User login

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

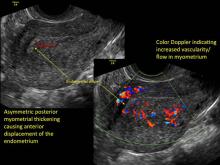

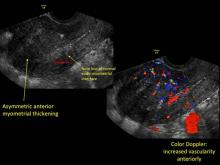

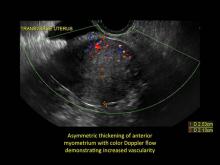

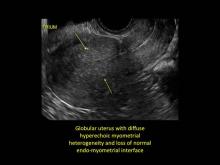

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

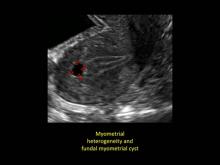

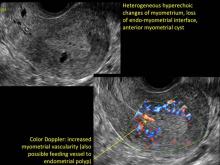

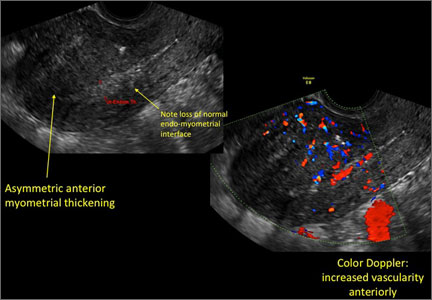

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

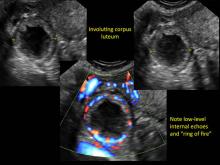

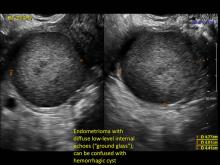

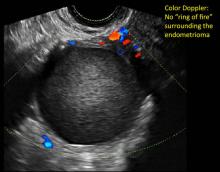

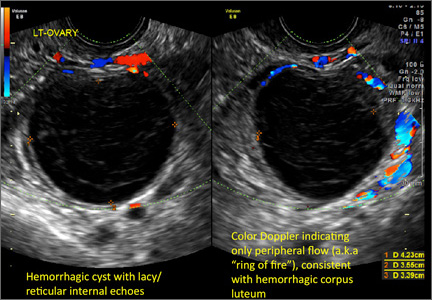

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

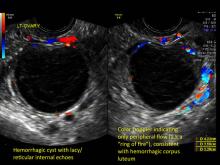

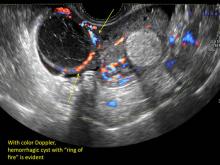

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

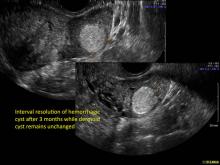

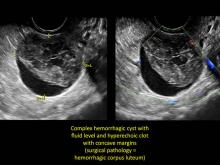

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal