User login

Case

A 36-year-old woman with a 2-week history of left flank pain presented to the ED via emergency medical services. The patient, who had a history of nephrolithiasis, assumed her pain was due to another kidney stone. She stated that while waiting for the presumed stone to pass, the pain in her left flank worsened and she felt lightheaded and weak.

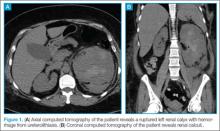

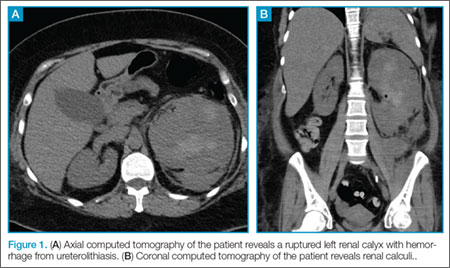

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: heart rate, 96 beats/minute; blood pressure, 133/76 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.9˚F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the patient had left lower quadrant pain and left costovertebral angle tenderness. Laboratory studies were remarkable for a negative urine pregnancy test, a hemoglobin level of 6.8 g/dL, and a hematocrit of 21.1%. Based on the patient’s history and symptoms, axial and coronal computed tomography (CT) scans were ordered, revealing a ruptured left renal calyx with hemorrhage from ureterolithiasis (Figures 1a and 1b).

Rupture of renal calyx and extravasation of blood or urine is a potential complication of nephrolithiasis. Stone size, degree of obstruction, and length of symptomatic presentation presumably contribute to complications from nephrolithiasis. Stones that are symptomatic for more than 4 weeks are estimated to have an increased complication rate of up to 20%.1

Calyx or fornix rupture results from increased intraluminal pressure. Rupture of these structures is thought to be a type of “safety-valve” function to relieve obstructive uropathy.2

Obstructions from small leaks to large urinomas can cause extravasation of urine. In most cases, urinary extravasation is confined to the subcapsular space or perirenal space within the Gerota’s fascia;3 however, as seen in this patient, mixed hematoma/urinomas can form.

Causes

In cases of nontraumatic calyx rupture, the cause of the obstruction is most often a distal obstructing ureteral stone.4 Other causes of rupture include extrinsic compression from malignant and benign masses, ureteric junction obstructions, or iatrogenic causes.4 Interestingly, in one small study, the median size of the obstructing stone was only 4 mm. The same study also noted that proximal ureteral obstruction occurred when larger stones where present.4

Conservative Versus Nonconservative Management

Potential complications of urinomas include abscess formation, sepsis, hydronephrosis, and paralytic ileus.3 Despite possible adverse sequelae, uncomplicated urinomas may be managed conservatively with supportive care. According to a study by Chapman et al,5 about 40% of patients managed conservatively recover without complications. In addition, in a retrospective study by Doehn et al6 involving 160 cases of fornix rupture treated with endoscopic therapy or nephrostomy tube supplemented with antibiotics, no instances of perinephric abscess or other complications requiring a second procedure were noted.

Management of suspected ureterolithiasis in the ED is focused on analgesia and supportive care. Acute analgesia is often provided parenterally with opioids alone or with an opioid/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) combination.7 Frequent reassessment of the patient is required to ensure adequate pain control and to prevent sedation. Other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, may be treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and antiemetic medications. Further radiographic evaluation is needed once analgesia is achieved.7,8

Imaging Studies

Radiological evaluation of patients with suspected ureterolithiasis may involve several imaging modalities. Noncontrast helical CT scan is the standard for rapid and efficient identification of ureteral stones while allowing visualization of other potential pathology (eg, urinoma).7-9 Other modalities, such as ultrasonography; radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder; and an IV pyelogram with contrasted CT, may be ordered if noncontrast helical CT scan is not available on-site or if there are comorbidities. In addition to imaging studies, basic laboratory studies (eg, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen testing) are indicated to assess overall renal function and direct the choice of radiological study.7

Disposition

Clinical decision-making is key when recommending inpatient versus outpatient treatment in patients with ureterolithiasis. Patients with uncontrolled pain or vomiting may require inpatient admission for supportive care, while those demonstrating acute renal failure, pyuria with bacteriuria, complete bilateral ureteral obstruction, urinoma, or signs of sepsis demand emergent urology consultation. Specifically, patients with urinoma require ureteroscopy versus nephrostomy6,10 to allow drainage while carefully monitoring for development of subsequent bleeding and infection.

When discharging patients from the ED, expulsive therapy using tamsulosin9 and analgesia with combination of oral opioids and NSAIDs are most commonly effective.11 Outpatient urology referrals are recommended for ureteral stones greater than 5 mm in size or if the stones have been present in the ureter for greater than 4 weeks.1 Proper evaluation and management of ureterolithiasis in the ED is crucial for positive outcomes and to reduce long-term complications.

Case Conclusion

Computed tomography revealed a ruptured renal calyx on the left side with free fluid in the abdomen. Urology services were consulted and the patient was taken to the operating room for cystoscopy, ureteral stent placement, and laser lithotripsy. Following surgery, she subsequently developed urosepsis for which she was successfully treated with IV antibiotics and discharged on hospital day 15.

Mr Eisenstat is a fourth-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville. Dr Fabiano is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina. Dr Collins is family medicine physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina.

- Hübner WA, Irby P, Stoller M. Natural history and current concepts for the treatment of small ureteral calculi. Eur Urol. 1993;24(2):172-176.

- Lin DY, Fang YC, Huang DY, Lin SP. Spontaneous rupture of the ureter secondary to urolithiasis and extravasation of calyceal fornix due to acute urinary bladder distension: four case reports. Chin J Radiology. 2004;29:269-275.

- Behzad-Noori M, Blandon JA, Negrin Exposito JE, Sarmiento JL, Dias AL, Hernandez GT. Urinoma: a rare complication from being between a rock and soft organ. El Paso Physician. 2010;33(6):5-6.

- Gershman B, Kulkarni N, Sahani DV, Eisner BH. Causes of renal forniceal rupture. BJU Int. 2011;108(11):1909-1911.

- Chapman JP, Gonzalez J, Diokno AC. Significance of urinary extravasation during renal colic. Urology. 1987;30(6):541-545.

- Doehn C, Fiola L, Peter M, Jocham D. Outcome analysis of fornix ruptures in 162 consecutive patients. J Endourol. 2010;24(11):1869-1873

- Portis AJ, Sundaram CP. Diagnosis and initial management of kidney stones. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(7):1329-1338

- Smith RC, Verga M, Dalrymple N, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT. Acute ureteral obstruction: value of secondary signs of helical unenhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(5):1109-1113.Burke TA, Wisniewski T, Ernst FR. Resource utilization and costs associated with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy administered in the US outpatient hospital setting. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):131-140.

- Ha M, MacDonald RD. Impact of CT scan in patients with first episode of suspected nephrolithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(3):225-231.

- Tawfiek ER, Bagley DH. Management of upper urinary tract calculi with ureteroscopic techniques. Urology. 1999;53(1):25-31.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D'Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.

Case

A 36-year-old woman with a 2-week history of left flank pain presented to the ED via emergency medical services. The patient, who had a history of nephrolithiasis, assumed her pain was due to another kidney stone. She stated that while waiting for the presumed stone to pass, the pain in her left flank worsened and she felt lightheaded and weak.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: heart rate, 96 beats/minute; blood pressure, 133/76 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.9˚F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the patient had left lower quadrant pain and left costovertebral angle tenderness. Laboratory studies were remarkable for a negative urine pregnancy test, a hemoglobin level of 6.8 g/dL, and a hematocrit of 21.1%. Based on the patient’s history and symptoms, axial and coronal computed tomography (CT) scans were ordered, revealing a ruptured left renal calyx with hemorrhage from ureterolithiasis (Figures 1a and 1b).

Rupture of renal calyx and extravasation of blood or urine is a potential complication of nephrolithiasis. Stone size, degree of obstruction, and length of symptomatic presentation presumably contribute to complications from nephrolithiasis. Stones that are symptomatic for more than 4 weeks are estimated to have an increased complication rate of up to 20%.1

Calyx or fornix rupture results from increased intraluminal pressure. Rupture of these structures is thought to be a type of “safety-valve” function to relieve obstructive uropathy.2

Obstructions from small leaks to large urinomas can cause extravasation of urine. In most cases, urinary extravasation is confined to the subcapsular space or perirenal space within the Gerota’s fascia;3 however, as seen in this patient, mixed hematoma/urinomas can form.

Causes

In cases of nontraumatic calyx rupture, the cause of the obstruction is most often a distal obstructing ureteral stone.4 Other causes of rupture include extrinsic compression from malignant and benign masses, ureteric junction obstructions, or iatrogenic causes.4 Interestingly, in one small study, the median size of the obstructing stone was only 4 mm. The same study also noted that proximal ureteral obstruction occurred when larger stones where present.4

Conservative Versus Nonconservative Management

Potential complications of urinomas include abscess formation, sepsis, hydronephrosis, and paralytic ileus.3 Despite possible adverse sequelae, uncomplicated urinomas may be managed conservatively with supportive care. According to a study by Chapman et al,5 about 40% of patients managed conservatively recover without complications. In addition, in a retrospective study by Doehn et al6 involving 160 cases of fornix rupture treated with endoscopic therapy or nephrostomy tube supplemented with antibiotics, no instances of perinephric abscess or other complications requiring a second procedure were noted.

Management of suspected ureterolithiasis in the ED is focused on analgesia and supportive care. Acute analgesia is often provided parenterally with opioids alone or with an opioid/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) combination.7 Frequent reassessment of the patient is required to ensure adequate pain control and to prevent sedation. Other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, may be treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and antiemetic medications. Further radiographic evaluation is needed once analgesia is achieved.7,8

Imaging Studies

Radiological evaluation of patients with suspected ureterolithiasis may involve several imaging modalities. Noncontrast helical CT scan is the standard for rapid and efficient identification of ureteral stones while allowing visualization of other potential pathology (eg, urinoma).7-9 Other modalities, such as ultrasonography; radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder; and an IV pyelogram with contrasted CT, may be ordered if noncontrast helical CT scan is not available on-site or if there are comorbidities. In addition to imaging studies, basic laboratory studies (eg, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen testing) are indicated to assess overall renal function and direct the choice of radiological study.7

Disposition

Clinical decision-making is key when recommending inpatient versus outpatient treatment in patients with ureterolithiasis. Patients with uncontrolled pain or vomiting may require inpatient admission for supportive care, while those demonstrating acute renal failure, pyuria with bacteriuria, complete bilateral ureteral obstruction, urinoma, or signs of sepsis demand emergent urology consultation. Specifically, patients with urinoma require ureteroscopy versus nephrostomy6,10 to allow drainage while carefully monitoring for development of subsequent bleeding and infection.

When discharging patients from the ED, expulsive therapy using tamsulosin9 and analgesia with combination of oral opioids and NSAIDs are most commonly effective.11 Outpatient urology referrals are recommended for ureteral stones greater than 5 mm in size or if the stones have been present in the ureter for greater than 4 weeks.1 Proper evaluation and management of ureterolithiasis in the ED is crucial for positive outcomes and to reduce long-term complications.

Case Conclusion

Computed tomography revealed a ruptured renal calyx on the left side with free fluid in the abdomen. Urology services were consulted and the patient was taken to the operating room for cystoscopy, ureteral stent placement, and laser lithotripsy. Following surgery, she subsequently developed urosepsis for which she was successfully treated with IV antibiotics and discharged on hospital day 15.

Mr Eisenstat is a fourth-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville. Dr Fabiano is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina. Dr Collins is family medicine physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina.

Case

A 36-year-old woman with a 2-week history of left flank pain presented to the ED via emergency medical services. The patient, who had a history of nephrolithiasis, assumed her pain was due to another kidney stone. She stated that while waiting for the presumed stone to pass, the pain in her left flank worsened and she felt lightheaded and weak.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: heart rate, 96 beats/minute; blood pressure, 133/76 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.9˚F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the patient had left lower quadrant pain and left costovertebral angle tenderness. Laboratory studies were remarkable for a negative urine pregnancy test, a hemoglobin level of 6.8 g/dL, and a hematocrit of 21.1%. Based on the patient’s history and symptoms, axial and coronal computed tomography (CT) scans were ordered, revealing a ruptured left renal calyx with hemorrhage from ureterolithiasis (Figures 1a and 1b).

Rupture of renal calyx and extravasation of blood or urine is a potential complication of nephrolithiasis. Stone size, degree of obstruction, and length of symptomatic presentation presumably contribute to complications from nephrolithiasis. Stones that are symptomatic for more than 4 weeks are estimated to have an increased complication rate of up to 20%.1

Calyx or fornix rupture results from increased intraluminal pressure. Rupture of these structures is thought to be a type of “safety-valve” function to relieve obstructive uropathy.2

Obstructions from small leaks to large urinomas can cause extravasation of urine. In most cases, urinary extravasation is confined to the subcapsular space or perirenal space within the Gerota’s fascia;3 however, as seen in this patient, mixed hematoma/urinomas can form.

Causes

In cases of nontraumatic calyx rupture, the cause of the obstruction is most often a distal obstructing ureteral stone.4 Other causes of rupture include extrinsic compression from malignant and benign masses, ureteric junction obstructions, or iatrogenic causes.4 Interestingly, in one small study, the median size of the obstructing stone was only 4 mm. The same study also noted that proximal ureteral obstruction occurred when larger stones where present.4

Conservative Versus Nonconservative Management

Potential complications of urinomas include abscess formation, sepsis, hydronephrosis, and paralytic ileus.3 Despite possible adverse sequelae, uncomplicated urinomas may be managed conservatively with supportive care. According to a study by Chapman et al,5 about 40% of patients managed conservatively recover without complications. In addition, in a retrospective study by Doehn et al6 involving 160 cases of fornix rupture treated with endoscopic therapy or nephrostomy tube supplemented with antibiotics, no instances of perinephric abscess or other complications requiring a second procedure were noted.

Management of suspected ureterolithiasis in the ED is focused on analgesia and supportive care. Acute analgesia is often provided parenterally with opioids alone or with an opioid/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) combination.7 Frequent reassessment of the patient is required to ensure adequate pain control and to prevent sedation. Other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and dehydration, may be treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and antiemetic medications. Further radiographic evaluation is needed once analgesia is achieved.7,8

Imaging Studies

Radiological evaluation of patients with suspected ureterolithiasis may involve several imaging modalities. Noncontrast helical CT scan is the standard for rapid and efficient identification of ureteral stones while allowing visualization of other potential pathology (eg, urinoma).7-9 Other modalities, such as ultrasonography; radiography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder; and an IV pyelogram with contrasted CT, may be ordered if noncontrast helical CT scan is not available on-site or if there are comorbidities. In addition to imaging studies, basic laboratory studies (eg, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen testing) are indicated to assess overall renal function and direct the choice of radiological study.7

Disposition

Clinical decision-making is key when recommending inpatient versus outpatient treatment in patients with ureterolithiasis. Patients with uncontrolled pain or vomiting may require inpatient admission for supportive care, while those demonstrating acute renal failure, pyuria with bacteriuria, complete bilateral ureteral obstruction, urinoma, or signs of sepsis demand emergent urology consultation. Specifically, patients with urinoma require ureteroscopy versus nephrostomy6,10 to allow drainage while carefully monitoring for development of subsequent bleeding and infection.

When discharging patients from the ED, expulsive therapy using tamsulosin9 and analgesia with combination of oral opioids and NSAIDs are most commonly effective.11 Outpatient urology referrals are recommended for ureteral stones greater than 5 mm in size or if the stones have been present in the ureter for greater than 4 weeks.1 Proper evaluation and management of ureterolithiasis in the ED is crucial for positive outcomes and to reduce long-term complications.

Case Conclusion

Computed tomography revealed a ruptured renal calyx on the left side with free fluid in the abdomen. Urology services were consulted and the patient was taken to the operating room for cystoscopy, ureteral stent placement, and laser lithotripsy. Following surgery, she subsequently developed urosepsis for which she was successfully treated with IV antibiotics and discharged on hospital day 15.

Mr Eisenstat is a fourth-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville. Dr Fabiano is an emergency physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina. Dr Collins is family medicine physician, department of emergency medicine, Greenville Health Systems, Greenville, South Carolina.

- Hübner WA, Irby P, Stoller M. Natural history and current concepts for the treatment of small ureteral calculi. Eur Urol. 1993;24(2):172-176.

- Lin DY, Fang YC, Huang DY, Lin SP. Spontaneous rupture of the ureter secondary to urolithiasis and extravasation of calyceal fornix due to acute urinary bladder distension: four case reports. Chin J Radiology. 2004;29:269-275.

- Behzad-Noori M, Blandon JA, Negrin Exposito JE, Sarmiento JL, Dias AL, Hernandez GT. Urinoma: a rare complication from being between a rock and soft organ. El Paso Physician. 2010;33(6):5-6.

- Gershman B, Kulkarni N, Sahani DV, Eisner BH. Causes of renal forniceal rupture. BJU Int. 2011;108(11):1909-1911.

- Chapman JP, Gonzalez J, Diokno AC. Significance of urinary extravasation during renal colic. Urology. 1987;30(6):541-545.

- Doehn C, Fiola L, Peter M, Jocham D. Outcome analysis of fornix ruptures in 162 consecutive patients. J Endourol. 2010;24(11):1869-1873

- Portis AJ, Sundaram CP. Diagnosis and initial management of kidney stones. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(7):1329-1338

- Smith RC, Verga M, Dalrymple N, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT. Acute ureteral obstruction: value of secondary signs of helical unenhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(5):1109-1113.Burke TA, Wisniewski T, Ernst FR. Resource utilization and costs associated with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy administered in the US outpatient hospital setting. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):131-140.

- Ha M, MacDonald RD. Impact of CT scan in patients with first episode of suspected nephrolithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(3):225-231.

- Tawfiek ER, Bagley DH. Management of upper urinary tract calculi with ureteroscopic techniques. Urology. 1999;53(1):25-31.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D'Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.

- Hübner WA, Irby P, Stoller M. Natural history and current concepts for the treatment of small ureteral calculi. Eur Urol. 1993;24(2):172-176.

- Lin DY, Fang YC, Huang DY, Lin SP. Spontaneous rupture of the ureter secondary to urolithiasis and extravasation of calyceal fornix due to acute urinary bladder distension: four case reports. Chin J Radiology. 2004;29:269-275.

- Behzad-Noori M, Blandon JA, Negrin Exposito JE, Sarmiento JL, Dias AL, Hernandez GT. Urinoma: a rare complication from being between a rock and soft organ. El Paso Physician. 2010;33(6):5-6.

- Gershman B, Kulkarni N, Sahani DV, Eisner BH. Causes of renal forniceal rupture. BJU Int. 2011;108(11):1909-1911.

- Chapman JP, Gonzalez J, Diokno AC. Significance of urinary extravasation during renal colic. Urology. 1987;30(6):541-545.

- Doehn C, Fiola L, Peter M, Jocham D. Outcome analysis of fornix ruptures in 162 consecutive patients. J Endourol. 2010;24(11):1869-1873

- Portis AJ, Sundaram CP. Diagnosis and initial management of kidney stones. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(7):1329-1338

- Smith RC, Verga M, Dalrymple N, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT. Acute ureteral obstruction: value of secondary signs of helical unenhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(5):1109-1113.Burke TA, Wisniewski T, Ernst FR. Resource utilization and costs associated with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) following highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy administered in the US outpatient hospital setting. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):131-140.

- Ha M, MacDonald RD. Impact of CT scan in patients with first episode of suspected nephrolithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(3):225-231.

- Tawfiek ER, Bagley DH. Management of upper urinary tract calculi with ureteroscopic techniques. Urology. 1999;53(1):25-31.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D'Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.