User login

‘Immediately after the event I was a wreck. I vaguely remember talking to the family; I don’t know if I was much use to them. … That night I got drunk. It was the only way I could sleep. A sensitive colleague came and sat with me.”1

Besides being targets of malpractice suits, psychiatrists also serve as resources for colleagues who are sued. Specific actions can help you and those you counsel deal with the stress of an adverse event before and during litigation. Remember that:

- anticipation is the best defense

- knowledge is power

- action counters passivity

- a supportive environment is essential.

ANTICIPATING LITIGATION

What is the risk? No nationwide reporting system tracks the incidence of medical malpractice claims, but industry experts suggest a claim is leveled against 7% of psychiatrists each year.2 The risk is higher for other medical specialists: a recent survey by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists found that 89% of practicing ObGyns had been sued at least once in their careers.3 Because a claim usually takes several years to resolve, a substantial number of physicians—including psychiatrists—are involved in litigation at any one time.

Successfully anticipating litigation begins with being familiar with your state’s statute of limitations—usually 2 to 3 years after discovery of the incident, with exceptions for children, the disabled, and designated special circumstances. If a plaintiff’s case is not filed within this time, a disputed outcome can never be the subject of a malpractice claim.

Adverse events. The severity of the outcome, the nature of your relationship with the patient, and the degree of your responsibility for an adverse event contribute to the intensity of your initial emotional response. If a mistake caused the event, your reaction may be even more severe.4-6 Whatever the event’s specifics, you may ruminate about your role and degree of responsibility (Table 1).

Table 1

Nagging questions after a ‘bad’ patient outcome

|

Expect that your view of the circumstances will generate a complex array of feelings: shock, anxiety, depression, shame, guilt, self-blame, disbelief, self-doubt and inadequacy, anger, and even relief from not having to work with a difficult patient anymore.

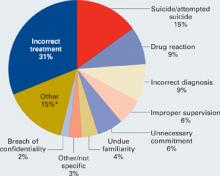

Patient suicide. More than one-half of psychiatrists and up to one-third of psychiatric residents experience a patient suicide.7-10 The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations reports that suicide is the most frequent sentinel event, representing 501 (13.1%) of the total 3,811 sentinel events reviewed since 1995.11 Professional Risk Management Services, a major medical malpractice insurer of psychiatrists, reports that suicide and attempted suicide are the most frequently identifiable causes of liability payments (Figure).

Figure 1 Psychiatric claims by cause of loss in the United States, 1998 to 2005

Almost all lawsuits assert multiple allegations of negligence, and “cause of loss” represents the main allegation made in the claim or lawsuit. Thus, the category of “incorrect treatment” may be alleged in a lawsuit based on a patient suicide, but the main or chief allegation/complaint is stated as “incorrect treatment.” The most frequent identifiable cause of loss is suicide and attempted suicide.

* “Other” includes administrative issues, abandonment, premises liability, Tarasoff, third parties (such as parents), retained object, libel/slander, boundary violation, deleted duplicate file, Fen-phen, lack of informed consent, forensic issues, and miscellaneous.

Source: Prepared by Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

Psychiatrists’ feelings of distress after a patient suicide mirror the personal sense of failure and inadequacy most physicians feel when they are unable to prevent a patient’s death or serious injury. At the same time, we must:

- deal with the event’s medical complications, with relevant notifications and disclosures (Table 2)

- address the emotional pain of the injured patient or family

- participate in mandated reviews

- recognize and manage our emotional disruption (Table 3).

Table 2

Recommended medical steps, notifications,

and disclosures after an adverse event

| MEDICAL STEPS Take necessary actions to limit further injury or disability Obtain appropriate consultations Review the medical record; anticipate the patient’s follow-up needs and make recommendations for further treatment |

| NOTIFICATIONS Follow the health care system’s and insurer’s guidelines for notifying the patient/family Inform the institution’s risk manager and your professional liability carrier as soon as possible Write a description of the event for the record and a narrative for your personal file (and your lawyer’s) in case a suit is filed later Do not talk with the media |

| DISCLOSURES Acknowledge your ethical obligation to be truthful Follow your institution’s and insurer’s disclosure guidelines Expect to feel intimidated and uneasy in discussing your role in the event Expect the patient/family to be angry and disappointed in you Convey an interest in the patient’s/family’s emotional state; express sorrow for their loss Tell the patient/family what you know for sure; don’t speculate about what is not known, and don’t make false promises or false reassurances Don’t hurry; give the patient/family time to ask questions Expect to feel better after a truthful exchange |

Table 3

Managing your emotions before and during litigation

| Anticipate having repeated thoughts and preoccupations about the event; work toward a realistic view of it |

| Recognize your feelings and work to understand their source |

| Talk with a trusted confidant (your spouse, colleague, etc.) about your feelings |

| Monitor your emotional and physical status and, if indicated, seek appropriate consultation |

| Avoid situations that generate anxiety and increase stress |

| Monitor and address changes in relationships with family, patients, colleagues, and staff |

| Be understanding of yourself and others; develop a realistic view of yourself as a ‘good doctor’ |

| Engage in active sports and take regular vacations unrelated to professional activities |

| Control what can be controlled |

Self-evaluation. To cope with distress when a patient dies, you could attend the funeral. If the death was by suicide, consider consulting with a therapist about your reactions or review the case with your supervisor. You also might:

- make changes in your practice that alert you to problem patients

- introduce a more structured approach to patients with particular clinical conditions, using practice guidelines as a resource12,13

- become more alert to patients who may benefit from consultation or referral.

Balance the time you devote to work and personal life. Schedule regular time for recreation and active sports, which can help you prepare for the prolonged stress that follows being sued. Engage a personal physician to monitor your physical and emotional health and to recommend appropriate referrals when indicated.

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER

What can I expect? A lawsuit generates a mixture of common emotions and exacerbates those felt at the time of the bad outcome: shock, outrage, anxiety, anguish, dread, depression, helplessness, hopelessness, feelings of being misunderstood, and the anger and vulnerability associated with a narcissistic injury. As one ObGyn stated, learning that a lawsuit was filed “just prolonged my misery.”14

Each of us reacts in our own way to a lawsuit—and differently to each lawsuit if we are sued more than once—because of:

- our personality traits and personal circumstances

- the specifics of each case

- our relationship with the patient

- the public nature of a lawsuit

- a range of other variables that makes each case unique.

Suddenly, we who perceive ourselves as caring, beneficent, well-meaning, and devoted to our patients are publicly accused of being careless and incompetent, of harming the patient by failing to meet our minimal obligations. Psychiatrists Richard Ferrell and Trevor Price15 capture the impact of these allegations:

"Here are the sense of assault and violation, the feelings of outrage and fear. Most painfully, here is the narcissistic injury, the astonishing wound to our understanding of ourselves as admirable, well-meaning people."

Litigation is a lengthy process with defined stages (Table 4). We have little control over a slow-paced process that involves an array of participants (lawyers, judges, jury, and experts) whose behavior is not predictable. This makes us feel dependent, vulnerable, and impotent.

Table 4

Stages of litigation: What happens in court

| Stage | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Summons | Notification that a suit has been filed |

| Complaint | The nature of the allegation in legal terms |

| Pleadings | The attorney begins to communicate with the court by filing motions, a request that the court do something |

| Discovery | A process designed to obtain information about the case:

|

| Summary judgment | A motion asking the court, after the facts have been established by discovery, to decide the validity of the case; if granted, the case is resolved without a trial by jury |

| Settlement | An agreement between parties that resolves their legal dispute |

| Trial | Case is presented to the judge or a judge and jury to determine culpability |

| Verdict | Decision reached by the deciding body |

| Post-trial | If the defendant receives an unfavorable verdict, motions may be offered to the court to void or appeal the verdict |

BE ACTIVE, NOT PASSIVE

What you can do. Contact your insurer and risk manager immediately. Inquire about the average length of litigation in your jurisdiction (might be 1 to 5 or more years, depending on locality, type of case, and severity of injury). Ask your lawyer to describe the steps in the process and your role as the case proceeds.

Take whatever steps are necessary to cover your clinical duties. If your initial emotional reaction is disruptive, obtain coverage or rearrange your schedule. Expect to change or limit your schedule before depositions and during trial to allow adequate time for preparation.

Accept the fact that you must play by rules far different from those of medical care. Litigation is time-consuming and frustrating. Delays and “continuances” are common in legal proceedings, so expect them. Consider adapting to your own situation strategies that other sued physicians have found useful in regaining control over their lives and work (Table 5).

Table 5

Regaining control: Managing your practice during litigation

| Learn as much as you can about the legal process |

| Introduce good risk management strategies, such as efficient record-keeping, into your practice |

| Clarify the responsibilities of office personnel and coverage responsibilities with associates |

| Rearrange office schedules during periods of increased stress |

| Re-evaluate your time commitments to work and family |

| Participate in relevant continuing education |

| Make sure your financial and estate planning is current |

| Cooperate with legal counsel |

| Devote sufficient time to deposition preparation and other demands of the case |

| Carefully evaluate the advice of legal and insurance counsel regarding a settlement |

| Do not try to “fit patients in” while on trial; trial is a full-time job |

GET NEEDED SUPPORT

Talking about the case. Sharing with responsible confidants your emotional reactions to being sued is healthy for you and others affected. Lawyers, however, may caution you not to “talk to anybody” about the case. They don’t want you to say anything that would suggest liability or jeopardize their defense of the case.

As psychiatrists, we know this is not good psychological advice. The support of others is a natural help during major life events that cause enormous stress and disruption.16 You can resolve this dilemma by accepting the discipline of talking about your feelings regarding the case without discussing the specifics of the case.

In addition to lawyers and claims representatives, you may talk with your spouse or another trusted person or colleague about your feelings. When other physicians or psychiatrists formally consult with you about their litigation experiences, you are protected by the confidentiality inherent in the doctor-patient relationship.

Trust issues. Trust lies at the core of psychotherapeutic work. After being sued, you may find it difficult to re-establish trusting and comfortable relationships with patients, especially those who are seriously ill.

Well-trained, competent physicians who keep current with standards of care and have good relationships with patients do not expect to be sued. Psychiatrists often feel unrealistically immune to litigation because we believe our training helps us understand our own psychology and relationships with others. A charge of negligence exposes our vulnerabilities and leaves us feeling hurt and betrayed. As one psychiatrist ruefully observed, “I lost my innocence.”14

Countertransference feelings may emerge. Most physicians acknowledge that after being sued their relationships with patients change17,18—a particularly distressing outcome for psychiatrists. We may feel uncomfortable and threatened when we need to “stretch the patient-doctor relationship in a paternalistic direction,” such as when a psychotic patient needs involuntary commitment.15

Feelings that you must change the way you practice and chronic anxiety about your work are barriers to good practice. You may contemplate changing practice circumstances or retiring early. Personal therapy may help if you remain uneasy or cannot resolve life choices that overshadow your work with patients.

Medical or psychiatric care. Be alert to the point at which you or others involved in litigation need a referral for medical or psychiatric consultation. Sued physicians, their families, or colleagues often experience diagnosable psychiatric conditions or other behavioral problems, such as:

- major depression

- adjustment disorders

- posttraumatic stress disorder

- worsening of a previously diagnosed psychiatric illness

- physical symptoms that require diagnosis and treatment

- alcohol and drug misuse or abuse

- anxiety and distress that interfere with work

- self-medication, especially for insomnia

- disturbances and dysfunctional behaviors that affect marital and family life.19,20

SUPPORT YOUR COLLEAGUES

When consulting with other physicians, be aware of litigation factors that may influence treatment.

Become familiar with the climate of litigation in the jurisdiction where the case was filed, including the incidence and outcome of cases. For example, does an attempted suicide case usually result in settlement or—if it goes to trial—take 2 to 5 or more years to resolve? More than 70% of cases filed nationwide result in no payment (no settlement) for the plaintiff. If cases go to trial, physicians win 80% of the time.21

Recognize that the source of the physician’s distress may be the trauma associated with the initial bad outcome, rather than the malpractice suit itself. As the case progresses and facts emerge, you may play a large role in helping your physician patient correct previous distortions of the event. Certain periods—during trial, for example—might require more-frequent visits, medication, and expressions of support.

You may harbor a bias about the case, but withhold judgment until it is resolved.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. From exam room to court room: navigating litigation and coping with stress (CD-ROM) http://sales.acog.com/acb/stores/1/product1.cfm?SID=1&Product_ID=589).

- Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Physician Litigation Stress Resource Center. www.physicianlitigationstress.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Charles reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Anonymous. Looking back… BMJ 2000;320(7237):812.-

2. Martin G, Tracy JD. President and CEO, Professional Risk Management Services. Personal communication. October 20, 2006.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG 2006 Professional Liability Survey. Washington, DC; 2006. Available at: http://www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=4&bulletin=3963. Accessed January 16, 2007.

4. Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med 1992;7(4):424-31.

5. Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320(7237):726-7.

6. Aasland OG, Forde R. Impact of feeling responsible for adverse events on doctors’ personal and professional lives: the importance of being open to criticism from colleagues. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2005;14:13-7.

7. Alexander DA, Klein S, Grey NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ 2000;320:1571-4.

8. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

9. Brown HN. The impact of suicide on therapists in training. Compr Psychiatry 1987;28:101-12.

10. Ellis TE, Dickey TO, Jones EC. Patient suicide in psychiatric residency programs: a national survey of training and postvention practices. Academic Psychiatry 1998;22:181-9.

11. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel event statistics. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/74540565-4D0F-4992-863E-8F9E949E6B56/0/se_stats_6_30_06.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2006.

12. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157(12):2022-7.

13. Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders (compendium 2006) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

14. Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:94,120.

15. Ferrell RB, Price TRP. Effects of malpractice suits on physicians. In: Gold JH, Nemiah JC, eds. Beyond transference. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993:141-58.

16. Watson PJ, Friedman MJ, Gibson LE, et al. Early intervention in trauma-related problems. In: Ursano R, Norwood AE, eds. Trauma and disaster: responses and management. Review of psychiatry vol. 22. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:100-1.

17. Charles SC, Psykoty CE, Nelson A. Physicians on trial—self-reported reactions to malpractice trials. West J Med 1988;148:358-60.

18. Charles SC. The doctor-patient relationship and medical malpractice litigation. Bull Menninger Clin 1993;57(2):195-207.

19. Charles SC, Wilbert JR, Franke KJ. Sued and non-sued physicians’ self-reported reactions to malpractice litigation. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:437-40.

20. Martin CA, Wilson JA, Fiebelman ND, et al. Physicians’ psychologic reactions to malpractice litigation. South Med J 1991;84:1300-4.

21. Outcome of closed medical malpractice claims. National data (1985-2005). Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA). Rockville, MD; 2006.

‘Immediately after the event I was a wreck. I vaguely remember talking to the family; I don’t know if I was much use to them. … That night I got drunk. It was the only way I could sleep. A sensitive colleague came and sat with me.”1

Besides being targets of malpractice suits, psychiatrists also serve as resources for colleagues who are sued. Specific actions can help you and those you counsel deal with the stress of an adverse event before and during litigation. Remember that:

- anticipation is the best defense

- knowledge is power

- action counters passivity

- a supportive environment is essential.

ANTICIPATING LITIGATION

What is the risk? No nationwide reporting system tracks the incidence of medical malpractice claims, but industry experts suggest a claim is leveled against 7% of psychiatrists each year.2 The risk is higher for other medical specialists: a recent survey by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists found that 89% of practicing ObGyns had been sued at least once in their careers.3 Because a claim usually takes several years to resolve, a substantial number of physicians—including psychiatrists—are involved in litigation at any one time.

Successfully anticipating litigation begins with being familiar with your state’s statute of limitations—usually 2 to 3 years after discovery of the incident, with exceptions for children, the disabled, and designated special circumstances. If a plaintiff’s case is not filed within this time, a disputed outcome can never be the subject of a malpractice claim.

Adverse events. The severity of the outcome, the nature of your relationship with the patient, and the degree of your responsibility for an adverse event contribute to the intensity of your initial emotional response. If a mistake caused the event, your reaction may be even more severe.4-6 Whatever the event’s specifics, you may ruminate about your role and degree of responsibility (Table 1).

Table 1

Nagging questions after a ‘bad’ patient outcome

|

Expect that your view of the circumstances will generate a complex array of feelings: shock, anxiety, depression, shame, guilt, self-blame, disbelief, self-doubt and inadequacy, anger, and even relief from not having to work with a difficult patient anymore.

Patient suicide. More than one-half of psychiatrists and up to one-third of psychiatric residents experience a patient suicide.7-10 The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations reports that suicide is the most frequent sentinel event, representing 501 (13.1%) of the total 3,811 sentinel events reviewed since 1995.11 Professional Risk Management Services, a major medical malpractice insurer of psychiatrists, reports that suicide and attempted suicide are the most frequently identifiable causes of liability payments (Figure).

Figure 1 Psychiatric claims by cause of loss in the United States, 1998 to 2005

Almost all lawsuits assert multiple allegations of negligence, and “cause of loss” represents the main allegation made in the claim or lawsuit. Thus, the category of “incorrect treatment” may be alleged in a lawsuit based on a patient suicide, but the main or chief allegation/complaint is stated as “incorrect treatment.” The most frequent identifiable cause of loss is suicide and attempted suicide.

* “Other” includes administrative issues, abandonment, premises liability, Tarasoff, third parties (such as parents), retained object, libel/slander, boundary violation, deleted duplicate file, Fen-phen, lack of informed consent, forensic issues, and miscellaneous.

Source: Prepared by Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

Psychiatrists’ feelings of distress after a patient suicide mirror the personal sense of failure and inadequacy most physicians feel when they are unable to prevent a patient’s death or serious injury. At the same time, we must:

- deal with the event’s medical complications, with relevant notifications and disclosures (Table 2)

- address the emotional pain of the injured patient or family

- participate in mandated reviews

- recognize and manage our emotional disruption (Table 3).

Table 2

Recommended medical steps, notifications,

and disclosures after an adverse event

| MEDICAL STEPS Take necessary actions to limit further injury or disability Obtain appropriate consultations Review the medical record; anticipate the patient’s follow-up needs and make recommendations for further treatment |

| NOTIFICATIONS Follow the health care system’s and insurer’s guidelines for notifying the patient/family Inform the institution’s risk manager and your professional liability carrier as soon as possible Write a description of the event for the record and a narrative for your personal file (and your lawyer’s) in case a suit is filed later Do not talk with the media |

| DISCLOSURES Acknowledge your ethical obligation to be truthful Follow your institution’s and insurer’s disclosure guidelines Expect to feel intimidated and uneasy in discussing your role in the event Expect the patient/family to be angry and disappointed in you Convey an interest in the patient’s/family’s emotional state; express sorrow for their loss Tell the patient/family what you know for sure; don’t speculate about what is not known, and don’t make false promises or false reassurances Don’t hurry; give the patient/family time to ask questions Expect to feel better after a truthful exchange |

Table 3

Managing your emotions before and during litigation

| Anticipate having repeated thoughts and preoccupations about the event; work toward a realistic view of it |

| Recognize your feelings and work to understand their source |

| Talk with a trusted confidant (your spouse, colleague, etc.) about your feelings |

| Monitor your emotional and physical status and, if indicated, seek appropriate consultation |

| Avoid situations that generate anxiety and increase stress |

| Monitor and address changes in relationships with family, patients, colleagues, and staff |

| Be understanding of yourself and others; develop a realistic view of yourself as a ‘good doctor’ |

| Engage in active sports and take regular vacations unrelated to professional activities |

| Control what can be controlled |

Self-evaluation. To cope with distress when a patient dies, you could attend the funeral. If the death was by suicide, consider consulting with a therapist about your reactions or review the case with your supervisor. You also might:

- make changes in your practice that alert you to problem patients

- introduce a more structured approach to patients with particular clinical conditions, using practice guidelines as a resource12,13

- become more alert to patients who may benefit from consultation or referral.

Balance the time you devote to work and personal life. Schedule regular time for recreation and active sports, which can help you prepare for the prolonged stress that follows being sued. Engage a personal physician to monitor your physical and emotional health and to recommend appropriate referrals when indicated.

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER

What can I expect? A lawsuit generates a mixture of common emotions and exacerbates those felt at the time of the bad outcome: shock, outrage, anxiety, anguish, dread, depression, helplessness, hopelessness, feelings of being misunderstood, and the anger and vulnerability associated with a narcissistic injury. As one ObGyn stated, learning that a lawsuit was filed “just prolonged my misery.”14

Each of us reacts in our own way to a lawsuit—and differently to each lawsuit if we are sued more than once—because of:

- our personality traits and personal circumstances

- the specifics of each case

- our relationship with the patient

- the public nature of a lawsuit

- a range of other variables that makes each case unique.

Suddenly, we who perceive ourselves as caring, beneficent, well-meaning, and devoted to our patients are publicly accused of being careless and incompetent, of harming the patient by failing to meet our minimal obligations. Psychiatrists Richard Ferrell and Trevor Price15 capture the impact of these allegations:

"Here are the sense of assault and violation, the feelings of outrage and fear. Most painfully, here is the narcissistic injury, the astonishing wound to our understanding of ourselves as admirable, well-meaning people."

Litigation is a lengthy process with defined stages (Table 4). We have little control over a slow-paced process that involves an array of participants (lawyers, judges, jury, and experts) whose behavior is not predictable. This makes us feel dependent, vulnerable, and impotent.

Table 4

Stages of litigation: What happens in court

| Stage | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Summons | Notification that a suit has been filed |

| Complaint | The nature of the allegation in legal terms |

| Pleadings | The attorney begins to communicate with the court by filing motions, a request that the court do something |

| Discovery | A process designed to obtain information about the case:

|

| Summary judgment | A motion asking the court, after the facts have been established by discovery, to decide the validity of the case; if granted, the case is resolved without a trial by jury |

| Settlement | An agreement between parties that resolves their legal dispute |

| Trial | Case is presented to the judge or a judge and jury to determine culpability |

| Verdict | Decision reached by the deciding body |

| Post-trial | If the defendant receives an unfavorable verdict, motions may be offered to the court to void or appeal the verdict |

BE ACTIVE, NOT PASSIVE

What you can do. Contact your insurer and risk manager immediately. Inquire about the average length of litigation in your jurisdiction (might be 1 to 5 or more years, depending on locality, type of case, and severity of injury). Ask your lawyer to describe the steps in the process and your role as the case proceeds.

Take whatever steps are necessary to cover your clinical duties. If your initial emotional reaction is disruptive, obtain coverage or rearrange your schedule. Expect to change or limit your schedule before depositions and during trial to allow adequate time for preparation.

Accept the fact that you must play by rules far different from those of medical care. Litigation is time-consuming and frustrating. Delays and “continuances” are common in legal proceedings, so expect them. Consider adapting to your own situation strategies that other sued physicians have found useful in regaining control over their lives and work (Table 5).

Table 5

Regaining control: Managing your practice during litigation

| Learn as much as you can about the legal process |

| Introduce good risk management strategies, such as efficient record-keeping, into your practice |

| Clarify the responsibilities of office personnel and coverage responsibilities with associates |

| Rearrange office schedules during periods of increased stress |

| Re-evaluate your time commitments to work and family |

| Participate in relevant continuing education |

| Make sure your financial and estate planning is current |

| Cooperate with legal counsel |

| Devote sufficient time to deposition preparation and other demands of the case |

| Carefully evaluate the advice of legal and insurance counsel regarding a settlement |

| Do not try to “fit patients in” while on trial; trial is a full-time job |

GET NEEDED SUPPORT

Talking about the case. Sharing with responsible confidants your emotional reactions to being sued is healthy for you and others affected. Lawyers, however, may caution you not to “talk to anybody” about the case. They don’t want you to say anything that would suggest liability or jeopardize their defense of the case.

As psychiatrists, we know this is not good psychological advice. The support of others is a natural help during major life events that cause enormous stress and disruption.16 You can resolve this dilemma by accepting the discipline of talking about your feelings regarding the case without discussing the specifics of the case.

In addition to lawyers and claims representatives, you may talk with your spouse or another trusted person or colleague about your feelings. When other physicians or psychiatrists formally consult with you about their litigation experiences, you are protected by the confidentiality inherent in the doctor-patient relationship.

Trust issues. Trust lies at the core of psychotherapeutic work. After being sued, you may find it difficult to re-establish trusting and comfortable relationships with patients, especially those who are seriously ill.

Well-trained, competent physicians who keep current with standards of care and have good relationships with patients do not expect to be sued. Psychiatrists often feel unrealistically immune to litigation because we believe our training helps us understand our own psychology and relationships with others. A charge of negligence exposes our vulnerabilities and leaves us feeling hurt and betrayed. As one psychiatrist ruefully observed, “I lost my innocence.”14

Countertransference feelings may emerge. Most physicians acknowledge that after being sued their relationships with patients change17,18—a particularly distressing outcome for psychiatrists. We may feel uncomfortable and threatened when we need to “stretch the patient-doctor relationship in a paternalistic direction,” such as when a psychotic patient needs involuntary commitment.15

Feelings that you must change the way you practice and chronic anxiety about your work are barriers to good practice. You may contemplate changing practice circumstances or retiring early. Personal therapy may help if you remain uneasy or cannot resolve life choices that overshadow your work with patients.

Medical or psychiatric care. Be alert to the point at which you or others involved in litigation need a referral for medical or psychiatric consultation. Sued physicians, their families, or colleagues often experience diagnosable psychiatric conditions or other behavioral problems, such as:

- major depression

- adjustment disorders

- posttraumatic stress disorder

- worsening of a previously diagnosed psychiatric illness

- physical symptoms that require diagnosis and treatment

- alcohol and drug misuse or abuse

- anxiety and distress that interfere with work

- self-medication, especially for insomnia

- disturbances and dysfunctional behaviors that affect marital and family life.19,20

SUPPORT YOUR COLLEAGUES

When consulting with other physicians, be aware of litigation factors that may influence treatment.

Become familiar with the climate of litigation in the jurisdiction where the case was filed, including the incidence and outcome of cases. For example, does an attempted suicide case usually result in settlement or—if it goes to trial—take 2 to 5 or more years to resolve? More than 70% of cases filed nationwide result in no payment (no settlement) for the plaintiff. If cases go to trial, physicians win 80% of the time.21

Recognize that the source of the physician’s distress may be the trauma associated with the initial bad outcome, rather than the malpractice suit itself. As the case progresses and facts emerge, you may play a large role in helping your physician patient correct previous distortions of the event. Certain periods—during trial, for example—might require more-frequent visits, medication, and expressions of support.

You may harbor a bias about the case, but withhold judgment until it is resolved.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. From exam room to court room: navigating litigation and coping with stress (CD-ROM) http://sales.acog.com/acb/stores/1/product1.cfm?SID=1&Product_ID=589).

- Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Physician Litigation Stress Resource Center. www.physicianlitigationstress.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Charles reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

‘Immediately after the event I was a wreck. I vaguely remember talking to the family; I don’t know if I was much use to them. … That night I got drunk. It was the only way I could sleep. A sensitive colleague came and sat with me.”1

Besides being targets of malpractice suits, psychiatrists also serve as resources for colleagues who are sued. Specific actions can help you and those you counsel deal with the stress of an adverse event before and during litigation. Remember that:

- anticipation is the best defense

- knowledge is power

- action counters passivity

- a supportive environment is essential.

ANTICIPATING LITIGATION

What is the risk? No nationwide reporting system tracks the incidence of medical malpractice claims, but industry experts suggest a claim is leveled against 7% of psychiatrists each year.2 The risk is higher for other medical specialists: a recent survey by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists found that 89% of practicing ObGyns had been sued at least once in their careers.3 Because a claim usually takes several years to resolve, a substantial number of physicians—including psychiatrists—are involved in litigation at any one time.

Successfully anticipating litigation begins with being familiar with your state’s statute of limitations—usually 2 to 3 years after discovery of the incident, with exceptions for children, the disabled, and designated special circumstances. If a plaintiff’s case is not filed within this time, a disputed outcome can never be the subject of a malpractice claim.

Adverse events. The severity of the outcome, the nature of your relationship with the patient, and the degree of your responsibility for an adverse event contribute to the intensity of your initial emotional response. If a mistake caused the event, your reaction may be even more severe.4-6 Whatever the event’s specifics, you may ruminate about your role and degree of responsibility (Table 1).

Table 1

Nagging questions after a ‘bad’ patient outcome

|

Expect that your view of the circumstances will generate a complex array of feelings: shock, anxiety, depression, shame, guilt, self-blame, disbelief, self-doubt and inadequacy, anger, and even relief from not having to work with a difficult patient anymore.

Patient suicide. More than one-half of psychiatrists and up to one-third of psychiatric residents experience a patient suicide.7-10 The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations reports that suicide is the most frequent sentinel event, representing 501 (13.1%) of the total 3,811 sentinel events reviewed since 1995.11 Professional Risk Management Services, a major medical malpractice insurer of psychiatrists, reports that suicide and attempted suicide are the most frequently identifiable causes of liability payments (Figure).

Figure 1 Psychiatric claims by cause of loss in the United States, 1998 to 2005

Almost all lawsuits assert multiple allegations of negligence, and “cause of loss” represents the main allegation made in the claim or lawsuit. Thus, the category of “incorrect treatment” may be alleged in a lawsuit based on a patient suicide, but the main or chief allegation/complaint is stated as “incorrect treatment.” The most frequent identifiable cause of loss is suicide and attempted suicide.

* “Other” includes administrative issues, abandonment, premises liability, Tarasoff, third parties (such as parents), retained object, libel/slander, boundary violation, deleted duplicate file, Fen-phen, lack of informed consent, forensic issues, and miscellaneous.

Source: Prepared by Professional Risk Management Services, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

Psychiatrists’ feelings of distress after a patient suicide mirror the personal sense of failure and inadequacy most physicians feel when they are unable to prevent a patient’s death or serious injury. At the same time, we must:

- deal with the event’s medical complications, with relevant notifications and disclosures (Table 2)

- address the emotional pain of the injured patient or family

- participate in mandated reviews

- recognize and manage our emotional disruption (Table 3).

Table 2

Recommended medical steps, notifications,

and disclosures after an adverse event

| MEDICAL STEPS Take necessary actions to limit further injury or disability Obtain appropriate consultations Review the medical record; anticipate the patient’s follow-up needs and make recommendations for further treatment |

| NOTIFICATIONS Follow the health care system’s and insurer’s guidelines for notifying the patient/family Inform the institution’s risk manager and your professional liability carrier as soon as possible Write a description of the event for the record and a narrative for your personal file (and your lawyer’s) in case a suit is filed later Do not talk with the media |

| DISCLOSURES Acknowledge your ethical obligation to be truthful Follow your institution’s and insurer’s disclosure guidelines Expect to feel intimidated and uneasy in discussing your role in the event Expect the patient/family to be angry and disappointed in you Convey an interest in the patient’s/family’s emotional state; express sorrow for their loss Tell the patient/family what you know for sure; don’t speculate about what is not known, and don’t make false promises or false reassurances Don’t hurry; give the patient/family time to ask questions Expect to feel better after a truthful exchange |

Table 3

Managing your emotions before and during litigation

| Anticipate having repeated thoughts and preoccupations about the event; work toward a realistic view of it |

| Recognize your feelings and work to understand their source |

| Talk with a trusted confidant (your spouse, colleague, etc.) about your feelings |

| Monitor your emotional and physical status and, if indicated, seek appropriate consultation |

| Avoid situations that generate anxiety and increase stress |

| Monitor and address changes in relationships with family, patients, colleagues, and staff |

| Be understanding of yourself and others; develop a realistic view of yourself as a ‘good doctor’ |

| Engage in active sports and take regular vacations unrelated to professional activities |

| Control what can be controlled |

Self-evaluation. To cope with distress when a patient dies, you could attend the funeral. If the death was by suicide, consider consulting with a therapist about your reactions or review the case with your supervisor. You also might:

- make changes in your practice that alert you to problem patients

- introduce a more structured approach to patients with particular clinical conditions, using practice guidelines as a resource12,13

- become more alert to patients who may benefit from consultation or referral.

Balance the time you devote to work and personal life. Schedule regular time for recreation and active sports, which can help you prepare for the prolonged stress that follows being sued. Engage a personal physician to monitor your physical and emotional health and to recommend appropriate referrals when indicated.

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER

What can I expect? A lawsuit generates a mixture of common emotions and exacerbates those felt at the time of the bad outcome: shock, outrage, anxiety, anguish, dread, depression, helplessness, hopelessness, feelings of being misunderstood, and the anger and vulnerability associated with a narcissistic injury. As one ObGyn stated, learning that a lawsuit was filed “just prolonged my misery.”14

Each of us reacts in our own way to a lawsuit—and differently to each lawsuit if we are sued more than once—because of:

- our personality traits and personal circumstances

- the specifics of each case

- our relationship with the patient

- the public nature of a lawsuit

- a range of other variables that makes each case unique.

Suddenly, we who perceive ourselves as caring, beneficent, well-meaning, and devoted to our patients are publicly accused of being careless and incompetent, of harming the patient by failing to meet our minimal obligations. Psychiatrists Richard Ferrell and Trevor Price15 capture the impact of these allegations:

"Here are the sense of assault and violation, the feelings of outrage and fear. Most painfully, here is the narcissistic injury, the astonishing wound to our understanding of ourselves as admirable, well-meaning people."

Litigation is a lengthy process with defined stages (Table 4). We have little control over a slow-paced process that involves an array of participants (lawyers, judges, jury, and experts) whose behavior is not predictable. This makes us feel dependent, vulnerable, and impotent.

Table 4

Stages of litigation: What happens in court

| Stage | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Summons | Notification that a suit has been filed |

| Complaint | The nature of the allegation in legal terms |

| Pleadings | The attorney begins to communicate with the court by filing motions, a request that the court do something |

| Discovery | A process designed to obtain information about the case:

|

| Summary judgment | A motion asking the court, after the facts have been established by discovery, to decide the validity of the case; if granted, the case is resolved without a trial by jury |

| Settlement | An agreement between parties that resolves their legal dispute |

| Trial | Case is presented to the judge or a judge and jury to determine culpability |

| Verdict | Decision reached by the deciding body |

| Post-trial | If the defendant receives an unfavorable verdict, motions may be offered to the court to void or appeal the verdict |

BE ACTIVE, NOT PASSIVE

What you can do. Contact your insurer and risk manager immediately. Inquire about the average length of litigation in your jurisdiction (might be 1 to 5 or more years, depending on locality, type of case, and severity of injury). Ask your lawyer to describe the steps in the process and your role as the case proceeds.

Take whatever steps are necessary to cover your clinical duties. If your initial emotional reaction is disruptive, obtain coverage or rearrange your schedule. Expect to change or limit your schedule before depositions and during trial to allow adequate time for preparation.

Accept the fact that you must play by rules far different from those of medical care. Litigation is time-consuming and frustrating. Delays and “continuances” are common in legal proceedings, so expect them. Consider adapting to your own situation strategies that other sued physicians have found useful in regaining control over their lives and work (Table 5).

Table 5

Regaining control: Managing your practice during litigation

| Learn as much as you can about the legal process |

| Introduce good risk management strategies, such as efficient record-keeping, into your practice |

| Clarify the responsibilities of office personnel and coverage responsibilities with associates |

| Rearrange office schedules during periods of increased stress |

| Re-evaluate your time commitments to work and family |

| Participate in relevant continuing education |

| Make sure your financial and estate planning is current |

| Cooperate with legal counsel |

| Devote sufficient time to deposition preparation and other demands of the case |

| Carefully evaluate the advice of legal and insurance counsel regarding a settlement |

| Do not try to “fit patients in” while on trial; trial is a full-time job |

GET NEEDED SUPPORT

Talking about the case. Sharing with responsible confidants your emotional reactions to being sued is healthy for you and others affected. Lawyers, however, may caution you not to “talk to anybody” about the case. They don’t want you to say anything that would suggest liability or jeopardize their defense of the case.

As psychiatrists, we know this is not good psychological advice. The support of others is a natural help during major life events that cause enormous stress and disruption.16 You can resolve this dilemma by accepting the discipline of talking about your feelings regarding the case without discussing the specifics of the case.

In addition to lawyers and claims representatives, you may talk with your spouse or another trusted person or colleague about your feelings. When other physicians or psychiatrists formally consult with you about their litigation experiences, you are protected by the confidentiality inherent in the doctor-patient relationship.

Trust issues. Trust lies at the core of psychotherapeutic work. After being sued, you may find it difficult to re-establish trusting and comfortable relationships with patients, especially those who are seriously ill.

Well-trained, competent physicians who keep current with standards of care and have good relationships with patients do not expect to be sued. Psychiatrists often feel unrealistically immune to litigation because we believe our training helps us understand our own psychology and relationships with others. A charge of negligence exposes our vulnerabilities and leaves us feeling hurt and betrayed. As one psychiatrist ruefully observed, “I lost my innocence.”14

Countertransference feelings may emerge. Most physicians acknowledge that after being sued their relationships with patients change17,18—a particularly distressing outcome for psychiatrists. We may feel uncomfortable and threatened when we need to “stretch the patient-doctor relationship in a paternalistic direction,” such as when a psychotic patient needs involuntary commitment.15

Feelings that you must change the way you practice and chronic anxiety about your work are barriers to good practice. You may contemplate changing practice circumstances or retiring early. Personal therapy may help if you remain uneasy or cannot resolve life choices that overshadow your work with patients.

Medical or psychiatric care. Be alert to the point at which you or others involved in litigation need a referral for medical or psychiatric consultation. Sued physicians, their families, or colleagues often experience diagnosable psychiatric conditions or other behavioral problems, such as:

- major depression

- adjustment disorders

- posttraumatic stress disorder

- worsening of a previously diagnosed psychiatric illness

- physical symptoms that require diagnosis and treatment

- alcohol and drug misuse or abuse

- anxiety and distress that interfere with work

- self-medication, especially for insomnia

- disturbances and dysfunctional behaviors that affect marital and family life.19,20

SUPPORT YOUR COLLEAGUES

When consulting with other physicians, be aware of litigation factors that may influence treatment.

Become familiar with the climate of litigation in the jurisdiction where the case was filed, including the incidence and outcome of cases. For example, does an attempted suicide case usually result in settlement or—if it goes to trial—take 2 to 5 or more years to resolve? More than 70% of cases filed nationwide result in no payment (no settlement) for the plaintiff. If cases go to trial, physicians win 80% of the time.21

Recognize that the source of the physician’s distress may be the trauma associated with the initial bad outcome, rather than the malpractice suit itself. As the case progresses and facts emerge, you may play a large role in helping your physician patient correct previous distortions of the event. Certain periods—during trial, for example—might require more-frequent visits, medication, and expressions of support.

You may harbor a bias about the case, but withhold judgment until it is resolved.

Related resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. From exam room to court room: navigating litigation and coping with stress (CD-ROM) http://sales.acog.com/acb/stores/1/product1.cfm?SID=1&Product_ID=589).

- Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Physician Litigation Stress Resource Center. www.physicianlitigationstress.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Charles reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Anonymous. Looking back… BMJ 2000;320(7237):812.-

2. Martin G, Tracy JD. President and CEO, Professional Risk Management Services. Personal communication. October 20, 2006.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG 2006 Professional Liability Survey. Washington, DC; 2006. Available at: http://www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=4&bulletin=3963. Accessed January 16, 2007.

4. Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med 1992;7(4):424-31.

5. Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320(7237):726-7.

6. Aasland OG, Forde R. Impact of feeling responsible for adverse events on doctors’ personal and professional lives: the importance of being open to criticism from colleagues. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2005;14:13-7.

7. Alexander DA, Klein S, Grey NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ 2000;320:1571-4.

8. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

9. Brown HN. The impact of suicide on therapists in training. Compr Psychiatry 1987;28:101-12.

10. Ellis TE, Dickey TO, Jones EC. Patient suicide in psychiatric residency programs: a national survey of training and postvention practices. Academic Psychiatry 1998;22:181-9.

11. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel event statistics. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/74540565-4D0F-4992-863E-8F9E949E6B56/0/se_stats_6_30_06.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2006.

12. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157(12):2022-7.

13. Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders (compendium 2006) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

14. Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:94,120.

15. Ferrell RB, Price TRP. Effects of malpractice suits on physicians. In: Gold JH, Nemiah JC, eds. Beyond transference. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993:141-58.

16. Watson PJ, Friedman MJ, Gibson LE, et al. Early intervention in trauma-related problems. In: Ursano R, Norwood AE, eds. Trauma and disaster: responses and management. Review of psychiatry vol. 22. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:100-1.

17. Charles SC, Psykoty CE, Nelson A. Physicians on trial—self-reported reactions to malpractice trials. West J Med 1988;148:358-60.

18. Charles SC. The doctor-patient relationship and medical malpractice litigation. Bull Menninger Clin 1993;57(2):195-207.

19. Charles SC, Wilbert JR, Franke KJ. Sued and non-sued physicians’ self-reported reactions to malpractice litigation. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:437-40.

20. Martin CA, Wilson JA, Fiebelman ND, et al. Physicians’ psychologic reactions to malpractice litigation. South Med J 1991;84:1300-4.

21. Outcome of closed medical malpractice claims. National data (1985-2005). Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA). Rockville, MD; 2006.

1. Anonymous. Looking back… BMJ 2000;320(7237):812.-

2. Martin G, Tracy JD. President and CEO, Professional Risk Management Services. Personal communication. October 20, 2006.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG 2006 Professional Liability Survey. Washington, DC; 2006. Available at: http://www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=4&bulletin=3963. Accessed January 16, 2007.

4. Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med 1992;7(4):424-31.

5. Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000;320(7237):726-7.

6. Aasland OG, Forde R. Impact of feeling responsible for adverse events on doctors’ personal and professional lives: the importance of being open to criticism from colleagues. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2005;14:13-7.

7. Alexander DA, Klein S, Grey NM, et al. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ 2000;320:1571-4.

8. Chemtob CM, Hamada RS, Bauer G, et al. Patients’ suicides: frequency and impact on psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:224-8.

9. Brown HN. The impact of suicide on therapists in training. Compr Psychiatry 1987;28:101-12.

10. Ellis TE, Dickey TO, Jones EC. Patient suicide in psychiatric residency programs: a national survey of training and postvention practices. Academic Psychiatry 1998;22:181-9.

11. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel event statistics. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/74540565-4D0F-4992-863E-8F9E949E6B56/0/se_stats_6_30_06.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2006.

12. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157(12):2022-7.

13. Practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders (compendium 2006) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

14. Charles SC, Frisch PR. Adverse events, stress and litigation: a physician’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:94,120.

15. Ferrell RB, Price TRP. Effects of malpractice suits on physicians. In: Gold JH, Nemiah JC, eds. Beyond transference. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993:141-58.

16. Watson PJ, Friedman MJ, Gibson LE, et al. Early intervention in trauma-related problems. In: Ursano R, Norwood AE, eds. Trauma and disaster: responses and management. Review of psychiatry vol. 22. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:100-1.

17. Charles SC, Psykoty CE, Nelson A. Physicians on trial—self-reported reactions to malpractice trials. West J Med 1988;148:358-60.

18. Charles SC. The doctor-patient relationship and medical malpractice litigation. Bull Menninger Clin 1993;57(2):195-207.

19. Charles SC, Wilbert JR, Franke KJ. Sued and non-sued physicians’ self-reported reactions to malpractice litigation. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:437-40.

20. Martin CA, Wilson JA, Fiebelman ND, et al. Physicians’ psychologic reactions to malpractice litigation. South Med J 1991;84:1300-4.

21. Outcome of closed medical malpractice claims. National data (1985-2005). Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA). Rockville, MD; 2006.