User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Improving Colorectal Cancer Screening via Mailed Fecal Immunochemical Testing in a Veterans Affairs Health System

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

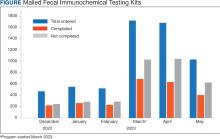

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

Program Metrics

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

Adding Protein EpiScores May Better Predict CRC Survival

Adding Protein EpiScores May Better Predict CRC Survival

DNA methylation-derived biomarkers called Protein EpiScores may improve the accuracy of disease-free and overall survival prediction in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), compared with traditional clinical risk factors alone, suggest results of a prospective study.

Although Protein EpiScores require further validation before they are ready for clinical use, the present data offer insights into the underlying processes shaping CRC outcomes, lead author Alicia R. Richards, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Epigenetics.

“The immediate value of our findings is highlighting biological pathways like immune suppression and coagulation as drivers of poor outcomes,” senior author Jacob K. Kresovich, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

What Are Protein EpiScores?

Previous studies have evaluated epigenetic clocks, which are derived from DNA methylation profiles, as markers for CRC risk. However, these clocks cannot pinpoint specific biological drivers of cancer progression, the investigators wrote.

Protein EpiScores may fill this gap; they were developed based on previous work suggesting that DNA methylation profiles may improve disease prediction based on circulating proteins (eg, C-reactive protein) and physiologic traits (eg, smoking status) beyond directly measuring those same variables.

“Protein EpiScores may therefore represent a complementary class of biomarker to direct measurements,” the investigators wrote.

Although Protein EpiScores have helped uncover biological processes driving various conditions such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, this is the first study to evaluate them specifically in the context of cancer survival.

How Did This Study Evaluate Protein EpiScores in Patients With CRC?

The present study involved 136 patients with newly diagnosed CRC from the prospective ColoCare Study.

For each patient, the investigators recorded 107 Protein EpiScores from pretreatment whole blood samples. Disease-free and overall survival were monitored over a median follow-up of 7.3 years and as long as 13.8 years. During follow-up, 26% of patients experienced disease recurrence, and 35% died.

With these data, the investigators compared the predictive power of the Protein EpiScores vs traditional clinical risk factors for disease-free and overall survival. “We used the standard factors doctors routinely collect before treatment starts to assess prognosis, including tumor stage, age at cancer diagnosis, sex, body mass index, race, and tumor location,” Kresovich said. “These are well-established predictors readily available from medical records.”

What Were the Key Findings?

Adding specific Protein EpiScores to the standard clinical risk factors significantly improved prognostic accuracy for survival.

After adjusting for confounding variables, the HCII, VEGFA, CCL17, and LGALS3BP Protein EpiScores were each independently associated with worse disease-free survival, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.62 to 1.71. Adding these scores to the clinical model improved the concordance index (C-index) from 0.64 to 0.70.

The LGALS3BP Protein EpiScore was also independently linked to overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 1.80. Adding this score to the model raised the C-index from 0.70 to 0.75.

Finally, the HCII, LGALS3BP, MMP12, and VEGFA Protein EpiScores were tied to both disease-free and overall survival with hazard ratios above 1.50.

Are These Findings Practice-Changing?

“The improvements [in prognostic accuracy] are modest but potentially meaningful and comparable to gains from other established biomarkers,” Kresovich said. “The 6-point improvement for recurrence (C-index 0.64 to 0.70) resulted in 34% of patients being reclassified into more accurate risk categories.”

In theory, this could have a meaningful clinical impact.

“In cancer care, even incremental gains matter if they prevent undertreating high-risk patients or overtreating low-risk ones,” Kresovich said.

Despite this potential, he was clear that more work is needed.

“If our findings are validated in other epidemiologic settings, these Protein EpiScores could eventually complement existing risk tools, but we’re realistically several years from clinical implementation,” Kresovich said. “We see these current findings more as a research tool that requires validation in larger cohorts before clinical use.”

How Might These Findings Shape Future Research?

Although more studies are needed before clinical rollout, the present findings point to key biological pathways, such as those involving immune suppression and coagulation, which may be driving worse outcomes in patients with CRC.

“This information can guide basic scientists and mechanistic studies to identify potential therapeutic targets,” Kresovich said.

Beyond evaluating Protein EpiScores in larger patient populations, future studies may also need to recruit a more diverse patient population, given the present cohort was 93% White.

Although the investigators noted that “the racial homogeneity reduced potential confounding by ancestry,” they also explained that “Protein EpiScores were developed in European populations, and their translation to individuals with different ancestries has not been closely examined.”

The study was supported by the Miles for Moffitt Team Science Mechanism. The investigators reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DNA methylation-derived biomarkers called Protein EpiScores may improve the accuracy of disease-free and overall survival prediction in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), compared with traditional clinical risk factors alone, suggest results of a prospective study.

Although Protein EpiScores require further validation before they are ready for clinical use, the present data offer insights into the underlying processes shaping CRC outcomes, lead author Alicia R. Richards, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Epigenetics.

“The immediate value of our findings is highlighting biological pathways like immune suppression and coagulation as drivers of poor outcomes,” senior author Jacob K. Kresovich, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

What Are Protein EpiScores?

Previous studies have evaluated epigenetic clocks, which are derived from DNA methylation profiles, as markers for CRC risk. However, these clocks cannot pinpoint specific biological drivers of cancer progression, the investigators wrote.

Protein EpiScores may fill this gap; they were developed based on previous work suggesting that DNA methylation profiles may improve disease prediction based on circulating proteins (eg, C-reactive protein) and physiologic traits (eg, smoking status) beyond directly measuring those same variables.

“Protein EpiScores may therefore represent a complementary class of biomarker to direct measurements,” the investigators wrote.

Although Protein EpiScores have helped uncover biological processes driving various conditions such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, this is the first study to evaluate them specifically in the context of cancer survival.

How Did This Study Evaluate Protein EpiScores in Patients With CRC?

The present study involved 136 patients with newly diagnosed CRC from the prospective ColoCare Study.

For each patient, the investigators recorded 107 Protein EpiScores from pretreatment whole blood samples. Disease-free and overall survival were monitored over a median follow-up of 7.3 years and as long as 13.8 years. During follow-up, 26% of patients experienced disease recurrence, and 35% died.

With these data, the investigators compared the predictive power of the Protein EpiScores vs traditional clinical risk factors for disease-free and overall survival. “We used the standard factors doctors routinely collect before treatment starts to assess prognosis, including tumor stage, age at cancer diagnosis, sex, body mass index, race, and tumor location,” Kresovich said. “These are well-established predictors readily available from medical records.”

What Were the Key Findings?

Adding specific Protein EpiScores to the standard clinical risk factors significantly improved prognostic accuracy for survival.

After adjusting for confounding variables, the HCII, VEGFA, CCL17, and LGALS3BP Protein EpiScores were each independently associated with worse disease-free survival, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.62 to 1.71. Adding these scores to the clinical model improved the concordance index (C-index) from 0.64 to 0.70.

The LGALS3BP Protein EpiScore was also independently linked to overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 1.80. Adding this score to the model raised the C-index from 0.70 to 0.75.

Finally, the HCII, LGALS3BP, MMP12, and VEGFA Protein EpiScores were tied to both disease-free and overall survival with hazard ratios above 1.50.

Are These Findings Practice-Changing?

“The improvements [in prognostic accuracy] are modest but potentially meaningful and comparable to gains from other established biomarkers,” Kresovich said. “The 6-point improvement for recurrence (C-index 0.64 to 0.70) resulted in 34% of patients being reclassified into more accurate risk categories.”

In theory, this could have a meaningful clinical impact.

“In cancer care, even incremental gains matter if they prevent undertreating high-risk patients or overtreating low-risk ones,” Kresovich said.

Despite this potential, he was clear that more work is needed.

“If our findings are validated in other epidemiologic settings, these Protein EpiScores could eventually complement existing risk tools, but we’re realistically several years from clinical implementation,” Kresovich said. “We see these current findings more as a research tool that requires validation in larger cohorts before clinical use.”

How Might These Findings Shape Future Research?

Although more studies are needed before clinical rollout, the present findings point to key biological pathways, such as those involving immune suppression and coagulation, which may be driving worse outcomes in patients with CRC.

“This information can guide basic scientists and mechanistic studies to identify potential therapeutic targets,” Kresovich said.

Beyond evaluating Protein EpiScores in larger patient populations, future studies may also need to recruit a more diverse patient population, given the present cohort was 93% White.

Although the investigators noted that “the racial homogeneity reduced potential confounding by ancestry,” they also explained that “Protein EpiScores were developed in European populations, and their translation to individuals with different ancestries has not been closely examined.”

The study was supported by the Miles for Moffitt Team Science Mechanism. The investigators reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DNA methylation-derived biomarkers called Protein EpiScores may improve the accuracy of disease-free and overall survival prediction in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC), compared with traditional clinical risk factors alone, suggest results of a prospective study.

Although Protein EpiScores require further validation before they are ready for clinical use, the present data offer insights into the underlying processes shaping CRC outcomes, lead author Alicia R. Richards, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, and colleagues wrote in Clinical Epigenetics.

“The immediate value of our findings is highlighting biological pathways like immune suppression and coagulation as drivers of poor outcomes,” senior author Jacob K. Kresovich, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center, told Medscape Medical News.

What Are Protein EpiScores?

Previous studies have evaluated epigenetic clocks, which are derived from DNA methylation profiles, as markers for CRC risk. However, these clocks cannot pinpoint specific biological drivers of cancer progression, the investigators wrote.

Protein EpiScores may fill this gap; they were developed based on previous work suggesting that DNA methylation profiles may improve disease prediction based on circulating proteins (eg, C-reactive protein) and physiologic traits (eg, smoking status) beyond directly measuring those same variables.

“Protein EpiScores may therefore represent a complementary class of biomarker to direct measurements,” the investigators wrote.

Although Protein EpiScores have helped uncover biological processes driving various conditions such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, this is the first study to evaluate them specifically in the context of cancer survival.

How Did This Study Evaluate Protein EpiScores in Patients With CRC?

The present study involved 136 patients with newly diagnosed CRC from the prospective ColoCare Study.

For each patient, the investigators recorded 107 Protein EpiScores from pretreatment whole blood samples. Disease-free and overall survival were monitored over a median follow-up of 7.3 years and as long as 13.8 years. During follow-up, 26% of patients experienced disease recurrence, and 35% died.

With these data, the investigators compared the predictive power of the Protein EpiScores vs traditional clinical risk factors for disease-free and overall survival. “We used the standard factors doctors routinely collect before treatment starts to assess prognosis, including tumor stage, age at cancer diagnosis, sex, body mass index, race, and tumor location,” Kresovich said. “These are well-established predictors readily available from medical records.”

What Were the Key Findings?

Adding specific Protein EpiScores to the standard clinical risk factors significantly improved prognostic accuracy for survival.

After adjusting for confounding variables, the HCII, VEGFA, CCL17, and LGALS3BP Protein EpiScores were each independently associated with worse disease-free survival, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.62 to 1.71. Adding these scores to the clinical model improved the concordance index (C-index) from 0.64 to 0.70.

The LGALS3BP Protein EpiScore was also independently linked to overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 1.80. Adding this score to the model raised the C-index from 0.70 to 0.75.

Finally, the HCII, LGALS3BP, MMP12, and VEGFA Protein EpiScores were tied to both disease-free and overall survival with hazard ratios above 1.50.

Are These Findings Practice-Changing?

“The improvements [in prognostic accuracy] are modest but potentially meaningful and comparable to gains from other established biomarkers,” Kresovich said. “The 6-point improvement for recurrence (C-index 0.64 to 0.70) resulted in 34% of patients being reclassified into more accurate risk categories.”

In theory, this could have a meaningful clinical impact.

“In cancer care, even incremental gains matter if they prevent undertreating high-risk patients or overtreating low-risk ones,” Kresovich said.

Despite this potential, he was clear that more work is needed.

“If our findings are validated in other epidemiologic settings, these Protein EpiScores could eventually complement existing risk tools, but we’re realistically several years from clinical implementation,” Kresovich said. “We see these current findings more as a research tool that requires validation in larger cohorts before clinical use.”

How Might These Findings Shape Future Research?

Although more studies are needed before clinical rollout, the present findings point to key biological pathways, such as those involving immune suppression and coagulation, which may be driving worse outcomes in patients with CRC.

“This information can guide basic scientists and mechanistic studies to identify potential therapeutic targets,” Kresovich said.

Beyond evaluating Protein EpiScores in larger patient populations, future studies may also need to recruit a more diverse patient population, given the present cohort was 93% White.

Although the investigators noted that “the racial homogeneity reduced potential confounding by ancestry,” they also explained that “Protein EpiScores were developed in European populations, and their translation to individuals with different ancestries has not been closely examined.”

The study was supported by the Miles for Moffitt Team Science Mechanism. The investigators reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adding Protein EpiScores May Better Predict CRC Survival

Adding Protein EpiScores May Better Predict CRC Survival

Mailed Tests Boost Colorectal Screening in Veterans

TOPLINE: Mailed fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kits with reminder phone calls promote colorectal cancer (CRC) screening among veterans without recent primary care visits. Among 782 veterans in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), mailed FITs resulted in a 26.1% screening completion rate within 6 months, compared with 5.8% for usual care and 7.7% for mailed invitations with reminders. Improving screening in this population may help CRC morbidity and mortality among veterans.

METHODOLOGY

Researchers conducted a 3-arm pragmatic RCT at the US Department of Verterans Affairs (VA) Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMC-VAMC), enrolling veterans aged 50 to 75 years without a primary care visit within 18 months.

Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to usual care (n = 260), mailed clinic-based screening invitation with reminder calls (n = 261), or mailed home FIT outreach plus prenotification letter and reminder phone calls (n = 261).

Outcome measures included documented completion of CRC screening within 6 months after randomization in the electronic health record (EHR); a secondary outcome was FIT return within 6 months among those mailed FIT.

Eligibility and exclusions were based on chart review and EHR criteria (eg, excluding symptoms, family history, inflammatory bowel disease, prior resection, or being current by having undergone a colonoscopy within 10 years, sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years, or fecal occult blood testing within 1 year).

TAKEAWAY

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 5.8% with usual care (RD, 20.3%; 95% CI, 14.3%-26.3%; RR, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.7-7.7; P < .001).

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 7.7% with mailed invitation plus reminders (RD, 18.4%; 95% CI, 12.2%-24.6%; RR, 3.4; 95% CI, 2.1-5.4; P < .001).

Screening completion does not differ between mailed invitation plus reminders (7.7%) and usual care (5.8%), and the comparison is not statistically supported (RR, 1.3; P = .39).

No statistically significant differences in screening completion are reported by age or race/ethnicity, and investigators also report no significant differences in FIT return by age or race/ethnicity in the secondary analysis.

IN PRACTICE

“This research represents the first pragmatic RCT of mailed FIT outreach screening among veterans who have not recently (18 months) used primary care services offered by the VA. In this work, there were large relative, and absolute differences in CRC screening participation rate between veterans offered home FIT screening and those who received usual care (RR = 4.52, RD = 20.2%) or a mailed invitation plus reminders (RR = 3.40, RD = 18.4%)," wrote the authors.

SOURCE

The study was led by Matthew A. Goldshore, MD, PhD, MPH, of the CMC-VAMC . It was published online in Am J Prev Med.

LIMITATIONS

The study was not able identify differences in screening completion or FIT return by patient demographic characteristics such as age and race. The sample was randomized from predominantly male veterans cared for at a single VA medical center, limiting generalizability and reducing external validity. Follow-up and subsequent evaluation of FIT-positive participants is needed for the success of a mailed FIT intervention; of the 3 FIT-positive participants who should have received follow-up evaluation, only 1 underwent colonoscopy, highlighting the challenge of FIT to colonoscopy among participants who do not use care regularly at the CMC-VAMC.

DISCLOSURES

This trial received funding from an VA Health Services Research and Development Service award, with E. Carter Paulson, MD, MSCE, and Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, serving as principal investigators. Chyke A. Doubeni received support from grant number RO1CA 213645, and Shivan J. Mehta received support from grant number K08CA 234326, both from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: Mailed fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kits with reminder phone calls promote colorectal cancer (CRC) screening among veterans without recent primary care visits. Among 782 veterans in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), mailed FITs resulted in a 26.1% screening completion rate within 6 months, compared with 5.8% for usual care and 7.7% for mailed invitations with reminders. Improving screening in this population may help CRC morbidity and mortality among veterans.

METHODOLOGY

Researchers conducted a 3-arm pragmatic RCT at the US Department of Verterans Affairs (VA) Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMC-VAMC), enrolling veterans aged 50 to 75 years without a primary care visit within 18 months.

Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to usual care (n = 260), mailed clinic-based screening invitation with reminder calls (n = 261), or mailed home FIT outreach plus prenotification letter and reminder phone calls (n = 261).

Outcome measures included documented completion of CRC screening within 6 months after randomization in the electronic health record (EHR); a secondary outcome was FIT return within 6 months among those mailed FIT.

Eligibility and exclusions were based on chart review and EHR criteria (eg, excluding symptoms, family history, inflammatory bowel disease, prior resection, or being current by having undergone a colonoscopy within 10 years, sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years, or fecal occult blood testing within 1 year).

TAKEAWAY

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 5.8% with usual care (RD, 20.3%; 95% CI, 14.3%-26.3%; RR, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.7-7.7; P < .001).

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 7.7% with mailed invitation plus reminders (RD, 18.4%; 95% CI, 12.2%-24.6%; RR, 3.4; 95% CI, 2.1-5.4; P < .001).

Screening completion does not differ between mailed invitation plus reminders (7.7%) and usual care (5.8%), and the comparison is not statistically supported (RR, 1.3; P = .39).

No statistically significant differences in screening completion are reported by age or race/ethnicity, and investigators also report no significant differences in FIT return by age or race/ethnicity in the secondary analysis.

IN PRACTICE

“This research represents the first pragmatic RCT of mailed FIT outreach screening among veterans who have not recently (18 months) used primary care services offered by the VA. In this work, there were large relative, and absolute differences in CRC screening participation rate between veterans offered home FIT screening and those who received usual care (RR = 4.52, RD = 20.2%) or a mailed invitation plus reminders (RR = 3.40, RD = 18.4%)," wrote the authors.

SOURCE

The study was led by Matthew A. Goldshore, MD, PhD, MPH, of the CMC-VAMC . It was published online in Am J Prev Med.

LIMITATIONS

The study was not able identify differences in screening completion or FIT return by patient demographic characteristics such as age and race. The sample was randomized from predominantly male veterans cared for at a single VA medical center, limiting generalizability and reducing external validity. Follow-up and subsequent evaluation of FIT-positive participants is needed for the success of a mailed FIT intervention; of the 3 FIT-positive participants who should have received follow-up evaluation, only 1 underwent colonoscopy, highlighting the challenge of FIT to colonoscopy among participants who do not use care regularly at the CMC-VAMC.

DISCLOSURES

This trial received funding from an VA Health Services Research and Development Service award, with E. Carter Paulson, MD, MSCE, and Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, serving as principal investigators. Chyke A. Doubeni received support from grant number RO1CA 213645, and Shivan J. Mehta received support from grant number K08CA 234326, both from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: Mailed fecal immunochemical test (FIT) kits with reminder phone calls promote colorectal cancer (CRC) screening among veterans without recent primary care visits. Among 782 veterans in a randomized controlled trial (RCT), mailed FITs resulted in a 26.1% screening completion rate within 6 months, compared with 5.8% for usual care and 7.7% for mailed invitations with reminders. Improving screening in this population may help CRC morbidity and mortality among veterans.

METHODOLOGY

Researchers conducted a 3-arm pragmatic RCT at the US Department of Verterans Affairs (VA) Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMC-VAMC), enrolling veterans aged 50 to 75 years without a primary care visit within 18 months.

Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to usual care (n = 260), mailed clinic-based screening invitation with reminder calls (n = 261), or mailed home FIT outreach plus prenotification letter and reminder phone calls (n = 261).

Outcome measures included documented completion of CRC screening within 6 months after randomization in the electronic health record (EHR); a secondary outcome was FIT return within 6 months among those mailed FIT.

Eligibility and exclusions were based on chart review and EHR criteria (eg, excluding symptoms, family history, inflammatory bowel disease, prior resection, or being current by having undergone a colonoscopy within 10 years, sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within 5 years, or fecal occult blood testing within 1 year).

TAKEAWAY

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 5.8% with usual care (RD, 20.3%; 95% CI, 14.3%-26.3%; RR, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.7-7.7; P < .001).

CRC screening completion within 6 months is 26.1% with mailed FIT vs 7.7% with mailed invitation plus reminders (RD, 18.4%; 95% CI, 12.2%-24.6%; RR, 3.4; 95% CI, 2.1-5.4; P < .001).

Screening completion does not differ between mailed invitation plus reminders (7.7%) and usual care (5.8%), and the comparison is not statistically supported (RR, 1.3; P = .39).

No statistically significant differences in screening completion are reported by age or race/ethnicity, and investigators also report no significant differences in FIT return by age or race/ethnicity in the secondary analysis.

IN PRACTICE

“This research represents the first pragmatic RCT of mailed FIT outreach screening among veterans who have not recently (18 months) used primary care services offered by the VA. In this work, there were large relative, and absolute differences in CRC screening participation rate between veterans offered home FIT screening and those who received usual care (RR = 4.52, RD = 20.2%) or a mailed invitation plus reminders (RR = 3.40, RD = 18.4%)," wrote the authors.

SOURCE

The study was led by Matthew A. Goldshore, MD, PhD, MPH, of the CMC-VAMC . It was published online in Am J Prev Med.

LIMITATIONS

The study was not able identify differences in screening completion or FIT return by patient demographic characteristics such as age and race. The sample was randomized from predominantly male veterans cared for at a single VA medical center, limiting generalizability and reducing external validity. Follow-up and subsequent evaluation of FIT-positive participants is needed for the success of a mailed FIT intervention; of the 3 FIT-positive participants who should have received follow-up evaluation, only 1 underwent colonoscopy, highlighting the challenge of FIT to colonoscopy among participants who do not use care regularly at the CMC-VAMC.

DISCLOSURES

This trial received funding from an VA Health Services Research and Development Service award, with E. Carter Paulson, MD, MSCE, and Chyke A. Doubeni, MD, MPH, serving as principal investigators. Chyke A. Doubeni received support from grant number RO1CA 213645, and Shivan J. Mehta received support from grant number K08CA 234326, both from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no financial disclosures.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

US Cancer Institute Studying Ivermectin's 'Ability to Kill Cancer Cells'

US Cancer Institute Studying Ivermectin's 'Ability to Kill Cancer Cells'

The National Cancer Institute (NCI), the federal research agency charged with leading the war against the nation’s second-largest killer, is studying ivermectin as a potential cancer treatment, according to its top official.

“There are enough reports of it, enough interest in it, that we actually did — ivermectin, in particular — did engage in sort of a better preclinical study of its properties and its ability to kill cancer cells,” said Anthony Letai, a physician the Trump administration appointed as NCI director in September.

Letai did not cite new evidence that might have prompted the institute to research the effectiveness of the antiparasitic drug against cancer. The drug, largely used to treat people or animals for infections caused by parasites, is a popular dewormer for horses.

“We’ll probably have those results in a few months,” Letai said. “So we are taking it seriously.”

He spoke about ivermectin at a January 30 event, “Reclaiming Science: The People’s NIH,” with National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Jay Bhattacharya and other senior agency officials at Washington, DC’s Willard Hotel. The MAHA Institute hosted the discussion, framed by the “Make America Healthy Again” agenda of Health and Human Services (HSS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The National Cancer Institute is the largest of the NIH’s 27 branches.

During the COVID pandemic, ivermectin’s popularity surged as fringe medical groups promoted it as an effective treatment. Clinical trials have found it isn’t effective against COVID.

Ivermectin has become a symbol of resistance against the medical establishment among MAHA adherents and conservatives. Like-minded commentators and wellness and other online influencers have hyped — without evidence — ivermectin as a miracle cure for a host of diseases, including cancer. Trump officials have pointed to research on ivermectin as an example of the administration’s receptiveness to ideas the scientific establishment has rejected.

“If lots of people believe it and it’s moving public health, we as NIH have an obligation, again, to treat it seriously,” Bhattacharya said at the event. According to The Chronicle at Duke University, Bhattacharya recently said he wants the NIH to be “the research arm of MAHA.”

The decision by the world’s premier cancer research institute to study ivermectin as a cancer treatment has alarmed career scientists at the agency.

“I am shocked and appalled,” one NCI scientist said. “We are moving funds away from so much promising research in order to do a preclinical study based on nonscientific ideas. It’s absurd.”

KFF Health News granted the scientist and other NCI workers anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the press and fear retaliation.

HHS and the National Cancer Institute did not answer KFF Health News’ questions on the amount of money the cancer institute is spending on the study, who is carrying it out, and whether there was new evidence that prompted NCI to look into ivermectin as an anticancer therapy. Emily Hilliard, an HHS spokesperson, said NIH is dedicated to “rigorous, gold-standard research,” something the administration has repeatedly professed.

A preclinical study is an early phase of research conducted in a lab to test whether a drug or treatment may be useful and to assess potential harms. These studies take place before human clinical trials.

The scientist questioned whether there is enough initial evidence to warrant NCI’s spending of taxpayer funds to investigate the drug’s potential as a cancer treatment.

The FDA has approved ivermectin for certain uses in humans and animals. Tablets are used to treat conditions caused by parasitic worms, and the FDA has approved ivermectin lotions to treat lice and rosacea. Two scientists involved in its discovery won the Nobel Prize in 2015, tied to the drug’s success in treating certain parasitic diseases.

The FDA has warned that large doses of ivermectin can be dangerous. Overdoses can cause seizures, comas, or death.

Kennedy, supporters of the MAHA movement, and some conservative commentators have promoted the idea that the government and pharmaceutical companies quashed ivermectin and other inexpensive, off-patent drugs because they’re not profitable for the drug industry.

“FDA’s war on public health is about to end,” Kennedy wrote in an October 2024 X post that has since gone viral. “This includes its aggressive suppression of psychedelics, peptides, stem cells, raw milk, hyperbaric therapies, chelating compounds, ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, vitamins, clean foods, sunshine, exercise, nutraceuticals and anything else that advances human health and can’t be patented by Pharma.”

Previous laboratory research has shown that ivermectin could have anticancer effects because it promotes cell death and inhibits the growth of tumor cells. “It actually has been studied both with NIH funds and outside of NIH funds,” Letai said.

However, there is no evidence that ivermectin is safe and effective in treating cancer in humans. Preliminary data from a small clinical trial that gave ivermectin to patients with one type of metastatic breast cancer, in combination with immunotherapy, found no significant benefit from the addition of ivermectin.

Some physicians are concerned that patients will delay or forgo effective cancer treatments, or be harmed in other ways, if they believe unfounded claims that ivermectin can treat their disease.

“Many, many, many things work in a test tube. Quite a few things work in a mouse or a monkey. It still doesn’t mean it’s going to work in people,” said Jeffery Edenfield, executive medical director of oncology for the South Carolina-based Prisma Health Cancer Institute.

Edenfield said cancer patients ask him about ivermectin “regularly,” mostly because of what they see on social media. He said he persuaded a patient to stop using it, and a colleague recently had a patient who decided “to forgo highly effective standard therapy in favor of ivermectin.”

“People come to the discussion having largely already made up their mind,” Edenfield said. “We’re in this delicate time when there’s sort of a fundamental mistrust of medicine,” he added. “Some people are just not going to believe me. I just have to keep trying.”

A June letter by clinicians at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio detailed how an adolescent patient with metastatic bone cancer started taking ivermectin “after encountering social media posts touting its benefits.” The patient — who hadn’t been given a prescription by a clinician — experienced ivermectin-related neurotoxicity and had to seek emergency care because of nausea, fatigue, and other symptoms.

“We urge the pediatric oncology community to advocate for sensible health policy that prioritizes the well-being of our patients,” the clinicians wrote. The lack of evidence about ivermectin and cancer hasn’t stopped celebrities and online influencers from promoting the notion that the drug is a cure-all. On a January 2025 episode of Joe Rogan’s podcast, actor Mel Gibson claimed that a combination of drugs that included ivermectin cured 3friends with stage IV cancer. The episode has been viewed > 12 million times.

Lawmakers in a handful of states have made the drug available over the counter. And Florida — which, under Republican Governor Ron DeSantis, has become a hotbed for anti-vaccine policies and the spread of public health misinformation — announced last fall that the state plans to fund research to study the drug as a potential cancer treatment.

The Florida Department of Health did not respond to questions about that effort.

Letai, previously a Dana-Farber Cancer Institute oncologist, started at the National Cancer Institute after months of upheaval caused by Trump administration policies.

“What you’re hearing at the NIH now is an openness to ideas — even ideas that scientists would say, ‘Oh, there’s no way it could work’ — but nevertheless applying rigorous scientific methods to those ideas,” Bhattacharya said at the January 30 event.

A second NCI scientist, who was granted anonymity due to fear of retaliation, said the notion that NIH was not open to investigating the value of off-label drugs in cancer is “ridiculous.”

“This is not a new idea they came up with,” the scientist said.

Letai didn’t elaborate on whether NCI scientists are conducting the research or if it has directed funding to an outside institution. Three-fourths of the cancer institute’s research dollars go to outside scientists.

He also aimed to temper expectations.

“At least on a population level,” Letai said, “it’s not going to be a cure-all for cancer.”

The National Cancer Institute (NCI), the federal research agency charged with leading the war against the nation’s second-largest killer, is studying ivermectin as a potential cancer treatment, according to its top official.

“There are enough reports of it, enough interest in it, that we actually did — ivermectin, in particular — did engage in sort of a better preclinical study of its properties and its ability to kill cancer cells,” said Anthony Letai, a physician the Trump administration appointed as NCI director in September.

Letai did not cite new evidence that might have prompted the institute to research the effectiveness of the antiparasitic drug against cancer. The drug, largely used to treat people or animals for infections caused by parasites, is a popular dewormer for horses.

“We’ll probably have those results in a few months,” Letai said. “So we are taking it seriously.”

He spoke about ivermectin at a January 30 event, “Reclaiming Science: The People’s NIH,” with National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Jay Bhattacharya and other senior agency officials at Washington, DC’s Willard Hotel. The MAHA Institute hosted the discussion, framed by the “Make America Healthy Again” agenda of Health and Human Services (HSS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The National Cancer Institute is the largest of the NIH’s 27 branches.

During the COVID pandemic, ivermectin’s popularity surged as fringe medical groups promoted it as an effective treatment. Clinical trials have found it isn’t effective against COVID.

Ivermectin has become a symbol of resistance against the medical establishment among MAHA adherents and conservatives. Like-minded commentators and wellness and other online influencers have hyped — without evidence — ivermectin as a miracle cure for a host of diseases, including cancer. Trump officials have pointed to research on ivermectin as an example of the administration’s receptiveness to ideas the scientific establishment has rejected.

“If lots of people believe it and it’s moving public health, we as NIH have an obligation, again, to treat it seriously,” Bhattacharya said at the event. According to The Chronicle at Duke University, Bhattacharya recently said he wants the NIH to be “the research arm of MAHA.”

The decision by the world’s premier cancer research institute to study ivermectin as a cancer treatment has alarmed career scientists at the agency.

“I am shocked and appalled,” one NCI scientist said. “We are moving funds away from so much promising research in order to do a preclinical study based on nonscientific ideas. It’s absurd.”

KFF Health News granted the scientist and other NCI workers anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the press and fear retaliation.

HHS and the National Cancer Institute did not answer KFF Health News’ questions on the amount of money the cancer institute is spending on the study, who is carrying it out, and whether there was new evidence that prompted NCI to look into ivermectin as an anticancer therapy. Emily Hilliard, an HHS spokesperson, said NIH is dedicated to “rigorous, gold-standard research,” something the administration has repeatedly professed.

A preclinical study is an early phase of research conducted in a lab to test whether a drug or treatment may be useful and to assess potential harms. These studies take place before human clinical trials.

The scientist questioned whether there is enough initial evidence to warrant NCI’s spending of taxpayer funds to investigate the drug’s potential as a cancer treatment.

The FDA has approved ivermectin for certain uses in humans and animals. Tablets are used to treat conditions caused by parasitic worms, and the FDA has approved ivermectin lotions to treat lice and rosacea. Two scientists involved in its discovery won the Nobel Prize in 2015, tied to the drug’s success in treating certain parasitic diseases.

The FDA has warned that large doses of ivermectin can be dangerous. Overdoses can cause seizures, comas, or death.

Kennedy, supporters of the MAHA movement, and some conservative commentators have promoted the idea that the government and pharmaceutical companies quashed ivermectin and other inexpensive, off-patent drugs because they’re not profitable for the drug industry.

“FDA’s war on public health is about to end,” Kennedy wrote in an October 2024 X post that has since gone viral. “This includes its aggressive suppression of psychedelics, peptides, stem cells, raw milk, hyperbaric therapies, chelating compounds, ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, vitamins, clean foods, sunshine, exercise, nutraceuticals and anything else that advances human health and can’t be patented by Pharma.”

Previous laboratory research has shown that ivermectin could have anticancer effects because it promotes cell death and inhibits the growth of tumor cells. “It actually has been studied both with NIH funds and outside of NIH funds,” Letai said.

However, there is no evidence that ivermectin is safe and effective in treating cancer in humans. Preliminary data from a small clinical trial that gave ivermectin to patients with one type of metastatic breast cancer, in combination with immunotherapy, found no significant benefit from the addition of ivermectin.

Some physicians are concerned that patients will delay or forgo effective cancer treatments, or be harmed in other ways, if they believe unfounded claims that ivermectin can treat their disease.

“Many, many, many things work in a test tube. Quite a few things work in a mouse or a monkey. It still doesn’t mean it’s going to work in people,” said Jeffery Edenfield, executive medical director of oncology for the South Carolina-based Prisma Health Cancer Institute.

Edenfield said cancer patients ask him about ivermectin “regularly,” mostly because of what they see on social media. He said he persuaded a patient to stop using it, and a colleague recently had a patient who decided “to forgo highly effective standard therapy in favor of ivermectin.”

“People come to the discussion having largely already made up their mind,” Edenfield said. “We’re in this delicate time when there’s sort of a fundamental mistrust of medicine,” he added. “Some people are just not going to believe me. I just have to keep trying.”