User login

Procalcitonin Testing Can Lead to Cost Savings

Clinical question: Can procalcitonin testing be used to determine whether antibiotics should be started and stopped?

Background: Procalcitonin naturally occurs in the body but increases with bacterial infection, with normal levels

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: ICUs and EDs in Europe, China, and Brazil.

Synopsis: A systematic review of eight RCTs in the ICU showed that, in adults, procalcitonin testing decreased antibiotic duration (weighted mean difference [WMD] -3.2 days; 95% CI, -5.44 to -0.95), decreased hospital length of stay (WMD -3.85 days; 95% CI, -6.78 to -0.92), and trended toward decreased ICU length of stay (WMD -2.03 days; 95% CI, -4.19 to 0.13).

Further review of eight different trials looking at procalcitonin testing in the ED showed that, in adults with suspected bacterial infection, procalcitonin testing reduced proportion of adults receiving antibiotics (relative risk 0.77; 95% CI, 0.68–0.87) and a trend toward reduction in hospital stays. No strong conclusions could be made about the effect on duration of antibiotic therapy. Procalcitonin testing was demonstrated to be cost-effective in the study population, saving £3,268 in adults with sepsis in the ICU.

Most studies were of unclear quality and unclear risk of bias secondary to insufficient reporting; therefore, results must be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin testing may be a cost-saving measure for adults with sepsis in the ICU and adults with possible bacterial infections in the ED.

Citation: Westwood M, Raemaekers B, Whiting P, et al. Procalcitonin testing to guide antibiotic therapy for the treatment of sepsis in intensive care settings and for suspected bacterial infection in emergency department settings: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(96):1-236.

Short Take

Adjuvant Flu Vaccine Approved for Prevention of Seasonal Influenza

The FDA approved Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent vaccine, for the prevention of seasonal influenza in patients >65 years of age based on studies showing comparable safety and immunogenicity to Agriflu, a FDA-approved unadjuvanted trivalent vaccine.

Citation: FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine containing an adjuvant [news release]. Washington, DC: FDA; November 24, 2015

Clinical question: Can procalcitonin testing be used to determine whether antibiotics should be started and stopped?

Background: Procalcitonin naturally occurs in the body but increases with bacterial infection, with normal levels

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: ICUs and EDs in Europe, China, and Brazil.

Synopsis: A systematic review of eight RCTs in the ICU showed that, in adults, procalcitonin testing decreased antibiotic duration (weighted mean difference [WMD] -3.2 days; 95% CI, -5.44 to -0.95), decreased hospital length of stay (WMD -3.85 days; 95% CI, -6.78 to -0.92), and trended toward decreased ICU length of stay (WMD -2.03 days; 95% CI, -4.19 to 0.13).

Further review of eight different trials looking at procalcitonin testing in the ED showed that, in adults with suspected bacterial infection, procalcitonin testing reduced proportion of adults receiving antibiotics (relative risk 0.77; 95% CI, 0.68–0.87) and a trend toward reduction in hospital stays. No strong conclusions could be made about the effect on duration of antibiotic therapy. Procalcitonin testing was demonstrated to be cost-effective in the study population, saving £3,268 in adults with sepsis in the ICU.

Most studies were of unclear quality and unclear risk of bias secondary to insufficient reporting; therefore, results must be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin testing may be a cost-saving measure for adults with sepsis in the ICU and adults with possible bacterial infections in the ED.

Citation: Westwood M, Raemaekers B, Whiting P, et al. Procalcitonin testing to guide antibiotic therapy for the treatment of sepsis in intensive care settings and for suspected bacterial infection in emergency department settings: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(96):1-236.

Short Take

Adjuvant Flu Vaccine Approved for Prevention of Seasonal Influenza

The FDA approved Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent vaccine, for the prevention of seasonal influenza in patients >65 years of age based on studies showing comparable safety and immunogenicity to Agriflu, a FDA-approved unadjuvanted trivalent vaccine.

Citation: FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine containing an adjuvant [news release]. Washington, DC: FDA; November 24, 2015

Clinical question: Can procalcitonin testing be used to determine whether antibiotics should be started and stopped?

Background: Procalcitonin naturally occurs in the body but increases with bacterial infection, with normal levels

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: ICUs and EDs in Europe, China, and Brazil.

Synopsis: A systematic review of eight RCTs in the ICU showed that, in adults, procalcitonin testing decreased antibiotic duration (weighted mean difference [WMD] -3.2 days; 95% CI, -5.44 to -0.95), decreased hospital length of stay (WMD -3.85 days; 95% CI, -6.78 to -0.92), and trended toward decreased ICU length of stay (WMD -2.03 days; 95% CI, -4.19 to 0.13).

Further review of eight different trials looking at procalcitonin testing in the ED showed that, in adults with suspected bacterial infection, procalcitonin testing reduced proportion of adults receiving antibiotics (relative risk 0.77; 95% CI, 0.68–0.87) and a trend toward reduction in hospital stays. No strong conclusions could be made about the effect on duration of antibiotic therapy. Procalcitonin testing was demonstrated to be cost-effective in the study population, saving £3,268 in adults with sepsis in the ICU.

Most studies were of unclear quality and unclear risk of bias secondary to insufficient reporting; therefore, results must be interpreted with caution.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin testing may be a cost-saving measure for adults with sepsis in the ICU and adults with possible bacterial infections in the ED.

Citation: Westwood M, Raemaekers B, Whiting P, et al. Procalcitonin testing to guide antibiotic therapy for the treatment of sepsis in intensive care settings and for suspected bacterial infection in emergency department settings: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(96):1-236.

Short Take

Adjuvant Flu Vaccine Approved for Prevention of Seasonal Influenza

The FDA approved Fluad, an adjuvanted trivalent vaccine, for the prevention of seasonal influenza in patients >65 years of age based on studies showing comparable safety and immunogenicity to Agriflu, a FDA-approved unadjuvanted trivalent vaccine.

Citation: FDA approves first seasonal influenza vaccine containing an adjuvant [news release]. Washington, DC: FDA; November 24, 2015

New Model May Predict Risk of Acute Kidney Injury in Orthopedic Patients

Clinical question: What is the risk of acute kidney injury after orthopedic surgery, and does it impact mortality?

Background: Current studies show that acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality, future development of chronic kidney disease, and increased healthcare costs. However, no externally validated models are available to predict patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery at risk of postoperative acute kidney injury.

Study design: Observational, cohort study.

Setting: Teaching and private hospitals in the National Health Service (NHS) in the Tayside region of Scotland.

Synopsis: Investigators enrolled 10,615 adults >18 years of age undergoing orthopedic surgery into two groups: development cohort (6,220 patients) and validation cohort (4,395 patients). Using the development cohort, seven predictors were identified in the risk model: age at operation, male sex, diabetes, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, number of prescribing drugs, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade.

The model’s predictive performance for discrimination was good in the development cohort (C statistic 0.74; 95% CI, 0.72–0.76) and validation cohort (C statistic 0.7). Calibration was good in the development cohort but overestimated the risk in the validation cohort. Postoperative acute kidney injury developed in 672 (10.8%) patients in the development cohort and 295 (6.7%) in the validation cohort. Thirty percent (3,166) of the 10,615 patients enrolled in this study died over the median follow-up of 4.58 years. Survival was worse in the patients with acute kidney injury (adjusted hazard ratio 1.53; 95% CI, 1.38–1.70), worse in the short term (90-day adjusted hazard ratio 2.36; 95% CI, 1.94–2.87), and diminished over time.

Bottom line: A predictive model using age, male sex, diabetes, lower GFR, use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, multiple medications, and ASA grades might predict risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in orthopedic patients.

Citation: Bell S, Dekker FW, Vadiveloo T, et al. Risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery—development and validation of a risk score and effect of acute kidney injury on survival: observational cohort study. BMJ 2015; 351:h5639.

Clinical question: What is the risk of acute kidney injury after orthopedic surgery, and does it impact mortality?

Background: Current studies show that acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality, future development of chronic kidney disease, and increased healthcare costs. However, no externally validated models are available to predict patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery at risk of postoperative acute kidney injury.

Study design: Observational, cohort study.

Setting: Teaching and private hospitals in the National Health Service (NHS) in the Tayside region of Scotland.

Synopsis: Investigators enrolled 10,615 adults >18 years of age undergoing orthopedic surgery into two groups: development cohort (6,220 patients) and validation cohort (4,395 patients). Using the development cohort, seven predictors were identified in the risk model: age at operation, male sex, diabetes, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, number of prescribing drugs, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade.

The model’s predictive performance for discrimination was good in the development cohort (C statistic 0.74; 95% CI, 0.72–0.76) and validation cohort (C statistic 0.7). Calibration was good in the development cohort but overestimated the risk in the validation cohort. Postoperative acute kidney injury developed in 672 (10.8%) patients in the development cohort and 295 (6.7%) in the validation cohort. Thirty percent (3,166) of the 10,615 patients enrolled in this study died over the median follow-up of 4.58 years. Survival was worse in the patients with acute kidney injury (adjusted hazard ratio 1.53; 95% CI, 1.38–1.70), worse in the short term (90-day adjusted hazard ratio 2.36; 95% CI, 1.94–2.87), and diminished over time.

Bottom line: A predictive model using age, male sex, diabetes, lower GFR, use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, multiple medications, and ASA grades might predict risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in orthopedic patients.

Citation: Bell S, Dekker FW, Vadiveloo T, et al. Risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery—development and validation of a risk score and effect of acute kidney injury on survival: observational cohort study. BMJ 2015; 351:h5639.

Clinical question: What is the risk of acute kidney injury after orthopedic surgery, and does it impact mortality?

Background: Current studies show that acute kidney injury is associated with increased long-term mortality, future development of chronic kidney disease, and increased healthcare costs. However, no externally validated models are available to predict patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery at risk of postoperative acute kidney injury.

Study design: Observational, cohort study.

Setting: Teaching and private hospitals in the National Health Service (NHS) in the Tayside region of Scotland.

Synopsis: Investigators enrolled 10,615 adults >18 years of age undergoing orthopedic surgery into two groups: development cohort (6,220 patients) and validation cohort (4,395 patients). Using the development cohort, seven predictors were identified in the risk model: age at operation, male sex, diabetes, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, number of prescribing drugs, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade.

The model’s predictive performance for discrimination was good in the development cohort (C statistic 0.74; 95% CI, 0.72–0.76) and validation cohort (C statistic 0.7). Calibration was good in the development cohort but overestimated the risk in the validation cohort. Postoperative acute kidney injury developed in 672 (10.8%) patients in the development cohort and 295 (6.7%) in the validation cohort. Thirty percent (3,166) of the 10,615 patients enrolled in this study died over the median follow-up of 4.58 years. Survival was worse in the patients with acute kidney injury (adjusted hazard ratio 1.53; 95% CI, 1.38–1.70), worse in the short term (90-day adjusted hazard ratio 2.36; 95% CI, 1.94–2.87), and diminished over time.

Bottom line: A predictive model using age, male sex, diabetes, lower GFR, use of ACE inhibitor/ARB, multiple medications, and ASA grades might predict risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in orthopedic patients.

Citation: Bell S, Dekker FW, Vadiveloo T, et al. Risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery—development and validation of a risk score and effect of acute kidney injury on survival: observational cohort study. BMJ 2015; 351:h5639.

Treating Asymptomatic Bacteriuria Can Be Dangerous

Clinical question: Does treating asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB) cause harm in women?

Background: In women with recurrent UTIs, AB is often treated, increasing the risk of multi-drug-resistant bacteria. At the same time, little data exist on the relationship between AB treatment and risk of higher antibiotic resistance in women with recurrent UTIs.

Study design: Follow-up observational, analytical, longitudinal study on a previously randomized clinical trial (RCT).

Setting: Sexually transmitted disease (STD) center in Florence, Italy.

Synopsis: Using the patients from the authors’ previous RCT, the study followed 550 women with recurrent UTIs and AB for a mean of 38.8 months in parallel groups: One group had AB treated, and the other group did not. In the group of women treated with antibiotics, the recurrence rate was 69.6% versus 37.7% in the group not treated (P<0.001). In addition, E. coli isolates showed more resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (P=0.03), trimethoprim/sulfamethazole (P=0.01), and ciprofloxacin (P=0.03) in the group previously treated with antibiotics.

Given the observational design of the study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. However, prior studies have shown this relationship, and current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines support neither screening nor treating AB.

Bottom line: In women with recurrent UTIs, previous treatment of AB is associated with higher rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, causing symptomatic UTIs.

Citation: Cai T, Nsei G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661.

Short Take

National Healthcare Spending Increased in 2014

Led by expansions under the Affordable Care Act, healthcare spending increased 5.3% from the previous year and now totals $3 trillion, which represents 17.5% of the gross domestic product.

Citation: Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, Catlin A. National health spending in 2014: faster growth drive by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):150-160.

Clinical question: Does treating asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB) cause harm in women?

Background: In women with recurrent UTIs, AB is often treated, increasing the risk of multi-drug-resistant bacteria. At the same time, little data exist on the relationship between AB treatment and risk of higher antibiotic resistance in women with recurrent UTIs.

Study design: Follow-up observational, analytical, longitudinal study on a previously randomized clinical trial (RCT).

Setting: Sexually transmitted disease (STD) center in Florence, Italy.

Synopsis: Using the patients from the authors’ previous RCT, the study followed 550 women with recurrent UTIs and AB for a mean of 38.8 months in parallel groups: One group had AB treated, and the other group did not. In the group of women treated with antibiotics, the recurrence rate was 69.6% versus 37.7% in the group not treated (P<0.001). In addition, E. coli isolates showed more resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (P=0.03), trimethoprim/sulfamethazole (P=0.01), and ciprofloxacin (P=0.03) in the group previously treated with antibiotics.

Given the observational design of the study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. However, prior studies have shown this relationship, and current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines support neither screening nor treating AB.

Bottom line: In women with recurrent UTIs, previous treatment of AB is associated with higher rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, causing symptomatic UTIs.

Citation: Cai T, Nsei G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661.

Short Take

National Healthcare Spending Increased in 2014

Led by expansions under the Affordable Care Act, healthcare spending increased 5.3% from the previous year and now totals $3 trillion, which represents 17.5% of the gross domestic product.

Citation: Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, Catlin A. National health spending in 2014: faster growth drive by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):150-160.

Clinical question: Does treating asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB) cause harm in women?

Background: In women with recurrent UTIs, AB is often treated, increasing the risk of multi-drug-resistant bacteria. At the same time, little data exist on the relationship between AB treatment and risk of higher antibiotic resistance in women with recurrent UTIs.

Study design: Follow-up observational, analytical, longitudinal study on a previously randomized clinical trial (RCT).

Setting: Sexually transmitted disease (STD) center in Florence, Italy.

Synopsis: Using the patients from the authors’ previous RCT, the study followed 550 women with recurrent UTIs and AB for a mean of 38.8 months in parallel groups: One group had AB treated, and the other group did not. In the group of women treated with antibiotics, the recurrence rate was 69.6% versus 37.7% in the group not treated (P<0.001). In addition, E. coli isolates showed more resistance to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (P=0.03), trimethoprim/sulfamethazole (P=0.01), and ciprofloxacin (P=0.03) in the group previously treated with antibiotics.

Given the observational design of the study, data must be interpreted with caution in determining a causal relationship. However, prior studies have shown this relationship, and current Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines support neither screening nor treating AB.

Bottom line: In women with recurrent UTIs, previous treatment of AB is associated with higher rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, causing symptomatic UTIs.

Citation: Cai T, Nsei G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661.

Short Take

National Healthcare Spending Increased in 2014

Led by expansions under the Affordable Care Act, healthcare spending increased 5.3% from the previous year and now totals $3 trillion, which represents 17.5% of the gross domestic product.

Citation: Martin AB, Hartman M, Benson J, Catlin A. National health spending in 2014: faster growth drive by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff. 2016;35(1):150-160.

HM16 AUDIO: Alyssa Stephany, MD, Talks about the HM16 RIV Scientific Abstract Competition

Alyssa Stephany, MD, then assistant professor at Duke and now section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, talks about the evolution in training stemming from her experience in the HM16 RIV competition. This year, she oversaw a study for which resident

Jennifer Ladd, MD, won an award for pediatric clinical vignette.

Alyssa Stephany, MD, then assistant professor at Duke and now section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, talks about the evolution in training stemming from her experience in the HM16 RIV competition. This year, she oversaw a study for which resident

Jennifer Ladd, MD, won an award for pediatric clinical vignette.

Alyssa Stephany, MD, then assistant professor at Duke and now section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, talks about the evolution in training stemming from her experience in the HM16 RIV competition. This year, she oversaw a study for which resident

Jennifer Ladd, MD, won an award for pediatric clinical vignette.

HM16 AUDIO: Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, Chats up His Research on Costs and Complications with PICC Line Usage

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

Postoperative Clostridium Difficile Infection Associated with Number of Antibiotics, Surgical Procedure Complexity

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Most Postoperative Readmissions Due to Patient Factors

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

When Should Harm-Reduction Strategies Be Used for Inpatients with Opioid Misuse?

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

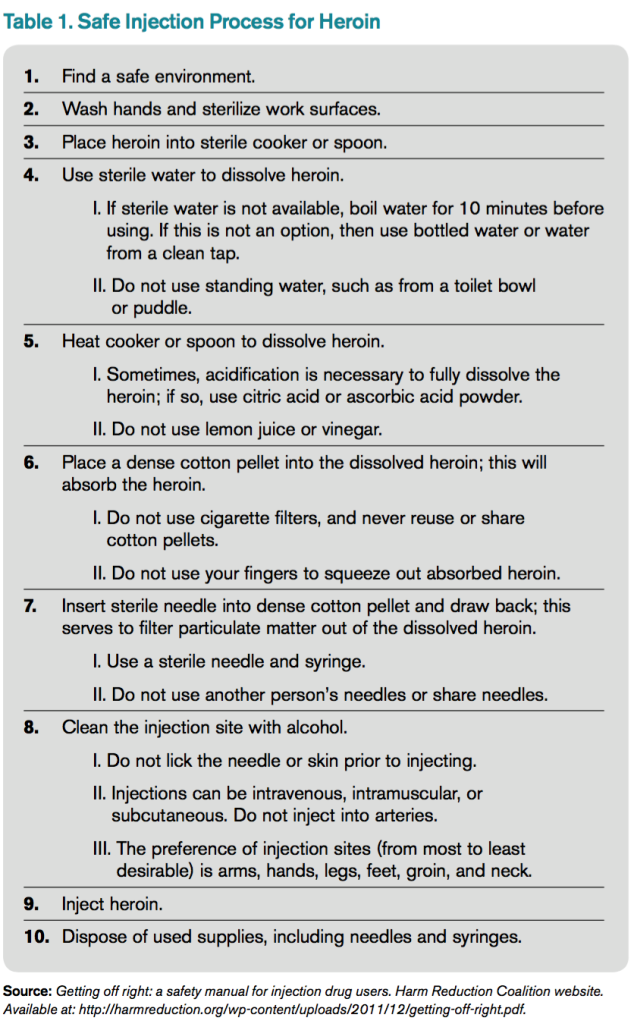

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

QUIZ: Which Strategy Should Hospitalists Employ to Reduce the Risk of Opioid Misuse?

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

Ischemic Hepatitis Associated with High Inpatient Mortality

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that music reduces pain and anxiety and decreases the need for pain medication in postoperative patients regardless of type of music or at what interval of the operative period the music was initiated.

Citation: Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1659-1671

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that music reduces pain and anxiety and decreases the need for pain medication in postoperative patients regardless of type of music or at what interval of the operative period the music was initiated.

Citation: Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1659-1671

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery