User login

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

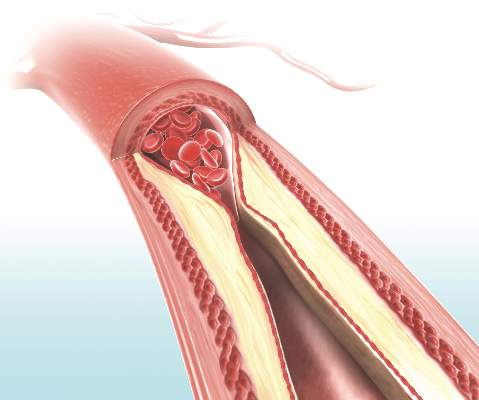

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Despite the favorable effect of estrogen on atherosclerosis in early postmenopausal women in the ELITE trial, the relevance of these results to clinical coronary heart disease events remains questionable. The trial assessed only surrogate measures of coronary heart disease and was not designed or powered to assess clinical events. The occurrence of myocardial infarction and stroke involves not only atherosclerotic plaque formation but also plaque rupture and thrombosis. Any changes in these latter two phenomena would not be captured by the CIMT measurements in ELITE — a point of particular interest, given that postmenopausal hormone therapy may promote thrombosis and inflammation. A final caution is that the available clinical data in support of the timing hypothesis are suggestive but inconsistent.

Guidelines from various professional organizations currently caution against using postmenopausal hormone therapy for the purpose of preventing cardiovascular events. Although the ELITE trial results support the hypothesis that postmenopausal hormone therapy may have more favorable effects on atherosclerosis when initiated soon after menopause, extrapolation of these results to clinical events would be premature, and the present guidance remains prudent.

Dr. John F. Keaney, Jr., is at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester and is an associate editor at the New England Journal of Medicine, and Dr. Caren G. Solomon is a deputy editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1602846).

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

Hormone therapy – estradiol with or without progesterone – only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause onset, according to a report published online March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The “hormone-timing hypothesis” posits that hormone therapy’s beneficial effects on atherosclerosis depend on the timing of initiating that therapy relative to menopause. To test this hypothesis, researchers began the ELITE study (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) in 2002, using serial noninvasive measurements of carotid-artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a marker of atherosclerosis progression.

Several other studies since 2002 have reported that the timing hypothesis appears to be valid, wrote Dr. Howard N. Hodis of the Atherosclerosis Research Unit, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and his associates.

Their single-center trial involved 643 healthy postmenopausal women who had no diabetes and no evidence of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and who were randomly assigned to receive either daily oral estradiol or a matching placebo for 5 years. Women who had an intact uterus and took active estradiol also received a 4% micronized progesterone vaginal gel, while those who had an intact uterus and took placebo also received a matching placebo gel.

The participants were stratified according to the number of years they were past menopause: less than 6 years (271 women in the “early” group) or more than 10 years (372 in the “late” group).

A total of 137 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to active estradiol, while 134 women in the early group and 186 women in the late group were assigned to placebo. As expected, serum estradiol levels were at least 3 times higher among women assigned to active treatment, compared with those assigned to placebo.

The primary outcome – the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression – differed by timing of the initiation of treatment. In the “early” group, the mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo.

In contrast, in the “late” group, the rates of CIMT progression were not significantly different between estradiol and placebo, the investigators wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1221-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241).

This beneficial effect remained significant in a sensitivity analysis restricted only to study participants who showed at least 80% adherence to their assigned treatment. The benefit also remained significant in a post-hoc analysis comparing women who took estradiol alone against those who took estradiol plus progestogen, as well as in a separate analysis comparing women who used lipid-lowering and/or hypertensive medications against those who did not.

The findings add further evidence in favor of the hormone timing hypothesis. The effect of estradiol therapy on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = .007 for the interaction), the researchers wrote.

Cardiac computer tomography (CT) was used as a different method of assessing coronary atherosclerosis in a subgroup of 167 women in the early group (88 receiving estradiol and 79 receiving placebo) and 214 in the late group (101 receiving estradiol and 113 receiving placebo). The timing of estradiol treatment did not affect coronary artery calcium and other cardiac CT measures. This is consistent with previous reports that hormone therapy has no significant effect on established lesions in the coronary arteries, the researchers wrote.

The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Estradiol only limits the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis if it is initiated within 6 years of menopause, not later.

Major finding: The mean CIMT progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo, but only in women who initiated hormone therapy within 6 years of menopause onset.

Data source: A single-center randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 643 healthy postmenopausal women treated for 5 years.

Disclosures: The ELITE trial was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hodis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to GE and TherapeuticsMD.