User login

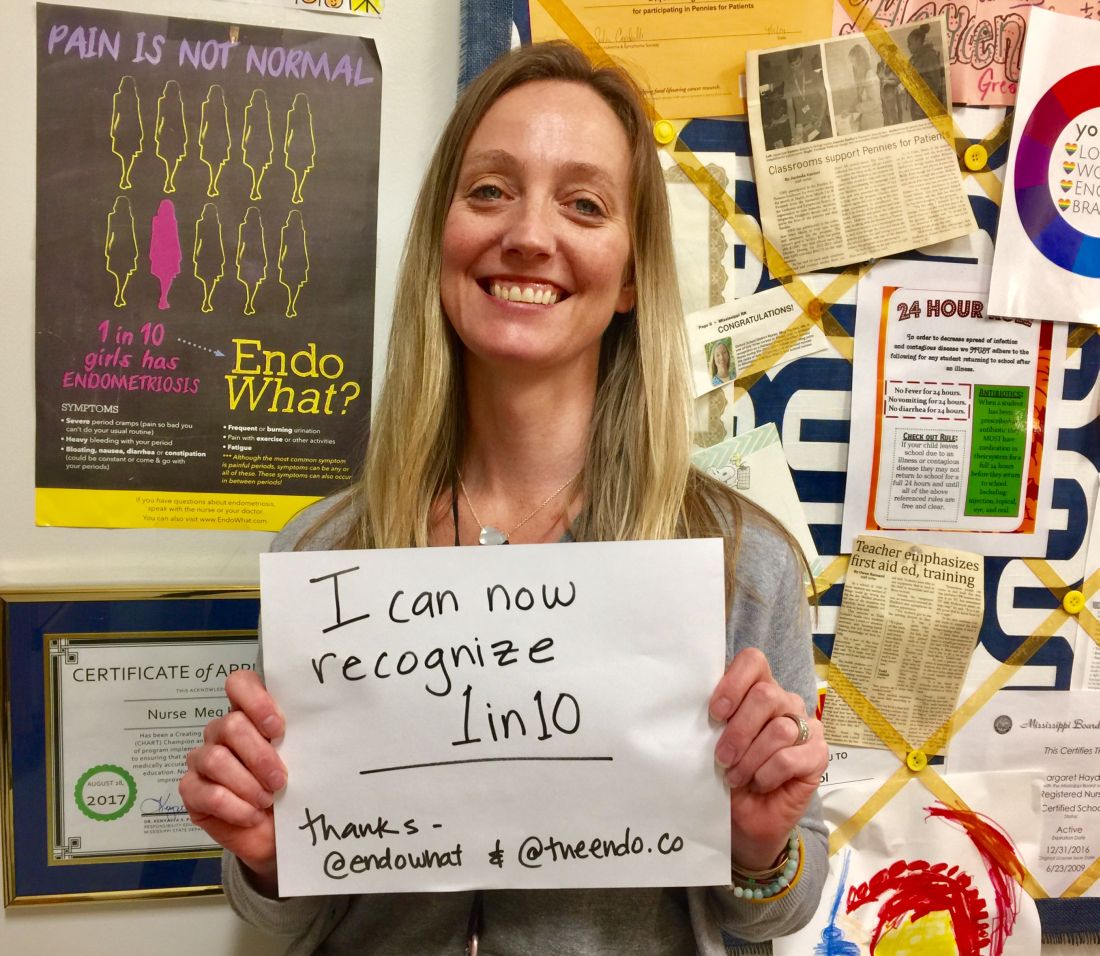

Meg Hayden, RN, a school nurse in Oxford, Miss., used to be a labor and delivery nurse and considers herself more attuned to women’s health issues than other school nurses are. Still, a new educational initiative on endometriosis that stresses that menstrual pain is not normal – and that teenagers are not too young to have endometriosis – has helped her “connect the dots.”

“It’s a good reminder for me to look at patterns” and advise those girls who have repeated episodes of pelvic pain and other symptoms to “keep a diary” and to seek care, Ms. Hayden said.

They are demanding that serious diagnostic delays be rectified – that disease symptoms be better recognized by gynecologists, pediatricians, and other primary care physicians – and then, that the disease be better managed.

Some of the advocacy groups have petitioned the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to involve patients and endometriosis experts in creating new standards of care. And at press time, activist Shannon Cohn, who developed the School Nurse initiative after producing a documentary film titled Endo What?, was working with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) on finalizing plans for a national public service announcement campaign. (Sen. Hatch wrote an opinion piece for CNN in late March describing his granddaughter’s experience with the disease and calling the widespread prevalence of the disease – and the lack of any long-term treatment options – “nothing short of a public health emergency.”)

Estimates vary, but the average interval between presentation of symptoms and definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy (and usually) biopsy is commonly reported as 7-10 years. The disease can cause incapacitating pain, missed days of school and work, and increasing morbidities over time, including infertility and organ damage both inside and outside the pelvic cavity. A majority of women with endometriosis – two-thirds, according to one survey of more than 4,300 women with surgically diagnosed disease (Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9) – report first experiencing symptoms during adolescence.

Yet, too often, adolescents believe or are told that “periods are supposed to hurt,” and other symptoms of the disease – such as gastrointestinal symptoms – are overlooked.

“If we can diagnose endometriosis in its early stages, we could prevent a lifetime of pain and suffering, and decrease rates of infertility ... hopefully stopping disease progression before it does damage,” said Marc R. Laufer, MD, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. “If we don’t, we’re missing a huge opportunity because we know that endometriosis affects 10% of women.”

Atypical symptoms and presentation

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. It traditionally has been associated with retrograde menstruation, but today, there are more nuanced and likely overlapping theories of etiology. Identified in girls even prior to the onset of menses, the disease is generally believed to be progressive, but perhaps not all the time. Patients with significant amounts of disease may have tremendous pain or they may have very little discomfort.

While adolescents can have advanced endometriosis, most have early-stage disease, experts say. Still, adolescence offers its own complexities. Preteen and teen patients with endometriosis tend to present more often with atypical symptoms and with much more subtle and variable laparoscopic findings than do adult patients. Dr. Laufer reported more than 20 years ago that only 9.7% of 46 girls presented classically with dysmenorrhea. In 63%, pain was both acyclic and cyclic, and in 28%, pain was acyclic only (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199-202).

In a more recent report on adolescents treated by gynecologic surgeon Ceana Nezhat, MD, 64% had dysmenorrhea, 44% had menorrhagia, 60% had abnormal or irregular uterine bleeding, 56% had at least one gastrointestinal symptom, and 52% had at least one genitourinary symptom. The girls had seen a mean of three physicians, including psychiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, and had received diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, appendicitis, ovarian cysts, and musculoskeletal pain (JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00019). Notably, 56% had a family history of endometriosis, Dr. Nezhat, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, and his colleagues found.

To address levels of pain, Dr. Laufer usually asks young women if they feel they’re at a disadvantage to other young women or to men. This opens the door to learning more about school absences, missed activities, and decreased quality of life. Pain, he emphasizes, is only part of the picture. “It’s also about fatigue and energy levels, social interaction, depression, sexual function if they’re sexually active, body image issues, and bowel and bladder functionality.”

If the new generation of school nurse programs and other educational initiatives are successful, teens will increasingly come to appointments with notes in hand. Ms. Hayden counsels students on what to discuss with the doctor. And high school students in New York who have been educated through the Endometriosis Foundation of America’s 5-year-old ENPOWR Project for endometriosis education are urged to keep a journal or use a symptom tracker app if they are experiencing pain or other symptoms associated with endometriosis.

“We tell them that, with a record, you can show that the second week of every month I’m in terrible pain, for instance, or I’ve fainted twice in the last month, or here’s when my nausea is really aggressive,” said Nina Baker, outreach coordinator for the foundation. “We’re very honest about how often this is dismissed ... and we assure them that by no means are you wrong about your pain.”

ENPOWR lessons have been taught in more than 165 schools thus far (mostly in health classes in New York schools and largely by foundation-trained educators), and a recently developed online package of educational materials for schools – the Endo EduKit – is expanding the foundation’s geographical reach to other states. Students are encouraged during the training to see a gynecologist if they’re concerned about endometriosis, Ms. Baker said.

In Mississippi, Ms. Hayden suggests that younger high-schoolers see their pediatrician, but after that, “I feel like they should go to the gynecologist.” (ACOG recommends a first visit to the gynecologist between the ages of 13 and 15 for anticipatory guidance.) The year-old School Nurse Initiative has sent toolkits, posters, and DVD copies of the “Endo What?” film to nurses in 652 schools thus far. “Our goal,” said Ms. Cohn, a lawyer, filmmaker, and an endometriosis patient, “is to educate every school nurse in middle and high schools across the country.”

Treatment dilemmas

The first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea and for suspected endometriosis in adolescents has long been empiric treatment with NSAIDs and oral contraceptive pills. Experts commonly recommend today that combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) be started cyclically and then changed to continuous dosing if necessary with the goal of inducing amenorrhea.

If symptoms are not well controlled within 3-6 months of compliant medication management with COCPs and NSAIDs and endometriosis is suspected, then laparoscopy by a physician who is familiar with adolescent endometriosis and can simultaneously diagnose and treat the disease should be considered, according to Dr. Laufer and several other experts in pediatric and adolescent gynecology who spoke with Ob.Gyn. News.

“If someone still has pain on one COCP, then switching to another COCP is not going to solve the problem – there is no study that shows that one pill is better than another,” Dr. Laufer said.

Yet extra months and sometimes years of pill-switching and empiric therapy with other medications – rather than surgical evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment – is not uncommon. “Usually, by the time a patient comes to me, they’ve already been on multiple birth control pills, they’ve failed NSAIDs, and they’ve often tried other medications as well,” such as progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, said Iris Kerin Orbuch, MD, director of the Advanced Gynecologic Laparoscopy Centers in New York and Los Angeles.

Some also have had diagnostic laparoscopies and been wrongly told that nothing is wrong. Endometriosis is “not all powder-burn lesions and chocolate cysts, which is what we’re taught in medical school,” she said. “It can have many appearances, especially in teens and adolescents. It can be clear vesicles, white, fibrotic, yellow, blue, and brown ... and quite commonly there can simply be areas of increased vascularity. I only learned this in my fellowship.”

Dr. Orbuch, who routinely treats adolescents with endometriosis, takes a holistic approach to the disease that includes working with patients – often before surgery and in partnership with other providers – to downregulate the central nervous system and to alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction that often develops secondary to the disease. When she does operate and finds endometriosis, she performs excisional surgery, in contrast with ablative techniques such as cauterization or desiccation that are used by many physicians.

Treatment of endometriosis is rife with dilemmas, controversies, and shortcomings. Medical treatments can improve pain, but as ACOG’s current Practice Bulletin (No. 114) points out, recurrence rates are high after medication is discontinued – and there is concern among some experts that hormone therapy may not keep the disease from progressing. In adolescents, there is concern about the significant side effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, which are sometimes chosen if COCPs and NSAIDs fail to relieve symptoms. COCPs themselves may be problematic, causing premature closure of growth plates.

And when it comes to surgical treatment, there’s often sharp debate over which operative approaches are best for endometriosis. Advocates of excision – including many of the patient advocacy groups – say that ablation too often causes scar tissue and leaves behind disease, leading to recurrent symptoms and multiple surgeries. Critics of excisional surgery express concern about excision-induced adhesions and scar tissue, and about some excisional surgery being too “radical,” particularly when it is performed for earlier-stage disease in adolescents. Research is limited, comprised largely of small retrospective reports and single-institution cohort studies.

Meredith Loveless, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist who chairs ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care, is leading the development of a new ACOG committee opinion on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in adolescents. The laparoscopic appearance of endometriosis in young patients and the need “for fertility preservation as a priority” in surgery will be among the points discussed in ACOG’s upcoming guidance, she said.

“Somebody who manages adult endometriosis and who does extremely aggressive surgical work may actually be harming an adolescent rather than helping them,” said Dr. Loveless of the Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. (Dr. Loveless has also worked with the American Academy of Pediatrics and notes that the academy provides education on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis as part of its national conference.)

Nicole Donnellan, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Magee–Womens Hospital, said that fertility preservation is always a goal – and is possible – regardless of age. “A lot of us who are advanced laparoscopic surgeons are passionate about excision because (with other approaches) you’re not fully exploring the extent of the disease – what’s behind the superficial things you see,” she said. “Whether you’re 38 and wanting to preserve your fertility, or whether you’re 18, I’m still going to use the same approach. I want to make sure you have a functioning tube, ovaries, and uterus.”

Ken R. Sinervo, MD, medical director of the Center for Endometriosis Care in Atlanta, which has followed patients postsurgically for an average of 7-8 years, said adhesions can occur "whether you're ablating the disease or excising it," and that in his excisional surgeries, he successfully prevents adhesion formation with the use of various intraoperative adhesion barriers as well as bioregenerative medicine to facilitate healing. The key to avoiding repeat surgeries is to "remove all the disease that is present," he emphasized, adding that the "great majority of young patients will have peritoneal disease and very little ovarian involvement."*

ACOG under fire

Dr. Sinervo and Dr. Orbuch are among the gynecologic surgeons, other providers, and patients who have signed a petition to ACOG urging it to involve both educated patients and expert, multidisciplinary endometriosis providers in improving their guidance and policies on endometriosis to facilitate earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

The petition was organized by advocate Casey Berna in July and supported by more than a half-dozen endometriosis advocacy groups; in early May, it had almost 8,700 signatures. Ms. Berna also co-organized a demonstration outside ACOG headquarters on April 5-6 as leaders were reviewing practice bulletins and deciding which need revision – and a virtual protest (#WeMatterACOG) – to push for better guidelines.

Ms. Berna, Ms. Cohn, and others have also expressed concern that ob.gyns.’ management of endometriosis – and the development of guidelines – is colored by financial conflicts of interest. The petition, moreover, calls upon ACOG to help create coding specific for excision surgery; currently, because of the lack of reimbursement, many surgeons operate out of network and patients struggle with treatment costs.

In a statement issued in response to the protests, ACOG chief executive officer and executive vice president Hal Lawrence, MD, said that “ACOG is aware of the sensitivities and concerns surrounding timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. We are always working diligently to review all the available literature and ensure that our guidance to members is accurate and up to date. It’s our aim that [diagnosis and care] are both evidence based and patient centered. To that end, we recognize that patient voices and advocacy are an important part of ensuring we are meeting these high standards.”

In an interview before the protests, Dr. Lawrence said the Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology will revise its guidelines on the management of endometriosis, which were last revised in 2010 and reaffirmed in 2016. He said that he had spoken at length with Ms. Berna on the phone and had passed on a file of research and other materials to the Committee for their consideration.

On April 5, ACOG also joined the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and seven other organizations in sending a letter to the U.S. Senate and House calling for more research on and attention to the disease. NIH research dollars for the disease have dropped from $16 million in 2010 to $7 million in 2018, and “there are too few treatment options available to patients,” the letter says. “We urge you to [prioritize endometriosis] as an important women’s health issue.”

*This article was updated June 5, 2018. An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Ken R. Sinervo’s name.

Meg Hayden, RN, a school nurse in Oxford, Miss., used to be a labor and delivery nurse and considers herself more attuned to women’s health issues than other school nurses are. Still, a new educational initiative on endometriosis that stresses that menstrual pain is not normal – and that teenagers are not too young to have endometriosis – has helped her “connect the dots.”

“It’s a good reminder for me to look at patterns” and advise those girls who have repeated episodes of pelvic pain and other symptoms to “keep a diary” and to seek care, Ms. Hayden said.

They are demanding that serious diagnostic delays be rectified – that disease symptoms be better recognized by gynecologists, pediatricians, and other primary care physicians – and then, that the disease be better managed.

Some of the advocacy groups have petitioned the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to involve patients and endometriosis experts in creating new standards of care. And at press time, activist Shannon Cohn, who developed the School Nurse initiative after producing a documentary film titled Endo What?, was working with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) on finalizing plans for a national public service announcement campaign. (Sen. Hatch wrote an opinion piece for CNN in late March describing his granddaughter’s experience with the disease and calling the widespread prevalence of the disease – and the lack of any long-term treatment options – “nothing short of a public health emergency.”)

Estimates vary, but the average interval between presentation of symptoms and definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy (and usually) biopsy is commonly reported as 7-10 years. The disease can cause incapacitating pain, missed days of school and work, and increasing morbidities over time, including infertility and organ damage both inside and outside the pelvic cavity. A majority of women with endometriosis – two-thirds, according to one survey of more than 4,300 women with surgically diagnosed disease (Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9) – report first experiencing symptoms during adolescence.

Yet, too often, adolescents believe or are told that “periods are supposed to hurt,” and other symptoms of the disease – such as gastrointestinal symptoms – are overlooked.

“If we can diagnose endometriosis in its early stages, we could prevent a lifetime of pain and suffering, and decrease rates of infertility ... hopefully stopping disease progression before it does damage,” said Marc R. Laufer, MD, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. “If we don’t, we’re missing a huge opportunity because we know that endometriosis affects 10% of women.”

Atypical symptoms and presentation

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. It traditionally has been associated with retrograde menstruation, but today, there are more nuanced and likely overlapping theories of etiology. Identified in girls even prior to the onset of menses, the disease is generally believed to be progressive, but perhaps not all the time. Patients with significant amounts of disease may have tremendous pain or they may have very little discomfort.

While adolescents can have advanced endometriosis, most have early-stage disease, experts say. Still, adolescence offers its own complexities. Preteen and teen patients with endometriosis tend to present more often with atypical symptoms and with much more subtle and variable laparoscopic findings than do adult patients. Dr. Laufer reported more than 20 years ago that only 9.7% of 46 girls presented classically with dysmenorrhea. In 63%, pain was both acyclic and cyclic, and in 28%, pain was acyclic only (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199-202).

In a more recent report on adolescents treated by gynecologic surgeon Ceana Nezhat, MD, 64% had dysmenorrhea, 44% had menorrhagia, 60% had abnormal or irregular uterine bleeding, 56% had at least one gastrointestinal symptom, and 52% had at least one genitourinary symptom. The girls had seen a mean of three physicians, including psychiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, and had received diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, appendicitis, ovarian cysts, and musculoskeletal pain (JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00019). Notably, 56% had a family history of endometriosis, Dr. Nezhat, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, and his colleagues found.

To address levels of pain, Dr. Laufer usually asks young women if they feel they’re at a disadvantage to other young women or to men. This opens the door to learning more about school absences, missed activities, and decreased quality of life. Pain, he emphasizes, is only part of the picture. “It’s also about fatigue and energy levels, social interaction, depression, sexual function if they’re sexually active, body image issues, and bowel and bladder functionality.”

If the new generation of school nurse programs and other educational initiatives are successful, teens will increasingly come to appointments with notes in hand. Ms. Hayden counsels students on what to discuss with the doctor. And high school students in New York who have been educated through the Endometriosis Foundation of America’s 5-year-old ENPOWR Project for endometriosis education are urged to keep a journal or use a symptom tracker app if they are experiencing pain or other symptoms associated with endometriosis.

“We tell them that, with a record, you can show that the second week of every month I’m in terrible pain, for instance, or I’ve fainted twice in the last month, or here’s when my nausea is really aggressive,” said Nina Baker, outreach coordinator for the foundation. “We’re very honest about how often this is dismissed ... and we assure them that by no means are you wrong about your pain.”

ENPOWR lessons have been taught in more than 165 schools thus far (mostly in health classes in New York schools and largely by foundation-trained educators), and a recently developed online package of educational materials for schools – the Endo EduKit – is expanding the foundation’s geographical reach to other states. Students are encouraged during the training to see a gynecologist if they’re concerned about endometriosis, Ms. Baker said.

In Mississippi, Ms. Hayden suggests that younger high-schoolers see their pediatrician, but after that, “I feel like they should go to the gynecologist.” (ACOG recommends a first visit to the gynecologist between the ages of 13 and 15 for anticipatory guidance.) The year-old School Nurse Initiative has sent toolkits, posters, and DVD copies of the “Endo What?” film to nurses in 652 schools thus far. “Our goal,” said Ms. Cohn, a lawyer, filmmaker, and an endometriosis patient, “is to educate every school nurse in middle and high schools across the country.”

Treatment dilemmas

The first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea and for suspected endometriosis in adolescents has long been empiric treatment with NSAIDs and oral contraceptive pills. Experts commonly recommend today that combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) be started cyclically and then changed to continuous dosing if necessary with the goal of inducing amenorrhea.

If symptoms are not well controlled within 3-6 months of compliant medication management with COCPs and NSAIDs and endometriosis is suspected, then laparoscopy by a physician who is familiar with adolescent endometriosis and can simultaneously diagnose and treat the disease should be considered, according to Dr. Laufer and several other experts in pediatric and adolescent gynecology who spoke with Ob.Gyn. News.

“If someone still has pain on one COCP, then switching to another COCP is not going to solve the problem – there is no study that shows that one pill is better than another,” Dr. Laufer said.

Yet extra months and sometimes years of pill-switching and empiric therapy with other medications – rather than surgical evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment – is not uncommon. “Usually, by the time a patient comes to me, they’ve already been on multiple birth control pills, they’ve failed NSAIDs, and they’ve often tried other medications as well,” such as progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, said Iris Kerin Orbuch, MD, director of the Advanced Gynecologic Laparoscopy Centers in New York and Los Angeles.

Some also have had diagnostic laparoscopies and been wrongly told that nothing is wrong. Endometriosis is “not all powder-burn lesions and chocolate cysts, which is what we’re taught in medical school,” she said. “It can have many appearances, especially in teens and adolescents. It can be clear vesicles, white, fibrotic, yellow, blue, and brown ... and quite commonly there can simply be areas of increased vascularity. I only learned this in my fellowship.”

Dr. Orbuch, who routinely treats adolescents with endometriosis, takes a holistic approach to the disease that includes working with patients – often before surgery and in partnership with other providers – to downregulate the central nervous system and to alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction that often develops secondary to the disease. When she does operate and finds endometriosis, she performs excisional surgery, in contrast with ablative techniques such as cauterization or desiccation that are used by many physicians.

Treatment of endometriosis is rife with dilemmas, controversies, and shortcomings. Medical treatments can improve pain, but as ACOG’s current Practice Bulletin (No. 114) points out, recurrence rates are high after medication is discontinued – and there is concern among some experts that hormone therapy may not keep the disease from progressing. In adolescents, there is concern about the significant side effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, which are sometimes chosen if COCPs and NSAIDs fail to relieve symptoms. COCPs themselves may be problematic, causing premature closure of growth plates.

And when it comes to surgical treatment, there’s often sharp debate over which operative approaches are best for endometriosis. Advocates of excision – including many of the patient advocacy groups – say that ablation too often causes scar tissue and leaves behind disease, leading to recurrent symptoms and multiple surgeries. Critics of excisional surgery express concern about excision-induced adhesions and scar tissue, and about some excisional surgery being too “radical,” particularly when it is performed for earlier-stage disease in adolescents. Research is limited, comprised largely of small retrospective reports and single-institution cohort studies.

Meredith Loveless, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist who chairs ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care, is leading the development of a new ACOG committee opinion on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in adolescents. The laparoscopic appearance of endometriosis in young patients and the need “for fertility preservation as a priority” in surgery will be among the points discussed in ACOG’s upcoming guidance, she said.

“Somebody who manages adult endometriosis and who does extremely aggressive surgical work may actually be harming an adolescent rather than helping them,” said Dr. Loveless of the Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. (Dr. Loveless has also worked with the American Academy of Pediatrics and notes that the academy provides education on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis as part of its national conference.)

Nicole Donnellan, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Magee–Womens Hospital, said that fertility preservation is always a goal – and is possible – regardless of age. “A lot of us who are advanced laparoscopic surgeons are passionate about excision because (with other approaches) you’re not fully exploring the extent of the disease – what’s behind the superficial things you see,” she said. “Whether you’re 38 and wanting to preserve your fertility, or whether you’re 18, I’m still going to use the same approach. I want to make sure you have a functioning tube, ovaries, and uterus.”

Ken R. Sinervo, MD, medical director of the Center for Endometriosis Care in Atlanta, which has followed patients postsurgically for an average of 7-8 years, said adhesions can occur "whether you're ablating the disease or excising it," and that in his excisional surgeries, he successfully prevents adhesion formation with the use of various intraoperative adhesion barriers as well as bioregenerative medicine to facilitate healing. The key to avoiding repeat surgeries is to "remove all the disease that is present," he emphasized, adding that the "great majority of young patients will have peritoneal disease and very little ovarian involvement."*

ACOG under fire

Dr. Sinervo and Dr. Orbuch are among the gynecologic surgeons, other providers, and patients who have signed a petition to ACOG urging it to involve both educated patients and expert, multidisciplinary endometriosis providers in improving their guidance and policies on endometriosis to facilitate earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

The petition was organized by advocate Casey Berna in July and supported by more than a half-dozen endometriosis advocacy groups; in early May, it had almost 8,700 signatures. Ms. Berna also co-organized a demonstration outside ACOG headquarters on April 5-6 as leaders were reviewing practice bulletins and deciding which need revision – and a virtual protest (#WeMatterACOG) – to push for better guidelines.

Ms. Berna, Ms. Cohn, and others have also expressed concern that ob.gyns.’ management of endometriosis – and the development of guidelines – is colored by financial conflicts of interest. The petition, moreover, calls upon ACOG to help create coding specific for excision surgery; currently, because of the lack of reimbursement, many surgeons operate out of network and patients struggle with treatment costs.

In a statement issued in response to the protests, ACOG chief executive officer and executive vice president Hal Lawrence, MD, said that “ACOG is aware of the sensitivities and concerns surrounding timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. We are always working diligently to review all the available literature and ensure that our guidance to members is accurate and up to date. It’s our aim that [diagnosis and care] are both evidence based and patient centered. To that end, we recognize that patient voices and advocacy are an important part of ensuring we are meeting these high standards.”

In an interview before the protests, Dr. Lawrence said the Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology will revise its guidelines on the management of endometriosis, which were last revised in 2010 and reaffirmed in 2016. He said that he had spoken at length with Ms. Berna on the phone and had passed on a file of research and other materials to the Committee for their consideration.

On April 5, ACOG also joined the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and seven other organizations in sending a letter to the U.S. Senate and House calling for more research on and attention to the disease. NIH research dollars for the disease have dropped from $16 million in 2010 to $7 million in 2018, and “there are too few treatment options available to patients,” the letter says. “We urge you to [prioritize endometriosis] as an important women’s health issue.”

*This article was updated June 5, 2018. An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Ken R. Sinervo’s name.

Meg Hayden, RN, a school nurse in Oxford, Miss., used to be a labor and delivery nurse and considers herself more attuned to women’s health issues than other school nurses are. Still, a new educational initiative on endometriosis that stresses that menstrual pain is not normal – and that teenagers are not too young to have endometriosis – has helped her “connect the dots.”

“It’s a good reminder for me to look at patterns” and advise those girls who have repeated episodes of pelvic pain and other symptoms to “keep a diary” and to seek care, Ms. Hayden said.

They are demanding that serious diagnostic delays be rectified – that disease symptoms be better recognized by gynecologists, pediatricians, and other primary care physicians – and then, that the disease be better managed.

Some of the advocacy groups have petitioned the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to involve patients and endometriosis experts in creating new standards of care. And at press time, activist Shannon Cohn, who developed the School Nurse initiative after producing a documentary film titled Endo What?, was working with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) on finalizing plans for a national public service announcement campaign. (Sen. Hatch wrote an opinion piece for CNN in late March describing his granddaughter’s experience with the disease and calling the widespread prevalence of the disease – and the lack of any long-term treatment options – “nothing short of a public health emergency.”)

Estimates vary, but the average interval between presentation of symptoms and definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy (and usually) biopsy is commonly reported as 7-10 years. The disease can cause incapacitating pain, missed days of school and work, and increasing morbidities over time, including infertility and organ damage both inside and outside the pelvic cavity. A majority of women with endometriosis – two-thirds, according to one survey of more than 4,300 women with surgically diagnosed disease (Fertil Steril. 2009;91:32-9) – report first experiencing symptoms during adolescence.

Yet, too often, adolescents believe or are told that “periods are supposed to hurt,” and other symptoms of the disease – such as gastrointestinal symptoms – are overlooked.

“If we can diagnose endometriosis in its early stages, we could prevent a lifetime of pain and suffering, and decrease rates of infertility ... hopefully stopping disease progression before it does damage,” said Marc R. Laufer, MD, chief of gynecology at Boston Children’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston. “If we don’t, we’re missing a huge opportunity because we know that endometriosis affects 10% of women.”

Atypical symptoms and presentation

Endometriosis is an enigmatic disease. It traditionally has been associated with retrograde menstruation, but today, there are more nuanced and likely overlapping theories of etiology. Identified in girls even prior to the onset of menses, the disease is generally believed to be progressive, but perhaps not all the time. Patients with significant amounts of disease may have tremendous pain or they may have very little discomfort.

While adolescents can have advanced endometriosis, most have early-stage disease, experts say. Still, adolescence offers its own complexities. Preteen and teen patients with endometriosis tend to present more often with atypical symptoms and with much more subtle and variable laparoscopic findings than do adult patients. Dr. Laufer reported more than 20 years ago that only 9.7% of 46 girls presented classically with dysmenorrhea. In 63%, pain was both acyclic and cyclic, and in 28%, pain was acyclic only (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199-202).

In a more recent report on adolescents treated by gynecologic surgeon Ceana Nezhat, MD, 64% had dysmenorrhea, 44% had menorrhagia, 60% had abnormal or irregular uterine bleeding, 56% had at least one gastrointestinal symptom, and 52% had at least one genitourinary symptom. The girls had seen a mean of three physicians, including psychiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, and had received diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome, dysmenorrhea, appendicitis, ovarian cysts, and musculoskeletal pain (JSLS. 2015;19:e2015.00019). Notably, 56% had a family history of endometriosis, Dr. Nezhat, of the Atlanta Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, and his colleagues found.

To address levels of pain, Dr. Laufer usually asks young women if they feel they’re at a disadvantage to other young women or to men. This opens the door to learning more about school absences, missed activities, and decreased quality of life. Pain, he emphasizes, is only part of the picture. “It’s also about fatigue and energy levels, social interaction, depression, sexual function if they’re sexually active, body image issues, and bowel and bladder functionality.”

If the new generation of school nurse programs and other educational initiatives are successful, teens will increasingly come to appointments with notes in hand. Ms. Hayden counsels students on what to discuss with the doctor. And high school students in New York who have been educated through the Endometriosis Foundation of America’s 5-year-old ENPOWR Project for endometriosis education are urged to keep a journal or use a symptom tracker app if they are experiencing pain or other symptoms associated with endometriosis.

“We tell them that, with a record, you can show that the second week of every month I’m in terrible pain, for instance, or I’ve fainted twice in the last month, or here’s when my nausea is really aggressive,” said Nina Baker, outreach coordinator for the foundation. “We’re very honest about how often this is dismissed ... and we assure them that by no means are you wrong about your pain.”

ENPOWR lessons have been taught in more than 165 schools thus far (mostly in health classes in New York schools and largely by foundation-trained educators), and a recently developed online package of educational materials for schools – the Endo EduKit – is expanding the foundation’s geographical reach to other states. Students are encouraged during the training to see a gynecologist if they’re concerned about endometriosis, Ms. Baker said.

In Mississippi, Ms. Hayden suggests that younger high-schoolers see their pediatrician, but after that, “I feel like they should go to the gynecologist.” (ACOG recommends a first visit to the gynecologist between the ages of 13 and 15 for anticipatory guidance.) The year-old School Nurse Initiative has sent toolkits, posters, and DVD copies of the “Endo What?” film to nurses in 652 schools thus far. “Our goal,” said Ms. Cohn, a lawyer, filmmaker, and an endometriosis patient, “is to educate every school nurse in middle and high schools across the country.”

Treatment dilemmas

The first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea and for suspected endometriosis in adolescents has long been empiric treatment with NSAIDs and oral contraceptive pills. Experts commonly recommend today that combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs) be started cyclically and then changed to continuous dosing if necessary with the goal of inducing amenorrhea.

If symptoms are not well controlled within 3-6 months of compliant medication management with COCPs and NSAIDs and endometriosis is suspected, then laparoscopy by a physician who is familiar with adolescent endometriosis and can simultaneously diagnose and treat the disease should be considered, according to Dr. Laufer and several other experts in pediatric and adolescent gynecology who spoke with Ob.Gyn. News.

“If someone still has pain on one COCP, then switching to another COCP is not going to solve the problem – there is no study that shows that one pill is better than another,” Dr. Laufer said.

Yet extra months and sometimes years of pill-switching and empiric therapy with other medications – rather than surgical evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment – is not uncommon. “Usually, by the time a patient comes to me, they’ve already been on multiple birth control pills, they’ve failed NSAIDs, and they’ve often tried other medications as well,” such as progestins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, said Iris Kerin Orbuch, MD, director of the Advanced Gynecologic Laparoscopy Centers in New York and Los Angeles.

Some also have had diagnostic laparoscopies and been wrongly told that nothing is wrong. Endometriosis is “not all powder-burn lesions and chocolate cysts, which is what we’re taught in medical school,” she said. “It can have many appearances, especially in teens and adolescents. It can be clear vesicles, white, fibrotic, yellow, blue, and brown ... and quite commonly there can simply be areas of increased vascularity. I only learned this in my fellowship.”

Dr. Orbuch, who routinely treats adolescents with endometriosis, takes a holistic approach to the disease that includes working with patients – often before surgery and in partnership with other providers – to downregulate the central nervous system and to alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction that often develops secondary to the disease. When she does operate and finds endometriosis, she performs excisional surgery, in contrast with ablative techniques such as cauterization or desiccation that are used by many physicians.

Treatment of endometriosis is rife with dilemmas, controversies, and shortcomings. Medical treatments can improve pain, but as ACOG’s current Practice Bulletin (No. 114) points out, recurrence rates are high after medication is discontinued – and there is concern among some experts that hormone therapy may not keep the disease from progressing. In adolescents, there is concern about the significant side effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, which are sometimes chosen if COCPs and NSAIDs fail to relieve symptoms. COCPs themselves may be problematic, causing premature closure of growth plates.

And when it comes to surgical treatment, there’s often sharp debate over which operative approaches are best for endometriosis. Advocates of excision – including many of the patient advocacy groups – say that ablation too often causes scar tissue and leaves behind disease, leading to recurrent symptoms and multiple surgeries. Critics of excisional surgery express concern about excision-induced adhesions and scar tissue, and about some excisional surgery being too “radical,” particularly when it is performed for earlier-stage disease in adolescents. Research is limited, comprised largely of small retrospective reports and single-institution cohort studies.

Meredith Loveless, MD, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist who chairs ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care, is leading the development of a new ACOG committee opinion on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in adolescents. The laparoscopic appearance of endometriosis in young patients and the need “for fertility preservation as a priority” in surgery will be among the points discussed in ACOG’s upcoming guidance, she said.

“Somebody who manages adult endometriosis and who does extremely aggressive surgical work may actually be harming an adolescent rather than helping them,” said Dr. Loveless of the Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. (Dr. Loveless has also worked with the American Academy of Pediatrics and notes that the academy provides education on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis as part of its national conference.)

Nicole Donnellan, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Magee–Womens Hospital, said that fertility preservation is always a goal – and is possible – regardless of age. “A lot of us who are advanced laparoscopic surgeons are passionate about excision because (with other approaches) you’re not fully exploring the extent of the disease – what’s behind the superficial things you see,” she said. “Whether you’re 38 and wanting to preserve your fertility, or whether you’re 18, I’m still going to use the same approach. I want to make sure you have a functioning tube, ovaries, and uterus.”

Ken R. Sinervo, MD, medical director of the Center for Endometriosis Care in Atlanta, which has followed patients postsurgically for an average of 7-8 years, said adhesions can occur "whether you're ablating the disease or excising it," and that in his excisional surgeries, he successfully prevents adhesion formation with the use of various intraoperative adhesion barriers as well as bioregenerative medicine to facilitate healing. The key to avoiding repeat surgeries is to "remove all the disease that is present," he emphasized, adding that the "great majority of young patients will have peritoneal disease and very little ovarian involvement."*

ACOG under fire

Dr. Sinervo and Dr. Orbuch are among the gynecologic surgeons, other providers, and patients who have signed a petition to ACOG urging it to involve both educated patients and expert, multidisciplinary endometriosis providers in improving their guidance and policies on endometriosis to facilitate earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

The petition was organized by advocate Casey Berna in July and supported by more than a half-dozen endometriosis advocacy groups; in early May, it had almost 8,700 signatures. Ms. Berna also co-organized a demonstration outside ACOG headquarters on April 5-6 as leaders were reviewing practice bulletins and deciding which need revision – and a virtual protest (#WeMatterACOG) – to push for better guidelines.

Ms. Berna, Ms. Cohn, and others have also expressed concern that ob.gyns.’ management of endometriosis – and the development of guidelines – is colored by financial conflicts of interest. The petition, moreover, calls upon ACOG to help create coding specific for excision surgery; currently, because of the lack of reimbursement, many surgeons operate out of network and patients struggle with treatment costs.

In a statement issued in response to the protests, ACOG chief executive officer and executive vice president Hal Lawrence, MD, said that “ACOG is aware of the sensitivities and concerns surrounding timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. We are always working diligently to review all the available literature and ensure that our guidance to members is accurate and up to date. It’s our aim that [diagnosis and care] are both evidence based and patient centered. To that end, we recognize that patient voices and advocacy are an important part of ensuring we are meeting these high standards.”

In an interview before the protests, Dr. Lawrence said the Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology will revise its guidelines on the management of endometriosis, which were last revised in 2010 and reaffirmed in 2016. He said that he had spoken at length with Ms. Berna on the phone and had passed on a file of research and other materials to the Committee for their consideration.

On April 5, ACOG also joined the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and seven other organizations in sending a letter to the U.S. Senate and House calling for more research on and attention to the disease. NIH research dollars for the disease have dropped from $16 million in 2010 to $7 million in 2018, and “there are too few treatment options available to patients,” the letter says. “We urge you to [prioritize endometriosis] as an important women’s health issue.”

*This article was updated June 5, 2018. An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Ken R. Sinervo’s name.