User login

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

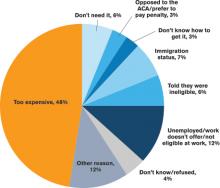

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

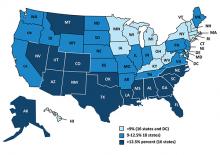

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.