User login

Heart Failure Diagnostic Alerts to Prompt Pharmacist Evaluation and Medication Optimization

Heart Failure Diagnostic Alerts to Prompt Pharmacist Evaluation and Medication Optimization

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent disease in the United States affecting > 6.5 million adults and contributing to significant morbidity and mortality.1 The disease course associated with HF includes potential symptom improvement with intermittent periods of decompensation and possible clinical deterioration. Multiple therapies have been developed to improve outcomes in people with HF—to palliate HF symptoms, prevent hospitalizations, and reduce mortality.2 However, the risks of decompensation and hospitalization remain. HF decompensation development may precede clear actionable symptoms such as worsening dyspnea, noticeable edema, or weight gain. Tools to identify patient deterioration and trigger interventions to prevent HF admissions are clinically attractive compared with reliance on subjective factors alone.

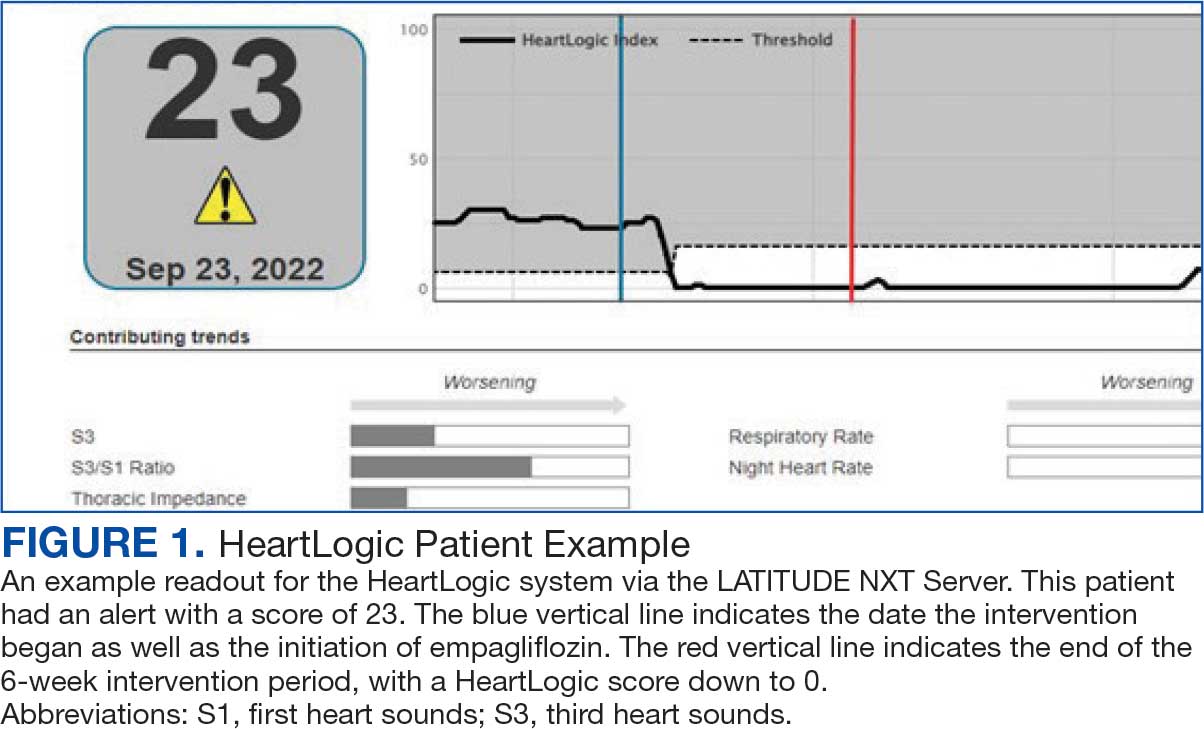

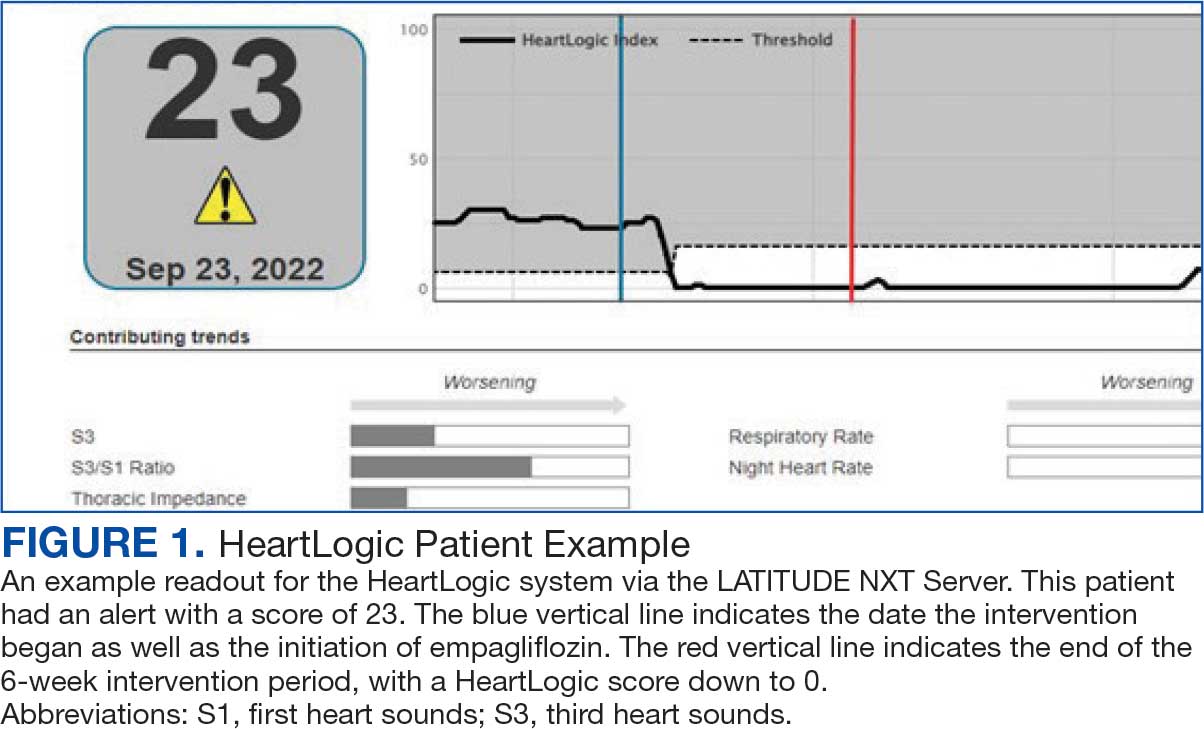

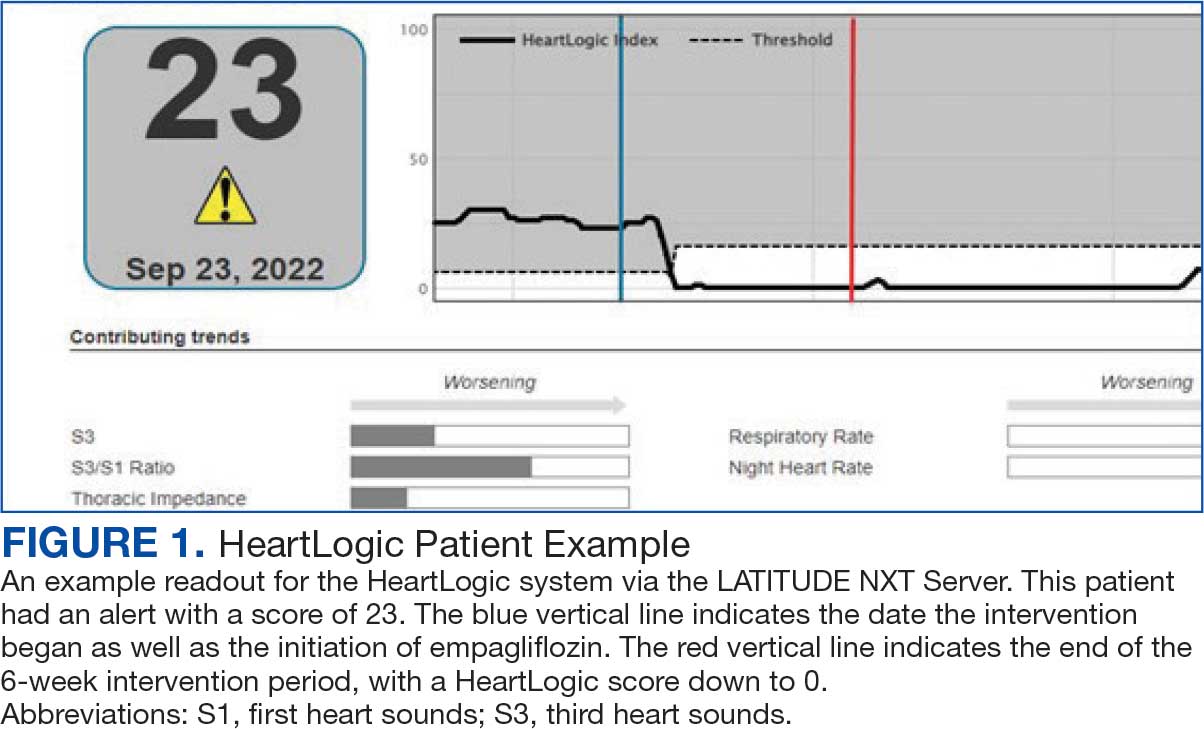

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices made by Boston Scientific include the HeartLogic monitoring feature. Five main sensors produce an index risk score; an index score > 16 warns clinicians that the patient is at an increased risk for a HF event.3 The 5 sensors are thoracic impedance, first (S1) and third heart sounds (S3), night heart rate (NHR), respiratory rate (RR), and activity. Each sensor can draw attention to the primary driver of the alert and guide health care practitioners (HCPs) to the appropriate interventions.3 A HeartLogic alert example is shown in Figure 1.

The S3 occurs during the early diastolic phase when blood moves into the ventricles. As HF worsens, with a combination of elevated filling pressures and reduced cardiac muscle compliance, S3 can become more pronounced.4 The S1 is correlated with the contractility of the left ventricle and will be reduced in patients at risk for HF events.5 Physical activity is a long-term prognostic marker in patients with HF; reduced activity is associated with mortality and increased risk of an HF event.6 Thoracic impedance is a sensor used to identify pulmonary congestion, pocket infections, pleural/pericardial effusion, and respiratory infections. The accumulation of intrathoracic fluid during pulmonary congestion increases conductance, causing a decrease in impedance.7 RR will increase as patients experience dyspnea with a more rapid, shallow breath and may trigger alerts closer to the actual HF event than other sensors. Nearly 90% of patients hospitalized for HF experience shortness of breath.8,9 NHR is used as a surrogate for resting heart rate (HR). A high resting HR is correlated with the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, harmful effects on left ventricular function, and increased risk of myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias.10

One of the challenges with preventing hospitalizations may be the lack of patient reported symptoms leading up to the event. The purpose of the sensors and HeartLogic index is to identify patients a median of 34 days before an HF event (HF admission or unscheduled intervention with intravenous treatment) with a sensitivity rate of 70%.3 According to real-word experience data, alerts have been found to precede HF symptoms by a median of 12 days and HF events such as hospitalizations by a median of 38 days, with an overall 67% reduction in HF hospitalizations when integrated into clinical care.11,12

MANAGE-HF evaluated 191 patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (< 35%), New York Heart Association class II-III symptoms, and who had an implanted CRT and/or ICD to develop an alert management guide to optimize medical treatment.12 It aimed to adjust patient regimen within 6 days of an elevated Heart- Logic index by either initiation, escalation, or maintenance of HF treatment depending on the index trend after the initial alert. This trial found that by focusing on such optimization, HF treatment was augmented during 74% of the 585 alert cases and during 54% of 3290 weekly alerts.

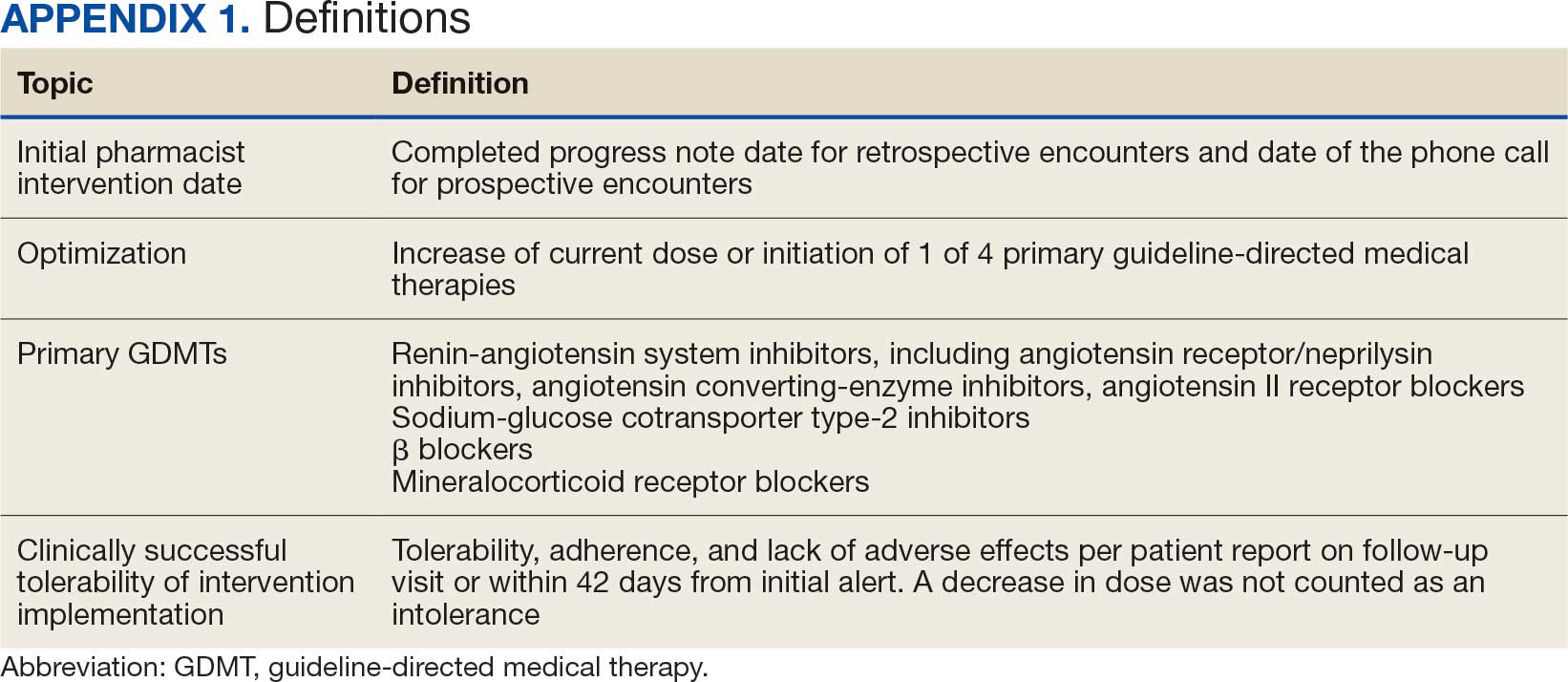

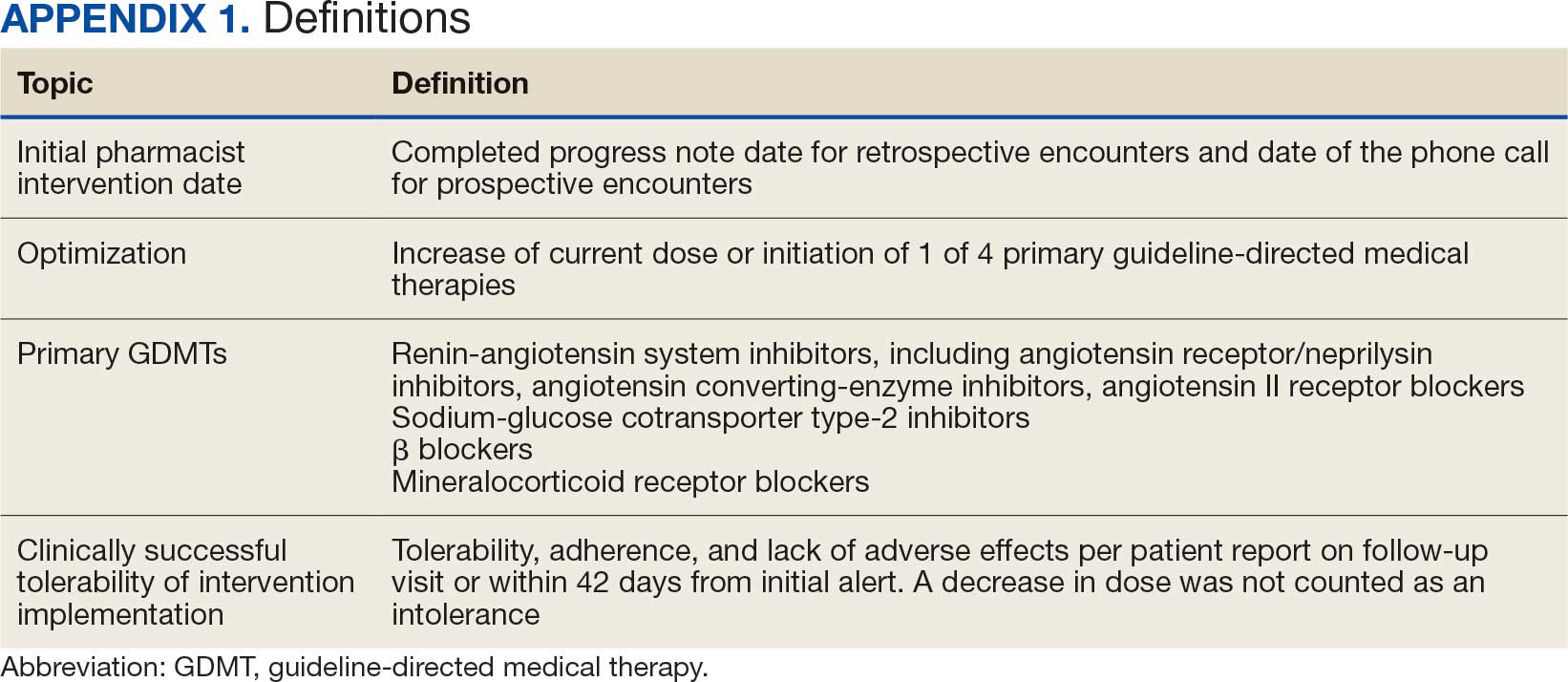

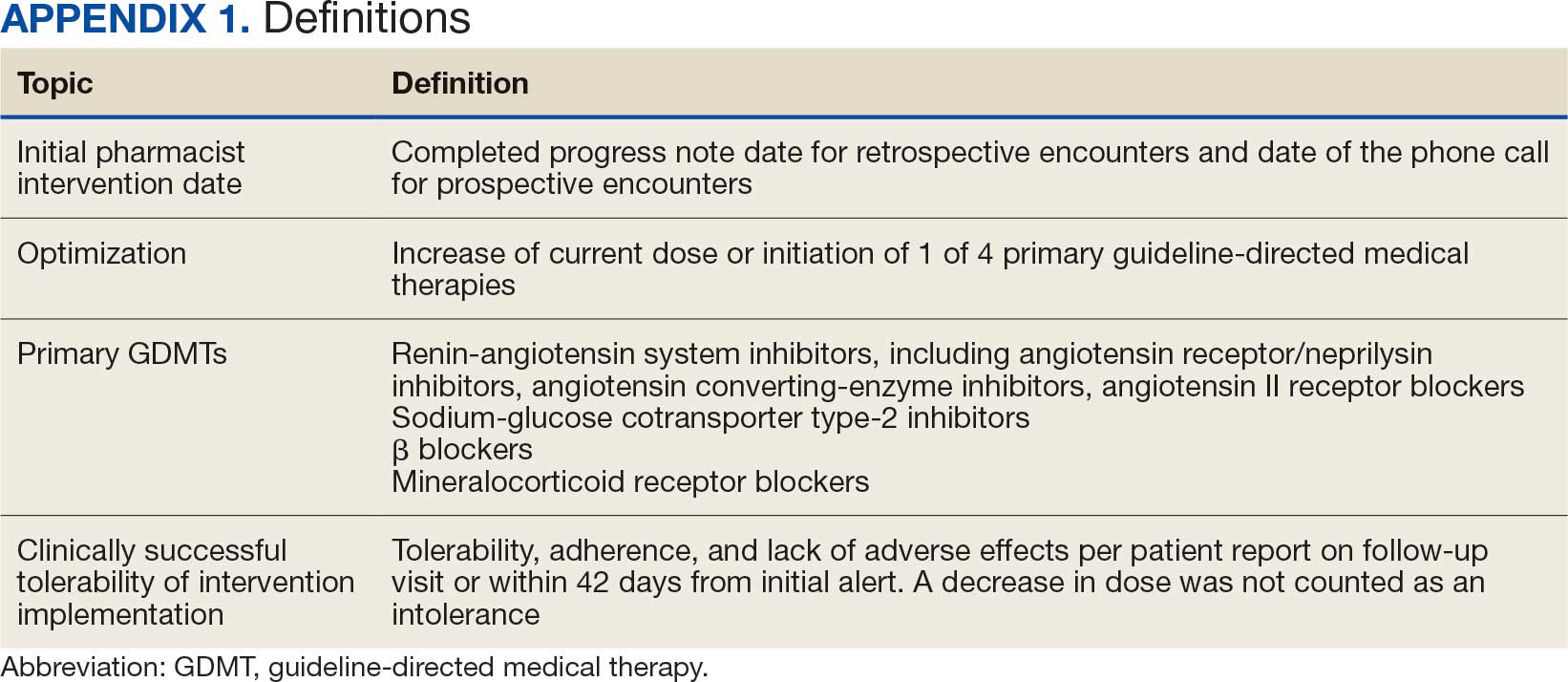

Initiation and uptitration of the 4 primary components of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) are recommended by the 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with HFrEF.2 The 4 pillars of GDMT consist of -blockers (BB), sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi) including angiotensin II receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) (Appendix 1). Obtaining and titrating to target doses wherever possible is recommended, as those were the doses that established safety and efficacy in patients with HFrEF in clinical trials.2 Pharmacists are adequately equipped to optimize HF GDMT and appropriately monitor drug response.

Through the use of HeartLogic in clinical practice, patients with HF have been shown to have improved clinical outcomes and are more likely to receive effective care; 80% of alerts were shown to provide new information to clinicians.13 This project sought to quantify the total number and types of pharmacist interventions driven by integration of HeartLogic index monitoring into practice.

Methods

The West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC) Research Program Office approved this project and determined it was exempt from institutional review board oversight. Patients were screened retrospectively and prospectively from May 26, 2022, through December 31, 2022, by a cardiology clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) and a cardiology pharmacy resident using the local monitoring suite for the HeartLogic-compatible device, LATITUDE NXT. Read-only access to the local monitoring suit was granted by the National Cardiac Device Surveillance Program. Training for HeartLogic was completed through continuing education courses provided by Boston Scientific. Additional information was provided by Boston Scientific representative presentations and collaboration with WPBVAMC pacemaker clinic HCPs.

Individuals included were patients with HeartLogic-capable ICDs. A HeartLogic alert had to be present at initial patient contact. Patients were also contacted as part of routine clinical practice, but no formal number or frequency of calls to patients was required. The initial contact must be with a pharmacist for the patient to be included, but subsequent contact by other HCPs was included. Patients in the cardiology clinic are required to meet with a cardiologist at least annually; however, interim visits can be completed by advanced practice registered nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, or CPPs.

Patients in alert status were contacted by telephone and appropriate modifications of HF therapy were made by the CPP based on score metrics, medical record review, and patient interview. Information surrounding the initial alert, baseline patient data, medication and monitoring interventions made, and clinical outcomes such as hospitalization, symptom improvement, follow-up, and mortality were collected. Information for each encounter was collected until 42 days from the initial date of pharmacist contact.

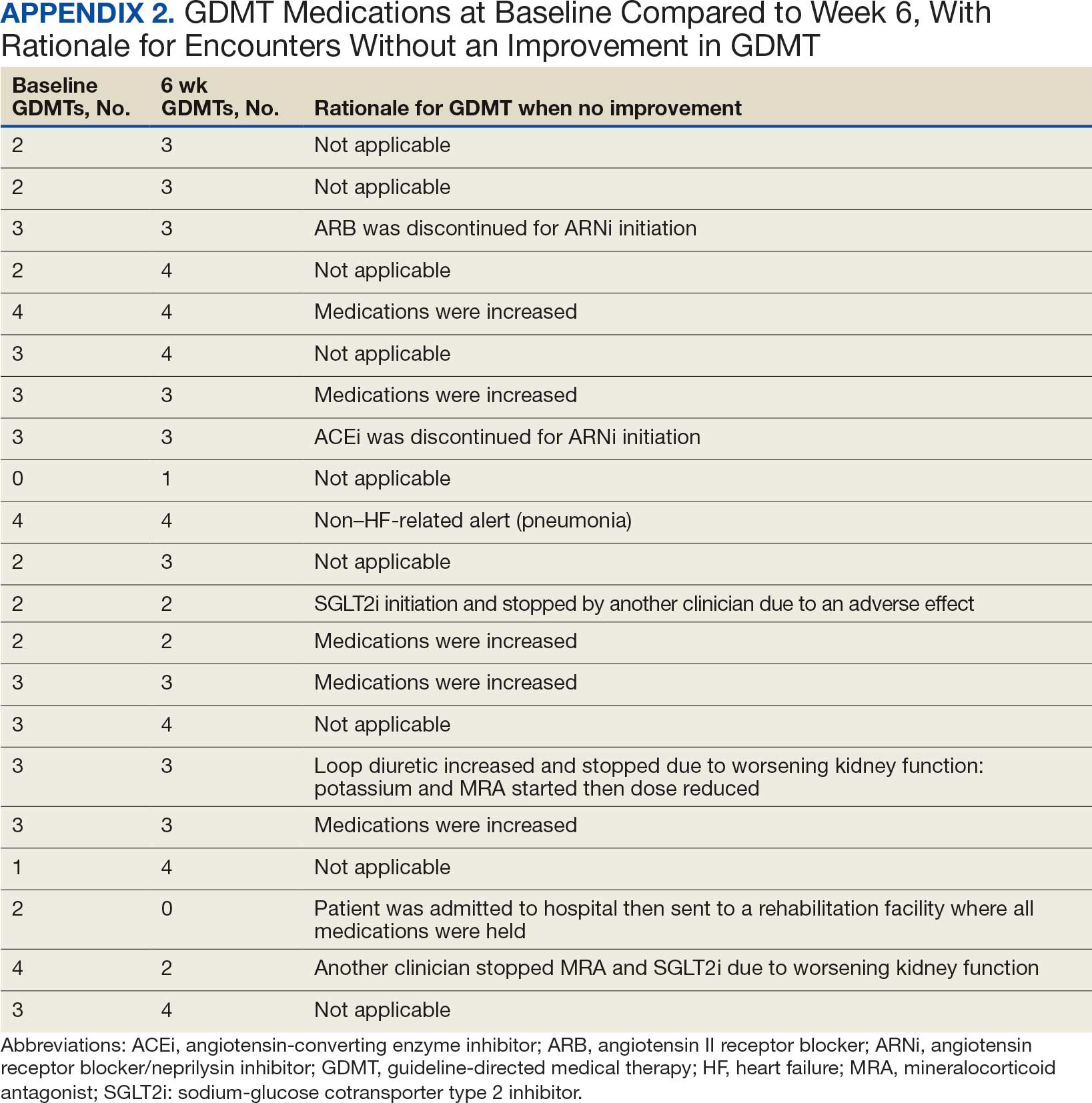

Clinically successful tolerability of intervention implementation was defined as tolerability, adherence, and lack of adverse effects (AEs) per patient report at follow-up or within 42 days from initial alert (Appendix 2). A decrease in dose was not counted as intolerance. A single patient may have been counted as multiple encounters if the original intervention resulted in treatment intolerance and the patient remained in alert or if an additional alert occurred after 42 days of the initial alert. There were no specific time criteria for follow-up, which occurred at the CPP’s discretion.

There was no mandated algorithm used to alter medications based on the Heart- Logic score, nor were there required minimum or maximum numbers of interventions after an alert. Patient contact by telephone initiated an encounter. The types of interventions included medication increases, decreases, initiation, discontinuation, or no medication change. Each medication change and rationale, if applicable, was recorded for the encounter ≤ 42 days after the initial contact date. If a medication with required monitoring parameters was augmented, the pharmacist was responsible for ordering laboratory testing and follow-up. Most interventions were completed by telephone; however, some patients had in-person visits in the HF CPP clinic.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of pharmacist interventions made to optimize GDMT, defined as either an initiation or dose increase. Key intervention analysis included the use and dosing of the 4 primary components of HF GDMT: BB, SGLT2i, MRA, and ARNi/ARB/ACEi. In addition to the 4 primary components of GDMT, loop diuretic changes were also recorded and analyzed. Secondary endpoints were the number of HF hospitalizations ≤ 42 days after the initial alert, and the effect of medication interventions on device metrics, patient symptoms, and tolerability. Successful tolerability was defined as continued use of augmented GDMT without intolerance or discontinuation. The primary analysis was analyzed through descriptive statistics. Median changes in HeartLogic scores and metrics from baseline were analyzed using a paired, 2-sided t test with an α of .05 to detect significance.

Results

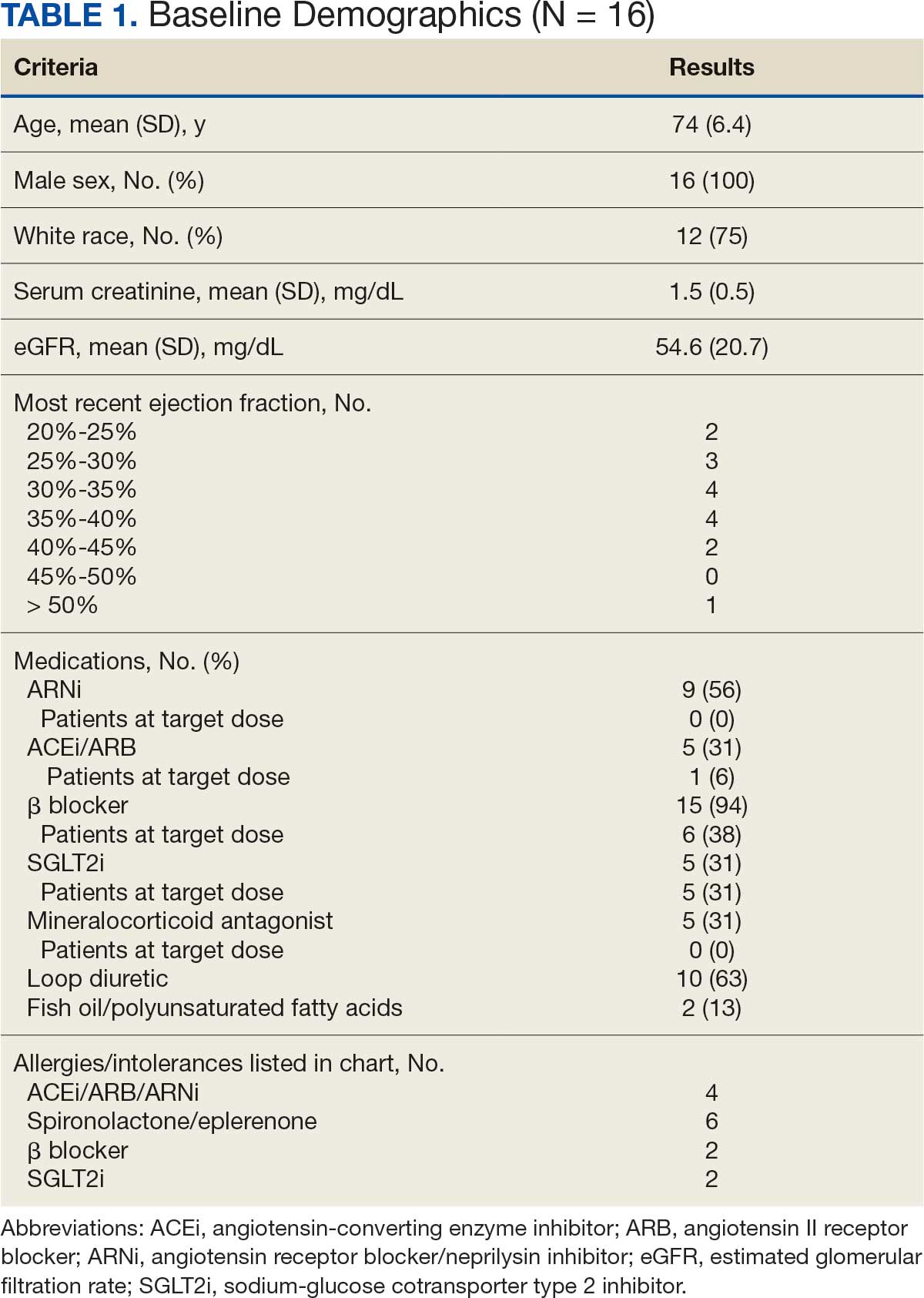

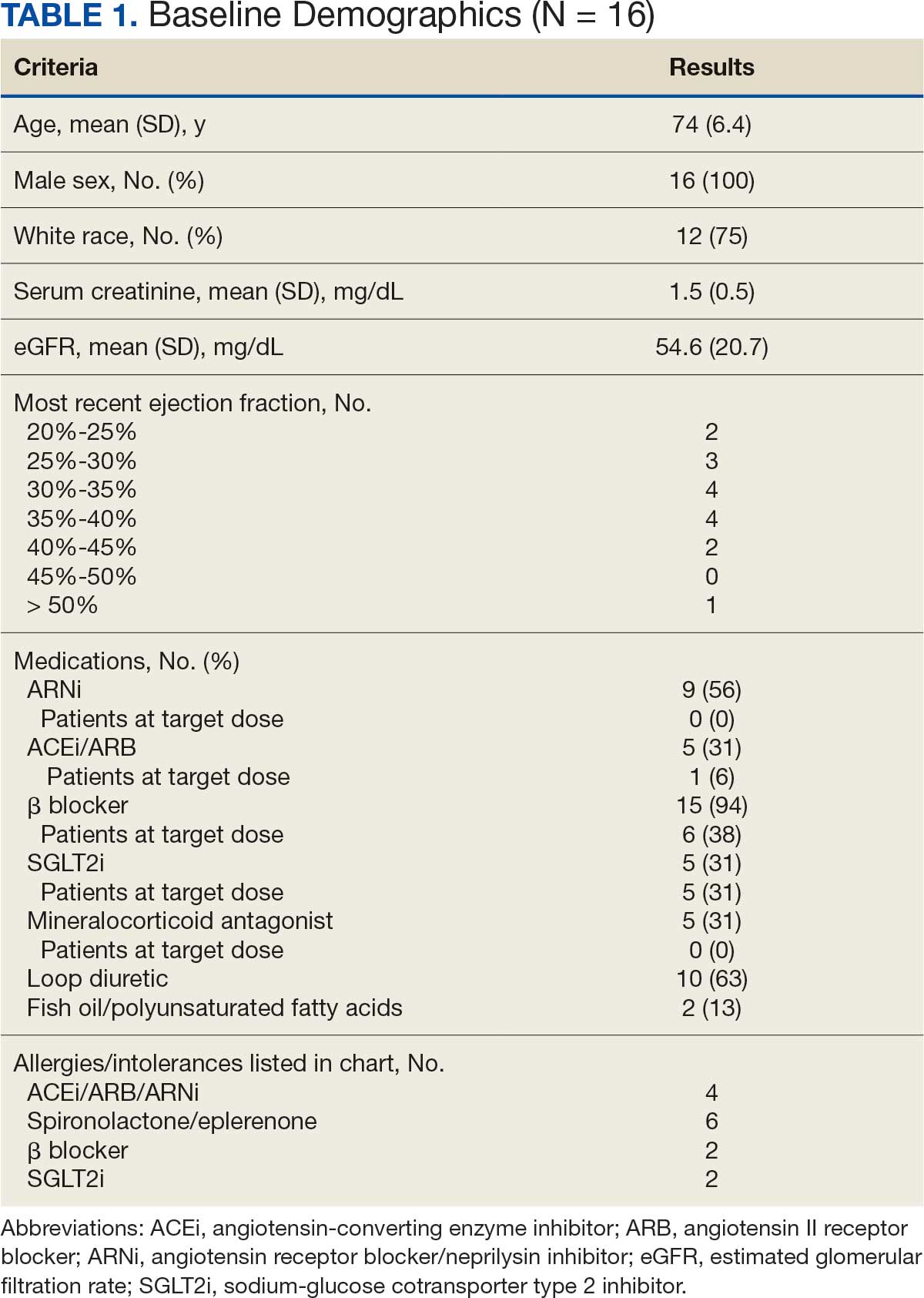

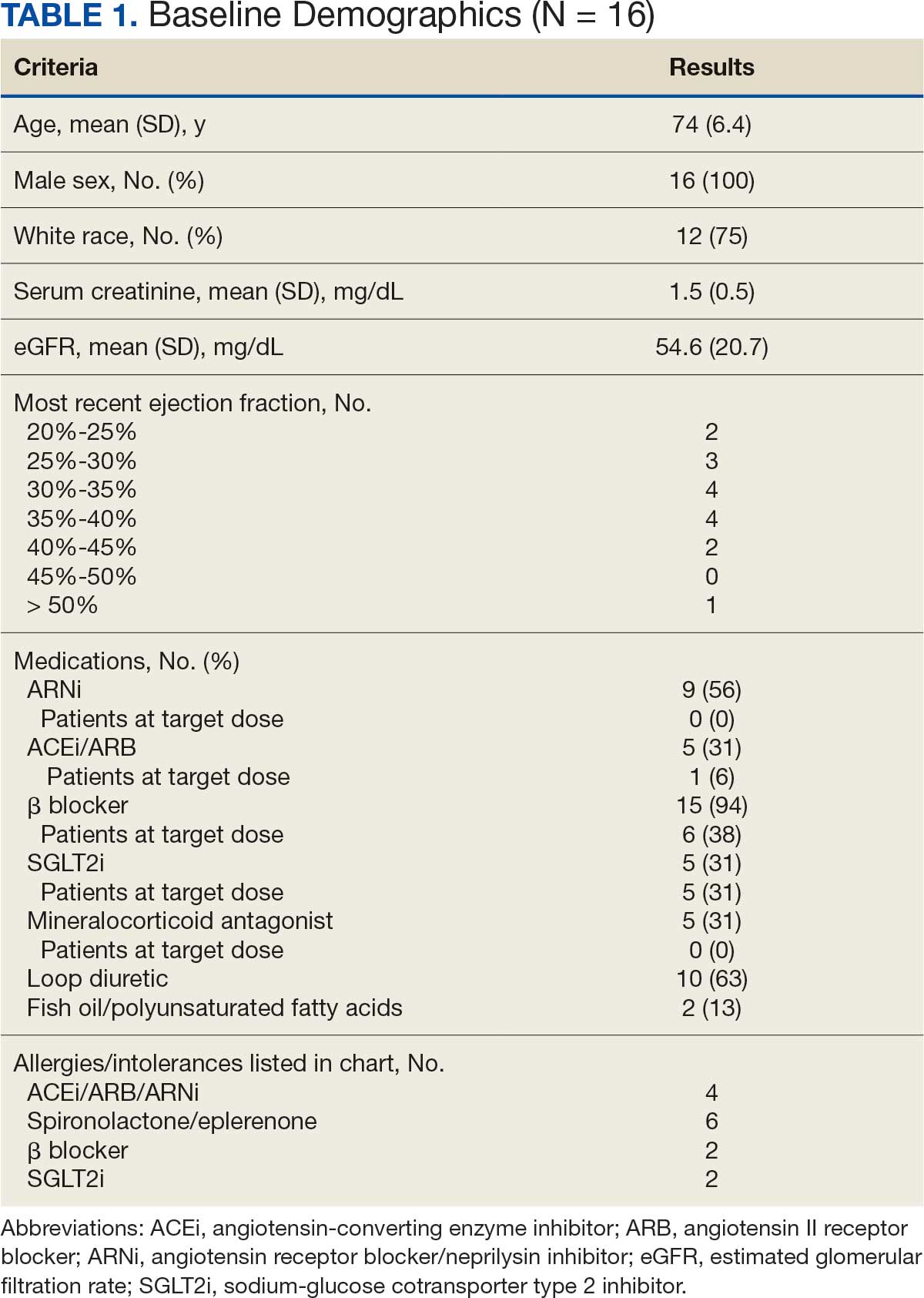

There were 39 WPBVAMC patients with a HeartLogic-capable device. Twenty-one alert encounters were analyzed in 16 patients (41%) over 31 weeks of data collection. The 16 patients at baseline had a mean age of 74 years, all were male, and 12 (75%) were White. Eight patients (50%) had a recent ejection fraction (EF) between 30% and 40%. Three patients had an EF ≥ 40%. At the time of alert, 15 patients used BB (94%), 10 used loop diuretics (63%), and 9 used ARNi (56%) (Table 1).

There were 23 medication changes made during initial contact. The most common change was starting an SGLT2i (30%; n = 7), followed by starting an MRA (22%; n = 5), and increasing the ARNi dose (22%; n = 5). At the initial contact, ≥ 1 medication optimization occurred in 95% (n = 20) of encounters. The CPP contacted patients a mean of 4.8 days after the initial alert.

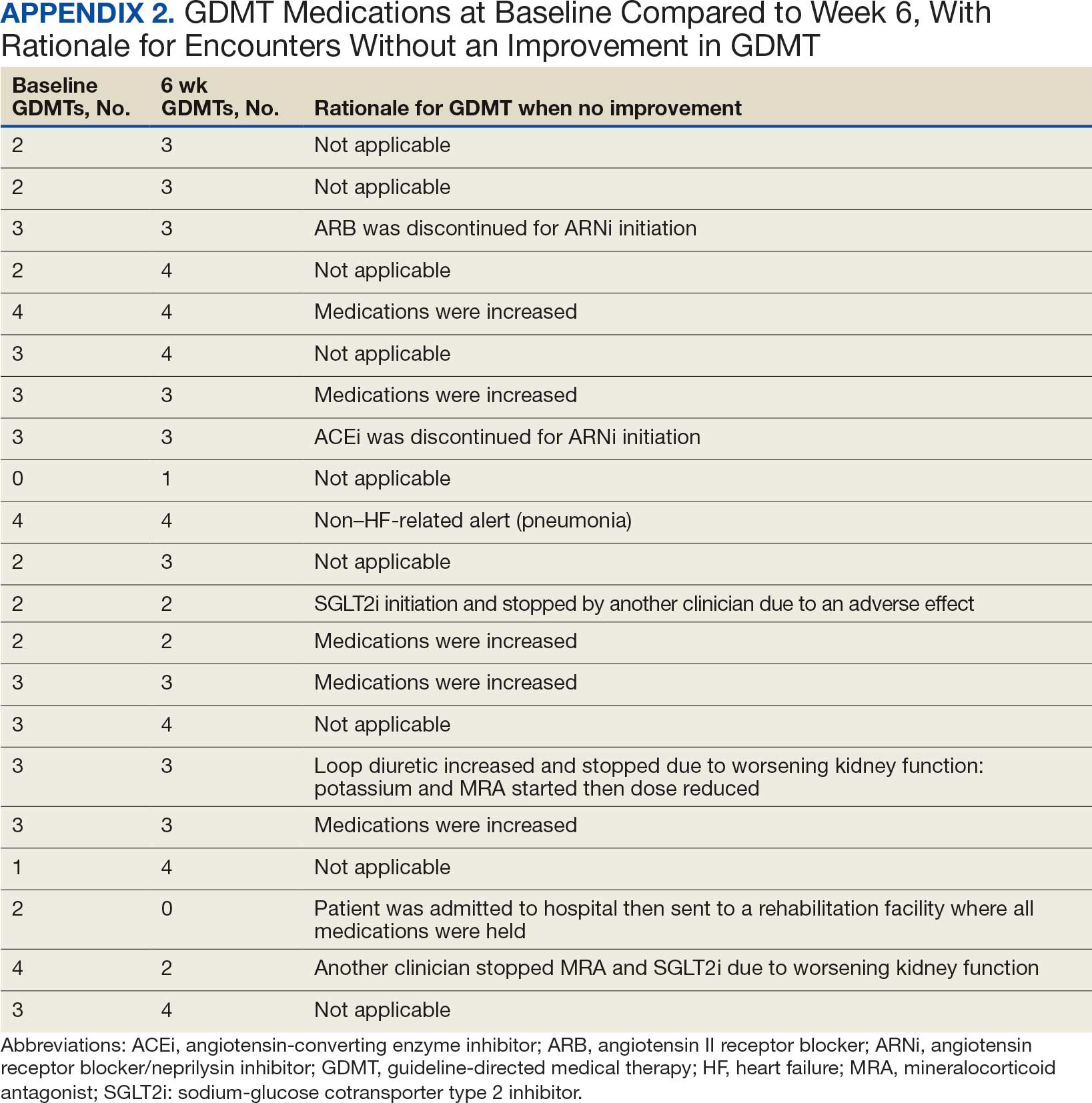

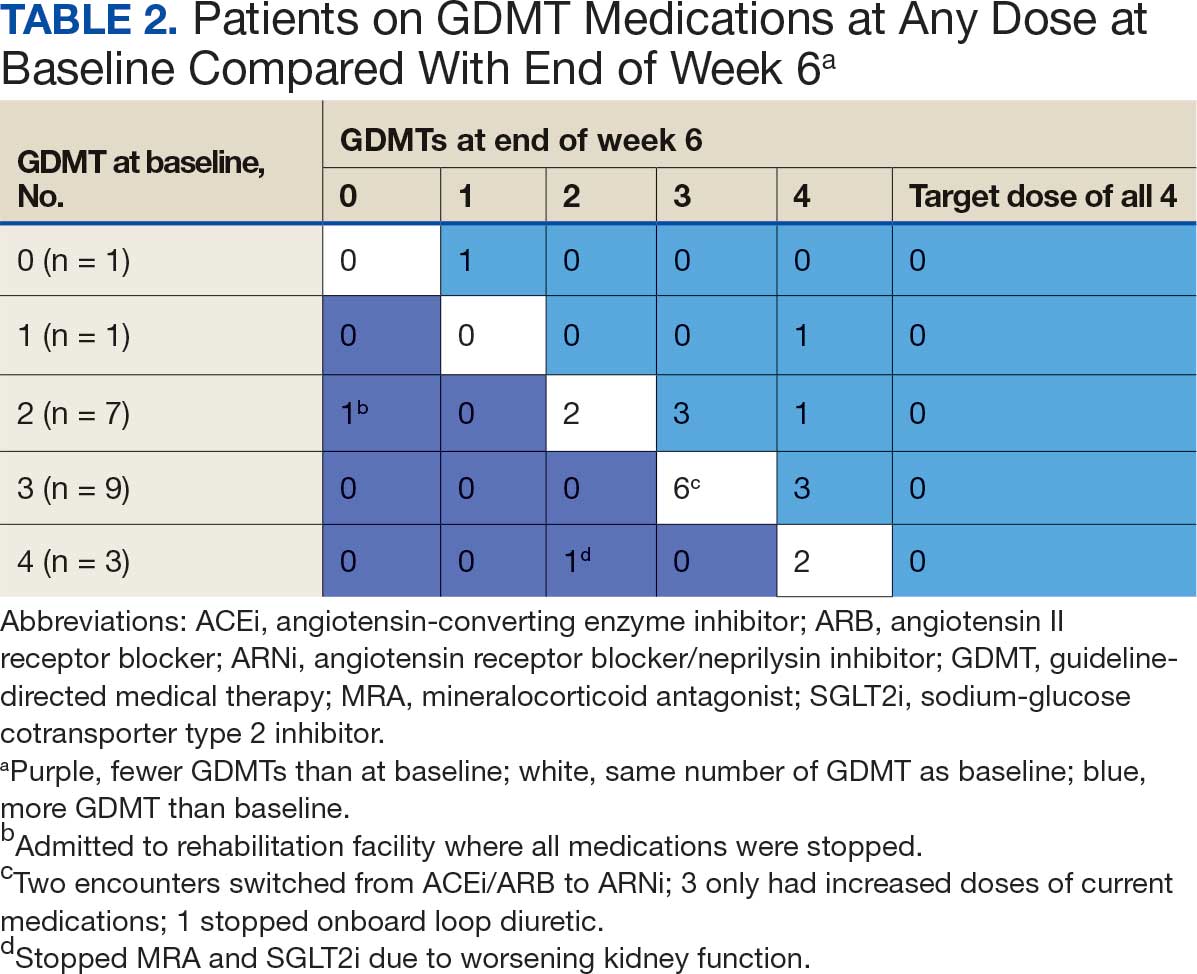

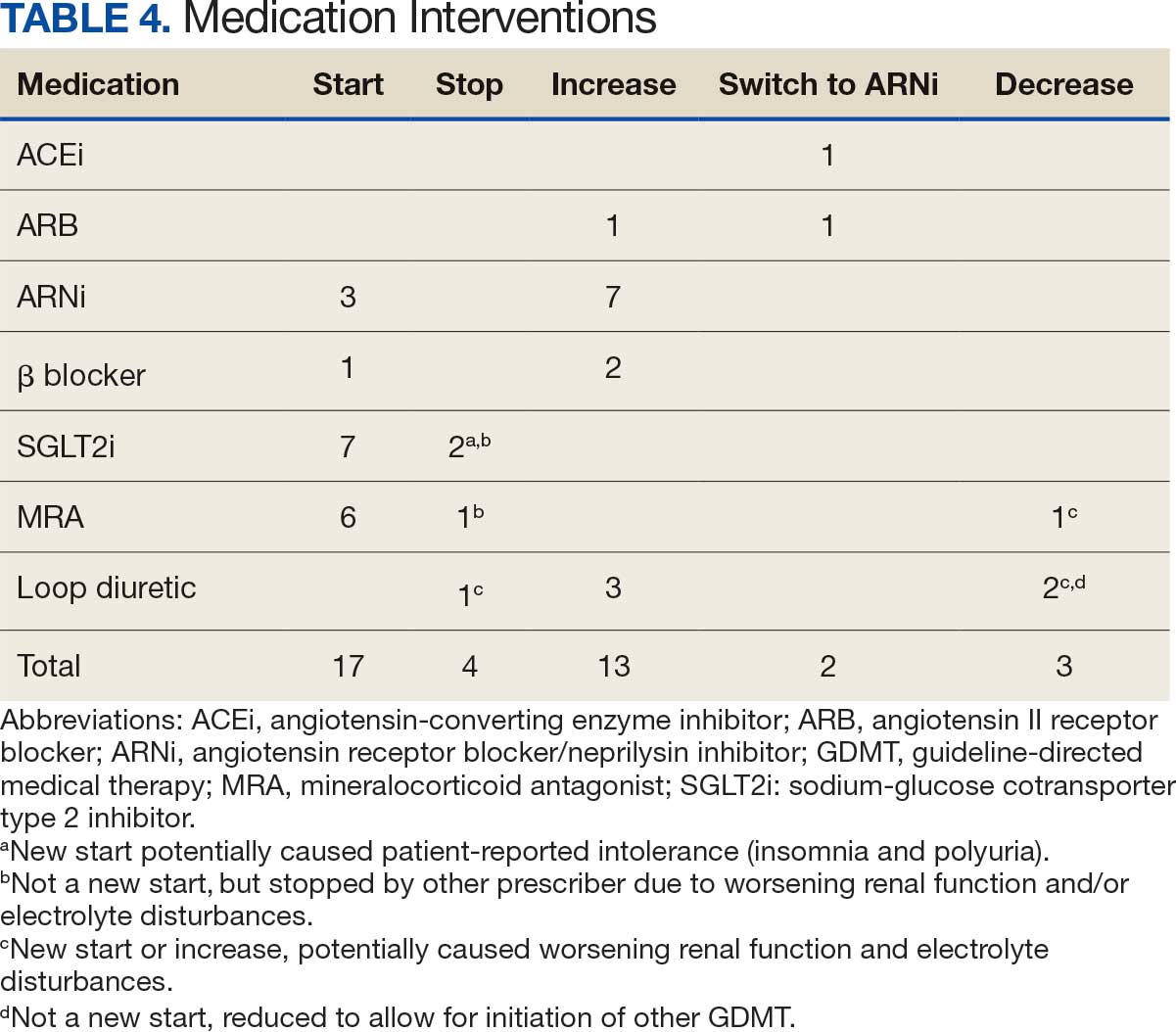

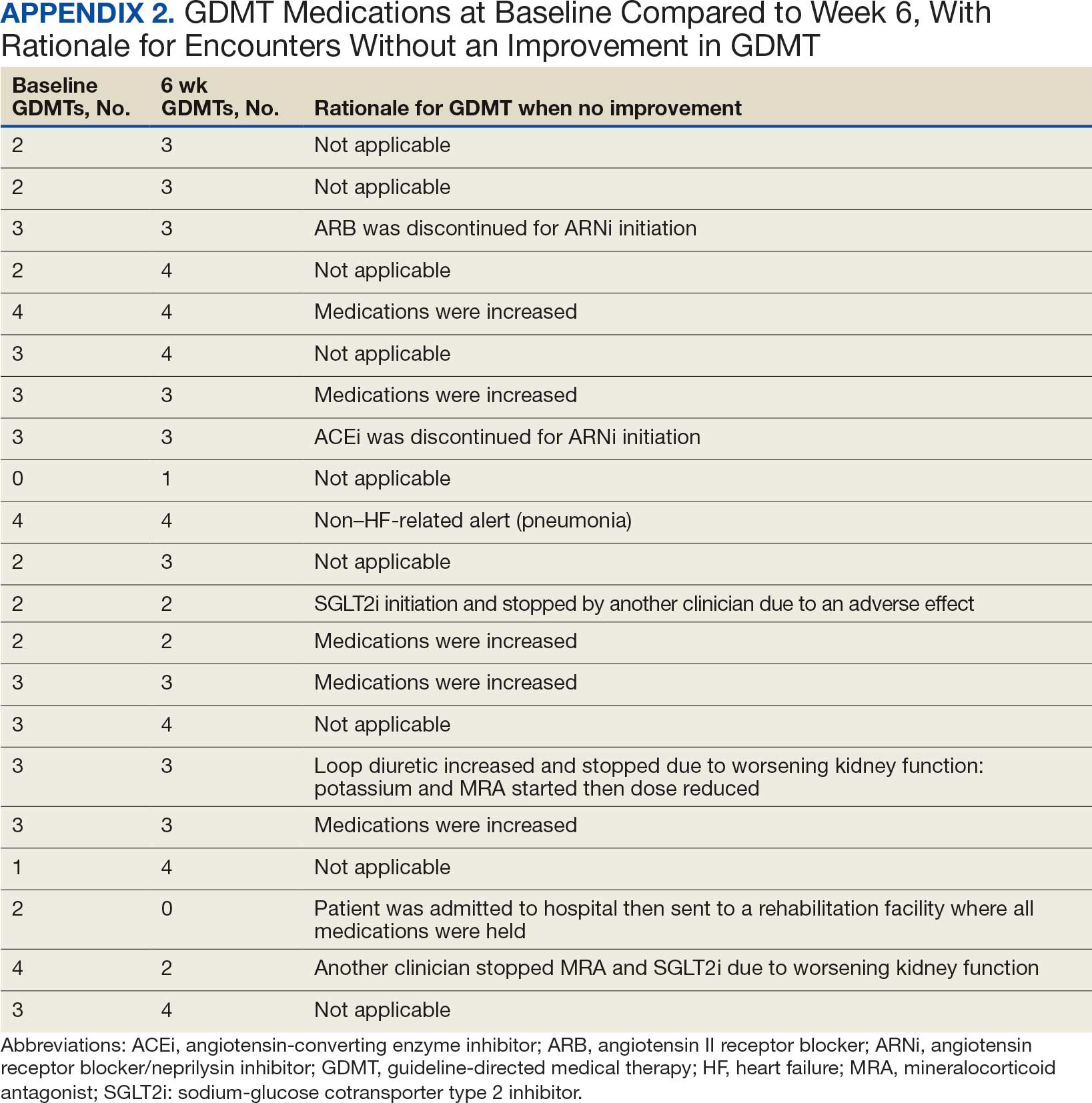

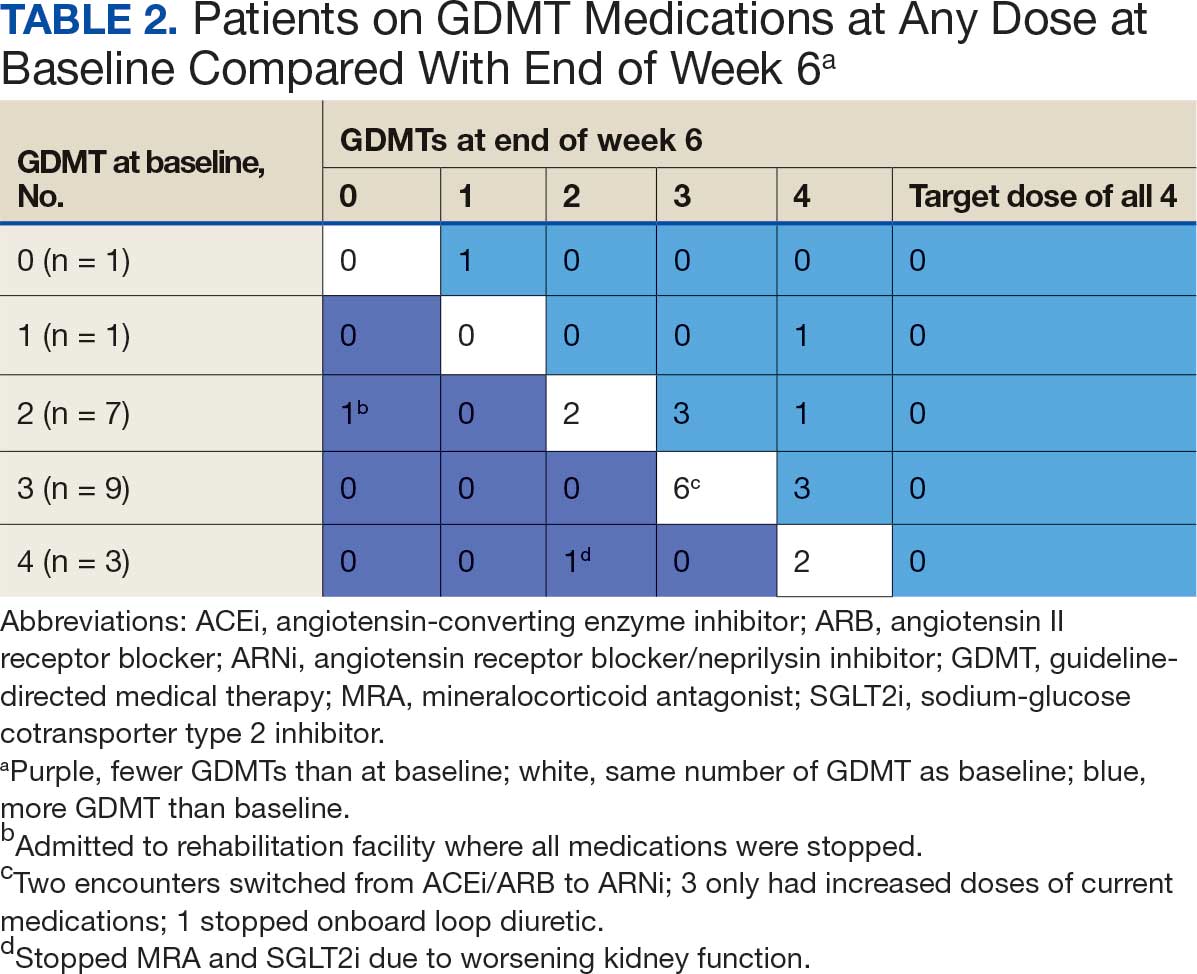

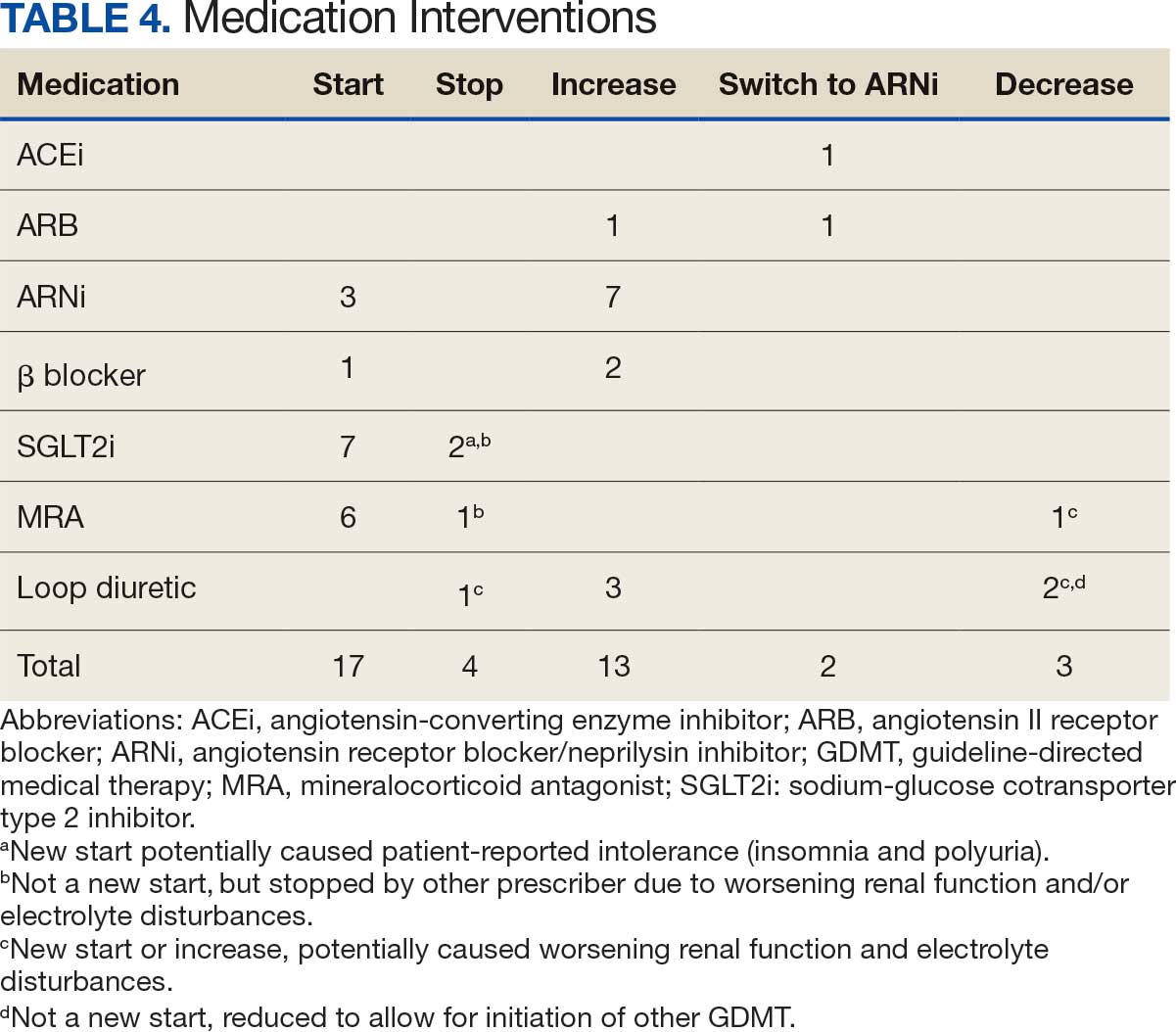

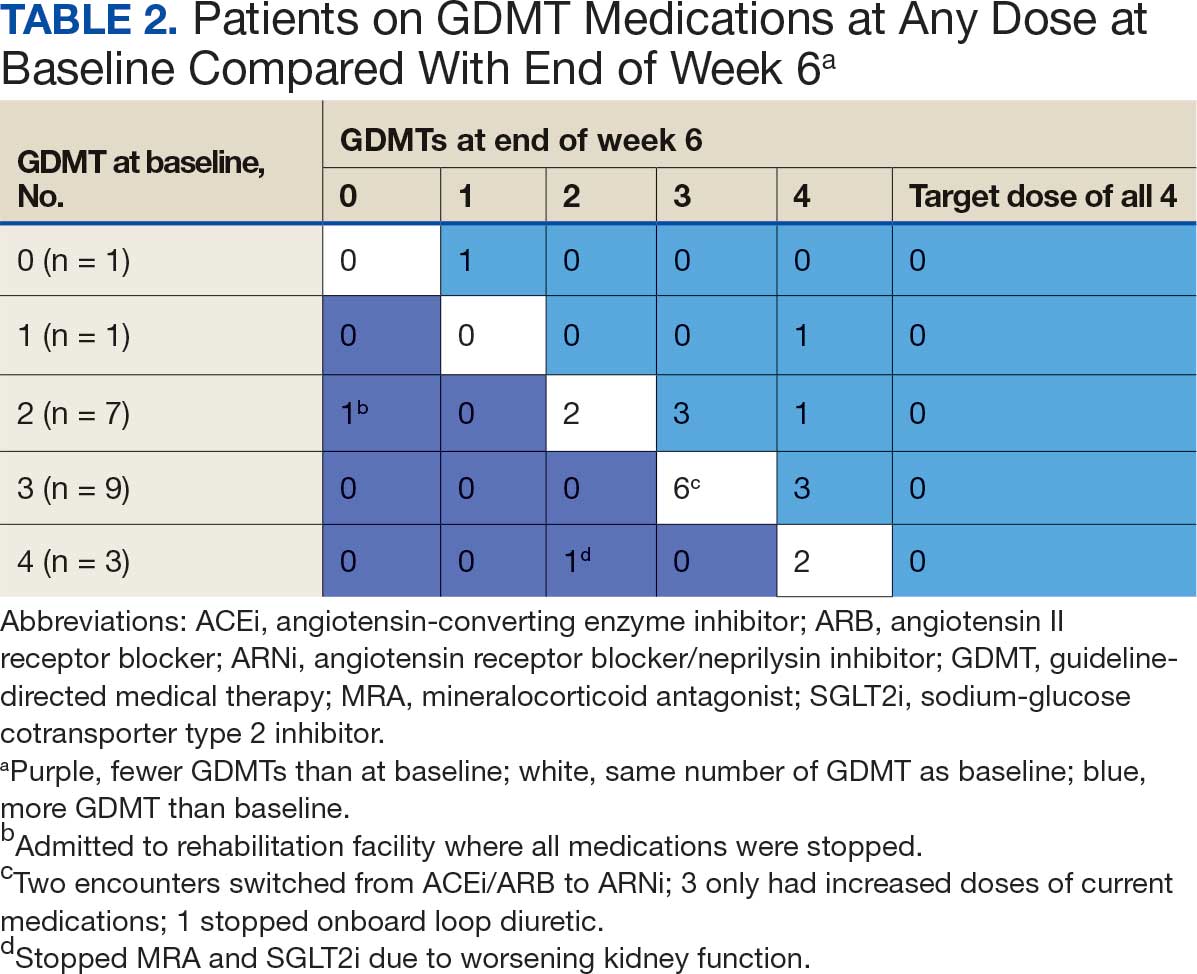

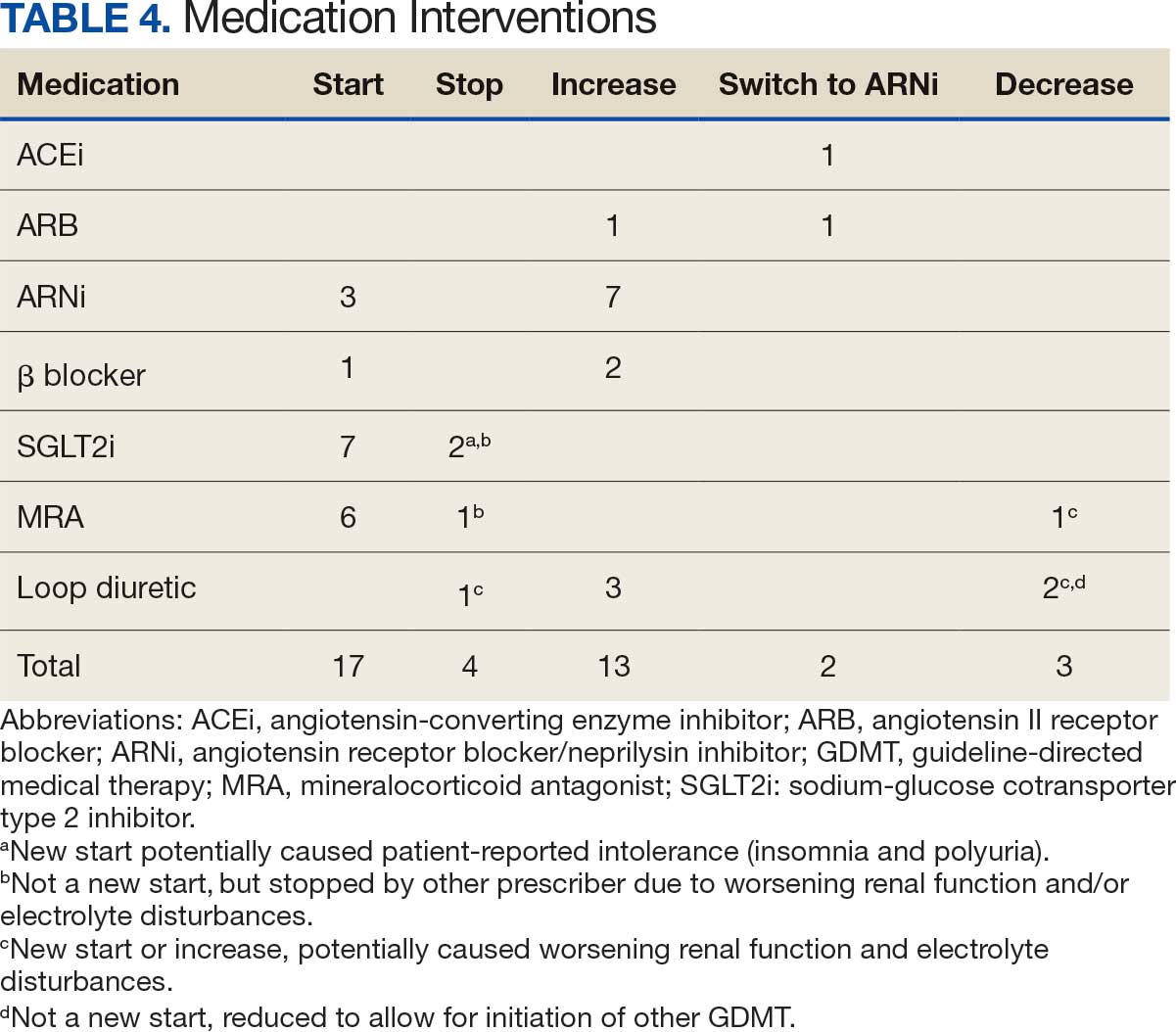

Patients were taking a mean of 2.6 primary GDMT medications at baseline and 3.0 at 42 days. CPP encounters led to a mean of 1.8 medication changes over the 6-week period (range, 0-5). Seventeen medications were started, 13 medications were increased, 3 medications were decreased, and 4 medications were stopped (Table 2). One ACEi and 1 ARB were switched as a therapy escalation to an ARNi. One patient was on 1 of 4 primary GDMTs at baseline, which increased to 4 GDMT agents at 42 days.

SGLT2 inhibitors were added most often at initial contact (54%) and throughout the 42-day period (41%). The most common successfully tolerated optimizations were RASi, followed by MRA, SGLT2 inhibitors, BB, and loop diuretics with 11, 6, 5, 3, and 2 patients, respectively. Interventions were tolerated by 90% of patients, and no HF hospitalization occurred during follow-up. All possible rationales for patients with the same or reduced number of GDMT at 42 days compared with baseline are shown in Appendix 2.

Device Metrics

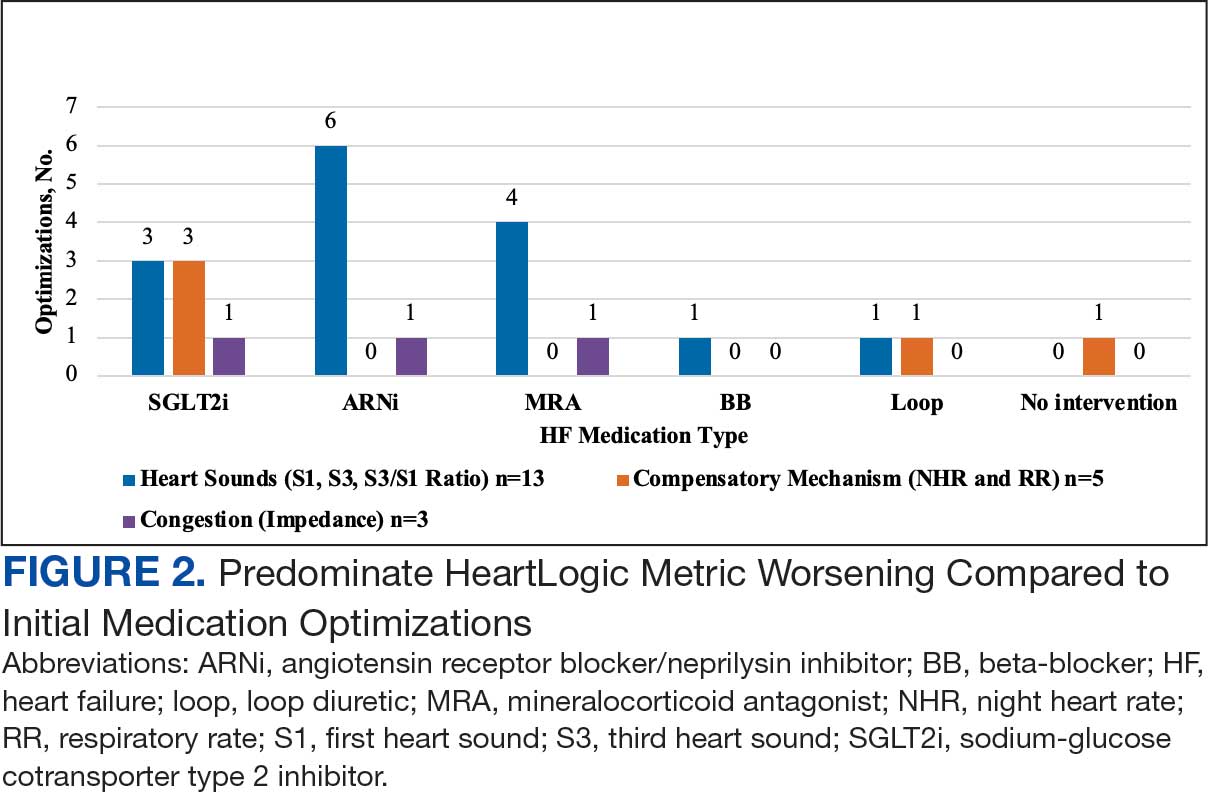

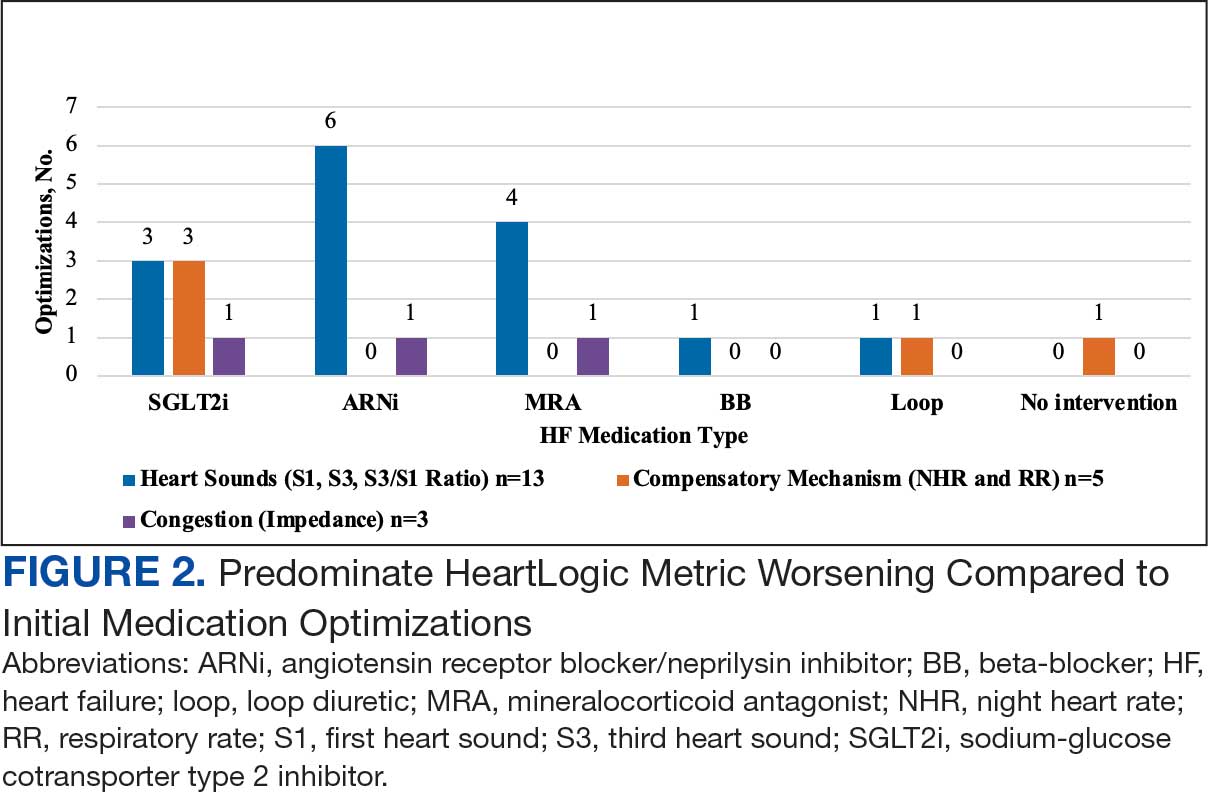

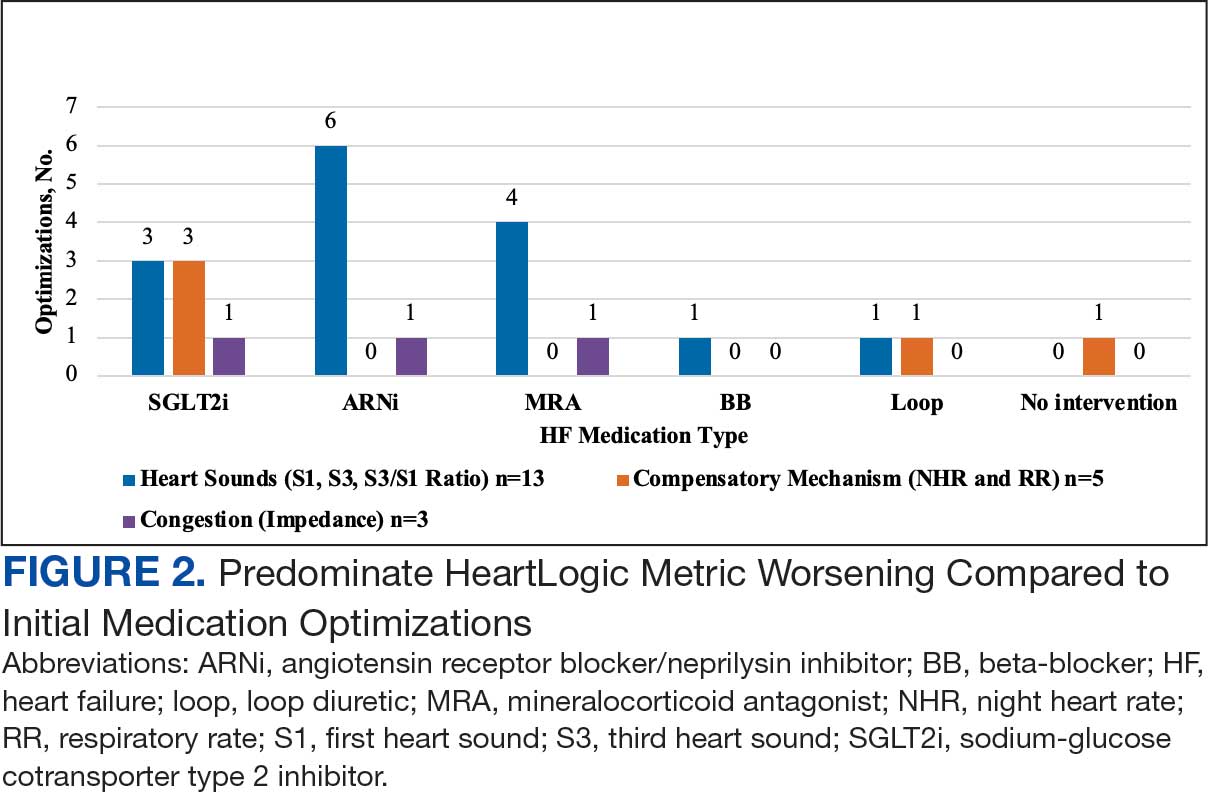

During initial contact, the most common HeartLogic metric category that was predominantly worsening were heart sounds (S1, S3, and S3/S1 ratio), followed by compensatory mechanism sensors (NHR and RR) and congestion (impedance) at rates of 61.9%, 23.8%, and 14.3%, respectively (Figure 2).

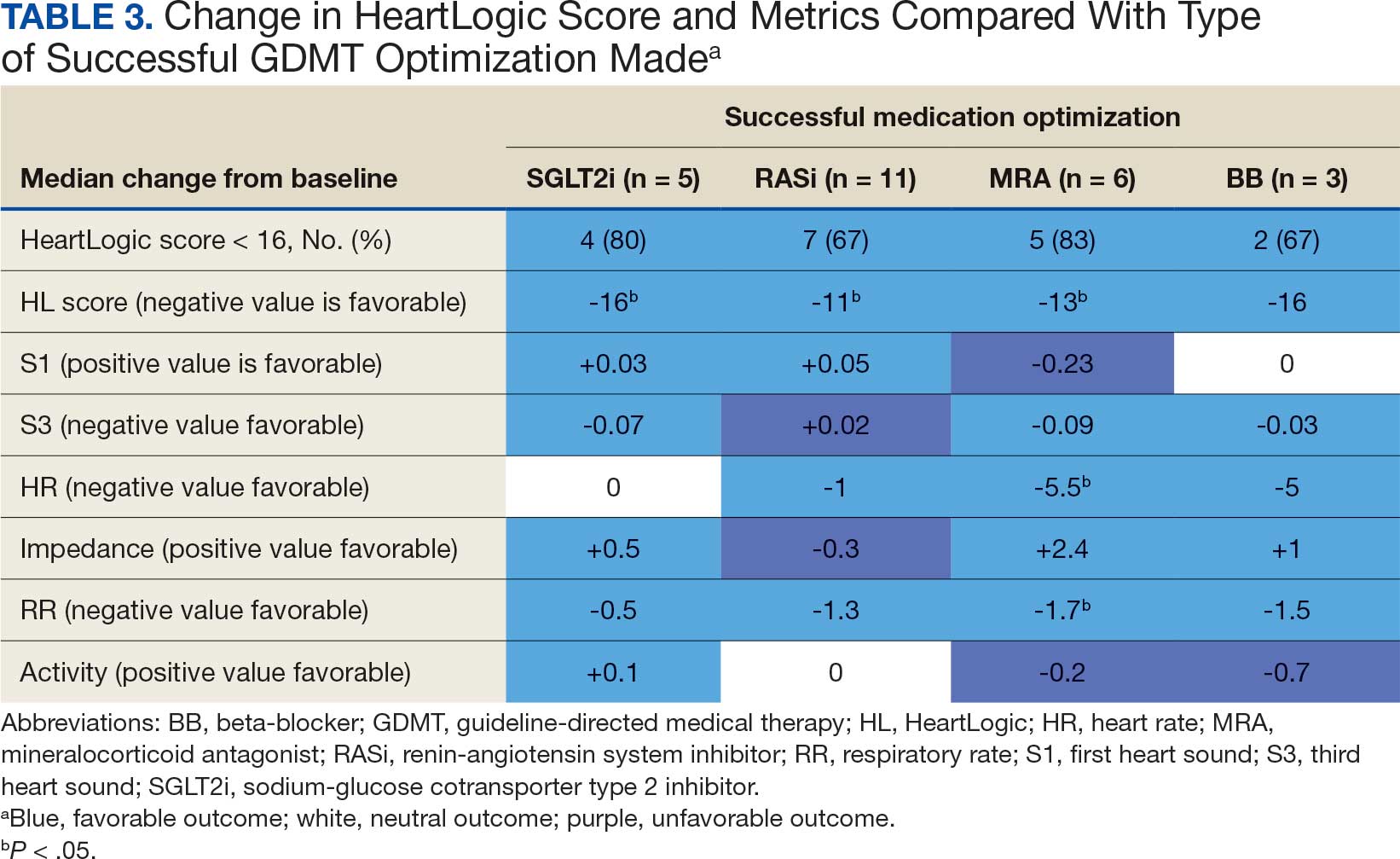

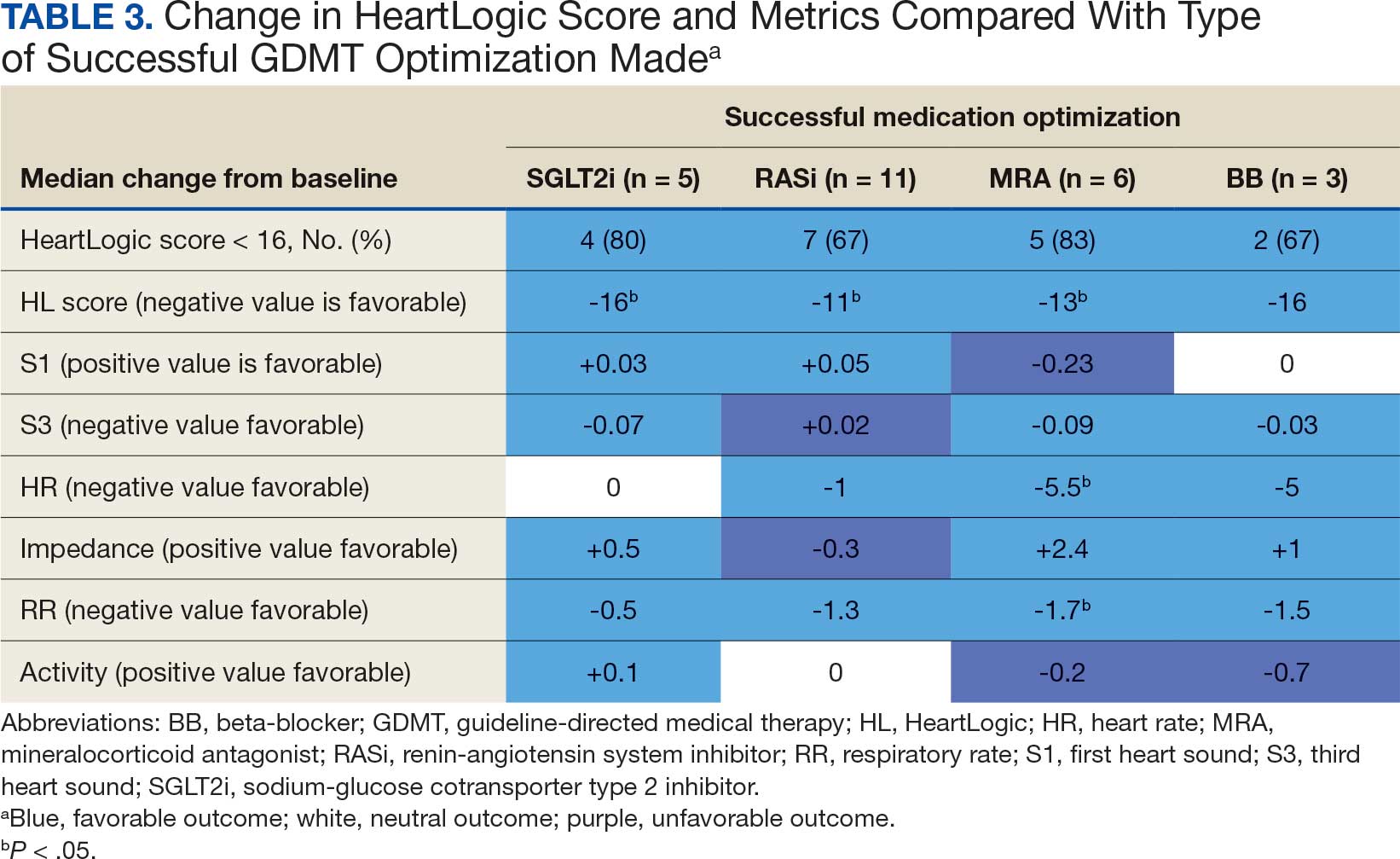

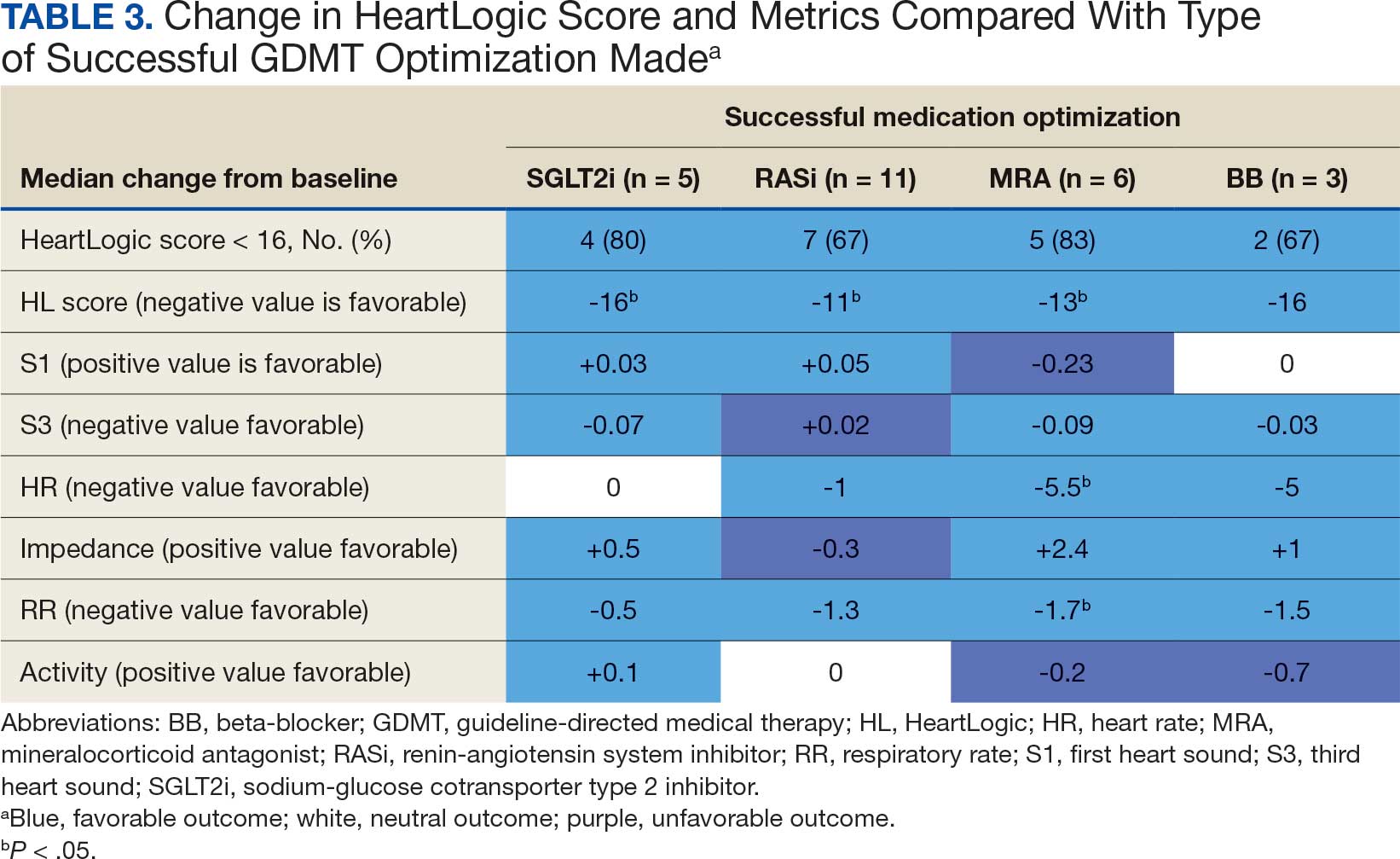

The median HeartLogic index score was 18 at baseline and 5 at the end of the follow-up period (P < .001). The changes in score and metrics were compared with the type of successfully tolerated GDMT optimization made (Table 3). The GDMT optimization analysis included SGLT2i, RASi, MRA, BB, and loop diuretics. All interventions reduced the overall HeartLogic index score, ranging from a 9.5-point reduction (loop diuretics) to a 16-point reduction (SGLT2i and BB). Optimization of SGLT2i, RASi, and loop diuretics had a positive impact on S1 score. For S3 score, SGLT2i, MRA, and BB had a positive impact. All medications, except for SGLT2i therapy, reduced the NHR score. Optimization of MRA, SGLT2i, and BB had positive impacts on the impedance score. All medications reduced RR from baseline. Only SGLT2i and loop diuretics had positive impacts on the activity score.

Clinical Outcomes and Adverse Effects

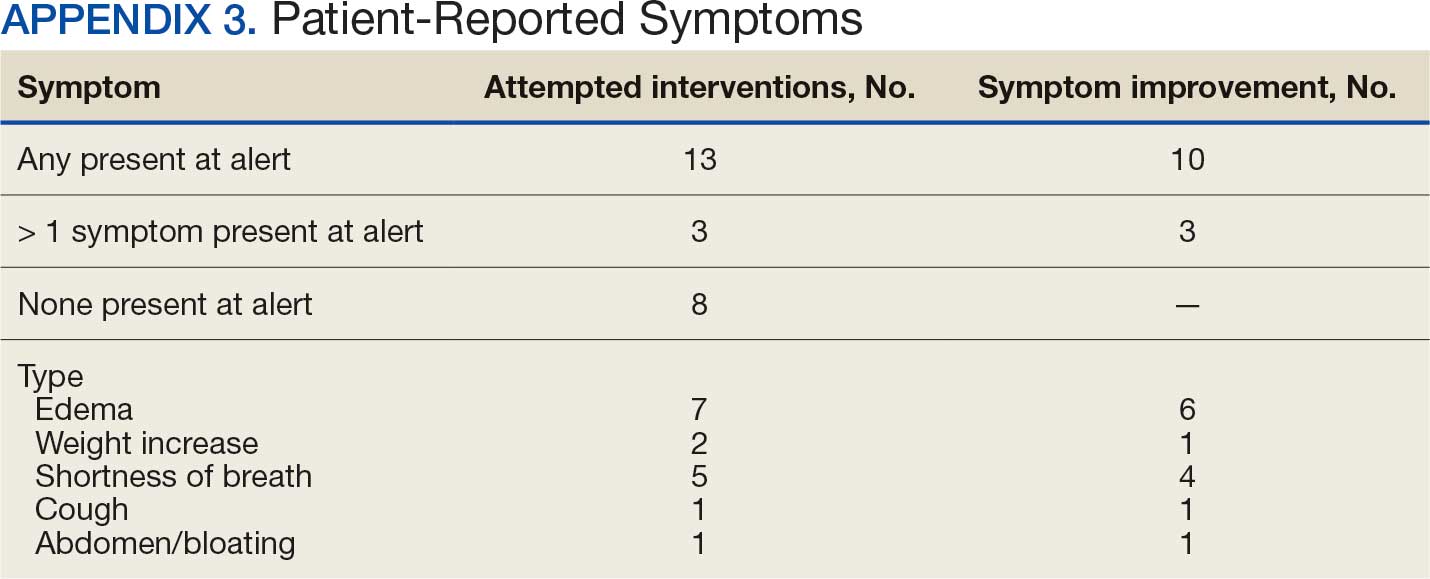

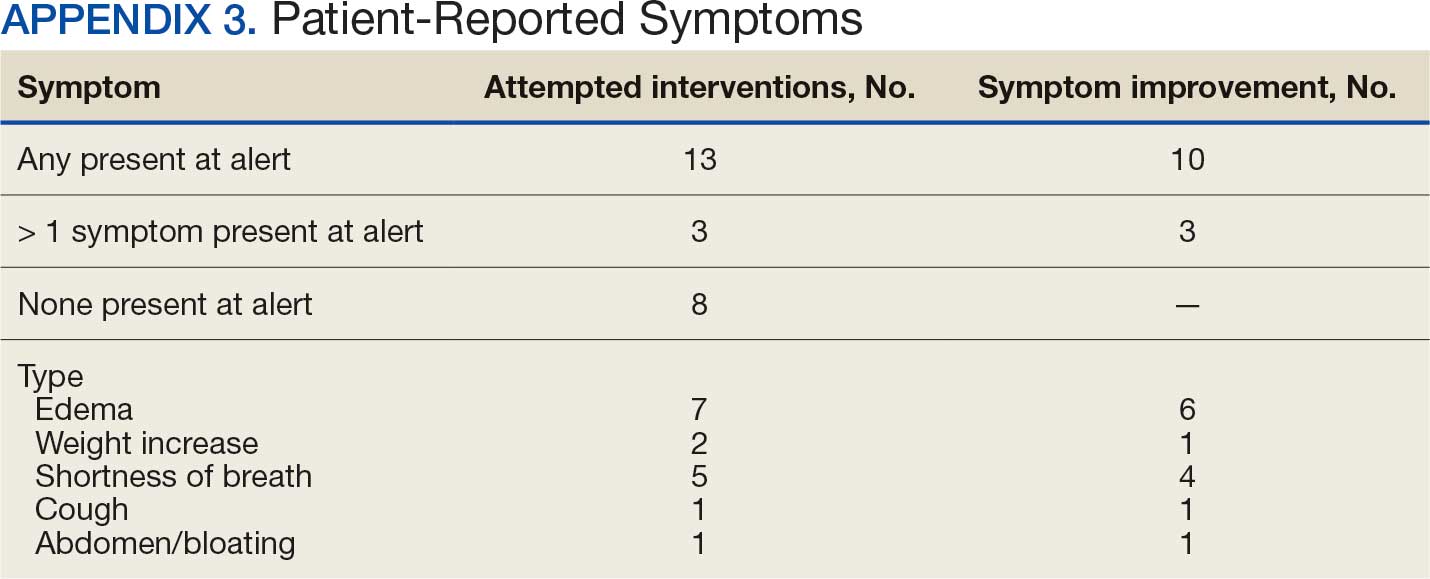

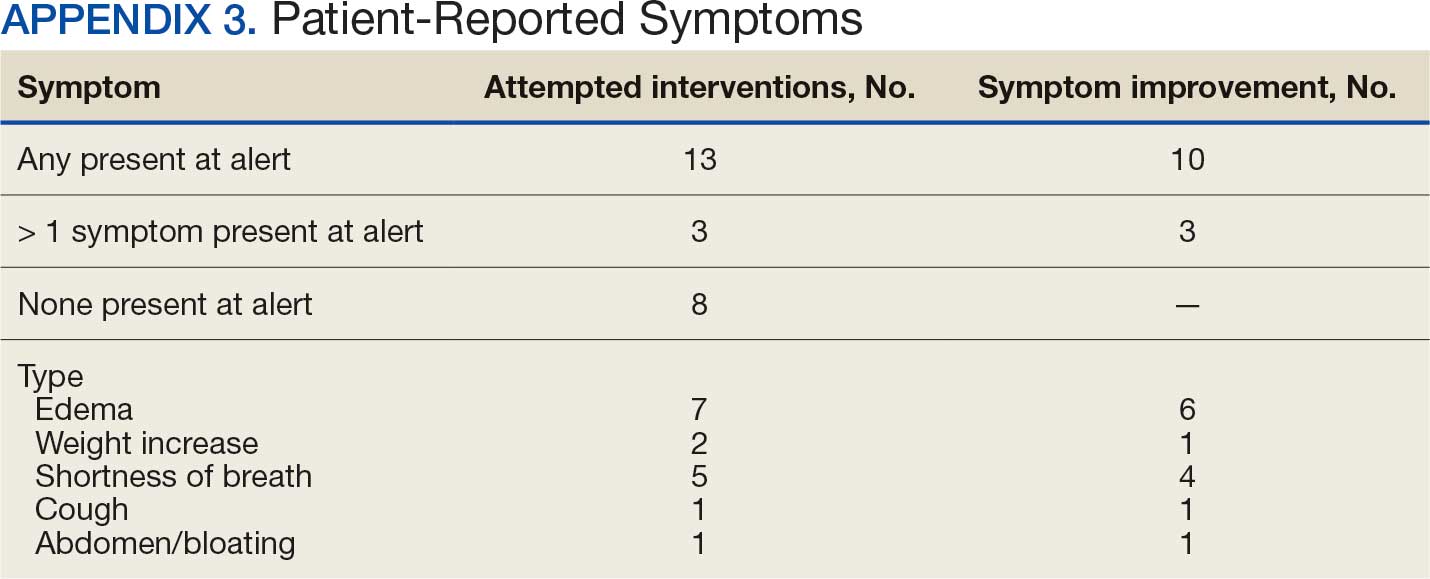

Within 42 days of contact, 17 encounters (81%) had ≥ 1 follow-up appointment with a CPP and all 21 patients had ≥ 1 follow-up health care team member. One patient had a HF-related hospitalization within 42 days of contact; however, that individual refused the recommended medication intervention. There were 13 encounters (62%) with reported symptoms at the time of the initial alert and 10 (77%) had subjective symptom improvement at 42 days (Appendix 3).

Of 30 medication optimizations, 27 primary GDMT medications were tolerated. Two medication intolerances led to discontinuation (1 SGLT2i and 1 loop diuretic) and 1 patient never started the SGLT2i (Table 4). There was only 1 known patient who did not follow the directions to adjust their medications. That individual was included because the patient agreed to the change during the CPP visit but later reported that he had never started the SGLT2i.

Discussion

The HeartLogic tool created a bridge for patients with HF to work with CPPs as soon as possible to optimize medication therapy to reduce HF events. This study highlights an additional area of expertise and service that CPPs may offer to their specialty HF clinic team. Over 31 weeks, 21 encounters and 30 medication optimizations were completed. These interventions led to significant reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care, most of which were well tolerated.

Additional hemodynamic monitoring devices are available. Similar to HeartLogic, OptiVol is a tool embedded in select Medtronic implantable devices that monitors fluid status. 14 CardioMEMS is an implantable pulmonary artery pressure sensor used as a presymptomatic data point to alert clinicians when HF is worsening. In the CHAMPION trial, the use of CardioMEMS showed a 28% reduction in HF-related hospitalization at 6 months.15 Conversely, in the GUIDE-HF trial, monitoring with CardioMEMS did not significantly reduce the composite endpoint of mortality and total HF events.16 Therefore, remote hemodynamic monitoring has variable results and the use of these tools remains uncertain per the clinical guidelines.2

The MANAGE-HF study that contributed to the validation of the HeartLogic tool may provide a comparison with this smaller single-center project. The time to follow-up within 7 days of alert was noted in only 54% of the patients in MANAGE-HF.12 In this study, 86% of patients received follow-up within 7 days, with a mean of 4.8 days. The quick turnaround from the time of alert to intervention portrays pharmacists as readily available HCPs.

In MANAGE-HF, 89% of medication augmentation involved loop diuretics or thiazides; in our project, loop diuretics were the least frequently changed medication. Most optimizations in this project included ARNi, SGLT2i, BB, and MRA, which have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.2 Our project included use of SGLT2i therapy to affect HeartLogic metrics, which has not been evaluated previously. SGLT2i were the most commonly initiated medication after an alert. Of the 5 tolerated SGLT2i optimization encounters, 4 were out of alert at 42 days.

SGLT2i resulted in a significant decrease in HeartLogic index score from baseline and were the only class of medication that did not produce a negative change in any metric. In this study, CPPs utilizing and acting on HeartLogic alerts led to 1 (4.8%) hospitalization with HF as the primary reason for admission and no hospitalizations as a secondary cause in 42 days, compared to 37% and 7.9% in the MANAGE-HF in 1 year, respectively. An additional screening 1 year after the initial alert found that 2 (12.5%) of 12 patients had been admitted with 1 HF hospitalization each.

A strength of this study was the ability to use HeartLogic to identify high-risk patients, provide a source of patient contact and monitoring, interpret 5 cardiac sensors, and optimize all HF GDMT, not just volume management. By focusing efforts on making patient contact and pharmacotherapy interventions with morbidity and mortality benefit, remote hemodynamic monitoring may show a clear clinical benefit and become a vital part of HF care.

Limitations

Checking for adherence and tolerance to medications were mainly patient reported if there was a CPP follow-up within 42 days, or potentially through refill history when unclear. However, this limitation is reflective of current practice where patients may have multiple clinicians working to optimize HF care and where there is reliance on patients in order to guide continued therapy. Although unable to explicitly show a reduction in HF events given lack of comparator group, the interventions made are associated with improved outcomes and thus would be expected to improve patient outcomes. Changes in vital signs were not tracked as part of this project, however the main rationale for changes made were to optimize GDMT therapy, not specifically to impact vital sign measures.

HeartLogic alerts prompted identification of high-risk patients with HF, pharmacist evaluation and outreach, patient-focused pharmacotherapy care, and beneficial patient outcomes. With only 2 cardiology CPPs checking alerts once weekly, future studies may be needed with larger samples to create algorithms and protocols to increase the clinical utility of this tool on a greater scale.

Conclusions

Cardiology CPP-led HF interventions triggered by HeartLogic alerts lead to effective patient identification, increased access to care, reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care. This project demonstrates the practical utility of the HeartLogic suite in conjunction with CPP care to prioritize treatment for highrisk patients with HF in an efficient manner. The data highlight the potential value of the HeartLogic tool and a CPP in HF care to facilitate initiation and optimization of GDMT to ultimately improve the morbidity and mortality in patients with HF.

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93-e621. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e895-e1032. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

- Boehmer JP, Hariharan R, Devecchi FG, et al. A multisensor algorithm predicts heart failure events in patients with implanted devices: results from the MultiSENSE study. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017;5:216-225. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.011

- Cao M, Gardner RS, Hariharan R, et al. Ambulatory monitoring of heart sounds via an implanted device is superior to auscultation for prediction of heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2020;26:151-159. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.10.006

- Calò L, Capucci A, Santini L, et al. ICD-measured heart sounds and their correlation with echocardiographic indexes of systolic and diastolic function. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;58:95-101. doi:10.1007/s10840-019-00668

- Del Buono MG, Arena R, Borlaug BA, et al. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure: JACC state-of-the- art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2209-2225. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.072

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Rials S, Aktas M, An Q, et al. Continuous respiratory rate is superior to routine outpatient dyspnea assessment for predicting heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2018;24:S45.

- Fonarow GC, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(suppl 7):S21-S30. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.07.130

- Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:823-830. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.079

- De Ruvo E, Capucci A, Ammirati F, et al. Preliminary experience of remote management of heart failure patients with a multisensor ICD alert [abstract P1536]. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(suppl S1):370.

- Hernandez AF, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Multiple cardiac sensors for management of heart failure (MANAGE- HF) - phase I evaluation of the integration and safety of the HeartLogic multisensor algorithm in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2022;28:1245-1254. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.03.349

- Santini L, D’Onofrio A, Dello Russo A, et al. Prospective evaluation of the multisensor HeartLogic algorithm for heart failure monitoring. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:691-697. doi:10.1002/clc.23366

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Adamson PB, Abraham WT, Stevenson LW, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided heart failure management reduces 30-day readmissions. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002600. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002600

- Lindenfeld J, Zile MR, Desai AS, et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398:991-1001. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01754-2

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent disease in the United States affecting > 6.5 million adults and contributing to significant morbidity and mortality.1 The disease course associated with HF includes potential symptom improvement with intermittent periods of decompensation and possible clinical deterioration. Multiple therapies have been developed to improve outcomes in people with HF—to palliate HF symptoms, prevent hospitalizations, and reduce mortality.2 However, the risks of decompensation and hospitalization remain. HF decompensation development may precede clear actionable symptoms such as worsening dyspnea, noticeable edema, or weight gain. Tools to identify patient deterioration and trigger interventions to prevent HF admissions are clinically attractive compared with reliance on subjective factors alone.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices made by Boston Scientific include the HeartLogic monitoring feature. Five main sensors produce an index risk score; an index score > 16 warns clinicians that the patient is at an increased risk for a HF event.3 The 5 sensors are thoracic impedance, first (S1) and third heart sounds (S3), night heart rate (NHR), respiratory rate (RR), and activity. Each sensor can draw attention to the primary driver of the alert and guide health care practitioners (HCPs) to the appropriate interventions.3 A HeartLogic alert example is shown in Figure 1.

The S3 occurs during the early diastolic phase when blood moves into the ventricles. As HF worsens, with a combination of elevated filling pressures and reduced cardiac muscle compliance, S3 can become more pronounced.4 The S1 is correlated with the contractility of the left ventricle and will be reduced in patients at risk for HF events.5 Physical activity is a long-term prognostic marker in patients with HF; reduced activity is associated with mortality and increased risk of an HF event.6 Thoracic impedance is a sensor used to identify pulmonary congestion, pocket infections, pleural/pericardial effusion, and respiratory infections. The accumulation of intrathoracic fluid during pulmonary congestion increases conductance, causing a decrease in impedance.7 RR will increase as patients experience dyspnea with a more rapid, shallow breath and may trigger alerts closer to the actual HF event than other sensors. Nearly 90% of patients hospitalized for HF experience shortness of breath.8,9 NHR is used as a surrogate for resting heart rate (HR). A high resting HR is correlated with the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, harmful effects on left ventricular function, and increased risk of myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias.10

One of the challenges with preventing hospitalizations may be the lack of patient reported symptoms leading up to the event. The purpose of the sensors and HeartLogic index is to identify patients a median of 34 days before an HF event (HF admission or unscheduled intervention with intravenous treatment) with a sensitivity rate of 70%.3 According to real-word experience data, alerts have been found to precede HF symptoms by a median of 12 days and HF events such as hospitalizations by a median of 38 days, with an overall 67% reduction in HF hospitalizations when integrated into clinical care.11,12

MANAGE-HF evaluated 191 patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (< 35%), New York Heart Association class II-III symptoms, and who had an implanted CRT and/or ICD to develop an alert management guide to optimize medical treatment.12 It aimed to adjust patient regimen within 6 days of an elevated Heart- Logic index by either initiation, escalation, or maintenance of HF treatment depending on the index trend after the initial alert. This trial found that by focusing on such optimization, HF treatment was augmented during 74% of the 585 alert cases and during 54% of 3290 weekly alerts.

Initiation and uptitration of the 4 primary components of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) are recommended by the 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with HFrEF.2 The 4 pillars of GDMT consist of -blockers (BB), sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi) including angiotensin II receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) (Appendix 1). Obtaining and titrating to target doses wherever possible is recommended, as those were the doses that established safety and efficacy in patients with HFrEF in clinical trials.2 Pharmacists are adequately equipped to optimize HF GDMT and appropriately monitor drug response.

Through the use of HeartLogic in clinical practice, patients with HF have been shown to have improved clinical outcomes and are more likely to receive effective care; 80% of alerts were shown to provide new information to clinicians.13 This project sought to quantify the total number and types of pharmacist interventions driven by integration of HeartLogic index monitoring into practice.

Methods

The West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC) Research Program Office approved this project and determined it was exempt from institutional review board oversight. Patients were screened retrospectively and prospectively from May 26, 2022, through December 31, 2022, by a cardiology clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) and a cardiology pharmacy resident using the local monitoring suite for the HeartLogic-compatible device, LATITUDE NXT. Read-only access to the local monitoring suit was granted by the National Cardiac Device Surveillance Program. Training for HeartLogic was completed through continuing education courses provided by Boston Scientific. Additional information was provided by Boston Scientific representative presentations and collaboration with WPBVAMC pacemaker clinic HCPs.

Individuals included were patients with HeartLogic-capable ICDs. A HeartLogic alert had to be present at initial patient contact. Patients were also contacted as part of routine clinical practice, but no formal number or frequency of calls to patients was required. The initial contact must be with a pharmacist for the patient to be included, but subsequent contact by other HCPs was included. Patients in the cardiology clinic are required to meet with a cardiologist at least annually; however, interim visits can be completed by advanced practice registered nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, or CPPs.

Patients in alert status were contacted by telephone and appropriate modifications of HF therapy were made by the CPP based on score metrics, medical record review, and patient interview. Information surrounding the initial alert, baseline patient data, medication and monitoring interventions made, and clinical outcomes such as hospitalization, symptom improvement, follow-up, and mortality were collected. Information for each encounter was collected until 42 days from the initial date of pharmacist contact.

Clinically successful tolerability of intervention implementation was defined as tolerability, adherence, and lack of adverse effects (AEs) per patient report at follow-up or within 42 days from initial alert (Appendix 2). A decrease in dose was not counted as intolerance. A single patient may have been counted as multiple encounters if the original intervention resulted in treatment intolerance and the patient remained in alert or if an additional alert occurred after 42 days of the initial alert. There were no specific time criteria for follow-up, which occurred at the CPP’s discretion.

There was no mandated algorithm used to alter medications based on the Heart- Logic score, nor were there required minimum or maximum numbers of interventions after an alert. Patient contact by telephone initiated an encounter. The types of interventions included medication increases, decreases, initiation, discontinuation, or no medication change. Each medication change and rationale, if applicable, was recorded for the encounter ≤ 42 days after the initial contact date. If a medication with required monitoring parameters was augmented, the pharmacist was responsible for ordering laboratory testing and follow-up. Most interventions were completed by telephone; however, some patients had in-person visits in the HF CPP clinic.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of pharmacist interventions made to optimize GDMT, defined as either an initiation or dose increase. Key intervention analysis included the use and dosing of the 4 primary components of HF GDMT: BB, SGLT2i, MRA, and ARNi/ARB/ACEi. In addition to the 4 primary components of GDMT, loop diuretic changes were also recorded and analyzed. Secondary endpoints were the number of HF hospitalizations ≤ 42 days after the initial alert, and the effect of medication interventions on device metrics, patient symptoms, and tolerability. Successful tolerability was defined as continued use of augmented GDMT without intolerance or discontinuation. The primary analysis was analyzed through descriptive statistics. Median changes in HeartLogic scores and metrics from baseline were analyzed using a paired, 2-sided t test with an α of .05 to detect significance.

Results

There were 39 WPBVAMC patients with a HeartLogic-capable device. Twenty-one alert encounters were analyzed in 16 patients (41%) over 31 weeks of data collection. The 16 patients at baseline had a mean age of 74 years, all were male, and 12 (75%) were White. Eight patients (50%) had a recent ejection fraction (EF) between 30% and 40%. Three patients had an EF ≥ 40%. At the time of alert, 15 patients used BB (94%), 10 used loop diuretics (63%), and 9 used ARNi (56%) (Table 1).

There were 23 medication changes made during initial contact. The most common change was starting an SGLT2i (30%; n = 7), followed by starting an MRA (22%; n = 5), and increasing the ARNi dose (22%; n = 5). At the initial contact, ≥ 1 medication optimization occurred in 95% (n = 20) of encounters. The CPP contacted patients a mean of 4.8 days after the initial alert.

Patients were taking a mean of 2.6 primary GDMT medications at baseline and 3.0 at 42 days. CPP encounters led to a mean of 1.8 medication changes over the 6-week period (range, 0-5). Seventeen medications were started, 13 medications were increased, 3 medications were decreased, and 4 medications were stopped (Table 2). One ACEi and 1 ARB were switched as a therapy escalation to an ARNi. One patient was on 1 of 4 primary GDMTs at baseline, which increased to 4 GDMT agents at 42 days.

SGLT2 inhibitors were added most often at initial contact (54%) and throughout the 42-day period (41%). The most common successfully tolerated optimizations were RASi, followed by MRA, SGLT2 inhibitors, BB, and loop diuretics with 11, 6, 5, 3, and 2 patients, respectively. Interventions were tolerated by 90% of patients, and no HF hospitalization occurred during follow-up. All possible rationales for patients with the same or reduced number of GDMT at 42 days compared with baseline are shown in Appendix 2.

Device Metrics

During initial contact, the most common HeartLogic metric category that was predominantly worsening were heart sounds (S1, S3, and S3/S1 ratio), followed by compensatory mechanism sensors (NHR and RR) and congestion (impedance) at rates of 61.9%, 23.8%, and 14.3%, respectively (Figure 2).

The median HeartLogic index score was 18 at baseline and 5 at the end of the follow-up period (P < .001). The changes in score and metrics were compared with the type of successfully tolerated GDMT optimization made (Table 3). The GDMT optimization analysis included SGLT2i, RASi, MRA, BB, and loop diuretics. All interventions reduced the overall HeartLogic index score, ranging from a 9.5-point reduction (loop diuretics) to a 16-point reduction (SGLT2i and BB). Optimization of SGLT2i, RASi, and loop diuretics had a positive impact on S1 score. For S3 score, SGLT2i, MRA, and BB had a positive impact. All medications, except for SGLT2i therapy, reduced the NHR score. Optimization of MRA, SGLT2i, and BB had positive impacts on the impedance score. All medications reduced RR from baseline. Only SGLT2i and loop diuretics had positive impacts on the activity score.

Clinical Outcomes and Adverse Effects

Within 42 days of contact, 17 encounters (81%) had ≥ 1 follow-up appointment with a CPP and all 21 patients had ≥ 1 follow-up health care team member. One patient had a HF-related hospitalization within 42 days of contact; however, that individual refused the recommended medication intervention. There were 13 encounters (62%) with reported symptoms at the time of the initial alert and 10 (77%) had subjective symptom improvement at 42 days (Appendix 3).

Of 30 medication optimizations, 27 primary GDMT medications were tolerated. Two medication intolerances led to discontinuation (1 SGLT2i and 1 loop diuretic) and 1 patient never started the SGLT2i (Table 4). There was only 1 known patient who did not follow the directions to adjust their medications. That individual was included because the patient agreed to the change during the CPP visit but later reported that he had never started the SGLT2i.

Discussion

The HeartLogic tool created a bridge for patients with HF to work with CPPs as soon as possible to optimize medication therapy to reduce HF events. This study highlights an additional area of expertise and service that CPPs may offer to their specialty HF clinic team. Over 31 weeks, 21 encounters and 30 medication optimizations were completed. These interventions led to significant reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care, most of which were well tolerated.

Additional hemodynamic monitoring devices are available. Similar to HeartLogic, OptiVol is a tool embedded in select Medtronic implantable devices that monitors fluid status. 14 CardioMEMS is an implantable pulmonary artery pressure sensor used as a presymptomatic data point to alert clinicians when HF is worsening. In the CHAMPION trial, the use of CardioMEMS showed a 28% reduction in HF-related hospitalization at 6 months.15 Conversely, in the GUIDE-HF trial, monitoring with CardioMEMS did not significantly reduce the composite endpoint of mortality and total HF events.16 Therefore, remote hemodynamic monitoring has variable results and the use of these tools remains uncertain per the clinical guidelines.2

The MANAGE-HF study that contributed to the validation of the HeartLogic tool may provide a comparison with this smaller single-center project. The time to follow-up within 7 days of alert was noted in only 54% of the patients in MANAGE-HF.12 In this study, 86% of patients received follow-up within 7 days, with a mean of 4.8 days. The quick turnaround from the time of alert to intervention portrays pharmacists as readily available HCPs.

In MANAGE-HF, 89% of medication augmentation involved loop diuretics or thiazides; in our project, loop diuretics were the least frequently changed medication. Most optimizations in this project included ARNi, SGLT2i, BB, and MRA, which have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.2 Our project included use of SGLT2i therapy to affect HeartLogic metrics, which has not been evaluated previously. SGLT2i were the most commonly initiated medication after an alert. Of the 5 tolerated SGLT2i optimization encounters, 4 were out of alert at 42 days.

SGLT2i resulted in a significant decrease in HeartLogic index score from baseline and were the only class of medication that did not produce a negative change in any metric. In this study, CPPs utilizing and acting on HeartLogic alerts led to 1 (4.8%) hospitalization with HF as the primary reason for admission and no hospitalizations as a secondary cause in 42 days, compared to 37% and 7.9% in the MANAGE-HF in 1 year, respectively. An additional screening 1 year after the initial alert found that 2 (12.5%) of 12 patients had been admitted with 1 HF hospitalization each.

A strength of this study was the ability to use HeartLogic to identify high-risk patients, provide a source of patient contact and monitoring, interpret 5 cardiac sensors, and optimize all HF GDMT, not just volume management. By focusing efforts on making patient contact and pharmacotherapy interventions with morbidity and mortality benefit, remote hemodynamic monitoring may show a clear clinical benefit and become a vital part of HF care.

Limitations

Checking for adherence and tolerance to medications were mainly patient reported if there was a CPP follow-up within 42 days, or potentially through refill history when unclear. However, this limitation is reflective of current practice where patients may have multiple clinicians working to optimize HF care and where there is reliance on patients in order to guide continued therapy. Although unable to explicitly show a reduction in HF events given lack of comparator group, the interventions made are associated with improved outcomes and thus would be expected to improve patient outcomes. Changes in vital signs were not tracked as part of this project, however the main rationale for changes made were to optimize GDMT therapy, not specifically to impact vital sign measures.

HeartLogic alerts prompted identification of high-risk patients with HF, pharmacist evaluation and outreach, patient-focused pharmacotherapy care, and beneficial patient outcomes. With only 2 cardiology CPPs checking alerts once weekly, future studies may be needed with larger samples to create algorithms and protocols to increase the clinical utility of this tool on a greater scale.

Conclusions

Cardiology CPP-led HF interventions triggered by HeartLogic alerts lead to effective patient identification, increased access to care, reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care. This project demonstrates the practical utility of the HeartLogic suite in conjunction with CPP care to prioritize treatment for highrisk patients with HF in an efficient manner. The data highlight the potential value of the HeartLogic tool and a CPP in HF care to facilitate initiation and optimization of GDMT to ultimately improve the morbidity and mortality in patients with HF.

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent disease in the United States affecting > 6.5 million adults and contributing to significant morbidity and mortality.1 The disease course associated with HF includes potential symptom improvement with intermittent periods of decompensation and possible clinical deterioration. Multiple therapies have been developed to improve outcomes in people with HF—to palliate HF symptoms, prevent hospitalizations, and reduce mortality.2 However, the risks of decompensation and hospitalization remain. HF decompensation development may precede clear actionable symptoms such as worsening dyspnea, noticeable edema, or weight gain. Tools to identify patient deterioration and trigger interventions to prevent HF admissions are clinically attractive compared with reliance on subjective factors alone.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) devices made by Boston Scientific include the HeartLogic monitoring feature. Five main sensors produce an index risk score; an index score > 16 warns clinicians that the patient is at an increased risk for a HF event.3 The 5 sensors are thoracic impedance, first (S1) and third heart sounds (S3), night heart rate (NHR), respiratory rate (RR), and activity. Each sensor can draw attention to the primary driver of the alert and guide health care practitioners (HCPs) to the appropriate interventions.3 A HeartLogic alert example is shown in Figure 1.

The S3 occurs during the early diastolic phase when blood moves into the ventricles. As HF worsens, with a combination of elevated filling pressures and reduced cardiac muscle compliance, S3 can become more pronounced.4 The S1 is correlated with the contractility of the left ventricle and will be reduced in patients at risk for HF events.5 Physical activity is a long-term prognostic marker in patients with HF; reduced activity is associated with mortality and increased risk of an HF event.6 Thoracic impedance is a sensor used to identify pulmonary congestion, pocket infections, pleural/pericardial effusion, and respiratory infections. The accumulation of intrathoracic fluid during pulmonary congestion increases conductance, causing a decrease in impedance.7 RR will increase as patients experience dyspnea with a more rapid, shallow breath and may trigger alerts closer to the actual HF event than other sensors. Nearly 90% of patients hospitalized for HF experience shortness of breath.8,9 NHR is used as a surrogate for resting heart rate (HR). A high resting HR is correlated with the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, harmful effects on left ventricular function, and increased risk of myocardial ischemia and ventricular arrhythmias.10

One of the challenges with preventing hospitalizations may be the lack of patient reported symptoms leading up to the event. The purpose of the sensors and HeartLogic index is to identify patients a median of 34 days before an HF event (HF admission or unscheduled intervention with intravenous treatment) with a sensitivity rate of 70%.3 According to real-word experience data, alerts have been found to precede HF symptoms by a median of 12 days and HF events such as hospitalizations by a median of 38 days, with an overall 67% reduction in HF hospitalizations when integrated into clinical care.11,12

MANAGE-HF evaluated 191 patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (< 35%), New York Heart Association class II-III symptoms, and who had an implanted CRT and/or ICD to develop an alert management guide to optimize medical treatment.12 It aimed to adjust patient regimen within 6 days of an elevated Heart- Logic index by either initiation, escalation, or maintenance of HF treatment depending on the index trend after the initial alert. This trial found that by focusing on such optimization, HF treatment was augmented during 74% of the 585 alert cases and during 54% of 3290 weekly alerts.

Initiation and uptitration of the 4 primary components of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) are recommended by the 2022 Heart Failure Guidelines to reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with HFrEF.2 The 4 pillars of GDMT consist of -blockers (BB), sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors (RASi) including angiotensin II receptor blocker/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) (Appendix 1). Obtaining and titrating to target doses wherever possible is recommended, as those were the doses that established safety and efficacy in patients with HFrEF in clinical trials.2 Pharmacists are adequately equipped to optimize HF GDMT and appropriately monitor drug response.

Through the use of HeartLogic in clinical practice, patients with HF have been shown to have improved clinical outcomes and are more likely to receive effective care; 80% of alerts were shown to provide new information to clinicians.13 This project sought to quantify the total number and types of pharmacist interventions driven by integration of HeartLogic index monitoring into practice.

Methods

The West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC) Research Program Office approved this project and determined it was exempt from institutional review board oversight. Patients were screened retrospectively and prospectively from May 26, 2022, through December 31, 2022, by a cardiology clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) and a cardiology pharmacy resident using the local monitoring suite for the HeartLogic-compatible device, LATITUDE NXT. Read-only access to the local monitoring suit was granted by the National Cardiac Device Surveillance Program. Training for HeartLogic was completed through continuing education courses provided by Boston Scientific. Additional information was provided by Boston Scientific representative presentations and collaboration with WPBVAMC pacemaker clinic HCPs.

Individuals included were patients with HeartLogic-capable ICDs. A HeartLogic alert had to be present at initial patient contact. Patients were also contacted as part of routine clinical practice, but no formal number or frequency of calls to patients was required. The initial contact must be with a pharmacist for the patient to be included, but subsequent contact by other HCPs was included. Patients in the cardiology clinic are required to meet with a cardiologist at least annually; however, interim visits can be completed by advanced practice registered nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, or CPPs.

Patients in alert status were contacted by telephone and appropriate modifications of HF therapy were made by the CPP based on score metrics, medical record review, and patient interview. Information surrounding the initial alert, baseline patient data, medication and monitoring interventions made, and clinical outcomes such as hospitalization, symptom improvement, follow-up, and mortality were collected. Information for each encounter was collected until 42 days from the initial date of pharmacist contact.

Clinically successful tolerability of intervention implementation was defined as tolerability, adherence, and lack of adverse effects (AEs) per patient report at follow-up or within 42 days from initial alert (Appendix 2). A decrease in dose was not counted as intolerance. A single patient may have been counted as multiple encounters if the original intervention resulted in treatment intolerance and the patient remained in alert or if an additional alert occurred after 42 days of the initial alert. There were no specific time criteria for follow-up, which occurred at the CPP’s discretion.

There was no mandated algorithm used to alter medications based on the Heart- Logic score, nor were there required minimum or maximum numbers of interventions after an alert. Patient contact by telephone initiated an encounter. The types of interventions included medication increases, decreases, initiation, discontinuation, or no medication change. Each medication change and rationale, if applicable, was recorded for the encounter ≤ 42 days after the initial contact date. If a medication with required monitoring parameters was augmented, the pharmacist was responsible for ordering laboratory testing and follow-up. Most interventions were completed by telephone; however, some patients had in-person visits in the HF CPP clinic.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the number of pharmacist interventions made to optimize GDMT, defined as either an initiation or dose increase. Key intervention analysis included the use and dosing of the 4 primary components of HF GDMT: BB, SGLT2i, MRA, and ARNi/ARB/ACEi. In addition to the 4 primary components of GDMT, loop diuretic changes were also recorded and analyzed. Secondary endpoints were the number of HF hospitalizations ≤ 42 days after the initial alert, and the effect of medication interventions on device metrics, patient symptoms, and tolerability. Successful tolerability was defined as continued use of augmented GDMT without intolerance or discontinuation. The primary analysis was analyzed through descriptive statistics. Median changes in HeartLogic scores and metrics from baseline were analyzed using a paired, 2-sided t test with an α of .05 to detect significance.

Results

There were 39 WPBVAMC patients with a HeartLogic-capable device. Twenty-one alert encounters were analyzed in 16 patients (41%) over 31 weeks of data collection. The 16 patients at baseline had a mean age of 74 years, all were male, and 12 (75%) were White. Eight patients (50%) had a recent ejection fraction (EF) between 30% and 40%. Three patients had an EF ≥ 40%. At the time of alert, 15 patients used BB (94%), 10 used loop diuretics (63%), and 9 used ARNi (56%) (Table 1).

There were 23 medication changes made during initial contact. The most common change was starting an SGLT2i (30%; n = 7), followed by starting an MRA (22%; n = 5), and increasing the ARNi dose (22%; n = 5). At the initial contact, ≥ 1 medication optimization occurred in 95% (n = 20) of encounters. The CPP contacted patients a mean of 4.8 days after the initial alert.

Patients were taking a mean of 2.6 primary GDMT medications at baseline and 3.0 at 42 days. CPP encounters led to a mean of 1.8 medication changes over the 6-week period (range, 0-5). Seventeen medications were started, 13 medications were increased, 3 medications were decreased, and 4 medications were stopped (Table 2). One ACEi and 1 ARB were switched as a therapy escalation to an ARNi. One patient was on 1 of 4 primary GDMTs at baseline, which increased to 4 GDMT agents at 42 days.

SGLT2 inhibitors were added most often at initial contact (54%) and throughout the 42-day period (41%). The most common successfully tolerated optimizations were RASi, followed by MRA, SGLT2 inhibitors, BB, and loop diuretics with 11, 6, 5, 3, and 2 patients, respectively. Interventions were tolerated by 90% of patients, and no HF hospitalization occurred during follow-up. All possible rationales for patients with the same or reduced number of GDMT at 42 days compared with baseline are shown in Appendix 2.

Device Metrics

During initial contact, the most common HeartLogic metric category that was predominantly worsening were heart sounds (S1, S3, and S3/S1 ratio), followed by compensatory mechanism sensors (NHR and RR) and congestion (impedance) at rates of 61.9%, 23.8%, and 14.3%, respectively (Figure 2).

The median HeartLogic index score was 18 at baseline and 5 at the end of the follow-up period (P < .001). The changes in score and metrics were compared with the type of successfully tolerated GDMT optimization made (Table 3). The GDMT optimization analysis included SGLT2i, RASi, MRA, BB, and loop diuretics. All interventions reduced the overall HeartLogic index score, ranging from a 9.5-point reduction (loop diuretics) to a 16-point reduction (SGLT2i and BB). Optimization of SGLT2i, RASi, and loop diuretics had a positive impact on S1 score. For S3 score, SGLT2i, MRA, and BB had a positive impact. All medications, except for SGLT2i therapy, reduced the NHR score. Optimization of MRA, SGLT2i, and BB had positive impacts on the impedance score. All medications reduced RR from baseline. Only SGLT2i and loop diuretics had positive impacts on the activity score.

Clinical Outcomes and Adverse Effects

Within 42 days of contact, 17 encounters (81%) had ≥ 1 follow-up appointment with a CPP and all 21 patients had ≥ 1 follow-up health care team member. One patient had a HF-related hospitalization within 42 days of contact; however, that individual refused the recommended medication intervention. There were 13 encounters (62%) with reported symptoms at the time of the initial alert and 10 (77%) had subjective symptom improvement at 42 days (Appendix 3).

Of 30 medication optimizations, 27 primary GDMT medications were tolerated. Two medication intolerances led to discontinuation (1 SGLT2i and 1 loop diuretic) and 1 patient never started the SGLT2i (Table 4). There was only 1 known patient who did not follow the directions to adjust their medications. That individual was included because the patient agreed to the change during the CPP visit but later reported that he had never started the SGLT2i.

Discussion

The HeartLogic tool created a bridge for patients with HF to work with CPPs as soon as possible to optimize medication therapy to reduce HF events. This study highlights an additional area of expertise and service that CPPs may offer to their specialty HF clinic team. Over 31 weeks, 21 encounters and 30 medication optimizations were completed. These interventions led to significant reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care, most of which were well tolerated.

Additional hemodynamic monitoring devices are available. Similar to HeartLogic, OptiVol is a tool embedded in select Medtronic implantable devices that monitors fluid status. 14 CardioMEMS is an implantable pulmonary artery pressure sensor used as a presymptomatic data point to alert clinicians when HF is worsening. In the CHAMPION trial, the use of CardioMEMS showed a 28% reduction in HF-related hospitalization at 6 months.15 Conversely, in the GUIDE-HF trial, monitoring with CardioMEMS did not significantly reduce the composite endpoint of mortality and total HF events.16 Therefore, remote hemodynamic monitoring has variable results and the use of these tools remains uncertain per the clinical guidelines.2

The MANAGE-HF study that contributed to the validation of the HeartLogic tool may provide a comparison with this smaller single-center project. The time to follow-up within 7 days of alert was noted in only 54% of the patients in MANAGE-HF.12 In this study, 86% of patients received follow-up within 7 days, with a mean of 4.8 days. The quick turnaround from the time of alert to intervention portrays pharmacists as readily available HCPs.

In MANAGE-HF, 89% of medication augmentation involved loop diuretics or thiazides; in our project, loop diuretics were the least frequently changed medication. Most optimizations in this project included ARNi, SGLT2i, BB, and MRA, which have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality.2 Our project included use of SGLT2i therapy to affect HeartLogic metrics, which has not been evaluated previously. SGLT2i were the most commonly initiated medication after an alert. Of the 5 tolerated SGLT2i optimization encounters, 4 were out of alert at 42 days.

SGLT2i resulted in a significant decrease in HeartLogic index score from baseline and were the only class of medication that did not produce a negative change in any metric. In this study, CPPs utilizing and acting on HeartLogic alerts led to 1 (4.8%) hospitalization with HF as the primary reason for admission and no hospitalizations as a secondary cause in 42 days, compared to 37% and 7.9% in the MANAGE-HF in 1 year, respectively. An additional screening 1 year after the initial alert found that 2 (12.5%) of 12 patients had been admitted with 1 HF hospitalization each.

A strength of this study was the ability to use HeartLogic to identify high-risk patients, provide a source of patient contact and monitoring, interpret 5 cardiac sensors, and optimize all HF GDMT, not just volume management. By focusing efforts on making patient contact and pharmacotherapy interventions with morbidity and mortality benefit, remote hemodynamic monitoring may show a clear clinical benefit and become a vital part of HF care.

Limitations

Checking for adherence and tolerance to medications were mainly patient reported if there was a CPP follow-up within 42 days, or potentially through refill history when unclear. However, this limitation is reflective of current practice where patients may have multiple clinicians working to optimize HF care and where there is reliance on patients in order to guide continued therapy. Although unable to explicitly show a reduction in HF events given lack of comparator group, the interventions made are associated with improved outcomes and thus would be expected to improve patient outcomes. Changes in vital signs were not tracked as part of this project, however the main rationale for changes made were to optimize GDMT therapy, not specifically to impact vital sign measures.

HeartLogic alerts prompted identification of high-risk patients with HF, pharmacist evaluation and outreach, patient-focused pharmacotherapy care, and beneficial patient outcomes. With only 2 cardiology CPPs checking alerts once weekly, future studies may be needed with larger samples to create algorithms and protocols to increase the clinical utility of this tool on a greater scale.

Conclusions

Cardiology CPP-led HF interventions triggered by HeartLogic alerts lead to effective patient identification, increased access to care, reductions in HeartLogic scores, improvements in symptoms, and optimization of HF care. This project demonstrates the practical utility of the HeartLogic suite in conjunction with CPP care to prioritize treatment for highrisk patients with HF in an efficient manner. The data highlight the potential value of the HeartLogic tool and a CPP in HF care to facilitate initiation and optimization of GDMT to ultimately improve the morbidity and mortality in patients with HF.

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93-e621. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e895-e1032. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

- Boehmer JP, Hariharan R, Devecchi FG, et al. A multisensor algorithm predicts heart failure events in patients with implanted devices: results from the MultiSENSE study. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017;5:216-225. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.011

- Cao M, Gardner RS, Hariharan R, et al. Ambulatory monitoring of heart sounds via an implanted device is superior to auscultation for prediction of heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2020;26:151-159. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.10.006

- Calò L, Capucci A, Santini L, et al. ICD-measured heart sounds and their correlation with echocardiographic indexes of systolic and diastolic function. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;58:95-101. doi:10.1007/s10840-019-00668

- Del Buono MG, Arena R, Borlaug BA, et al. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure: JACC state-of-the- art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2209-2225. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.072

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Rials S, Aktas M, An Q, et al. Continuous respiratory rate is superior to routine outpatient dyspnea assessment for predicting heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2018;24:S45.

- Fonarow GC, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(suppl 7):S21-S30. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.07.130

- Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:823-830. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.079

- De Ruvo E, Capucci A, Ammirati F, et al. Preliminary experience of remote management of heart failure patients with a multisensor ICD alert [abstract P1536]. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(suppl S1):370.

- Hernandez AF, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Multiple cardiac sensors for management of heart failure (MANAGE- HF) - phase I evaluation of the integration and safety of the HeartLogic multisensor algorithm in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2022;28:1245-1254. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.03.349

- Santini L, D’Onofrio A, Dello Russo A, et al. Prospective evaluation of the multisensor HeartLogic algorithm for heart failure monitoring. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:691-697. doi:10.1002/clc.23366

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Adamson PB, Abraham WT, Stevenson LW, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided heart failure management reduces 30-day readmissions. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002600. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002600

- Lindenfeld J, Zile MR, Desai AS, et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398:991-1001. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01754-2

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93-e621. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e895-e1032. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001063

- Boehmer JP, Hariharan R, Devecchi FG, et al. A multisensor algorithm predicts heart failure events in patients with implanted devices: results from the MultiSENSE study. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017;5:216-225. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.011

- Cao M, Gardner RS, Hariharan R, et al. Ambulatory monitoring of heart sounds via an implanted device is superior to auscultation for prediction of heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2020;26:151-159. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.10.006

- Calò L, Capucci A, Santini L, et al. ICD-measured heart sounds and their correlation with echocardiographic indexes of systolic and diastolic function. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;58:95-101. doi:10.1007/s10840-019-00668

- Del Buono MG, Arena R, Borlaug BA, et al. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure: JACC state-of-the- art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2209-2225. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.072

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Rials S, Aktas M, An Q, et al. Continuous respiratory rate is superior to routine outpatient dyspnea assessment for predicting heart failure events. J Card Fail. 2018;24:S45.

- Fonarow GC, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(suppl 7):S21-S30. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.07.130

- Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:823-830. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.079

- De Ruvo E, Capucci A, Ammirati F, et al. Preliminary experience of remote management of heart failure patients with a multisensor ICD alert [abstract P1536]. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(suppl S1):370.

- Hernandez AF, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Multiple cardiac sensors for management of heart failure (MANAGE- HF) - phase I evaluation of the integration and safety of the HeartLogic multisensor algorithm in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2022;28:1245-1254. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.03.349

- Santini L, D’Onofrio A, Dello Russo A, et al. Prospective evaluation of the multisensor HeartLogic algorithm for heart failure monitoring. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:691-697. doi:10.1002/clc.23366

- Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, et al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation. 2005;112:841-848. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492207

- Adamson PB, Abraham WT, Stevenson LW, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided heart failure management reduces 30-day readmissions. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002600. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002600

- Lindenfeld J, Zile MR, Desai AS, et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398:991-1001. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01754-2

Heart Failure Diagnostic Alerts to Prompt Pharmacist Evaluation and Medication Optimization

Heart Failure Diagnostic Alerts to Prompt Pharmacist Evaluation and Medication Optimization

Veterans Face Long Delays in ATTR-CM Diagnosis After HF

TOPLINE:

Veterans received a diagnosis of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) a median of 490 days after heart failure (HF) diagnosis. Those who had atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, or chronic kidney disease experienced longer diagnostic delays, whereas older or Black patients experienced shorter delays.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Veterans Health Administration to quantify the time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis and identify predictors of delays in diagnosis.

- They included veterans with HF and incident ATTR-CM diagnosed between 2016 and 2022; these veterans were identified using an algorithm based on diagnoses and medications.

- The final analysis included 2557 veterans, with a median age of 80.5 years; 99.5% were men, and 56.3% were White individuals.

- Assessments captured the time from the first HF diagnosis, the first outpatient prescription for a loop diuretic, and the first hospitalization for HF to the first ATTR-CM diagnosis, along with demographics and comorbidities.

- The primary outcome was the number of days from incident HF diagnosis to incident ATTR-CM diagnosis; a delay of > 6 months was considered meaningful.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 490 days. Overall, 65% of veterans experienced diagnostic delays > 6 months, and > 25% had delays longer than 3 years.

- Factors associated with a shorter time to ATTR-CM diagnosis included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.57-0.88) and older age (aOR per 10 years, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59-0.73).

- The likelihood of longer diagnostic delays was higher in patients with coronary artery disease (aOR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15-1.64) and chronic kidney disease (aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.50-2.15). Those with atrial fibrillation were more likely to have longer delays, although the lower bound of 95% CI was borderline (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.00-1.45).

- Among veterans with prior prescriptions of loop diuretics, the median time from the first prescription to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 835 days. Among those with a prior hospitalization for HF, the median time from hospitalization to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 300 days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study supports the need for increased testing for ATTR-CM, thorough evaluation of cardiomyopathy etiologies at the time of HF diagnosis, and the need for new interventions that shorten the diagnostic delay in ATTR-CM,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Gabriela Spencer-Bonilla, MD, MSc, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. It was published online on JACC .

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited to veterans engaged long enough for diagnoses of both HF and ATTR-CM. The findings may not be generalized to women given the predominantly male cohort. Echocardiography and ATTR subtype or genetic data were unavailable.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from AstraZeneca. Four authors reported being the employees and stockholders of AstraZeneca. Several authors reported receiving research funding, consulting fees, and/or having equity in multiple pharmaceutical and healthcare companies, including Novo Nordisk, Bridge Bio, and Pfizer. Two authors reported receiving support from the American Heart Association, with one of them also receiving support from the National Institutes of Health.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Veterans received a diagnosis of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) a median of 490 days after heart failure (HF) diagnosis. Those who had atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, or chronic kidney disease experienced longer diagnostic delays, whereas older or Black patients experienced shorter delays.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Veterans Health Administration to quantify the time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis and identify predictors of delays in diagnosis.

- They included veterans with HF and incident ATTR-CM diagnosed between 2016 and 2022; these veterans were identified using an algorithm based on diagnoses and medications.

- The final analysis included 2557 veterans, with a median age of 80.5 years; 99.5% were men, and 56.3% were White individuals.

- Assessments captured the time from the first HF diagnosis, the first outpatient prescription for a loop diuretic, and the first hospitalization for HF to the first ATTR-CM diagnosis, along with demographics and comorbidities.

- The primary outcome was the number of days from incident HF diagnosis to incident ATTR-CM diagnosis; a delay of > 6 months was considered meaningful.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 490 days. Overall, 65% of veterans experienced diagnostic delays > 6 months, and > 25% had delays longer than 3 years.

- Factors associated with a shorter time to ATTR-CM diagnosis included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.57-0.88) and older age (aOR per 10 years, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59-0.73).

- The likelihood of longer diagnostic delays was higher in patients with coronary artery disease (aOR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15-1.64) and chronic kidney disease (aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.50-2.15). Those with atrial fibrillation were more likely to have longer delays, although the lower bound of 95% CI was borderline (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.00-1.45).

- Among veterans with prior prescriptions of loop diuretics, the median time from the first prescription to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 835 days. Among those with a prior hospitalization for HF, the median time from hospitalization to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 300 days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study supports the need for increased testing for ATTR-CM, thorough evaluation of cardiomyopathy etiologies at the time of HF diagnosis, and the need for new interventions that shorten the diagnostic delay in ATTR-CM,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Gabriela Spencer-Bonilla, MD, MSc, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. It was published online on JACC .

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited to veterans engaged long enough for diagnoses of both HF and ATTR-CM. The findings may not be generalized to women given the predominantly male cohort. Echocardiography and ATTR subtype or genetic data were unavailable.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from AstraZeneca. Four authors reported being the employees and stockholders of AstraZeneca. Several authors reported receiving research funding, consulting fees, and/or having equity in multiple pharmaceutical and healthcare companies, including Novo Nordisk, Bridge Bio, and Pfizer. Two authors reported receiving support from the American Heart Association, with one of them also receiving support from the National Institutes of Health.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Veterans received a diagnosis of transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) a median of 490 days after heart failure (HF) diagnosis. Those who had atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, or chronic kidney disease experienced longer diagnostic delays, whereas older or Black patients experienced shorter delays.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the US Veterans Health Administration to quantify the time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis and identify predictors of delays in diagnosis.

- They included veterans with HF and incident ATTR-CM diagnosed between 2016 and 2022; these veterans were identified using an algorithm based on diagnoses and medications.

- The final analysis included 2557 veterans, with a median age of 80.5 years; 99.5% were men, and 56.3% were White individuals.

- Assessments captured the time from the first HF diagnosis, the first outpatient prescription for a loop diuretic, and the first hospitalization for HF to the first ATTR-CM diagnosis, along with demographics and comorbidities.

- The primary outcome was the number of days from incident HF diagnosis to incident ATTR-CM diagnosis; a delay of > 6 months was considered meaningful.

TAKEAWAY:

- The median time from HF diagnosis to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 490 days. Overall, 65% of veterans experienced diagnostic delays > 6 months, and > 25% had delays longer than 3 years.

- Factors associated with a shorter time to ATTR-CM diagnosis included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.57-0.88) and older age (aOR per 10 years, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.59-0.73).

- The likelihood of longer diagnostic delays was higher in patients with coronary artery disease (aOR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15-1.64) and chronic kidney disease (aOR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.50-2.15). Those with atrial fibrillation were more likely to have longer delays, although the lower bound of 95% CI was borderline (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.00-1.45).

- Among veterans with prior prescriptions of loop diuretics, the median time from the first prescription to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 835 days. Among those with a prior hospitalization for HF, the median time from hospitalization to ATTR-CM diagnosis was 300 days.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study supports the need for increased testing for ATTR-CM, thorough evaluation of cardiomyopathy etiologies at the time of HF diagnosis, and the need for new interventions that shorten the diagnostic delay in ATTR-CM,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Gabriela Spencer-Bonilla, MD, MSc, of Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, California. It was published online on JACC .

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis was limited to veterans engaged long enough for diagnoses of both HF and ATTR-CM. The findings may not be generalized to women given the predominantly male cohort. Echocardiography and ATTR subtype or genetic data were unavailable.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received funding from AstraZeneca. Four authors reported being the employees and stockholders of AstraZeneca. Several authors reported receiving research funding, consulting fees, and/or having equity in multiple pharmaceutical and healthcare companies, including Novo Nordisk, Bridge Bio, and Pfizer. Two authors reported receiving support from the American Heart Association, with one of them also receiving support from the National Institutes of Health.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Eosinophilic Endomyocarditis: A Rare Cardiac Manifestation

Background

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare condition caused by an overproduction of eosinophils leading to tissue infiltration and end-organ damage. HES can infiltrate the heart and lead to rare but severe cases of eosinophilic endomyocarditis, potentially causing heart failure, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and thromboembolic events.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old female presented for abdominal pain but was found to have significant leukocytosis and eosinophilia with an absolute eosinophil count of 15.50×109/L. Further imaging with cardiac MRI showed early nodular subendocardial enhancement suggestive of eosinophilic endomyocarditis. Bone marrow biopsy was negative for clonal disorders and gastric biopsy was negative for eosinophils and H. pylori. Treatment with high-dose prednisone caused reduction in eosinophils and repeat cardiac MRI showed significant improvement in endomyocarditis.

Discussion