User login

‘Practice-changing’ treatments emerging in AML

NEW YORK—We are “finally” making progress in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

Jessica K. Altman, MD, said a number of developments have resulted in improved AML treatment, including a better understanding of biology and prognostic assessment, continued advances in transplant, and updating standard treatments and incorporating novel agents in both relapsed/refractory and newly diagnosed patients.

“There are a couple of practice-changing treatments in acute myeloid leukemia, 2 of which happened over the last decade: daunorubicin intensification and the use of FLT3 inhibitors,” said Dr Altman, an associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

Dr Altman went on to explain that novel therapies for AML can be divided into 2 basic categories. There are agents that don’t depend on mutation status (like daunorubicin) and those that are mutation-specific (like FLT3 inhibitors).

Therapies not dependent on mutational complexity

The therapies that are not dependent on mutational complexity include anti-CD33 antibodies, BCL‐2 inhibitors, a dose-intensified anthracycline regimen, and different formulations of 7+3, including CPX‐351.

Escalated daunorubicin

Randomized trials of escalated daunorubicin (90 vs 45 mg/m2) have demonstrated benefit in complete responses (CRs) and overall survival (OS) in intermediate-risk patients and patients with core-binding factor mutation. They have demonstrated benefit in OS in FLT3 ITD+ patients.

In patients up to 65 years of age, 60–90 mg/m2 of daunorubicin is now standard.

“It’s still not clear to me—and I don’t know if it ever will be—if 90 is equivalent to 60,” Dr Altman said.

CPX-351

CPX-351 is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin. In a randomized, phase 3 study of older adults with secondary AML, the median OS was 9.56 months for patients treated with CPX-351 and 5.95 months for patients on the 7+3 regimen (P=0.005).

The median event-free survival was significantly better with CPX-351 (P=0.021), as was the rate of CR + CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi). The rate of CR + CRi was 47.7% with CPX-351 and 33.3% for 7+3 (P=0.016).

A similar number of patients went on to transplant in each arm. Grade 3-5 adverse events were similar in frequency and severity in both arms—92% with CPX-351 vs 91% with 7+3.

SGN-CD33A

CD33 is not a new target in myeloid leukemia, Dr Altman pointed out. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin has been studied, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and then withdrawn.

However, an increasing number of studies with gemtuzumab are underway, she said, and the agent may once again have a place in the AML armamentarium.

The newest CD33 construct is SGN-CD33A, a stable dipeptide linker that enables uniform drug loading of a pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer that crosslinks DNA and leads to cell death.

“Single-agent data was quite promising,” Dr Altman noted, with a CR + CRi rate of 41% in previously treated patients and 58% in 12 treatment-naïve patients.

These results prompted a combination study of SGN-CD33A with hypomethylating agents.

“Results were higher than expected with a hypomethylating agent,” Dr Altman pointed out.

The CR + CRi + CR with incomplete platelet recovery was 58%. And the median relapse-free survival was 7.7 months.

A phase 3 randomized trial of SGN-CD33A is planned.

Venetoclax

BCL-2 inhibitors are the fourth type of agent not dependent on mutation complexity. Venetoclax (ABT‐199) is a small‐molecule BCL-2 inhibitor that leads to the initiation of apoptosis.

In a phase 1b trial of venetoclax in combination with a hypomethylating agent, the overall CR rate was 35%, and the CRi rate was 35%.

“Again, higher than what would be expected with a hypomethylating agent alone,” Dr Altman said.

In a phase 1b/2 trial of venetoclax in combination with low‐dose cytarabine, the CR + CRi rate was 54%. Patients responded even if they had prior exposure to hypomethylating agents.

Mutation-specific novel agents

The FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin and the IDH inhibitors AG-120 and AG-221 are among the most exciting mutation-specific agents and the ones most progressed, according to Dr Altman.

FLT3-ITD is mutated in about 30% of AML patients and carries an unfavorable prognosis, and the IDH mutation occurs in about 10% and confers a favorable prognosis.

Midostaurin

A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of daunorubicin/cytarabine induction and high-dose cytarabine consolidation with midostaurin (PKC412) or placebo had a 59% CR rate by day 60 in the midostaurin arm, compared with 53% in the placebo arm.

“The CR rate was slightly higher in the midostaurin arm,” Dr Altman said, “but what’s the most remarkable about this study is the difference in overall survival.”

The median OS in the midostaurin arm was 74.7 months, compared with 25.6 months in the placebo arm (P=0.0074).

“The major take-home message from this clinical trial,” Dr Altman said, “is that midostaurin improved the overall survival when added to standard therapy and represents a new standard of care.”

AG-120 and AG-221

Two IDH inhibitors that have substantial data available are the IDH1 inhibitor AG-120 and the IDH2 inhibitor AG-221.

As of October 2015, 78 patients had been treated with AG-120 in a phase 1 trial, yielding an overall response rate of 35% and a CR rate of 15%.

As of September 2015, 209 patients had been treated with AG-221 in a phase 1/2 trial, and 66 are still on study. The overall response rate was 37% in 159 adults with relapsed/refractory AML, with a median duration of response of 6.9 months. The CR rate was 18%.

Investigators have initiated a phase 3 study of AG-221 compared to conventional care regimens. ![]()

NEW YORK—We are “finally” making progress in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

Jessica K. Altman, MD, said a number of developments have resulted in improved AML treatment, including a better understanding of biology and prognostic assessment, continued advances in transplant, and updating standard treatments and incorporating novel agents in both relapsed/refractory and newly diagnosed patients.

“There are a couple of practice-changing treatments in acute myeloid leukemia, 2 of which happened over the last decade: daunorubicin intensification and the use of FLT3 inhibitors,” said Dr Altman, an associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

Dr Altman went on to explain that novel therapies for AML can be divided into 2 basic categories. There are agents that don’t depend on mutation status (like daunorubicin) and those that are mutation-specific (like FLT3 inhibitors).

Therapies not dependent on mutational complexity

The therapies that are not dependent on mutational complexity include anti-CD33 antibodies, BCL‐2 inhibitors, a dose-intensified anthracycline regimen, and different formulations of 7+3, including CPX‐351.

Escalated daunorubicin

Randomized trials of escalated daunorubicin (90 vs 45 mg/m2) have demonstrated benefit in complete responses (CRs) and overall survival (OS) in intermediate-risk patients and patients with core-binding factor mutation. They have demonstrated benefit in OS in FLT3 ITD+ patients.

In patients up to 65 years of age, 60–90 mg/m2 of daunorubicin is now standard.

“It’s still not clear to me—and I don’t know if it ever will be—if 90 is equivalent to 60,” Dr Altman said.

CPX-351

CPX-351 is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin. In a randomized, phase 3 study of older adults with secondary AML, the median OS was 9.56 months for patients treated with CPX-351 and 5.95 months for patients on the 7+3 regimen (P=0.005).

The median event-free survival was significantly better with CPX-351 (P=0.021), as was the rate of CR + CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi). The rate of CR + CRi was 47.7% with CPX-351 and 33.3% for 7+3 (P=0.016).

A similar number of patients went on to transplant in each arm. Grade 3-5 adverse events were similar in frequency and severity in both arms—92% with CPX-351 vs 91% with 7+3.

SGN-CD33A

CD33 is not a new target in myeloid leukemia, Dr Altman pointed out. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin has been studied, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and then withdrawn.

However, an increasing number of studies with gemtuzumab are underway, she said, and the agent may once again have a place in the AML armamentarium.

The newest CD33 construct is SGN-CD33A, a stable dipeptide linker that enables uniform drug loading of a pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer that crosslinks DNA and leads to cell death.

“Single-agent data was quite promising,” Dr Altman noted, with a CR + CRi rate of 41% in previously treated patients and 58% in 12 treatment-naïve patients.

These results prompted a combination study of SGN-CD33A with hypomethylating agents.

“Results were higher than expected with a hypomethylating agent,” Dr Altman pointed out.

The CR + CRi + CR with incomplete platelet recovery was 58%. And the median relapse-free survival was 7.7 months.

A phase 3 randomized trial of SGN-CD33A is planned.

Venetoclax

BCL-2 inhibitors are the fourth type of agent not dependent on mutation complexity. Venetoclax (ABT‐199) is a small‐molecule BCL-2 inhibitor that leads to the initiation of apoptosis.

In a phase 1b trial of venetoclax in combination with a hypomethylating agent, the overall CR rate was 35%, and the CRi rate was 35%.

“Again, higher than what would be expected with a hypomethylating agent alone,” Dr Altman said.

In a phase 1b/2 trial of venetoclax in combination with low‐dose cytarabine, the CR + CRi rate was 54%. Patients responded even if they had prior exposure to hypomethylating agents.

Mutation-specific novel agents

The FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin and the IDH inhibitors AG-120 and AG-221 are among the most exciting mutation-specific agents and the ones most progressed, according to Dr Altman.

FLT3-ITD is mutated in about 30% of AML patients and carries an unfavorable prognosis, and the IDH mutation occurs in about 10% and confers a favorable prognosis.

Midostaurin

A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of daunorubicin/cytarabine induction and high-dose cytarabine consolidation with midostaurin (PKC412) or placebo had a 59% CR rate by day 60 in the midostaurin arm, compared with 53% in the placebo arm.

“The CR rate was slightly higher in the midostaurin arm,” Dr Altman said, “but what’s the most remarkable about this study is the difference in overall survival.”

The median OS in the midostaurin arm was 74.7 months, compared with 25.6 months in the placebo arm (P=0.0074).

“The major take-home message from this clinical trial,” Dr Altman said, “is that midostaurin improved the overall survival when added to standard therapy and represents a new standard of care.”

AG-120 and AG-221

Two IDH inhibitors that have substantial data available are the IDH1 inhibitor AG-120 and the IDH2 inhibitor AG-221.

As of October 2015, 78 patients had been treated with AG-120 in a phase 1 trial, yielding an overall response rate of 35% and a CR rate of 15%.

As of September 2015, 209 patients had been treated with AG-221 in a phase 1/2 trial, and 66 are still on study. The overall response rate was 37% in 159 adults with relapsed/refractory AML, with a median duration of response of 6.9 months. The CR rate was 18%.

Investigators have initiated a phase 3 study of AG-221 compared to conventional care regimens. ![]()

NEW YORK—We are “finally” making progress in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

Jessica K. Altman, MD, said a number of developments have resulted in improved AML treatment, including a better understanding of biology and prognostic assessment, continued advances in transplant, and updating standard treatments and incorporating novel agents in both relapsed/refractory and newly diagnosed patients.

“There are a couple of practice-changing treatments in acute myeloid leukemia, 2 of which happened over the last decade: daunorubicin intensification and the use of FLT3 inhibitors,” said Dr Altman, an associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

Dr Altman went on to explain that novel therapies for AML can be divided into 2 basic categories. There are agents that don’t depend on mutation status (like daunorubicin) and those that are mutation-specific (like FLT3 inhibitors).

Therapies not dependent on mutational complexity

The therapies that are not dependent on mutational complexity include anti-CD33 antibodies, BCL‐2 inhibitors, a dose-intensified anthracycline regimen, and different formulations of 7+3, including CPX‐351.

Escalated daunorubicin

Randomized trials of escalated daunorubicin (90 vs 45 mg/m2) have demonstrated benefit in complete responses (CRs) and overall survival (OS) in intermediate-risk patients and patients with core-binding factor mutation. They have demonstrated benefit in OS in FLT3 ITD+ patients.

In patients up to 65 years of age, 60–90 mg/m2 of daunorubicin is now standard.

“It’s still not clear to me—and I don’t know if it ever will be—if 90 is equivalent to 60,” Dr Altman said.

CPX-351

CPX-351 is a liposomal formulation of cytarabine and daunorubicin. In a randomized, phase 3 study of older adults with secondary AML, the median OS was 9.56 months for patients treated with CPX-351 and 5.95 months for patients on the 7+3 regimen (P=0.005).

The median event-free survival was significantly better with CPX-351 (P=0.021), as was the rate of CR + CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi). The rate of CR + CRi was 47.7% with CPX-351 and 33.3% for 7+3 (P=0.016).

A similar number of patients went on to transplant in each arm. Grade 3-5 adverse events were similar in frequency and severity in both arms—92% with CPX-351 vs 91% with 7+3.

SGN-CD33A

CD33 is not a new target in myeloid leukemia, Dr Altman pointed out. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin has been studied, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and then withdrawn.

However, an increasing number of studies with gemtuzumab are underway, she said, and the agent may once again have a place in the AML armamentarium.

The newest CD33 construct is SGN-CD33A, a stable dipeptide linker that enables uniform drug loading of a pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer that crosslinks DNA and leads to cell death.

“Single-agent data was quite promising,” Dr Altman noted, with a CR + CRi rate of 41% in previously treated patients and 58% in 12 treatment-naïve patients.

These results prompted a combination study of SGN-CD33A with hypomethylating agents.

“Results were higher than expected with a hypomethylating agent,” Dr Altman pointed out.

The CR + CRi + CR with incomplete platelet recovery was 58%. And the median relapse-free survival was 7.7 months.

A phase 3 randomized trial of SGN-CD33A is planned.

Venetoclax

BCL-2 inhibitors are the fourth type of agent not dependent on mutation complexity. Venetoclax (ABT‐199) is a small‐molecule BCL-2 inhibitor that leads to the initiation of apoptosis.

In a phase 1b trial of venetoclax in combination with a hypomethylating agent, the overall CR rate was 35%, and the CRi rate was 35%.

“Again, higher than what would be expected with a hypomethylating agent alone,” Dr Altman said.

In a phase 1b/2 trial of venetoclax in combination with low‐dose cytarabine, the CR + CRi rate was 54%. Patients responded even if they had prior exposure to hypomethylating agents.

Mutation-specific novel agents

The FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin and the IDH inhibitors AG-120 and AG-221 are among the most exciting mutation-specific agents and the ones most progressed, according to Dr Altman.

FLT3-ITD is mutated in about 30% of AML patients and carries an unfavorable prognosis, and the IDH mutation occurs in about 10% and confers a favorable prognosis.

Midostaurin

A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study of daunorubicin/cytarabine induction and high-dose cytarabine consolidation with midostaurin (PKC412) or placebo had a 59% CR rate by day 60 in the midostaurin arm, compared with 53% in the placebo arm.

“The CR rate was slightly higher in the midostaurin arm,” Dr Altman said, “but what’s the most remarkable about this study is the difference in overall survival.”

The median OS in the midostaurin arm was 74.7 months, compared with 25.6 months in the placebo arm (P=0.0074).

“The major take-home message from this clinical trial,” Dr Altman said, “is that midostaurin improved the overall survival when added to standard therapy and represents a new standard of care.”

AG-120 and AG-221

Two IDH inhibitors that have substantial data available are the IDH1 inhibitor AG-120 and the IDH2 inhibitor AG-221.

As of October 2015, 78 patients had been treated with AG-120 in a phase 1 trial, yielding an overall response rate of 35% and a CR rate of 15%.

As of September 2015, 209 patients had been treated with AG-221 in a phase 1/2 trial, and 66 are still on study. The overall response rate was 37% in 159 adults with relapsed/refractory AML, with a median duration of response of 6.9 months. The CR rate was 18%.

Investigators have initiated a phase 3 study of AG-221 compared to conventional care regimens. ![]()

Drug granted conditional approval to treat CLL in Canada

of venetoclax (Venclexta)

Photo courtesy of AbbVie

Health Canada has issued a Notice of Compliance with Conditions (NOC/c) for the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (Venclexta™).

This means venetoclax is conditionally approved for use in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have 17p deletion or no other available treatment options.

An NOC/c is authorization to market a drug with the condition that the sponsor perform additional studies to verify a clinical benefit.

The NOC/c policy is designed to provide access to:

- Drugs that can treat serious, life-threatening, or severely debilitating diseases

- Drugs that can treat conditions for which no drug is currently marketed in Canada

- Drugs that provide a significant increase in efficacy or significant decrease in risk when compared to existing drugs marketed in Canada.

Venetoclax (previously ABT‐199) is being developed by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. The drug is jointly commercialized by the companies in the US and by AbbVie outside of the US.

Venetoclax is currently under evaluation in phase 3 trials for the treatment of relapsed, refractory, and previously untreated CLL.

Phase 2 trial

Results from a phase 2 trial of venetoclax in CLL (M13-982, NCT01889186) were published in The Lancet Oncology in June. The trial enrolled 107 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL and 17p deletion.

Patients received venetoclax at 400 mg once daily following a weekly ramp-up schedule for the first 5 weeks. The primary endpoint was overall response rate, as determined by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 85 patients had responded to treatment, for an overall response rate of 79%.

Eight patients (8%) achieved a complete response or complete response with incomplete count recovery, 3 (3%) had a near-partial response, and 74 (69%) had a partial response. Twenty-two patients (21%) did not respond.

At the time of analysis, the median duration of response had not been reached. The same was true for progression-free survival and overall survival. The progression-free survival estimate for 12 months was 72%, and the overall survival estimate was 87%.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse was 96%. The most frequent grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (40%), infection (20%), anemia (18%), and thrombocytopenia (15%).

The incidence of serious adverse events was 55%. The most common of these events were pyrexia (7%), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (7%), pneumonia (6%), and febrile neutropenia (5%).

Grade 3 laboratory tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) was reported in 5 patients during the ramp-up period only. Three of these patients continued on venetoclax, but 2 patients required a dose interruption of 1 day each.

In the past, TLS has caused deaths in patients receiving venetoclax. In response, AbbVie stopped dose-escalation in patients receiving the drug and suspended enrollment in phase 1 trials.

However, researchers subsequently found that a modified dosing schedule, prophylaxis, and patient monitoring can reduce the risk of TLS. ![]()

of venetoclax (Venclexta)

Photo courtesy of AbbVie

Health Canada has issued a Notice of Compliance with Conditions (NOC/c) for the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (Venclexta™).

This means venetoclax is conditionally approved for use in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have 17p deletion or no other available treatment options.

An NOC/c is authorization to market a drug with the condition that the sponsor perform additional studies to verify a clinical benefit.

The NOC/c policy is designed to provide access to:

- Drugs that can treat serious, life-threatening, or severely debilitating diseases

- Drugs that can treat conditions for which no drug is currently marketed in Canada

- Drugs that provide a significant increase in efficacy or significant decrease in risk when compared to existing drugs marketed in Canada.

Venetoclax (previously ABT‐199) is being developed by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. The drug is jointly commercialized by the companies in the US and by AbbVie outside of the US.

Venetoclax is currently under evaluation in phase 3 trials for the treatment of relapsed, refractory, and previously untreated CLL.

Phase 2 trial

Results from a phase 2 trial of venetoclax in CLL (M13-982, NCT01889186) were published in The Lancet Oncology in June. The trial enrolled 107 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL and 17p deletion.

Patients received venetoclax at 400 mg once daily following a weekly ramp-up schedule for the first 5 weeks. The primary endpoint was overall response rate, as determined by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 85 patients had responded to treatment, for an overall response rate of 79%.

Eight patients (8%) achieved a complete response or complete response with incomplete count recovery, 3 (3%) had a near-partial response, and 74 (69%) had a partial response. Twenty-two patients (21%) did not respond.

At the time of analysis, the median duration of response had not been reached. The same was true for progression-free survival and overall survival. The progression-free survival estimate for 12 months was 72%, and the overall survival estimate was 87%.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse was 96%. The most frequent grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (40%), infection (20%), anemia (18%), and thrombocytopenia (15%).

The incidence of serious adverse events was 55%. The most common of these events were pyrexia (7%), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (7%), pneumonia (6%), and febrile neutropenia (5%).

Grade 3 laboratory tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) was reported in 5 patients during the ramp-up period only. Three of these patients continued on venetoclax, but 2 patients required a dose interruption of 1 day each.

In the past, TLS has caused deaths in patients receiving venetoclax. In response, AbbVie stopped dose-escalation in patients receiving the drug and suspended enrollment in phase 1 trials.

However, researchers subsequently found that a modified dosing schedule, prophylaxis, and patient monitoring can reduce the risk of TLS. ![]()

of venetoclax (Venclexta)

Photo courtesy of AbbVie

Health Canada has issued a Notice of Compliance with Conditions (NOC/c) for the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (Venclexta™).

This means venetoclax is conditionally approved for use in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have 17p deletion or no other available treatment options.

An NOC/c is authorization to market a drug with the condition that the sponsor perform additional studies to verify a clinical benefit.

The NOC/c policy is designed to provide access to:

- Drugs that can treat serious, life-threatening, or severely debilitating diseases

- Drugs that can treat conditions for which no drug is currently marketed in Canada

- Drugs that provide a significant increase in efficacy or significant decrease in risk when compared to existing drugs marketed in Canada.

Venetoclax (previously ABT‐199) is being developed by AbbVie and Genentech, a member of the Roche Group. The drug is jointly commercialized by the companies in the US and by AbbVie outside of the US.

Venetoclax is currently under evaluation in phase 3 trials for the treatment of relapsed, refractory, and previously untreated CLL.

Phase 2 trial

Results from a phase 2 trial of venetoclax in CLL (M13-982, NCT01889186) were published in The Lancet Oncology in June. The trial enrolled 107 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL and 17p deletion.

Patients received venetoclax at 400 mg once daily following a weekly ramp-up schedule for the first 5 weeks. The primary endpoint was overall response rate, as determined by an independent review committee.

At a median follow-up of 12.1 months, 85 patients had responded to treatment, for an overall response rate of 79%.

Eight patients (8%) achieved a complete response or complete response with incomplete count recovery, 3 (3%) had a near-partial response, and 74 (69%) had a partial response. Twenty-two patients (21%) did not respond.

At the time of analysis, the median duration of response had not been reached. The same was true for progression-free survival and overall survival. The progression-free survival estimate for 12 months was 72%, and the overall survival estimate was 87%.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse was 96%. The most frequent grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (40%), infection (20%), anemia (18%), and thrombocytopenia (15%).

The incidence of serious adverse events was 55%. The most common of these events were pyrexia (7%), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (7%), pneumonia (6%), and febrile neutropenia (5%).

Grade 3 laboratory tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) was reported in 5 patients during the ramp-up period only. Three of these patients continued on venetoclax, but 2 patients required a dose interruption of 1 day each.

In the past, TLS has caused deaths in patients receiving venetoclax. In response, AbbVie stopped dose-escalation in patients receiving the drug and suspended enrollment in phase 1 trials.

However, researchers subsequently found that a modified dosing schedule, prophylaxis, and patient monitoring can reduce the risk of TLS. ![]()

Doc offers advice on choosing a frontline TKI

Photo by D. Meyer

NEW YORK—Evaluating treatment goals is essential when choosing which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) to prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“Deciding what TKI to start people on really depends on what your goals are for that patient,” said the speaker, Jerald Radich, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

Because the 3 TKIs approved for frontline treatment of CML—imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib—produce “amazingly similar” responses, treatment compliance becomes an important factor in patient outcomes, he noted.

“If you take 90% of your imatinib, your MMR [major molecular response] is 90%,” he said. “Your CMR [complete molecular response] is 40%. So taking drug obviously trumps the decision of what drug to take.”

Dr Radich added that the major goal of treatment is to keep patients out of accelerated-phase blast crisis. Once people progress to blast crisis on a TKI, the median survival is less than 1 year.

“So that’s why you treat people aggressively, that’s why you monitor them molecularly, to prevent that from happening,” he said.

Treatment goals

Aside from preventing patients from progressing to blast crisis, treatment goals vary.

Achieving early molecular response (MR) impacts progression and survival, as does achieving a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR).

A major molecular response (MMR) is considered a “safe haven,” Dr Radich said, because once people achieve it, they almost never progress if they stay on drug.

And with a deep/complete molecular response (CMR), patients may potentially discontinue the drug.

So how your response goals line up determines how you use the agents for your treatment course, Dr Radich said.

In all response categories—patients with CCyR, MMR, MR, CMR—survival is virtually within 95% of survival for the general population.

“This is absolutely astonishing,” Dr Radich said.

He emphasized the importance of molecular testing at 3 months and achieving a BCR-ABL level of less than 10%.

Patients who have more than 10% blasts at 3 months have an 88% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years, while those who still have more than 10% blasts at 6 months have a 3.3% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years.

Toxicity

Side effects common to the 3 frontline TKIs are myelosuppression, transaminase elevation, and change in electrolytes. Dr Radich noted that imatinib doesn’t cause much myelosuppression.

“You can give imatinib on day 28 after allogeneic transplant, and it doesn’t affect the counts, which I think is pretty darn good proof that it doesn’t have any primary hematopoietic toxicity,” he said. “You can’t try that trick with the others.”

Venous and arterial cardiovascular events with TKIs are more recently coming to light.

Cardiovascular events with imatinib are about the same as the general population, Dr Radich said.

“[In] fact, some people think it might be protective,” he noted.

Discontinuation

“When we first started treating people with these drugs, we figured that they would be on them for life . . . ,” Dr Radich said. “[Y]ou’d always have a reservoir of CML cells because you can’t extinguish all the stem cells.”

A mathematical model predicted it would take 30 to 40 years to wipe out all CML cells with a TKI. The cumulative cure rate after 15 years of treatment would be 14%. After 30 years, it would be 31%.

Conducting a discontinuation trial would have been out of the question based on these predictions.

“Fortunately, some of the people who did the next trials hadn’t read that literature,” Dr Radich said.

One discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI) included patients who had been on drug for at least 3 years and had CMR for at least 1 year. About half stayed in PCR negativity, now up to 4 years.

A number of trials are now underway evaluating the possibility of TKI discontinuation, and they are showing that between 40% and 50% of patients can remain off drug for years.

Using generic imatinib

While generic imatinib is good for cost-effective, long-term use, second-generation TKIs are better at preventing accelerated-phase blast crisis, Dr Radich said.

The second generation is also better at producing deep remissions, and discontinuation could bring with it a cost savings.

Dr Radich calculated that it cost about $2.5 million for every patient who achieves treatment-free remission using a TKI, while transplant cost $1.31 million per patient who achieves treatment-free remission.

So generic imatinib is good for low- and intermediate-risk patients, as well as for older, sicker patients.

Second-generation TKIs are appropriate for higher-risk patients until they achieve a CCyR or MMR, then they can switch to generic imatinib.

And second-generation TKIs should be used for younger patients in whom drug discontinuation is important.

Frontline treatment observations

In summary, Dr Radich made the following observations about frontline treatment in CML.

- For overall survival, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- To achieve a deep MR, a second-generation TKI is better than imatinib.

- Discontinuation is equally successful with all TKIs.

- For lower-risk CML, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- When it comes to progression and possibly high-risk CML, second-generation TKIs are better than imatinib.

- Second-generation TKIs produce more long-term toxicities than imatinib.

- There is substantial cost savings with generics.

Photo by D. Meyer

NEW YORK—Evaluating treatment goals is essential when choosing which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) to prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“Deciding what TKI to start people on really depends on what your goals are for that patient,” said the speaker, Jerald Radich, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

Because the 3 TKIs approved for frontline treatment of CML—imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib—produce “amazingly similar” responses, treatment compliance becomes an important factor in patient outcomes, he noted.

“If you take 90% of your imatinib, your MMR [major molecular response] is 90%,” he said. “Your CMR [complete molecular response] is 40%. So taking drug obviously trumps the decision of what drug to take.”

Dr Radich added that the major goal of treatment is to keep patients out of accelerated-phase blast crisis. Once people progress to blast crisis on a TKI, the median survival is less than 1 year.

“So that’s why you treat people aggressively, that’s why you monitor them molecularly, to prevent that from happening,” he said.

Treatment goals

Aside from preventing patients from progressing to blast crisis, treatment goals vary.

Achieving early molecular response (MR) impacts progression and survival, as does achieving a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR).

A major molecular response (MMR) is considered a “safe haven,” Dr Radich said, because once people achieve it, they almost never progress if they stay on drug.

And with a deep/complete molecular response (CMR), patients may potentially discontinue the drug.

So how your response goals line up determines how you use the agents for your treatment course, Dr Radich said.

In all response categories—patients with CCyR, MMR, MR, CMR—survival is virtually within 95% of survival for the general population.

“This is absolutely astonishing,” Dr Radich said.

He emphasized the importance of molecular testing at 3 months and achieving a BCR-ABL level of less than 10%.

Patients who have more than 10% blasts at 3 months have an 88% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years, while those who still have more than 10% blasts at 6 months have a 3.3% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years.

Toxicity

Side effects common to the 3 frontline TKIs are myelosuppression, transaminase elevation, and change in electrolytes. Dr Radich noted that imatinib doesn’t cause much myelosuppression.

“You can give imatinib on day 28 after allogeneic transplant, and it doesn’t affect the counts, which I think is pretty darn good proof that it doesn’t have any primary hematopoietic toxicity,” he said. “You can’t try that trick with the others.”

Venous and arterial cardiovascular events with TKIs are more recently coming to light.

Cardiovascular events with imatinib are about the same as the general population, Dr Radich said.

“[In] fact, some people think it might be protective,” he noted.

Discontinuation

“When we first started treating people with these drugs, we figured that they would be on them for life . . . ,” Dr Radich said. “[Y]ou’d always have a reservoir of CML cells because you can’t extinguish all the stem cells.”

A mathematical model predicted it would take 30 to 40 years to wipe out all CML cells with a TKI. The cumulative cure rate after 15 years of treatment would be 14%. After 30 years, it would be 31%.

Conducting a discontinuation trial would have been out of the question based on these predictions.

“Fortunately, some of the people who did the next trials hadn’t read that literature,” Dr Radich said.

One discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI) included patients who had been on drug for at least 3 years and had CMR for at least 1 year. About half stayed in PCR negativity, now up to 4 years.

A number of trials are now underway evaluating the possibility of TKI discontinuation, and they are showing that between 40% and 50% of patients can remain off drug for years.

Using generic imatinib

While generic imatinib is good for cost-effective, long-term use, second-generation TKIs are better at preventing accelerated-phase blast crisis, Dr Radich said.

The second generation is also better at producing deep remissions, and discontinuation could bring with it a cost savings.

Dr Radich calculated that it cost about $2.5 million for every patient who achieves treatment-free remission using a TKI, while transplant cost $1.31 million per patient who achieves treatment-free remission.

So generic imatinib is good for low- and intermediate-risk patients, as well as for older, sicker patients.

Second-generation TKIs are appropriate for higher-risk patients until they achieve a CCyR or MMR, then they can switch to generic imatinib.

And second-generation TKIs should be used for younger patients in whom drug discontinuation is important.

Frontline treatment observations

In summary, Dr Radich made the following observations about frontline treatment in CML.

- For overall survival, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- To achieve a deep MR, a second-generation TKI is better than imatinib.

- Discontinuation is equally successful with all TKIs.

- For lower-risk CML, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- When it comes to progression and possibly high-risk CML, second-generation TKIs are better than imatinib.

- Second-generation TKIs produce more long-term toxicities than imatinib.

- There is substantial cost savings with generics.

Photo by D. Meyer

NEW YORK—Evaluating treatment goals is essential when choosing which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) to prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to a speaker at the NCCN 11th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“Deciding what TKI to start people on really depends on what your goals are for that patient,” said the speaker, Jerald Radich, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

Because the 3 TKIs approved for frontline treatment of CML—imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib—produce “amazingly similar” responses, treatment compliance becomes an important factor in patient outcomes, he noted.

“If you take 90% of your imatinib, your MMR [major molecular response] is 90%,” he said. “Your CMR [complete molecular response] is 40%. So taking drug obviously trumps the decision of what drug to take.”

Dr Radich added that the major goal of treatment is to keep patients out of accelerated-phase blast crisis. Once people progress to blast crisis on a TKI, the median survival is less than 1 year.

“So that’s why you treat people aggressively, that’s why you monitor them molecularly, to prevent that from happening,” he said.

Treatment goals

Aside from preventing patients from progressing to blast crisis, treatment goals vary.

Achieving early molecular response (MR) impacts progression and survival, as does achieving a complete cytogenetic response (CCyR).

A major molecular response (MMR) is considered a “safe haven,” Dr Radich said, because once people achieve it, they almost never progress if they stay on drug.

And with a deep/complete molecular response (CMR), patients may potentially discontinue the drug.

So how your response goals line up determines how you use the agents for your treatment course, Dr Radich said.

In all response categories—patients with CCyR, MMR, MR, CMR—survival is virtually within 95% of survival for the general population.

“This is absolutely astonishing,” Dr Radich said.

He emphasized the importance of molecular testing at 3 months and achieving a BCR-ABL level of less than 10%.

Patients who have more than 10% blasts at 3 months have an 88% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years, while those who still have more than 10% blasts at 6 months have a 3.3% chance of achieving MMR at 4 years.

Toxicity

Side effects common to the 3 frontline TKIs are myelosuppression, transaminase elevation, and change in electrolytes. Dr Radich noted that imatinib doesn’t cause much myelosuppression.

“You can give imatinib on day 28 after allogeneic transplant, and it doesn’t affect the counts, which I think is pretty darn good proof that it doesn’t have any primary hematopoietic toxicity,” he said. “You can’t try that trick with the others.”

Venous and arterial cardiovascular events with TKIs are more recently coming to light.

Cardiovascular events with imatinib are about the same as the general population, Dr Radich said.

“[In] fact, some people think it might be protective,” he noted.

Discontinuation

“When we first started treating people with these drugs, we figured that they would be on them for life . . . ,” Dr Radich said. “[Y]ou’d always have a reservoir of CML cells because you can’t extinguish all the stem cells.”

A mathematical model predicted it would take 30 to 40 years to wipe out all CML cells with a TKI. The cumulative cure rate after 15 years of treatment would be 14%. After 30 years, it would be 31%.

Conducting a discontinuation trial would have been out of the question based on these predictions.

“Fortunately, some of the people who did the next trials hadn’t read that literature,” Dr Radich said.

One discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI) included patients who had been on drug for at least 3 years and had CMR for at least 1 year. About half stayed in PCR negativity, now up to 4 years.

A number of trials are now underway evaluating the possibility of TKI discontinuation, and they are showing that between 40% and 50% of patients can remain off drug for years.

Using generic imatinib

While generic imatinib is good for cost-effective, long-term use, second-generation TKIs are better at preventing accelerated-phase blast crisis, Dr Radich said.

The second generation is also better at producing deep remissions, and discontinuation could bring with it a cost savings.

Dr Radich calculated that it cost about $2.5 million for every patient who achieves treatment-free remission using a TKI, while transplant cost $1.31 million per patient who achieves treatment-free remission.

So generic imatinib is good for low- and intermediate-risk patients, as well as for older, sicker patients.

Second-generation TKIs are appropriate for higher-risk patients until they achieve a CCyR or MMR, then they can switch to generic imatinib.

And second-generation TKIs should be used for younger patients in whom drug discontinuation is important.

Frontline treatment observations

In summary, Dr Radich made the following observations about frontline treatment in CML.

- For overall survival, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- To achieve a deep MR, a second-generation TKI is better than imatinib.

- Discontinuation is equally successful with all TKIs.

- For lower-risk CML, imatinib is equivalent to second-generation TKIs.

- When it comes to progression and possibly high-risk CML, second-generation TKIs are better than imatinib.

- Second-generation TKIs produce more long-term toxicities than imatinib.

- There is substantial cost savings with generics.

Findings may aid drug delivery, bioimaging

to illuminate microfluidic device

simulating a blood vessel.

Photo from Anson Ma/UConn

A study published in Biophysical Journal has revealed new information about how particles behave in the bloodstream, and investigators believe the findings have implications for bioimaging and targeted drug delivery in cancer.

The investigators used a microfluidic channel device to observe, track, and measure how individual particles behave in a simulated blood vessel.

Their goal was to learn more about the physics influencing a particle’s behavior as it travels in the blood and to determine which particle size might be the most effective for delivering drugs to their targets.

“Even before particles reach a target site, you have to worry about what is going to happen with them after they get injected into the bloodstream,” said study author Anson Ma, PhD, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut.

“Are they going to clump together? How are they going to move around? Are they going to get swept away and flushed out of our bodies?”

Using a high-powered fluorescence microscope, Dr Ma and his colleagues were able to observe particles being carried along in the simulated blood vessel in what could be described as a vascular “Running of the Bulls.”

Red blood cells raced through the middle of the channel, and the particles were carried along in the rush, bumping and bouncing off the blood cells until they were pushed to open spaces—called the cell-free layer—along the vessel’s walls.

The investigators found that larger particles—the optimum size appeared to be about 2 microns—were most likely to get pushed to the cell-free layer, where their chances of carrying a drug to a targeted site are greatest.

The team also determined that 2 microns was the largest size that should be used if particles are going to have any chance of going through the leaky blood vessel walls to the site.

“When it comes to using particles for the delivery of cancer drugs, size matters,” Dr Ma said. “When you have a bigger particle, the chance of it bumping into blood cells is much higher, there are a lot more collisions, and they tend to get pushed to the blood vessel walls.”

These results were somewhat surprising. The investigators had theorized that smaller particles would probably be the most effective since they would move the most in collisions with blood cells.

But the opposite proved true. The smaller particles appeared to skirt through the mass of moving blood cells and were less likely to get bounced to the cell-free layer.

Knowing how particles behave in the circulatory system should help improve targeted drug delivery, Dr Ma said. And this should further reduce the side effects caused by potent cancer drugs missing their target.

Measuring how different sized particles move in the bloodstream may also be beneficial in bioimaging, where the goal is to keep particles circulating in the bloodstream long enough for imaging to occur. In that case, smaller particles would be better, Dr Ma said.

Moving forward, Dr Ma would like to explore other aspects of particle flow in the circulatory system, such as how particles behave when they pass through a constricted area, like from a blood vessel to a capillary.

Capillaries are only about 7 microns in diameter. Dr Ma said he would like to know how that constricted space might impact particle flow or the ability of particles to accumulate near the vessel walls.

“We have all of this complex geometry in our bodies,” Dr Ma said. “Most people just assume there is no impact when a particle moves from a bigger channel to a smaller channel because they haven’t quantified it. Our plan is to do some experiments to look at this more carefully, building on the work that we just published.” ![]()

to illuminate microfluidic device

simulating a blood vessel.

Photo from Anson Ma/UConn

A study published in Biophysical Journal has revealed new information about how particles behave in the bloodstream, and investigators believe the findings have implications for bioimaging and targeted drug delivery in cancer.

The investigators used a microfluidic channel device to observe, track, and measure how individual particles behave in a simulated blood vessel.

Their goal was to learn more about the physics influencing a particle’s behavior as it travels in the blood and to determine which particle size might be the most effective for delivering drugs to their targets.

“Even before particles reach a target site, you have to worry about what is going to happen with them after they get injected into the bloodstream,” said study author Anson Ma, PhD, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut.

“Are they going to clump together? How are they going to move around? Are they going to get swept away and flushed out of our bodies?”

Using a high-powered fluorescence microscope, Dr Ma and his colleagues were able to observe particles being carried along in the simulated blood vessel in what could be described as a vascular “Running of the Bulls.”

Red blood cells raced through the middle of the channel, and the particles were carried along in the rush, bumping and bouncing off the blood cells until they were pushed to open spaces—called the cell-free layer—along the vessel’s walls.

The investigators found that larger particles—the optimum size appeared to be about 2 microns—were most likely to get pushed to the cell-free layer, where their chances of carrying a drug to a targeted site are greatest.

The team also determined that 2 microns was the largest size that should be used if particles are going to have any chance of going through the leaky blood vessel walls to the site.

“When it comes to using particles for the delivery of cancer drugs, size matters,” Dr Ma said. “When you have a bigger particle, the chance of it bumping into blood cells is much higher, there are a lot more collisions, and they tend to get pushed to the blood vessel walls.”

These results were somewhat surprising. The investigators had theorized that smaller particles would probably be the most effective since they would move the most in collisions with blood cells.

But the opposite proved true. The smaller particles appeared to skirt through the mass of moving blood cells and were less likely to get bounced to the cell-free layer.

Knowing how particles behave in the circulatory system should help improve targeted drug delivery, Dr Ma said. And this should further reduce the side effects caused by potent cancer drugs missing their target.

Measuring how different sized particles move in the bloodstream may also be beneficial in bioimaging, where the goal is to keep particles circulating in the bloodstream long enough for imaging to occur. In that case, smaller particles would be better, Dr Ma said.

Moving forward, Dr Ma would like to explore other aspects of particle flow in the circulatory system, such as how particles behave when they pass through a constricted area, like from a blood vessel to a capillary.

Capillaries are only about 7 microns in diameter. Dr Ma said he would like to know how that constricted space might impact particle flow or the ability of particles to accumulate near the vessel walls.

“We have all of this complex geometry in our bodies,” Dr Ma said. “Most people just assume there is no impact when a particle moves from a bigger channel to a smaller channel because they haven’t quantified it. Our plan is to do some experiments to look at this more carefully, building on the work that we just published.” ![]()

to illuminate microfluidic device

simulating a blood vessel.

Photo from Anson Ma/UConn

A study published in Biophysical Journal has revealed new information about how particles behave in the bloodstream, and investigators believe the findings have implications for bioimaging and targeted drug delivery in cancer.

The investigators used a microfluidic channel device to observe, track, and measure how individual particles behave in a simulated blood vessel.

Their goal was to learn more about the physics influencing a particle’s behavior as it travels in the blood and to determine which particle size might be the most effective for delivering drugs to their targets.

“Even before particles reach a target site, you have to worry about what is going to happen with them after they get injected into the bloodstream,” said study author Anson Ma, PhD, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, Connecticut.

“Are they going to clump together? How are they going to move around? Are they going to get swept away and flushed out of our bodies?”

Using a high-powered fluorescence microscope, Dr Ma and his colleagues were able to observe particles being carried along in the simulated blood vessel in what could be described as a vascular “Running of the Bulls.”

Red blood cells raced through the middle of the channel, and the particles were carried along in the rush, bumping and bouncing off the blood cells until they were pushed to open spaces—called the cell-free layer—along the vessel’s walls.

The investigators found that larger particles—the optimum size appeared to be about 2 microns—were most likely to get pushed to the cell-free layer, where their chances of carrying a drug to a targeted site are greatest.

The team also determined that 2 microns was the largest size that should be used if particles are going to have any chance of going through the leaky blood vessel walls to the site.

“When it comes to using particles for the delivery of cancer drugs, size matters,” Dr Ma said. “When you have a bigger particle, the chance of it bumping into blood cells is much higher, there are a lot more collisions, and they tend to get pushed to the blood vessel walls.”

These results were somewhat surprising. The investigators had theorized that smaller particles would probably be the most effective since they would move the most in collisions with blood cells.

But the opposite proved true. The smaller particles appeared to skirt through the mass of moving blood cells and were less likely to get bounced to the cell-free layer.

Knowing how particles behave in the circulatory system should help improve targeted drug delivery, Dr Ma said. And this should further reduce the side effects caused by potent cancer drugs missing their target.

Measuring how different sized particles move in the bloodstream may also be beneficial in bioimaging, where the goal is to keep particles circulating in the bloodstream long enough for imaging to occur. In that case, smaller particles would be better, Dr Ma said.

Moving forward, Dr Ma would like to explore other aspects of particle flow in the circulatory system, such as how particles behave when they pass through a constricted area, like from a blood vessel to a capillary.

Capillaries are only about 7 microns in diameter. Dr Ma said he would like to know how that constricted space might impact particle flow or the ability of particles to accumulate near the vessel walls.

“We have all of this complex geometry in our bodies,” Dr Ma said. “Most people just assume there is no impact when a particle moves from a bigger channel to a smaller channel because they haven’t quantified it. Our plan is to do some experiments to look at this more carefully, building on the work that we just published.” ![]()

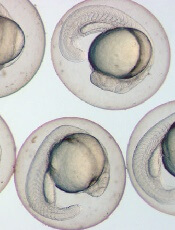

Vitamin D affects HSPC production, team says

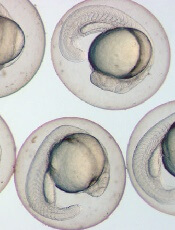

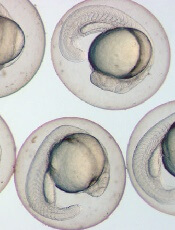

Photo by Ian Johnston

The availability of vitamin D during embryonic development can affect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), according to research published in Cell Reports.

Experiments with zebrafish embryos suggested that vitamin D acts directly on HSPCs to increase proliferation.

Similarly, in HSPCs from human umbilical cords, treatment with vitamin D enhanced hematopoietic colony numbers.

Researchers therefore theorized that vitamin D supplementation might be useful for HSPC expansion prior to transplant.

“We clearly showed that not getting enough vitamin D can alter how blood stem cells are formed,” said study author Trista North, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Vitamin D was having a direct response on the blood stem cells, and it changed what those cells did in terms of multiplying and staying alive.”

The researchers found, in both human and zebrafish tissue, that 1,25(OH)D3 (active vitamin D3) had an impact on HSPC production and function.

Investigation into the mechanism revealed that CXCL8-CXCR1/2 signaling functions downstream of 1,25(OH)D3-mediated vitamin D receptor stimulation to directly regulate HSPC production and expansion.

“What was surprising was that vitamin D is having an impact so early,” Dr North said. “We really only thought about vitamin D in terms of bone development and maintenance, but we clearly show that, whether they were zebrafish or human blood stem cells, they can respond directly to the nutrient.”

One caveat is the researchers did face difficulty testing the response in mice, as the animals don’t have the same vitamin D inflammatory targets observed in zebrafish and humans.

Additionally, the team didn’t know the vitamin D levels in the umbilical cord blood samples they tested, which may have influenced the outcome of their analysis.

As a next step, Dr North and her colleagues hope to test cord blood samples for which they know the vitamin D status to see if umbilical cords with healthy levels respond better or worse to stimulation than cords from vitamin-D-deficient donors. ![]()

Photo by Ian Johnston

The availability of vitamin D during embryonic development can affect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), according to research published in Cell Reports.

Experiments with zebrafish embryos suggested that vitamin D acts directly on HSPCs to increase proliferation.

Similarly, in HSPCs from human umbilical cords, treatment with vitamin D enhanced hematopoietic colony numbers.

Researchers therefore theorized that vitamin D supplementation might be useful for HSPC expansion prior to transplant.

“We clearly showed that not getting enough vitamin D can alter how blood stem cells are formed,” said study author Trista North, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Vitamin D was having a direct response on the blood stem cells, and it changed what those cells did in terms of multiplying and staying alive.”

The researchers found, in both human and zebrafish tissue, that 1,25(OH)D3 (active vitamin D3) had an impact on HSPC production and function.

Investigation into the mechanism revealed that CXCL8-CXCR1/2 signaling functions downstream of 1,25(OH)D3-mediated vitamin D receptor stimulation to directly regulate HSPC production and expansion.

“What was surprising was that vitamin D is having an impact so early,” Dr North said. “We really only thought about vitamin D in terms of bone development and maintenance, but we clearly show that, whether they were zebrafish or human blood stem cells, they can respond directly to the nutrient.”

One caveat is the researchers did face difficulty testing the response in mice, as the animals don’t have the same vitamin D inflammatory targets observed in zebrafish and humans.

Additionally, the team didn’t know the vitamin D levels in the umbilical cord blood samples they tested, which may have influenced the outcome of their analysis.

As a next step, Dr North and her colleagues hope to test cord blood samples for which they know the vitamin D status to see if umbilical cords with healthy levels respond better or worse to stimulation than cords from vitamin-D-deficient donors. ![]()

Photo by Ian Johnston

The availability of vitamin D during embryonic development can affect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), according to research published in Cell Reports.

Experiments with zebrafish embryos suggested that vitamin D acts directly on HSPCs to increase proliferation.

Similarly, in HSPCs from human umbilical cords, treatment with vitamin D enhanced hematopoietic colony numbers.

Researchers therefore theorized that vitamin D supplementation might be useful for HSPC expansion prior to transplant.

“We clearly showed that not getting enough vitamin D can alter how blood stem cells are formed,” said study author Trista North, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Vitamin D was having a direct response on the blood stem cells, and it changed what those cells did in terms of multiplying and staying alive.”

The researchers found, in both human and zebrafish tissue, that 1,25(OH)D3 (active vitamin D3) had an impact on HSPC production and function.

Investigation into the mechanism revealed that CXCL8-CXCR1/2 signaling functions downstream of 1,25(OH)D3-mediated vitamin D receptor stimulation to directly regulate HSPC production and expansion.

“What was surprising was that vitamin D is having an impact so early,” Dr North said. “We really only thought about vitamin D in terms of bone development and maintenance, but we clearly show that, whether they were zebrafish or human blood stem cells, they can respond directly to the nutrient.”

One caveat is the researchers did face difficulty testing the response in mice, as the animals don’t have the same vitamin D inflammatory targets observed in zebrafish and humans.

Additionally, the team didn’t know the vitamin D levels in the umbilical cord blood samples they tested, which may have influenced the outcome of their analysis.

As a next step, Dr North and her colleagues hope to test cord blood samples for which they know the vitamin D status to see if umbilical cords with healthy levels respond better or worse to stimulation than cords from vitamin-D-deficient donors. ![]()

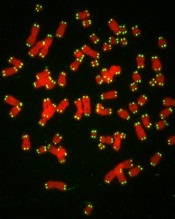

Lifestyle may impact life expectancy in mild SCD

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

alongside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

A case series published in Blood indicates that some patients with mildly symptomatic sickle cell disease (SCD) can live long lives if they

comply with treatment recommendations and lead a healthy lifestyle.

The paper includes details on 4 women with milder forms of SCD who survived beyond age 80.

“For those with mild forms of SCD, these women show that lifestyle modifications may improve disease outcomes,” said author Samir K. Ballas, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Three of the women described in this case series were treated at the Sickle Cell Center of Thomas Jefferson University, and 1 was treated in Brazil’s Instituto de Hematologia Arthur de Siqueira Cavalcanti in Rio de Janeiro.

The women had different ancestries—2 African-American, 1 Italian-American, and 1 African-Brazilian—and different diagnoses—2 with hemoglobin SC disease and 2 with sickle cell anemia. But all 4 women had what Dr Ballas called “desirable” disease states.

“These women never had a stroke, never had recurrent acute chest syndrome, had a relatively high fetal hemoglobin count, and had infrequent painful crises,” Dr Ballas said. “Patients like this usually—but not always—experience relatively mild SCD, and they live longer with better quality of life.”

In addition, all of the women took steps to maintain and improve their health and had long-term family support. Dr Ballas said these factors likely contributed to the women’s long lives and high quality of life.

“All of the women were non-smokers who consumed little to no alcohol and maintained a normal body mass index,” he said. “This was coupled with a strong compliance to their treatment regimens and excellent family support at home.”

Family support was defined as having a spouse or child who provided attentive, ongoing care. And all of the women had at least 1 such caregiver.

Treatment compliance was based on observations by healthcare providers, including study authors. According to these observations, all of the women showed “excellent” adherence when it came to medication intake, appointments, and referrals.

As the women had relatively mild disease states, none of them were qualified to receive treatment with hydroxyurea. Instead, they received hydration, vaccination (including annual flu shots), and blood transfusion and analgesics as needed.

Even with their mild disease states and healthy lifestyles, these women did not live crisis-free lives. Each experienced disease-related complications necessitating medical attention.

The women had 0 to 3 vaso-occlusive crises per year. Two women required frequent transfusions (and had iron overload), and 2 required occasional transfusions. One woman had 2 episodes of acute chest syndrome, and the second episode led to her death.

Ultimately, 3 of the women died. One died of acute chest syndrome and septicemia at age 82, and another died of cardiac complications at age 86. For a third woman, the cause of death, at age 82, was unknown. The fourth woman remains alive at age 82.

As the median life expectancy of women with SCD in the US is 47, Dr Ballas and his colleagues said these 4 women may “provide a blueprint of how to live a long life despite having a serious medical condition like SCD.”

“I would often come out to the waiting room and find these ladies talking with other SCD patients, and I could tell that they gave others hope, that just because they have SCD does not mean that they are doomed to die by their 40s . . . ,” Dr Ballas said. “[I]f they take care of themselves and live closely with those who can help keep them well, that there is hope for them to lead long, full lives.” ![]()

Factor IX therapy approved in Australia

The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved albutrepenonacog alfa (Idelvion) to treat hemophilia B patients of all ages.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin.

The product is now approved in Australia for use as routine prophylaxis to prevent and reduce the frequency of bleeding, for on-demand control of bleeding, and for perioperative management of

bleeding.

Albutrepenonacog alfa has also been approved in Canada, the European Union, Japan, Switzerland, and the US.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring.

The company says albutrepenonacog alfa is the first and only Australian-registered factor IX therapy that delivers high-level protection from bleeding with up to 14-day dosing for appropriate patients.

According to CSL Behring, albutrepenonacog alfa can deliver high-level protection by maintaining factor IX activity levels at an average of 20% in patients treated prophylactically every 7 days and an average of 12% in patients treated prophylactically every 14 days.

“The Australian Haemophilia Centre Directors’ Organisation (AHCDO) views the development of effective long-acting clotting factor concentrates as a major step forward in the management of our patients with hemophilia,” said Simon McRae, MMBS, consultant hematologist and chairman of AHCDO.

“The ability to maintain clotting factor levels above a level that prevent the vast majority of bleeding events with less frequent infusions has the potential to improve long-term outcomes in individuals with hemophilia.”

Phase 3 trial

The Therapeutic Goods Administration approved albutrepenonacog alfa based on results of the PROLONG-9FP clinical development program. PROLONG-9FP includes phase 1, 2, and 3 studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of albutrepenonacog alfa in adults and children (ages 1 to 61) with hemophilia B.

Data from the phase 3 study were published in Blood. The study included 63 previously treated male patients with severe hemophilia B. They had a mean age of 33 (range, 12 to 61).

The patients were divided into 2 groups. Group 1 (n=40) received routine prophylaxis with albutrepenonacog alfa once every 7 days for 26 weeks, followed by a 7-, 10-, or 14-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 50, 38, or 51 weeks, respectively.

Group 2 received on-demand treatment with albutrepenonacog alfa for bleeding episodes for 26 weeks (n=23) and then switched to a 7-day prophylaxis regimen for a mean of 45 weeks (n=19).

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was 2.0 in the prophylaxis arm (group 1) and 23.5 in the on-demand treatment arm (group 2). The median spontaneous ABRs were 0.0 and 17.0, respectively.

For patients in group 2, there was a significant reduction in median ABRs when patients switched from on-demand treatment to prophylaxis—19.22 and 1.58, respectively (P<0.0001). And there was a significant reduction in median spontaneous ABRs—15.43 and 0.00, respectively (P<0.0001).

Overall, 98.6% of bleeding episodes were treated successfully, including 93.6% that were treated with a single injection of albutrepenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed inhibitors or experienced thromboembolic events, anaphylaxis, or life-threatening adverse events (AEs).

There were 347 treatment-emergent AEs reported in 54 (85.7%) patients. The most common were nasopharyngitis (25.4%), headache (23.8%), arthralgia (4.3%), and influenza (11.1%).

Eleven mild/moderate AEs in 5 patients (7.9%) were considered possibly related to albutrepenonacog alfa. Two patients discontinued treatment due to AEs—1 with hypersensitivity and 1 with headache.

“I have seen first-hand the benefits Idelvion has had on children with hemophilia B,” said PROLONG-9FP investigator Julie Curtin, MBBS, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital at Westmead in New South Wales.

“Idelvion has enabled children on regular treatment with factor IX to reduce the frequency of infusions without increasing their risk of bleeding. For a child to only need an injection every 1-2 weeks is a good step forward in the management of hemophilia B, which I welcome, and I am sure my patients will welcome this improvement too.” ![]()

The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved albutrepenonacog alfa (Idelvion) to treat hemophilia B patients of all ages.

Albutrepenonacog alfa is a fusion protein linking recombinant coagulation factor IX with recombinant albumin.