catheter capable of measuring continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). Patients received crystalloid or colloid until a predetermined central venous pressure was obtained, and if their mean arterial pressure was still below 65 mm Hg, therapy with pressors was initiated. If their ScvO2 was not 70% or greater, patients were transfused until their hematocrit was greater than 30%, and, if this still did not bring their ScvO2 up, patients were started on a regimen of dobutamine. Multiple trials of varying design subsequently demonstrated efficacy in this approach, which was rapidly adopted worldwide in many centers managing patients with sepsis.

However, many questions remained. All patients were managed the same in EGDT, with no capacity to individualize care, regardless of clinical situation (comorbidities, age, origin of sepsis). In addition, it was never clear which specific elements of the EGDT protocol were responsible for its success, as a bundled protocol could potentially simultaneously include beneficial, harmful, and neutral components. Further, many of the elements of EGDT have not been demonstrated to be beneficial in isolation. For example, multiple studies demonstrate that patients not receiving transfusions until their hemoglobin value reaches 7 g/dL is at least as effective as receiving transfusions to a hemoglobin value of 10 g/dL. Also, there is a wealth of data suggesting that central venous pressure is not an accurate surrogate for intravascular volume.

The difference between the original Rivers trial (demonstrating a huge benefit of EGDT) and the three subsequent trials leads (showing no benefit) was striking and leads to the obvious questions of (a) why were the results so disparate and (b) what should we do for our patients moving forward? Perhaps the most obvious difference in the trials is the baseline mortality in the “usual care” groups between the studies. In the original Rivers study, in-hospital mortality was 46.5% for the “usual care” group. For ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe, 60- to 90-day mortality ranged from 18.8% to 29.2% in the “usual care” group. This means either that the patients in the original EGDT trial were significantly sicker or that something fundamental has changed over time. A closer review of the papers reveals it is likely the latter as, in actuality, the “usual care” group in the three NEJM trials looked a lot like the EGDT group in the original trial. Most patients received significant volume resuscitation in these studies prior to enrollment, and the original ScvO2 was 71% in ProCESS (as opposed to 49% in the original Rivers trial). This suggested that increasing awareness of sepsis that occurred during the 15 years between the EGDT trial and the subsequent three trials – likely due to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, as well as other efforts from both advocacy groups as well as medical organizations – led to better sepsis care on patient presentation. In essence, what was “usual care” in the time of the original EGDT study had become inappropriate care in the modern era, and much of what was protocolized in EGDT had been transformed into “usual care,” even if a specific protocol was not being used. In the setting in which “usual care” had dramatically improved, the original EGDT protocol was not helpful if implemented on all comers. One key reason is that many patients simply improved with volume and antibiotics (which had become “usual care”) and did not need additional interventions. Another reason is that some of the interventions in EGDT (blood transfusion, continuous ScvO2 monitoring) are likely not beneficial in the majority of cases.

These studies have led to significant changes in recommendations in sepsis management guidelines. The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines – published after ARISE, ProCESS and ProMISe trials – still recommend antibiotics, cultures, adequate volume resuscitation (without specifying how to do so), targeting an initial mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg, and vasopressors if a patient remains hypotensive despite adequate fluids (Rhodes et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45). However, no recommendations are made regarding mandatory placement of a central venous catheter, measuring central venous pressure, transfusing to higher hemoglobin, etc.

In many ways, the last 15 years of fluid resuscitation in sepsis represents the triumph of evidence-based medicine over opinion-based medicine and the challenges of moving toward precision medicine. When “usual care” was highly variable without a consistent scientific rationale, EGDT markedly improved outcomes – a clear victory of evidence-based medicine that likely saved thousands of lives. However, when EGDT effectively became “usual care,” each individual element of EGDT bundled together failed to further improve outcome. The new evidence suggested that for all comers, EGDT is no better than the new normal, and, thus, newer guidelines do not recommend most of its components.

Moving forward, what is the best way to resuscitate newly identified patients with sepsis? A big fear in eliminating EGDT in its entirety is that practitioners will not have any guidance on how to manage resuscitation in sepsis and so will revert to less rigorous practice patterns. While we acknowledge that concern, we are optimistic that the future will continue to yield decreases in sepsis mortality. Optimally, volume status will be assessed on an individual basis. Rather than resuscitating every patient with a one-size-fits-all parameter that is fairly crude at best and inaccurate at worst (central venous pressure), bedside caregivers should use whatever tools are most appropriate to their individual patient and expertise. This could include bedside ultrasound, stroke volume variation, esophageal Doppler, passive leg raise, etc, depending on the clinical situation. The concept of appropriate volume resuscitation raised in EGDT continues to be 100% valid, but the implementation is now patient-specific and will vary upon available technology, provider skill, and bedside factors that might make one method superior to the other. Similarly, the failure of EGDT to improve survival in the ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe trials does not mean there is never a role for checking venous blood gases and measuring ScvO2. From our point of view, this would be a gross misinterpretation of the trials, as the finding that all elements of EGDT combined fail to benefit all patients with sepsis on arrival should assuredly not be interpreted as none of the elements of EGDT can ever be beneficial in any patients with sepsis. While we can – and should – learn from the data as they pertain to “all comers,” we equally can – and should – look at each individual patient and determine where they align with what is known (and unknown) in the literature and simultaneously attempt to both personalize and optimize their care utilizing our general knowledge of physiology and individual information that is unique to the patient.

In the future, we hope that sepsis resuscitation will be performed in an analogous fashion to cancer therapy. Understanding a patient’s response at the organ level and cellular and subcellular levels will allow us to individualize initial therapy. For instance, an “omics” evaluation of a patient’s immune system may be helpful for guiding treatment. Distinct patterns of gene and protein expression could potentially demonstrate in advance how different patients will respond differently to the same therapy and, in a dynamic manner, determine whether they are responding according to the expected trajectory. Unfortunately, since this is impractical today, the best we can do is to follow recommendations that are applicable to large populations (the Surviving Sepsis bundles) while simultaneously individualizing therapy when no clear data are available. Further, it is critical to assess and reassess the response at the bedside to optimize outcomes. While it is frustrating that no clear guidance can be given on the best way to measure volume status or fluid responsiveness or when there is utility in measuring ScvO2, there is comfort in knowing that best practice has evolved over the past 15 years such that the majority of EGDT is now “usual care.” Moving forward, the challenges in transitioning sepsis resuscitation from population-based evidence-based medicine to individualized therapy are real, but the opportunities for improved outcomes in this deadly disease are enormous.

Dr. Head is with the Department of Anesthesiology, and Dr. Coopersmith is with the Department of Surgery, Emory Critical Care Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

We must admit that we are all imperfect beings and, as such, we are all incorrect from time to time. In order to evolve to proverbial ‘higher planes of enlightenment,’ we must accept our cognitive errors – sometimes as individuals and other times as a collective entity. Within this framework of improvement through critical reflection, evidence-based medicine has been born. In this commentary, the authors address an area of smoldering contention and conflicting evidence—the role of EGDT in managing sepsis. If their call for an individualized approach to therapy is ultimately the ideal strategy, it may vindicate us all by simultaneously proving us all wrong.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP

The approach to sepsis resuscitation is emblematic of the challenges and opportunities of the evolution in this transition. There was no standardized approach to early sepsis resuscitation in the 20th century, and mortality from the disease approached 50% in many studies. This changed in 2001 with the publication of the landmark early-goal-directed therapy (EGDT) trial (Rivers et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;345[19]:1368). This single center trial demonstrated a dramatic 16% absolute decrease in mortality secondary to usage of an aggressive protocol for sepsis resuscitation within the first 6 hours after presentation to the ED. In addition to early cultures and antibiotic therapy in patients randomized to both EGDT and “usual care,” EGDT involved a number of mandatory elements, including placing both an arterial catheter and a central venous catheter capable of measuring continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). Patients received crystalloid or colloid until a predetermined central venous pressure was obtained, and if their mean arterial pressure was still below 65 mm Hg, therapy with pressors was initiated. If their ScvO2 was not 70% or greater, patients were transfused until their hematocrit was greater than 30%, and, if this still did not bring their ScvO2 up, patients were started on a regimen of dobutamine. Multiple trials of varying design subsequently demonstrated efficacy in this approach, which was rapidly adopted worldwide in many centers managing patients with sepsis.

However, many questions remained. All patients were managed the same in EGDT, with no capacity to individualize care, regardless of clinical situation (comorbidities, age, origin of sepsis). In addition, it was never clear which specific elements of the EGDT protocol were responsible for its success, as a bundled protocol could potentially simultaneously include beneficial, harmful, and neutral components. Further, many of the elements of EGDT have not been demonstrated to be beneficial in isolation. For example, multiple studies demonstrate that patients not receiving transfusions until their hemoglobin value reaches 7 g/dL is at least as effective as receiving transfusions to a hemoglobin value of 10 g/dL. Also, there is a wealth of data suggesting that central venous pressure is not an accurate surrogate for intravascular volume.

The difference between the original Rivers trial (demonstrating a huge benefit of EGDT) and the three subsequent trials leads (showing no benefit) was striking and leads to the obvious questions of (a) why were the results so disparate and (b) what should we do for our patients moving forward? Perhaps the most obvious difference in the trials is the baseline mortality in the “usual care” groups between the studies. In the original Rivers study, in-hospital mortality was 46.5% for the “usual care” group. For ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe, 60- to 90-day mortality ranged from 18.8% to 29.2% in the “usual care” group. This means either that the patients in the original EGDT trial were significantly sicker or that something fundamental has changed over time. A closer review of the papers reveals it is likely the latter as, in actuality, the “usual care” group in the three NEJM trials looked a lot like the EGDT group in the original trial. Most patients received significant volume resuscitation in these studies prior to enrollment, and the original ScvO2 was 71% in ProCESS (as opposed to 49% in the original Rivers trial). This suggested that increasing awareness of sepsis that occurred during the 15 years between the EGDT trial and the subsequent three trials – likely due to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, as well as other efforts from both advocacy groups as well as medical organizations – led to better sepsis care on patient presentation. In essence, what was “usual care” in the time of the original EGDT study had become inappropriate care in the modern era, and much of what was protocolized in EGDT had been transformed into “usual care,” even if a specific protocol was not being used. In the setting in which “usual care” had dramatically improved, the original EGDT protocol was not helpful if implemented on all comers. One key reason is that many patients simply improved with volume and antibiotics (which had become “usual care”) and did not need additional interventions. Another reason is that some of the interventions in EGDT (blood transfusion, continuous ScvO2 monitoring) are likely not beneficial in the majority of cases.

These studies have led to significant changes in recommendations in sepsis management guidelines. The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines – published after ARISE, ProCESS and ProMISe trials – still recommend antibiotics, cultures, adequate volume resuscitation (without specifying how to do so), targeting an initial mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg, and vasopressors if a patient remains hypotensive despite adequate fluids (Rhodes et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45). However, no recommendations are made regarding mandatory placement of a central venous catheter, measuring central venous pressure, transfusing to higher hemoglobin, etc.

In many ways, the last 15 years of fluid resuscitation in sepsis represents the triumph of evidence-based medicine over opinion-based medicine and the challenges of moving toward precision medicine. When “usual care” was highly variable without a consistent scientific rationale, EGDT markedly improved outcomes – a clear victory of evidence-based medicine that likely saved thousands of lives. However, when EGDT effectively became “usual care,” each individual element of EGDT bundled together failed to further improve outcome. The new evidence suggested that for all comers, EGDT is no better than the new normal, and, thus, newer guidelines do not recommend most of its components.

Moving forward, what is the best way to resuscitate newly identified patients with sepsis? A big fear in eliminating EGDT in its entirety is that practitioners will not have any guidance on how to manage resuscitation in sepsis and so will revert to less rigorous practice patterns. While we acknowledge that concern, we are optimistic that the future will continue to yield decreases in sepsis mortality. Optimally, volume status will be assessed on an individual basis. Rather than resuscitating every patient with a one-size-fits-all parameter that is fairly crude at best and inaccurate at worst (central venous pressure), bedside caregivers should use whatever tools are most appropriate to their individual patient and expertise. This could include bedside ultrasound, stroke volume variation, esophageal Doppler, passive leg raise, etc, depending on the clinical situation. The concept of appropriate volume resuscitation raised in EGDT continues to be 100% valid, but the implementation is now patient-specific and will vary upon available technology, provider skill, and bedside factors that might make one method superior to the other. Similarly, the failure of EGDT to improve survival in the ARISE, ProCESS, and ProMISe trials does not mean there is never a role for checking venous blood gases and measuring ScvO2. From our point of view, this would be a gross misinterpretation of the trials, as the finding that all elements of EGDT combined fail to benefit all patients with sepsis on arrival should assuredly not be interpreted as none of the elements of EGDT can ever be beneficial in any patients with sepsis. While we can – and should – learn from the data as they pertain to “all comers,” we equally can – and should – look at each individual patient and determine where they align with what is known (and unknown) in the literature and simultaneously attempt to both personalize and optimize their care utilizing our general knowledge of physiology and individual information that is unique to the patient.

In the future, we hope that sepsis resuscitation will be performed in an analogous fashion to cancer therapy. Understanding a patient’s response at the organ level and cellular and subcellular levels will allow us to individualize initial therapy. For instance, an “omics” evaluation of a patient’s immune system may be helpful for guiding treatment. Distinct patterns of gene and protein expression could potentially demonstrate in advance how different patients will respond differently to the same therapy and, in a dynamic manner, determine whether they are responding according to the expected trajectory. Unfortunately, since this is impractical today, the best we can do is to follow recommendations that are applicable to large populations (the Surviving Sepsis bundles) while simultaneously individualizing therapy when no clear data are available. Further, it is critical to assess and reassess the response at the bedside to optimize outcomes. While it is frustrating that no clear guidance can be given on the best way to measure volume status or fluid responsiveness or when there is utility in measuring ScvO2, there is comfort in knowing that best practice has evolved over the past 15 years such that the majority of EGDT is now “usual care.” Moving forward, the challenges in transitioning sepsis resuscitation from population-based evidence-based medicine to individualized therapy are real, but the opportunities for improved outcomes in this deadly disease are enormous.

Dr. Head is with the Department of Anesthesiology, and Dr. Coopersmith is with the Department of Surgery, Emory Critical Care Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2015 threatens growth of pulmonary rehab

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

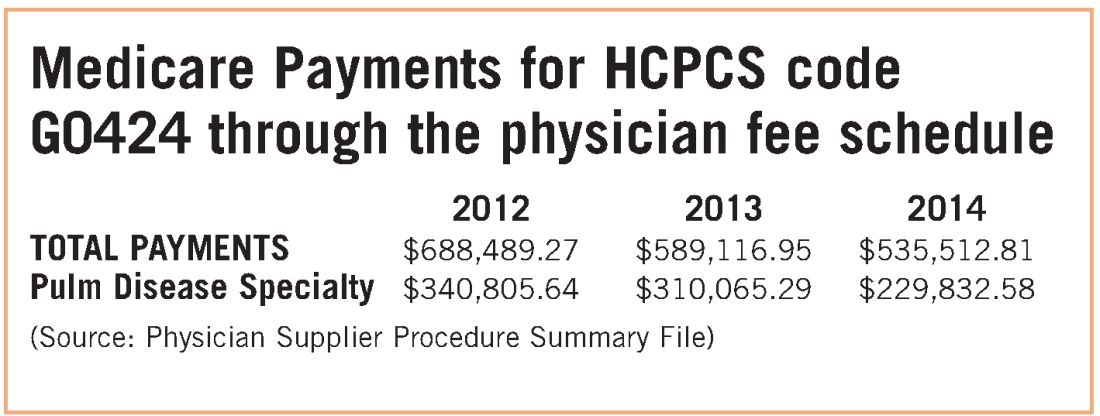

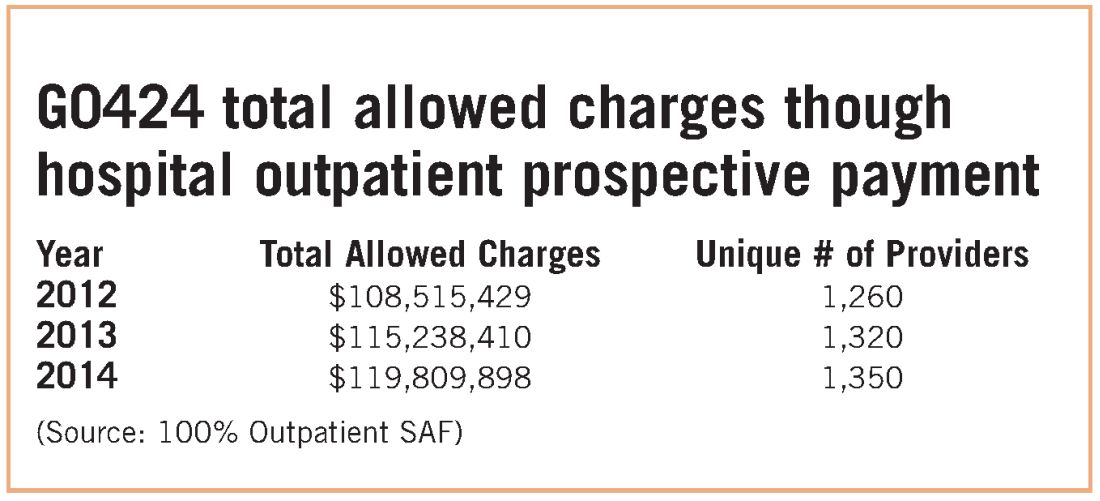

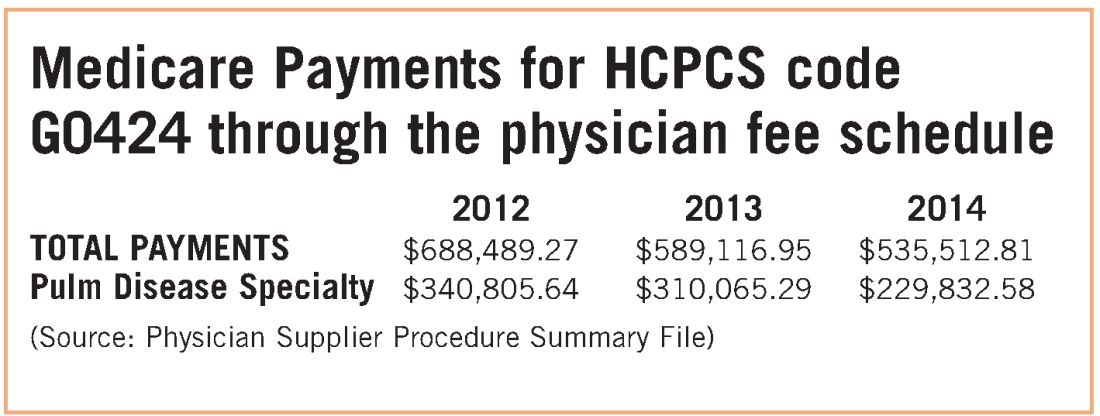

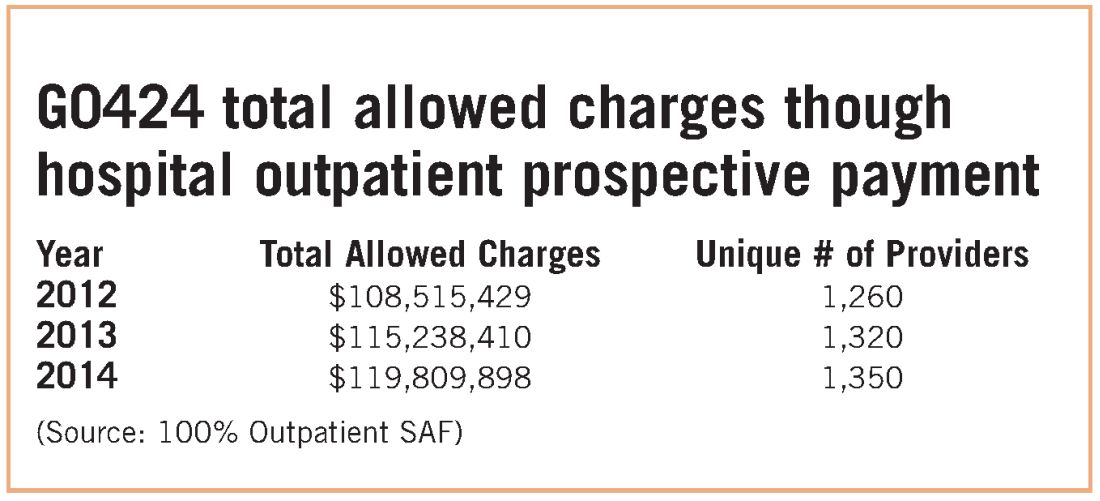

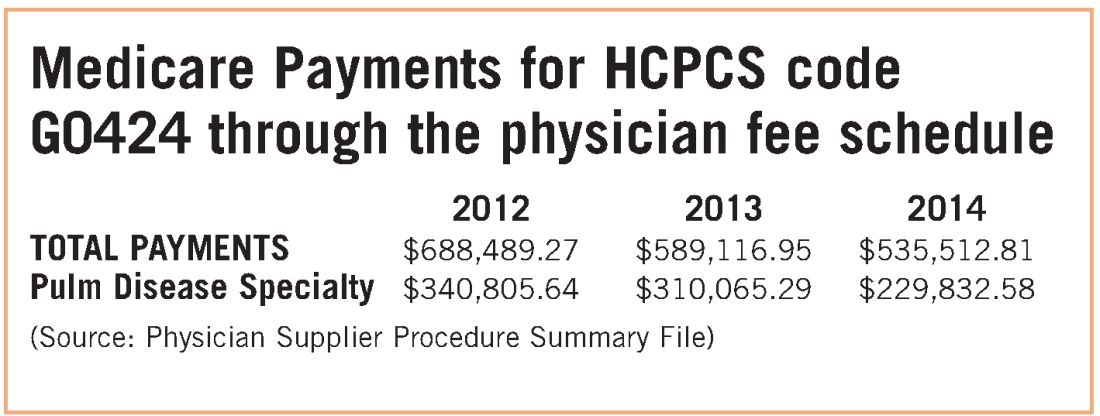

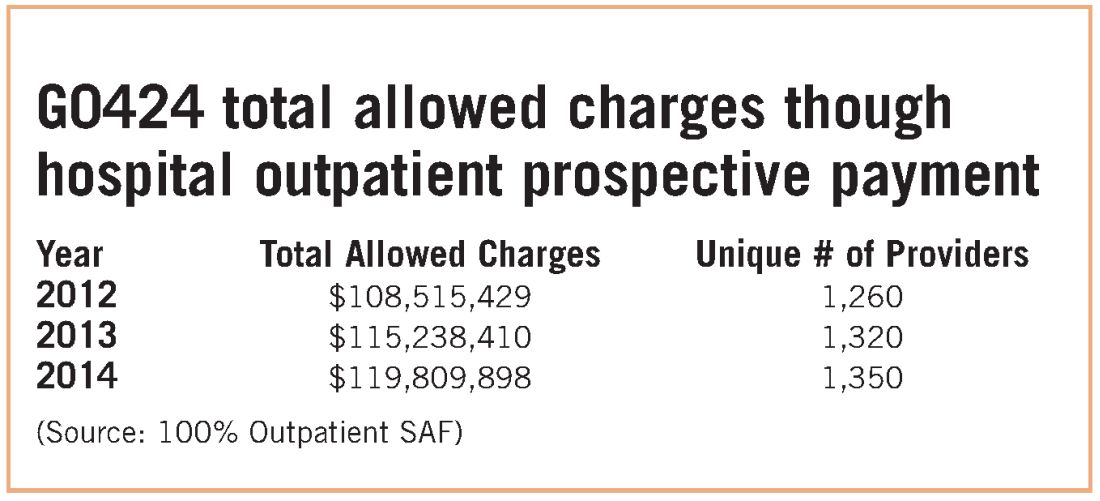

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

In late 2015, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) to address numerous wide-ranging budget concerns, including issues related to agriculture, pensions, the strategic petroleum reserve, along with some Medicare issues. Section 603 of BBA is now coming back to haunt pulmonary rehabilitation services.

The intent of Section 603 is reasonable – to address the phenomenon of hospitals purchasing physician practices to take advantage of payment differentials between identical or virtually identical services when comparing the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (HOPPS) and the physician fee schedule (PFS). For example, an orthopedic practice might own its own MRI and related support services. It will bill for those services under the PFS. However, if the practice sells that segment of the revenue stream (the MRI assets, etc) to a hospital, the hospital can bill Medicare for those same services under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system at an amount notably higher than the PFS payment.

To address this payment aberration, Congress instructed the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to craft a system to preclude a hospital from such behavior. If a hospital offers new or expanded outpatient services, it could NOT bill Medicare under the hospital outpatient services methodology and would be required to bill under the PFS payment methodology. Importantly, a few exemptions exist. If the new or expanded service is within 250 yards of the main hospital campus, the outpatient billing methodology is permitted. Likewise, if expansion of a current off-campus service occurs at the same location of the current off-site service, the hospital may continue to bill under the outpatient rules. Several other technical exceptions are permitted, for example construction planned prior to passage of BBA.

The implications for pulmonary rehabilitation are critical to its growth. A hospital that wishes to expand its current program and bill under the hospital outpatient methodology MUST do so by expanding at its current location. An expansion at a new location that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus triggers Section 603 provisions, and the hospital will bill at the physician fee schedule rate. Because the PFS payment rate is just over half of the payment rate for HOPPS payment, it is unlikely that a hospital would expand an existing program or establish a new one if it would be forced to bill under the lower rate.

While congressional logic may be relatively understandable, for pulmonary medicine, it is based on the premise that a hospital would purchase a pulmonary practice because that practice had a lucrative pulmonary rehabilitation services cash flow. NAMDRC and other societies were able to document major flaws in the basic premise, resulting in very problematic unintended consequences. A detailed review of Medicare claims data provides strong evidence that pulmonary practices simply do not provide pulmonary rehab services.

These data strongly indicate that G0424 pulmonary practice physician office billing for the most recent year data are available ($230K), compared with hospital outpatient allowed charges ($119M), is less than two-tenths of 1% of billing through the hospital setting. To argue that hospitals are purchasing pulmonary practices for financial gain tied to pulmonary rehab services defies Medicare data, as well as financial logic. If the CMS premise was valid, one would expect the aggregate physician office billing to be much greater than $535K. In discussions with CMS, the Agency did agree that there are likely to be unintended consequences related to Section 603 implementation. The Agency also emphasizes that it does not have the statutory authority for a “carve out” exemption. CMS stated that even if it agreed with us, it simply lacked the authority to exempt pulmonary rehab services. CMS also agreed that there is growing evidence that pulmonary rehab is a underutilized service that may very well save the program money through reduced hospitalizations and rehospitalizations, but it has little choice to implement the statute as Congress so mandated.

Therefore, the only solution is a legislative one. NAMDRC and other societies are seriously considering approaching Congress for such resolution.

Registration is now open for CHEST Board Review 2017

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

Looking for in-person board review prep? Join us in Orlando, August 18 to 27, for the best live review of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine.

Register by March 31 and save $100. Registration can be done at http://boardreview.chestnet.org.

NetWorks: Mass shootings, MACRA, asthma in pregnancy Disaster Response Practice Operations Transplant Women’s Health

Mass shootings

There are multiple definitions for a mass shooting. Some definitions require a certain number of people be killed. Some definitions require a certain number of people be shot. Some definitions do not include gang violence. Regardless of the definition used, the number of mass shootings in the United States is increasing.

There are also multiple definitions of what qualifies as a medical disaster. These definitions can be summarized with the statement that a medical disaster is an event that produces a number of casualties that overwhelms the local health system.

Most mass shootings fit the definition of a medical disaster. When a mass shooting occurs, medical resources are diverted from current patients to those injured in the shooting. Patients with acute medical problems unrelated to the shooting must endure a prolonged wait for medical care.

The CHEST Disaster Response NetWork feels that it is necessary to take action to reduce the number of mass shootings. Unlike natural disasters, mass shootings are man-made. As such, we should proactively work to prevent them. Prevention is a large part of medicine. Working together with community leaders, law enforcement, and government officials, we can and should work to eliminate mass shootings so that we can minimize gun-related injury and death.

MACRA: Reincarnation of Medicare physician reimbursement model

In April 2015, President Obama signed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) eradicating the detested sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. If this is your first dive into MACRA as an eligible professional (EP), it may be a bit baffling trying to understand its impact on your practice.

Under MIPS, rules are divided into four categories. During the first year, each category will make up a certain percentage to the physician’s overall score, which will result in a penalty or payment as a lump sum in 2019. If you are an Advanced APM in 2017 and receive 25% of Medicare payments or see 20% of your Medicare patients through this model, you can earn up to a 5% incentive payment in 2019.

The performance period started on January 1, 2017. Submission of performance data is due by March 31, 2018. MACRA is complicated and here to stay. Learn and educate yourself to avoid downward payment adjustment. For full details, please visit https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf.

References

1. CMS MACRA Proposed Rule. http://1.usa.gov/1PpBpMt

2. CMS MACRA Executive Summary. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf

3. American Medical Association. http://bit.ly/1miEtBD

4. Policy and Medicine. MACRA http://bit.ly/1PTLkKa. MIPS http://bit.ly/20RoMzZ. APMs http://bit.ly/1OlxoxH

Frailty in lung transplantation

Two of the greatest challenges in lung transplantation are to identify optimal transplant candidates and to help those transplant recipients thrive in the years following surgery. Frailty is emerging as a marker of increased posttransplant morbidity and may represent an area where both the recipient selection process and posttransplant outcomes can be optimized. Described by some as “biologic age” rather than “chronologic age,” frailty is a syndrome of functional impairment and weakness that predisposes to adverse health outcomes. The adverse effects of frailty have been described in multiple clinical scenarios, including the ICU, chronic lung diseases, heart failure, liver transplant, kidney transplant, geriatrics, and others.

Remaining challenges include determining which clinical assessments best define frailty in the lung transplant population, documenting the adverse effects of frailty in well-designed multicenter prospective studies, and developing interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of frailty.

Asthma treatment during pregnancy

Asthma is common in pregnancy, occurring in 3% to 8% of pregnant women. While the course of asthma during pregnancy is variable, the objectives of asthma treatment do not change and aim to prevent acute exacerbations and optimize management. Uncontrolled asthma is associated with an increased risk of perinatal morbidity. Published guidelines on pharmacologic therapies during pregnancy recommend the same step-wise approach as in nonpregnant women.

The diagnosis of asthma, the use of other concurrent medications, and medication compliance may all be potential confounders. ICS use in pregnancy was associated with endocrine and metabolic disturbances in the offspring in a national cohort (Tegethoff M et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[5]:557-63). However, this study did not report on systemic steroid use, asthma severity, or details of these disturbances.

Mass shootings

There are multiple definitions for a mass shooting. Some definitions require a certain number of people be killed. Some definitions require a certain number of people be shot. Some definitions do not include gang violence. Regardless of the definition used, the number of mass shootings in the United States is increasing.

There are also multiple definitions of what qualifies as a medical disaster. These definitions can be summarized with the statement that a medical disaster is an event that produces a number of casualties that overwhelms the local health system.

Most mass shootings fit the definition of a medical disaster. When a mass shooting occurs, medical resources are diverted from current patients to those injured in the shooting. Patients with acute medical problems unrelated to the shooting must endure a prolonged wait for medical care.

The CHEST Disaster Response NetWork feels that it is necessary to take action to reduce the number of mass shootings. Unlike natural disasters, mass shootings are man-made. As such, we should proactively work to prevent them. Prevention is a large part of medicine. Working together with community leaders, law enforcement, and government officials, we can and should work to eliminate mass shootings so that we can minimize gun-related injury and death.

MACRA: Reincarnation of Medicare physician reimbursement model

In April 2015, President Obama signed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) eradicating the detested sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. If this is your first dive into MACRA as an eligible professional (EP), it may be a bit baffling trying to understand its impact on your practice.

Under MIPS, rules are divided into four categories. During the first year, each category will make up a certain percentage to the physician’s overall score, which will result in a penalty or payment as a lump sum in 2019. If you are an Advanced APM in 2017 and receive 25% of Medicare payments or see 20% of your Medicare patients through this model, you can earn up to a 5% incentive payment in 2019.

The performance period started on January 1, 2017. Submission of performance data is due by March 31, 2018. MACRA is complicated and here to stay. Learn and educate yourself to avoid downward payment adjustment. For full details, please visit https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf.

References

1. CMS MACRA Proposed Rule. http://1.usa.gov/1PpBpMt