User login

History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

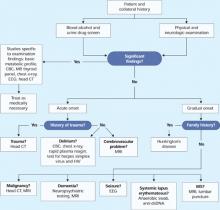

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.

Within 4 days of starting risperidone, Ms. B’s auditory hallucinations and paranoia have lessened and her insight is improved. We recommend increasing the dosage to 2 mg/d because we feel that 1 mg/d will not sufficiently control her symptoms. She remains paranoid but is reluctant to increase the dosage for fear of adverse effects, though she has reported none so far.

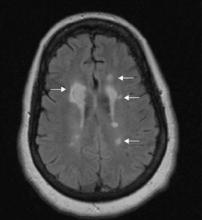

Brain MRI taken the night Ms. B was admitted shows:

- multiple focal, well-defined hyperintense periventricular lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)- and T2-weighted images (Figure 2). Some lesions are flame-shaped.

- a 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to the right frontal horn showing a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images without contrast enhancement. White-matter edema surrounds this lesion.

- no gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Two radiologists confirm possible demyelination, suggesting multiple sclerosis (MS). Final report of initial brain CT shows lowdensity, periventricular white matter changes consistent with the MRI findings.

Results of subsequent laboratory tests are normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is slightly elevated at 35 mm/hr, suggesting a possible autoimmune disorder. ECG shows sinus bradycardia, and chest x-ray and MR angiogram are unremarkable, as are EEG and visual evoked potential results.

Lumbar puncture and CSF studies show increased immunoglobulin G to albumin ratio. CSF fluid is clear, blood counts and protein are normal, Gram’s stain and culture are negative, and cytologic findings show a marked increase in mature lymphocytes. These results suggest inflammation, but follow-up neurologic exam is unremarkable.

Figure 2 FLAIR-weighted image after Ms. B’s brain MRI

Right 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to right frontal horn and multiple left hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted image.

The authors’ observations

Determining disease dissemination in time and space is key to diagnosing MS. Clinical presentation or MRI can determine both criteria (Table 1). Ms. B’s lesions and CSF results suggest that MS has disseminated throughout her body, but neurologic examination shows no objective clinical evidence of lesions.

Neuropsychological testing might help evaluate Ms. B’s cognition and executive functioning, but these deficits do not specifically suggest MS. The cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, is believed to coordinate organization, planning, and socially appropriate behavior. MS typically involves white matter rather than the cortex, but researchers have suggested that MS-related demyelination might disrupt the axonal circuits that connect the cortex to other brain areas.18

Increased lesion load has been correlated with decreased cognitive function. Neuropsychological testing could indirectly point to a lesion load increase by recording decreased cognitive function, but this decline cannot be attributed to MS without an MRI.

Ms. B’s psychotic symptoms could be clinical evidence of MS, but we cannot solidify the diagnosis until we establish dissemination in time. To do that, we need a second MRI 3 months after the first one. Concurrent late-onset paraphrenia and MS is possible but rare.

Table 1

Findings needed to determine MS diagnosis based on clinical presentation

| Clinical presentation | Findings needed for MS diagnosis |

|---|---|

| >2 clinical attacks* Objective clinical evidence of >2 lesions | None |

| >2 clinical attacks Objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| or | |

| Await further attack implicating a different site | |

| 1 clinical attack >2 objective clinical lesions | Dissemination in time by MRI |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| 1 clinical attack 1 objective clinical lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| and | |

| Dissemination in time by MRI | |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| * Clinical attack: neurologic disturbance defined by subjective report or objective observation lasting at least 24 hours. | |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

Follow-up: where is she?

Ms. B is discharged after 10 days. She denies hallucinations, and staff notices decreased paranoia, brighter affect, and improved insight. We tell her to continue taking risperidone, 1 mg/d.

Three weeks later, Ms. B sees an outpatient psychiatrist. She is paranoid, guarded, and has not been taking risperidone.

Because Ms. B’s previous MRI results are suspect, we ask the hospital’s neurology service to examine her. Findings are unremarkable, but the neurologist recommends a followup brain MRI in 3 months or sooner if symptoms emerge. More than 2 years later, she has not completed a second MRI or contacted her psychiatrist or neurologist.

The authors’ observations

Ms. B’s case highlights the importance of:

- recognizing an atypical presentation of a primary psychotic disorder

- checking for a medical cause of psychosis (Table 2)

- knowing which psychiatric symptoms are common in MS.

Despite absence of neurologic symptoms, Ms. B’s psychosis could have been the initial presentation of MS, which is more prevalent among psychiatric inpatients than in the general population.6,7 In a prospective study,8 95% of patients with MS had neuropsychiatric symptoms, and 79% had depressive symptoms. Hallucinations and delusions were reported in 10% and 7% of MS patients, respectively. These findings suggest that mood disturbances are considerably more common than psychosis among patients with MS.

Diagnosis of MSrelated psychosis has been addressed only in case reports or small studies, most of which have not clearly defined psychosis or adequately described the symptoms or confounding factors such as medications. Findings on prevalence of psychosis as the initial presentation in MS are more limited and confounded by instances in which neurologic symptoms might have been overlooked.9,11

Few studies have investigated whether lesion location correlates with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms. In one study,8 brain MRI taken within 9 months of presenting symptoms showed that MS was not significantly more severe among patients with psychosis compared with nonpsychotic MS patients. These data support psychosis as a possible early finding in MS.

At least two studies12,13 suggest a correlation between temporal lobe lesions and psychosis, but both study samples were small (8 and 10 patients) and used a combination of diagnoses. One case report also supports this correlation.14

Table 2

Medical conditions that can cause psychotic symptoms

| Cerebral malignancy (primary and metastases) | |

| Cerebral trauma | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | |

| Delirium | |

| Dementia | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Huntington's disease | |

| Infection | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Parkinson's disease | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

Treating ms-related psychosis

MS-related psychosis should abate with MS treatment, but no systematized studies have verified this or determined which antipsychotics would be suitable. Single case reports suggest successful treatment with risperidone,13 haloperidol,15 clozapine,16 or ziprasidone.17 Ms. B showed initial improvement with risperidone, but because she was lost to follow-up we cannot say if this medication would work long-term.

Related resources

- Feinstein A. The clinical neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. www.nationalmssociety.org.

Drug brand name

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosures

Dr. Higgins reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rafeyan is a speaker for AstraZeneca, BristolMyers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth. He is also an advisor to Abbott Laboratories and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Kaplan B, Sadock V, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:1107,1299.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Howard R, Rabins P, Seeman M, Jeste D. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172-8.

4. Lautenschlager NT, Forstl H. Organic psychosis: insight into the biology of psychosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2001;3:319-25.

5. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121-7.

6. Pine D, Douglas C, Charles E, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis presenting to psychiatric hospitals. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:297-306.

7. Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, Renshaw PF. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:54-9.

8. Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, Garcia de la Cadena C. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:51-7.

9. Felgenhauer K. Psychiatric disorders in the encephalitic form of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 1990;237:11-8.

10. Skegg K, Corwin P, Skegg D. How often is multiple sclerosis mistaken for a psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med 1988;18:733-6.

11. Kohler J, Heilmeyer H, Volk B. Multiple sclerosis presenting as chronic atypical psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:281-4.

12. Honer G, Hurwitz T, Li D, et al. Temporal lobe involvement in multiple sclerosis patients with psychiatric disorders. Arch Neurol 1987;44:187-90.

13. Feinstein A, du Boulay G, Ron M. Psychotic illness in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry 1992;161:680-5.

14. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:27-33.

15. Drake ME. Acute paranoid psychosis in multiple sclerosis. Psychosomatics 1984;25:60-3.

16. Chong SA, Ko SM. Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:90-1.

17. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004;28:743-4.

18. Asghar-Ali A, Taber K, Hurley R, Hayman L. Pure neuropsychiatric presentation of multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:226-31.

History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.

Within 4 days of starting risperidone, Ms. B’s auditory hallucinations and paranoia have lessened and her insight is improved. We recommend increasing the dosage to 2 mg/d because we feel that 1 mg/d will not sufficiently control her symptoms. She remains paranoid but is reluctant to increase the dosage for fear of adverse effects, though she has reported none so far.

Brain MRI taken the night Ms. B was admitted shows:

- multiple focal, well-defined hyperintense periventricular lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)- and T2-weighted images (Figure 2). Some lesions are flame-shaped.

- a 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to the right frontal horn showing a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images without contrast enhancement. White-matter edema surrounds this lesion.

- no gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Two radiologists confirm possible demyelination, suggesting multiple sclerosis (MS). Final report of initial brain CT shows lowdensity, periventricular white matter changes consistent with the MRI findings.

Results of subsequent laboratory tests are normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is slightly elevated at 35 mm/hr, suggesting a possible autoimmune disorder. ECG shows sinus bradycardia, and chest x-ray and MR angiogram are unremarkable, as are EEG and visual evoked potential results.

Lumbar puncture and CSF studies show increased immunoglobulin G to albumin ratio. CSF fluid is clear, blood counts and protein are normal, Gram’s stain and culture are negative, and cytologic findings show a marked increase in mature lymphocytes. These results suggest inflammation, but follow-up neurologic exam is unremarkable.

Figure 2 FLAIR-weighted image after Ms. B’s brain MRI

Right 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to right frontal horn and multiple left hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted image.

The authors’ observations

Determining disease dissemination in time and space is key to diagnosing MS. Clinical presentation or MRI can determine both criteria (Table 1). Ms. B’s lesions and CSF results suggest that MS has disseminated throughout her body, but neurologic examination shows no objective clinical evidence of lesions.

Neuropsychological testing might help evaluate Ms. B’s cognition and executive functioning, but these deficits do not specifically suggest MS. The cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, is believed to coordinate organization, planning, and socially appropriate behavior. MS typically involves white matter rather than the cortex, but researchers have suggested that MS-related demyelination might disrupt the axonal circuits that connect the cortex to other brain areas.18

Increased lesion load has been correlated with decreased cognitive function. Neuropsychological testing could indirectly point to a lesion load increase by recording decreased cognitive function, but this decline cannot be attributed to MS without an MRI.

Ms. B’s psychotic symptoms could be clinical evidence of MS, but we cannot solidify the diagnosis until we establish dissemination in time. To do that, we need a second MRI 3 months after the first one. Concurrent late-onset paraphrenia and MS is possible but rare.

Table 1

Findings needed to determine MS diagnosis based on clinical presentation

| Clinical presentation | Findings needed for MS diagnosis |

|---|---|

| >2 clinical attacks* Objective clinical evidence of >2 lesions | None |

| >2 clinical attacks Objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| or | |

| Await further attack implicating a different site | |

| 1 clinical attack >2 objective clinical lesions | Dissemination in time by MRI |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| 1 clinical attack 1 objective clinical lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| and | |

| Dissemination in time by MRI | |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| * Clinical attack: neurologic disturbance defined by subjective report or objective observation lasting at least 24 hours. | |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

Follow-up: where is she?

Ms. B is discharged after 10 days. She denies hallucinations, and staff notices decreased paranoia, brighter affect, and improved insight. We tell her to continue taking risperidone, 1 mg/d.

Three weeks later, Ms. B sees an outpatient psychiatrist. She is paranoid, guarded, and has not been taking risperidone.

Because Ms. B’s previous MRI results are suspect, we ask the hospital’s neurology service to examine her. Findings are unremarkable, but the neurologist recommends a followup brain MRI in 3 months or sooner if symptoms emerge. More than 2 years later, she has not completed a second MRI or contacted her psychiatrist or neurologist.

The authors’ observations

Ms. B’s case highlights the importance of:

- recognizing an atypical presentation of a primary psychotic disorder

- checking for a medical cause of psychosis (Table 2)

- knowing which psychiatric symptoms are common in MS.

Despite absence of neurologic symptoms, Ms. B’s psychosis could have been the initial presentation of MS, which is more prevalent among psychiatric inpatients than in the general population.6,7 In a prospective study,8 95% of patients with MS had neuropsychiatric symptoms, and 79% had depressive symptoms. Hallucinations and delusions were reported in 10% and 7% of MS patients, respectively. These findings suggest that mood disturbances are considerably more common than psychosis among patients with MS.

Diagnosis of MSrelated psychosis has been addressed only in case reports or small studies, most of which have not clearly defined psychosis or adequately described the symptoms or confounding factors such as medications. Findings on prevalence of psychosis as the initial presentation in MS are more limited and confounded by instances in which neurologic symptoms might have been overlooked.9,11

Few studies have investigated whether lesion location correlates with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms. In one study,8 brain MRI taken within 9 months of presenting symptoms showed that MS was not significantly more severe among patients with psychosis compared with nonpsychotic MS patients. These data support psychosis as a possible early finding in MS.

At least two studies12,13 suggest a correlation between temporal lobe lesions and psychosis, but both study samples were small (8 and 10 patients) and used a combination of diagnoses. One case report also supports this correlation.14

Table 2

Medical conditions that can cause psychotic symptoms

| Cerebral malignancy (primary and metastases) | |

| Cerebral trauma | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | |

| Delirium | |

| Dementia | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Huntington's disease | |

| Infection | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Parkinson's disease | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

Treating ms-related psychosis

MS-related psychosis should abate with MS treatment, but no systematized studies have verified this or determined which antipsychotics would be suitable. Single case reports suggest successful treatment with risperidone,13 haloperidol,15 clozapine,16 or ziprasidone.17 Ms. B showed initial improvement with risperidone, but because she was lost to follow-up we cannot say if this medication would work long-term.

Related resources

- Feinstein A. The clinical neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. www.nationalmssociety.org.

Drug brand name

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosures

Dr. Higgins reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rafeyan is a speaker for AstraZeneca, BristolMyers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth. He is also an advisor to Abbott Laboratories and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

History: shop talk

Ms. B, age 46, presents to the ER at her brother’s insistence. For about 6 months, she says, she has been “hearing voices”—including that of her boss—talking to each other about work.

Ms. B has no personal or family psychiatric history but notes that her sister died 6 months ago, and her father died the following month. At work, she is having trouble getting along with her boss. She adds that she has been skipping church lately because she believes her church is under investigation and the inquiry might be targeting her.

Ms. B has been a company manager for 20 years. She is divorced, has no children, and lives alone. She says she does not smoke or use illicit drugs and seldom drinks alcohol. She denies suicidal or homicidal thoughts, depressed mood, or visual hallucinations. She says she is sleeping only 3 to 4 hours nightly and feels fatigued in the afternoon. She denies loss of concentration or functioning.

Mental status. Ms. B is well groomed, maintains good eye contact, and is superficially cooperative but increasingly guarded with further questioning. She describes her mood as “OK,” but her affect is blunted. Thought process is logical but circumstantial at times, and her thoughts consist of auditory hallucinations, paranoid thinking, persecutory delusions, and ideas of reference. She has poor insight into her symptoms and does not want to be admitted.

Physical examination and laboratory tests are unremarkable. Negative ethanol and urine drug screens rule out substance abuse, and preliminary noncontrast head CT shows no acute changes.

The author’s observations

In women, schizophrenia typically emerges between ages 17 and 37;1 onset after age 45 is unusual.2 Ms. B’s age, family history, and lack of a formal thought disorder or negative symptoms make late-onset schizophrenia unlikely, though it cannot be ruled out.

Ms. B denies mood symptoms, but significant stressors—such as the recent deaths of her sister and father and difficulties at work—could precipitate a mood disorder. Of the possible diagnoses, major depressive disorder is most likely at this time.1,3 Because Ms. B’s symptoms do not clearly match any diagnosis, we speak with her brother and sister-in-law to seek collateral information.

Collateral history: beware of spies

Ms. B’s brother says his sister began behaving strangely about 8 months ago and has worsened lately. He says she suspects that her boss hired spies to watch her house, car, and her parent’s house. After work, she often parks in paid garages rather than at home to avoid being “followed.” When visiting, he says, she leaves her keys outside because she fears they contain a tracking device. Family members say Ms. B sometimes drops by at night—as late as 5 AM—complaining that she cannot sleep because she is being “watched.”

Ms. B’s family hired a private investigator 3 or 4 months ago to examine her house and car. Although no tracking devices were found, her brother says, Ms. B remains convinced she is being followed. He says she often speaks in “code” and whispers to herself.

According to her brother, Ms. B often hears voices while trying to sleep, saying such things as “Why won’t she turn over?” She reportedly wears a towel while showering because the “spies” are watching. During a conference she attended last week, she told her brother that a group of government investigators followed her there and arrested her boss.

Ms. B’s sister-in-law says the patient’s functioning has declined sharply, and that she has been helping Ms. B complete routine work. Neither she nor Ms. B’s brother have noticed a change in the patient’s energy, productivity, or speech production or speed, thus ruling out bipolar disorder. Ms. B’s brother confirms that there is no family history of mental illness.

The author’s observations

Collateral information about Ms. B points to psychosis rather than a mood disorder with psychotic features, but she lacks the formal thought disorder and negative symptoms common in primary psychotic disorders.

Because Ms. B’s presentation is atypical, we order brain MRI to check for a general medical condition (Figure 1). If brain MRI suggests a medical problem, we will follow with EEG, lumbar puncture, or other tests.

Figure 1 Clinical steps to rule out medical causes of late-onset psychosis

treatment, testing: what mri suggests

We admit Ms. B to the locked inpatient psychiatric unit—where she remains paranoid and guarded—and prescribe risperidone, 1 mg/d, to address her paranoia. She refuses medication at first because she feels she does not need psychiatric care, but we give her lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d for her anxiety, along with psychoeducation and family support. After 3 days, we stop lorazepam and Ms. B agrees to take risperidone.

Within 4 days of starting risperidone, Ms. B’s auditory hallucinations and paranoia have lessened and her insight is improved. We recommend increasing the dosage to 2 mg/d because we feel that 1 mg/d will not sufficiently control her symptoms. She remains paranoid but is reluctant to increase the dosage for fear of adverse effects, though she has reported none so far.

Brain MRI taken the night Ms. B was admitted shows:

- multiple focal, well-defined hyperintense periventricular lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)- and T2-weighted images (Figure 2). Some lesions are flame-shaped.

- a 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to the right frontal horn showing a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T1-weighted images without contrast enhancement. White-matter edema surrounds this lesion.

- no gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Two radiologists confirm possible demyelination, suggesting multiple sclerosis (MS). Final report of initial brain CT shows lowdensity, periventricular white matter changes consistent with the MRI findings.

Results of subsequent laboratory tests are normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is slightly elevated at 35 mm/hr, suggesting a possible autoimmune disorder. ECG shows sinus bradycardia, and chest x-ray and MR angiogram are unremarkable, as are EEG and visual evoked potential results.

Lumbar puncture and CSF studies show increased immunoglobulin G to albumin ratio. CSF fluid is clear, blood counts and protein are normal, Gram’s stain and culture are negative, and cytologic findings show a marked increase in mature lymphocytes. These results suggest inflammation, but follow-up neurologic exam is unremarkable.

Figure 2 FLAIR-weighted image after Ms. B’s brain MRI

Right 1.5-cm lesion adjacent to right frontal horn and multiple left hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-weighted image.

The authors’ observations

Determining disease dissemination in time and space is key to diagnosing MS. Clinical presentation or MRI can determine both criteria (Table 1). Ms. B’s lesions and CSF results suggest that MS has disseminated throughout her body, but neurologic examination shows no objective clinical evidence of lesions.

Neuropsychological testing might help evaluate Ms. B’s cognition and executive functioning, but these deficits do not specifically suggest MS. The cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, is believed to coordinate organization, planning, and socially appropriate behavior. MS typically involves white matter rather than the cortex, but researchers have suggested that MS-related demyelination might disrupt the axonal circuits that connect the cortex to other brain areas.18

Increased lesion load has been correlated with decreased cognitive function. Neuropsychological testing could indirectly point to a lesion load increase by recording decreased cognitive function, but this decline cannot be attributed to MS without an MRI.

Ms. B’s psychotic symptoms could be clinical evidence of MS, but we cannot solidify the diagnosis until we establish dissemination in time. To do that, we need a second MRI 3 months after the first one. Concurrent late-onset paraphrenia and MS is possible but rare.

Table 1

Findings needed to determine MS diagnosis based on clinical presentation

| Clinical presentation | Findings needed for MS diagnosis |

|---|---|

| >2 clinical attacks* Objective clinical evidence of >2 lesions | None |

| >2 clinical attacks Objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| or | |

| Await further attack implicating a different site | |

| 1 clinical attack >2 objective clinical lesions | Dissemination in time by MRI |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| 1 clinical attack 1 objective clinical lesion | Dissemination in space by MRI |

| or | |

| >2 MRI-detected lesions consistent with MS plus positive CSF | |

| and | |

| Dissemination in time by MRI | |

| or | |

| Second clinical attack | |

| * Clinical attack: neurologic disturbance defined by subjective report or objective observation lasting at least 24 hours. | |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

Follow-up: where is she?

Ms. B is discharged after 10 days. She denies hallucinations, and staff notices decreased paranoia, brighter affect, and improved insight. We tell her to continue taking risperidone, 1 mg/d.

Three weeks later, Ms. B sees an outpatient psychiatrist. She is paranoid, guarded, and has not been taking risperidone.

Because Ms. B’s previous MRI results are suspect, we ask the hospital’s neurology service to examine her. Findings are unremarkable, but the neurologist recommends a followup brain MRI in 3 months or sooner if symptoms emerge. More than 2 years later, she has not completed a second MRI or contacted her psychiatrist or neurologist.

The authors’ observations

Ms. B’s case highlights the importance of:

- recognizing an atypical presentation of a primary psychotic disorder

- checking for a medical cause of psychosis (Table 2)

- knowing which psychiatric symptoms are common in MS.

Despite absence of neurologic symptoms, Ms. B’s psychosis could have been the initial presentation of MS, which is more prevalent among psychiatric inpatients than in the general population.6,7 In a prospective study,8 95% of patients with MS had neuropsychiatric symptoms, and 79% had depressive symptoms. Hallucinations and delusions were reported in 10% and 7% of MS patients, respectively. These findings suggest that mood disturbances are considerably more common than psychosis among patients with MS.

Diagnosis of MSrelated psychosis has been addressed only in case reports or small studies, most of which have not clearly defined psychosis or adequately described the symptoms or confounding factors such as medications. Findings on prevalence of psychosis as the initial presentation in MS are more limited and confounded by instances in which neurologic symptoms might have been overlooked.9,11

Few studies have investigated whether lesion location correlates with specific neuropsychiatric symptoms. In one study,8 brain MRI taken within 9 months of presenting symptoms showed that MS was not significantly more severe among patients with psychosis compared with nonpsychotic MS patients. These data support psychosis as a possible early finding in MS.

At least two studies12,13 suggest a correlation between temporal lobe lesions and psychosis, but both study samples were small (8 and 10 patients) and used a combination of diagnoses. One case report also supports this correlation.14

Table 2

Medical conditions that can cause psychotic symptoms

| Cerebral malignancy (primary and metastases) | |

| Cerebral trauma | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | |

| Delirium | |

| Dementia | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Huntington's disease | |

| Infection | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Parkinson's disease | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

Treating ms-related psychosis

MS-related psychosis should abate with MS treatment, but no systematized studies have verified this or determined which antipsychotics would be suitable. Single case reports suggest successful treatment with risperidone,13 haloperidol,15 clozapine,16 or ziprasidone.17 Ms. B showed initial improvement with risperidone, but because she was lost to follow-up we cannot say if this medication would work long-term.

Related resources

- Feinstein A. The clinical neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. www.nationalmssociety.org.

Drug brand name

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosures

Dr. Higgins reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rafeyan is a speaker for AstraZeneca, BristolMyers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth. He is also an advisor to Abbott Laboratories and Forest Pharmaceuticals.

1. Kaplan B, Sadock V, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:1107,1299.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Howard R, Rabins P, Seeman M, Jeste D. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172-8.

4. Lautenschlager NT, Forstl H. Organic psychosis: insight into the biology of psychosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2001;3:319-25.

5. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121-7.

6. Pine D, Douglas C, Charles E, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis presenting to psychiatric hospitals. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:297-306.

7. Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, Renshaw PF. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:54-9.

8. Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, Garcia de la Cadena C. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:51-7.

9. Felgenhauer K. Psychiatric disorders in the encephalitic form of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 1990;237:11-8.

10. Skegg K, Corwin P, Skegg D. How often is multiple sclerosis mistaken for a psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med 1988;18:733-6.

11. Kohler J, Heilmeyer H, Volk B. Multiple sclerosis presenting as chronic atypical psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:281-4.

12. Honer G, Hurwitz T, Li D, et al. Temporal lobe involvement in multiple sclerosis patients with psychiatric disorders. Arch Neurol 1987;44:187-90.

13. Feinstein A, du Boulay G, Ron M. Psychotic illness in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry 1992;161:680-5.

14. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:27-33.

15. Drake ME. Acute paranoid psychosis in multiple sclerosis. Psychosomatics 1984;25:60-3.

16. Chong SA, Ko SM. Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:90-1.

17. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004;28:743-4.

18. Asghar-Ali A, Taber K, Hurley R, Hayman L. Pure neuropsychiatric presentation of multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:226-31.

1. Kaplan B, Sadock V, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:1107,1299.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Howard R, Rabins P, Seeman M, Jeste D. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172-8.

4. Lautenschlager NT, Forstl H. Organic psychosis: insight into the biology of psychosis. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2001;3:319-25.

5. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121-7.

6. Pine D, Douglas C, Charles E, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis presenting to psychiatric hospitals. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:297-306.

7. Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, Renshaw PF. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996;8:54-9.

8. Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Cummings JL, Velazquez J, Garcia de la Cadena C. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999;11:51-7.

9. Felgenhauer K. Psychiatric disorders in the encephalitic form of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 1990;237:11-8.

10. Skegg K, Corwin P, Skegg D. How often is multiple sclerosis mistaken for a psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med 1988;18:733-6.

11. Kohler J, Heilmeyer H, Volk B. Multiple sclerosis presenting as chronic atypical psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988;51:281-4.

12. Honer G, Hurwitz T, Li D, et al. Temporal lobe involvement in multiple sclerosis patients with psychiatric disorders. Arch Neurol 1987;44:187-90.

13. Feinstein A, du Boulay G, Ron M. Psychotic illness in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Br J Psychiatry 1992;161:680-5.

14. Sirois F. Steroid psychosis: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:27-33.

15. Drake ME. Acute paranoid psychosis in multiple sclerosis. Psychosomatics 1984;25:60-3.

16. Chong SA, Ko SM. Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:90-1.

17. Davids E, Hartwig U, Gastpar M. Antipsychotic treatment of psychosis associated with multiple sclerosis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004;28:743-4.

18. Asghar-Ali A, Taber K, Hurley R, Hayman L. Pure neuropsychiatric presentation of multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:226-31.