User login

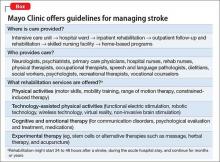

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.