User login

Mr. N, age 48, has chronic mental illness and has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals for 30 years, with diagnoses of bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified, without psychotic features and schizophrenia. He often is delusional and disorganized and does not adhere to treatment. Since age 18, his psychiatric care has been sporadic; during his last admission 3 years ago, he refused treatment and left the hospital against medical advice. Mr. N is homeless and often eats out of a dumpster.

Recently, Mr. N was arrested for cocaine possession, for which he was held in custody. His mental status continued to deteriorate while in jail, where he was evaluated by a forensics examiner.

Mr. N was declared incompetent to stand trial and was transferred to a state psychiatric hospital.

In the hospital, the treatment team finds that Mr. N is disorganized and preoccupied with thoughts of not wanting to “lose control” to the physicians. He shows no evidence of suicidal or homicidal ideation or perceptual disturbance. Mr. N has difficulty grasping concepts, making plans, and following through with them. He has poor insight and impulse control and impaired judgment.

Mr. N’s past and present diagnoses include bipolar disorder without psychotic features, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, paranoid personality traits, borderline intelligence, cellulitis of both legs, and chronic venous stasis. Although he was arrested for cocaine possession, we are not able to obtain much information about his history of substance abuse because of his poor mental status.

What could be causing Mr. N’s deteriorating mental status?

a) substance withdrawal

b) malnutrition

c) worsening schizophrenia

d) untreated infection due to cellulitis

HISTORY Sporadic care

Mr. N can provide few details of his early life. He was adopted as a child. He spent time in juvenile detention center. He completed 10th grade but did not graduate from high school. Symptoms of mental illness emerged at age 18. His employment history is consistent with chronic mental illness: His longest job, at a grocery store, lasted only 6 months. He has had multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Over the years his treatment has included divalproex sodium, risperidone, paroxetine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, amitriptyline, methylphenidate, and a multivitamin; however, he often is noncompliant with treatment and was not taking any medications when he arrived at the hospital.

EVALUATION Possible deficiency

The treatment team discusses guardianship, but the public administrator’s office provides little support because of Mr. N’s refusal to stay in one place. He was evicted from his last apartment because of hoarding behavior, which created a fire hazard. He has been homeless most of his adult life, which might have significantly restricted his diet.

A routine laboratory workup—complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lipids—is ordered, revealing an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in the low range at 1,200/μL (normal range, 1,500 to 8,000/μL). Mr. N is offered treatment with a long-acting IM injection of risperidone because of his history of noncompliance, but he refuses the medication. Instead, he is started on oral risperidone, 2 mg/d.

The cellulitis of both lower limbs and chronic venous stasis are of concern; the medical team is consulted. Review of Mr. N’s medical records from an affiliated hospital reveals a history of vitamin B12 deficiency. Further tests show that the vitamin B12 level is low at <50 pg/mL (normal range, 160 to 950 pg/mL). Pernicious anemia had been ruled out after Mr. N tested negative for antibodies to intrinsic factor (a glycoprotein secreted in the stomach that is necessary for absorption of vitamin B12). Suspicion is that vitamin B12 deficiency is caused by Mr. N’s restricted diet in the context of chronic homelessness.

The authors’ observations

A review of the literature on vitamin B12 deficiency describes tingling or numbness, ataxia, and dementia; however, in rare cases, vitamin B12 deficiency presents with psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, mania, psychosis, dementia, and catatonia.1-13

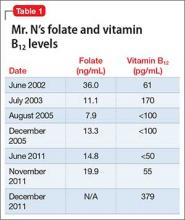

We suspected that Mr. N’s vitamin B12 deficiency could have been affecting his mental status; consequently, we ordered routine laboratory work-up that included a complete blood count with differential and peripheral smear, which showed macrocytic anemia and ovalocytes. We also tested his vitamin B12 level, which was very low at 55 pg/mL. These results, combined with his previously recorded vitamin B12 level (Table 1), suggested deficiency.

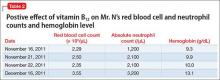

TREATMENT Oral medication

Two months after starting risperidone, the medical team recommends IM vitamin B12 as first-line treatment, but Mr. N refuses. We considered guardianship ex parte for involuntary administration of IM B12 injection to prevent life-threatening consequences of a non-healing ulcer on his leg that was related to his cellulitis. Meanwhile, we reviewed the literature on vitamin B12 therapy, including route, dosage, and outcome.14-23 Mr. N agrees to oral vitamin B12, 1,000 μg/d,21 and we no longer consider guardianship ex parte. Mr. N’s vitamin B12 level and clinical picture improve 1 month after oral vitamin B12 is added to oral risperidone. His thought process is more organized, he is no longer paranoid, and he shows improved insight and judgement. ANC and neutrophil count improve as well (Table 2). Mr. N’s ulcer begins to heal despite his noncompliance with wound care.

The forensic examiner sees Mr. N after 3 months of continued therapy. His thought pattern is more organized and he is able to comprehend the criminal charges against him and to work with his attorney. He is determined competent by the forensic examiner; in a court hearing, the judge finds Mr. N competent to stand trial.

The authors’ observations

Based on our experience treating Mr. N, we think that it is important to establish an association between vitamin B12 deficiency and psychosis. Vitamin B12 deficiency is uncommon; however, serum levels do not need to be significantly low to produce severe neuropsychiatric morbidity, which has been reported with serum levels ≤457 pg/mL.2-5,24,25 It is more frequent than the other organic causes of psychosis5,10,24 and Mr. N’s improvement further strengthened the correlation.

Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment for a deficiency, but oral or sublingual vitamin B12 can be given to patients who are disabled, geriatric, or refuse parenteral administration.21 Only approximately 1% of oral vitamin B12 is absorbed in patients who do not have intrinsic factor. The daily requirement of vitamin B12 is 1.0 to 2.5 μg/d; large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d therefore seem to be effective in correcting deficiency, even in the presence of intrinsic factor deficiency.15,20,21 Large oral dosages also benefit other hematological abnormalities, such as a low white blood cell count and neutropenia.

How vitamin B12 deficiency affects neuropsychiatric illness

Vitamin B12 is essential for methylation, a process crucial for the formation of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. A low level of vitamin B12 can interrupt methylation and cause accumulation of homocysteine and impaired metabolism of serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. Hyperhomocysteinemia can contribute to cerebral dysfunction by causing vascular injury.26

Vitamin B12 also is involved in tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis in the brain, which is pivotal for synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters. Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to accumulation of methyltetrahydrofolate, an excitatory neurotoxin. All of these can contribute to development of psychosis. Therefore, a defect in the methylation process could be responsible for the neuropsychiatric manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency.

What did we learn from Mr. N?

In most people, vitamin B12 levels are normal, however, we recommend that clinicians consider vitamin B12 deficiency when a patient has new-onset or unresponsive psychosis,27 particularly in a homeless person or one who has a restricted diet.28 It is important to rule out vitamin B12 deficiency in a patient with a low serum folate level because folic acid therapy could exacerbate neurologic manifestations of underlying vitamin B12 deficiency and increase the risk of permanent nerve damage and cognitive decline.

We were intrigued to see improvement in Mr. N after we added vitamin B12 to his ongoing treatment with an antipsychotic. We did not believe that vitamin B12 supplementation was the sole reason his mental status improved enough to be found competent to stand trial, although we believe that initiating oral vitamin B12 was beneficial for Mr. N.

Last, this case supports the need for research to further explore the role of vitamin B12 in refractory psychosis, depression, and mania.

Bottom Line

Vitamin B12 deficiency can contribute to psychosis and other psychiatric disorders, especially in patients with a restricted diet, such as those who are homeless. Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment, but oral supplementation can be used if the patient refuses therapy. Large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d seem to be effective in correcting vitamin B12 deficiency.

Related Resources

• Ramsey D, Muskin PR. Vitamin deficiencies and mental health: How are they linked? Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):37-43.

• Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risperidone • Risperdal

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jan Jill-Jordan, PhD, for her help preparing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dogan M, Ozdemir O, Sal EA, et al. Psychotic disorder and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(3):205-207.

2. Levine J, Stahl Z, Sela BA, et al. Elevated homocysteine levels in young male patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1790-1792.

3. Jauhar S, Blackett A, Srireddy P, et al. Pernicious anaemia presenting as catatonia without signs of anaemia or macrocytosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):244-245.

4. de Carvalho Abi-Abib R, Milech A, Ramalho FV, et al. Psychosis as the initial manifestation of pernicious anemia in a type 1 diabetes mellitus patient. Endocrinologist. 2010;20(5):224-225.

5. Berry N, Sagar R, Tripathi BM. Catatonia and other psychiatric symptoms with vitamin B12 deficiency. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(2):156-159.

6. Zucker DK, Livingston RL, Nakra R, et al. B12 deficiency and psychiatric disorders: case report and literature review. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(2):197-205.

7. Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(9):1393-1412.

8. Roze E, Gervais D, Demeret S, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances in presumed late-onset cobalamin C disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1457-1462.

9. Lewis AL, Pelic C, Kahn DA. Malignant catatonia in a patient with bipolar disorder, B12 deficiency, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: one cause or three? J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(5):415-422.

10. Rajkumar AP, Jebaraj P. Chronic psychosis associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:115-116.

11. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

12. Smith R, Oliver RA. Sudden onset of psychosis in association with vitamin-B12 deficiency. Br Med J. 1967;3(5556):34.

13. Russell RM, Baik HW. Clinical implications of vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Nutrition in Clinical Care. 2001;4(4):214-220.

14. Sharabi A, Cohen E, Sulkes J, et al. Replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency: comparison between the sublingual and oral route. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003; 56(6):635-638.

15. Chalmers RA, Bain MD, Costello I. Oral cobalamin therapy. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):148.

16. Borchardt J, Malnick S. Sublingual cobalamin for pernicious anaemia. Lancet. 1999;354(9195):2081.

17. Seal EC, Metz J, Flicker L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral vitamin B12 supplementation in older patients with subnormal or borderline serum vitamin B12 concentrations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):146-151.

18. Erkurt MA, Aydogdu I, Dikilitas M, et al. Effects of cyanocobalamin on immunity in patients with pernicious anemia. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(2):131-135.

19. Andrès E, Kaltenbach G, Noel E, et al. Efficacy of short-term oral cobalamin therapy for the treatment of cobalamin deficiencies related to food-cobalamin malabsorption: a study of 30 patients. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25(3):161-166.

20. Wellmer J, Sturm KU, Herrmann W, et al. Oral treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency in subacute combined degeneration [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2006;77(10):1228-1231.

21. Lederle FA. Oral cobalamin for pernicious anemia. Medicine‘s best kept secret? JAMA. 1991;265(1):94-95.

22. Chalouhi C, Faesch S, Anthoine-Milhomme MC, et al. Neurological consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency and its treatment. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(8):538-541.

23. Andrès E, Federici L, Affenberger S, et al. B12 deficiency: a look beyond pernicious anemia. J Fam Pract. 2007;56(7):537-542.

24. Aaron S, Kumar S, Vijayan J, et al. Clinical and laboratory features and response to treatment in patients presenting with vitamin B12 deficiency related neurological syndromes. Neurol India. 2005;53(1):55-58.

25. Saperstein DS, Wolfe GI, Gronseth GS, et al. Challenges in the identification of cobalamin-deficiency polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1296-1301.

26. Tsai AC, Morel CF, Scharer G, et al. Late-onset combined homocystinuria and methylmalonic aciduria (cblC) and neuropsychiatric disturbance. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(20):2430-2434.

27. Brett AS, Roberts MS. Screening for vitamin B12 deficiency in psychiatric patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(9):522-524.

28. Kaltenbach G, Noblet-Dick M, Barnier-Figue G, et al. Early normalization of low vitamin B12 levels by oral cobalamin therapy in three older patients with pernicious anemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1914-1915.

Mr. N, age 48, has chronic mental illness and has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals for 30 years, with diagnoses of bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified, without psychotic features and schizophrenia. He often is delusional and disorganized and does not adhere to treatment. Since age 18, his psychiatric care has been sporadic; during his last admission 3 years ago, he refused treatment and left the hospital against medical advice. Mr. N is homeless and often eats out of a dumpster.

Recently, Mr. N was arrested for cocaine possession, for which he was held in custody. His mental status continued to deteriorate while in jail, where he was evaluated by a forensics examiner.

Mr. N was declared incompetent to stand trial and was transferred to a state psychiatric hospital.

In the hospital, the treatment team finds that Mr. N is disorganized and preoccupied with thoughts of not wanting to “lose control” to the physicians. He shows no evidence of suicidal or homicidal ideation or perceptual disturbance. Mr. N has difficulty grasping concepts, making plans, and following through with them. He has poor insight and impulse control and impaired judgment.

Mr. N’s past and present diagnoses include bipolar disorder without psychotic features, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, paranoid personality traits, borderline intelligence, cellulitis of both legs, and chronic venous stasis. Although he was arrested for cocaine possession, we are not able to obtain much information about his history of substance abuse because of his poor mental status.

What could be causing Mr. N’s deteriorating mental status?

a) substance withdrawal

b) malnutrition

c) worsening schizophrenia

d) untreated infection due to cellulitis

HISTORY Sporadic care

Mr. N can provide few details of his early life. He was adopted as a child. He spent time in juvenile detention center. He completed 10th grade but did not graduate from high school. Symptoms of mental illness emerged at age 18. His employment history is consistent with chronic mental illness: His longest job, at a grocery store, lasted only 6 months. He has had multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Over the years his treatment has included divalproex sodium, risperidone, paroxetine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, amitriptyline, methylphenidate, and a multivitamin; however, he often is noncompliant with treatment and was not taking any medications when he arrived at the hospital.

EVALUATION Possible deficiency

The treatment team discusses guardianship, but the public administrator’s office provides little support because of Mr. N’s refusal to stay in one place. He was evicted from his last apartment because of hoarding behavior, which created a fire hazard. He has been homeless most of his adult life, which might have significantly restricted his diet.

A routine laboratory workup—complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lipids—is ordered, revealing an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in the low range at 1,200/μL (normal range, 1,500 to 8,000/μL). Mr. N is offered treatment with a long-acting IM injection of risperidone because of his history of noncompliance, but he refuses the medication. Instead, he is started on oral risperidone, 2 mg/d.

The cellulitis of both lower limbs and chronic venous stasis are of concern; the medical team is consulted. Review of Mr. N’s medical records from an affiliated hospital reveals a history of vitamin B12 deficiency. Further tests show that the vitamin B12 level is low at <50 pg/mL (normal range, 160 to 950 pg/mL). Pernicious anemia had been ruled out after Mr. N tested negative for antibodies to intrinsic factor (a glycoprotein secreted in the stomach that is necessary for absorption of vitamin B12). Suspicion is that vitamin B12 deficiency is caused by Mr. N’s restricted diet in the context of chronic homelessness.

The authors’ observations

A review of the literature on vitamin B12 deficiency describes tingling or numbness, ataxia, and dementia; however, in rare cases, vitamin B12 deficiency presents with psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, mania, psychosis, dementia, and catatonia.1-13

We suspected that Mr. N’s vitamin B12 deficiency could have been affecting his mental status; consequently, we ordered routine laboratory work-up that included a complete blood count with differential and peripheral smear, which showed macrocytic anemia and ovalocytes. We also tested his vitamin B12 level, which was very low at 55 pg/mL. These results, combined with his previously recorded vitamin B12 level (Table 1), suggested deficiency.

TREATMENT Oral medication

Two months after starting risperidone, the medical team recommends IM vitamin B12 as first-line treatment, but Mr. N refuses. We considered guardianship ex parte for involuntary administration of IM B12 injection to prevent life-threatening consequences of a non-healing ulcer on his leg that was related to his cellulitis. Meanwhile, we reviewed the literature on vitamin B12 therapy, including route, dosage, and outcome.14-23 Mr. N agrees to oral vitamin B12, 1,000 μg/d,21 and we no longer consider guardianship ex parte. Mr. N’s vitamin B12 level and clinical picture improve 1 month after oral vitamin B12 is added to oral risperidone. His thought process is more organized, he is no longer paranoid, and he shows improved insight and judgement. ANC and neutrophil count improve as well (Table 2). Mr. N’s ulcer begins to heal despite his noncompliance with wound care.

The forensic examiner sees Mr. N after 3 months of continued therapy. His thought pattern is more organized and he is able to comprehend the criminal charges against him and to work with his attorney. He is determined competent by the forensic examiner; in a court hearing, the judge finds Mr. N competent to stand trial.

The authors’ observations

Based on our experience treating Mr. N, we think that it is important to establish an association between vitamin B12 deficiency and psychosis. Vitamin B12 deficiency is uncommon; however, serum levels do not need to be significantly low to produce severe neuropsychiatric morbidity, which has been reported with serum levels ≤457 pg/mL.2-5,24,25 It is more frequent than the other organic causes of psychosis5,10,24 and Mr. N’s improvement further strengthened the correlation.

Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment for a deficiency, but oral or sublingual vitamin B12 can be given to patients who are disabled, geriatric, or refuse parenteral administration.21 Only approximately 1% of oral vitamin B12 is absorbed in patients who do not have intrinsic factor. The daily requirement of vitamin B12 is 1.0 to 2.5 μg/d; large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d therefore seem to be effective in correcting deficiency, even in the presence of intrinsic factor deficiency.15,20,21 Large oral dosages also benefit other hematological abnormalities, such as a low white blood cell count and neutropenia.

How vitamin B12 deficiency affects neuropsychiatric illness

Vitamin B12 is essential for methylation, a process crucial for the formation of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. A low level of vitamin B12 can interrupt methylation and cause accumulation of homocysteine and impaired metabolism of serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. Hyperhomocysteinemia can contribute to cerebral dysfunction by causing vascular injury.26

Vitamin B12 also is involved in tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis in the brain, which is pivotal for synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters. Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to accumulation of methyltetrahydrofolate, an excitatory neurotoxin. All of these can contribute to development of psychosis. Therefore, a defect in the methylation process could be responsible for the neuropsychiatric manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency.

What did we learn from Mr. N?

In most people, vitamin B12 levels are normal, however, we recommend that clinicians consider vitamin B12 deficiency when a patient has new-onset or unresponsive psychosis,27 particularly in a homeless person or one who has a restricted diet.28 It is important to rule out vitamin B12 deficiency in a patient with a low serum folate level because folic acid therapy could exacerbate neurologic manifestations of underlying vitamin B12 deficiency and increase the risk of permanent nerve damage and cognitive decline.

We were intrigued to see improvement in Mr. N after we added vitamin B12 to his ongoing treatment with an antipsychotic. We did not believe that vitamin B12 supplementation was the sole reason his mental status improved enough to be found competent to stand trial, although we believe that initiating oral vitamin B12 was beneficial for Mr. N.

Last, this case supports the need for research to further explore the role of vitamin B12 in refractory psychosis, depression, and mania.

Bottom Line

Vitamin B12 deficiency can contribute to psychosis and other psychiatric disorders, especially in patients with a restricted diet, such as those who are homeless. Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment, but oral supplementation can be used if the patient refuses therapy. Large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d seem to be effective in correcting vitamin B12 deficiency.

Related Resources

• Ramsey D, Muskin PR. Vitamin deficiencies and mental health: How are they linked? Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):37-43.

• Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risperidone • Risperdal

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jan Jill-Jordan, PhD, for her help preparing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mr. N, age 48, has chronic mental illness and has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals for 30 years, with diagnoses of bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified, without psychotic features and schizophrenia. He often is delusional and disorganized and does not adhere to treatment. Since age 18, his psychiatric care has been sporadic; during his last admission 3 years ago, he refused treatment and left the hospital against medical advice. Mr. N is homeless and often eats out of a dumpster.

Recently, Mr. N was arrested for cocaine possession, for which he was held in custody. His mental status continued to deteriorate while in jail, where he was evaluated by a forensics examiner.

Mr. N was declared incompetent to stand trial and was transferred to a state psychiatric hospital.

In the hospital, the treatment team finds that Mr. N is disorganized and preoccupied with thoughts of not wanting to “lose control” to the physicians. He shows no evidence of suicidal or homicidal ideation or perceptual disturbance. Mr. N has difficulty grasping concepts, making plans, and following through with them. He has poor insight and impulse control and impaired judgment.

Mr. N’s past and present diagnoses include bipolar disorder without psychotic features, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, paranoid personality traits, borderline intelligence, cellulitis of both legs, and chronic venous stasis. Although he was arrested for cocaine possession, we are not able to obtain much information about his history of substance abuse because of his poor mental status.

What could be causing Mr. N’s deteriorating mental status?

a) substance withdrawal

b) malnutrition

c) worsening schizophrenia

d) untreated infection due to cellulitis

HISTORY Sporadic care

Mr. N can provide few details of his early life. He was adopted as a child. He spent time in juvenile detention center. He completed 10th grade but did not graduate from high school. Symptoms of mental illness emerged at age 18. His employment history is consistent with chronic mental illness: His longest job, at a grocery store, lasted only 6 months. He has had multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Over the years his treatment has included divalproex sodium, risperidone, paroxetine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, amitriptyline, methylphenidate, and a multivitamin; however, he often is noncompliant with treatment and was not taking any medications when he arrived at the hospital.

EVALUATION Possible deficiency

The treatment team discusses guardianship, but the public administrator’s office provides little support because of Mr. N’s refusal to stay in one place. He was evicted from his last apartment because of hoarding behavior, which created a fire hazard. He has been homeless most of his adult life, which might have significantly restricted his diet.

A routine laboratory workup—complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lipids—is ordered, revealing an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in the low range at 1,200/μL (normal range, 1,500 to 8,000/μL). Mr. N is offered treatment with a long-acting IM injection of risperidone because of his history of noncompliance, but he refuses the medication. Instead, he is started on oral risperidone, 2 mg/d.

The cellulitis of both lower limbs and chronic venous stasis are of concern; the medical team is consulted. Review of Mr. N’s medical records from an affiliated hospital reveals a history of vitamin B12 deficiency. Further tests show that the vitamin B12 level is low at <50 pg/mL (normal range, 160 to 950 pg/mL). Pernicious anemia had been ruled out after Mr. N tested negative for antibodies to intrinsic factor (a glycoprotein secreted in the stomach that is necessary for absorption of vitamin B12). Suspicion is that vitamin B12 deficiency is caused by Mr. N’s restricted diet in the context of chronic homelessness.

The authors’ observations

A review of the literature on vitamin B12 deficiency describes tingling or numbness, ataxia, and dementia; however, in rare cases, vitamin B12 deficiency presents with psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, mania, psychosis, dementia, and catatonia.1-13

We suspected that Mr. N’s vitamin B12 deficiency could have been affecting his mental status; consequently, we ordered routine laboratory work-up that included a complete blood count with differential and peripheral smear, which showed macrocytic anemia and ovalocytes. We also tested his vitamin B12 level, which was very low at 55 pg/mL. These results, combined with his previously recorded vitamin B12 level (Table 1), suggested deficiency.

TREATMENT Oral medication

Two months after starting risperidone, the medical team recommends IM vitamin B12 as first-line treatment, but Mr. N refuses. We considered guardianship ex parte for involuntary administration of IM B12 injection to prevent life-threatening consequences of a non-healing ulcer on his leg that was related to his cellulitis. Meanwhile, we reviewed the literature on vitamin B12 therapy, including route, dosage, and outcome.14-23 Mr. N agrees to oral vitamin B12, 1,000 μg/d,21 and we no longer consider guardianship ex parte. Mr. N’s vitamin B12 level and clinical picture improve 1 month after oral vitamin B12 is added to oral risperidone. His thought process is more organized, he is no longer paranoid, and he shows improved insight and judgement. ANC and neutrophil count improve as well (Table 2). Mr. N’s ulcer begins to heal despite his noncompliance with wound care.

The forensic examiner sees Mr. N after 3 months of continued therapy. His thought pattern is more organized and he is able to comprehend the criminal charges against him and to work with his attorney. He is determined competent by the forensic examiner; in a court hearing, the judge finds Mr. N competent to stand trial.

The authors’ observations

Based on our experience treating Mr. N, we think that it is important to establish an association between vitamin B12 deficiency and psychosis. Vitamin B12 deficiency is uncommon; however, serum levels do not need to be significantly low to produce severe neuropsychiatric morbidity, which has been reported with serum levels ≤457 pg/mL.2-5,24,25 It is more frequent than the other organic causes of psychosis5,10,24 and Mr. N’s improvement further strengthened the correlation.

Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment for a deficiency, but oral or sublingual vitamin B12 can be given to patients who are disabled, geriatric, or refuse parenteral administration.21 Only approximately 1% of oral vitamin B12 is absorbed in patients who do not have intrinsic factor. The daily requirement of vitamin B12 is 1.0 to 2.5 μg/d; large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d therefore seem to be effective in correcting deficiency, even in the presence of intrinsic factor deficiency.15,20,21 Large oral dosages also benefit other hematological abnormalities, such as a low white blood cell count and neutropenia.

How vitamin B12 deficiency affects neuropsychiatric illness

Vitamin B12 is essential for methylation, a process crucial for the formation of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. A low level of vitamin B12 can interrupt methylation and cause accumulation of homocysteine and impaired metabolism of serotonin, dopamine, and epinephrine. Hyperhomocysteinemia can contribute to cerebral dysfunction by causing vascular injury.26

Vitamin B12 also is involved in tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis in the brain, which is pivotal for synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters. Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to accumulation of methyltetrahydrofolate, an excitatory neurotoxin. All of these can contribute to development of psychosis. Therefore, a defect in the methylation process could be responsible for the neuropsychiatric manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency.

What did we learn from Mr. N?

In most people, vitamin B12 levels are normal, however, we recommend that clinicians consider vitamin B12 deficiency when a patient has new-onset or unresponsive psychosis,27 particularly in a homeless person or one who has a restricted diet.28 It is important to rule out vitamin B12 deficiency in a patient with a low serum folate level because folic acid therapy could exacerbate neurologic manifestations of underlying vitamin B12 deficiency and increase the risk of permanent nerve damage and cognitive decline.

We were intrigued to see improvement in Mr. N after we added vitamin B12 to his ongoing treatment with an antipsychotic. We did not believe that vitamin B12 supplementation was the sole reason his mental status improved enough to be found competent to stand trial, although we believe that initiating oral vitamin B12 was beneficial for Mr. N.

Last, this case supports the need for research to further explore the role of vitamin B12 in refractory psychosis, depression, and mania.

Bottom Line

Vitamin B12 deficiency can contribute to psychosis and other psychiatric disorders, especially in patients with a restricted diet, such as those who are homeless. Parenteral vitamin B12 therapy is the first-line treatment, but oral supplementation can be used if the patient refuses therapy. Large oral dosages of 1,000 to 5,000 μg/d seem to be effective in correcting vitamin B12 deficiency.

Related Resources

• Ramsey D, Muskin PR. Vitamin deficiencies and mental health: How are they linked? Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):37-43.

• Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26):1720-1728.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risperidone • Risperdal

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jan Jill-Jordan, PhD, for her help preparing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Dogan M, Ozdemir O, Sal EA, et al. Psychotic disorder and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(3):205-207.

2. Levine J, Stahl Z, Sela BA, et al. Elevated homocysteine levels in young male patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1790-1792.

3. Jauhar S, Blackett A, Srireddy P, et al. Pernicious anaemia presenting as catatonia without signs of anaemia or macrocytosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):244-245.

4. de Carvalho Abi-Abib R, Milech A, Ramalho FV, et al. Psychosis as the initial manifestation of pernicious anemia in a type 1 diabetes mellitus patient. Endocrinologist. 2010;20(5):224-225.

5. Berry N, Sagar R, Tripathi BM. Catatonia and other psychiatric symptoms with vitamin B12 deficiency. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(2):156-159.

6. Zucker DK, Livingston RL, Nakra R, et al. B12 deficiency and psychiatric disorders: case report and literature review. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(2):197-205.

7. Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(9):1393-1412.

8. Roze E, Gervais D, Demeret S, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances in presumed late-onset cobalamin C disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1457-1462.

9. Lewis AL, Pelic C, Kahn DA. Malignant catatonia in a patient with bipolar disorder, B12 deficiency, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: one cause or three? J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(5):415-422.

10. Rajkumar AP, Jebaraj P. Chronic psychosis associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:115-116.

11. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

12. Smith R, Oliver RA. Sudden onset of psychosis in association with vitamin-B12 deficiency. Br Med J. 1967;3(5556):34.

13. Russell RM, Baik HW. Clinical implications of vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Nutrition in Clinical Care. 2001;4(4):214-220.

14. Sharabi A, Cohen E, Sulkes J, et al. Replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency: comparison between the sublingual and oral route. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003; 56(6):635-638.

15. Chalmers RA, Bain MD, Costello I. Oral cobalamin therapy. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):148.

16. Borchardt J, Malnick S. Sublingual cobalamin for pernicious anaemia. Lancet. 1999;354(9195):2081.

17. Seal EC, Metz J, Flicker L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral vitamin B12 supplementation in older patients with subnormal or borderline serum vitamin B12 concentrations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):146-151.

18. Erkurt MA, Aydogdu I, Dikilitas M, et al. Effects of cyanocobalamin on immunity in patients with pernicious anemia. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(2):131-135.

19. Andrès E, Kaltenbach G, Noel E, et al. Efficacy of short-term oral cobalamin therapy for the treatment of cobalamin deficiencies related to food-cobalamin malabsorption: a study of 30 patients. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25(3):161-166.

20. Wellmer J, Sturm KU, Herrmann W, et al. Oral treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency in subacute combined degeneration [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2006;77(10):1228-1231.

21. Lederle FA. Oral cobalamin for pernicious anemia. Medicine‘s best kept secret? JAMA. 1991;265(1):94-95.

22. Chalouhi C, Faesch S, Anthoine-Milhomme MC, et al. Neurological consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency and its treatment. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(8):538-541.

23. Andrès E, Federici L, Affenberger S, et al. B12 deficiency: a look beyond pernicious anemia. J Fam Pract. 2007;56(7):537-542.

24. Aaron S, Kumar S, Vijayan J, et al. Clinical and laboratory features and response to treatment in patients presenting with vitamin B12 deficiency related neurological syndromes. Neurol India. 2005;53(1):55-58.

25. Saperstein DS, Wolfe GI, Gronseth GS, et al. Challenges in the identification of cobalamin-deficiency polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1296-1301.

26. Tsai AC, Morel CF, Scharer G, et al. Late-onset combined homocystinuria and methylmalonic aciduria (cblC) and neuropsychiatric disturbance. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(20):2430-2434.

27. Brett AS, Roberts MS. Screening for vitamin B12 deficiency in psychiatric patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(9):522-524.

28. Kaltenbach G, Noblet-Dick M, Barnier-Figue G, et al. Early normalization of low vitamin B12 levels by oral cobalamin therapy in three older patients with pernicious anemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1914-1915.

1. Dogan M, Ozdemir O, Sal EA, et al. Psychotic disorder and extrapyramidal symptoms associated with vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(3):205-207.

2. Levine J, Stahl Z, Sela BA, et al. Elevated homocysteine levels in young male patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1790-1792.

3. Jauhar S, Blackett A, Srireddy P, et al. Pernicious anaemia presenting as catatonia without signs of anaemia or macrocytosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):244-245.

4. de Carvalho Abi-Abib R, Milech A, Ramalho FV, et al. Psychosis as the initial manifestation of pernicious anemia in a type 1 diabetes mellitus patient. Endocrinologist. 2010;20(5):224-225.

5. Berry N, Sagar R, Tripathi BM. Catatonia and other psychiatric symptoms with vitamin B12 deficiency. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(2):156-159.

6. Zucker DK, Livingston RL, Nakra R, et al. B12 deficiency and psychiatric disorders: case report and literature review. Biol Psychiatry. 1981;16(2):197-205.

7. Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(9):1393-1412.

8. Roze E, Gervais D, Demeret S, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances in presumed late-onset cobalamin C disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1457-1462.

9. Lewis AL, Pelic C, Kahn DA. Malignant catatonia in a patient with bipolar disorder, B12 deficiency, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: one cause or three? J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(5):415-422.

10. Rajkumar AP, Jebaraj P. Chronic psychosis associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:115-116.

11. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

12. Smith R, Oliver RA. Sudden onset of psychosis in association with vitamin-B12 deficiency. Br Med J. 1967;3(5556):34.

13. Russell RM, Baik HW. Clinical implications of vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Nutrition in Clinical Care. 2001;4(4):214-220.

14. Sharabi A, Cohen E, Sulkes J, et al. Replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency: comparison between the sublingual and oral route. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003; 56(6):635-638.

15. Chalmers RA, Bain MD, Costello I. Oral cobalamin therapy. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):148.

16. Borchardt J, Malnick S. Sublingual cobalamin for pernicious anaemia. Lancet. 1999;354(9195):2081.

17. Seal EC, Metz J, Flicker L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral vitamin B12 supplementation in older patients with subnormal or borderline serum vitamin B12 concentrations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):146-151.

18. Erkurt MA, Aydogdu I, Dikilitas M, et al. Effects of cyanocobalamin on immunity in patients with pernicious anemia. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(2):131-135.

19. Andrès E, Kaltenbach G, Noel E, et al. Efficacy of short-term oral cobalamin therapy for the treatment of cobalamin deficiencies related to food-cobalamin malabsorption: a study of 30 patients. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25(3):161-166.

20. Wellmer J, Sturm KU, Herrmann W, et al. Oral treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency in subacute combined degeneration [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2006;77(10):1228-1231.

21. Lederle FA. Oral cobalamin for pernicious anemia. Medicine‘s best kept secret? JAMA. 1991;265(1):94-95.

22. Chalouhi C, Faesch S, Anthoine-Milhomme MC, et al. Neurological consequences of vitamin B12 deficiency and its treatment. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(8):538-541.

23. Andrès E, Federici L, Affenberger S, et al. B12 deficiency: a look beyond pernicious anemia. J Fam Pract. 2007;56(7):537-542.

24. Aaron S, Kumar S, Vijayan J, et al. Clinical and laboratory features and response to treatment in patients presenting with vitamin B12 deficiency related neurological syndromes. Neurol India. 2005;53(1):55-58.

25. Saperstein DS, Wolfe GI, Gronseth GS, et al. Challenges in the identification of cobalamin-deficiency polyneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(9):1296-1301.

26. Tsai AC, Morel CF, Scharer G, et al. Late-onset combined homocystinuria and methylmalonic aciduria (cblC) and neuropsychiatric disturbance. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(20):2430-2434.

27. Brett AS, Roberts MS. Screening for vitamin B12 deficiency in psychiatric patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(9):522-524.

28. Kaltenbach G, Noblet-Dick M, Barnier-Figue G, et al. Early normalization of low vitamin B12 levels by oral cobalamin therapy in three older patients with pernicious anemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(11):1914-1915.