User login

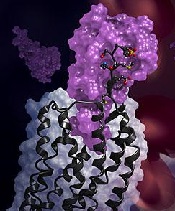

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()

in complex with a chemokine

(purple surface)

Credit: Katya Kadyshevskaya

Researchers have reported the first crystal structure of the cellular receptor CXCR4 bound to the viral chemokine antagonist vMIP-II.

The structure, published in Science, answers longstanding questions about a molecular interaction that plays an important role in human development, immune responses, cancer spread, and HIV infections.

“This new information could ultimately aid the development of better small molecular inhibitors of CXCR4-chemokine interactions—inhibitors that have the potential to block cancer metastasis or viral infections,” said study author Tracy M. Handel, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Handel and her colleagues knew that CXCR4 binds chemokines to transmit messages to the inside of the cell. This signal relay helps cells migrate normally during development and inflammation.

But CXCR4 signaling can also play a role in abnormal cell migration, such as when cancer cells metastasize. And CXCR4 is infamous for another reason: HIV uses it to bind and infect human immune cells.

Despite its far-reaching consequences, researchers have long lacked data to show how exactly the CXCR4-chemokine interaction occurs, or even how many CXCR4 receptors a single chemokine molecule might simultaneously engage.

This is because membrane receptors like CXCR4 are exceptionally challenging structural targets. And the difficulty dramatically increases when studying such receptors in complexes with the proteins they bind.

To overcome these experimental challenges, Dr Handel’s team used a novel approach. They combined computational modeling and a technique known as disulfide trapping to stabilize the complex.

Once it was stabilized, the researchers were able to use X-ray crystallography to determine the CXCR4-chemokine complex’s 3D atomic structure.

This is the first time a receptor like CXCR4 has been crystallized with a protein binding partner, and the results revealed several new insights. First, the new crystal structure shows that one chemokine binds to just one receptor.

Additionally, the structure reveals that the contacts between the receptor and its binding partner are more extensive than previously thought. It is one very large, contiguous surface of interaction rather than two separate binding sites.

“The plasticity of the CXCR4 receptor—its ability to bind many unrelated small molecules, peptides, and proteins—is remarkable,” said Irina Kufareva, PhD, also of UC San Diego.

“Our understanding of this plasticity may impact the design of therapeutics with better inhibition and safety profiles.”

“With more than 800 members, 7-transmembrane receptors like CXCR4 are the largest protein family in the human genome,” added Raymond Stevens, PhD, of the Bridge Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “Each new structure opens up so many doors to understanding different aspects of human biology, and this time it is about chemokine signaling.” ![]()