User login

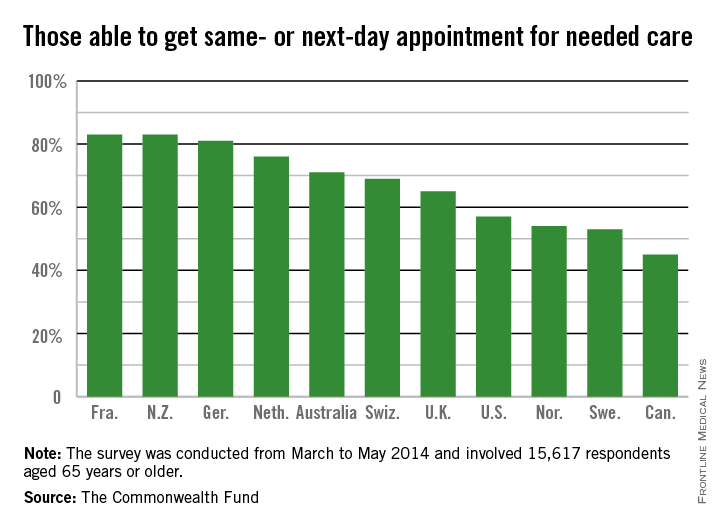

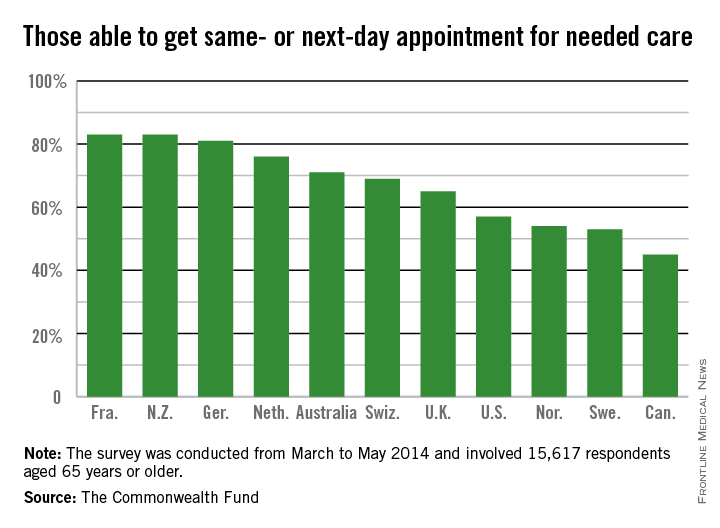

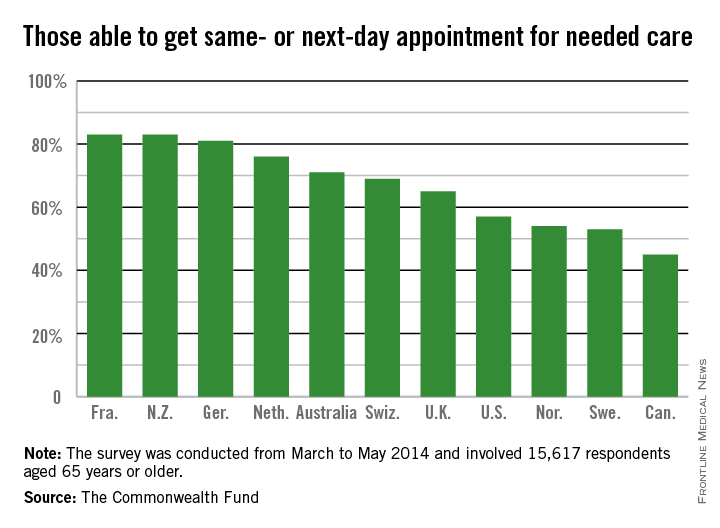

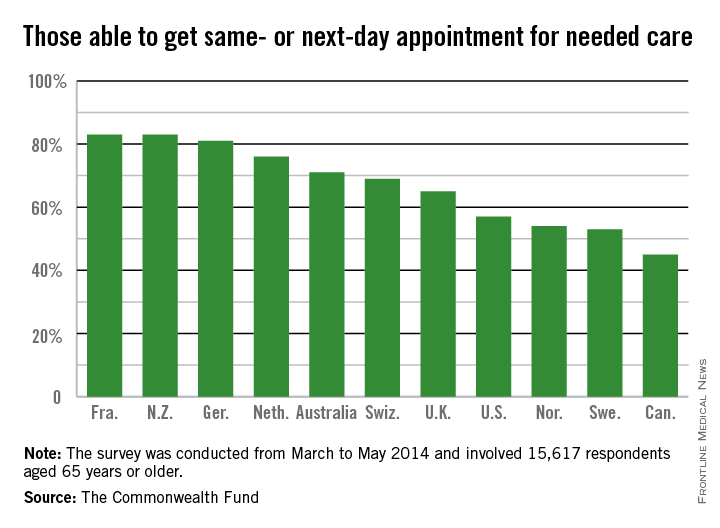

Older Americans are sicker than their peers in 11 developed countries, but are most likely to have a chronic care plan and to have discussed health-promoting behaviors with their physicians, according to a new survey.

The telephone survey analyzed responses from 15,617 adults over age 65 in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. It’s almost an apples-to-apples comparison because Medicare beneficiaries are considered fully insured, and all the other countries have some form of universal health coverage, lead author Robin Osborn said in a briefing on the study published Nov. 19 in the journal Health Affairs.

“This new survey shows that there are areas, such as managing patients who have chronic illnesses and hospital discharge planning, where the U.S. does well compared to other countries,” Ms. Osborn, vice president and director of the International Health Policy and Practice Innovations program at the Commonwealth Fund, said in a statement.

The United States also performed well when it came to patient-physician communication, transitions from the hospital to home, and end-of-life planning (Health. Aff. [doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0947]).

More than two-thirds (68%) of respondents in the United States had two or more chronic conditions, compared with 56% in Canada and 33% in the United Kingdom, which was at the low end of the spectrum.

The vast majority of patients in all countries reported that they thought their physician spent enough time with them, including 86% of Americans. Eighty-one percent of American patients said their physician encouraged them to ask questions – putting them on par with patients in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Germany, and Australia – compared with a low of 40% of patients in Norway.

Hospital discharge planning got high marks in the United States, with only 28% saying that they had any gaps in care after an inpatient stay. That compares with a high of around 70% of patients reporting problems in Sweden and Norway.

End-of-life planning was another area where it appears that the United States is doing better than other nations. Seventy-eight percent of U.S. patients said they had discussed their desires with a friend, family member, or physician, while 55% said they had a written advance directive, and 67% had a health care proxy.

By comparison, only 4% of Norwegians had an advance directive, and just 5% of French patients. Only Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom had rates near those seen in the United States.

Care coordination was a problem in all the nations surveyed. Older Americans were most likely to say that medical records or test results weren’t available at a scheduled appointment (23%) or that tests were duplicated. Patients in all nations reported receiving conflicting information from different doctors, and that primary care physicians did not speak with specialists, and vice versa.

The cost of care was a bigger issue for Americans than for patients in other countries. One in 5 (19%) of U.S. seniors had a medical problem but did not visit a doctor or skipped a test or refilling a prescription because of the cost. New Zealand was second, with 10% saying they had foregone treatment because of cost. Just 3% of French patients had cost issues.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Older Americans are sicker than their peers in 11 developed countries, but are most likely to have a chronic care plan and to have discussed health-promoting behaviors with their physicians, according to a new survey.

The telephone survey analyzed responses from 15,617 adults over age 65 in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. It’s almost an apples-to-apples comparison because Medicare beneficiaries are considered fully insured, and all the other countries have some form of universal health coverage, lead author Robin Osborn said in a briefing on the study published Nov. 19 in the journal Health Affairs.

“This new survey shows that there are areas, such as managing patients who have chronic illnesses and hospital discharge planning, where the U.S. does well compared to other countries,” Ms. Osborn, vice president and director of the International Health Policy and Practice Innovations program at the Commonwealth Fund, said in a statement.

The United States also performed well when it came to patient-physician communication, transitions from the hospital to home, and end-of-life planning (Health. Aff. [doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0947]).

More than two-thirds (68%) of respondents in the United States had two or more chronic conditions, compared with 56% in Canada and 33% in the United Kingdom, which was at the low end of the spectrum.

The vast majority of patients in all countries reported that they thought their physician spent enough time with them, including 86% of Americans. Eighty-one percent of American patients said their physician encouraged them to ask questions – putting them on par with patients in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Germany, and Australia – compared with a low of 40% of patients in Norway.

Hospital discharge planning got high marks in the United States, with only 28% saying that they had any gaps in care after an inpatient stay. That compares with a high of around 70% of patients reporting problems in Sweden and Norway.

End-of-life planning was another area where it appears that the United States is doing better than other nations. Seventy-eight percent of U.S. patients said they had discussed their desires with a friend, family member, or physician, while 55% said they had a written advance directive, and 67% had a health care proxy.

By comparison, only 4% of Norwegians had an advance directive, and just 5% of French patients. Only Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom had rates near those seen in the United States.

Care coordination was a problem in all the nations surveyed. Older Americans were most likely to say that medical records or test results weren’t available at a scheduled appointment (23%) or that tests were duplicated. Patients in all nations reported receiving conflicting information from different doctors, and that primary care physicians did not speak with specialists, and vice versa.

The cost of care was a bigger issue for Americans than for patients in other countries. One in 5 (19%) of U.S. seniors had a medical problem but did not visit a doctor or skipped a test or refilling a prescription because of the cost. New Zealand was second, with 10% saying they had foregone treatment because of cost. Just 3% of French patients had cost issues.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Older Americans are sicker than their peers in 11 developed countries, but are most likely to have a chronic care plan and to have discussed health-promoting behaviors with their physicians, according to a new survey.

The telephone survey analyzed responses from 15,617 adults over age 65 in the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. It’s almost an apples-to-apples comparison because Medicare beneficiaries are considered fully insured, and all the other countries have some form of universal health coverage, lead author Robin Osborn said in a briefing on the study published Nov. 19 in the journal Health Affairs.

“This new survey shows that there are areas, such as managing patients who have chronic illnesses and hospital discharge planning, where the U.S. does well compared to other countries,” Ms. Osborn, vice president and director of the International Health Policy and Practice Innovations program at the Commonwealth Fund, said in a statement.

The United States also performed well when it came to patient-physician communication, transitions from the hospital to home, and end-of-life planning (Health. Aff. [doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0947]).

More than two-thirds (68%) of respondents in the United States had two or more chronic conditions, compared with 56% in Canada and 33% in the United Kingdom, which was at the low end of the spectrum.

The vast majority of patients in all countries reported that they thought their physician spent enough time with them, including 86% of Americans. Eighty-one percent of American patients said their physician encouraged them to ask questions – putting them on par with patients in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Germany, and Australia – compared with a low of 40% of patients in Norway.

Hospital discharge planning got high marks in the United States, with only 28% saying that they had any gaps in care after an inpatient stay. That compares with a high of around 70% of patients reporting problems in Sweden and Norway.

End-of-life planning was another area where it appears that the United States is doing better than other nations. Seventy-eight percent of U.S. patients said they had discussed their desires with a friend, family member, or physician, while 55% said they had a written advance directive, and 67% had a health care proxy.

By comparison, only 4% of Norwegians had an advance directive, and just 5% of French patients. Only Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom had rates near those seen in the United States.

Care coordination was a problem in all the nations surveyed. Older Americans were most likely to say that medical records or test results weren’t available at a scheduled appointment (23%) or that tests were duplicated. Patients in all nations reported receiving conflicting information from different doctors, and that primary care physicians did not speak with specialists, and vice versa.

The cost of care was a bigger issue for Americans than for patients in other countries. One in 5 (19%) of U.S. seniors had a medical problem but did not visit a doctor or skipped a test or refilling a prescription because of the cost. New Zealand was second, with 10% saying they had foregone treatment because of cost. Just 3% of French patients had cost issues.

On Twitter @aliciaault

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS