User login

One of the most common reasons medical colleagues seek consultation with a psychiatrist is to address the question of capacity. Indeed, this referral question often is posed as, “Is the patient competent?”

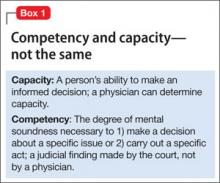

This referral question is incomplete and incorrectly phrased. The question should include the domain in which capacity is being questioned—for example, “Is the patient competent to refuse surgery?” Specifically identifying the area in which competency is questioned is necessary because a person might be competent in one area and incompetent in another (Box 1).

The question of competency should be modified as follows: “Does the patient have capacity to refuse surgery?” Competency is the degree of mental soundness necessary to make decisions about a specific issue or to carry out a specific act. Capacity is a person’s ability to make an informed decision. A determination of competency is a judicial finding made by the court. A physician can opine about a patient’s capacity, but cannot determine competency.

Adults are presumed to have capacity unless determined otherwise by the court. A person who lacks capacity to make an informed decision or give consent might need to be referred for a competency hearing or have a guardian appointed. Psychiatrists often are called on to provide an opinion to the court regarding a person’s capacity. Psychiatrists are particularly skilled at accessing a person’s mental status and gauging its potential for interfering with specific areas of functioning, but, in fact, any physician can make a determination of capacity.1

In this article, I:

- outline the components of a capacity evaluation

- describe the tools used in the determination of capacity

- review the typical features of patients and psychiatrists who perform capacity evaluations.

What constitutes a capacity evaluation?

The components of a capacity evaluation are comprehension, free choice, and reliability.

Comprehension refers to a patient’s factual understanding of his (her) medical condition—for example, including the risks and benefits of treatment and reasonable alternatives. The patient should show an understanding of 1) the situation as it relates to his condition, and 2) the consequences of his decisions. He also should demonstrate a rational manipulation of the information presented, applying a coherent and logical thought process to analyze possible courses of action.2

To determine if the patient has the requisite knowledge regarding his condition, the physician must be familiar with the patient’s clinical status. This might require consultation with the treating physician. Communication is a key component of capacity evaluations. Barriers to good communication can lead to the evaluating physician’s perception that the patient lacks capacity. If a patient does not understand his condition or the proposed treatments, the psychiatrist should educate him. It might be useful to arrange a meeting with the treating physician to facilitate communication.

Free choice. The patient’s decision to accept or reject a proposed treatment should be voluntary and free of coercion. In assessing a patient’s capacity, the psychiatrist should determine whether choices have been rendered impossible because of unrealistic fears or expectations about treatment, or because of impaired mental processes.

Reliability refers to a patient’s ability to provide a consistent choice over time. A patient who vacillates or is inconsistent does not have capacity to make decisions.

Features of patients referred for evaluation, and their evaluators

The most common reason for a capacity evaluation is a patient’s refusal of medical treatment. Between 3% and 25% of requests for psychiatric consultation in hospital settings involve questions about patients’ competence to make a treatment-related decision.3 Approximately 25% of adult medicine inpatients lack capacity for medical decision-making.4

Decision-making capacity is a functional evaluation. Decision-making capacity does not relate specifically to a person’s psychiatric diagnosis. In other words, the presence of a mental disorder does not render a person incapable of making decisions. However, people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia have a high rate of impaired capacity for making treatment decisions.

Schizophrenia has been found to have the highest rate of impaired decision-making among psychiatric disorders; depression is second and bipolar disorder, third. The strongest predictor of incapacity in psychiatric patients is lack of insight.5 Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, severity of symptoms, involuntary admission, lack of insight, and treatment refusal were strong predictors of incapacity in a sample of psychiatric patients.6

The neuronal basis of decision-making is unknown. Studies have implicated functioning of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortex as an important correlate of decision-making capacity.7 As a result of these findings, a brain-based criterion could be added to the conceptual criteria of capacity. The specific neuropsychological components necessary for decision-making capacity are unknown. Some studies suggest that poor executive functioning and limited learning ability correlate with impaired decision-making capacity.8 Little is known about the relationship between emotion and capacity. Supady et al demonstrated that higher cognitive empathy and good emotion recognition were associated with increased decision-making capacity and higher rates of refusal to give informed consent.9

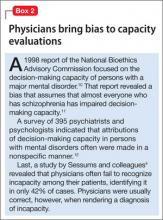

Physician bias has been identified in capacity evaluations. See Box 2.4,10-12

Tools used in capacity evaluations

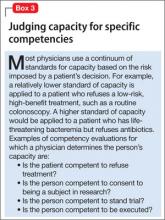

Most capacity evaluations are conducted by clinical interview (Box 3). The reliability of physicians’ unstructured judgments of capacity has been poor.13 In a study of 5 physicians who made a determination of capacity after watching a videotape of capacity assessments, the rate of agreement among the subjects was no better than that of chance.14

There is no specific, simple, quick test to assess capacity.

Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination. The MMSE has not been found to be predictive of decision-making capacity. It has been found to correlate with clinical judgments of incapacity, and may be used to identify patients at the high and low ends of the range of capacity, especially among older persons who exhibit cognitive impairment.15 Patients who have severe dementia (MMSE score <16) have a high likelihood of being unable to consent to treatment.16

MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool-Treatment. The MacCAT-T is a structured interviewing tool used to evaluate a patient’s decision-making ability. It is the most commonly used screening tool to evaluate decision-making capacity. Advantages of the MacCAT-T include a higher inter-rater agreement and—unlike other assessment instruments—its ability to incorporate information specific to a patient’s decision-making situation.17 The MacCAT-T requires training and experience to administer.

Bottom Line

Physicians make decisions about a patient’s decision-making capacity. Courts determine competence by a formal judicial proceeding. The psychiatric consultant’s role in capacity evaluations is to determine if the patient 1) possesses the requisite knowledge about the specific referral issue and 2) demonstrates a voluntary and reliable decision.

Related Resources

- The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. www.macarthur.virginia.edu/treatment.html.

- Resnick P, Sorrentino R: Forensic considerations (chapter. 8). In: Psychosomatic medicine. Blumenfield M, Strain JJ, eds. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:91-106.

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Disclosure

Dr. Sorrentino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Grisson T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment—a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen LM, McCue JD, Green GM. Do clinical and formal assessments of capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21): 2841-2845.

3. Farnsworth MG. Competency evaluations in a general hospital. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):60-66.

4. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011; 306(4):420-427.

5. Cairns R, Maddock C, Buchanan A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of mental incapacity in psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:379-385.

6. Candia PC, Barba AC. Mental capacity and consent to treatment in psychiatric patients: the state of the research. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(5):442-446.

7. Duncan J. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(10):475-483.

8. Mandarelli G, Parmigiani G, Tarsitani L, et al. The relationship between executive functions and capacity to consent to treatment in acute psychiatric hospitalization. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(5):63-70.

9. Supady A, Voelkel A, Witzel J, et al. How is informed consent related to emotions and empathy? An exploratory neuroethical investigation. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(5):311-317.

10. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):121-128.

11. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD. Challenges for designing and implementing decision aids. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54(3):265-273.

12. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692.

13. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(18):1834-1840.

14. Marson DC, McIntruff B, Hawkins L, et al. Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent to mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(4):453-457.

15. Kim SY, Caine ED. Utility and limits of the mini mental status examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(10):1322-1324.

16. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

17. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur competence assessment tool for treatment (MacCAT-T). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1998.

One of the most common reasons medical colleagues seek consultation with a psychiatrist is to address the question of capacity. Indeed, this referral question often is posed as, “Is the patient competent?”

This referral question is incomplete and incorrectly phrased. The question should include the domain in which capacity is being questioned—for example, “Is the patient competent to refuse surgery?” Specifically identifying the area in which competency is questioned is necessary because a person might be competent in one area and incompetent in another (Box 1).

The question of competency should be modified as follows: “Does the patient have capacity to refuse surgery?” Competency is the degree of mental soundness necessary to make decisions about a specific issue or to carry out a specific act. Capacity is a person’s ability to make an informed decision. A determination of competency is a judicial finding made by the court. A physician can opine about a patient’s capacity, but cannot determine competency.

Adults are presumed to have capacity unless determined otherwise by the court. A person who lacks capacity to make an informed decision or give consent might need to be referred for a competency hearing or have a guardian appointed. Psychiatrists often are called on to provide an opinion to the court regarding a person’s capacity. Psychiatrists are particularly skilled at accessing a person’s mental status and gauging its potential for interfering with specific areas of functioning, but, in fact, any physician can make a determination of capacity.1

In this article, I:

- outline the components of a capacity evaluation

- describe the tools used in the determination of capacity

- review the typical features of patients and psychiatrists who perform capacity evaluations.

What constitutes a capacity evaluation?

The components of a capacity evaluation are comprehension, free choice, and reliability.

Comprehension refers to a patient’s factual understanding of his (her) medical condition—for example, including the risks and benefits of treatment and reasonable alternatives. The patient should show an understanding of 1) the situation as it relates to his condition, and 2) the consequences of his decisions. He also should demonstrate a rational manipulation of the information presented, applying a coherent and logical thought process to analyze possible courses of action.2

To determine if the patient has the requisite knowledge regarding his condition, the physician must be familiar with the patient’s clinical status. This might require consultation with the treating physician. Communication is a key component of capacity evaluations. Barriers to good communication can lead to the evaluating physician’s perception that the patient lacks capacity. If a patient does not understand his condition or the proposed treatments, the psychiatrist should educate him. It might be useful to arrange a meeting with the treating physician to facilitate communication.

Free choice. The patient’s decision to accept or reject a proposed treatment should be voluntary and free of coercion. In assessing a patient’s capacity, the psychiatrist should determine whether choices have been rendered impossible because of unrealistic fears or expectations about treatment, or because of impaired mental processes.

Reliability refers to a patient’s ability to provide a consistent choice over time. A patient who vacillates or is inconsistent does not have capacity to make decisions.

Features of patients referred for evaluation, and their evaluators

The most common reason for a capacity evaluation is a patient’s refusal of medical treatment. Between 3% and 25% of requests for psychiatric consultation in hospital settings involve questions about patients’ competence to make a treatment-related decision.3 Approximately 25% of adult medicine inpatients lack capacity for medical decision-making.4

Decision-making capacity is a functional evaluation. Decision-making capacity does not relate specifically to a person’s psychiatric diagnosis. In other words, the presence of a mental disorder does not render a person incapable of making decisions. However, people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia have a high rate of impaired capacity for making treatment decisions.

Schizophrenia has been found to have the highest rate of impaired decision-making among psychiatric disorders; depression is second and bipolar disorder, third. The strongest predictor of incapacity in psychiatric patients is lack of insight.5 Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, severity of symptoms, involuntary admission, lack of insight, and treatment refusal were strong predictors of incapacity in a sample of psychiatric patients.6

The neuronal basis of decision-making is unknown. Studies have implicated functioning of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortex as an important correlate of decision-making capacity.7 As a result of these findings, a brain-based criterion could be added to the conceptual criteria of capacity. The specific neuropsychological components necessary for decision-making capacity are unknown. Some studies suggest that poor executive functioning and limited learning ability correlate with impaired decision-making capacity.8 Little is known about the relationship between emotion and capacity. Supady et al demonstrated that higher cognitive empathy and good emotion recognition were associated with increased decision-making capacity and higher rates of refusal to give informed consent.9

Physician bias has been identified in capacity evaluations. See Box 2.4,10-12

Tools used in capacity evaluations

Most capacity evaluations are conducted by clinical interview (Box 3). The reliability of physicians’ unstructured judgments of capacity has been poor.13 In a study of 5 physicians who made a determination of capacity after watching a videotape of capacity assessments, the rate of agreement among the subjects was no better than that of chance.14

There is no specific, simple, quick test to assess capacity.

Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination. The MMSE has not been found to be predictive of decision-making capacity. It has been found to correlate with clinical judgments of incapacity, and may be used to identify patients at the high and low ends of the range of capacity, especially among older persons who exhibit cognitive impairment.15 Patients who have severe dementia (MMSE score <16) have a high likelihood of being unable to consent to treatment.16

MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool-Treatment. The MacCAT-T is a structured interviewing tool used to evaluate a patient’s decision-making ability. It is the most commonly used screening tool to evaluate decision-making capacity. Advantages of the MacCAT-T include a higher inter-rater agreement and—unlike other assessment instruments—its ability to incorporate information specific to a patient’s decision-making situation.17 The MacCAT-T requires training and experience to administer.

Bottom Line

Physicians make decisions about a patient’s decision-making capacity. Courts determine competence by a formal judicial proceeding. The psychiatric consultant’s role in capacity evaluations is to determine if the patient 1) possesses the requisite knowledge about the specific referral issue and 2) demonstrates a voluntary and reliable decision.

Related Resources

- The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. www.macarthur.virginia.edu/treatment.html.

- Resnick P, Sorrentino R: Forensic considerations (chapter. 8). In: Psychosomatic medicine. Blumenfield M, Strain JJ, eds. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:91-106.

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Disclosure

Dr. Sorrentino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

One of the most common reasons medical colleagues seek consultation with a psychiatrist is to address the question of capacity. Indeed, this referral question often is posed as, “Is the patient competent?”

This referral question is incomplete and incorrectly phrased. The question should include the domain in which capacity is being questioned—for example, “Is the patient competent to refuse surgery?” Specifically identifying the area in which competency is questioned is necessary because a person might be competent in one area and incompetent in another (Box 1).

The question of competency should be modified as follows: “Does the patient have capacity to refuse surgery?” Competency is the degree of mental soundness necessary to make decisions about a specific issue or to carry out a specific act. Capacity is a person’s ability to make an informed decision. A determination of competency is a judicial finding made by the court. A physician can opine about a patient’s capacity, but cannot determine competency.

Adults are presumed to have capacity unless determined otherwise by the court. A person who lacks capacity to make an informed decision or give consent might need to be referred for a competency hearing or have a guardian appointed. Psychiatrists often are called on to provide an opinion to the court regarding a person’s capacity. Psychiatrists are particularly skilled at accessing a person’s mental status and gauging its potential for interfering with specific areas of functioning, but, in fact, any physician can make a determination of capacity.1

In this article, I:

- outline the components of a capacity evaluation

- describe the tools used in the determination of capacity

- review the typical features of patients and psychiatrists who perform capacity evaluations.

What constitutes a capacity evaluation?

The components of a capacity evaluation are comprehension, free choice, and reliability.

Comprehension refers to a patient’s factual understanding of his (her) medical condition—for example, including the risks and benefits of treatment and reasonable alternatives. The patient should show an understanding of 1) the situation as it relates to his condition, and 2) the consequences of his decisions. He also should demonstrate a rational manipulation of the information presented, applying a coherent and logical thought process to analyze possible courses of action.2

To determine if the patient has the requisite knowledge regarding his condition, the physician must be familiar with the patient’s clinical status. This might require consultation with the treating physician. Communication is a key component of capacity evaluations. Barriers to good communication can lead to the evaluating physician’s perception that the patient lacks capacity. If a patient does not understand his condition or the proposed treatments, the psychiatrist should educate him. It might be useful to arrange a meeting with the treating physician to facilitate communication.

Free choice. The patient’s decision to accept or reject a proposed treatment should be voluntary and free of coercion. In assessing a patient’s capacity, the psychiatrist should determine whether choices have been rendered impossible because of unrealistic fears or expectations about treatment, or because of impaired mental processes.

Reliability refers to a patient’s ability to provide a consistent choice over time. A patient who vacillates or is inconsistent does not have capacity to make decisions.

Features of patients referred for evaluation, and their evaluators

The most common reason for a capacity evaluation is a patient’s refusal of medical treatment. Between 3% and 25% of requests for psychiatric consultation in hospital settings involve questions about patients’ competence to make a treatment-related decision.3 Approximately 25% of adult medicine inpatients lack capacity for medical decision-making.4

Decision-making capacity is a functional evaluation. Decision-making capacity does not relate specifically to a person’s psychiatric diagnosis. In other words, the presence of a mental disorder does not render a person incapable of making decisions. However, people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia have a high rate of impaired capacity for making treatment decisions.

Schizophrenia has been found to have the highest rate of impaired decision-making among psychiatric disorders; depression is second and bipolar disorder, third. The strongest predictor of incapacity in psychiatric patients is lack of insight.5 Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, severity of symptoms, involuntary admission, lack of insight, and treatment refusal were strong predictors of incapacity in a sample of psychiatric patients.6

The neuronal basis of decision-making is unknown. Studies have implicated functioning of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortex as an important correlate of decision-making capacity.7 As a result of these findings, a brain-based criterion could be added to the conceptual criteria of capacity. The specific neuropsychological components necessary for decision-making capacity are unknown. Some studies suggest that poor executive functioning and limited learning ability correlate with impaired decision-making capacity.8 Little is known about the relationship between emotion and capacity. Supady et al demonstrated that higher cognitive empathy and good emotion recognition were associated with increased decision-making capacity and higher rates of refusal to give informed consent.9

Physician bias has been identified in capacity evaluations. See Box 2.4,10-12

Tools used in capacity evaluations

Most capacity evaluations are conducted by clinical interview (Box 3). The reliability of physicians’ unstructured judgments of capacity has been poor.13 In a study of 5 physicians who made a determination of capacity after watching a videotape of capacity assessments, the rate of agreement among the subjects was no better than that of chance.14

There is no specific, simple, quick test to assess capacity.

Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination. The MMSE has not been found to be predictive of decision-making capacity. It has been found to correlate with clinical judgments of incapacity, and may be used to identify patients at the high and low ends of the range of capacity, especially among older persons who exhibit cognitive impairment.15 Patients who have severe dementia (MMSE score <16) have a high likelihood of being unable to consent to treatment.16

MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool-Treatment. The MacCAT-T is a structured interviewing tool used to evaluate a patient’s decision-making ability. It is the most commonly used screening tool to evaluate decision-making capacity. Advantages of the MacCAT-T include a higher inter-rater agreement and—unlike other assessment instruments—its ability to incorporate information specific to a patient’s decision-making situation.17 The MacCAT-T requires training and experience to administer.

Bottom Line

Physicians make decisions about a patient’s decision-making capacity. Courts determine competence by a formal judicial proceeding. The psychiatric consultant’s role in capacity evaluations is to determine if the patient 1) possesses the requisite knowledge about the specific referral issue and 2) demonstrates a voluntary and reliable decision.

Related Resources

- The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. www.macarthur.virginia.edu/treatment.html.

- Resnick P, Sorrentino R: Forensic considerations (chapter. 8). In: Psychosomatic medicine. Blumenfield M, Strain JJ, eds. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:91-106.

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Disclosure

Dr. Sorrentino reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Grisson T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment—a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen LM, McCue JD, Green GM. Do clinical and formal assessments of capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21): 2841-2845.

3. Farnsworth MG. Competency evaluations in a general hospital. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):60-66.

4. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011; 306(4):420-427.

5. Cairns R, Maddock C, Buchanan A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of mental incapacity in psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:379-385.

6. Candia PC, Barba AC. Mental capacity and consent to treatment in psychiatric patients: the state of the research. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(5):442-446.

7. Duncan J. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(10):475-483.

8. Mandarelli G, Parmigiani G, Tarsitani L, et al. The relationship between executive functions and capacity to consent to treatment in acute psychiatric hospitalization. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(5):63-70.

9. Supady A, Voelkel A, Witzel J, et al. How is informed consent related to emotions and empathy? An exploratory neuroethical investigation. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(5):311-317.

10. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):121-128.

11. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD. Challenges for designing and implementing decision aids. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54(3):265-273.

12. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692.

13. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(18):1834-1840.

14. Marson DC, McIntruff B, Hawkins L, et al. Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent to mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(4):453-457.

15. Kim SY, Caine ED. Utility and limits of the mini mental status examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(10):1322-1324.

16. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

17. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur competence assessment tool for treatment (MacCAT-T). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1998.

1. Grisson T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment—a guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

2. Cohen LM, McCue JD, Green GM. Do clinical and formal assessments of capacity of patients in the intensive care unit to make decisions agree? Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21): 2841-2845.

3. Farnsworth MG. Competency evaluations in a general hospital. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):60-66.

4. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011; 306(4):420-427.

5. Cairns R, Maddock C, Buchanan A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of mental incapacity in psychiatric in-patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:379-385.

6. Candia PC, Barba AC. Mental capacity and consent to treatment in psychiatric patients: the state of the research. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(5):442-446.

7. Duncan J. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(10):475-483.

8. Mandarelli G, Parmigiani G, Tarsitani L, et al. The relationship between executive functions and capacity to consent to treatment in acute psychiatric hospitalization. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(5):63-70.

9. Supady A, Voelkel A, Witzel J, et al. How is informed consent related to emotions and empathy? An exploratory neuroethical investigation. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(5):311-317.

10. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):121-128.

11. Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD. Challenges for designing and implementing decision aids. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54(3):265-273.

12. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681-692.

13. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(18):1834-1840.

14. Marson DC, McIntruff B, Hawkins L, et al. Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent to mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(4):453-457.

15. Kim SY, Caine ED. Utility and limits of the mini mental status examination in evaluating consent capacity in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(10):1322-1324.

16. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

17. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur competence assessment tool for treatment (MacCAT-T). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 1998.