User login

Reducing guesswork in schizophrenia treatment

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is moving from research into clinical practice as demand grows for objective rating scales. We see the PANSS becoming a treatment and planning tool for psychiatry, just as the electrocardiogram evolved into a measure of cardiac status in medical practice.

Based on our experience in co-authoring (LA Opler) and using the PANSS, we describe how you can use it to:

- identify psychotic symptoms for targeted treatment

- predict with greater accuracy how patients will respond to the treatment you provide.

Standardized Assessments

The PANSS first gained stature in studies that established the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).1-6 But its authors7 also envisioned the scale as a useful tool to help practicing clinicians treat patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Twenty years of experience has shown the PANSS to be a reliable and valid severity symptom scale for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other serious mental illnesses. It is particularly useful to track changes in positive and negative symptoms.8

Traditionally, psychiatric evaluation has been impressionistic and subjective, but standardized tools provide a common language while introducing objective, empiric measures of clinical status. Because patients with mental disorders are treated by providers from psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing, and other mental health disciplines, having standardized benchmarks to assess symptom severity can facilitate an integrated approach. And because the PANSS has been translated into some 40 languages and is being adopted in clinical settings worldwide, it provides a universal means of communicating information about a patient’s clinical status.

Panss Scoring System

The PANSS includes 30 items, each rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). In theory, a patient rated “absent” (or 1) on all items would receive a total score of 30, and a patient rated “extreme” (or 7) on all items would receive a total score of 210. In the real world, though, no one sees these extremes. Stable outpatients usually score 60 to 80. Inpatients’ scores rarely exceed 80 to 150, even in “treatment refractory” cases.

The 30 items are arranged as 7 positive symptom subscale items (P1-P7), 7 negative symptom subscale items (N1-N7), and 16 general psychopathology symptom items (G1-G16) (Table 1). Each item has a definition and a basis for rating. The first question you need to answer when rating a patient is whether the item is absent or present.

How it works. For example, the PANSS defines delusions as “beliefs that are unfounded, unrealistic, and idiosyncratic,” and the basis for rating is “thought content expressed during the interview and its influence on the patient’s social relations and behavior as reported from primary care workers or family.” If the definition does not apply to your patient, you rate this item 1 or absent. If the definition does apply, “anchoring points” for each level of severity are provided (Table 2), and you decide which anchoring point best describes the patient’s functioning during the interview and the preceding week.

Time required. In research, gathering informant information, conducting the interview, and generating reliable ratings takes 45 to 60 minutes. In clinical settings, if you know your patient and can function as informant and interviewer, you probably can obtain accurate ratings in 30 to 45 minutes.

Ideally, you would use the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), though clinicians who know this instrument well may prefer a less structured interview that covers all areas of inquiry. Accurate PANSS scores are easy to generate on all 30 items by combining information from the interview with information about how the patient has functioned in the past week.

PANSS ratings are not meant to be obtained after every patient contact but rather as often as needed to guide clinical treatment. For example, you might obtain a PANSS rating:

- when an inpatient is first admitted

- before starting a new medication

- weeks or months later to gauge the new treatment’s effect.

The PANSS manual—a complete individual kit costs approximately $200—or licenses to use multiple copies are available from the copyright holder, MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (see Related resources).

Table 1

Subscales of the 30-item Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

| 7 Positive symptom subscale items | 7 Negative symptom subscale items |

| P1. Delusions | N1. Blunted affect |

| P2. Conceptual disorganization | N2. Emotional withdrawal |

| P3. Hallucinatory behavior | N3. Poor rapport |

| P4. Excitement | N4. Passive/apathetic social withdrawal |

| P5. Grandiosity | N5. Difficulty in abstract thinking |

| P6. Suspiciousness/persecution | N6. Lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation |

| P7. Hostility | N7. Stereotyped thinking |

| 16 General psychopathology symptoms | |

| G1. Somatic concern | G9. Unusual thought content |

| G2. Anxiety | G10. Disorientation |

| G3. Guilt feelings | G11. Poor attention |

| G4. Tension | G12. Lack of judgment and insight |

| G5. Mannerisms and posturing | G13. Disturbance of volition |

| G6. Depression | G14. Poor impulse control |

| G7. Motor retardation | G15. Preoccupation |

| G8. Uncooperativeness | G16. Active social avoidance |

Table 2

7 levels of severity on the PANSS for characterizing delusions

| Severity level (“anchoring point”) | Description of patient function |

|---|---|

| 1 - Absent | The definition does not apply |

| 2 - Minimal | Questionable pathology; the patient may be at the upper extreme of normal limits |

| 3 - Mild | Presence of one or two delusions that are vague, uncrystallized, and not tenaciously held. The delusions do not interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 4 - Moderate | Presence of either a kaleidoscopic array of poorly formed, unstable delusions, or a few well-formed delusions that occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 5 - Moderate severe | Presence of numerous well-formed delusions that are tenaciously held and occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 6 - Severe | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are crystallized, possibly systematized, tenaciously held, and clearly interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 7 - Extreme | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are either highly systematized or very numerous, and that dominate major facets of the patient’s life. This behavior frequently results in inappropriate and irresponsible action that may jeopardize the safety of the patient or others |

Gauging Symptom Severity

Treatment planning. Clinicians at the Rochester (New York) Psychiatric Center use the PANSS to assess symptom severity in inpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Within 1 week of admission, patients are evaluated on the 30 items by a team of experienced PANSS raters. Symptoms identified by the PANSS become targets in individualized treatment plans. Follow-up PANSS assessments help determine if treatment has improved the selected symptoms.

Tracking patient progress. Florida State Hospital uses the PANSS to track progress of patients with serious mental illnesses. Data collected over 8 years from >19,000 PANSS assessments in a multilingual, multicultural population suggests that the PANSS:

- aids in decision making for medical and nonmedical aspects of care for individual patients

- can help determine if changes in agency prescribing practices affect patient symptom profiles and severity, one indicator of how policy and guidelines translate into patient care.9

Predicting Outcomes

The PANSS has been shown to predict course of illness and treatment response, functional outcomes (including aggression), and long-term outcomes (including deterioration). Adjusting treatments to achieve optimal PANSS scores also can help clinicians achieve remission of their patients’ psychotic symptoms (Box).11,12

Remission. Achieving and maintaining remission of schizophrenia has been hampered by a lack of specificity in existing scales. Andreasen et al11 recommend using selected items from the PANSS and other rating scales, including the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), and Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS).

Creating agreed-upon criteria will mean that clinicians will know what is meant by symptom remission, allowing for better communication and a standard to achieve.

Costs. Eventually, rating scales such as PANSS may provide “financial prognoses” to predict treatment costs over time. Mohr et al12 used PANSS scores to group 663 patients from public and private psychiatric hospitals into eight categories based on symptom severity. When each disease state was correlated with annual treatment costs, baseline assessment was a significant predictor of annualized cost as well as clinical outcome.

Functional outcomes. Steinert et al14 used the PANSS to rate 199 inpatients within 24 hours of admission into an acute psychiatric ward. After discharge, each patient was assessed retrospectively for aggressive behavior. The conceptual disorganization and hostility items from the positive sub-scale could predict violent behaviors during inpatient treatment with statistical significance.

Long-term outcomes. White et al15 assessed older schizophrenia inpatients, using the PANSS at baseline and after 1 year. The researchers looked specifically at the “activation factor”—six PANSS items including hostility, poor impulse control, excitement, uncooperativeness, poor rapport, and tension. Poor outcome and low discharge rates were directly correlated with high baseline scores on the PANSS activation factor (PANSS-AF).

Deterioration. Goetz et al16 showed that residual positive symptoms were significantly related to deteriorating course of illness, even when patients adhered to their medications. These results suggest that even subtle symptom elevations as measured by the PANSS can predict deterioration.

- The PANSS Institute. Information on how to attain, maintain, and retain high reliability as a PANSS rater. www.panss.org.

- MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (publisher and copyright holder) to purchase the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). www.mhs.com.

- Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Mougios VA. Measuring outcome in serious mental illness. In: IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer L (eds). Outcome measurement in psychiatry: a critical review. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2002.

Dr. Lewis A. Opler receives royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Inc. on sales of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Manual, the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), and the Informant Questionnaire for the PANSS (IQ-PANSS).

Dr. Mark G. Opler is Executive Director of The PANSS Institute.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by NIMH grant K24 MH01699 (DM).

1. van Kammen DP, McEvoy JP, Targum SD, et al. A randomized, controlled, dose-ranging trial of sertindole in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124(1-2):168-75.

2. Weiden PJ, Simpson GM, Potkin SG, et al. Effectiveness of switching to ziprasidone for stable but symptomatic outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(5):580-8.

3. Duggan L, Fenton M, Rathbone J, et al. Olanzapine for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Article No. CD001359.

4. Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):763-71.

5. Lasser R, Bossie CA, Gharabawi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone in stable patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord 2004;83(2-3):263-75.

6. Zalsman G, Carmon E, Martin A, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol 2003;13(3):319-27.

7. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) manual. Toronto, Ontario: MultiHealth Systems, Inc.; 2006.

8. Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q 1990;61(3):163-78.

9. Annis LV. Implementation of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in a state psychiatric hospital: eight years of data and experience. Paper presented at: 16th Annual Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research, Program Evaluation and Policy, 2006.

10. Zalsman G, Posmanik S, Fisch T, et al. Psychosocial situations, quality of depression and schizophrenia in adolescents. Psychiatry Res 2003;129:149-157.

11. Andreason N, Carpenter W, Kane J, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:441-9.

12. Mohr PE, Cheng CM, Claxton K, et al. The heterogeneity of schizophrenia in disease states. Schizophr Res 2004;71:83-95.

13. Hatta K, Nakamura H, Matsuzaki I. Acute-phase treatment in general hospitals: clinical psychopharmacologic evaluation in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:39-45.

14. Steinert T, Wolfle M, Gebhardt R-P. Measurement of violence during inpatient treatment and association with psychopathology. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:107-12.

15. White L, Opler L, Harvey P, et al. Activation symptoms and discharge in early chronic schizophrenia inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(12):880-3.

16. Goetz D, Goetz R, Yale S, et al. Comparing early and chronic psychosis clinical characteristics. Schizophr Res 2004;70:120.-

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is moving from research into clinical practice as demand grows for objective rating scales. We see the PANSS becoming a treatment and planning tool for psychiatry, just as the electrocardiogram evolved into a measure of cardiac status in medical practice.

Based on our experience in co-authoring (LA Opler) and using the PANSS, we describe how you can use it to:

- identify psychotic symptoms for targeted treatment

- predict with greater accuracy how patients will respond to the treatment you provide.

Standardized Assessments

The PANSS first gained stature in studies that established the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).1-6 But its authors7 also envisioned the scale as a useful tool to help practicing clinicians treat patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Twenty years of experience has shown the PANSS to be a reliable and valid severity symptom scale for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other serious mental illnesses. It is particularly useful to track changes in positive and negative symptoms.8

Traditionally, psychiatric evaluation has been impressionistic and subjective, but standardized tools provide a common language while introducing objective, empiric measures of clinical status. Because patients with mental disorders are treated by providers from psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing, and other mental health disciplines, having standardized benchmarks to assess symptom severity can facilitate an integrated approach. And because the PANSS has been translated into some 40 languages and is being adopted in clinical settings worldwide, it provides a universal means of communicating information about a patient’s clinical status.

Panss Scoring System

The PANSS includes 30 items, each rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). In theory, a patient rated “absent” (or 1) on all items would receive a total score of 30, and a patient rated “extreme” (or 7) on all items would receive a total score of 210. In the real world, though, no one sees these extremes. Stable outpatients usually score 60 to 80. Inpatients’ scores rarely exceed 80 to 150, even in “treatment refractory” cases.

The 30 items are arranged as 7 positive symptom subscale items (P1-P7), 7 negative symptom subscale items (N1-N7), and 16 general psychopathology symptom items (G1-G16) (Table 1). Each item has a definition and a basis for rating. The first question you need to answer when rating a patient is whether the item is absent or present.

How it works. For example, the PANSS defines delusions as “beliefs that are unfounded, unrealistic, and idiosyncratic,” and the basis for rating is “thought content expressed during the interview and its influence on the patient’s social relations and behavior as reported from primary care workers or family.” If the definition does not apply to your patient, you rate this item 1 or absent. If the definition does apply, “anchoring points” for each level of severity are provided (Table 2), and you decide which anchoring point best describes the patient’s functioning during the interview and the preceding week.

Time required. In research, gathering informant information, conducting the interview, and generating reliable ratings takes 45 to 60 minutes. In clinical settings, if you know your patient and can function as informant and interviewer, you probably can obtain accurate ratings in 30 to 45 minutes.

Ideally, you would use the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), though clinicians who know this instrument well may prefer a less structured interview that covers all areas of inquiry. Accurate PANSS scores are easy to generate on all 30 items by combining information from the interview with information about how the patient has functioned in the past week.

PANSS ratings are not meant to be obtained after every patient contact but rather as often as needed to guide clinical treatment. For example, you might obtain a PANSS rating:

- when an inpatient is first admitted

- before starting a new medication

- weeks or months later to gauge the new treatment’s effect.

The PANSS manual—a complete individual kit costs approximately $200—or licenses to use multiple copies are available from the copyright holder, MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (see Related resources).

Table 1

Subscales of the 30-item Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

| 7 Positive symptom subscale items | 7 Negative symptom subscale items |

| P1. Delusions | N1. Blunted affect |

| P2. Conceptual disorganization | N2. Emotional withdrawal |

| P3. Hallucinatory behavior | N3. Poor rapport |

| P4. Excitement | N4. Passive/apathetic social withdrawal |

| P5. Grandiosity | N5. Difficulty in abstract thinking |

| P6. Suspiciousness/persecution | N6. Lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation |

| P7. Hostility | N7. Stereotyped thinking |

| 16 General psychopathology symptoms | |

| G1. Somatic concern | G9. Unusual thought content |

| G2. Anxiety | G10. Disorientation |

| G3. Guilt feelings | G11. Poor attention |

| G4. Tension | G12. Lack of judgment and insight |

| G5. Mannerisms and posturing | G13. Disturbance of volition |

| G6. Depression | G14. Poor impulse control |

| G7. Motor retardation | G15. Preoccupation |

| G8. Uncooperativeness | G16. Active social avoidance |

Table 2

7 levels of severity on the PANSS for characterizing delusions

| Severity level (“anchoring point”) | Description of patient function |

|---|---|

| 1 - Absent | The definition does not apply |

| 2 - Minimal | Questionable pathology; the patient may be at the upper extreme of normal limits |

| 3 - Mild | Presence of one or two delusions that are vague, uncrystallized, and not tenaciously held. The delusions do not interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 4 - Moderate | Presence of either a kaleidoscopic array of poorly formed, unstable delusions, or a few well-formed delusions that occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 5 - Moderate severe | Presence of numerous well-formed delusions that are tenaciously held and occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 6 - Severe | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are crystallized, possibly systematized, tenaciously held, and clearly interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 7 - Extreme | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are either highly systematized or very numerous, and that dominate major facets of the patient’s life. This behavior frequently results in inappropriate and irresponsible action that may jeopardize the safety of the patient or others |

Gauging Symptom Severity

Treatment planning. Clinicians at the Rochester (New York) Psychiatric Center use the PANSS to assess symptom severity in inpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Within 1 week of admission, patients are evaluated on the 30 items by a team of experienced PANSS raters. Symptoms identified by the PANSS become targets in individualized treatment plans. Follow-up PANSS assessments help determine if treatment has improved the selected symptoms.

Tracking patient progress. Florida State Hospital uses the PANSS to track progress of patients with serious mental illnesses. Data collected over 8 years from >19,000 PANSS assessments in a multilingual, multicultural population suggests that the PANSS:

- aids in decision making for medical and nonmedical aspects of care for individual patients

- can help determine if changes in agency prescribing practices affect patient symptom profiles and severity, one indicator of how policy and guidelines translate into patient care.9

Predicting Outcomes

The PANSS has been shown to predict course of illness and treatment response, functional outcomes (including aggression), and long-term outcomes (including deterioration). Adjusting treatments to achieve optimal PANSS scores also can help clinicians achieve remission of their patients’ psychotic symptoms (Box).11,12

Remission. Achieving and maintaining remission of schizophrenia has been hampered by a lack of specificity in existing scales. Andreasen et al11 recommend using selected items from the PANSS and other rating scales, including the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), and Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS).

Creating agreed-upon criteria will mean that clinicians will know what is meant by symptom remission, allowing for better communication and a standard to achieve.

Costs. Eventually, rating scales such as PANSS may provide “financial prognoses” to predict treatment costs over time. Mohr et al12 used PANSS scores to group 663 patients from public and private psychiatric hospitals into eight categories based on symptom severity. When each disease state was correlated with annual treatment costs, baseline assessment was a significant predictor of annualized cost as well as clinical outcome.

Functional outcomes. Steinert et al14 used the PANSS to rate 199 inpatients within 24 hours of admission into an acute psychiatric ward. After discharge, each patient was assessed retrospectively for aggressive behavior. The conceptual disorganization and hostility items from the positive sub-scale could predict violent behaviors during inpatient treatment with statistical significance.

Long-term outcomes. White et al15 assessed older schizophrenia inpatients, using the PANSS at baseline and after 1 year. The researchers looked specifically at the “activation factor”—six PANSS items including hostility, poor impulse control, excitement, uncooperativeness, poor rapport, and tension. Poor outcome and low discharge rates were directly correlated with high baseline scores on the PANSS activation factor (PANSS-AF).

Deterioration. Goetz et al16 showed that residual positive symptoms were significantly related to deteriorating course of illness, even when patients adhered to their medications. These results suggest that even subtle symptom elevations as measured by the PANSS can predict deterioration.

- The PANSS Institute. Information on how to attain, maintain, and retain high reliability as a PANSS rater. www.panss.org.

- MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (publisher and copyright holder) to purchase the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). www.mhs.com.

- Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Mougios VA. Measuring outcome in serious mental illness. In: IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer L (eds). Outcome measurement in psychiatry: a critical review. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2002.

Dr. Lewis A. Opler receives royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Inc. on sales of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Manual, the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), and the Informant Questionnaire for the PANSS (IQ-PANSS).

Dr. Mark G. Opler is Executive Director of The PANSS Institute.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by NIMH grant K24 MH01699 (DM).

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is moving from research into clinical practice as demand grows for objective rating scales. We see the PANSS becoming a treatment and planning tool for psychiatry, just as the electrocardiogram evolved into a measure of cardiac status in medical practice.

Based on our experience in co-authoring (LA Opler) and using the PANSS, we describe how you can use it to:

- identify psychotic symptoms for targeted treatment

- predict with greater accuracy how patients will respond to the treatment you provide.

Standardized Assessments

The PANSS first gained stature in studies that established the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).1-6 But its authors7 also envisioned the scale as a useful tool to help practicing clinicians treat patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Twenty years of experience has shown the PANSS to be a reliable and valid severity symptom scale for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other serious mental illnesses. It is particularly useful to track changes in positive and negative symptoms.8

Traditionally, psychiatric evaluation has been impressionistic and subjective, but standardized tools provide a common language while introducing objective, empiric measures of clinical status. Because patients with mental disorders are treated by providers from psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing, and other mental health disciplines, having standardized benchmarks to assess symptom severity can facilitate an integrated approach. And because the PANSS has been translated into some 40 languages and is being adopted in clinical settings worldwide, it provides a universal means of communicating information about a patient’s clinical status.

Panss Scoring System

The PANSS includes 30 items, each rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). In theory, a patient rated “absent” (or 1) on all items would receive a total score of 30, and a patient rated “extreme” (or 7) on all items would receive a total score of 210. In the real world, though, no one sees these extremes. Stable outpatients usually score 60 to 80. Inpatients’ scores rarely exceed 80 to 150, even in “treatment refractory” cases.

The 30 items are arranged as 7 positive symptom subscale items (P1-P7), 7 negative symptom subscale items (N1-N7), and 16 general psychopathology symptom items (G1-G16) (Table 1). Each item has a definition and a basis for rating. The first question you need to answer when rating a patient is whether the item is absent or present.

How it works. For example, the PANSS defines delusions as “beliefs that are unfounded, unrealistic, and idiosyncratic,” and the basis for rating is “thought content expressed during the interview and its influence on the patient’s social relations and behavior as reported from primary care workers or family.” If the definition does not apply to your patient, you rate this item 1 or absent. If the definition does apply, “anchoring points” for each level of severity are provided (Table 2), and you decide which anchoring point best describes the patient’s functioning during the interview and the preceding week.

Time required. In research, gathering informant information, conducting the interview, and generating reliable ratings takes 45 to 60 minutes. In clinical settings, if you know your patient and can function as informant and interviewer, you probably can obtain accurate ratings in 30 to 45 minutes.

Ideally, you would use the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), though clinicians who know this instrument well may prefer a less structured interview that covers all areas of inquiry. Accurate PANSS scores are easy to generate on all 30 items by combining information from the interview with information about how the patient has functioned in the past week.

PANSS ratings are not meant to be obtained after every patient contact but rather as often as needed to guide clinical treatment. For example, you might obtain a PANSS rating:

- when an inpatient is first admitted

- before starting a new medication

- weeks or months later to gauge the new treatment’s effect.

The PANSS manual—a complete individual kit costs approximately $200—or licenses to use multiple copies are available from the copyright holder, MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (see Related resources).

Table 1

Subscales of the 30-item Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

| 7 Positive symptom subscale items | 7 Negative symptom subscale items |

| P1. Delusions | N1. Blunted affect |

| P2. Conceptual disorganization | N2. Emotional withdrawal |

| P3. Hallucinatory behavior | N3. Poor rapport |

| P4. Excitement | N4. Passive/apathetic social withdrawal |

| P5. Grandiosity | N5. Difficulty in abstract thinking |

| P6. Suspiciousness/persecution | N6. Lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation |

| P7. Hostility | N7. Stereotyped thinking |

| 16 General psychopathology symptoms | |

| G1. Somatic concern | G9. Unusual thought content |

| G2. Anxiety | G10. Disorientation |

| G3. Guilt feelings | G11. Poor attention |

| G4. Tension | G12. Lack of judgment and insight |

| G5. Mannerisms and posturing | G13. Disturbance of volition |

| G6. Depression | G14. Poor impulse control |

| G7. Motor retardation | G15. Preoccupation |

| G8. Uncooperativeness | G16. Active social avoidance |

Table 2

7 levels of severity on the PANSS for characterizing delusions

| Severity level (“anchoring point”) | Description of patient function |

|---|---|

| 1 - Absent | The definition does not apply |

| 2 - Minimal | Questionable pathology; the patient may be at the upper extreme of normal limits |

| 3 - Mild | Presence of one or two delusions that are vague, uncrystallized, and not tenaciously held. The delusions do not interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 4 - Moderate | Presence of either a kaleidoscopic array of poorly formed, unstable delusions, or a few well-formed delusions that occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 5 - Moderate severe | Presence of numerous well-formed delusions that are tenaciously held and occasionally interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 6 - Severe | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are crystallized, possibly systematized, tenaciously held, and clearly interfere with the patient’s thinking, social relations, or behavior |

| 7 - Extreme | Presence of a stable set of delusions that are either highly systematized or very numerous, and that dominate major facets of the patient’s life. This behavior frequently results in inappropriate and irresponsible action that may jeopardize the safety of the patient or others |

Gauging Symptom Severity

Treatment planning. Clinicians at the Rochester (New York) Psychiatric Center use the PANSS to assess symptom severity in inpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Within 1 week of admission, patients are evaluated on the 30 items by a team of experienced PANSS raters. Symptoms identified by the PANSS become targets in individualized treatment plans. Follow-up PANSS assessments help determine if treatment has improved the selected symptoms.

Tracking patient progress. Florida State Hospital uses the PANSS to track progress of patients with serious mental illnesses. Data collected over 8 years from >19,000 PANSS assessments in a multilingual, multicultural population suggests that the PANSS:

- aids in decision making for medical and nonmedical aspects of care for individual patients

- can help determine if changes in agency prescribing practices affect patient symptom profiles and severity, one indicator of how policy and guidelines translate into patient care.9

Predicting Outcomes

The PANSS has been shown to predict course of illness and treatment response, functional outcomes (including aggression), and long-term outcomes (including deterioration). Adjusting treatments to achieve optimal PANSS scores also can help clinicians achieve remission of their patients’ psychotic symptoms (Box).11,12

Remission. Achieving and maintaining remission of schizophrenia has been hampered by a lack of specificity in existing scales. Andreasen et al11 recommend using selected items from the PANSS and other rating scales, including the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS), and Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS).

Creating agreed-upon criteria will mean that clinicians will know what is meant by symptom remission, allowing for better communication and a standard to achieve.

Costs. Eventually, rating scales such as PANSS may provide “financial prognoses” to predict treatment costs over time. Mohr et al12 used PANSS scores to group 663 patients from public and private psychiatric hospitals into eight categories based on symptom severity. When each disease state was correlated with annual treatment costs, baseline assessment was a significant predictor of annualized cost as well as clinical outcome.

Functional outcomes. Steinert et al14 used the PANSS to rate 199 inpatients within 24 hours of admission into an acute psychiatric ward. After discharge, each patient was assessed retrospectively for aggressive behavior. The conceptual disorganization and hostility items from the positive sub-scale could predict violent behaviors during inpatient treatment with statistical significance.

Long-term outcomes. White et al15 assessed older schizophrenia inpatients, using the PANSS at baseline and after 1 year. The researchers looked specifically at the “activation factor”—six PANSS items including hostility, poor impulse control, excitement, uncooperativeness, poor rapport, and tension. Poor outcome and low discharge rates were directly correlated with high baseline scores on the PANSS activation factor (PANSS-AF).

Deterioration. Goetz et al16 showed that residual positive symptoms were significantly related to deteriorating course of illness, even when patients adhered to their medications. These results suggest that even subtle symptom elevations as measured by the PANSS can predict deterioration.

- The PANSS Institute. Information on how to attain, maintain, and retain high reliability as a PANSS rater. www.panss.org.

- MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (publisher and copyright holder) to purchase the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). www.mhs.com.

- Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Mougios VA. Measuring outcome in serious mental illness. In: IsHak WW, Burt T, Sederer L (eds). Outcome measurement in psychiatry: a critical review. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2002.

Dr. Lewis A. Opler receives royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Inc. on sales of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Manual, the Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS (SCI-PANSS), and the Informant Questionnaire for the PANSS (IQ-PANSS).

Dr. Mark G. Opler is Executive Director of The PANSS Institute.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by NIMH grant K24 MH01699 (DM).

1. van Kammen DP, McEvoy JP, Targum SD, et al. A randomized, controlled, dose-ranging trial of sertindole in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124(1-2):168-75.

2. Weiden PJ, Simpson GM, Potkin SG, et al. Effectiveness of switching to ziprasidone for stable but symptomatic outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(5):580-8.

3. Duggan L, Fenton M, Rathbone J, et al. Olanzapine for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Article No. CD001359.

4. Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):763-71.

5. Lasser R, Bossie CA, Gharabawi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone in stable patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord 2004;83(2-3):263-75.

6. Zalsman G, Carmon E, Martin A, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol 2003;13(3):319-27.

7. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) manual. Toronto, Ontario: MultiHealth Systems, Inc.; 2006.

8. Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q 1990;61(3):163-78.

9. Annis LV. Implementation of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in a state psychiatric hospital: eight years of data and experience. Paper presented at: 16th Annual Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research, Program Evaluation and Policy, 2006.

10. Zalsman G, Posmanik S, Fisch T, et al. Psychosocial situations, quality of depression and schizophrenia in adolescents. Psychiatry Res 2003;129:149-157.

11. Andreason N, Carpenter W, Kane J, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:441-9.

12. Mohr PE, Cheng CM, Claxton K, et al. The heterogeneity of schizophrenia in disease states. Schizophr Res 2004;71:83-95.

13. Hatta K, Nakamura H, Matsuzaki I. Acute-phase treatment in general hospitals: clinical psychopharmacologic evaluation in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:39-45.

14. Steinert T, Wolfle M, Gebhardt R-P. Measurement of violence during inpatient treatment and association with psychopathology. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:107-12.

15. White L, Opler L, Harvey P, et al. Activation symptoms and discharge in early chronic schizophrenia inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(12):880-3.

16. Goetz D, Goetz R, Yale S, et al. Comparing early and chronic psychosis clinical characteristics. Schizophr Res 2004;70:120.-

1. van Kammen DP, McEvoy JP, Targum SD, et al. A randomized, controlled, dose-ranging trial of sertindole in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124(1-2):168-75.

2. Weiden PJ, Simpson GM, Potkin SG, et al. Effectiveness of switching to ziprasidone for stable but symptomatic outpatients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(5):580-8.

3. Duggan L, Fenton M, Rathbone J, et al. Olanzapine for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Article No. CD001359.

4. Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(9):763-71.

5. Lasser R, Bossie CA, Gharabawi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-acting risperidone in stable patients with schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord 2004;83(2-3):263-75.

6. Zalsman G, Carmon E, Martin A, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol 2003;13(3):319-27.

7. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) manual. Toronto, Ontario: MultiHealth Systems, Inc.; 2006.

8. Kay SR. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr Q 1990;61(3):163-78.

9. Annis LV. Implementation of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in a state psychiatric hospital: eight years of data and experience. Paper presented at: 16th Annual Conference on State Mental Health Agency Services Research, Program Evaluation and Policy, 2006.

10. Zalsman G, Posmanik S, Fisch T, et al. Psychosocial situations, quality of depression and schizophrenia in adolescents. Psychiatry Res 2003;129:149-157.

11. Andreason N, Carpenter W, Kane J, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:441-9.

12. Mohr PE, Cheng CM, Claxton K, et al. The heterogeneity of schizophrenia in disease states. Schizophr Res 2004;71:83-95.

13. Hatta K, Nakamura H, Matsuzaki I. Acute-phase treatment in general hospitals: clinical psychopharmacologic evaluation in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:39-45.

14. Steinert T, Wolfle M, Gebhardt R-P. Measurement of violence during inpatient treatment and association with psychopathology. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102:107-12.

15. White L, Opler L, Harvey P, et al. Activation symptoms and discharge in early chronic schizophrenia inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004;192(12):880-3.

16. Goetz D, Goetz R, Yale S, et al. Comparing early and chronic psychosis clinical characteristics. Schizophr Res 2004;70:120.-

Hepatitis C and interferon: Watch for hostility, impulsivity

Pegylated interferon-alpha with ribavirin is the most effective therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection,1,2 but psychiatric patients often discontinue IFN-alpha because of its mood side effects.3 Most studies describe depressive states, although manic symptoms—irritability, aggression, anger, hostility, emotional lability, anxiety, panic attacks, and insomnia—also have been reported.4-6

To help you manage adverse mood changes and prevent IFN-alpha treatment discontinuation in patients with hepatitis C, this article:

- reviews studies of patients with a history mood disorders who were treated with IFN-alpha

- explains how to recognize and treat IFN-alpha-induced mood disturbances when antidepressants are contraindicated.

Psychiatric Patients and IFN Therapy

Chronic hepatitis C infection is common among psychiatric patients. Routine screening among 1,556 patients admitted to a U.S. public psychiatric hospital across 3 years identified 133 patients (8.5%) who were positive for hepatitis C virus.7

Patients with psychopathologic symptoms before starting IFN therapy may suffer more-severe adverse psychiatric effects during treatment than those without psychopathology.8 In fact, mood disorders were considered an absolute contraindication to IFN therapy until recently.

Now that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended extending hepatitis C research and treatment to psychiatric patients, IFN-alpha-induced mental illness could become more common in clinical practice. Before the 2002 NIH consensus statement, patients with mental illness and substance use disorders—who represent >50% of candidates who need IFN therapy—were excluded from research protocols.

Safely using IFN. Some reports and studies suggest that patients with past or existing psychiatric disorders can be treated safely and effectively with IFN-alpha.

In a prospective open-label study, 29 of 31 patients with co-existing chronic hepatitis C and psychiatric illness completed 6 months of IFN therapy, 5 million units (MU) three times/week or 5 MU daily. Patients continued maintenance psychotropics during IFN treatment, and a psychiatrist monitored psychiatric symptoms.

Psychiatric illness worsened in four patients, and two discontinued IFN treatment. Serum alanine aminotransferase returned to normal in 22 patients (71%), and hepatitis C virus RNA cleared from the sera of 15 (48%).9

Another prospective study of 50 patients treated with IFN for chronic hepatitis found that those with a pre-existing mood or anxiety disorder were not more likely than others to discontinue IFN therapy.10

Unique to hepatitis therapy? IFN-induced mood disturbances are probably different in patients with chronic hepatitis C than in those receiving IFN for other diseases because of differences in regimens and effects of the underlying pathologies. For example, prescribing a preventative antidepressant before starting IFN treatment might help cancer patients but not patients with hepatitis C.11

This distinction could be particularly important when giving IFN-alpha to patients who are vulnerable to psychiatric illness with impulsive features. To emphasize this point, we describe clinical features and treatment response in patients with hepatitis C who were treated in our department.

IFN-Alpha-Induced Moods

In our prospective study of 93 patients, 30 (32%) developed IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders during the first 12 weeks of treatment.12 Contrary to previous studies focusing on depression, most of our patients had a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Twenty-four (13 women and 11 men, mean age 43) accepted referral to a psychiatrist specializing in mood disorders to characterize their symptoms.

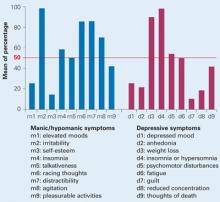

Mood characteristics. Using DSM-IV criteria, the psychiatrist determined that IFN-alpha induced both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in many patients, and the manic/hypomanic features predominated. Five manic symptoms and three depressive symptoms were present in >50% of patients (Figure 1, Table 1).

Three patients presented with a manic episode,15 with hypomania with prevalent irritability and dysphoric features, and 6 with a mixed depressive state (major depressive episode with at least 3 hypomania symptoms).13 Four patients (17%) suffered a relapse of alcohol or cannabis abuse.

Nearly all (84%) reported paroxysmal anxiety, and all had emotional hyperreactivity that the psychiatrist described as a main symptom of a manic or mixed state.14 Most felt extremely impulsive and feared losing control. Two faced legal difficulties, and one was in prison.

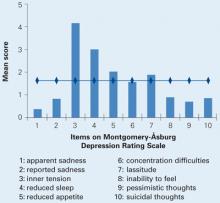

The patients’ mean Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score was 16.12 (±1.6), indicating a mild to moderate depressive state. The highest-scoring items were inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, and lassitude (Figure 2).

Their mean Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale15 score was 14.33 (±1.3), indicating hypomanic or moderate manic symptoms. Hostility was by far the predominant manic symptom (mean score 3.2/4). Other manic symptom scores ranged from 0.2/4 to 2.1/4 (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Mood symptoms identified in 24 patients after 12 weeks of IFN-alpha treatment

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 2 Depressive symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 3 Manic symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12Table 1

Most-prevalent IFN-induced mood symptoms in 24 patients treated for hepatitis C

| 5 manic symptoms (% of patients) | 3 depressive symptoms (% of patients) |

| Irritability (100%) | Insomnia or hypersomnia (100%) |

| Racing thoughts (87%) | Poor appetite or weight loss (92%) |

| Distractibility (87%) | Psychomotor agitation or retardation (54%) |

| Insomnia (58%) | |

| Agitation (70%) | |

| IFN: Interferon | |

| Source: Reference 12 | |

Treatment. Given the predominance of manic/hypomanic symptoms, we treated the 24 patients with low-to-moderate dosages of an atypical antipsychotic (amisulpride, 100 to 600 mg/d). This medication—not available in the United States—would be similar to using risperidone, 1 to 6 mg/d. Low-dose benzodiazepines (clonazepam or alprazolam) were added as needed to manage insomnia. Antipsychotic treatment enabled 23 of 24 patients (96%) to continue antiviral therapy.

Five patients had received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for 1 to 4 weeks before referral to the psychiatrist. Antidepressants worsened their mood symptoms, which included impulsivity, agitation, and insomnia. Emotional hyper-reactivity, irritability, hostility, and impulsiveness improved in all 5 patients within 1 to 2 weeks of stopping SSRIs and starting the atypical antipsychotic.

Discussion

Accurately characterizing IFN-induced mood states confirmed our published data showing a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients treated for chronic hepatitis C. Irritability and hostility were the two most prominent symptoms.

These findings differ from those of investigations that identified depressive symptoms as the hallmark of IFN’s psychiatric side effects.6 Our data were thoroughly characterized according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, two mood-rating scales, and a psychiatrist experienced in mood disorders.

Why is mania missed? One possible explanation for these different findings is that IFN-alpha-induced fatigue and flu-like symptoms could be misinterpreted as depressive symptoms. Also, most researchers have used depression rating scales—but not mania scales—and have not considered other psychiatric diagnostics.16

Self-report questionnaires for evaluating depression also take into account somatic side effects, resulting in higher rating scores. Moreover, few studies have included clinical psychiatric interviews and even fewer diagnostic confirmation by a psychiatrist.

Finally, clinical experience indicates that patients who present with both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms are more likely to complain about depression than about manic symptoms. Therefore, clinicians may miss manic symptoms if they don’t actively seek them.

Irritability and hostility. Previous studies have described irritability, mood lability, and anger/hostility as frequent symptoms4,5 but failed to consider them as possible manifestations of mania or hypomania. Many of our patients reported irritability severe enough to interfere with their work, social, and family relationships.

Hostility was the symptom with the highest score on the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale. This objective evidence suggests that investigating the consequences to patients of increased irritability, impulsivity, or hostility might reveal some frightening behavior

How to treat these patients. Considerable evidence from characterizing IFN-induced side effects in patients with hepatitis C points to a syndrome of depressive and manic/hypomanic symptoms13,17-19 that does not fulfill criteria for a mixed state. This disorder is not described in DSM-IV-TR and, unfortunately, usually is misdiagnosed as a depressive state.

Antidepressants can worsen depression by causing agitation and impulsivity and can increase risk of suicide.17,18,20 By contrast, atypical antipsychotics have been shown to improve bipolar depression.21,22

We used an atypical antipsychotic to treat patients with prevalent manic or hypomanic symptoms and those who did not respond to SSRIs. Their IFN-induced mood disorders improved rapidly on low dosages of amisulpride, and antiviral therapy discontinuation rates were low (1/24; 4%). By comparison, other studies have reported antiviral treatment discontinuation rates of 30% to 40% in patients taking antidepressants.23,24

The atypical antipsychotic did not improve our patients’ fatigue and other neurovegetative symptoms, but antidepressants likewise do not improve these symptoms.8

Recommendations

This study leads us to warn clinicians that antidepressants can worsen IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders and to recommend that antipsychotics be considered:

- at least before you decide to discontinue a hepatitis C patient’s IFN-alpha therapy

- or in patients with high irritability and hostility.

To determine whether to use an antidepressant or antimanic agent as first-line treatment, carefully diagnose the patient’s symptoms as a manic/hypomanic state, depressive mixed state, or depression. Successful IFN therapy requires:

- psychological support

- medication for psychiatric adverse effects

- collaboration between the psychiatrist and hepatologist.

IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders are triggered exogenously, do not correspond to typical features of any classic psychiatric disorder, and require further study. IFN-induced impulsivity and hostility also need to be better characterized, particularly as more patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders are treated for hepatitis C.

Related resources

- Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001;345(1):41-52.

- Onyike CU, Bonner JO, Lyketsos CG, Treisman GJ. Mania during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:3.

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amisulpride • (not available in the United States)

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted with support from the Centre d’Investigation Clinique INSERM/CHU de Bordeaux.

1. Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-65.

2. Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-82.

3. Zdilar D, Franco-Bronson K, Buchler N, et al. Hepatitis C, interferon alfa, and depression. Hepatology. 2000;31:1207-11.

4. Schaefer M, Engelbrecht MA, Gut O, et al. Interferon alpha (INF-alpha) and psychiatric syndromes: a review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:731-46.

5. Trask PC, Esper P, Riba M, Redman B. Psychiatric side effects of interferon therapy: prevalence, proposed mechanisms, and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2316-26.

6. Kraus MR, Schäfer A, Faler H, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving interferon alfa-2B therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:6.-

7. Dinwiddie SH, Shicker L, Newman T. Prevalence of hepatitis C among psychiatric patients in the public sector. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):172-4.

8. Capuron L, Gummick JF, Musselman DL, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of interferon-alpha in cancer patients: phenomenology and paroxetine responsiveness of symptom dimensions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:643-52.

9. Van Thiel DH, Friedlander L, Molloy PJ, et al. Interferon-alpha can be used successfully in patients with hepatitis C virus-positive chronic hepatitis who have a psychiatric illness. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7(2):165-8.

10. Pariante CM, Landau S, Carpiniello B. Interferon alfa-induced adverse effects in patients with a psychiatric diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):148-9.

11. Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Gumnick JF, et al. Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced by high-dose interferon-alfa. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(13):961-6.

12. Constant A, Castera L, Dantzer R, et al. Mood alterations during interferon-alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: evidence for an overlap between manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66;8:1050-7.

13. Benazzi F. Major depressive episodes with hypomanic symptoms are common among depressed outpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42(2):139-43.

14. Henry C, Swendsen J, Van Den Bulke D, et al. Emotional hyperreactivity as the fundamental mood characteristic of manic and mixed states. Eur Psychiat. 2003;18:124-8.

15. Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ, Kramp P, Bolwig TG. The mania rating scale: scale construction and inter-observer agreement. Neuropharmacology. 1978;17:430-1.

16. Castera L, Constant A, Henry C, et al. Incidence, risk factors and treatment of mood disorders associated with peginterferon and ribavirin therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: results of a prospective study (abstract). Hepatology. 2003;38 (suppl.1):735A.-

17. Koukopoulos A, Koukopoulos A. Agitated depression as a mixed state and the problem of melancholia. Bipolarity: beyond classic mania. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22(3):564-74.

18. Benazzi F, Koukopoulos A, Akiskal HS. Toward a validation of a new definition of agitated depression as a bipolar mixed state (mixed depression). European Psychiatry. 2004;19:85-90.

19. Suppes T, Mintz J, McElroy SL, et al. Mixed hypomania in 908 patients with bipolar disorder evaluated prospectively in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Network. A sex-specific phenomenon. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1089-96.

20. Henry C, Demotes-Mainard J. Avoiding drug-induced switching in patients with bipolar depression. Drug Safety. 2003;26:337-51.

21. Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1079-88.

22. Calabrese JR, Keck PE, Jr, MacFadden W, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression, Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1351-60.

23. Kraus MR, Schafer A, Faller H, et al. Paroxetine for the treatment of interferon-alpha-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1091-9.

24. Hauser P, Khosla J, Aurora H, et al. A prospective study of the incidence and open-label treatment of interferon-induced major depressive disorder in patients with hepatitis C. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:942-7.

Pegylated interferon-alpha with ribavirin is the most effective therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection,1,2 but psychiatric patients often discontinue IFN-alpha because of its mood side effects.3 Most studies describe depressive states, although manic symptoms—irritability, aggression, anger, hostility, emotional lability, anxiety, panic attacks, and insomnia—also have been reported.4-6

To help you manage adverse mood changes and prevent IFN-alpha treatment discontinuation in patients with hepatitis C, this article:

- reviews studies of patients with a history mood disorders who were treated with IFN-alpha

- explains how to recognize and treat IFN-alpha-induced mood disturbances when antidepressants are contraindicated.

Psychiatric Patients and IFN Therapy

Chronic hepatitis C infection is common among psychiatric patients. Routine screening among 1,556 patients admitted to a U.S. public psychiatric hospital across 3 years identified 133 patients (8.5%) who were positive for hepatitis C virus.7

Patients with psychopathologic symptoms before starting IFN therapy may suffer more-severe adverse psychiatric effects during treatment than those without psychopathology.8 In fact, mood disorders were considered an absolute contraindication to IFN therapy until recently.

Now that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended extending hepatitis C research and treatment to psychiatric patients, IFN-alpha-induced mental illness could become more common in clinical practice. Before the 2002 NIH consensus statement, patients with mental illness and substance use disorders—who represent >50% of candidates who need IFN therapy—were excluded from research protocols.

Safely using IFN. Some reports and studies suggest that patients with past or existing psychiatric disorders can be treated safely and effectively with IFN-alpha.

In a prospective open-label study, 29 of 31 patients with co-existing chronic hepatitis C and psychiatric illness completed 6 months of IFN therapy, 5 million units (MU) three times/week or 5 MU daily. Patients continued maintenance psychotropics during IFN treatment, and a psychiatrist monitored psychiatric symptoms.

Psychiatric illness worsened in four patients, and two discontinued IFN treatment. Serum alanine aminotransferase returned to normal in 22 patients (71%), and hepatitis C virus RNA cleared from the sera of 15 (48%).9

Another prospective study of 50 patients treated with IFN for chronic hepatitis found that those with a pre-existing mood or anxiety disorder were not more likely than others to discontinue IFN therapy.10

Unique to hepatitis therapy? IFN-induced mood disturbances are probably different in patients with chronic hepatitis C than in those receiving IFN for other diseases because of differences in regimens and effects of the underlying pathologies. For example, prescribing a preventative antidepressant before starting IFN treatment might help cancer patients but not patients with hepatitis C.11

This distinction could be particularly important when giving IFN-alpha to patients who are vulnerable to psychiatric illness with impulsive features. To emphasize this point, we describe clinical features and treatment response in patients with hepatitis C who were treated in our department.

IFN-Alpha-Induced Moods

In our prospective study of 93 patients, 30 (32%) developed IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders during the first 12 weeks of treatment.12 Contrary to previous studies focusing on depression, most of our patients had a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Twenty-four (13 women and 11 men, mean age 43) accepted referral to a psychiatrist specializing in mood disorders to characterize their symptoms.

Mood characteristics. Using DSM-IV criteria, the psychiatrist determined that IFN-alpha induced both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in many patients, and the manic/hypomanic features predominated. Five manic symptoms and three depressive symptoms were present in >50% of patients (Figure 1, Table 1).

Three patients presented with a manic episode,15 with hypomania with prevalent irritability and dysphoric features, and 6 with a mixed depressive state (major depressive episode with at least 3 hypomania symptoms).13 Four patients (17%) suffered a relapse of alcohol or cannabis abuse.

Nearly all (84%) reported paroxysmal anxiety, and all had emotional hyperreactivity that the psychiatrist described as a main symptom of a manic or mixed state.14 Most felt extremely impulsive and feared losing control. Two faced legal difficulties, and one was in prison.

The patients’ mean Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score was 16.12 (±1.6), indicating a mild to moderate depressive state. The highest-scoring items were inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, and lassitude (Figure 2).

Their mean Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale15 score was 14.33 (±1.3), indicating hypomanic or moderate manic symptoms. Hostility was by far the predominant manic symptom (mean score 3.2/4). Other manic symptom scores ranged from 0.2/4 to 2.1/4 (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Mood symptoms identified in 24 patients after 12 weeks of IFN-alpha treatment

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 2 Depressive symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 3 Manic symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12Table 1

Most-prevalent IFN-induced mood symptoms in 24 patients treated for hepatitis C

| 5 manic symptoms (% of patients) | 3 depressive symptoms (% of patients) |

| Irritability (100%) | Insomnia or hypersomnia (100%) |

| Racing thoughts (87%) | Poor appetite or weight loss (92%) |

| Distractibility (87%) | Psychomotor agitation or retardation (54%) |

| Insomnia (58%) | |

| Agitation (70%) | |

| IFN: Interferon | |

| Source: Reference 12 | |

Treatment. Given the predominance of manic/hypomanic symptoms, we treated the 24 patients with low-to-moderate dosages of an atypical antipsychotic (amisulpride, 100 to 600 mg/d). This medication—not available in the United States—would be similar to using risperidone, 1 to 6 mg/d. Low-dose benzodiazepines (clonazepam or alprazolam) were added as needed to manage insomnia. Antipsychotic treatment enabled 23 of 24 patients (96%) to continue antiviral therapy.

Five patients had received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for 1 to 4 weeks before referral to the psychiatrist. Antidepressants worsened their mood symptoms, which included impulsivity, agitation, and insomnia. Emotional hyper-reactivity, irritability, hostility, and impulsiveness improved in all 5 patients within 1 to 2 weeks of stopping SSRIs and starting the atypical antipsychotic.

Discussion

Accurately characterizing IFN-induced mood states confirmed our published data showing a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients treated for chronic hepatitis C. Irritability and hostility were the two most prominent symptoms.

These findings differ from those of investigations that identified depressive symptoms as the hallmark of IFN’s psychiatric side effects.6 Our data were thoroughly characterized according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, two mood-rating scales, and a psychiatrist experienced in mood disorders.

Why is mania missed? One possible explanation for these different findings is that IFN-alpha-induced fatigue and flu-like symptoms could be misinterpreted as depressive symptoms. Also, most researchers have used depression rating scales—but not mania scales—and have not considered other psychiatric diagnostics.16

Self-report questionnaires for evaluating depression also take into account somatic side effects, resulting in higher rating scores. Moreover, few studies have included clinical psychiatric interviews and even fewer diagnostic confirmation by a psychiatrist.

Finally, clinical experience indicates that patients who present with both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms are more likely to complain about depression than about manic symptoms. Therefore, clinicians may miss manic symptoms if they don’t actively seek them.

Irritability and hostility. Previous studies have described irritability, mood lability, and anger/hostility as frequent symptoms4,5 but failed to consider them as possible manifestations of mania or hypomania. Many of our patients reported irritability severe enough to interfere with their work, social, and family relationships.

Hostility was the symptom with the highest score on the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale. This objective evidence suggests that investigating the consequences to patients of increased irritability, impulsivity, or hostility might reveal some frightening behavior

How to treat these patients. Considerable evidence from characterizing IFN-induced side effects in patients with hepatitis C points to a syndrome of depressive and manic/hypomanic symptoms13,17-19 that does not fulfill criteria for a mixed state. This disorder is not described in DSM-IV-TR and, unfortunately, usually is misdiagnosed as a depressive state.

Antidepressants can worsen depression by causing agitation and impulsivity and can increase risk of suicide.17,18,20 By contrast, atypical antipsychotics have been shown to improve bipolar depression.21,22

We used an atypical antipsychotic to treat patients with prevalent manic or hypomanic symptoms and those who did not respond to SSRIs. Their IFN-induced mood disorders improved rapidly on low dosages of amisulpride, and antiviral therapy discontinuation rates were low (1/24; 4%). By comparison, other studies have reported antiviral treatment discontinuation rates of 30% to 40% in patients taking antidepressants.23,24

The atypical antipsychotic did not improve our patients’ fatigue and other neurovegetative symptoms, but antidepressants likewise do not improve these symptoms.8

Recommendations

This study leads us to warn clinicians that antidepressants can worsen IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders and to recommend that antipsychotics be considered:

- at least before you decide to discontinue a hepatitis C patient’s IFN-alpha therapy

- or in patients with high irritability and hostility.

To determine whether to use an antidepressant or antimanic agent as first-line treatment, carefully diagnose the patient’s symptoms as a manic/hypomanic state, depressive mixed state, or depression. Successful IFN therapy requires:

- psychological support

- medication for psychiatric adverse effects

- collaboration between the psychiatrist and hepatologist.

IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders are triggered exogenously, do not correspond to typical features of any classic psychiatric disorder, and require further study. IFN-induced impulsivity and hostility also need to be better characterized, particularly as more patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders are treated for hepatitis C.

Related resources

- Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2001;345(1):41-52.

- Onyike CU, Bonner JO, Lyketsos CG, Treisman GJ. Mania during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:3.

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Amisulpride • (not available in the United States)

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted with support from the Centre d’Investigation Clinique INSERM/CHU de Bordeaux.

Pegylated interferon-alpha with ribavirin is the most effective therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection,1,2 but psychiatric patients often discontinue IFN-alpha because of its mood side effects.3 Most studies describe depressive states, although manic symptoms—irritability, aggression, anger, hostility, emotional lability, anxiety, panic attacks, and insomnia—also have been reported.4-6

To help you manage adverse mood changes and prevent IFN-alpha treatment discontinuation in patients with hepatitis C, this article:

- reviews studies of patients with a history mood disorders who were treated with IFN-alpha

- explains how to recognize and treat IFN-alpha-induced mood disturbances when antidepressants are contraindicated.

Psychiatric Patients and IFN Therapy

Chronic hepatitis C infection is common among psychiatric patients. Routine screening among 1,556 patients admitted to a U.S. public psychiatric hospital across 3 years identified 133 patients (8.5%) who were positive for hepatitis C virus.7

Patients with psychopathologic symptoms before starting IFN therapy may suffer more-severe adverse psychiatric effects during treatment than those without psychopathology.8 In fact, mood disorders were considered an absolute contraindication to IFN therapy until recently.

Now that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has recommended extending hepatitis C research and treatment to psychiatric patients, IFN-alpha-induced mental illness could become more common in clinical practice. Before the 2002 NIH consensus statement, patients with mental illness and substance use disorders—who represent >50% of candidates who need IFN therapy—were excluded from research protocols.

Safely using IFN. Some reports and studies suggest that patients with past or existing psychiatric disorders can be treated safely and effectively with IFN-alpha.

In a prospective open-label study, 29 of 31 patients with co-existing chronic hepatitis C and psychiatric illness completed 6 months of IFN therapy, 5 million units (MU) three times/week or 5 MU daily. Patients continued maintenance psychotropics during IFN treatment, and a psychiatrist monitored psychiatric symptoms.

Psychiatric illness worsened in four patients, and two discontinued IFN treatment. Serum alanine aminotransferase returned to normal in 22 patients (71%), and hepatitis C virus RNA cleared from the sera of 15 (48%).9

Another prospective study of 50 patients treated with IFN for chronic hepatitis found that those with a pre-existing mood or anxiety disorder were not more likely than others to discontinue IFN therapy.10

Unique to hepatitis therapy? IFN-induced mood disturbances are probably different in patients with chronic hepatitis C than in those receiving IFN for other diseases because of differences in regimens and effects of the underlying pathologies. For example, prescribing a preventative antidepressant before starting IFN treatment might help cancer patients but not patients with hepatitis C.11

This distinction could be particularly important when giving IFN-alpha to patients who are vulnerable to psychiatric illness with impulsive features. To emphasize this point, we describe clinical features and treatment response in patients with hepatitis C who were treated in our department.

IFN-Alpha-Induced Moods

In our prospective study of 93 patients, 30 (32%) developed IFN-alpha-induced mood disorders during the first 12 weeks of treatment.12 Contrary to previous studies focusing on depression, most of our patients had a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Twenty-four (13 women and 11 men, mean age 43) accepted referral to a psychiatrist specializing in mood disorders to characterize their symptoms.

Mood characteristics. Using DSM-IV criteria, the psychiatrist determined that IFN-alpha induced both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in many patients, and the manic/hypomanic features predominated. Five manic symptoms and three depressive symptoms were present in >50% of patients (Figure 1, Table 1).

Three patients presented with a manic episode,15 with hypomania with prevalent irritability and dysphoric features, and 6 with a mixed depressive state (major depressive episode with at least 3 hypomania symptoms).13 Four patients (17%) suffered a relapse of alcohol or cannabis abuse.

Nearly all (84%) reported paroxysmal anxiety, and all had emotional hyperreactivity that the psychiatrist described as a main symptom of a manic or mixed state.14 Most felt extremely impulsive and feared losing control. Two faced legal difficulties, and one was in prison.

The patients’ mean Montgomery-Åsburg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score was 16.12 (±1.6), indicating a mild to moderate depressive state. The highest-scoring items were inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, and lassitude (Figure 2).

Their mean Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale15 score was 14.33 (±1.3), indicating hypomanic or moderate manic symptoms. Hostility was by far the predominant manic symptom (mean score 3.2/4). Other manic symptom scores ranged from 0.2/4 to 2.1/4 (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Mood symptoms identified in 24 patients after 12 weeks of IFN-alpha treatment

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 2 Depressive symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12

Figure 3 Manic symptoms in 24 patients with IFN-induced mood disorder

IFN: Interferon

Source: Reference 12Table 1

Most-prevalent IFN-induced mood symptoms in 24 patients treated for hepatitis C

| 5 manic symptoms (% of patients) | 3 depressive symptoms (% of patients) |

| Irritability (100%) | Insomnia or hypersomnia (100%) |

| Racing thoughts (87%) | Poor appetite or weight loss (92%) |

| Distractibility (87%) | Psychomotor agitation or retardation (54%) |

| Insomnia (58%) | |

| Agitation (70%) | |

| IFN: Interferon | |

| Source: Reference 12 | |

Treatment. Given the predominance of manic/hypomanic symptoms, we treated the 24 patients with low-to-moderate dosages of an atypical antipsychotic (amisulpride, 100 to 600 mg/d). This medication—not available in the United States—would be similar to using risperidone, 1 to 6 mg/d. Low-dose benzodiazepines (clonazepam or alprazolam) were added as needed to manage insomnia. Antipsychotic treatment enabled 23 of 24 patients (96%) to continue antiviral therapy.

Five patients had received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for 1 to 4 weeks before referral to the psychiatrist. Antidepressants worsened their mood symptoms, which included impulsivity, agitation, and insomnia. Emotional hyper-reactivity, irritability, hostility, and impulsiveness improved in all 5 patients within 1 to 2 weeks of stopping SSRIs and starting the atypical antipsychotic.

Discussion

Accurately characterizing IFN-induced mood states confirmed our published data showing a mix of manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients treated for chronic hepatitis C. Irritability and hostility were the two most prominent symptoms.

These findings differ from those of investigations that identified depressive symptoms as the hallmark of IFN’s psychiatric side effects.6 Our data were thoroughly characterized according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, two mood-rating scales, and a psychiatrist experienced in mood disorders.

Why is mania missed? One possible explanation for these different findings is that IFN-alpha-induced fatigue and flu-like symptoms could be misinterpreted as depressive symptoms. Also, most researchers have used depression rating scales—but not mania scales—and have not considered other psychiatric diagnostics.16

Self-report questionnaires for evaluating depression also take into account somatic side effects, resulting in higher rating scores. Moreover, few studies have included clinical psychiatric interviews and even fewer diagnostic confirmation by a psychiatrist.

Finally, clinical experience indicates that patients who present with both manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms are more likely to complain about depression than about manic symptoms. Therefore, clinicians may miss manic symptoms if they don’t actively seek them.

Irritability and hostility. Previous studies have described irritability, mood lability, and anger/hostility as frequent symptoms4,5 but failed to consider them as possible manifestations of mania or hypomania. Many of our patients reported irritability severe enough to interfere with their work, social, and family relationships.