User login

Approximately 1 in 5 Americans report childhood sexual abuse.1 While 50% to 65% of child sexual abuse occurs in the absence of pedophilic interests and is thought to be driven by additional factors such as the availability of an appropriate sexual partner,2,3 a substantial portion of childhood sexual abuse is perpetrated by individuals with pedophilia.

However, many individuals with pedophilic interests never have sexual contact with a child or the penal system. This non-offending pedophile group reports a greater prevalence of psychiatric symptoms compared with the general population, but given the intense stigmatization of their preferences, they are largely psychiatrically underrecognized and underserved. This article focuses on the unique psychiatric needs of this neglected population. By understanding and addressing the treatment needs of these patients, psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can serve a pivotal role in decreasing stigma, promoting wellness, and preventing sexual abuse.

Understanding the terminology

DSM-5 defines paraphilia as “any intense and persistent sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physiologically mature, consenting human partners.”4 The addition of the word “disorder” to the paraphilias was introduced in DSM-5 to distinguish between paraphilias that are not of clinical concern and paraphilic disorders that cause distress or impairment to the individual, or whereby satisfaction entails personal harm or risk of harm to others. As outlined in DSM-5, pedophilic disorder refers to at least 6 months of recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child.4 The individual has either acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Lastly, the individual must be at least age 16 years and at least 5 years older than the child. Sexual attraction to peri- or postpubescent minors is not considered a psychiatric disorder, but is illegal.

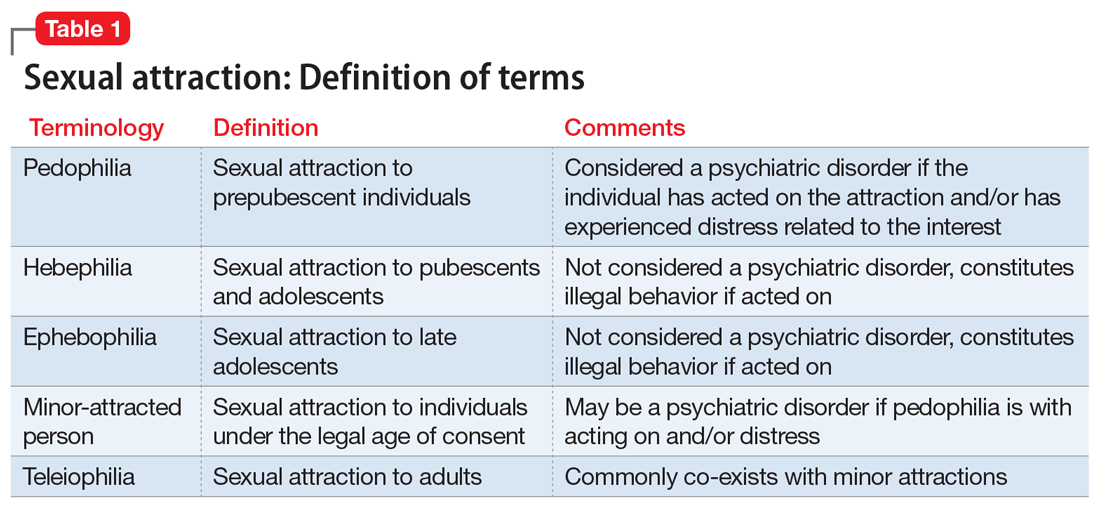

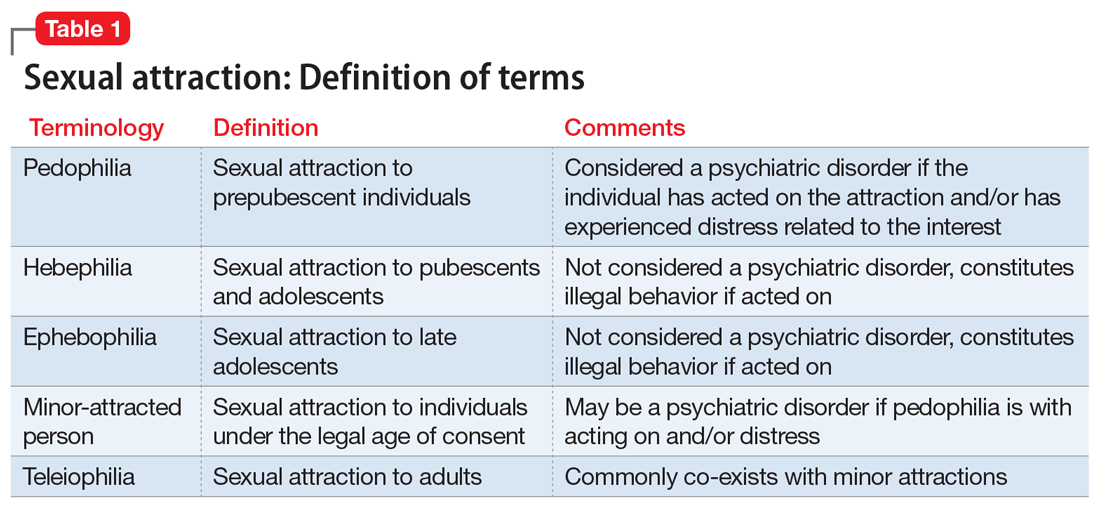

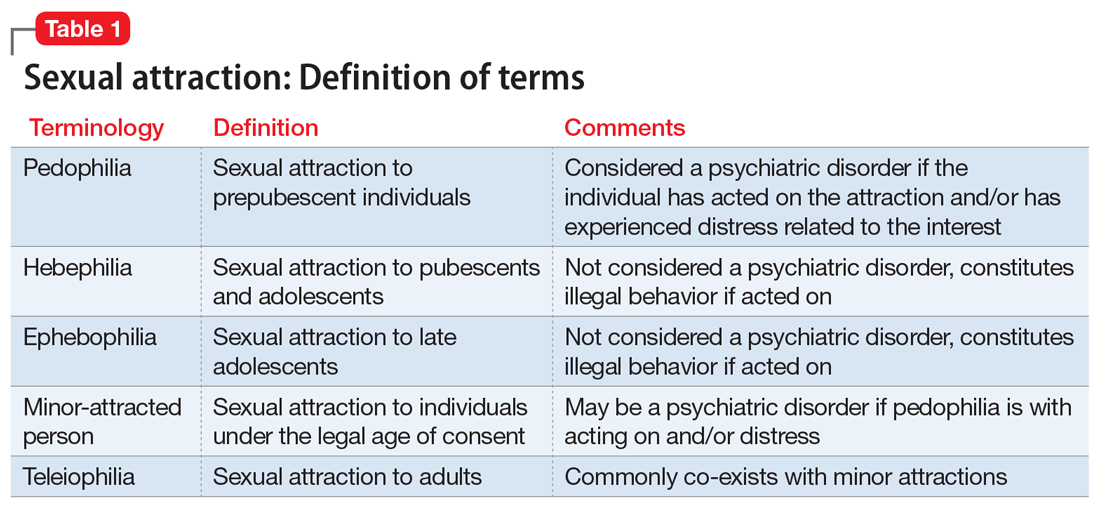

Coined by B4U-ACT (www.b4uact.org), the term minor-attracted person (MAP) refers to individuals with sexual attraction to individuals who are minors or below the legal age of consent. MAP is an umbrella term that includes sexual attraction to prepubescent individuals but also includes sexual attraction to peri- and postpubescent individuals (Table 1). A MAP may or may not meet criteria for pedophilia or pedophilic disorder, based on the age of their sexual interest and whether they have experienced distress or acted on the attraction. Although many individuals with minor attraction identify with the term MAP, not all do. The term has been critiqued for being too inclusive and conflating pedophilia with minor attractions.

It is important to keep in mind that the terms pedophilia and minor attraction are not synonymous with childhood sexual abuser or “child molester” because neither term specifies whether the individual has had sexual contact with a child or legal consequences. The terms offending/non-offending and acting/non-acting are used to specify the presence of sexual contact with a child, and do not convey any clinical information.

Prevalence data

The true prevalence of pedophilia and/or attraction to minors is unknown, and estimates vary considerably. In some studies, 1% to 4% of the general population were thought to have persistent attraction to prepubescent children.5,6 In a community sample of 8,718 German men, 4.1% reported sexual fantasies involving prepubescent children, 3.2% reported sexual offending against prepubescent children, and 0.1% reported a pedophilic sexual preference.5 In a study of 367 adult German men surveyed from the community, 15.5% reported fantasies (9.5% daydream and 6.0% masturbation fantasies) involving prepubescent children.7

Stigmatization of minor-attracted persons

Stigmatization is the process of forming negative evaluations of an individual or groups of people based on limited characteristics.8,9 MAPs are a highly stigmatized group. This stigmatization can be profound, regardless of whether the MAP has had sexual contact with a child. A public survey of nearly 1,000 individuals showed that 39% believed that non-acting MAPs should be incarcerated, and 14% believed that they would be “better off dead.”10 Societal misconceptions of minor attraction are pervasive and include10:

- MAP sexual orientation is a choice

- MAPs cannot resist their sexual urges

- all MAPs have offended, or inevitably will

- MAPs will not respond to therapy

- MAPs are fundamentally predatory and immoral.

Continue to: In addition to...

In addition to societal stigma, internalized stigma among MAPs has been documented. Lievesley et al9 found that MAPs who engaged in suppression of unwanted thought strategies had higher levels of shame and guilt, low levels of hope, and a propensity to actively avoid children. Similarly, Grady et al11 surveyed 293 MAPs and found prominent themes of viewing themselves as “bad.”

Psychiatric presentations include suicidal ideation

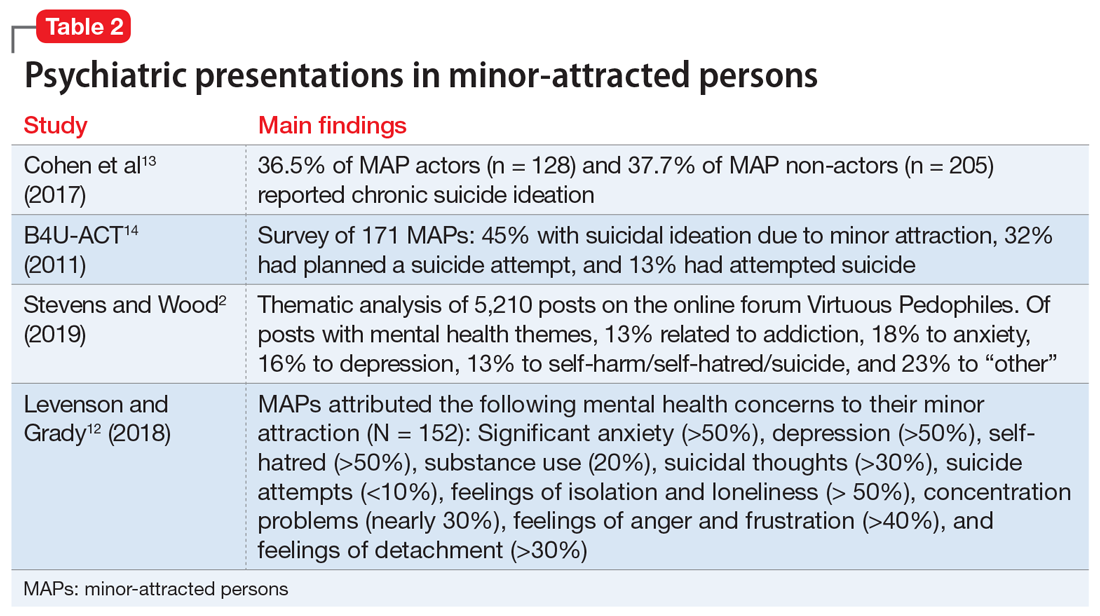

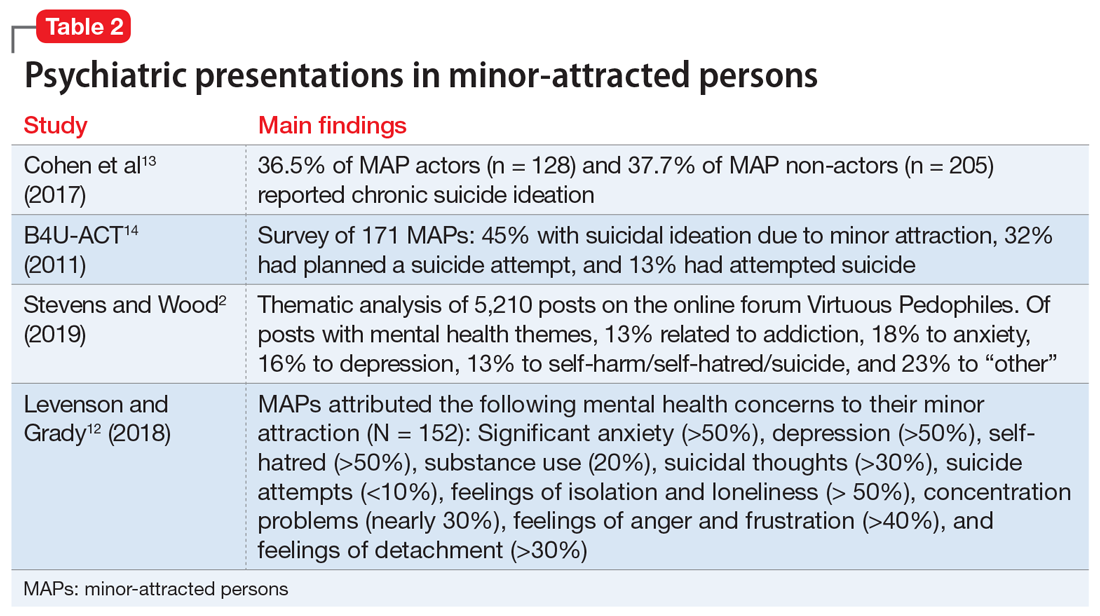

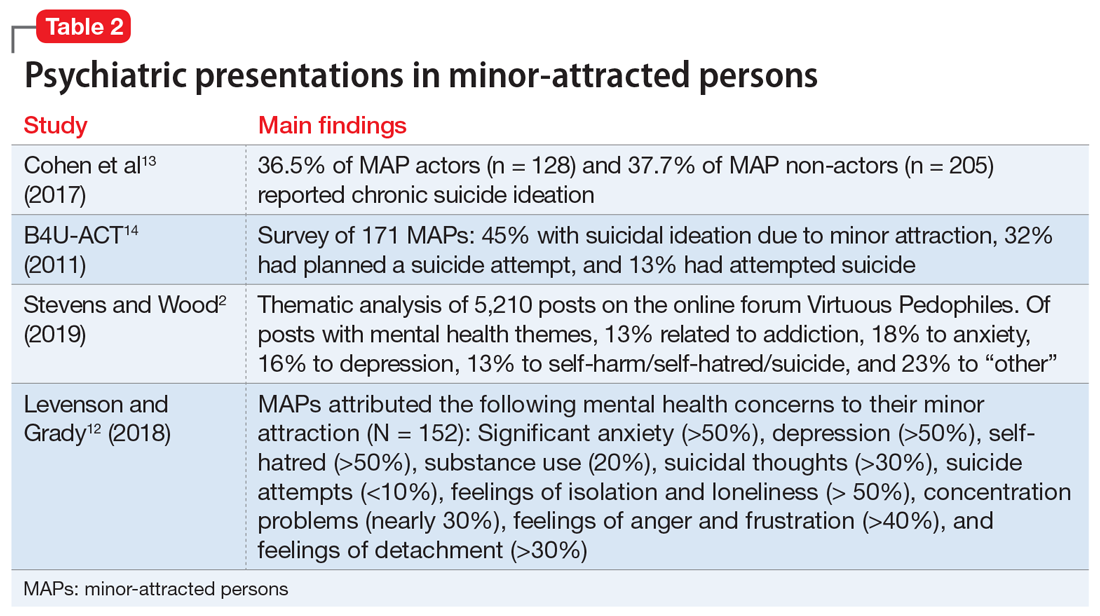

Many MAPs, including non-acting MAPs, internalize this societal stigma, which contributes to a significant mental health burden.12 A survey of 342 MAP actors and 223 MAP non-actors revealed that one-third of both groups reported chronic suicidal ideation.13 In addition, online surveys conducted by B4U-ACT and Virtuous Pedophiles (www.virped.org)—both internet-based organizations dedicated to supporting non-acting MAPs—have provided similar results. In a 2011 B4U-ACT survey, nearly one-half of participants reported suicidal ideation due to their minor attraction, 32% had planned suicide attempts, and 13% had non-fatal suicide attempts. Notably, the age group with the most prevalent suicidal ideation was age 14 to 16 years,14 which makes minor attraction a prominent risk factor for suicidal ideation among patients seen by child psychiatrists.

A 2019 thematic analysis of 5,210 posts on the Virtuous Pedophiles website showed high rates of addiction, anxiety, depression, self-harm, self-hatred, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among MAPs.2 The majority of posts regarding substance use described such use as a means of dissociation. One post read, “…There are days I cannot bear to be sober … I … drink myself into a coma.” Anxiety themes regarding the ability to have a meaningful relationship with an age-appropriate partner and concerns about being “outed” followed by public persecution were prominent. Posts regarding self-injurious and suicidal behavior were common: “I want to kill myself so badly … I have to mutilate myself as punishment for my attractions. I wish myself dead. I don’t want to be attracted to children; I despise myself for fantasizing about them.”2

A study that analyzed a survey of 152 MAPs sampled from websites such as Virtuous Pedophiles and others showed >50% of respondents had strong feelings of isolation and loneliness, nearly 30% had extreme difficulty with concentration, >40% had significant anger and frustration, and >30% were struggling with feelings of detachment.12 Notably, the respondents attributed these difficulties to their minor attraction.12 Table 22,12-14 summarizes the findings of studies evaluating psychiatric symptoms in MAPs.

Consider OCD, hypersexuality

It is important to be aware that an attraction to minors may be a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or hypersexuality.15 Pedophilia-themed OCD (POCD) is a manifestation of OCD in which the individual experiences shame, fear, and excessive worry related to sexual attraction to children. Typically, individuals with POCD experience sexual thoughts of children as ego-dystonic, whereas MAPs experience such thoughts as ego-syntonic and arousing.15 However, much like individuals with POCD, MAPs also experience sexual thoughts of minors as distressing. Initial presentations of POCD may be confused with MAPs or pedophilia because of the overlap of symptoms such as anxiety, shame, distress, or suicidal ideation related to the idea of child sexual interests. The distinguishing feature of POCD is the absence of sexual arousal to children.

Continue to: Clinical presentations of...

Clinical presentations of hypersexuality may include sexual arousal to children. These individuals are distinguished from MAPs or those with pedophilia because they lack a preferred or sustained sexual interest in this group. On the contrary, individuals with hypersexuality present with a diversity of sexual interests explained by their high libido. Some individuals, however, may meet criteria for both hypersexuality and pedophilia. These individuals may pose a higher risk of sexual offending due to the presence of a heightened sexual drive and pedophilic interests, and thereby may require more intensive treatment, such as biologic treatment.

Focus on individualized treatment needs

Understanding the treatment needs of MAPs means understanding the goals of the individual MAP. Improving self-esteem, decreasing social isolation, and managing stigma are common treatment goals among MAPs.16 Levenson and Grady12 found that most MAPs identified treatment goals unrelated to sexual interests, such as addressing depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. A smaller percentage identified sexual frustration related to the absence of healthy sexual outlets. Because many MAPs identify common psychiatric treatment needs, most clinicians should be equipped to foster a nonjudgmental therapeutic alliance to treat these patients. Effective treatment outcomes occur when comorbid psychiatric illnesses are treated as well as addressing the internal stigmatization that many MAPs experience.

Specialized treatment may be indicated for individuals who request treatment specific to sexual interests. This may include safety planning, including developing support systems to decrease the risk around children. For MAPs who have been unsuccessful at managing their sexual interests, pharmacotherapy may be an option. To date, research on pharmacotherapy for pedophilia is largely limited to studies of sexual offenders. Testosterone-lowering medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue treatment constitutes the most effective treatment for patients who are not helped by conventional psychotherapeutic interventions.17 Other psychotropic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or naltrexone, have not demonstrated efficacy outside of case reports.17

Addressing barriers to care

MAPs have a strong desire but significant hesitation when seeking mental health treatment.13,18 Nearly half (47%) of the 154 MAP respondents in the Levenson and Grady12 survey had never told anyone about their minor attraction. MAPs are understandably hesitant to disclose these thoughts and feelings due to fear of public exposure and intense stigmatization, as well as potential punitive and legal consequences.18,19 One post from the 2011 B4U-ACT online survey read, “Parents will disown you; teachers will report you; friends will abandon you … people in my situation can’t discuss this without serious risk of persecution and/or harassment.”14 In this survey, 78% of respondents feared a negative reaction by the professional, 78% feared being reported to law enforcement, and 68% feared being reported to family, an employer, or the community.14 This hesitancy due to fear of being exposed even extended to accessing self-help books, informational websites, and online forums, even though these sources are strongly desired and perceived as helpful.20

Even if MAPs were to decide to seek help, the lack of specific training and experience among psychiatrists make them unlikely to find it in the medical field.21 Furthermore, MAPs who desire help often worry it will be inadequate and they will be misunderstood by their clinicians.22 According to the Levenson and Grady survey,12 when asked what they would like most from therapy, most MAPs said they would want the treatment to focus on depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem rather than on sexual interest. In the B4U-ACT survey,14 many respondents identified the need for treatment of issues surrounding their sexual attraction, such as assistance in learning how to live in society with the attraction, dealing with society’s negative response to the attraction, and improving their self-concept in the presence of the extreme shame associated with the attraction. However, many MAPs find that clinicians tend to focus on protecting society from them, rather than on offering general psychiatric treatment or treatment focused on improving their well-being.18 This inability to locate appropriate services is known to exacerbate depression, suicidality, fear, anxiety, hopelessness, and substance abuse among MAPs.18 There is also evidence that individuals with minor attraction who are in a negative affective state are more likely to act on their attractions.23

Continue to: An ethical responsibility

An ethical responsibility. Physicians have a long-recognized responsibility to participate in activities to protect and promote the health of the public. The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics includes “justice,” or treating patients fairly and equitably.24 This includes patients who have pedophilic interests. Unfortunately, the stigma associated with individuals who have sexual attraction to children is pervasive in our society, including among medical professionals. The first consideration in treating MAPs is to overcome the stigmatization within our field, to remember that as physicians we took an oath to provide treatment fairly, equitably, and in accordance with the patient’s rights and entitlement.24 This includes listening to MAPs’ treatment needs. Not all MAPs want or need treatment related to their sexual interest. As is the case with all patients, listening to the individual’s chief complaint is paramount. If a patient’s treatment needs are beyond the clinician’s expertise, the patient should be referred to another clinician.

Mandated reporting. MAPs may not engage in psychiatric treatment for fear of being reported to authorities as a result of mandated reporting laws. Although the circumstances under which mandated reporting may be required vary by jurisdiction, they generally include situations in which the health care professional has reasonable cause to believe that a child is suffering from abuse or neglect. A patient’s report of sexual urges and fantasies to have sexual contact with minors is not sufficient for mandated reporting. While professionals vary in their interpretation of mandated reporting laws, sexual thoughts alone do not meet the threshold for mandated reporting. Mandated reporting duties should be discussed when first meeting a patient with minor attraction. For clinicians who are uneasy about such distinctions, either supervision or not working with such patients is the solution.

The importance of providing competent and individualized treatment to MAPs is 2-fold. First, individuals who are experiencing psychiatric symptoms deserve to have access treatment. Second, providing psychiatric treatment to individuals with minor attractions is a step toward preventing child sexual abuse. The Prevention Project Dunkelfeld in Germany used public service announcements to advertise confidential treatment for individuals who had sexual interest in children.25 Many of the participants were interested in mental health treatment unrelated to their sexual interests. Such projects may help us understand the best way to meet the treatment needs of minor-attracted individuals, as well as reduce child sexual abuse. As psychiatrists, we can stop making the problem worse by withholding psychiatric treatment from an important population.

Resources for MAPs and clinicians

Currently, resources for MAPs and clinicians are limited. MAPs can communicate and find support among other MAPs in online forums (see Related Resources). These websites provide online peer support groups and guides for seeking therapy. Information for mental health professionals, including available literature, research projects, clinicians who provide specialized treatment, and a monthly “dialog on therapy” can be found on the B4U-ACT and the Global Prevention Project websites. However, beyond the DSM-5 definitions, psychiatric education and training on this topic is almost entirely lacking.

In light of the information discussed in this article, several important issues remain, including how psychiatrists can best reach this population, and how they can work toward decreasing stigma so they can provide meaningful care. The solutions start with education. Educating psychiatrists about this important population can decrease stigma and facilitate appropriate, compassionate care to these patients, with the result of improving the mental health of people with minor attraction and decreasing the incidence of child sexual abuse.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Minor-attracted persons report a high prevalence of general psychiatric symptoms that often go untreated due to a lack of willing clinicians with appropriate expertise. Providing psychiatric treatment to these patients can improve their mental health and possibly decrease the incidence of individuals who act on their attractions.

Related Resources

- B4U-ACT. www.b4uact.org • The Global Prevention Project. http://theglobalprevention project.org

- Virtuous Pedophiles. www.virped.org

Drug Brand Names

Naltrexone • ReVia

1. Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(10):1205-1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008

2. Stevens E, Wood J. “I despise myself for thinking about them.” A thematic analysis of the mental health implications and employed coping mechanisms of self-reported non-offending minor attracted persons. J Child Sex Abus. 2019;28(8):968-989. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1657539

3. Sorrentino R. Normal human sexuality and sexual and gender identity disorders: paraphilias. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruis P, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2012:2093-2094.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:685-705.

5. Dombert B, Schmidt AF, Banse R, et al. How common is men’s self-reported sexual interest in prepubescent children? J Sex Res. 2016;53(2):214-23. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1020108

6. Seto MC. Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: theory, assessment, and intervention. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; 2018.

7. Ahlers CJ, Schaefer GA, Mundt IA, et al. How unusual are the contents of paraphilias? Paraphilia-associated sexual arousal patterns in a community-based sample of men. J Sex Med. 2011;8(5):1362-1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01597.x

8. Corrigan PW, Roe D, Tsang HWH. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: lessons for therapists and advocates. Wiley Blackwell; 2011:55-114.

9. Lievesley R, Harper CA, Elliott H. The internalization of social stigma among minor-attracted persons: implications for treatment. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(4):1291-1304. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01569-x

10. Jahnke S, Imhoff R, Hoyer J. Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: two comparative surveys. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(1):21-34. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0312-4

11. Grady MD, Levenson JS, Mesias G, et al. “‘I can’t talk about that”: Stigma and fear as barriers to preventative services for minor-attracted persons. Stigma and Health. 2019;4(4):400-410. doi: 10.1037/sah0000154

12. Levenson JS, Grady MD. Preventing sexual abuse: perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sex Abuse. 2019;31(8):991-1013. doi: 10.1177/1079063218797713

13. Cohen L, Ndukwe N, Yaseen Z, et al. Comparison of self-identified minor-attracted persons who have and have not successfully refrained from sexual activity with children. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44(3):217-230. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1377129

14. B4U-ACT. Awareness of sexuality in youth, suicidality, and seeking care. 2011. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/research/survey-results/spring-2011-survey

15. Bruce SL, Ching THW, Williams MT. Pedophilia-themed obsessive-compulsive disorder: assessment, differential diagnosis, and treatment with exposure and response prevention. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(2):389-402. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1031-4

16. Levenson JS, Grady MD, Morin JW. Beyond the “ick factor”: counseling non-offending persons with pedophilia. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2020;48:380-388. doi: 10.007/s10615-019-00712-4

1 7. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1744723

18. B4U-ACT. Principles and perspectives of practice. 2017. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/about-us/principles-and-perspectives-of-practice/

19. McPhail IV, Stephens S, Heasman A. Legal and ethical issues in treating clients with pedohebephilic interests. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2018;59(4):369-381. doi:10.1037/cap0000157

20. Levenson JS, Willis GM, Vicencio CP. Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: implications for prevention of sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(2):99-120. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116

21. Sorrentino R. DSM-5 and paraphilias: what psychiatrists need to know. Psychiatric Times. November 28, 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/dsm-5-and-paraphilias-what-psychiatrists-need-know

22. Cantor JM, McPhail IV. Non-offending pedophiles. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2016;8:121-128. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0076-z

23. Ward T, Louden K, Hudson SM, et al. A descriptive model of the offense chain for child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10(4):452-472. doi:10.1177/088626095010004005

24. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/principles-of-medical-ethics.pdf

25. Beier KM, Grundmann D, Kuhle LF, et al. The German Dunkelfeld project: a pilot study to prevent child sexual abuse and the use of child abusive images. J Sex Med. 2015;12(2):529-42. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12785

Approximately 1 in 5 Americans report childhood sexual abuse.1 While 50% to 65% of child sexual abuse occurs in the absence of pedophilic interests and is thought to be driven by additional factors such as the availability of an appropriate sexual partner,2,3 a substantial portion of childhood sexual abuse is perpetrated by individuals with pedophilia.

However, many individuals with pedophilic interests never have sexual contact with a child or the penal system. This non-offending pedophile group reports a greater prevalence of psychiatric symptoms compared with the general population, but given the intense stigmatization of their preferences, they are largely psychiatrically underrecognized and underserved. This article focuses on the unique psychiatric needs of this neglected population. By understanding and addressing the treatment needs of these patients, psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can serve a pivotal role in decreasing stigma, promoting wellness, and preventing sexual abuse.

Understanding the terminology

DSM-5 defines paraphilia as “any intense and persistent sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physiologically mature, consenting human partners.”4 The addition of the word “disorder” to the paraphilias was introduced in DSM-5 to distinguish between paraphilias that are not of clinical concern and paraphilic disorders that cause distress or impairment to the individual, or whereby satisfaction entails personal harm or risk of harm to others. As outlined in DSM-5, pedophilic disorder refers to at least 6 months of recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child.4 The individual has either acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Lastly, the individual must be at least age 16 years and at least 5 years older than the child. Sexual attraction to peri- or postpubescent minors is not considered a psychiatric disorder, but is illegal.

Coined by B4U-ACT (www.b4uact.org), the term minor-attracted person (MAP) refers to individuals with sexual attraction to individuals who are minors or below the legal age of consent. MAP is an umbrella term that includes sexual attraction to prepubescent individuals but also includes sexual attraction to peri- and postpubescent individuals (Table 1). A MAP may or may not meet criteria for pedophilia or pedophilic disorder, based on the age of their sexual interest and whether they have experienced distress or acted on the attraction. Although many individuals with minor attraction identify with the term MAP, not all do. The term has been critiqued for being too inclusive and conflating pedophilia with minor attractions.

It is important to keep in mind that the terms pedophilia and minor attraction are not synonymous with childhood sexual abuser or “child molester” because neither term specifies whether the individual has had sexual contact with a child or legal consequences. The terms offending/non-offending and acting/non-acting are used to specify the presence of sexual contact with a child, and do not convey any clinical information.

Prevalence data

The true prevalence of pedophilia and/or attraction to minors is unknown, and estimates vary considerably. In some studies, 1% to 4% of the general population were thought to have persistent attraction to prepubescent children.5,6 In a community sample of 8,718 German men, 4.1% reported sexual fantasies involving prepubescent children, 3.2% reported sexual offending against prepubescent children, and 0.1% reported a pedophilic sexual preference.5 In a study of 367 adult German men surveyed from the community, 15.5% reported fantasies (9.5% daydream and 6.0% masturbation fantasies) involving prepubescent children.7

Stigmatization of minor-attracted persons

Stigmatization is the process of forming negative evaluations of an individual or groups of people based on limited characteristics.8,9 MAPs are a highly stigmatized group. This stigmatization can be profound, regardless of whether the MAP has had sexual contact with a child. A public survey of nearly 1,000 individuals showed that 39% believed that non-acting MAPs should be incarcerated, and 14% believed that they would be “better off dead.”10 Societal misconceptions of minor attraction are pervasive and include10:

- MAP sexual orientation is a choice

- MAPs cannot resist their sexual urges

- all MAPs have offended, or inevitably will

- MAPs will not respond to therapy

- MAPs are fundamentally predatory and immoral.

Continue to: In addition to...

In addition to societal stigma, internalized stigma among MAPs has been documented. Lievesley et al9 found that MAPs who engaged in suppression of unwanted thought strategies had higher levels of shame and guilt, low levels of hope, and a propensity to actively avoid children. Similarly, Grady et al11 surveyed 293 MAPs and found prominent themes of viewing themselves as “bad.”

Psychiatric presentations include suicidal ideation

Many MAPs, including non-acting MAPs, internalize this societal stigma, which contributes to a significant mental health burden.12 A survey of 342 MAP actors and 223 MAP non-actors revealed that one-third of both groups reported chronic suicidal ideation.13 In addition, online surveys conducted by B4U-ACT and Virtuous Pedophiles (www.virped.org)—both internet-based organizations dedicated to supporting non-acting MAPs—have provided similar results. In a 2011 B4U-ACT survey, nearly one-half of participants reported suicidal ideation due to their minor attraction, 32% had planned suicide attempts, and 13% had non-fatal suicide attempts. Notably, the age group with the most prevalent suicidal ideation was age 14 to 16 years,14 which makes minor attraction a prominent risk factor for suicidal ideation among patients seen by child psychiatrists.

A 2019 thematic analysis of 5,210 posts on the Virtuous Pedophiles website showed high rates of addiction, anxiety, depression, self-harm, self-hatred, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among MAPs.2 The majority of posts regarding substance use described such use as a means of dissociation. One post read, “…There are days I cannot bear to be sober … I … drink myself into a coma.” Anxiety themes regarding the ability to have a meaningful relationship with an age-appropriate partner and concerns about being “outed” followed by public persecution were prominent. Posts regarding self-injurious and suicidal behavior were common: “I want to kill myself so badly … I have to mutilate myself as punishment for my attractions. I wish myself dead. I don’t want to be attracted to children; I despise myself for fantasizing about them.”2

A study that analyzed a survey of 152 MAPs sampled from websites such as Virtuous Pedophiles and others showed >50% of respondents had strong feelings of isolation and loneliness, nearly 30% had extreme difficulty with concentration, >40% had significant anger and frustration, and >30% were struggling with feelings of detachment.12 Notably, the respondents attributed these difficulties to their minor attraction.12 Table 22,12-14 summarizes the findings of studies evaluating psychiatric symptoms in MAPs.

Consider OCD, hypersexuality

It is important to be aware that an attraction to minors may be a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or hypersexuality.15 Pedophilia-themed OCD (POCD) is a manifestation of OCD in which the individual experiences shame, fear, and excessive worry related to sexual attraction to children. Typically, individuals with POCD experience sexual thoughts of children as ego-dystonic, whereas MAPs experience such thoughts as ego-syntonic and arousing.15 However, much like individuals with POCD, MAPs also experience sexual thoughts of minors as distressing. Initial presentations of POCD may be confused with MAPs or pedophilia because of the overlap of symptoms such as anxiety, shame, distress, or suicidal ideation related to the idea of child sexual interests. The distinguishing feature of POCD is the absence of sexual arousal to children.

Continue to: Clinical presentations of...

Clinical presentations of hypersexuality may include sexual arousal to children. These individuals are distinguished from MAPs or those with pedophilia because they lack a preferred or sustained sexual interest in this group. On the contrary, individuals with hypersexuality present with a diversity of sexual interests explained by their high libido. Some individuals, however, may meet criteria for both hypersexuality and pedophilia. These individuals may pose a higher risk of sexual offending due to the presence of a heightened sexual drive and pedophilic interests, and thereby may require more intensive treatment, such as biologic treatment.

Focus on individualized treatment needs

Understanding the treatment needs of MAPs means understanding the goals of the individual MAP. Improving self-esteem, decreasing social isolation, and managing stigma are common treatment goals among MAPs.16 Levenson and Grady12 found that most MAPs identified treatment goals unrelated to sexual interests, such as addressing depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. A smaller percentage identified sexual frustration related to the absence of healthy sexual outlets. Because many MAPs identify common psychiatric treatment needs, most clinicians should be equipped to foster a nonjudgmental therapeutic alliance to treat these patients. Effective treatment outcomes occur when comorbid psychiatric illnesses are treated as well as addressing the internal stigmatization that many MAPs experience.

Specialized treatment may be indicated for individuals who request treatment specific to sexual interests. This may include safety planning, including developing support systems to decrease the risk around children. For MAPs who have been unsuccessful at managing their sexual interests, pharmacotherapy may be an option. To date, research on pharmacotherapy for pedophilia is largely limited to studies of sexual offenders. Testosterone-lowering medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue treatment constitutes the most effective treatment for patients who are not helped by conventional psychotherapeutic interventions.17 Other psychotropic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or naltrexone, have not demonstrated efficacy outside of case reports.17

Addressing barriers to care

MAPs have a strong desire but significant hesitation when seeking mental health treatment.13,18 Nearly half (47%) of the 154 MAP respondents in the Levenson and Grady12 survey had never told anyone about their minor attraction. MAPs are understandably hesitant to disclose these thoughts and feelings due to fear of public exposure and intense stigmatization, as well as potential punitive and legal consequences.18,19 One post from the 2011 B4U-ACT online survey read, “Parents will disown you; teachers will report you; friends will abandon you … people in my situation can’t discuss this without serious risk of persecution and/or harassment.”14 In this survey, 78% of respondents feared a negative reaction by the professional, 78% feared being reported to law enforcement, and 68% feared being reported to family, an employer, or the community.14 This hesitancy due to fear of being exposed even extended to accessing self-help books, informational websites, and online forums, even though these sources are strongly desired and perceived as helpful.20

Even if MAPs were to decide to seek help, the lack of specific training and experience among psychiatrists make them unlikely to find it in the medical field.21 Furthermore, MAPs who desire help often worry it will be inadequate and they will be misunderstood by their clinicians.22 According to the Levenson and Grady survey,12 when asked what they would like most from therapy, most MAPs said they would want the treatment to focus on depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem rather than on sexual interest. In the B4U-ACT survey,14 many respondents identified the need for treatment of issues surrounding their sexual attraction, such as assistance in learning how to live in society with the attraction, dealing with society’s negative response to the attraction, and improving their self-concept in the presence of the extreme shame associated with the attraction. However, many MAPs find that clinicians tend to focus on protecting society from them, rather than on offering general psychiatric treatment or treatment focused on improving their well-being.18 This inability to locate appropriate services is known to exacerbate depression, suicidality, fear, anxiety, hopelessness, and substance abuse among MAPs.18 There is also evidence that individuals with minor attraction who are in a negative affective state are more likely to act on their attractions.23

Continue to: An ethical responsibility

An ethical responsibility. Physicians have a long-recognized responsibility to participate in activities to protect and promote the health of the public. The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics includes “justice,” or treating patients fairly and equitably.24 This includes patients who have pedophilic interests. Unfortunately, the stigma associated with individuals who have sexual attraction to children is pervasive in our society, including among medical professionals. The first consideration in treating MAPs is to overcome the stigmatization within our field, to remember that as physicians we took an oath to provide treatment fairly, equitably, and in accordance with the patient’s rights and entitlement.24 This includes listening to MAPs’ treatment needs. Not all MAPs want or need treatment related to their sexual interest. As is the case with all patients, listening to the individual’s chief complaint is paramount. If a patient’s treatment needs are beyond the clinician’s expertise, the patient should be referred to another clinician.

Mandated reporting. MAPs may not engage in psychiatric treatment for fear of being reported to authorities as a result of mandated reporting laws. Although the circumstances under which mandated reporting may be required vary by jurisdiction, they generally include situations in which the health care professional has reasonable cause to believe that a child is suffering from abuse or neglect. A patient’s report of sexual urges and fantasies to have sexual contact with minors is not sufficient for mandated reporting. While professionals vary in their interpretation of mandated reporting laws, sexual thoughts alone do not meet the threshold for mandated reporting. Mandated reporting duties should be discussed when first meeting a patient with minor attraction. For clinicians who are uneasy about such distinctions, either supervision or not working with such patients is the solution.

The importance of providing competent and individualized treatment to MAPs is 2-fold. First, individuals who are experiencing psychiatric symptoms deserve to have access treatment. Second, providing psychiatric treatment to individuals with minor attractions is a step toward preventing child sexual abuse. The Prevention Project Dunkelfeld in Germany used public service announcements to advertise confidential treatment for individuals who had sexual interest in children.25 Many of the participants were interested in mental health treatment unrelated to their sexual interests. Such projects may help us understand the best way to meet the treatment needs of minor-attracted individuals, as well as reduce child sexual abuse. As psychiatrists, we can stop making the problem worse by withholding psychiatric treatment from an important population.

Resources for MAPs and clinicians

Currently, resources for MAPs and clinicians are limited. MAPs can communicate and find support among other MAPs in online forums (see Related Resources). These websites provide online peer support groups and guides for seeking therapy. Information for mental health professionals, including available literature, research projects, clinicians who provide specialized treatment, and a monthly “dialog on therapy” can be found on the B4U-ACT and the Global Prevention Project websites. However, beyond the DSM-5 definitions, psychiatric education and training on this topic is almost entirely lacking.

In light of the information discussed in this article, several important issues remain, including how psychiatrists can best reach this population, and how they can work toward decreasing stigma so they can provide meaningful care. The solutions start with education. Educating psychiatrists about this important population can decrease stigma and facilitate appropriate, compassionate care to these patients, with the result of improving the mental health of people with minor attraction and decreasing the incidence of child sexual abuse.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Minor-attracted persons report a high prevalence of general psychiatric symptoms that often go untreated due to a lack of willing clinicians with appropriate expertise. Providing psychiatric treatment to these patients can improve their mental health and possibly decrease the incidence of individuals who act on their attractions.

Related Resources

- B4U-ACT. www.b4uact.org • The Global Prevention Project. http://theglobalprevention project.org

- Virtuous Pedophiles. www.virped.org

Drug Brand Names

Naltrexone • ReVia

Approximately 1 in 5 Americans report childhood sexual abuse.1 While 50% to 65% of child sexual abuse occurs in the absence of pedophilic interests and is thought to be driven by additional factors such as the availability of an appropriate sexual partner,2,3 a substantial portion of childhood sexual abuse is perpetrated by individuals with pedophilia.

However, many individuals with pedophilic interests never have sexual contact with a child or the penal system. This non-offending pedophile group reports a greater prevalence of psychiatric symptoms compared with the general population, but given the intense stigmatization of their preferences, they are largely psychiatrically underrecognized and underserved. This article focuses on the unique psychiatric needs of this neglected population. By understanding and addressing the treatment needs of these patients, psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians can serve a pivotal role in decreasing stigma, promoting wellness, and preventing sexual abuse.

Understanding the terminology

DSM-5 defines paraphilia as “any intense and persistent sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physiologically mature, consenting human partners.”4 The addition of the word “disorder” to the paraphilias was introduced in DSM-5 to distinguish between paraphilias that are not of clinical concern and paraphilic disorders that cause distress or impairment to the individual, or whereby satisfaction entails personal harm or risk of harm to others. As outlined in DSM-5, pedophilic disorder refers to at least 6 months of recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child.4 The individual has either acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty. Lastly, the individual must be at least age 16 years and at least 5 years older than the child. Sexual attraction to peri- or postpubescent minors is not considered a psychiatric disorder, but is illegal.

Coined by B4U-ACT (www.b4uact.org), the term minor-attracted person (MAP) refers to individuals with sexual attraction to individuals who are minors or below the legal age of consent. MAP is an umbrella term that includes sexual attraction to prepubescent individuals but also includes sexual attraction to peri- and postpubescent individuals (Table 1). A MAP may or may not meet criteria for pedophilia or pedophilic disorder, based on the age of their sexual interest and whether they have experienced distress or acted on the attraction. Although many individuals with minor attraction identify with the term MAP, not all do. The term has been critiqued for being too inclusive and conflating pedophilia with minor attractions.

It is important to keep in mind that the terms pedophilia and minor attraction are not synonymous with childhood sexual abuser or “child molester” because neither term specifies whether the individual has had sexual contact with a child or legal consequences. The terms offending/non-offending and acting/non-acting are used to specify the presence of sexual contact with a child, and do not convey any clinical information.

Prevalence data

The true prevalence of pedophilia and/or attraction to minors is unknown, and estimates vary considerably. In some studies, 1% to 4% of the general population were thought to have persistent attraction to prepubescent children.5,6 In a community sample of 8,718 German men, 4.1% reported sexual fantasies involving prepubescent children, 3.2% reported sexual offending against prepubescent children, and 0.1% reported a pedophilic sexual preference.5 In a study of 367 adult German men surveyed from the community, 15.5% reported fantasies (9.5% daydream and 6.0% masturbation fantasies) involving prepubescent children.7

Stigmatization of minor-attracted persons

Stigmatization is the process of forming negative evaluations of an individual or groups of people based on limited characteristics.8,9 MAPs are a highly stigmatized group. This stigmatization can be profound, regardless of whether the MAP has had sexual contact with a child. A public survey of nearly 1,000 individuals showed that 39% believed that non-acting MAPs should be incarcerated, and 14% believed that they would be “better off dead.”10 Societal misconceptions of minor attraction are pervasive and include10:

- MAP sexual orientation is a choice

- MAPs cannot resist their sexual urges

- all MAPs have offended, or inevitably will

- MAPs will not respond to therapy

- MAPs are fundamentally predatory and immoral.

Continue to: In addition to...

In addition to societal stigma, internalized stigma among MAPs has been documented. Lievesley et al9 found that MAPs who engaged in suppression of unwanted thought strategies had higher levels of shame and guilt, low levels of hope, and a propensity to actively avoid children. Similarly, Grady et al11 surveyed 293 MAPs and found prominent themes of viewing themselves as “bad.”

Psychiatric presentations include suicidal ideation

Many MAPs, including non-acting MAPs, internalize this societal stigma, which contributes to a significant mental health burden.12 A survey of 342 MAP actors and 223 MAP non-actors revealed that one-third of both groups reported chronic suicidal ideation.13 In addition, online surveys conducted by B4U-ACT and Virtuous Pedophiles (www.virped.org)—both internet-based organizations dedicated to supporting non-acting MAPs—have provided similar results. In a 2011 B4U-ACT survey, nearly one-half of participants reported suicidal ideation due to their minor attraction, 32% had planned suicide attempts, and 13% had non-fatal suicide attempts. Notably, the age group with the most prevalent suicidal ideation was age 14 to 16 years,14 which makes minor attraction a prominent risk factor for suicidal ideation among patients seen by child psychiatrists.

A 2019 thematic analysis of 5,210 posts on the Virtuous Pedophiles website showed high rates of addiction, anxiety, depression, self-harm, self-hatred, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among MAPs.2 The majority of posts regarding substance use described such use as a means of dissociation. One post read, “…There are days I cannot bear to be sober … I … drink myself into a coma.” Anxiety themes regarding the ability to have a meaningful relationship with an age-appropriate partner and concerns about being “outed” followed by public persecution were prominent. Posts regarding self-injurious and suicidal behavior were common: “I want to kill myself so badly … I have to mutilate myself as punishment for my attractions. I wish myself dead. I don’t want to be attracted to children; I despise myself for fantasizing about them.”2

A study that analyzed a survey of 152 MAPs sampled from websites such as Virtuous Pedophiles and others showed >50% of respondents had strong feelings of isolation and loneliness, nearly 30% had extreme difficulty with concentration, >40% had significant anger and frustration, and >30% were struggling with feelings of detachment.12 Notably, the respondents attributed these difficulties to their minor attraction.12 Table 22,12-14 summarizes the findings of studies evaluating psychiatric symptoms in MAPs.

Consider OCD, hypersexuality

It is important to be aware that an attraction to minors may be a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or hypersexuality.15 Pedophilia-themed OCD (POCD) is a manifestation of OCD in which the individual experiences shame, fear, and excessive worry related to sexual attraction to children. Typically, individuals with POCD experience sexual thoughts of children as ego-dystonic, whereas MAPs experience such thoughts as ego-syntonic and arousing.15 However, much like individuals with POCD, MAPs also experience sexual thoughts of minors as distressing. Initial presentations of POCD may be confused with MAPs or pedophilia because of the overlap of symptoms such as anxiety, shame, distress, or suicidal ideation related to the idea of child sexual interests. The distinguishing feature of POCD is the absence of sexual arousal to children.

Continue to: Clinical presentations of...

Clinical presentations of hypersexuality may include sexual arousal to children. These individuals are distinguished from MAPs or those with pedophilia because they lack a preferred or sustained sexual interest in this group. On the contrary, individuals with hypersexuality present with a diversity of sexual interests explained by their high libido. Some individuals, however, may meet criteria for both hypersexuality and pedophilia. These individuals may pose a higher risk of sexual offending due to the presence of a heightened sexual drive and pedophilic interests, and thereby may require more intensive treatment, such as biologic treatment.

Focus on individualized treatment needs

Understanding the treatment needs of MAPs means understanding the goals of the individual MAP. Improving self-esteem, decreasing social isolation, and managing stigma are common treatment goals among MAPs.16 Levenson and Grady12 found that most MAPs identified treatment goals unrelated to sexual interests, such as addressing depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem. A smaller percentage identified sexual frustration related to the absence of healthy sexual outlets. Because many MAPs identify common psychiatric treatment needs, most clinicians should be equipped to foster a nonjudgmental therapeutic alliance to treat these patients. Effective treatment outcomes occur when comorbid psychiatric illnesses are treated as well as addressing the internal stigmatization that many MAPs experience.

Specialized treatment may be indicated for individuals who request treatment specific to sexual interests. This may include safety planning, including developing support systems to decrease the risk around children. For MAPs who have been unsuccessful at managing their sexual interests, pharmacotherapy may be an option. To date, research on pharmacotherapy for pedophilia is largely limited to studies of sexual offenders. Testosterone-lowering medications such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue treatment constitutes the most effective treatment for patients who are not helped by conventional psychotherapeutic interventions.17 Other psychotropic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or naltrexone, have not demonstrated efficacy outside of case reports.17

Addressing barriers to care

MAPs have a strong desire but significant hesitation when seeking mental health treatment.13,18 Nearly half (47%) of the 154 MAP respondents in the Levenson and Grady12 survey had never told anyone about their minor attraction. MAPs are understandably hesitant to disclose these thoughts and feelings due to fear of public exposure and intense stigmatization, as well as potential punitive and legal consequences.18,19 One post from the 2011 B4U-ACT online survey read, “Parents will disown you; teachers will report you; friends will abandon you … people in my situation can’t discuss this without serious risk of persecution and/or harassment.”14 In this survey, 78% of respondents feared a negative reaction by the professional, 78% feared being reported to law enforcement, and 68% feared being reported to family, an employer, or the community.14 This hesitancy due to fear of being exposed even extended to accessing self-help books, informational websites, and online forums, even though these sources are strongly desired and perceived as helpful.20

Even if MAPs were to decide to seek help, the lack of specific training and experience among psychiatrists make them unlikely to find it in the medical field.21 Furthermore, MAPs who desire help often worry it will be inadequate and they will be misunderstood by their clinicians.22 According to the Levenson and Grady survey,12 when asked what they would like most from therapy, most MAPs said they would want the treatment to focus on depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem rather than on sexual interest. In the B4U-ACT survey,14 many respondents identified the need for treatment of issues surrounding their sexual attraction, such as assistance in learning how to live in society with the attraction, dealing with society’s negative response to the attraction, and improving their self-concept in the presence of the extreme shame associated with the attraction. However, many MAPs find that clinicians tend to focus on protecting society from them, rather than on offering general psychiatric treatment or treatment focused on improving their well-being.18 This inability to locate appropriate services is known to exacerbate depression, suicidality, fear, anxiety, hopelessness, and substance abuse among MAPs.18 There is also evidence that individuals with minor attraction who are in a negative affective state are more likely to act on their attractions.23

Continue to: An ethical responsibility

An ethical responsibility. Physicians have a long-recognized responsibility to participate in activities to protect and promote the health of the public. The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics includes “justice,” or treating patients fairly and equitably.24 This includes patients who have pedophilic interests. Unfortunately, the stigma associated with individuals who have sexual attraction to children is pervasive in our society, including among medical professionals. The first consideration in treating MAPs is to overcome the stigmatization within our field, to remember that as physicians we took an oath to provide treatment fairly, equitably, and in accordance with the patient’s rights and entitlement.24 This includes listening to MAPs’ treatment needs. Not all MAPs want or need treatment related to their sexual interest. As is the case with all patients, listening to the individual’s chief complaint is paramount. If a patient’s treatment needs are beyond the clinician’s expertise, the patient should be referred to another clinician.

Mandated reporting. MAPs may not engage in psychiatric treatment for fear of being reported to authorities as a result of mandated reporting laws. Although the circumstances under which mandated reporting may be required vary by jurisdiction, they generally include situations in which the health care professional has reasonable cause to believe that a child is suffering from abuse or neglect. A patient’s report of sexual urges and fantasies to have sexual contact with minors is not sufficient for mandated reporting. While professionals vary in their interpretation of mandated reporting laws, sexual thoughts alone do not meet the threshold for mandated reporting. Mandated reporting duties should be discussed when first meeting a patient with minor attraction. For clinicians who are uneasy about such distinctions, either supervision or not working with such patients is the solution.

The importance of providing competent and individualized treatment to MAPs is 2-fold. First, individuals who are experiencing psychiatric symptoms deserve to have access treatment. Second, providing psychiatric treatment to individuals with minor attractions is a step toward preventing child sexual abuse. The Prevention Project Dunkelfeld in Germany used public service announcements to advertise confidential treatment for individuals who had sexual interest in children.25 Many of the participants were interested in mental health treatment unrelated to their sexual interests. Such projects may help us understand the best way to meet the treatment needs of minor-attracted individuals, as well as reduce child sexual abuse. As psychiatrists, we can stop making the problem worse by withholding psychiatric treatment from an important population.

Resources for MAPs and clinicians

Currently, resources for MAPs and clinicians are limited. MAPs can communicate and find support among other MAPs in online forums (see Related Resources). These websites provide online peer support groups and guides for seeking therapy. Information for mental health professionals, including available literature, research projects, clinicians who provide specialized treatment, and a monthly “dialog on therapy” can be found on the B4U-ACT and the Global Prevention Project websites. However, beyond the DSM-5 definitions, psychiatric education and training on this topic is almost entirely lacking.

In light of the information discussed in this article, several important issues remain, including how psychiatrists can best reach this population, and how they can work toward decreasing stigma so they can provide meaningful care. The solutions start with education. Educating psychiatrists about this important population can decrease stigma and facilitate appropriate, compassionate care to these patients, with the result of improving the mental health of people with minor attraction and decreasing the incidence of child sexual abuse.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Minor-attracted persons report a high prevalence of general psychiatric symptoms that often go untreated due to a lack of willing clinicians with appropriate expertise. Providing psychiatric treatment to these patients can improve their mental health and possibly decrease the incidence of individuals who act on their attractions.

Related Resources

- B4U-ACT. www.b4uact.org • The Global Prevention Project. http://theglobalprevention project.org

- Virtuous Pedophiles. www.virped.org

Drug Brand Names

Naltrexone • ReVia

1. Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(10):1205-1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008

2. Stevens E, Wood J. “I despise myself for thinking about them.” A thematic analysis of the mental health implications and employed coping mechanisms of self-reported non-offending minor attracted persons. J Child Sex Abus. 2019;28(8):968-989. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1657539

3. Sorrentino R. Normal human sexuality and sexual and gender identity disorders: paraphilias. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruis P, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2012:2093-2094.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:685-705.

5. Dombert B, Schmidt AF, Banse R, et al. How common is men’s self-reported sexual interest in prepubescent children? J Sex Res. 2016;53(2):214-23. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1020108

6. Seto MC. Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: theory, assessment, and intervention. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; 2018.

7. Ahlers CJ, Schaefer GA, Mundt IA, et al. How unusual are the contents of paraphilias? Paraphilia-associated sexual arousal patterns in a community-based sample of men. J Sex Med. 2011;8(5):1362-1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01597.x

8. Corrigan PW, Roe D, Tsang HWH. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: lessons for therapists and advocates. Wiley Blackwell; 2011:55-114.

9. Lievesley R, Harper CA, Elliott H. The internalization of social stigma among minor-attracted persons: implications for treatment. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(4):1291-1304. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01569-x

10. Jahnke S, Imhoff R, Hoyer J. Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: two comparative surveys. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(1):21-34. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0312-4

11. Grady MD, Levenson JS, Mesias G, et al. “‘I can’t talk about that”: Stigma and fear as barriers to preventative services for minor-attracted persons. Stigma and Health. 2019;4(4):400-410. doi: 10.1037/sah0000154

12. Levenson JS, Grady MD. Preventing sexual abuse: perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sex Abuse. 2019;31(8):991-1013. doi: 10.1177/1079063218797713

13. Cohen L, Ndukwe N, Yaseen Z, et al. Comparison of self-identified minor-attracted persons who have and have not successfully refrained from sexual activity with children. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44(3):217-230. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1377129

14. B4U-ACT. Awareness of sexuality in youth, suicidality, and seeking care. 2011. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/research/survey-results/spring-2011-survey

15. Bruce SL, Ching THW, Williams MT. Pedophilia-themed obsessive-compulsive disorder: assessment, differential diagnosis, and treatment with exposure and response prevention. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(2):389-402. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1031-4

16. Levenson JS, Grady MD, Morin JW. Beyond the “ick factor”: counseling non-offending persons with pedophilia. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2020;48:380-388. doi: 10.007/s10615-019-00712-4

1 7. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1744723

18. B4U-ACT. Principles and perspectives of practice. 2017. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/about-us/principles-and-perspectives-of-practice/

19. McPhail IV, Stephens S, Heasman A. Legal and ethical issues in treating clients with pedohebephilic interests. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2018;59(4):369-381. doi:10.1037/cap0000157

20. Levenson JS, Willis GM, Vicencio CP. Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: implications for prevention of sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(2):99-120. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116

21. Sorrentino R. DSM-5 and paraphilias: what psychiatrists need to know. Psychiatric Times. November 28, 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/dsm-5-and-paraphilias-what-psychiatrists-need-know

22. Cantor JM, McPhail IV. Non-offending pedophiles. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2016;8:121-128. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0076-z

23. Ward T, Louden K, Hudson SM, et al. A descriptive model of the offense chain for child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10(4):452-472. doi:10.1177/088626095010004005

24. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/principles-of-medical-ethics.pdf

25. Beier KM, Grundmann D, Kuhle LF, et al. The German Dunkelfeld project: a pilot study to prevent child sexual abuse and the use of child abusive images. J Sex Med. 2015;12(2):529-42. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12785

1. Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(10):1205-1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008

2. Stevens E, Wood J. “I despise myself for thinking about them.” A thematic analysis of the mental health implications and employed coping mechanisms of self-reported non-offending minor attracted persons. J Child Sex Abus. 2019;28(8):968-989. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1657539

3. Sorrentino R. Normal human sexuality and sexual and gender identity disorders: paraphilias. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruis P, eds. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2012:2093-2094.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:685-705.

5. Dombert B, Schmidt AF, Banse R, et al. How common is men’s self-reported sexual interest in prepubescent children? J Sex Res. 2016;53(2):214-23. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1020108

6. Seto MC. Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: theory, assessment, and intervention. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; 2018.

7. Ahlers CJ, Schaefer GA, Mundt IA, et al. How unusual are the contents of paraphilias? Paraphilia-associated sexual arousal patterns in a community-based sample of men. J Sex Med. 2011;8(5):1362-1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01597.x

8. Corrigan PW, Roe D, Tsang HWH. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: lessons for therapists and advocates. Wiley Blackwell; 2011:55-114.

9. Lievesley R, Harper CA, Elliott H. The internalization of social stigma among minor-attracted persons: implications for treatment. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(4):1291-1304. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01569-x

10. Jahnke S, Imhoff R, Hoyer J. Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: two comparative surveys. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(1):21-34. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0312-4

11. Grady MD, Levenson JS, Mesias G, et al. “‘I can’t talk about that”: Stigma and fear as barriers to preventative services for minor-attracted persons. Stigma and Health. 2019;4(4):400-410. doi: 10.1037/sah0000154

12. Levenson JS, Grady MD. Preventing sexual abuse: perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sex Abuse. 2019;31(8):991-1013. doi: 10.1177/1079063218797713

13. Cohen L, Ndukwe N, Yaseen Z, et al. Comparison of self-identified minor-attracted persons who have and have not successfully refrained from sexual activity with children. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44(3):217-230. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1377129

14. B4U-ACT. Awareness of sexuality in youth, suicidality, and seeking care. 2011. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/research/survey-results/spring-2011-survey

15. Bruce SL, Ching THW, Williams MT. Pedophilia-themed obsessive-compulsive disorder: assessment, differential diagnosis, and treatment with exposure and response prevention. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(2):389-402. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1031-4

16. Levenson JS, Grady MD, Morin JW. Beyond the “ick factor”: counseling non-offending persons with pedophilia. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2020;48:380-388. doi: 10.007/s10615-019-00712-4

1 7. Thibaut F, Cosyns P, Fedoroff JP, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Paraphilias. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) 2020 guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of paraphilic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2020;21(6):412-490. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2020.1744723

18. B4U-ACT. Principles and perspectives of practice. 2017. Accessed June 4, 2021. www.b4uact.org/about-us/principles-and-perspectives-of-practice/

19. McPhail IV, Stephens S, Heasman A. Legal and ethical issues in treating clients with pedohebephilic interests. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2018;59(4):369-381. doi:10.1037/cap0000157

20. Levenson JS, Willis GM, Vicencio CP. Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: implications for prevention of sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(2):99-120. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116

21. Sorrentino R. DSM-5 and paraphilias: what psychiatrists need to know. Psychiatric Times. November 28, 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/dsm-5-and-paraphilias-what-psychiatrists-need-know

22. Cantor JM, McPhail IV. Non-offending pedophiles. Current Sexual Health Reports. 2016;8:121-128. doi:10.1007/s11930-016-0076-z

23. Ward T, Louden K, Hudson SM, et al. A descriptive model of the offense chain for child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10(4):452-472. doi:10.1177/088626095010004005

24. American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. 2016. Accessed June 4, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/principles-of-medical-ethics.pdf

25. Beier KM, Grundmann D, Kuhle LF, et al. The German Dunkelfeld project: a pilot study to prevent child sexual abuse and the use of child abusive images. J Sex Med. 2015;12(2):529-42. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12785