User login

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

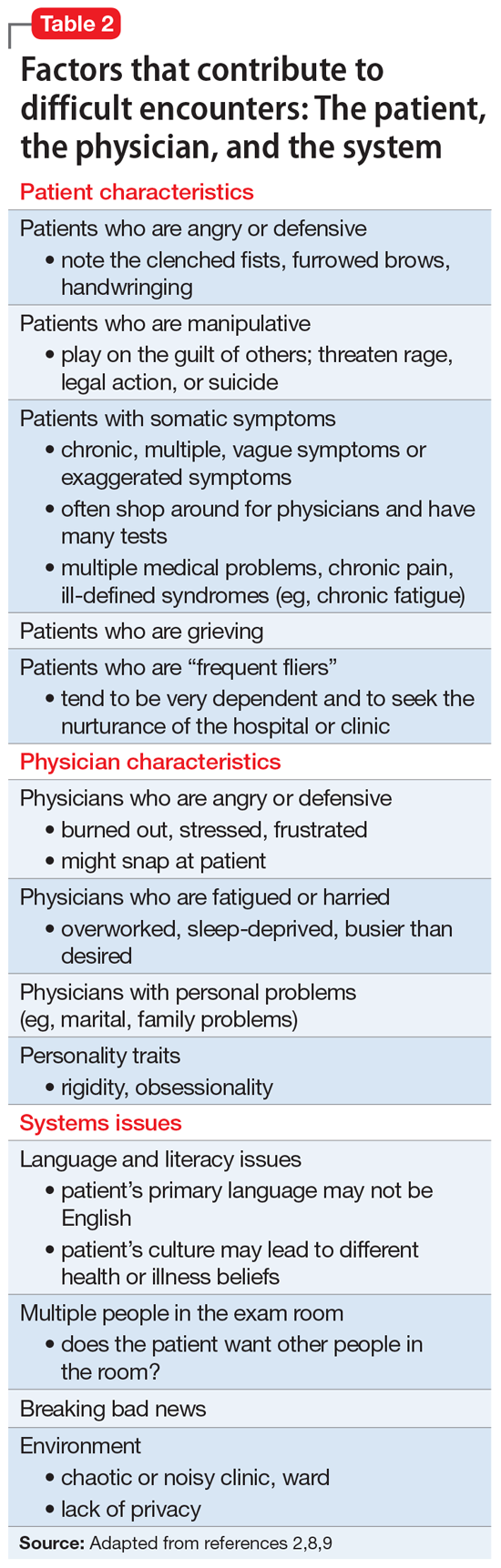

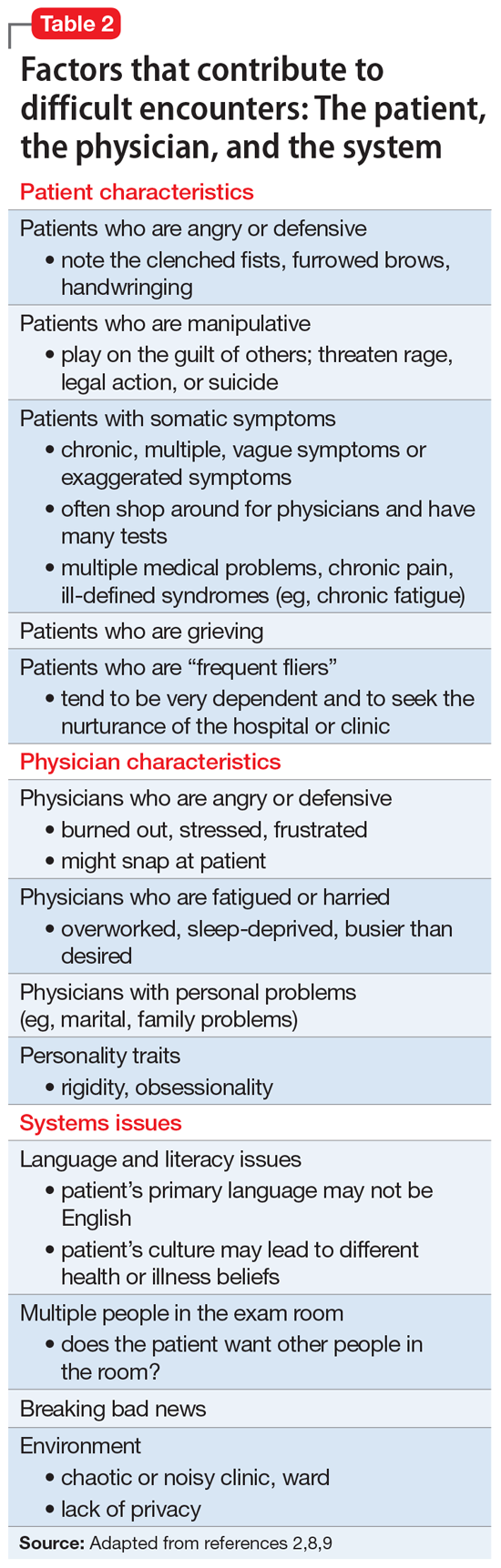

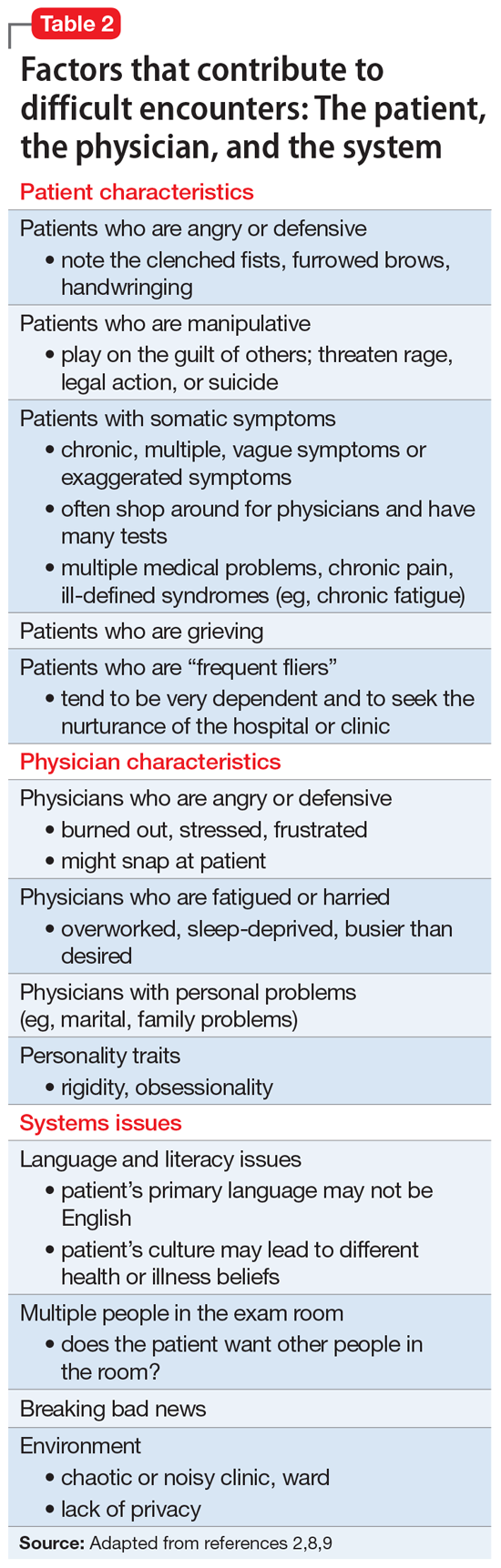

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

“I did not like those patients… They made me angry and I found myself irritated to experience them as they seemed so distant from myself and from all that is human. This is an astonishing intolerance which brands me a poor psychiatrist.”

Sigmund Freud, Letter to István Hollós (1928)

While Freud was referring to psychotic patients,1 his evident frustration shows that difficult and challenging patients have vexed even the best of us. All physicians and other clinicians will experience patient encounters that lead to anger or frustration, or even challenge their sense of equanimity and professional identity. In short, difficult and challenging patient interactions are unavoidable, regardless of the physician’s discipline.2-5 At times, physicians might struggle with demanding, unpleasant, ungrateful, and possibly dangerous patients, while sometimes the struggle is with the patient’s family members. No physician is immune to the problem, which makes it crucial to learn to anticipate and manage difficult patient interactions, skills which are generally not taught in medical schools or residency programs.

One prospective study of clinic patients found that up to 15% of patient encounters are deemed “difficult.”6 Common scenarios include patients (or their relatives) who seek certain tests after researching symptoms online, threats of legal or social media action in response to feeling that the physician is not listening to them, demands for a second opinion after disagreeing with the physician’s diagnosis, and mistrust of doctors after presenting with symptoms and not receiving a diagnosis. It is also common to care for patients who focus on negative outcomes or fail to adhere to treatment recommendations. These encounters can make physicians feel stressed out, disrespected, abused, or even fearful if threatened. Some physicians may come to feel they are trapped in a hostile work environment with little support from their supervisors or administrators. Patients often have a complaint office or department to turn to, but there is no equivalent for physicians, who are expected to soldier on regardless.

This article highlights a model that describes poor physician-patient encounters, factors contributing to these issues, how to manage these difficult interactions, and what to do if the relationship cannot be remediated.

Describing the ‘difficult’ patient

In a landmark 1978 paper, Groves7 provided one of the first descriptions of “difficult” patients. His colorful observations continue to provide useful insights. Groves emphasized that most medical texts ignore the issue of difficult patients and provide little or no guidance—which is still true 43 years later. He observed that physicians cannot avoid occasional negative feelings toward some patients. Further, Groves suggested that countertransference is often at the root of hateful reactions, a process he defines as “conscious or unconscious unbidden and unwanted hostile or sexual feelings toward the patient.”7Table 17 outlines how Groves divided “hateful” patients into several categories, and how physicians might respond to such patients.

A model for understanding difficult patient encounters

Adams and Murray2 created a model to help explain interactions with difficult or challenging patients that consists of 3 elements: the patient, the physician, and the system (ie, situation or environment). Hull and Broquet8 and Hardavella et al9 later adapted the model and described its components (Table 22,8,9).

Continue to: When considering...

When considering difficult interactions, it is important to be aware that all 3 components could interact, or merely 1 or 2 could come into play, but all should be explored as possible contributing factors.

Patient factors

The patient’s role in initiating or maintaining a problematic interaction should be explored. While some physicians are tempted to conclude that a personality disorder underlies difficult interactions, research shows a more complex picture. First, not all difficult patients have a psychiatric disorder, let alone a personality disorder. Jackson and Kroenke6 reported that among 74 difficult patients in an ambulatory clinic, 29% had a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder, with 11% experiencing 2 or more disorders. Major depressive disorder was present in 8.4% patients, other depressive disorders in 17.4%, panic disorder in 1.4%, and other anxiety disorders in 14.2%.6 These researchers found that difficult patient interactions were associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder, especially depressive or anxiety disorders, and multiple physical symptoms.

Importantly, difficult patients are not unique to psychiatry, and are found in all medical disciplines and every type of practice situation. Some problematic patients have a substance use disorder, and their difficulty might stem from intoxication, withdrawal, or drug-seeking behaviors. Psychotic disorders can be the source of difficult interactions, typically resulting from the patient’s symptoms (ie, hallucinations, delusions, or bizarre behavior). Physicians tend to be forgiving toward these patients because they understand the extent of the individual’s illness. The same is true for a patient with dementia, who might be disruptive and loud, yet clearly is not in control of their behavior.

Koekkoek et al5 reviewed 94 articles that focused on difficult patients seen in mental health settings. Most patients were male (60% to 68%), and most were age 26 to 32 years. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders and personality disorders were the most frequent, while mood and other disorders were less common. In 1 of the studies reviewed, 6% of psychiatric inpatients were considered difficult. Koekkoek et al5 proposed that there are 3 groups of difficult patients:

- care avoiders: patients with psychosis who lack insight

- care seekers: patients who are chronically ill who have trouble maintaining a steady relationship with their caregivers

- care claimers: patients who do not require long-term care, but need housing, medication, or a “declaration of incompetence.”

Physician factors

Physicians are frequent contributors to bad interactions with their patients.2,7,8 They can become angry or defensive because of burnout, stress, or frustration, which might lead them to snap or otherwise respond inappropriately to their patients. Many physicians are overworked, sleep-deprived, or busier than they would prefer. Personal problems can be preoccupying and contribute to a physician being ill-tempered or distracted (eg, marital or family problems). Some physicians are simply poor communicators and might not understand the need to adapt their communication style to their patient, instead using medical jargon the patient does not understand. Ideally, physicians should modify their language to suit the patient’s level of education, degree of medical sophistication, and cultural background.

Continue to: A physician's personality traits...

A physician’s personality traits could clash with those of the patient, particularly if the physician is especially rigid or obsessional. Rather than “going with the flow,” the overly rigid physician might become impatient with patients who fail to understand diagnostic assessments or treatment recommendations. Inefficient physicians might not be able to keep up with the daily schedule, which could fuel impatience and perhaps even lead them to think that the patient is taking too much of their valuable time. Some might not know how to convey empathy, for example when giving bad news (“The tests show you have cancer…”). Others fail to make consistent eye contact with patients without understanding its importance to communication, a problem made worse by the use of electronic medical record systems (EMRs).

Systems issues

Systems issues also contribute to suboptimal physician-patient interactions, and some issues can be attributed to administrative problems. Examples of systems issues include:

- when a patient has difficulty making an appointment and is forced to listen to a confusing menu of choices

- a busy clinic that can only offer a patient an appointment 6 months away

- crowded or noisy waiting rooms

- language barriers for patients whose primary langage is not English. Not having access to an interpreter can exacerbate their frustration

- the use of EMRs is a growing threat to positive physician-patient interactions, yet their influence is often ignored. Widely disliked by physicians,10 EMRs are required in all but the smallest independent practice settings. Many busy physicians focus their attention on the computer, giving the patient the impression that the physician is not listening to them. Many patients conclude that they are less important than the process.

The consequences of difficult interactions

Following a bad interaction, dissatisfied patients are more likely to leave the clinic or hospital and ignore medical advice. These patients might then show up in crowded emergency departments, which may lead to poor use of health care resources. For physicians, challenging situations sap their emotional energy, cause demoralization, and interfere with their sense of job fulfillment. In extreme cases, such feelings might lead the physician to dislike and even avoid the patient.

How to manage challenging situations

Taking the following steps can help physicians work through challenging situations with their patients.

Diagnose the problem. First, recognize the difficult situation, analyze it, and identify how the patient, the physician, and the system are contributing to a bad physician-patient interaction. Diagnosing the interactional difficulty should precede the diagnosis and management of the patient’s disease. Physicians should acknowledge their own contribution through their attitude or actions. Finally, determine if there are system issues that are contributing to the problem, or if it is the clinic or inpatient setting itself (eg, noisy inpatient unit).

Continue to: Maintain your cool

Maintain your cool. With any difficult interaction, a physician’s first obligation is to remain calm and professional, while modeling appropriate behavior. If the patient is angry or emotionally intense, talking over them or interrupting them only makes the situation worse. Try to see the interaction from the patient’s perspective. Both parties should work together to find a common ground.

Collaborate, respect boundaries, and empathize. One study of a group of 100 family physicians found that having the following 3 skills were essential to successfully managing situations with difficult patients11,12:

- the ability to collaborate (vs opposition)

- the appropriate use of power (vs misuse of power, or violation of boundaries by either party)

- the ability to empathize, which for most physicians involves understanding and validating the patient’s subjective experiences.

Although a description of the many facets of empathy (cognitive, affective, motivational) is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that a patient’s positive perception of their physician’s empathy improves not only patient satisfaction but health outcomes.13 The Box describes a difficult patient whose actions changed through the collaboration and empathy of his treatment team.

Box 1

Mr. L, a 60-year-old veteran, is admitted to an inpatient unit following a suicide attempt that was prompted by eviction from his apartment. Mr. L is physically disabled and has difficulty walking without assistance. His main concern is his homelessness, and he insists that the inpatient team find a suitable “Americans with Disabilities (ADA)-compliant apartment” that he can afford on his $800 monthly income. He implies that he will kill himself if the team fails in that task. He makes it clear that his problems are the team’s problems. He is prescribed an antidepressant, and both his mood and reported suicidal ideations gradually resolve.

The team’s social worker finds an opening at a well-run veterans home, but Mr. L rejects it because he doesn’t want to “give up his independence.” The social worker finds a small apartment in a nearby community that is ADA-compliant, but Mr. L complains that it is small. He asks the resident psychiatrist, “Where will I put all my things?” The next day, after insulting the attending psychiatrist for failing to find an adequate apartment, Mr. L says from under the bedsheet: “How come none of you ever help me?”

Mr. L presents a challenge to the entire team. At times, he is rude, demanding, and entitled. The team recognizes that although he had served in the military with distinction, he is now alone after having divorced many years earlier, and nearly friendless because of his increasing disability. The team surmises that Mr. L lashes out due to frustration and feelings of powerlessness.

Resolving this conflict involves treating Mr. L with respect and listening without judgment. No one ever confronts him or argues with him. The team psychologist meets with him to help him work through his many losses. Closer to discharge, he is enrolled in several post-hospitalization programs to keep him connected with other veterans. At discharge, the hospital arranges for his belongings that had been in storage to be delivered to his new home. He is pleasant and social with his peers, and although he is still concerned about the size of the apartment, he thanks the team members for their care.

Verbalize the difficulty. It is important to openly discuss the problem. For example, “We both have very different views about how your symptoms should be investigated, and that’s causing some difficulty between us. Do you agree?” This approach names the “elephant in the room” and avoids casting blame. It also creates a sense of shared ownership by externalizing the problem from both the patient and physician. Verbalizing the difficulty can help build trust and pave the way to working together toward a common solution.

Consider other explanations for the patient’s behavior. For example, anger directed at a physician could be due to anxiety about an unrelated matter, such as the patient’s recent job loss or impending divorce. Psychiatrists might understand this behavior better as displacement, which is considered a maladaptive defense mechanism. It is important to listen to the patient and offer empathy, which will help the patient feel supported and build a rapport that can help to resolve the encounter.

Continue to: When helping patients...

When helping patients with multiple issues, which is a common scenario, the physician might start by asking, “What would you like to address today?”14 Keep a list of the issues so you do not forget the patient’s concerns, and then ask: “What do you think is going on?” Give patients time to verbalize their concerns. Physicians should:

- validate concerns: “I understand where you’re coming from.”

- offer empathy: “I can see how difficult this has been for you.”

- reframe: “Let me make sure I hear you correctly.”

- refocus: “Let’s agree on what we need to do at this visit.”

Find common ground. When the patient and physician have different ideas on diagnosis or treatment, finding common ground is another way to resolve a difficult encounter. Difficulties arise when there appears to be little common ground, which often results from unrealistic expectations. Patients might be seen as “demanding” or “manipulative”’ if they push for a diagnosis or treatment the doctor is not comfortable with. As soon as there is some overlap and common ground, the difficulty rapidly subsides.

Set clear boundaries and limits. Physicians should set limits on what patient behavior might “cross the line.” A “behavioral contract” (or “treatment contract”) can help by setting explicit expectations. For example, showing up late for appointments or inappropriately seeking drugs of abuse (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines) might be identified as violations of the contract. Once the contract is set, the patient should be asked to restate key components. Clarify any confusion or barriers to compliance and define clear expectations. The patient should be informed of potential consequences of contract violations, including termination.

Staff members involved in the patient’s care should agree with the terms of any behavioral contract, and should receive a copy of it. Patients should have “buy in,” meaning that they have had an opportunity to provide input to the contract and have agreed to its elements. Both the physician and patient should sign the document.

When all else fails

When there is a breakdown in rapport that makes it difficult or impossible to continue offering treatment, consider termination. This could be due to threatening or abusive patient behavior, sexual advances, repeated no-shows, treatment noncompliance that jeopardizes patient safety, refusal to follow the treatment plan, or violating the terms of a behavioral contract. In some settings, it might be the failure to pay bills.

Continue to: If a patient is unable to...

If a patient is unable to follow the contract, the physician should explore possible extenuating circumstances. The physician should seek to remedy the problem and involve other team members if possible (eg, case manager, nurse), advising a patient about behaviors that could lead to termination.

If the problem is irremediable, notify the patient in writing, give them time to find another physician, and facilitate the transfer of care.15 Take steps to prevent the patient from running out of any medications associated with withdrawal or discontinuation syndromes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines) during the care transition. While there is no requirement regarding the amount of time allowed, at least 30 days is typical.

Bottom Line

Difficult patient interactions are common and unavoidable. Physicians should acknowledge and recognize contributing factors in such encounters—including their own role. When handling such situations, physicians should remain calm and model appropriate behavior. Improving communication, offering empathy, and validating the patient’s concerns can help resolve factors that contribute to poor patient interactions. If efforts to remediate the physician-patient relationship fail, termination may be necessary.

Related Resources

- Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

- Pereira MR, Figueiredo AF. Challenging patient-doctor interactions in psychiatry – difficult patient syndrome. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(supplement):S719. doi. org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1297

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.

1. Dupont J. Ferenczi’s madness. Contemp Psychoanal. 1988;24(2):250-261.

2. Adams J, Murray R. The difficult diagnosis: the general approach to the difficult patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1998;16(4):689-700.

3. Davies M. Managing challenging interactions with patients. BMJ. 2013;347:f4673. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4673

4. Chou C. Dealing with the “difficult” patient. Wisc Med J. 2004;103:35-38.

5. Koekkoek B, Berno van Meijel CNS, Hutschemaekers G. “Difficult patients” in mental health care: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):795-802.

6. Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounter in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(10):1069-1075.

7. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Eng J Med. 1978;298:883-887.

8. Hull S, Broquet K. How to manage difficult encounters. Fam Prac Manag. 2007;14(6):30-34.

9. Hardavella G, Aamli-Gaagnat A, Frille A, et al. Top tips to deal with challenging situations: doctor patient interactions. Breathe. 2017;13(2):129-135.

10. Black DW, Balon R. Editorial: electronic medical records (EMRs) and the psychiatrist shortage. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):257-259.

11. Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(6):533-541.

12. Campbell RJ. Campbell’s Psychiatric Dictionary. 8th Edition. Oxford University Press; 2004:219-220.

13. Decety J, Fotopoulou A. Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: unifying theories. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457

14. Klugman B. The difficult patient. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/office-of-continuing-medical-education/pdfs/cme-primary-care-days/e2-the-difficult-patient.pdf

15. Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. ‘Firing’ a patient: may psychiatrists unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18-29.