User login

Like all physicians, psychiatrists practice in an increasingly complex health care environment, with escalating demands for productivity, rising threats of malpractice, expanding clinical oversight, and growing concerns about income. Additionally, psychiatric practice presents its own challenges, including limited resources and concerns about patient violence and suicide. These concerns can make it difficult to establish a healthy work–life balance.

Physicians, including psychiatrists, are at risk for alcohol or substance abuse/dependency, burnout, and suicide. As psychiatrists, we need to attend to our own personal and professional health so that we can best help our patients. This review focuses on the challenges psychiatrists face that can adversely affect their well-being and offers strategies to reduce the risk of burnout and enhance wellness.

The challenges of medicine and their impact on psychiatrists

The practice of medicine is inherently challenging. It requires hard work, discipline, dedication, and faithfulness to high ethical standards. Additional challenges include declining autonomy and opportunities for social support, increasing accountability, and a growing interest in reducing the cost of care by employing more non-physician health professionals—which in psychiatry typically include psychologists, nurse practitioners, and social workers. The uncertainty of the Affordable Care Act, declining income, and concerns about the nature of future medical practice are also stressors.1,2

Factors that contribute to psychiatrists’ stress include:

- limited resources

- concerns about patient violence and suicide

- crowded inpatient units

- changing culture in mental health services

- high work demands

- poorly defined roles of consultants

- declining authority

- frustration with the inability to impact systemic change

- conflict between responsibility toward employers vs the patient

- isolation.3

Concern about patient suicide is a significant stressor.4,5 Some evidence suggests that the impact of a patient’s suicide on a physician is more severe when it occurs during training than after graduation and is inversely correlated with the clinician’s perceived social integration into their professional network.5

Impediments to a physician’s well-being

Alcohol abuse/dependence. Approximately 13% of male physicians and 21% of female physicians meet Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Version C criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, according to a study of approximately 7,300 U.S. physicians from all specialties.6 (In this study, prescription drug abuse and use of illicit drugs were rare.) Age, hours worked, male sex, being married or partnered, having children, and being in a specialty other than internal medicine were independently associated with alcohol abuse or dependence.

Fortunately, psychiatrists were among the specialties with below average likelihood to meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse/dependency.6 However, alcohol abuse or dependency was associated with burnout, depression, suicidal ideation, lower quality of life, lower career satisfaction, and medical errors.

Burnout is a long-term stress reaction consisting of:

- physical and emotional exhaustion (feeling depleted)

- depersonalization (cynicism, lack of engagement with or negative attitudes toward patients)

- reduced sense of personal accomplishment (lack of a sense of purpose).7

In a 2017 survey of >14,000 U.S. physicians from 27 specialties, 42% of psychiatrists reported burnout.8 In another survey of approximately 300 resident physicians across all specialties in a tertiary academic hospital, 69% met criteria for burnout.9 This condition affects resident physicians as well as those in practice. Residents and program directors cited a lack of work–life balance and feeling unappreciated as factors contributing to burnout.

Among physicians, factors that contribute to burnout include loss of autonomy, diminished status as physicians, and increased work pressures. Burnout has a negative impact on both patients and health care systems. It is associated with an increased risk of depression and can contribute to:

- broken relationships

- alcohol abuse

- physician suicide

- decreased quality of care, including patient safety and satisfaction

- increased risk of malpractice suits

- reduced patient adherence to medical recommendations.5,10-12

Physicians who embrace medicine as a calling (ie, committing one’s life to personally meaningful work that serves a prosocial purpose) experience less burnout. According to a survey of approximately 900 primary care physicians and 300 psychiatrists, 42% of psychiatrists strongly agreed that medicine is a calling.13 Overall, physicians with a high sense of calling reported less burnout than those with a lower sense of calling (17% vs 31%, respectively).13

Depression and suicide. Gold et al12 analyzed a database that included information on approximately 31,600 adult suicide victims, and 203 of these victims were physicians. Compared with others, physicians were more likely to have a diagnosed mental illness or an occupation-related problem that contributed to suicide. Toxicology results also showed that physician suicide victims were significantly more likely than non-physician victims to test positive for benzodiazepines and barbiturates, but not antidepressants, which suggests that physicians with depression may not have been receiving adequate treatment.12

Although occupation-related stress and inadequate mental health treatment may be modifiable risk factors to reduce suicide deaths among physicians, stigma and fear of medical staff and licensure issues may deter physicians from seeking treatment.14

Steps to avoid burnout

Evidence-based interventions. There is limited evidence-based data regarding specific interventions for preventing burnout and reducing stress among physicians, particularly among psychiatrists.4

A randomized controlled trial of 74 practicing physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, evaluated the effectiveness of 19 biweekly physician-facilitated discussion groups.15 The groups covered topics such as elements of mindfulness, reflection, shared experience, and small-group learning. The institution provided 1 hour of paid time every other week for physicians to participate in this program. Physicians in the control group could schedule and use this time as they chose. Researchers also collected data on 350 non-trial participants.

The proportion of participants who strongly agreed that their work was meaningful increased 6.3% in the intervention group but decreased 6.3% in the control group and 13.4% among non-trial participants (P = .04).15 Rates of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention group, decreased slightly in the control group, and increased in the non-trial cohort. Results were sustained at 12 months after the study. There were no statistically significant differences in stress, symptoms of depression, overall quality of life, or job satisfaction.15

Preliminary evidence suggests that residents and fellows would find a wellness or suicide prevention program helpful. One study found that the use of one such program, which provided individual counseling, psychiatric evaluation, and wellness workshops for residents, fellows, and faculty in an academic health center, increased from 5% to 25% of eligible participants, and participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.16 Such programs would require institutional support for space and clinical staff.15

Empathy. As psychiatrists, we are taught to be empathetic. Yet, with the numerous challenges we face, it is not always easy. Stressors such as an increased workload or burnout can adversely affect a psychiatrist’s ability to provide empathetic care.17 However, empathetic treatment has clear benefits for both physicians and patients. Empathic skills can lead to more professional satisfaction and outcomes, which are important components of accountability, and can:

- promote patient satisfaction

- establish trust

- reduce anxiety

- increase adherence to treatment regimens

- improve health outcomes

- decrease the likelihood of malpractice suits.17

Mindfulness is a “flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context.”18,19 It may sound mundane to cling to phrases such as “living in the present,” but mindfulness can be a valuable tool for psychiatrists who struggle to maintain well-being in medicine’s challenging milieu. The process of mindfulness—actively drawing distinctions and noticing new things, “seeing the familiar in the novel and the novel in the familiar”—can ensure that we have active minds, that we are involved, and that we are capturing the joy of living in the stimulating present.18

Focus on issues you can control

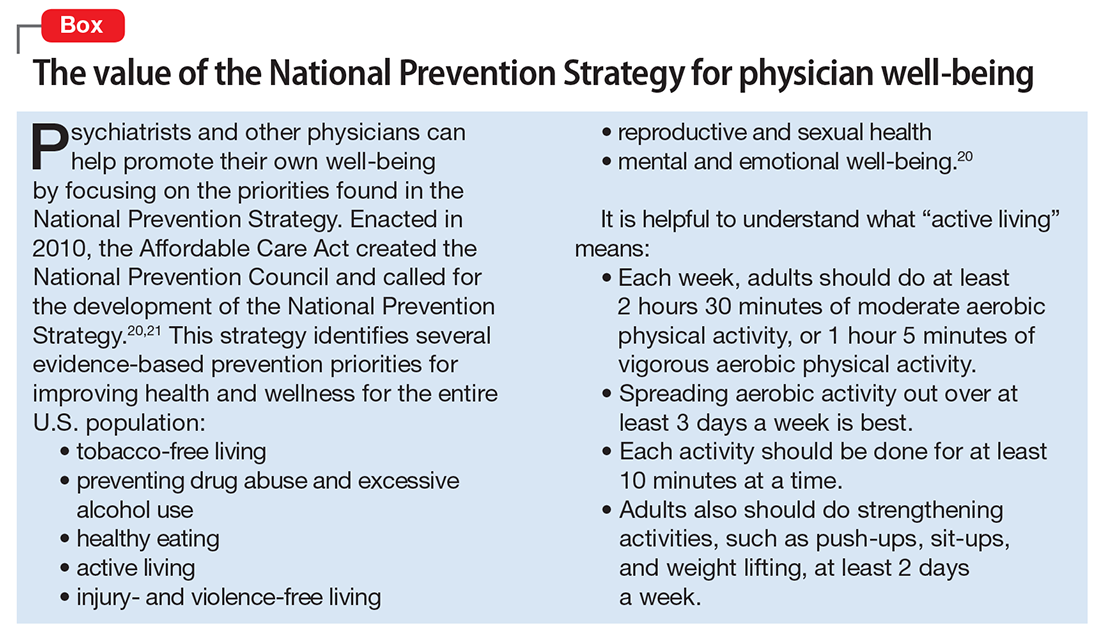

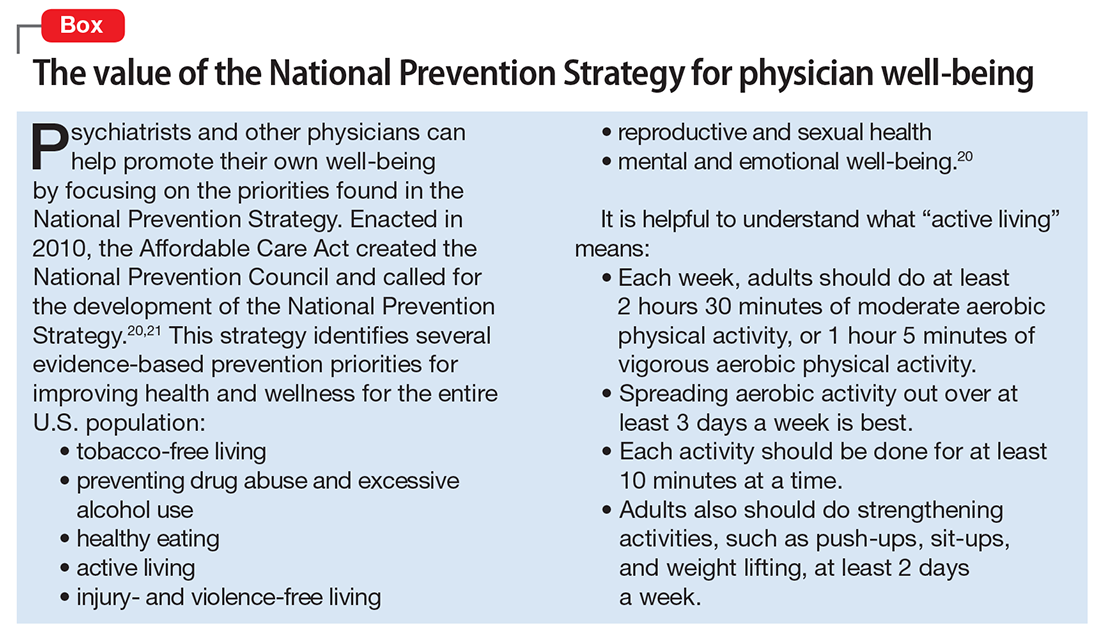

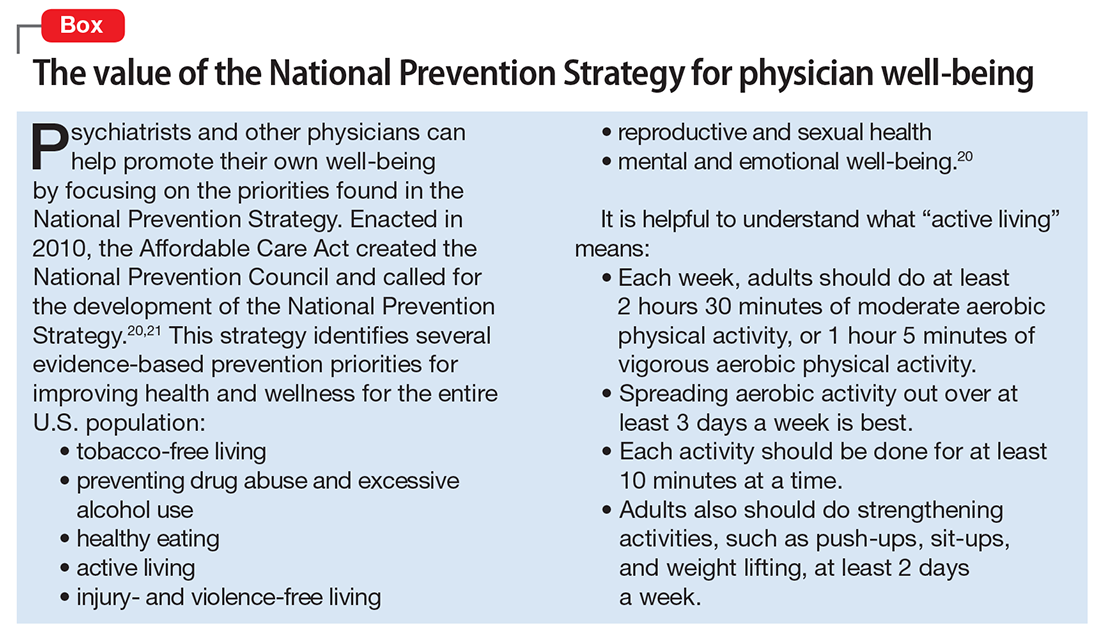

Many of the factors that negatively influence professional satisfaction and well-being, such as loss of autonomy, demand for increased patient care volume, and increasing scrutiny on the quality of care, are beyond a psychiatrist’s control. Medical administrators can help reduce some of these issues by increasing physician autonomy, offering physicians the opportunity to work part-time, offering medical staff workshops to enhance positive communication, or addressing leadership problems. However, psychiatrists may benefit most by identifying modifiable issues under their own control, such as prioritizing a work–life balance, applying the fundamentals of a health prevention strategy to their own lives (Box20,21), approaching medicine as a calling, embracing an empathetic approach to patient care, and bringing mindfulness to medical practice.

1. Goitein L. Physician well-being: addressing downstream effects, but looking upstream. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):533-534.

2. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

3. Kumar S. Burnout in psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):186-189.

4. Fothergill A, Edwards D, Burnard P. Stress, burnout, coping and stress management in psychiatrists: findings from a systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50(1):54-65.

5. Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, et al. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):104-110.

6. Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30-38.

7. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99-113.

8. Peckham C. Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle Report 2017: race and ethnicity, bias and burnout. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/psychiatry#page=1. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2017.

9. Holmes EG, Connolly A, Putnam KT, et al. Taking care of our own: a multispecialty study of resident and program director perspectives on contributors to burnout and potential interventions. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):159-166.

10. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

11. Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45-49.

12. Gold MS, Frost-Pineda K, Melker RJ. Physician suicide and drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1390; author reply 1390.

13. Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):167-173.

14. Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, et al. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: a survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:51-57.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

16. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

17. Newton BW. Walking a fine line: is it possible to remain an empathic physician and have a hardened heart? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:233.

18. Langer EJ. Mindful learning: current directions in psychological science. Am Psychological Society. 2000(6);9:220-223.

19. Crum AJ, Langer EJ. Mind-set matters: exercise and the placebo effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(2):165-171.

20. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. National Prevention Strategy. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/report.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed July 26, 2017.

21. Benjamin RM. The national prevention strategy: shifting the nation’s health-care system. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(6):774-776.

Like all physicians, psychiatrists practice in an increasingly complex health care environment, with escalating demands for productivity, rising threats of malpractice, expanding clinical oversight, and growing concerns about income. Additionally, psychiatric practice presents its own challenges, including limited resources and concerns about patient violence and suicide. These concerns can make it difficult to establish a healthy work–life balance.

Physicians, including psychiatrists, are at risk for alcohol or substance abuse/dependency, burnout, and suicide. As psychiatrists, we need to attend to our own personal and professional health so that we can best help our patients. This review focuses on the challenges psychiatrists face that can adversely affect their well-being and offers strategies to reduce the risk of burnout and enhance wellness.

The challenges of medicine and their impact on psychiatrists

The practice of medicine is inherently challenging. It requires hard work, discipline, dedication, and faithfulness to high ethical standards. Additional challenges include declining autonomy and opportunities for social support, increasing accountability, and a growing interest in reducing the cost of care by employing more non-physician health professionals—which in psychiatry typically include psychologists, nurse practitioners, and social workers. The uncertainty of the Affordable Care Act, declining income, and concerns about the nature of future medical practice are also stressors.1,2

Factors that contribute to psychiatrists’ stress include:

- limited resources

- concerns about patient violence and suicide

- crowded inpatient units

- changing culture in mental health services

- high work demands

- poorly defined roles of consultants

- declining authority

- frustration with the inability to impact systemic change

- conflict between responsibility toward employers vs the patient

- isolation.3

Concern about patient suicide is a significant stressor.4,5 Some evidence suggests that the impact of a patient’s suicide on a physician is more severe when it occurs during training than after graduation and is inversely correlated with the clinician’s perceived social integration into their professional network.5

Impediments to a physician’s well-being

Alcohol abuse/dependence. Approximately 13% of male physicians and 21% of female physicians meet Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Version C criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, according to a study of approximately 7,300 U.S. physicians from all specialties.6 (In this study, prescription drug abuse and use of illicit drugs were rare.) Age, hours worked, male sex, being married or partnered, having children, and being in a specialty other than internal medicine were independently associated with alcohol abuse or dependence.

Fortunately, psychiatrists were among the specialties with below average likelihood to meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse/dependency.6 However, alcohol abuse or dependency was associated with burnout, depression, suicidal ideation, lower quality of life, lower career satisfaction, and medical errors.

Burnout is a long-term stress reaction consisting of:

- physical and emotional exhaustion (feeling depleted)

- depersonalization (cynicism, lack of engagement with or negative attitudes toward patients)

- reduced sense of personal accomplishment (lack of a sense of purpose).7

In a 2017 survey of >14,000 U.S. physicians from 27 specialties, 42% of psychiatrists reported burnout.8 In another survey of approximately 300 resident physicians across all specialties in a tertiary academic hospital, 69% met criteria for burnout.9 This condition affects resident physicians as well as those in practice. Residents and program directors cited a lack of work–life balance and feeling unappreciated as factors contributing to burnout.

Among physicians, factors that contribute to burnout include loss of autonomy, diminished status as physicians, and increased work pressures. Burnout has a negative impact on both patients and health care systems. It is associated with an increased risk of depression and can contribute to:

- broken relationships

- alcohol abuse

- physician suicide

- decreased quality of care, including patient safety and satisfaction

- increased risk of malpractice suits

- reduced patient adherence to medical recommendations.5,10-12

Physicians who embrace medicine as a calling (ie, committing one’s life to personally meaningful work that serves a prosocial purpose) experience less burnout. According to a survey of approximately 900 primary care physicians and 300 psychiatrists, 42% of psychiatrists strongly agreed that medicine is a calling.13 Overall, physicians with a high sense of calling reported less burnout than those with a lower sense of calling (17% vs 31%, respectively).13

Depression and suicide. Gold et al12 analyzed a database that included information on approximately 31,600 adult suicide victims, and 203 of these victims were physicians. Compared with others, physicians were more likely to have a diagnosed mental illness or an occupation-related problem that contributed to suicide. Toxicology results also showed that physician suicide victims were significantly more likely than non-physician victims to test positive for benzodiazepines and barbiturates, but not antidepressants, which suggests that physicians with depression may not have been receiving adequate treatment.12

Although occupation-related stress and inadequate mental health treatment may be modifiable risk factors to reduce suicide deaths among physicians, stigma and fear of medical staff and licensure issues may deter physicians from seeking treatment.14

Steps to avoid burnout

Evidence-based interventions. There is limited evidence-based data regarding specific interventions for preventing burnout and reducing stress among physicians, particularly among psychiatrists.4

A randomized controlled trial of 74 practicing physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, evaluated the effectiveness of 19 biweekly physician-facilitated discussion groups.15 The groups covered topics such as elements of mindfulness, reflection, shared experience, and small-group learning. The institution provided 1 hour of paid time every other week for physicians to participate in this program. Physicians in the control group could schedule and use this time as they chose. Researchers also collected data on 350 non-trial participants.

The proportion of participants who strongly agreed that their work was meaningful increased 6.3% in the intervention group but decreased 6.3% in the control group and 13.4% among non-trial participants (P = .04).15 Rates of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention group, decreased slightly in the control group, and increased in the non-trial cohort. Results were sustained at 12 months after the study. There were no statistically significant differences in stress, symptoms of depression, overall quality of life, or job satisfaction.15

Preliminary evidence suggests that residents and fellows would find a wellness or suicide prevention program helpful. One study found that the use of one such program, which provided individual counseling, psychiatric evaluation, and wellness workshops for residents, fellows, and faculty in an academic health center, increased from 5% to 25% of eligible participants, and participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.16 Such programs would require institutional support for space and clinical staff.15

Empathy. As psychiatrists, we are taught to be empathetic. Yet, with the numerous challenges we face, it is not always easy. Stressors such as an increased workload or burnout can adversely affect a psychiatrist’s ability to provide empathetic care.17 However, empathetic treatment has clear benefits for both physicians and patients. Empathic skills can lead to more professional satisfaction and outcomes, which are important components of accountability, and can:

- promote patient satisfaction

- establish trust

- reduce anxiety

- increase adherence to treatment regimens

- improve health outcomes

- decrease the likelihood of malpractice suits.17

Mindfulness is a “flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context.”18,19 It may sound mundane to cling to phrases such as “living in the present,” but mindfulness can be a valuable tool for psychiatrists who struggle to maintain well-being in medicine’s challenging milieu. The process of mindfulness—actively drawing distinctions and noticing new things, “seeing the familiar in the novel and the novel in the familiar”—can ensure that we have active minds, that we are involved, and that we are capturing the joy of living in the stimulating present.18

Focus on issues you can control

Many of the factors that negatively influence professional satisfaction and well-being, such as loss of autonomy, demand for increased patient care volume, and increasing scrutiny on the quality of care, are beyond a psychiatrist’s control. Medical administrators can help reduce some of these issues by increasing physician autonomy, offering physicians the opportunity to work part-time, offering medical staff workshops to enhance positive communication, or addressing leadership problems. However, psychiatrists may benefit most by identifying modifiable issues under their own control, such as prioritizing a work–life balance, applying the fundamentals of a health prevention strategy to their own lives (Box20,21), approaching medicine as a calling, embracing an empathetic approach to patient care, and bringing mindfulness to medical practice.

Like all physicians, psychiatrists practice in an increasingly complex health care environment, with escalating demands for productivity, rising threats of malpractice, expanding clinical oversight, and growing concerns about income. Additionally, psychiatric practice presents its own challenges, including limited resources and concerns about patient violence and suicide. These concerns can make it difficult to establish a healthy work–life balance.

Physicians, including psychiatrists, are at risk for alcohol or substance abuse/dependency, burnout, and suicide. As psychiatrists, we need to attend to our own personal and professional health so that we can best help our patients. This review focuses on the challenges psychiatrists face that can adversely affect their well-being and offers strategies to reduce the risk of burnout and enhance wellness.

The challenges of medicine and their impact on psychiatrists

The practice of medicine is inherently challenging. It requires hard work, discipline, dedication, and faithfulness to high ethical standards. Additional challenges include declining autonomy and opportunities for social support, increasing accountability, and a growing interest in reducing the cost of care by employing more non-physician health professionals—which in psychiatry typically include psychologists, nurse practitioners, and social workers. The uncertainty of the Affordable Care Act, declining income, and concerns about the nature of future medical practice are also stressors.1,2

Factors that contribute to psychiatrists’ stress include:

- limited resources

- concerns about patient violence and suicide

- crowded inpatient units

- changing culture in mental health services

- high work demands

- poorly defined roles of consultants

- declining authority

- frustration with the inability to impact systemic change

- conflict between responsibility toward employers vs the patient

- isolation.3

Concern about patient suicide is a significant stressor.4,5 Some evidence suggests that the impact of a patient’s suicide on a physician is more severe when it occurs during training than after graduation and is inversely correlated with the clinician’s perceived social integration into their professional network.5

Impediments to a physician’s well-being

Alcohol abuse/dependence. Approximately 13% of male physicians and 21% of female physicians meet Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Version C criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, according to a study of approximately 7,300 U.S. physicians from all specialties.6 (In this study, prescription drug abuse and use of illicit drugs were rare.) Age, hours worked, male sex, being married or partnered, having children, and being in a specialty other than internal medicine were independently associated with alcohol abuse or dependence.

Fortunately, psychiatrists were among the specialties with below average likelihood to meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse/dependency.6 However, alcohol abuse or dependency was associated with burnout, depression, suicidal ideation, lower quality of life, lower career satisfaction, and medical errors.

Burnout is a long-term stress reaction consisting of:

- physical and emotional exhaustion (feeling depleted)

- depersonalization (cynicism, lack of engagement with or negative attitudes toward patients)

- reduced sense of personal accomplishment (lack of a sense of purpose).7

In a 2017 survey of >14,000 U.S. physicians from 27 specialties, 42% of psychiatrists reported burnout.8 In another survey of approximately 300 resident physicians across all specialties in a tertiary academic hospital, 69% met criteria for burnout.9 This condition affects resident physicians as well as those in practice. Residents and program directors cited a lack of work–life balance and feeling unappreciated as factors contributing to burnout.

Among physicians, factors that contribute to burnout include loss of autonomy, diminished status as physicians, and increased work pressures. Burnout has a negative impact on both patients and health care systems. It is associated with an increased risk of depression and can contribute to:

- broken relationships

- alcohol abuse

- physician suicide

- decreased quality of care, including patient safety and satisfaction

- increased risk of malpractice suits

- reduced patient adherence to medical recommendations.5,10-12

Physicians who embrace medicine as a calling (ie, committing one’s life to personally meaningful work that serves a prosocial purpose) experience less burnout. According to a survey of approximately 900 primary care physicians and 300 psychiatrists, 42% of psychiatrists strongly agreed that medicine is a calling.13 Overall, physicians with a high sense of calling reported less burnout than those with a lower sense of calling (17% vs 31%, respectively).13

Depression and suicide. Gold et al12 analyzed a database that included information on approximately 31,600 adult suicide victims, and 203 of these victims were physicians. Compared with others, physicians were more likely to have a diagnosed mental illness or an occupation-related problem that contributed to suicide. Toxicology results also showed that physician suicide victims were significantly more likely than non-physician victims to test positive for benzodiazepines and barbiturates, but not antidepressants, which suggests that physicians with depression may not have been receiving adequate treatment.12

Although occupation-related stress and inadequate mental health treatment may be modifiable risk factors to reduce suicide deaths among physicians, stigma and fear of medical staff and licensure issues may deter physicians from seeking treatment.14

Steps to avoid burnout

Evidence-based interventions. There is limited evidence-based data regarding specific interventions for preventing burnout and reducing stress among physicians, particularly among psychiatrists.4

A randomized controlled trial of 74 practicing physicians at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, evaluated the effectiveness of 19 biweekly physician-facilitated discussion groups.15 The groups covered topics such as elements of mindfulness, reflection, shared experience, and small-group learning. The institution provided 1 hour of paid time every other week for physicians to participate in this program. Physicians in the control group could schedule and use this time as they chose. Researchers also collected data on 350 non-trial participants.

The proportion of participants who strongly agreed that their work was meaningful increased 6.3% in the intervention group but decreased 6.3% in the control group and 13.4% among non-trial participants (P = .04).15 Rates of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention group, decreased slightly in the control group, and increased in the non-trial cohort. Results were sustained at 12 months after the study. There were no statistically significant differences in stress, symptoms of depression, overall quality of life, or job satisfaction.15

Preliminary evidence suggests that residents and fellows would find a wellness or suicide prevention program helpful. One study found that the use of one such program, which provided individual counseling, psychiatric evaluation, and wellness workshops for residents, fellows, and faculty in an academic health center, increased from 5% to 25% of eligible participants, and participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.16 Such programs would require institutional support for space and clinical staff.15

Empathy. As psychiatrists, we are taught to be empathetic. Yet, with the numerous challenges we face, it is not always easy. Stressors such as an increased workload or burnout can adversely affect a psychiatrist’s ability to provide empathetic care.17 However, empathetic treatment has clear benefits for both physicians and patients. Empathic skills can lead to more professional satisfaction and outcomes, which are important components of accountability, and can:

- promote patient satisfaction

- establish trust

- reduce anxiety

- increase adherence to treatment regimens

- improve health outcomes

- decrease the likelihood of malpractice suits.17

Mindfulness is a “flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context.”18,19 It may sound mundane to cling to phrases such as “living in the present,” but mindfulness can be a valuable tool for psychiatrists who struggle to maintain well-being in medicine’s challenging milieu. The process of mindfulness—actively drawing distinctions and noticing new things, “seeing the familiar in the novel and the novel in the familiar”—can ensure that we have active minds, that we are involved, and that we are capturing the joy of living in the stimulating present.18

Focus on issues you can control

Many of the factors that negatively influence professional satisfaction and well-being, such as loss of autonomy, demand for increased patient care volume, and increasing scrutiny on the quality of care, are beyond a psychiatrist’s control. Medical administrators can help reduce some of these issues by increasing physician autonomy, offering physicians the opportunity to work part-time, offering medical staff workshops to enhance positive communication, or addressing leadership problems. However, psychiatrists may benefit most by identifying modifiable issues under their own control, such as prioritizing a work–life balance, applying the fundamentals of a health prevention strategy to their own lives (Box20,21), approaching medicine as a calling, embracing an empathetic approach to patient care, and bringing mindfulness to medical practice.

1. Goitein L. Physician well-being: addressing downstream effects, but looking upstream. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):533-534.

2. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

3. Kumar S. Burnout in psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):186-189.

4. Fothergill A, Edwards D, Burnard P. Stress, burnout, coping and stress management in psychiatrists: findings from a systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50(1):54-65.

5. Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, et al. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):104-110.

6. Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30-38.

7. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99-113.

8. Peckham C. Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle Report 2017: race and ethnicity, bias and burnout. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/psychiatry#page=1. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2017.

9. Holmes EG, Connolly A, Putnam KT, et al. Taking care of our own: a multispecialty study of resident and program director perspectives on contributors to burnout and potential interventions. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):159-166.

10. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

11. Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45-49.

12. Gold MS, Frost-Pineda K, Melker RJ. Physician suicide and drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1390; author reply 1390.

13. Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):167-173.

14. Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, et al. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: a survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:51-57.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

16. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

17. Newton BW. Walking a fine line: is it possible to remain an empathic physician and have a hardened heart? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:233.

18. Langer EJ. Mindful learning: current directions in psychological science. Am Psychological Society. 2000(6);9:220-223.

19. Crum AJ, Langer EJ. Mind-set matters: exercise and the placebo effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(2):165-171.

20. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. National Prevention Strategy. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/report.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed July 26, 2017.

21. Benjamin RM. The national prevention strategy: shifting the nation’s health-care system. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(6):774-776.

1. Goitein L. Physician well-being: addressing downstream effects, but looking upstream. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):533-534.

2. Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1544-1552.

3. Kumar S. Burnout in psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):186-189.

4. Fothergill A, Edwards D, Burnard P. Stress, burnout, coping and stress management in psychiatrists: findings from a systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50(1):54-65.

5. Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, et al. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):104-110.

6. Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict. 2015;24(1):30-38.

7. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99-113.

8. Peckham C. Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle Report 2017: race and ethnicity, bias and burnout. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/psychiatry#page=1. Published January 11, 2017. Accessed July 25, 2017.

9. Holmes EG, Connolly A, Putnam KT, et al. Taking care of our own: a multispecialty study of resident and program director perspectives on contributors to burnout and potential interventions. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):159-166.

10. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

11. Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(1):45-49.

12. Gold MS, Frost-Pineda K, Melker RJ. Physician suicide and drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1390; author reply 1390.

13. Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):167-173.

14. Gold KJ, Andrew LB, Goldman EB, et al. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: a survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:51-57.

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

16. Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753.

17. Newton BW. Walking a fine line: is it possible to remain an empathic physician and have a hardened heart? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:233.

18. Langer EJ. Mindful learning: current directions in psychological science. Am Psychological Society. 2000(6);9:220-223.

19. Crum AJ, Langer EJ. Mind-set matters: exercise and the placebo effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(2):165-171.

20. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. National Prevention Strategy. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/report.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed July 26, 2017.

21. Benjamin RM. The national prevention strategy: shifting the nation’s health-care system. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(6):774-776.