User login

When Should Hospitalists Order Continuous Cardiac Monitoring?

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

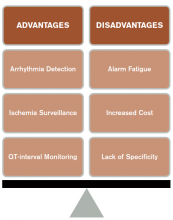

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

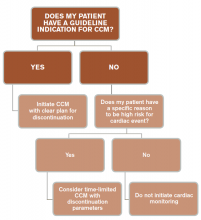

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

ED Lung Ultrasound Useful for Differentiating Cardiogenic from Noncardiogenic Dyspnea

Clinical question: Is lung ultrasound a useful tool for helping to diagnose acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: Lung ultrasound is an emerging bedside tool that has been promoted to help evaluate lung water content to help clinicians differentiate ADHF from other causes of dyspnea.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study.

Setting: Seven EDs in Italy.

Synopsis: A total of 1,005 patients were enrolled in the study. Upon presentation to the ED, patients received a standard workup, including history, physical examination, EKG, and arterial blood gas sampling. Physicians were asked to render a diagnosis of ADHF or noncardiogenic dyspnea. The same physician then performed a lung ultrasound and rendered a revised diagnosis based on the ultrasound findings. A second ED physician and cardiologist, blinded to the ultrasound results, reviewed the medical record and rendered a final diagnosis as to the cause of the patient’s dyspnea.

The ultrasound approach had a higher accuracy than clinical evaluation alone in differentiating ADHF from noncardiac causes of dyspnea (97% vs. 85.3%). The authors also report a higher sensitivity compared to chest X-ray alone (69.5%) and natriuretic peptide testing (85%).

Bottom line: Lung ultrasound combined with clinical evaluation may improve the accuracy of ADHF diagnosis, but its usefulness may be limited by the need for ED physicians to have some degree of expertise in the use of ultrasound.

Citation: Pivetta E, Goffi A, Lupia E, et al. Lung ultrasound-implemented diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in the ED: a SIMEU multicenter study. Chest. 2015;148(1):202-210.

Clinical question: Is lung ultrasound a useful tool for helping to diagnose acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: Lung ultrasound is an emerging bedside tool that has been promoted to help evaluate lung water content to help clinicians differentiate ADHF from other causes of dyspnea.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study.

Setting: Seven EDs in Italy.

Synopsis: A total of 1,005 patients were enrolled in the study. Upon presentation to the ED, patients received a standard workup, including history, physical examination, EKG, and arterial blood gas sampling. Physicians were asked to render a diagnosis of ADHF or noncardiogenic dyspnea. The same physician then performed a lung ultrasound and rendered a revised diagnosis based on the ultrasound findings. A second ED physician and cardiologist, blinded to the ultrasound results, reviewed the medical record and rendered a final diagnosis as to the cause of the patient’s dyspnea.

The ultrasound approach had a higher accuracy than clinical evaluation alone in differentiating ADHF from noncardiac causes of dyspnea (97% vs. 85.3%). The authors also report a higher sensitivity compared to chest X-ray alone (69.5%) and natriuretic peptide testing (85%).

Bottom line: Lung ultrasound combined with clinical evaluation may improve the accuracy of ADHF diagnosis, but its usefulness may be limited by the need for ED physicians to have some degree of expertise in the use of ultrasound.

Citation: Pivetta E, Goffi A, Lupia E, et al. Lung ultrasound-implemented diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in the ED: a SIMEU multicenter study. Chest. 2015;148(1):202-210.

Clinical question: Is lung ultrasound a useful tool for helping to diagnose acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: Lung ultrasound is an emerging bedside tool that has been promoted to help evaluate lung water content to help clinicians differentiate ADHF from other causes of dyspnea.

Study design: Prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study.

Setting: Seven EDs in Italy.

Synopsis: A total of 1,005 patients were enrolled in the study. Upon presentation to the ED, patients received a standard workup, including history, physical examination, EKG, and arterial blood gas sampling. Physicians were asked to render a diagnosis of ADHF or noncardiogenic dyspnea. The same physician then performed a lung ultrasound and rendered a revised diagnosis based on the ultrasound findings. A second ED physician and cardiologist, blinded to the ultrasound results, reviewed the medical record and rendered a final diagnosis as to the cause of the patient’s dyspnea.

The ultrasound approach had a higher accuracy than clinical evaluation alone in differentiating ADHF from noncardiac causes of dyspnea (97% vs. 85.3%). The authors also report a higher sensitivity compared to chest X-ray alone (69.5%) and natriuretic peptide testing (85%).

Bottom line: Lung ultrasound combined with clinical evaluation may improve the accuracy of ADHF diagnosis, but its usefulness may be limited by the need for ED physicians to have some degree of expertise in the use of ultrasound.

Citation: Pivetta E, Goffi A, Lupia E, et al. Lung ultrasound-implemented diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in the ED: a SIMEU multicenter study. Chest. 2015;148(1):202-210.

Coronary CT Angiography, Perfusion Imaging Effective for Evaluating Patients With Chest Pain

Clinical question: When evaluating the intermediate-risk patient with chest pain, should coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) be used instead of myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI)?

Background: CCTA has been shown in prior randomized controlled trials to save time and money compared to other protocols, including stress ECG, echocardiogram, and MPI. Less information is available as to whether CCTA provides a better selection of patients for cardiac catheterization compared to MPI.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial.

Setting: Telemetry ward of an urban medical center.

Synopsis: Four hundred patients admitted with chest pain and an intermediate, pre-test probability of coronary artery disease were randomized to either CCTA or MPI. Patients were predominantly female, were ethnically varied, and had a mean age of 57 years.

Study results showed no significant difference in rates of cardiac catheterization that did not lead to revascularization at one-year follow-up. Specifically, 7.5% of patients in the CCTA group underwent catheterization not leading to revascularization, compared to 10% in the MPI group.

One limitation of the study is that it was conducted at a single site. Furthermore, the decision to proceed to catheterization was made clinically and not based on a predefined algorithm.

Bottom line: CCTA and MPI are both acceptable choices to determine the need for invasive testing in patients admitted with chest pain.

Citation: Levsky JM, Spevack DM, Travin MI, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography versus radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with chest pain admitted to telemetry: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):174-183.

Clinical question: When evaluating the intermediate-risk patient with chest pain, should coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) be used instead of myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI)?

Background: CCTA has been shown in prior randomized controlled trials to save time and money compared to other protocols, including stress ECG, echocardiogram, and MPI. Less information is available as to whether CCTA provides a better selection of patients for cardiac catheterization compared to MPI.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial.

Setting: Telemetry ward of an urban medical center.

Synopsis: Four hundred patients admitted with chest pain and an intermediate, pre-test probability of coronary artery disease were randomized to either CCTA or MPI. Patients were predominantly female, were ethnically varied, and had a mean age of 57 years.

Study results showed no significant difference in rates of cardiac catheterization that did not lead to revascularization at one-year follow-up. Specifically, 7.5% of patients in the CCTA group underwent catheterization not leading to revascularization, compared to 10% in the MPI group.

One limitation of the study is that it was conducted at a single site. Furthermore, the decision to proceed to catheterization was made clinically and not based on a predefined algorithm.

Bottom line: CCTA and MPI are both acceptable choices to determine the need for invasive testing in patients admitted with chest pain.

Citation: Levsky JM, Spevack DM, Travin MI, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography versus radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with chest pain admitted to telemetry: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):174-183.

Clinical question: When evaluating the intermediate-risk patient with chest pain, should coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) be used instead of myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI)?

Background: CCTA has been shown in prior randomized controlled trials to save time and money compared to other protocols, including stress ECG, echocardiogram, and MPI. Less information is available as to whether CCTA provides a better selection of patients for cardiac catheterization compared to MPI.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial.

Setting: Telemetry ward of an urban medical center.

Synopsis: Four hundred patients admitted with chest pain and an intermediate, pre-test probability of coronary artery disease were randomized to either CCTA or MPI. Patients were predominantly female, were ethnically varied, and had a mean age of 57 years.

Study results showed no significant difference in rates of cardiac catheterization that did not lead to revascularization at one-year follow-up. Specifically, 7.5% of patients in the CCTA group underwent catheterization not leading to revascularization, compared to 10% in the MPI group.

One limitation of the study is that it was conducted at a single site. Furthermore, the decision to proceed to catheterization was made clinically and not based on a predefined algorithm.

Bottom line: CCTA and MPI are both acceptable choices to determine the need for invasive testing in patients admitted with chest pain.

Citation: Levsky JM, Spevack DM, Travin MI, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography versus radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with chest pain admitted to telemetry: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):174-183.

Can Low-Risk Patients with VTE Be Discharged from ED on Rivaroxabon?

Clinical question: Can a low-risk patient newly diagnosed with VTE in the ED be immediately discharged home on a direct factor Xa inhibitor?

Background: Studies have shown that rivaroxaban incurs a risk of 2.1% in VTE recurrence and of 9.4% in clinically relevant major and non-major bleeding (in an average 208 days follow-up). More information is required to determine if similar success can be achieved by discharging low-risk patients from the ED.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: EDs at two urban, teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: After fulfilling the criteria for low risk, 106 patients were discharged from the ED with DVT, pulmonary embolism (PE), or both. Most patients were 50 years or younger and had unprovoked VTE. Three of the 106 patients had recurrence of VTE (2.8%, 95% CI=0.6% to 8%) at a mean duration of 389 days. No patient had a major bleeding event.

In this small study, fewer than 80% of patients discharged had at least one clinic follow-up; the majority of these patients (75%) followed up in a clinic staffed by ED physicians. Therefore, ability for close follow-up must be taken into consideration prior to discharge from the ED.

Moreover, one to two days post-discharge, a member of the care team called the patient to confirm their ability to fill the rivaroxaban prescription and to answer other questions related to the new diagnosis.

Bottom line: With close follow-up and confirmation of the ability to fill a rivaroxaban prescription, patients with low-risk VTE may be discharged home from the ED.

Citation: Beam DM, Kahler ZP, Kline JA. Immediate discharge and home treatment with rivaroxaban of low-risk venous thromboembolism diagnosed in two U.S. emergency departments: a one-year preplanned analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):788-795.

Clinical question: Can a low-risk patient newly diagnosed with VTE in the ED be immediately discharged home on a direct factor Xa inhibitor?

Background: Studies have shown that rivaroxaban incurs a risk of 2.1% in VTE recurrence and of 9.4% in clinically relevant major and non-major bleeding (in an average 208 days follow-up). More information is required to determine if similar success can be achieved by discharging low-risk patients from the ED.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: EDs at two urban, teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: After fulfilling the criteria for low risk, 106 patients were discharged from the ED with DVT, pulmonary embolism (PE), or both. Most patients were 50 years or younger and had unprovoked VTE. Three of the 106 patients had recurrence of VTE (2.8%, 95% CI=0.6% to 8%) at a mean duration of 389 days. No patient had a major bleeding event.

In this small study, fewer than 80% of patients discharged had at least one clinic follow-up; the majority of these patients (75%) followed up in a clinic staffed by ED physicians. Therefore, ability for close follow-up must be taken into consideration prior to discharge from the ED.

Moreover, one to two days post-discharge, a member of the care team called the patient to confirm their ability to fill the rivaroxaban prescription and to answer other questions related to the new diagnosis.

Bottom line: With close follow-up and confirmation of the ability to fill a rivaroxaban prescription, patients with low-risk VTE may be discharged home from the ED.

Citation: Beam DM, Kahler ZP, Kline JA. Immediate discharge and home treatment with rivaroxaban of low-risk venous thromboembolism diagnosed in two U.S. emergency departments: a one-year preplanned analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):788-795.

Clinical question: Can a low-risk patient newly diagnosed with VTE in the ED be immediately discharged home on a direct factor Xa inhibitor?

Background: Studies have shown that rivaroxaban incurs a risk of 2.1% in VTE recurrence and of 9.4% in clinically relevant major and non-major bleeding (in an average 208 days follow-up). More information is required to determine if similar success can be achieved by discharging low-risk patients from the ED.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: EDs at two urban, teaching hospitals.

Synopsis: After fulfilling the criteria for low risk, 106 patients were discharged from the ED with DVT, pulmonary embolism (PE), or both. Most patients were 50 years or younger and had unprovoked VTE. Three of the 106 patients had recurrence of VTE (2.8%, 95% CI=0.6% to 8%) at a mean duration of 389 days. No patient had a major bleeding event.

In this small study, fewer than 80% of patients discharged had at least one clinic follow-up; the majority of these patients (75%) followed up in a clinic staffed by ED physicians. Therefore, ability for close follow-up must be taken into consideration prior to discharge from the ED.

Moreover, one to two days post-discharge, a member of the care team called the patient to confirm their ability to fill the rivaroxaban prescription and to answer other questions related to the new diagnosis.

Bottom line: With close follow-up and confirmation of the ability to fill a rivaroxaban prescription, patients with low-risk VTE may be discharged home from the ED.

Citation: Beam DM, Kahler ZP, Kline JA. Immediate discharge and home treatment with rivaroxaban of low-risk venous thromboembolism diagnosed in two U.S. emergency departments: a one-year preplanned analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):788-795.

Clinical Care Pathway for Cellulitis Can Help Reduce Antibiotic Use, Cost

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Clinical question: How would an evidence-based clinical pathway for cellulitis affect process metrics, patient outcomes, and clinical cost?

Background: Cellulitis is a common hospital problem, but its evaluation and treatment vary widely. Specifically, broad-spectrum antibiotics and imaging studies are overutilized when compared to recommended guidelines. A standardized clinical pathway is proposed as a possible solution.

Study design: Retrospective, observational, pre-/post-intervention study.

Setting: University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team created a guideline-based care pathway for cellulitis and enrolled 677 adult patients for retrospective analysis during a two-year period. The study showed an overall 59% decrease in the odds of ordering broad-spectrum antibiotics, 23% decrease in pharmacy cost, 44% decrease in laboratory cost, and 13% decrease in overall facility cost, pre-/post-intervention. It also demonstrated no adverse effect on length of stay or 30-day readmission rates.

Given the retrospective, single-center nature of this study, as well as some baseline characteristic differences between enrolled patients, careful conclusions regarding external validity on diverse patient populations must be considered; however, the history of clinical care pathways supports many of the study’s findings. The results make a compelling case for hospitalist groups to implement similar cellulitis pathways and research their effectiveness.

Bottom line: Clinical care pathways for cellulitis provide an opportunity to improve antibiotic stewardship and lower hospital costs without compromising quality of care.

Citation: Yarbrough PM, Kukhareva PV, Spivak ES, Hopkins C, Kawamoto K. Evidence-based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes [published online ahead of print July 28, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2433.

Antimicrobial Stewardship Resources Often Lacking in Hospitalists' Routines

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

The best antibiotic stewardship programs weave improvements into the routines of hospitalists. But at the end of the day, developing and overseeing these important programs does require some level of time and money. And setting aside that time and money has been the exception rather than the rule.

According to early results from an SHM survey, nine of 123 hospitalists said that they are compensated for work on antimicrobial stewardship programs at their hospitals. That’s a mere 7%. Only 10 out of 122 respondents said they have “protected time” for work on an antimicrobial stewardship program. That’s about 8%. And it’s possible that the survey results are actually skewed somewhat, receiving responses from more proactive centers. One hundred fifteen out of 178 respondents, or 65%, said that they have an antimicrobial stewardship program at their centers.

Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s associate director for healthcare-associated infection prevention programs, says he has found that typically about half of U.S. hospitals have such programs. Eric Howell, MD, SFHM, director of the collaborative inpatient medicine service at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, says change can be a slow process, but he expects initiatives like SHM’s new antibiotic stewardship campaign to help tip the scales toward more resources and more change. It’s a matter of “making the case that, No. 1, this is a problem and, No. 2, there are solutions out there and, No. 3, these solutions are cost effective, as well as improving quality.” Demonstrating the effects on cost and outcomes, he says, is “likely the tipping point [where] we will see real change.”

“If we don’t change, we’re going to run out of antibiotics,” says Dr. Howell, who is also senior physician advisor to SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement. “People are sort of really panic-stricken. And that fear is helping to motivate them to drive change, too.”

Jonathan Zenilman, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Bayview, says that his team worked with a non-Hopkins hospital in Delaware and found they saved about $80,000 a year just by eliminating the use of ertapenem for pre-operative prophylaxis for abdominal surgery. Numbers like that, he says, show that the case for savings can be made to hospital administration. Then again, it’s often easier to make the case before a program is started—and harder to keep it going after that first year.

“Between the second and the third year, you’re not going to generate much savings, if anything,” he says. If a new administrator is in place, it can be a challenge to get them to realize that costs will go back up once a program is dismantled.

“They look at this as an additional business model,” Dr. Zenilman explains. “They’ll say, ‘Where does my revenue offset the costs?’ And sometimes they just don’t get the value proposition…It needs to be pitched as a value proposition and not as a revenue proposition.”

The culture change toward value in the U.S. is helping, though, he says. “Now the business case is easier,” he says, “because there’s clearly this regulatory push towards doing it.” TH

Chemotherapy Does Not Improve Quality of Life with End-Stage Cancer

Clinical question: Does palliative chemotherapy improve quality of life (QOL) in patients with end-stage cancer, regardless of performance status?

Background: There is continued debate about the benefit of palliative chemotherapy at the end of life. Guidelines recommend a good performance score as an indicator of appropriate use of therapy; however, little is known about the benefits and harms of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer patients stratified by performance status.

Study design: Longitudinal, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-institutional in the United States.

Synopsis: Five U.S. institutions enrolled 661 patients with metastatic cancer and estimated life expectancy less than six months; 312 patients who died during the study period were included in the final analysis of postmortem questionnaires of caretakers regarding QOL in the patients’ last week of life. Contrary to current thought, the study demonstrated that patients undergoing end-of-life palliative chemotherapy with good ECOG performance status (0-1) had significantly worse QOL than those avoiding palliative chemotherapy. There was no difference in QOL in patients with worse performance status (ECOG 2-3).

This study is one of the first prospective investigations of this topic and makes a compelling case for withholding palliative chemotherapy at the end of life regardless of performance status. The study is somewhat limited in that the QOL measurement is only for the last week of life and the patients were not randomized into the chemotherapy arm, which could bias results.

Bottom line: Palliative chemotherapy does not improve QOL near death, and may actually worsen QOL in patients with good performance status.

Citation: Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA, et al. Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):778-784.

Clinical question: Does palliative chemotherapy improve quality of life (QOL) in patients with end-stage cancer, regardless of performance status?

Background: There is continued debate about the benefit of palliative chemotherapy at the end of life. Guidelines recommend a good performance score as an indicator of appropriate use of therapy; however, little is known about the benefits and harms of chemotherapy in metastatic cancer patients stratified by performance status.

Study design: Longitudinal, prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-institutional in the United States.

Synopsis: Five U.S. institutions enrolled 661 patients with metastatic cancer and estimated life expectancy less than six months; 312 patients who died during the study period were included in the final analysis of postmortem questionnaires of caretakers regarding QOL in the patients’ last week of life. Contrary to current thought, the study demonstrated that patients undergoing end-of-life palliative chemotherapy with good ECOG performance status (0-1) had significantly worse QOL than those avoiding palliative chemotherapy. There was no difference in QOL in patients with worse performance status (ECOG 2-3).

This study is one of the first prospective investigations of this topic and makes a compelling case for withholding palliative chemotherapy at the end of life regardless of performance status. The study is somewhat limited in that the QOL measurement is only for the last week of life and the patients were not randomized into the chemotherapy arm, which could bias results.