User login

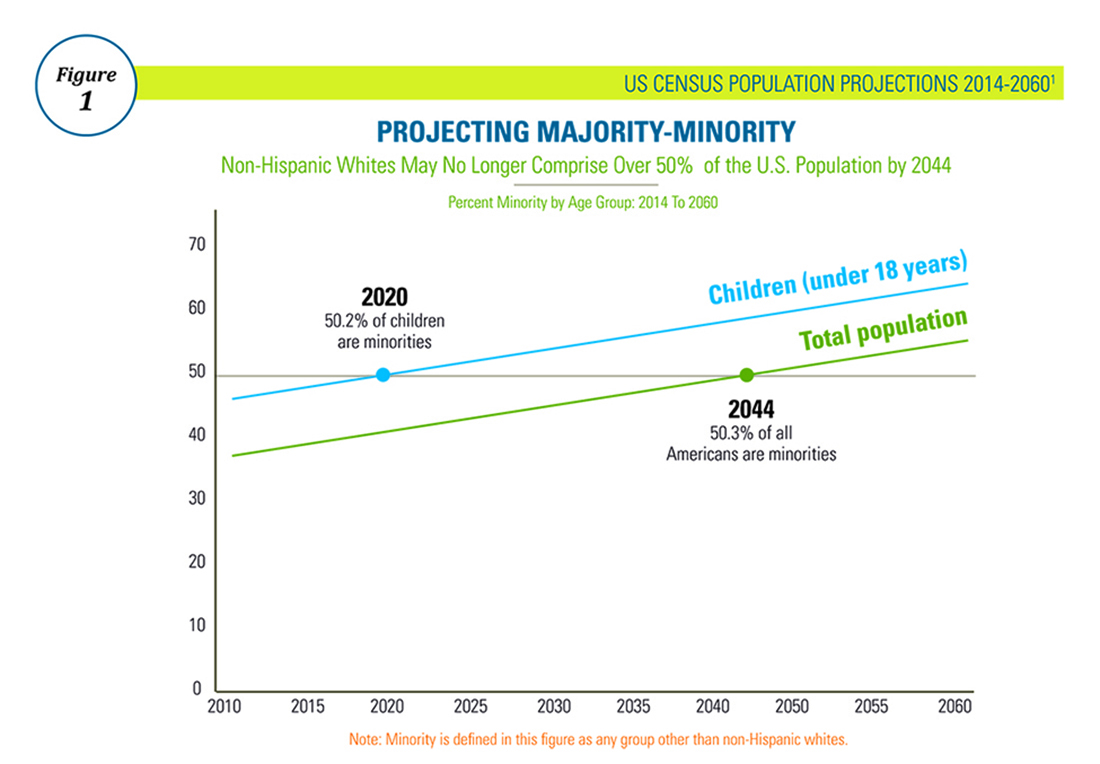

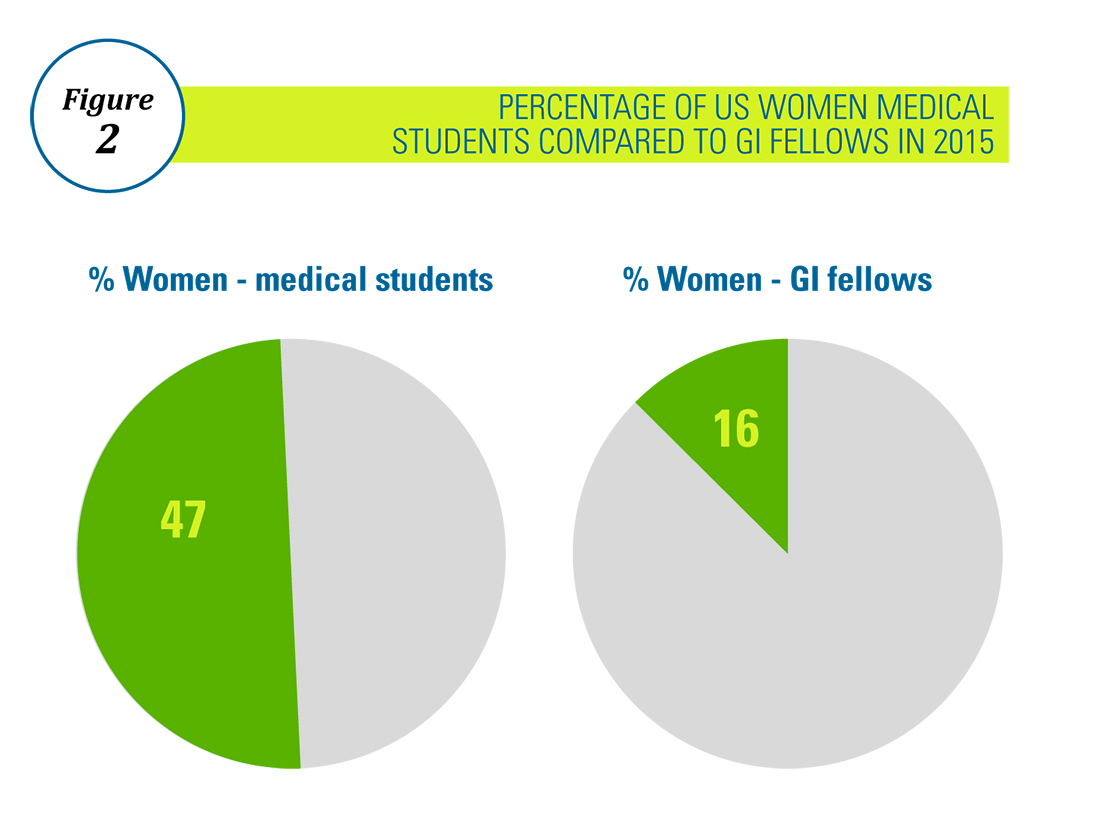

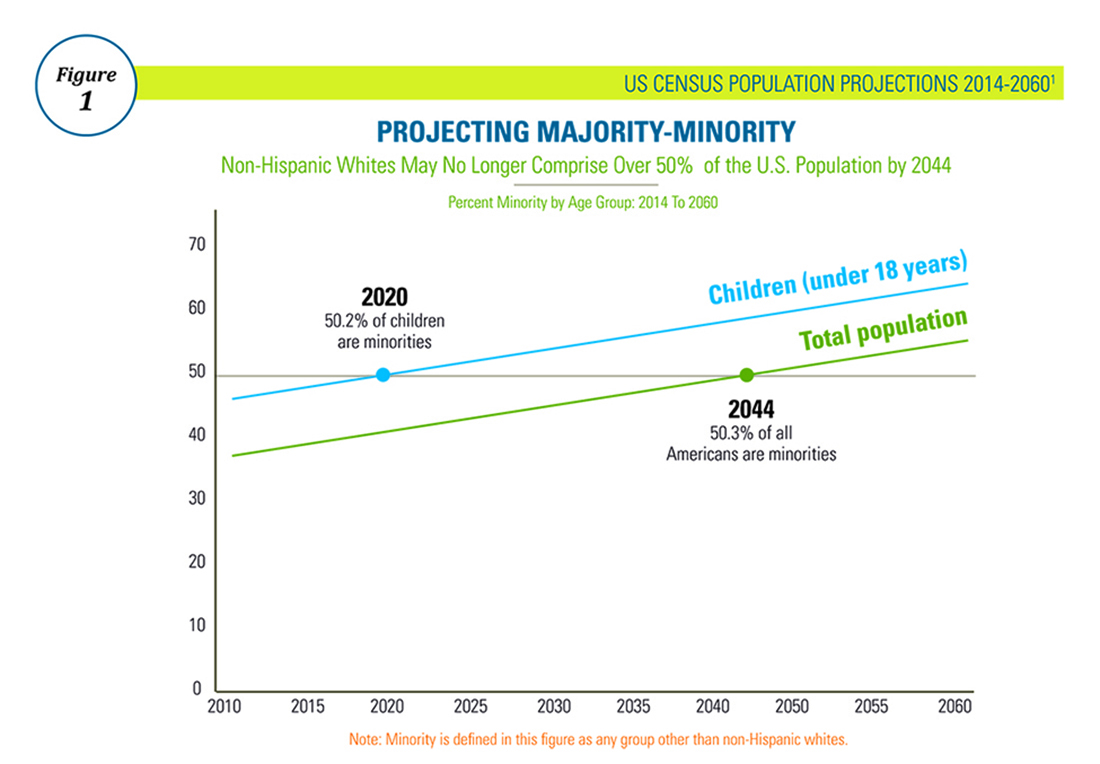

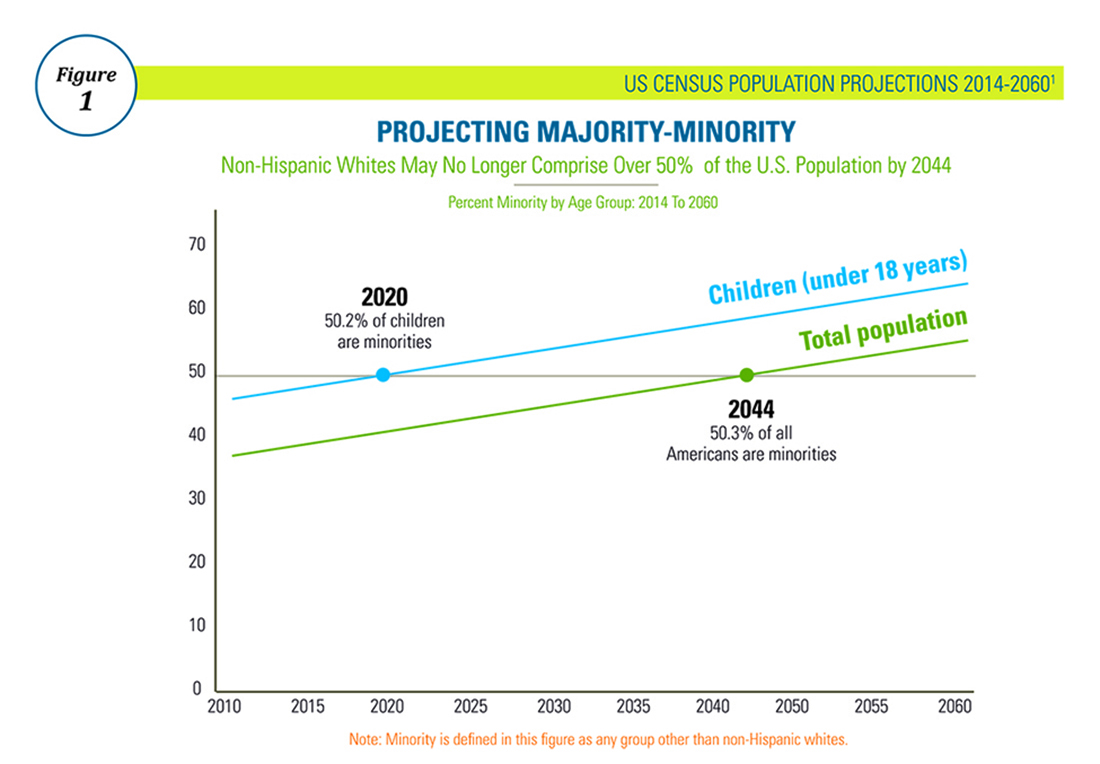

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.

There is no denying that practicing medicine calls us to serve a population that is diverse in many aspects. We live and work in a world that is evolving so quickly that medical workforce demographics fail to keep pace. In the U.S. in particular, racial and ethnic diversity has already exceeded many previous forecasts and will likely continue to do so.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recognizes that broader representation in the GI workforce requires increasing diversity at the trainee level and values this change for reasons beyond diversity for diversity’s sake. Based on education research, improving diversity at the trainee level helps learners thrive through the sharing of varied perspectives and enhancement of complex, critical thinking5. Moreover, diverse learning environments promote a culture of tolerance and understanding, tools needed to prepare trainees for future patient interactions. Diversity also translates into better patient satisfaction, as several studies have shown that physician-patient concordance on race, ethnicity, and gender result in higher patient satisfaction scores6. Additionally, minority physicians are more likely to practice in underserved areas and to conduct research addressing health care disparities, an area that will require an even greater investment as the U.S. population demographic continues to evolve3,7.

The AGA is committed to diversity, which is an inclusive concept that encompasses race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation, and disability. We strive to cultivate diversity within the organization at all levels, including governance, committee structure, staffing, and program and policy development. We are committed to the following goals intended to reflect the interests of the diverse patient population we serve:

1) Promotion of diversity within the practice of gastroenterology and in the individual care of patients of all backgrounds.

2) Recruitment and retention of GI providers and researchers from diverse backgrounds and the support of the advancement of their careers.

3) Elimination of disparities in GI diseases through community engagement, research, and advocacy.

Gastroenterology has been the most competitive fellowship specialty for the past 4 consecutive years, above pediatric surgery and cardiology8. We are privileged to practice an exciting, fascinating specialty that demands diversity of skill, acuity of care, and knowledge of pathophysiology. Increased diversity among those who research, teach, and practice in this wonderful field will only enhance it, and being mindful of this goal in our recruitment and retention efforts will help us achieve it.

For more information on the AGA Institute Diversity Committee and its ongoing initiatives, please visit http://www.gastro.org/about/people/committees/diversity-committee. Additionally, any specific enquiries should be addressed to Taylor Monson ([email protected]).

Dr. Quezeda is assistant dean for admissions, assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and a member of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee.

On behalf of the AGA Institute Diversity Committee: Rotonya M. Carr, MD (Chair, AGA Diversity Committee; assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), Karen A. Chachu, MD, PhD (assistant professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C.), Elizabeth Coss, MD (clinical assistant professor, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio), Maria Cruz-Correa, MD PhD (associate professor of medicine, biochemistry and surgery, University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center), Lukejohn Day, MD (associate clinical professor, University of California, San Francisco), Darrell M. Gray II, MD, MPH (assistant professor of medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), Esi Lamouse-Smith, MD, PhD (assistant professor of pediatrics, Columbia University, New York), Antonio Mendoza Ladd, MD (assistant professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso), and Celena NuQuay (AGA staff liaison).

References

1. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060 Population Estimates and Projections Current Population Reports. Colby S, Ortman JM. Issued March 2015.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Physician Specialty Databook, https://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/457712/2016-specialty-databook.html.

3. Association of American Medical Colleges Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts and Figures 2010.

4. Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R. Diversity in Graduate Medical Education in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-8.

5. Wells AS, Fox L, Cordova-Cobo D. How Racially Diverse Schools and Classrooms Can Benefit All Students. The Century Foundation, Feb 2016. https://tcf.org/content/report/how-racially-diverse-schools-and-classrooms-can-benefit-all-students/.

6. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Feb;19(2):101-10.

7. Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF et al. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008 Sep 10;300(10):1135-45.

8. Association of American Medical Colleges, ERAS Data. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/stats/359278/stats.html.