User login

The number of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) entering the adult health care system is increasing, a not-so-surprising trend when you consider that more than 80% of children and adolescents given a cancer diagnosis become long-term survivors.1 This patient population has a heightened risk for developing at least one chronic health problem, resulting from therapy. By the fourth decade of life, 88% of all CCSs will have a chronic condition,2 and about one-third develop a late effect that is either severe or life-threatening.3 In contrast to patients with many other pediatric chronic diseases that manifest at an early age and are progressive, CCSs are often physically well for many years, or decades, prior to their manifestation of late effects.4

Cancer survivorship has varying definitions; however, we define cancer survivorship as the phase of cancer care for individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer and have completed primary treatment for their disease.5 Cancer survivorship, which is becoming more widely acknowledged as a distinct and critically important phase of cancer care, includes:6

- “surveillance for recurrence,

- evaluation … and treatment of medical and psychosocial consequences of treatment,

- recommendations for screening for new primary cancers,

- health promotion recommendations, and

- provision of a written treatment summary and care plan to the patient and other health professionals.”

Although models of survivorship care vary, their common goal is to promote optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and to prevent and detect any health concerns that may be related to prior cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Some pediatric cancer survivors have not received recommended survivorship care because of a lack of insurance or limitations from pre-existing conditions.4,7 The Affordable Care Act may remove these barriers for many.8 Others, however, fail to receive such recommendations because national models of transition are lacking. Unique considerations for this population include their need to establish age appropriate, lifelong follow-up care (and education) from a primary care provider (PCP). Unfortunately, many CCSs become lost to follow-up and fail to receive recommended survivorship care when they discontinue the relationship with their pediatrician or family practitioner and their pediatric oncologist. Fewer than 25% of CCSs who have been successfully treated for cancer during childhood continue to be followed by a cancer center and are at risk for missing survivorship-focused care or recommended screening.4,9

PCPs are an invaluable link in helping CCSs to continue to receive recommended care and surveillance. However, PCPs experience barriers in providing cancer care because of a lack of timely and specific communication from oncologists and limited knowledge of guidelines and resources available to them.10 The purpose of this article is to share information with you, the family physician, about childhood cancer survivorship needs, available resources, and how partnering with pediatric oncologists may improve treatment and health outcomes for CCSs.

Providing for the future health of childhood cancer survivors

Numerous studies have outlined the myriad of potential late effects that CCSs may experience from disease and treatment.11,12 These effects can manifest at any time and can appear in virtually every body system from the central nervous system, to the lungs, heart, bones, and endocrine systems. CCSs' particular risk for late effects may result from many factors including cancer diagnosis, types of treatments (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem-cell transplant), and dosages of medications, gender, and age at diagnosis.

Determining individual risk for late effects

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) is the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research, including the long-term health of cancer survivors. To help provide more individualized recommendations, COG has set forth risk-based, evidence-based, exposure-related clinical practice guidelines to offer recommendations for screening and management of late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers.13 (These guidelines, Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, are available at http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org.) The purpose of the guidelines is to standardize and enhance follow-up care for CCSs throughout their lifespan.13 To remain current, a multidisciplinary task force reviews and incorporates findings from the medical literature—including evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of recommended testing—into guideline revisions at least every 5 years.

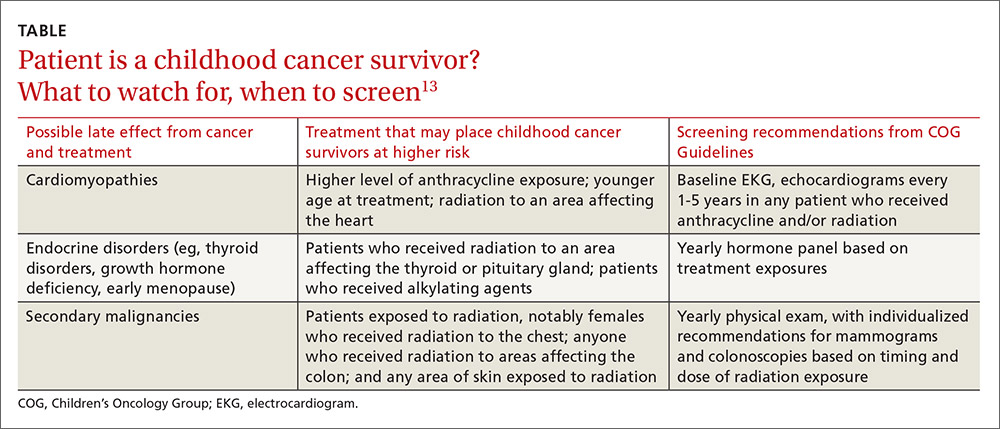

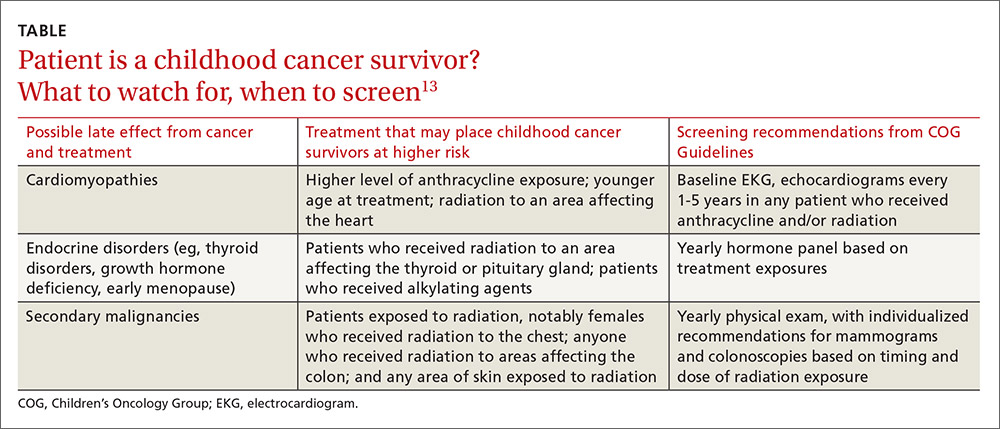

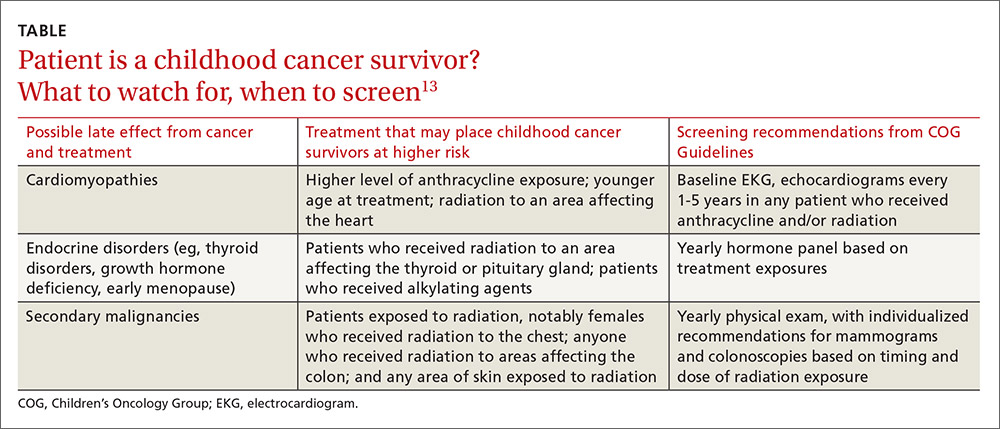

Some of the most severe or life-threatening late effects include cardiomyopathies, endocrine disorders, and secondary malignancies (TABLE).13 Ongoing follow-up care is based on a survivor’s individual risk level and the frequency of lifelong recommended screening. The majority of patients will require yearly follow-up with additional testing, such as echocardiograms occurring as infrequently as every 2 to 5 years. Patients who received more intense therapy, such as hematopoietic stem-cell transplants, will require follow-up (often including annual echocardiograms, blood work, and a thorough physical exam) every 6 months to one year. Common testing and surveillance include blood pressure checks, urinalyses, thyroid function tests, lipid panels, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms.

After treatment, patients should receive survivorship care plans

For health care providers to use COG Guidelines effectively across medical disciplines, it is important to know critical pieces of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment history. In 2006, the Institute of Medicine released a report14 recommending that all cancer survivors be given a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan when they complete their primary cancer care. More recently, the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons has mandated that, in order to be a cancer program accredited by the Commission, all cancer patients must be given a survivorship care plan after completing treatment.15 Generated by the treating cancer center, these care plans are meant to concisely communicate a patient’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and long-term risks to other health care providers (across disciplines and institutions).

What’s included in a survivorship care plan?

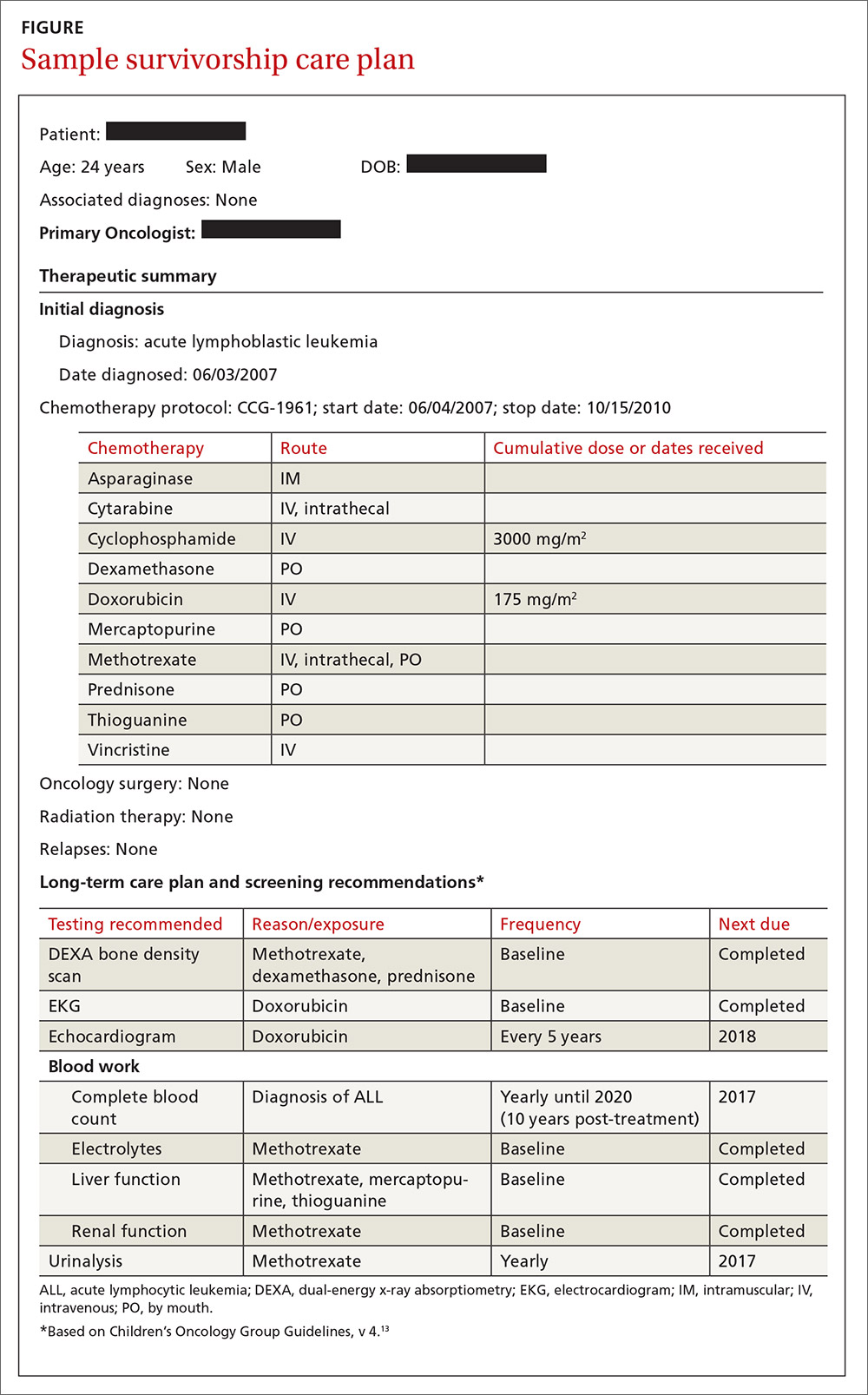

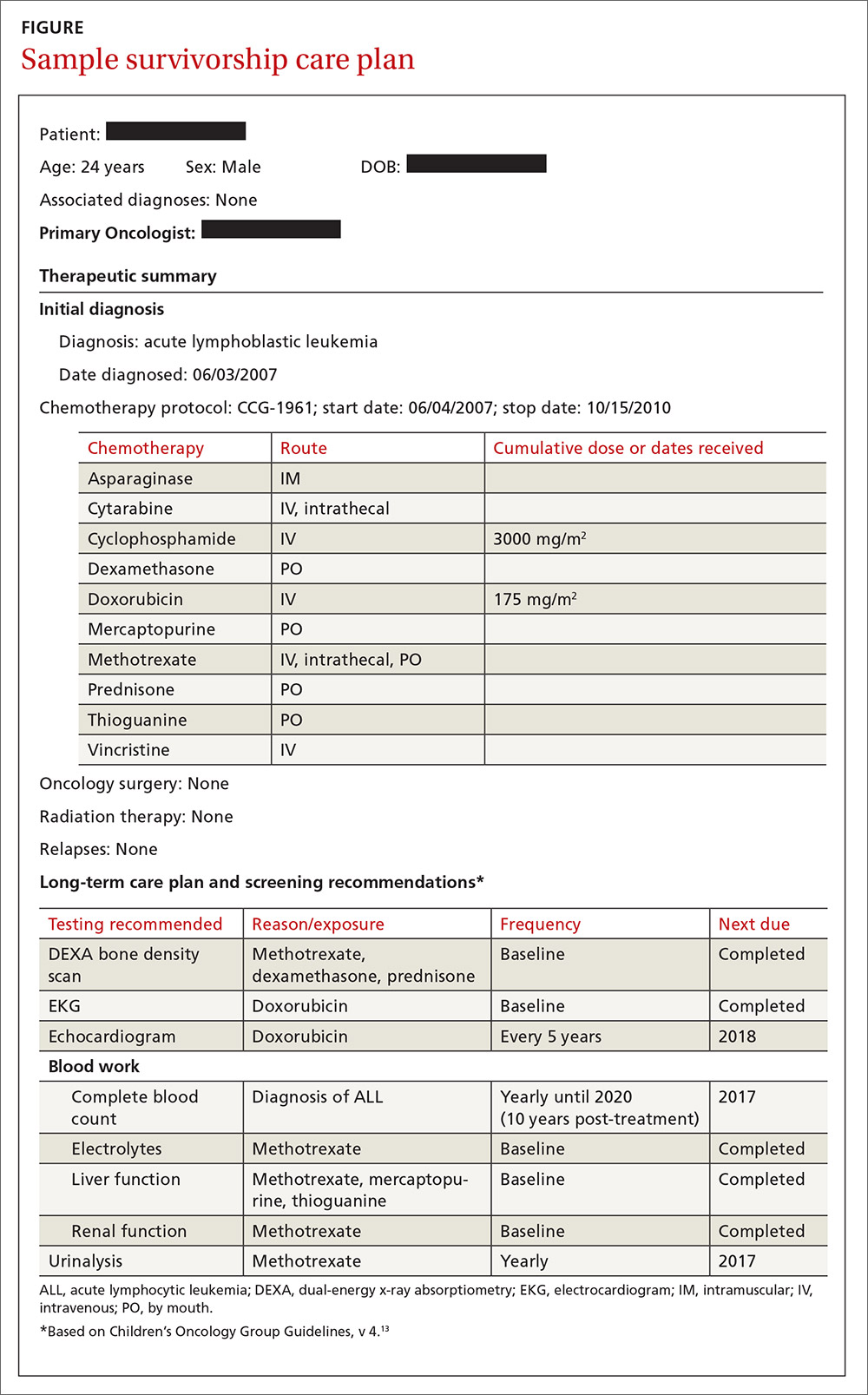

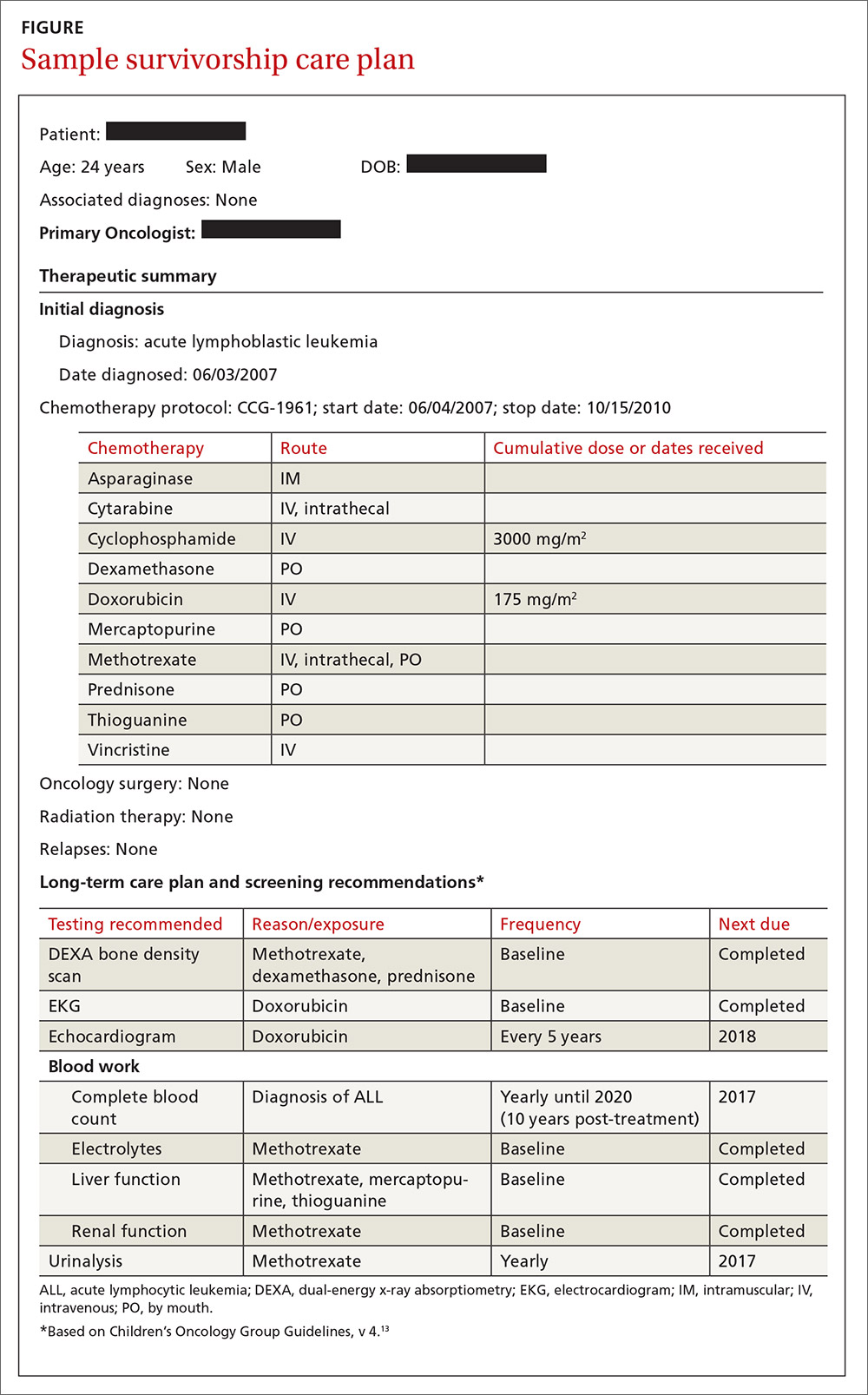

The survivorship care plan is a paper or electronic document created by the treating institution that contains 2 components: a treatment summary and a long-term care plan based on medical/treatment history. The treatment summary includes, at a minimum, general background information (eg, demographics, pertinent medical history, diagnostic details, and significant treatment complications) and a therapeutic summary (such as dates of treatment, protocol, and details of chemotherapy, radiation, hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, and/or surgery).

The second component, the long-term care plan, details potential long-term effects specific to the treatment received, and recommendations for ongoing follow-up related to long-term risk (FIGURE). The post-treatment plan is primarily based on COG Guideline recommendations. Many institutions are introducing an electronic-based survivorship care plan, either in addition to or in replacement of a paper-based care plan. Electronic-based care plans have several benefits for patients and providers, including increased accessibility, and some offer the ability to easily update follow-up recommendations, as guidelines change, without the need for manual entry.

Shared care for cancer survivors: Oncology and primary care

Numerous models of cancer survivorship care have been described, including care by the treating oncologist, a dedicated cancer survivorship program, or follow-up completed by PCPs. There is no consensus on the best model, although many have noted that shared care is a critically important component of successful cancer survivorship care,6,16–18 and appears to be the preferred model of PCPs.19

Shared care, as the name implies, involves care that is coordinated between 2 or more health providers across specialties or locations.20 This model has shown improved outcomes in other chronic disease-management models, such as those for diabetes21 and chronic renal disease.22 One study23 found that colorectal cancer survivors who were seen by both an oncologist and a PCP were significantly more likely to receive recommended testing and follow-up to promote overall health than when they were followed by either physician alone. Information sharing between oncology and PCPs is critical to maintaining and promoting optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and requires ongoing communication and a concerted effort to facilitate and maintain collaboration between oncology specialists and other health care providers.6,17

Role of the cancer center in survivorship care

Although every cancer center has a slightly different timeline and structure in terms of survivorship care, there are common themes across programs regarding the type of care provided. Immediately following treatment, care is focused on surveillance for recurrence, with appointments ranging from monthly to a few times a year. This care is most often provided by the primary oncologist.

The next phase of care is reached 2 to 5 years after treatment, when recurrence is no longer a significant risk, and care is focused on monitoring and treating late effects. Depending on the center, this care may be coordinated by a dedicated survivorship clinic, the primary oncologist, or the PCP. In some models,6 the survivorship team is integrated into the patient’s care from the beginning of treatment, while others do not become active in care until the patient is considered cured of disease. In all models, a survivorship care plan should be completed after treatment has ended and before transitioning care to a PCP.

In our institution’s model, we have a survivorship program that serves patients who are more than 5 years from the completion of their treatment. Our survivorship team is comprised of a pediatric oncologist, advanced practice practitioner (APP) coordinator, a project coordinator, a clinical social worker, and a research staff member. Patients are seen every one to 2 years, depending on their overall risk for late effects. For those who are seen every other year, we are available to the PCP for questions or concerns, and the survivorship team connects with the CCS by phone to screen for any change in health status that would alter recommendations for an earlier follow-up at the oncology center.

A typical visit to our survivorship clinic includes completion of an annual health questionnaire, which addresses current health issues, as well as screening for anxiety, depression, nicotine, alcohol, and drug use. This questionnaire is reviewed by the pediatric oncologist and is used to tailor screening, referrals, and patient education based on current complaints. The oncologist also performs a thorough physical exam with special attention to areas in which late effects may occur (eg, skin exam in areas of previous radiation). In addition, each patient receives an individualized treatment summary based on COG guidelines, which is updated before each visit by the APP coordinator. The APP coordinator reviews the document at each visit and offers patient education and health maintenance counseling.

Ensuring patients aren’t lost to follow-up. In our experience, numerous patients become lost to follow-up as they age, enter college or the workforce, or move away. So, rather than attempting to follow these patients for life, we work to transition patient care to a PCP of their choice, particularly if they are at least 21 years old and more than 10 years post-diagnosis. However, we will work to transition at any time at the request of the CCS. Even when a patient’s ongoing care is transitioned to a PCP, we will remain as a continuing resource to PCPs and CCSs on an as-needed basis.

Role of primary care providers in survivorship care

Every health care provider caring for a CCS should have a copy of the patient’s survivorship care plan. This document should be provided by the treating institution, but research has shown that as many as 86% of PCPs fail to receive this critical information.24 Any PCP who treats a patient with a history of cancer and has not received a survivorship care plan should contact the treating cancer center to request a copy. A properly prepared survivorship care plan summarizes the patient’s disease and treatment history, and provides a road map of the patient’s risk for long-term effects from disease and treatment.

The most important sections of the survivorship care plan for use in primary care will be the list of potential late effects and ongoing recommended testing. This list will help to guide the PCP’s differential and work-up for specific complaints. For example, knowing that a patient is at risk for a second malignancy because of radiation therapy may result in earlier diagnostic imaging, leading to a timelier diagnosis.

The COG screening recommendations that are generally included in a survivorship care plan are appropriate for survivors who are asymptomatic and presenting for routine, exposure-based medical follow-up. More extensive work-ups are presumed to be completed as clinically indicated. Consultation with a pediatric long-term follow-up clinic is also encouraged, particularly if a concern arises.

A complementary set of patient education materials, known as “Health Links,” accompany the COG guidelines to broaden their application and enhance patient follow-up visits. A survivorship care plan and the COG Guidelines help ensure that CCSs receive appropriate ongoing follow-up based on their history. A collaborative approach between Oncology and PCPs is essential to improve the quality of care for CCSs and to maintain the long-term health of this vulnerable population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jean M. Tersak, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, 4401 Penn Avenue, 5th Floor Plaza Building, Pittsburgh, PA 15224; [email protected].

1. Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2002. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:653-663.

3. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572-1582.

4. Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4401-4409.

5. Feuerstein M. Defining cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:5-7.

6. McCabe MS, Jacobs LA. Clinical update: survivorship care—models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:e1-e8.

7. Oeffinger K, Mertens A, Hudson M, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61-70.

8. Mueller EL, Park ER, Davis MM. What the affordable care act means for survivors of pediatric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:615-617.

9. Oeffinger KC. Longitudinal risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2003;27:143-167.

10. Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CE, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016:1-15.

11. Schwartz CL. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the late effects of therapy. Oncologist. 1999;4:45-54.

12. Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated March 31, 2016. Available at: www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-hp-pdq. Accessed June 2, 2016.

13. Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer, Version 4.0. Monrovia CA: Children’s Oncology Group. 2013. Available at: www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed June 2, 2016.

14. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council, eds. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

15. Commission on Cancer [Internet]. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2015. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed June 2, 2016.

16. Askins MA, Moore BD. Preventing neurocognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1160-1171.

17. McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202-207.

18. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117-5124.

19. Potosky AL, Han PKJ, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

20. Gilbert SM, Miller DC, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Cancer survivorship: challenges and changing paradigms. J Urol. 2008;179:431-438.

21. Renders CM, Valk GD, de Sonnaville JJ, et al. Quality of care for patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus—a long-term comparison of two quality improvement programmes in the Netherlands. Diabet Med. 2003;20:846-852.

22. Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, et al. An evaluation of a shared primary and secondary care nephrology service for managing patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:103-114.

23. Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712-1719.

24. Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:118-124.

The number of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) entering the adult health care system is increasing, a not-so-surprising trend when you consider that more than 80% of children and adolescents given a cancer diagnosis become long-term survivors.1 This patient population has a heightened risk for developing at least one chronic health problem, resulting from therapy. By the fourth decade of life, 88% of all CCSs will have a chronic condition,2 and about one-third develop a late effect that is either severe or life-threatening.3 In contrast to patients with many other pediatric chronic diseases that manifest at an early age and are progressive, CCSs are often physically well for many years, or decades, prior to their manifestation of late effects.4

Cancer survivorship has varying definitions; however, we define cancer survivorship as the phase of cancer care for individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer and have completed primary treatment for their disease.5 Cancer survivorship, which is becoming more widely acknowledged as a distinct and critically important phase of cancer care, includes:6

- “surveillance for recurrence,

- evaluation … and treatment of medical and psychosocial consequences of treatment,

- recommendations for screening for new primary cancers,

- health promotion recommendations, and

- provision of a written treatment summary and care plan to the patient and other health professionals.”

Although models of survivorship care vary, their common goal is to promote optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and to prevent and detect any health concerns that may be related to prior cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Some pediatric cancer survivors have not received recommended survivorship care because of a lack of insurance or limitations from pre-existing conditions.4,7 The Affordable Care Act may remove these barriers for many.8 Others, however, fail to receive such recommendations because national models of transition are lacking. Unique considerations for this population include their need to establish age appropriate, lifelong follow-up care (and education) from a primary care provider (PCP). Unfortunately, many CCSs become lost to follow-up and fail to receive recommended survivorship care when they discontinue the relationship with their pediatrician or family practitioner and their pediatric oncologist. Fewer than 25% of CCSs who have been successfully treated for cancer during childhood continue to be followed by a cancer center and are at risk for missing survivorship-focused care or recommended screening.4,9

PCPs are an invaluable link in helping CCSs to continue to receive recommended care and surveillance. However, PCPs experience barriers in providing cancer care because of a lack of timely and specific communication from oncologists and limited knowledge of guidelines and resources available to them.10 The purpose of this article is to share information with you, the family physician, about childhood cancer survivorship needs, available resources, and how partnering with pediatric oncologists may improve treatment and health outcomes for CCSs.

Providing for the future health of childhood cancer survivors

Numerous studies have outlined the myriad of potential late effects that CCSs may experience from disease and treatment.11,12 These effects can manifest at any time and can appear in virtually every body system from the central nervous system, to the lungs, heart, bones, and endocrine systems. CCSs' particular risk for late effects may result from many factors including cancer diagnosis, types of treatments (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem-cell transplant), and dosages of medications, gender, and age at diagnosis.

Determining individual risk for late effects

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) is the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research, including the long-term health of cancer survivors. To help provide more individualized recommendations, COG has set forth risk-based, evidence-based, exposure-related clinical practice guidelines to offer recommendations for screening and management of late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers.13 (These guidelines, Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, are available at http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org.) The purpose of the guidelines is to standardize and enhance follow-up care for CCSs throughout their lifespan.13 To remain current, a multidisciplinary task force reviews and incorporates findings from the medical literature—including evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of recommended testing—into guideline revisions at least every 5 years.

Some of the most severe or life-threatening late effects include cardiomyopathies, endocrine disorders, and secondary malignancies (TABLE).13 Ongoing follow-up care is based on a survivor’s individual risk level and the frequency of lifelong recommended screening. The majority of patients will require yearly follow-up with additional testing, such as echocardiograms occurring as infrequently as every 2 to 5 years. Patients who received more intense therapy, such as hematopoietic stem-cell transplants, will require follow-up (often including annual echocardiograms, blood work, and a thorough physical exam) every 6 months to one year. Common testing and surveillance include blood pressure checks, urinalyses, thyroid function tests, lipid panels, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms.

After treatment, patients should receive survivorship care plans

For health care providers to use COG Guidelines effectively across medical disciplines, it is important to know critical pieces of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment history. In 2006, the Institute of Medicine released a report14 recommending that all cancer survivors be given a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan when they complete their primary cancer care. More recently, the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons has mandated that, in order to be a cancer program accredited by the Commission, all cancer patients must be given a survivorship care plan after completing treatment.15 Generated by the treating cancer center, these care plans are meant to concisely communicate a patient’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and long-term risks to other health care providers (across disciplines and institutions).

What’s included in a survivorship care plan?

The survivorship care plan is a paper or electronic document created by the treating institution that contains 2 components: a treatment summary and a long-term care plan based on medical/treatment history. The treatment summary includes, at a minimum, general background information (eg, demographics, pertinent medical history, diagnostic details, and significant treatment complications) and a therapeutic summary (such as dates of treatment, protocol, and details of chemotherapy, radiation, hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, and/or surgery).

The second component, the long-term care plan, details potential long-term effects specific to the treatment received, and recommendations for ongoing follow-up related to long-term risk (FIGURE). The post-treatment plan is primarily based on COG Guideline recommendations. Many institutions are introducing an electronic-based survivorship care plan, either in addition to or in replacement of a paper-based care plan. Electronic-based care plans have several benefits for patients and providers, including increased accessibility, and some offer the ability to easily update follow-up recommendations, as guidelines change, without the need for manual entry.

Shared care for cancer survivors: Oncology and primary care

Numerous models of cancer survivorship care have been described, including care by the treating oncologist, a dedicated cancer survivorship program, or follow-up completed by PCPs. There is no consensus on the best model, although many have noted that shared care is a critically important component of successful cancer survivorship care,6,16–18 and appears to be the preferred model of PCPs.19

Shared care, as the name implies, involves care that is coordinated between 2 or more health providers across specialties or locations.20 This model has shown improved outcomes in other chronic disease-management models, such as those for diabetes21 and chronic renal disease.22 One study23 found that colorectal cancer survivors who were seen by both an oncologist and a PCP were significantly more likely to receive recommended testing and follow-up to promote overall health than when they were followed by either physician alone. Information sharing between oncology and PCPs is critical to maintaining and promoting optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and requires ongoing communication and a concerted effort to facilitate and maintain collaboration between oncology specialists and other health care providers.6,17

Role of the cancer center in survivorship care

Although every cancer center has a slightly different timeline and structure in terms of survivorship care, there are common themes across programs regarding the type of care provided. Immediately following treatment, care is focused on surveillance for recurrence, with appointments ranging from monthly to a few times a year. This care is most often provided by the primary oncologist.

The next phase of care is reached 2 to 5 years after treatment, when recurrence is no longer a significant risk, and care is focused on monitoring and treating late effects. Depending on the center, this care may be coordinated by a dedicated survivorship clinic, the primary oncologist, or the PCP. In some models,6 the survivorship team is integrated into the patient’s care from the beginning of treatment, while others do not become active in care until the patient is considered cured of disease. In all models, a survivorship care plan should be completed after treatment has ended and before transitioning care to a PCP.

In our institution’s model, we have a survivorship program that serves patients who are more than 5 years from the completion of their treatment. Our survivorship team is comprised of a pediatric oncologist, advanced practice practitioner (APP) coordinator, a project coordinator, a clinical social worker, and a research staff member. Patients are seen every one to 2 years, depending on their overall risk for late effects. For those who are seen every other year, we are available to the PCP for questions or concerns, and the survivorship team connects with the CCS by phone to screen for any change in health status that would alter recommendations for an earlier follow-up at the oncology center.

A typical visit to our survivorship clinic includes completion of an annual health questionnaire, which addresses current health issues, as well as screening for anxiety, depression, nicotine, alcohol, and drug use. This questionnaire is reviewed by the pediatric oncologist and is used to tailor screening, referrals, and patient education based on current complaints. The oncologist also performs a thorough physical exam with special attention to areas in which late effects may occur (eg, skin exam in areas of previous radiation). In addition, each patient receives an individualized treatment summary based on COG guidelines, which is updated before each visit by the APP coordinator. The APP coordinator reviews the document at each visit and offers patient education and health maintenance counseling.

Ensuring patients aren’t lost to follow-up. In our experience, numerous patients become lost to follow-up as they age, enter college or the workforce, or move away. So, rather than attempting to follow these patients for life, we work to transition patient care to a PCP of their choice, particularly if they are at least 21 years old and more than 10 years post-diagnosis. However, we will work to transition at any time at the request of the CCS. Even when a patient’s ongoing care is transitioned to a PCP, we will remain as a continuing resource to PCPs and CCSs on an as-needed basis.

Role of primary care providers in survivorship care

Every health care provider caring for a CCS should have a copy of the patient’s survivorship care plan. This document should be provided by the treating institution, but research has shown that as many as 86% of PCPs fail to receive this critical information.24 Any PCP who treats a patient with a history of cancer and has not received a survivorship care plan should contact the treating cancer center to request a copy. A properly prepared survivorship care plan summarizes the patient’s disease and treatment history, and provides a road map of the patient’s risk for long-term effects from disease and treatment.

The most important sections of the survivorship care plan for use in primary care will be the list of potential late effects and ongoing recommended testing. This list will help to guide the PCP’s differential and work-up for specific complaints. For example, knowing that a patient is at risk for a second malignancy because of radiation therapy may result in earlier diagnostic imaging, leading to a timelier diagnosis.

The COG screening recommendations that are generally included in a survivorship care plan are appropriate for survivors who are asymptomatic and presenting for routine, exposure-based medical follow-up. More extensive work-ups are presumed to be completed as clinically indicated. Consultation with a pediatric long-term follow-up clinic is also encouraged, particularly if a concern arises.

A complementary set of patient education materials, known as “Health Links,” accompany the COG guidelines to broaden their application and enhance patient follow-up visits. A survivorship care plan and the COG Guidelines help ensure that CCSs receive appropriate ongoing follow-up based on their history. A collaborative approach between Oncology and PCPs is essential to improve the quality of care for CCSs and to maintain the long-term health of this vulnerable population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jean M. Tersak, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, 4401 Penn Avenue, 5th Floor Plaza Building, Pittsburgh, PA 15224; [email protected].

The number of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) entering the adult health care system is increasing, a not-so-surprising trend when you consider that more than 80% of children and adolescents given a cancer diagnosis become long-term survivors.1 This patient population has a heightened risk for developing at least one chronic health problem, resulting from therapy. By the fourth decade of life, 88% of all CCSs will have a chronic condition,2 and about one-third develop a late effect that is either severe or life-threatening.3 In contrast to patients with many other pediatric chronic diseases that manifest at an early age and are progressive, CCSs are often physically well for many years, or decades, prior to their manifestation of late effects.4

Cancer survivorship has varying definitions; however, we define cancer survivorship as the phase of cancer care for individuals who have been diagnosed with cancer and have completed primary treatment for their disease.5 Cancer survivorship, which is becoming more widely acknowledged as a distinct and critically important phase of cancer care, includes:6

- “surveillance for recurrence,

- evaluation … and treatment of medical and psychosocial consequences of treatment,

- recommendations for screening for new primary cancers,

- health promotion recommendations, and

- provision of a written treatment summary and care plan to the patient and other health professionals.”

Although models of survivorship care vary, their common goal is to promote optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and to prevent and detect any health concerns that may be related to prior cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Some pediatric cancer survivors have not received recommended survivorship care because of a lack of insurance or limitations from pre-existing conditions.4,7 The Affordable Care Act may remove these barriers for many.8 Others, however, fail to receive such recommendations because national models of transition are lacking. Unique considerations for this population include their need to establish age appropriate, lifelong follow-up care (and education) from a primary care provider (PCP). Unfortunately, many CCSs become lost to follow-up and fail to receive recommended survivorship care when they discontinue the relationship with their pediatrician or family practitioner and their pediatric oncologist. Fewer than 25% of CCSs who have been successfully treated for cancer during childhood continue to be followed by a cancer center and are at risk for missing survivorship-focused care or recommended screening.4,9

PCPs are an invaluable link in helping CCSs to continue to receive recommended care and surveillance. However, PCPs experience barriers in providing cancer care because of a lack of timely and specific communication from oncologists and limited knowledge of guidelines and resources available to them.10 The purpose of this article is to share information with you, the family physician, about childhood cancer survivorship needs, available resources, and how partnering with pediatric oncologists may improve treatment and health outcomes for CCSs.

Providing for the future health of childhood cancer survivors

Numerous studies have outlined the myriad of potential late effects that CCSs may experience from disease and treatment.11,12 These effects can manifest at any time and can appear in virtually every body system from the central nervous system, to the lungs, heart, bones, and endocrine systems. CCSs' particular risk for late effects may result from many factors including cancer diagnosis, types of treatments (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem-cell transplant), and dosages of medications, gender, and age at diagnosis.

Determining individual risk for late effects

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) is the world’s largest organization devoted exclusively to childhood and adolescent cancer research, including the long-term health of cancer survivors. To help provide more individualized recommendations, COG has set forth risk-based, evidence-based, exposure-related clinical practice guidelines to offer recommendations for screening and management of late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers.13 (These guidelines, Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers, are available at http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org.) The purpose of the guidelines is to standardize and enhance follow-up care for CCSs throughout their lifespan.13 To remain current, a multidisciplinary task force reviews and incorporates findings from the medical literature—including evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of recommended testing—into guideline revisions at least every 5 years.

Some of the most severe or life-threatening late effects include cardiomyopathies, endocrine disorders, and secondary malignancies (TABLE).13 Ongoing follow-up care is based on a survivor’s individual risk level and the frequency of lifelong recommended screening. The majority of patients will require yearly follow-up with additional testing, such as echocardiograms occurring as infrequently as every 2 to 5 years. Patients who received more intense therapy, such as hematopoietic stem-cell transplants, will require follow-up (often including annual echocardiograms, blood work, and a thorough physical exam) every 6 months to one year. Common testing and surveillance include blood pressure checks, urinalyses, thyroid function tests, lipid panels, echocardiograms, and electrocardiograms.

After treatment, patients should receive survivorship care plans

For health care providers to use COG Guidelines effectively across medical disciplines, it is important to know critical pieces of the patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment history. In 2006, the Institute of Medicine released a report14 recommending that all cancer survivors be given a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan when they complete their primary cancer care. More recently, the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons has mandated that, in order to be a cancer program accredited by the Commission, all cancer patients must be given a survivorship care plan after completing treatment.15 Generated by the treating cancer center, these care plans are meant to concisely communicate a patient’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and long-term risks to other health care providers (across disciplines and institutions).

What’s included in a survivorship care plan?

The survivorship care plan is a paper or electronic document created by the treating institution that contains 2 components: a treatment summary and a long-term care plan based on medical/treatment history. The treatment summary includes, at a minimum, general background information (eg, demographics, pertinent medical history, diagnostic details, and significant treatment complications) and a therapeutic summary (such as dates of treatment, protocol, and details of chemotherapy, radiation, hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, and/or surgery).

The second component, the long-term care plan, details potential long-term effects specific to the treatment received, and recommendations for ongoing follow-up related to long-term risk (FIGURE). The post-treatment plan is primarily based on COG Guideline recommendations. Many institutions are introducing an electronic-based survivorship care plan, either in addition to or in replacement of a paper-based care plan. Electronic-based care plans have several benefits for patients and providers, including increased accessibility, and some offer the ability to easily update follow-up recommendations, as guidelines change, without the need for manual entry.

Shared care for cancer survivors: Oncology and primary care

Numerous models of cancer survivorship care have been described, including care by the treating oncologist, a dedicated cancer survivorship program, or follow-up completed by PCPs. There is no consensus on the best model, although many have noted that shared care is a critically important component of successful cancer survivorship care,6,16–18 and appears to be the preferred model of PCPs.19

Shared care, as the name implies, involves care that is coordinated between 2 or more health providers across specialties or locations.20 This model has shown improved outcomes in other chronic disease-management models, such as those for diabetes21 and chronic renal disease.22 One study23 found that colorectal cancer survivors who were seen by both an oncologist and a PCP were significantly more likely to receive recommended testing and follow-up to promote overall health than when they were followed by either physician alone. Information sharing between oncology and PCPs is critical to maintaining and promoting optimal health and well-being in cancer survivors, and requires ongoing communication and a concerted effort to facilitate and maintain collaboration between oncology specialists and other health care providers.6,17

Role of the cancer center in survivorship care

Although every cancer center has a slightly different timeline and structure in terms of survivorship care, there are common themes across programs regarding the type of care provided. Immediately following treatment, care is focused on surveillance for recurrence, with appointments ranging from monthly to a few times a year. This care is most often provided by the primary oncologist.

The next phase of care is reached 2 to 5 years after treatment, when recurrence is no longer a significant risk, and care is focused on monitoring and treating late effects. Depending on the center, this care may be coordinated by a dedicated survivorship clinic, the primary oncologist, or the PCP. In some models,6 the survivorship team is integrated into the patient’s care from the beginning of treatment, while others do not become active in care until the patient is considered cured of disease. In all models, a survivorship care plan should be completed after treatment has ended and before transitioning care to a PCP.

In our institution’s model, we have a survivorship program that serves patients who are more than 5 years from the completion of their treatment. Our survivorship team is comprised of a pediatric oncologist, advanced practice practitioner (APP) coordinator, a project coordinator, a clinical social worker, and a research staff member. Patients are seen every one to 2 years, depending on their overall risk for late effects. For those who are seen every other year, we are available to the PCP for questions or concerns, and the survivorship team connects with the CCS by phone to screen for any change in health status that would alter recommendations for an earlier follow-up at the oncology center.

A typical visit to our survivorship clinic includes completion of an annual health questionnaire, which addresses current health issues, as well as screening for anxiety, depression, nicotine, alcohol, and drug use. This questionnaire is reviewed by the pediatric oncologist and is used to tailor screening, referrals, and patient education based on current complaints. The oncologist also performs a thorough physical exam with special attention to areas in which late effects may occur (eg, skin exam in areas of previous radiation). In addition, each patient receives an individualized treatment summary based on COG guidelines, which is updated before each visit by the APP coordinator. The APP coordinator reviews the document at each visit and offers patient education and health maintenance counseling.

Ensuring patients aren’t lost to follow-up. In our experience, numerous patients become lost to follow-up as they age, enter college or the workforce, or move away. So, rather than attempting to follow these patients for life, we work to transition patient care to a PCP of their choice, particularly if they are at least 21 years old and more than 10 years post-diagnosis. However, we will work to transition at any time at the request of the CCS. Even when a patient’s ongoing care is transitioned to a PCP, we will remain as a continuing resource to PCPs and CCSs on an as-needed basis.

Role of primary care providers in survivorship care

Every health care provider caring for a CCS should have a copy of the patient’s survivorship care plan. This document should be provided by the treating institution, but research has shown that as many as 86% of PCPs fail to receive this critical information.24 Any PCP who treats a patient with a history of cancer and has not received a survivorship care plan should contact the treating cancer center to request a copy. A properly prepared survivorship care plan summarizes the patient’s disease and treatment history, and provides a road map of the patient’s risk for long-term effects from disease and treatment.

The most important sections of the survivorship care plan for use in primary care will be the list of potential late effects and ongoing recommended testing. This list will help to guide the PCP’s differential and work-up for specific complaints. For example, knowing that a patient is at risk for a second malignancy because of radiation therapy may result in earlier diagnostic imaging, leading to a timelier diagnosis.

The COG screening recommendations that are generally included in a survivorship care plan are appropriate for survivors who are asymptomatic and presenting for routine, exposure-based medical follow-up. More extensive work-ups are presumed to be completed as clinically indicated. Consultation with a pediatric long-term follow-up clinic is also encouraged, particularly if a concern arises.

A complementary set of patient education materials, known as “Health Links,” accompany the COG guidelines to broaden their application and enhance patient follow-up visits. A survivorship care plan and the COG Guidelines help ensure that CCSs receive appropriate ongoing follow-up based on their history. A collaborative approach between Oncology and PCPs is essential to improve the quality of care for CCSs and to maintain the long-term health of this vulnerable population.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jean M. Tersak, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, 4401 Penn Avenue, 5th Floor Plaza Building, Pittsburgh, PA 15224; [email protected].

1. Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2002. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:653-663.

3. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572-1582.

4. Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4401-4409.

5. Feuerstein M. Defining cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:5-7.

6. McCabe MS, Jacobs LA. Clinical update: survivorship care—models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:e1-e8.

7. Oeffinger K, Mertens A, Hudson M, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61-70.

8. Mueller EL, Park ER, Davis MM. What the affordable care act means for survivors of pediatric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:615-617.

9. Oeffinger KC. Longitudinal risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2003;27:143-167.

10. Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CE, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016:1-15.

11. Schwartz CL. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the late effects of therapy. Oncologist. 1999;4:45-54.

12. Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated March 31, 2016. Available at: www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-hp-pdq. Accessed June 2, 2016.

13. Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer, Version 4.0. Monrovia CA: Children’s Oncology Group. 2013. Available at: www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed June 2, 2016.

14. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council, eds. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

15. Commission on Cancer [Internet]. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2015. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed June 2, 2016.

16. Askins MA, Moore BD. Preventing neurocognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1160-1171.

17. McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202-207.

18. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117-5124.

19. Potosky AL, Han PKJ, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

20. Gilbert SM, Miller DC, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Cancer survivorship: challenges and changing paradigms. J Urol. 2008;179:431-438.

21. Renders CM, Valk GD, de Sonnaville JJ, et al. Quality of care for patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus—a long-term comparison of two quality improvement programmes in the Netherlands. Diabet Med. 2003;20:846-852.

22. Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, et al. An evaluation of a shared primary and secondary care nephrology service for managing patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:103-114.

23. Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712-1719.

24. Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:118-124.

1. Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2002. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/. Accessed May 26, 2016.

2. Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:653-663.

3. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572-1582.

4. Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4401-4409.

5. Feuerstein M. Defining cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:5-7.

6. McCabe MS, Jacobs LA. Clinical update: survivorship care—models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:e1-e8.

7. Oeffinger K, Mertens A, Hudson M, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61-70.

8. Mueller EL, Park ER, Davis MM. What the affordable care act means for survivors of pediatric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:615-617.

9. Oeffinger KC. Longitudinal risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2003;27:143-167.

10. Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CE, et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016:1-15.

11. Schwartz CL. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the late effects of therapy. Oncologist. 1999;4:45-54.

12. Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated March 31, 2016. Available at: www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-hp-pdq. Accessed June 2, 2016.

13. Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer, Version 4.0. Monrovia CA: Children’s Oncology Group. 2013. Available at: www.survivorshipguidelines.org. Accessed June 2, 2016.

14. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council, eds. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

15. Commission on Cancer [Internet]. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2015. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed June 2, 2016.

16. Askins MA, Moore BD. Preventing neurocognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1160-1171.

17. McCabe MS, Jacobs L. Survivorship care: models and programs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:202-207.

18. Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117-5124.

19. Potosky AL, Han PKJ, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

20. Gilbert SM, Miller DC, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Cancer survivorship: challenges and changing paradigms. J Urol. 2008;179:431-438.

21. Renders CM, Valk GD, de Sonnaville JJ, et al. Quality of care for patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus—a long-term comparison of two quality improvement programmes in the Netherlands. Diabet Med. 2003;20:846-852.

22. Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, et al. An evaluation of a shared primary and secondary care nephrology service for managing patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:103-114.

23. Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712-1719.

24. Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:118-124.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use the survivorship care plan from the patient’s primary oncologist to guide your screening and management of late effects. C

› Apply the Children’s Oncology Group Guidelines, which are risk-based, exposure-related, clinical practice guidelines, to direct screening and management of late effects in survivors of pediatric malignancies. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series