User login

› Ask Asian immigrants open-ended questions and encourage them to share their use of alternative remedies. C

› Consider providing an interpretation service for patients not proficient in English, as opposed to asking family members to help. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Though often considered a “model minority,” Asian immigrants pose significant challenges for Western health care providers, including radically different ideas of disease causation, differing communication styles, and somatic presentations of mental illness. Asian diversity is tremendous, but several cultural trends are held in common: strong family structures, respect, adaptability, and, for first generation immigrants, widespread use of traditional therapies.1

While Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs) represent only 5.6% of the US population, or 17.3 million people, that figure represents a 46% increase between 2000 and 2010, the most rapid for any ethnic group.2 A 79% increase is anticipated by 2050, bringing Asians to 9.3% of the US population. In order of population, API subpopulations include Chinese, Filipinos, Asian Indians, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese.2 More than half of Asian Americans reside in the states of California, New York, and Hawaii, although enclaves exist in most major cities.3

Addressing the health needs of Asian immigrants in an increasingly diverse society mandates that US physicians develop the necessary skills to communicate, even when expectations for care may be very different. Fortunately, excellent resources are available (TABLE 1).

Barriers to good healthcare

The most formidable obstacle is limited English proficiency of patients, making them significantly less likely to seek care.4 They often struggle to arrange an appointment, although they arrive on time.5

Inadequate interpretation services. Frequently family members must interpret for patients, despite a federal mandate (Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) requiring professional services be provided at no charge if there is a federal payer (Medicare or Medicaid) involved.6 Unfortunately, these services are not currently reimbursable. Use of family or friends as interpreters, while convenient, results in far less accurate interpretation, frequent embarrassment, and loss of patient confidentiality. Trained medical interpreters or even telephone services are preferable, as they are much more accurate. Interviews involve a triad comprised of provider, patient, and interpreter, with the provider speaking directly to the patient using first-person address at all times. The interpreter should sit to the side or slightly behind the patient. All communication should be interpreted sentence by sentence so everyone is able to understand the entire conversation. It is well documented that proper interpretive services vastly improve the quality of care.7

Patient illiteracy. Health care illiteracy leads to medication errors due to the inability to understand instructions.8 Some immigrants have the added disadvantage of being illiterate both in English and in their native tongue.4 If not remedied, these situations easily lead to drug overdoses or missed allergies.9 Older immigrants neither understand the intricacies of the US health care system nor possess the language skills to master it.4

Stereotyping by caregivers must be surmounted if patients are to receive quality care. Many Asian patients report that physicians fail to understand them as unique individuals apart from their ethnic identity. Others feel excluded from the decision-making process or find culturally sensitive treatment options lacking.10

Subtleties of relational interaction. Asian culture has been defined as possessing a high Power Distance Index (PDI).11 The PDI refers to the distance or level of respect which an individual must afford to a superior, and this ideal is reflected in Asian conformance to a strict social hierarchy. Thus, physicians are viewed as authority figures and it is proper to nod or smile to indicate polite deference.12 However, showing respect and “buying in” to treatment recommendations are entirely different matters. Cultural factors make it difficult for patients to openly disagree with physician recommendations without feeling as though they have been disrespectful.12 Asian cultures are also “high context” cultures, having far more unwritten rules for conduct and communication that often prove baffling to westerners from “lower context” cultures.

Financial limitations. Socioeconomic influences also play a role. Although Asians have a higher income than other minority groups, 12.5% of Asians still live in poverty and 17.2% lack health insurance.2 Lack of coverage makes many Asians reluctant to seek regular medical care.13

Special medical concerns

Asian-Americans face a variety of challenging medical issues, including disproportionately high rates of tuberculosis (TB) and hepatitis B.

TB. Although rates of TB infection in the United States are low, rates in Asian immigrants are up to 100 times greater than that of the general population, more than any other immigrant group.14 Screening with interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs), such as T-SPOT TB, should be routine for Asian immigrants, since IGRAs do not cross-react with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends IGRA blood testing in lieu of tuberculin skin testing (TST) for immigrants who received BCG in infancy, with the exception of children <5 years, for whom the TST is still preferable.15 Patients with positive IGRA tests are also more likely to be amenable to treatment.

Chronic hepatitis B infection in Asian immigrants is often due to perinatal transmission in their home countries. Rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the United States have been steadily declining since vaccination began in 1981. However, chronic HBV infection in Asian immigrants approaches 10% of that population.16 An estimated 15% to 20% of patients with chronic HBV develop cirrhosis within 5 years and are at high risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).17,18

Evaluate HBV carriers annually with liver function testing (LFTs), hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis B e-Antigen (HBeAg). A positive HBsAg result indicates the virus is present; a positive HBeAg result indicates the virus is actively replicating. LFT elevation (AST >200 IU/L) or a positive HBeAg test should prompt referral to a gastroenterologist for liver biopsy and therapy. Screening for HCC with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and liver ultrasounds every 6 to 12 months has been recommended for all chronic HBV carriers,19 but this interval remains controversial. Screen men ≥40 years and women ≥50, or anyone who has had HBV infection >10 years, every 6 months.19,20 More recent recommendations favor ultrasound over AFP for screening, as the latter test lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity.20 Test partners and family members of HBV patients, and vaccinate them against HBV if not already immune.

Other medical issues. Asians from the Indian subcontinent have a significantly elevated risk of heart disease, in part due to low HDL-cholesterol levels.21 South Asian immigrant populations have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death compared with other ethnicities, and often exhibit coronary disease before the age of 40.22 The recent adoption of a Western diet and sedentary lifestyle has provoked an epidemic of diabetes throughout urban Asia and in Asians living abroad. This may be related to the “thrifty gene hypothesis,” which suggests that genes which evolved early in human history to facilitate storage of fat for periods of famine are detrimental in modern society where food is plentiful. A study of Asian Indian immigrants in Atlanta demonstrated an 18.3% prevalence rate for diabetes, higher than any other ethnic group.23 Tobacco and its causal relationship with lung cancer and heart disease only adds to this concern. Southeast Asians in particular demonstrate alarmingly high rates of tobacco consumption, and lung cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans.12,24

Recently, a new acquired immune deficiency syndrome has been described in East Asia. In this syndrome, interferon–gamma (IFN–gamma) is blocked by an auto-antibody. Although not communicable like human immunodeficiency virus, this autoimmune syndrome may lead to similar opportunistic infections such as atypical mycobacterial infections.25

Mental health concerns

Perhaps no topic deserves more emphasis than that of mental health. In the aftermath of the war in Vietnam, Southeast Asian immigrants suffered a great deal from traumatic immigration experiences, with severe adjustment reactions.26 A high incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the Hmong in particular reflects their turbulent national history.27

While the incidence of mental illness among Asians is comparable to that of the general population, Asian Americans are less likely to report such problems or to use mental health services26 due to the stigmatization of mental illness in Asian culture.28 Consequently, these symptoms may be subconsciously converted into the more socially acceptable medium of physical illness, which “saves face” and preserves family honor.29 In many ways, Asian culture still perceives mental illness as personal weakness.30 In Hmong culture, inability to speak about being depressed stems not just from cultural bias but from linguistic constraints—the language simply lacks a word for depression.31 Even Asian cultures recognizing mental illness deem depression to be more dependent on circumstances than on the psyche.31 A first-generation immigrant with mental illness is therefore more likely to present with somatic symptoms than a mood disturbance, and is likely to be resistant to counseling or medication for depression. (See “Cultural influence on self-perception: A case ”).

Asian health care beliefs and illnesses

Asian culture substantially influences the ways in which an individual perceives disease, experiences illness, and copes with the phenomenon of sickness. The interplay between illness, disease, and sickness was first elucidated by the pioneering work of Arthur Kleinman, MD, in 1978.32 The term disease denotes a pathological process, while illness describes the subjective impact of disease in a patient’s life. Sickness is the sum of both, as it relates to the total picture of biological and social disruption. The culturally competent physician must understand not only the patient’s disease but also his experience of illness. Asking Dr. Kleinman’s questions will help physicians understand their patient’s perception of illness (TABLE 2).32

Traditional Chinese medicine

Many East Asians derive their conception of illness from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), a broad range of therapies including herbs, acupuncture, massage (tuina), and diet that has been used for millennia. Similarly, South Asians are influenced by the Ayurvedic or Unani traditions. TCM views the body as an energy system, rather than a machine, through which the life force, or chi, flows. Health is not just the absence of disease, but a proper balance of the antithetic forces, yin and yang, maintained by herbs, diet, and acupuncture.33 TCM is often preferred for treating chronic conditions and viral syndromes, or as a substitute for Western medications with adverse effects.34 It is most popular among newly arrived immigrants, those with low literacy, and those with limited access to conventional medical treatment.34 Most Western physicians know little about TCM, feel uncomfortable when their patients use it, and fail to recognize its popularity.34,35 Likewise, most Asian patients are reluctant to discuss their use of TCM unless questioned about it in a nonjudgmental manner.

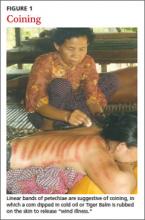

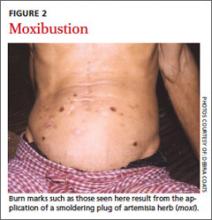

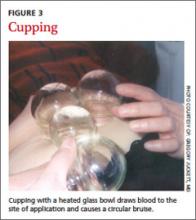

Many East Asian cultures practice a distinct form of folk healing known as “coining,” in which a coin dipped in cold oil or Tiger Balm is rubbed against the skin, enabling “wind illness” to escape the body (FIGURE 1). Linear bands of painless petechiae develop. The more extensive the bruising, the more illness is thought to be released. Failure to expel “wind-cold” from the body is believed to account for many ailments. Other traditions are moxibustion and cupping. In moxibustion, a smoldering plug of dried artemisia herb (moxi) is either impaled upon an acupuncture needle or placed directly on the skin to create a burn (FIGURE 2). In cupping, a flame is quickly passed through a glass bowl which is then placed against the skin. The resulting suction creates a circular bruise and draws blood to the area (FIGURE 3). Many folk remedies have been mistaken for child abuse by individuals unfamiliar with such practices.36 Occasionally TCM may result in harm from burns, unsterilized acupuncture needles, or (most commonly) adulterated herbal formulations.37

Culture-bound syndromes

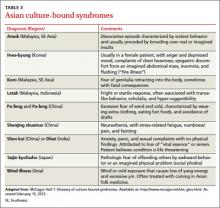

Asian folk illnesses usually go unrecognized by western practitioners, and many of these are somatic presentations of mental illness or stress (TABLE 3). A classic example is the Korean folk condition Hwa-byung, which may include the sensation of an abdominal mass. US practitioners might pursue a fruitless abdominal workup before suspecting a psychiatric condition, even though a careful history would likely elicit other anxiety symptoms and loss of sleep and appetite.26

Asian social conventions

Asian cultural conventions often create considerable confusion. In India, head waggling (shaking the head back and forth) is equivalent to nodding in conversation, indicating an acknowledgement of communication. To western eyes, it appears that the patient is resisting advice rather than welcoming it. In East Asians, smiling expresses a variety of emotions, including polite disagreement. Acute embarrassment may provoke giggling. Eye contact is usually for social equals; avoiding it, especially between the sexes, is the norm. Only the right hand should be used when giving patients a prescription; the left hand is considered unclean. A patient’s head should only be touched with advance permission, as it is viewed as the seat of the soul and is therefore sacred. Under no circumstances should a patient ever see the bottom of the practitioner’s feet or be touched by them.38 Demonstrating respect (especially for older Asians) and preserving modesty are essential when examining patients.

Naming conventions can also be confusing. In China and much of Southeast Asia, it is customary for the surname to precede the given name, often with the 2 run together, rather than the other way round. It is best to ask how a patient would prefer to be addressed, regardless of how the name appears on the medical chart.38

Cultivating knowledge of Asian culture provides a framework from which practitioners can better understand and treat their patients. By asking respectful, open ended questions and encouraging patients to take an active role in their own treatment, physicians become therapeutic allies actively engaged in the healing process. Asking patients to share their use of alternative remedies allows the option of rationally integrating those most meaningful for the patient.

The cross-cultural interview

It is helpful to have a specific approach in mind when interviewing patients from other cultures. A number of mnemonic techniques exist.39-41 Perhaps the most useful of these is the LEARN model, which stands for Listen, Explain, Acknowledge, Recommend, and Negotiate.39 The physician first listens carefully to the patient’s perception of his illness before explaining any medical (disease) issues. This exchange is followed by acknowledging differences and similarities between the 2 viewpoints. Finally, the physician recommends a treatment plan and negotiates patient agreement.39 Negotiation implies flexibility and willingness to compromise with reasonable cultural demands, without compromising patient care. Use of the LEARN model aids in the identification and resolution of any cultural conflicts that might arise during the course of the clinical interview.

Teach back and patient activation

An extremely useful technique for all cultures is termed “teach back” or “show me,” which involves asking patients to repeat their care instructions at the end of the visit. This extra step provides an opportunity to correct errors that might have occurred during the transmission of instructions.42 Caregivers should also encourage or “activate” patients to become more involved in managing their own health care. Patient activation measures may be assessed on a one-to-4 point scale.43 Using both of these techniques combats passivity, promotes patient acceptance, and improves outcomes.

A caring environment

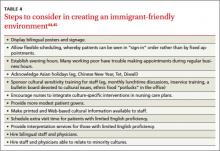

There are various strategies and approaches that can help make a medical practice more immigrant friendly (TABLE 4).44,45 Instructing office staff to assist patients in getting to the clinic is critical for those with limited mobility or who lack English proficiency. Adding evening hours that can also accommodate walk-ins helps working patients. For practices with larger immigrant populations, recognizing Asian holidays like Chinese New Year, Diwali, or Tet will be well received. These practices have been directly correlated with more positive health outcomes and better patient satisfaction.44

Conveying complex instructions to patients with little English takes effort for even the most unflappable providers. While written follow-up instructions in English could be interpreted by a more fluent family member, the ideal solution would be to have materials available in the native language. Fortunately, several Web sites, such as SPIRAL (Selective Patient Information in Asian Languages) provide downloadable Asian language instructions.46

Physicians should try to implement the Culturally & Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) guidelines and mandates from the Office of Minority Health (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15).6 They go far towards providing optimal care for patients of all cultures. Cultural competence does not imply being an expert in all cultures, let alone those of Asia. However, health care providers can develop the skills necessary for effective cross-cultural communication, which, to be most effective, must be accompanied by a caring attitude and respectful practice environment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gregory Juckett, MD, MPH, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Box 9247, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center, Morgantown, West Virginia, 26506; [email protected]

1. Min PG, ed. Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press; 2006.

2. Ortman JM, Guarneri CE; National Census Bureau. United States population projections: 2000 to 2050. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

3. Barnes JS, Bennett CE; US Census Bureau Web site. The Asian population: 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. Published February 2002. Accessed February 2, 2012.

4. Kim G, Worley CB, Allen RS, et al. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1246-1252.

5. Silver D, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Transportation to clinic: findings from a pilot clinic-based survey of low-income suburbanites. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:350-355.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health Web site. The National CLAS Standards. Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15. Updated May 3, 2013. Accessed June 1, 2013.

7. Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727-754.

8. Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, et al. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800-806.

9. Ku L, Flores G. Pay now or pay later: providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:435-444.

10. Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagali MP, Clarridge BR, et al. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:44-52.

11. Basabe N, Ros M. Cultural dimensions and social behavior correlates: individualism-collectivism and power distance. Revue Internationale De Pscyhologie Sociale. 2005;17:189-225.

12. Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans’ reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:111-119.

13. Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, et al; The Commonwealth Fund. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2002/Mar/Diverse-Communities--Common-Concerns--Assessing-Health-Care-Quality-for-Minority-Americans.aspx. Published March 2002. Accessed December 20, 2013.

14. Houston HR, Harada N, Makinodan T. Development of a culturally sensitive educational intervention program to reduce high incidence of tuberculosis among foreign-born Vietnamese. Ethn Health. 2002;7:255-265.

15. Mazurel GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-5):1-25.

16. Hutton DW, Tan D, So SK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening and vaccinating Asian and Pacific Islander adults for hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:460-469.

17. Fattovich G, Brollo L, Giustina G, et al. Natural history and prognostic factors in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 1991;32:294-298.

18. Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1942-1956.

19. Smith C. Managing Adult Patients with Chronic HBV. Hepatitis B Foundation. Accessed February 15, 2012, at http://www.hepb.org/professionals/management_guidelines.htm.

20. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022.

21. Hamaad A, Lip G. Assessing heart disease in your ethnic patients. Pulse. 2003;63:48-49.

22. Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation. 2006;113:e924-e929.

23. Venkataraman R, Nanda NC, Beweja G, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and related conditions in Asian Indians living in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:977-980.

24. Nishtar S. Prevention of coronary heart disease in south Asia. Lancet. 2002;360:1015-1018.

25. Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:725-734.

26. Sorkin DH, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q. Assessing the mental health needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian American older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:595-602.

27. PTSD, depression epidemic among Cambodian immigrants [press release]. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; August 2, 2005.

28. Sue S, Sue DW, Sue L, et al. Psychopathology among Asian Americans: a model minority? Cult Divers Ment Health. 1995;1:39-51.

29. Parker G, Cheah YC, Roy K. Do the Chinese somaticize depression? A cross-cultural study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:287-293.

30. Sribney W, Elliot K, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. The role of nonmedical human services and alternative medicine. In: Ruiz P, Primm A, eds. Disparities in Psychiatric Care. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2010:274-289.

31. Lee HY, Lytle K, Yang PN, et al. Mental health literacy in Hmong and Cambodian elderly refugees: a barrier to understanding, recognizing, and responding to depression. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2010;71:323-344.

32. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthroplologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

33. Patwardhan B, Warude D, Pushpangadan P, et al. Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:465-473.

34. Wu AP, Burke A, LeBaron S. Use of traditional medicine by immigrant Chinese patients. Fam Med. 2007;39:195-200.

35. Nguyen G, Bowman M. Culture, language, and health literacy: communicating about health with Asians and Pacific Islanders. Fam Med. 2007;39:208-210.

36. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:665-666.

37. Efferth T, Kaina B. Toxicities by herbal medicines with emphasis to traditional Chinese medicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:989-996.

38. Galanti G. Communication and time orientation. In: Caring for Patients from Different Cultures. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008:27-51.

39. Berlin E, Fowkes WC Jr. A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care: application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139:934-938.

40. Stuart MR, Lieberman JA III, eds. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. 2nd ed. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1993:101-183.

41. Kobylarz FA, Heath JM, Like RC. The ETHNIC(S) mnemonic: a clinical tool for ethnogeriatric education. J Am Geriat Soc. 2002;50:1582-1589.

42. Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:171-177.

43. Patient Activation Measure Assessment. Insignia Health Web site. Available at: http://www.insigniahealth.com/solutions/patientactivation-measure. Accessed February 20, 2012.

44. Glenn-Vega A. Achieving a more minority-friendly practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9:39-43.

45. Galanti G. Making a Difference. In: Caring for Patients from Different Cultures. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2003:1222-1229.

46. SPIRAL: Selected Patient Information in Asian Languages. Tufts University Hirsh Health Sciences Web site. Available at: http://spiral.tufts.edu/topic.shtml. Accessed February 10, 2012.

› Ask Asian immigrants open-ended questions and encourage them to share their use of alternative remedies. C

› Consider providing an interpretation service for patients not proficient in English, as opposed to asking family members to help. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Though often considered a “model minority,” Asian immigrants pose significant challenges for Western health care providers, including radically different ideas of disease causation, differing communication styles, and somatic presentations of mental illness. Asian diversity is tremendous, but several cultural trends are held in common: strong family structures, respect, adaptability, and, for first generation immigrants, widespread use of traditional therapies.1

While Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs) represent only 5.6% of the US population, or 17.3 million people, that figure represents a 46% increase between 2000 and 2010, the most rapid for any ethnic group.2 A 79% increase is anticipated by 2050, bringing Asians to 9.3% of the US population. In order of population, API subpopulations include Chinese, Filipinos, Asian Indians, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese.2 More than half of Asian Americans reside in the states of California, New York, and Hawaii, although enclaves exist in most major cities.3

Addressing the health needs of Asian immigrants in an increasingly diverse society mandates that US physicians develop the necessary skills to communicate, even when expectations for care may be very different. Fortunately, excellent resources are available (TABLE 1).

Barriers to good healthcare

The most formidable obstacle is limited English proficiency of patients, making them significantly less likely to seek care.4 They often struggle to arrange an appointment, although they arrive on time.5

Inadequate interpretation services. Frequently family members must interpret for patients, despite a federal mandate (Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) requiring professional services be provided at no charge if there is a federal payer (Medicare or Medicaid) involved.6 Unfortunately, these services are not currently reimbursable. Use of family or friends as interpreters, while convenient, results in far less accurate interpretation, frequent embarrassment, and loss of patient confidentiality. Trained medical interpreters or even telephone services are preferable, as they are much more accurate. Interviews involve a triad comprised of provider, patient, and interpreter, with the provider speaking directly to the patient using first-person address at all times. The interpreter should sit to the side or slightly behind the patient. All communication should be interpreted sentence by sentence so everyone is able to understand the entire conversation. It is well documented that proper interpretive services vastly improve the quality of care.7

Patient illiteracy. Health care illiteracy leads to medication errors due to the inability to understand instructions.8 Some immigrants have the added disadvantage of being illiterate both in English and in their native tongue.4 If not remedied, these situations easily lead to drug overdoses or missed allergies.9 Older immigrants neither understand the intricacies of the US health care system nor possess the language skills to master it.4

Stereotyping by caregivers must be surmounted if patients are to receive quality care. Many Asian patients report that physicians fail to understand them as unique individuals apart from their ethnic identity. Others feel excluded from the decision-making process or find culturally sensitive treatment options lacking.10

Subtleties of relational interaction. Asian culture has been defined as possessing a high Power Distance Index (PDI).11 The PDI refers to the distance or level of respect which an individual must afford to a superior, and this ideal is reflected in Asian conformance to a strict social hierarchy. Thus, physicians are viewed as authority figures and it is proper to nod or smile to indicate polite deference.12 However, showing respect and “buying in” to treatment recommendations are entirely different matters. Cultural factors make it difficult for patients to openly disagree with physician recommendations without feeling as though they have been disrespectful.12 Asian cultures are also “high context” cultures, having far more unwritten rules for conduct and communication that often prove baffling to westerners from “lower context” cultures.

Financial limitations. Socioeconomic influences also play a role. Although Asians have a higher income than other minority groups, 12.5% of Asians still live in poverty and 17.2% lack health insurance.2 Lack of coverage makes many Asians reluctant to seek regular medical care.13

Special medical concerns

Asian-Americans face a variety of challenging medical issues, including disproportionately high rates of tuberculosis (TB) and hepatitis B.

TB. Although rates of TB infection in the United States are low, rates in Asian immigrants are up to 100 times greater than that of the general population, more than any other immigrant group.14 Screening with interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs), such as T-SPOT TB, should be routine for Asian immigrants, since IGRAs do not cross-react with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends IGRA blood testing in lieu of tuberculin skin testing (TST) for immigrants who received BCG in infancy, with the exception of children <5 years, for whom the TST is still preferable.15 Patients with positive IGRA tests are also more likely to be amenable to treatment.

Chronic hepatitis B infection in Asian immigrants is often due to perinatal transmission in their home countries. Rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the United States have been steadily declining since vaccination began in 1981. However, chronic HBV infection in Asian immigrants approaches 10% of that population.16 An estimated 15% to 20% of patients with chronic HBV develop cirrhosis within 5 years and are at high risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).17,18

Evaluate HBV carriers annually with liver function testing (LFTs), hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis B e-Antigen (HBeAg). A positive HBsAg result indicates the virus is present; a positive HBeAg result indicates the virus is actively replicating. LFT elevation (AST >200 IU/L) or a positive HBeAg test should prompt referral to a gastroenterologist for liver biopsy and therapy. Screening for HCC with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and liver ultrasounds every 6 to 12 months has been recommended for all chronic HBV carriers,19 but this interval remains controversial. Screen men ≥40 years and women ≥50, or anyone who has had HBV infection >10 years, every 6 months.19,20 More recent recommendations favor ultrasound over AFP for screening, as the latter test lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity.20 Test partners and family members of HBV patients, and vaccinate them against HBV if not already immune.

Other medical issues. Asians from the Indian subcontinent have a significantly elevated risk of heart disease, in part due to low HDL-cholesterol levels.21 South Asian immigrant populations have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death compared with other ethnicities, and often exhibit coronary disease before the age of 40.22 The recent adoption of a Western diet and sedentary lifestyle has provoked an epidemic of diabetes throughout urban Asia and in Asians living abroad. This may be related to the “thrifty gene hypothesis,” which suggests that genes which evolved early in human history to facilitate storage of fat for periods of famine are detrimental in modern society where food is plentiful. A study of Asian Indian immigrants in Atlanta demonstrated an 18.3% prevalence rate for diabetes, higher than any other ethnic group.23 Tobacco and its causal relationship with lung cancer and heart disease only adds to this concern. Southeast Asians in particular demonstrate alarmingly high rates of tobacco consumption, and lung cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans.12,24

Recently, a new acquired immune deficiency syndrome has been described in East Asia. In this syndrome, interferon–gamma (IFN–gamma) is blocked by an auto-antibody. Although not communicable like human immunodeficiency virus, this autoimmune syndrome may lead to similar opportunistic infections such as atypical mycobacterial infections.25

Mental health concerns

Perhaps no topic deserves more emphasis than that of mental health. In the aftermath of the war in Vietnam, Southeast Asian immigrants suffered a great deal from traumatic immigration experiences, with severe adjustment reactions.26 A high incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the Hmong in particular reflects their turbulent national history.27

While the incidence of mental illness among Asians is comparable to that of the general population, Asian Americans are less likely to report such problems or to use mental health services26 due to the stigmatization of mental illness in Asian culture.28 Consequently, these symptoms may be subconsciously converted into the more socially acceptable medium of physical illness, which “saves face” and preserves family honor.29 In many ways, Asian culture still perceives mental illness as personal weakness.30 In Hmong culture, inability to speak about being depressed stems not just from cultural bias but from linguistic constraints—the language simply lacks a word for depression.31 Even Asian cultures recognizing mental illness deem depression to be more dependent on circumstances than on the psyche.31 A first-generation immigrant with mental illness is therefore more likely to present with somatic symptoms than a mood disturbance, and is likely to be resistant to counseling or medication for depression. (See “Cultural influence on self-perception: A case ”).

Asian health care beliefs and illnesses

Asian culture substantially influences the ways in which an individual perceives disease, experiences illness, and copes with the phenomenon of sickness. The interplay between illness, disease, and sickness was first elucidated by the pioneering work of Arthur Kleinman, MD, in 1978.32 The term disease denotes a pathological process, while illness describes the subjective impact of disease in a patient’s life. Sickness is the sum of both, as it relates to the total picture of biological and social disruption. The culturally competent physician must understand not only the patient’s disease but also his experience of illness. Asking Dr. Kleinman’s questions will help physicians understand their patient’s perception of illness (TABLE 2).32

Traditional Chinese medicine

Many East Asians derive their conception of illness from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), a broad range of therapies including herbs, acupuncture, massage (tuina), and diet that has been used for millennia. Similarly, South Asians are influenced by the Ayurvedic or Unani traditions. TCM views the body as an energy system, rather than a machine, through which the life force, or chi, flows. Health is not just the absence of disease, but a proper balance of the antithetic forces, yin and yang, maintained by herbs, diet, and acupuncture.33 TCM is often preferred for treating chronic conditions and viral syndromes, or as a substitute for Western medications with adverse effects.34 It is most popular among newly arrived immigrants, those with low literacy, and those with limited access to conventional medical treatment.34 Most Western physicians know little about TCM, feel uncomfortable when their patients use it, and fail to recognize its popularity.34,35 Likewise, most Asian patients are reluctant to discuss their use of TCM unless questioned about it in a nonjudgmental manner.

Many East Asian cultures practice a distinct form of folk healing known as “coining,” in which a coin dipped in cold oil or Tiger Balm is rubbed against the skin, enabling “wind illness” to escape the body (FIGURE 1). Linear bands of painless petechiae develop. The more extensive the bruising, the more illness is thought to be released. Failure to expel “wind-cold” from the body is believed to account for many ailments. Other traditions are moxibustion and cupping. In moxibustion, a smoldering plug of dried artemisia herb (moxi) is either impaled upon an acupuncture needle or placed directly on the skin to create a burn (FIGURE 2). In cupping, a flame is quickly passed through a glass bowl which is then placed against the skin. The resulting suction creates a circular bruise and draws blood to the area (FIGURE 3). Many folk remedies have been mistaken for child abuse by individuals unfamiliar with such practices.36 Occasionally TCM may result in harm from burns, unsterilized acupuncture needles, or (most commonly) adulterated herbal formulations.37

Culture-bound syndromes

Asian folk illnesses usually go unrecognized by western practitioners, and many of these are somatic presentations of mental illness or stress (TABLE 3). A classic example is the Korean folk condition Hwa-byung, which may include the sensation of an abdominal mass. US practitioners might pursue a fruitless abdominal workup before suspecting a psychiatric condition, even though a careful history would likely elicit other anxiety symptoms and loss of sleep and appetite.26

Asian social conventions

Asian cultural conventions often create considerable confusion. In India, head waggling (shaking the head back and forth) is equivalent to nodding in conversation, indicating an acknowledgement of communication. To western eyes, it appears that the patient is resisting advice rather than welcoming it. In East Asians, smiling expresses a variety of emotions, including polite disagreement. Acute embarrassment may provoke giggling. Eye contact is usually for social equals; avoiding it, especially between the sexes, is the norm. Only the right hand should be used when giving patients a prescription; the left hand is considered unclean. A patient’s head should only be touched with advance permission, as it is viewed as the seat of the soul and is therefore sacred. Under no circumstances should a patient ever see the bottom of the practitioner’s feet or be touched by them.38 Demonstrating respect (especially for older Asians) and preserving modesty are essential when examining patients.

Naming conventions can also be confusing. In China and much of Southeast Asia, it is customary for the surname to precede the given name, often with the 2 run together, rather than the other way round. It is best to ask how a patient would prefer to be addressed, regardless of how the name appears on the medical chart.38

Cultivating knowledge of Asian culture provides a framework from which practitioners can better understand and treat their patients. By asking respectful, open ended questions and encouraging patients to take an active role in their own treatment, physicians become therapeutic allies actively engaged in the healing process. Asking patients to share their use of alternative remedies allows the option of rationally integrating those most meaningful for the patient.

The cross-cultural interview

It is helpful to have a specific approach in mind when interviewing patients from other cultures. A number of mnemonic techniques exist.39-41 Perhaps the most useful of these is the LEARN model, which stands for Listen, Explain, Acknowledge, Recommend, and Negotiate.39 The physician first listens carefully to the patient’s perception of his illness before explaining any medical (disease) issues. This exchange is followed by acknowledging differences and similarities between the 2 viewpoints. Finally, the physician recommends a treatment plan and negotiates patient agreement.39 Negotiation implies flexibility and willingness to compromise with reasonable cultural demands, without compromising patient care. Use of the LEARN model aids in the identification and resolution of any cultural conflicts that might arise during the course of the clinical interview.

Teach back and patient activation

An extremely useful technique for all cultures is termed “teach back” or “show me,” which involves asking patients to repeat their care instructions at the end of the visit. This extra step provides an opportunity to correct errors that might have occurred during the transmission of instructions.42 Caregivers should also encourage or “activate” patients to become more involved in managing their own health care. Patient activation measures may be assessed on a one-to-4 point scale.43 Using both of these techniques combats passivity, promotes patient acceptance, and improves outcomes.

A caring environment

There are various strategies and approaches that can help make a medical practice more immigrant friendly (TABLE 4).44,45 Instructing office staff to assist patients in getting to the clinic is critical for those with limited mobility or who lack English proficiency. Adding evening hours that can also accommodate walk-ins helps working patients. For practices with larger immigrant populations, recognizing Asian holidays like Chinese New Year, Diwali, or Tet will be well received. These practices have been directly correlated with more positive health outcomes and better patient satisfaction.44

Conveying complex instructions to patients with little English takes effort for even the most unflappable providers. While written follow-up instructions in English could be interpreted by a more fluent family member, the ideal solution would be to have materials available in the native language. Fortunately, several Web sites, such as SPIRAL (Selective Patient Information in Asian Languages) provide downloadable Asian language instructions.46

Physicians should try to implement the Culturally & Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) guidelines and mandates from the Office of Minority Health (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15).6 They go far towards providing optimal care for patients of all cultures. Cultural competence does not imply being an expert in all cultures, let alone those of Asia. However, health care providers can develop the skills necessary for effective cross-cultural communication, which, to be most effective, must be accompanied by a caring attitude and respectful practice environment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gregory Juckett, MD, MPH, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Box 9247, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center, Morgantown, West Virginia, 26506; [email protected]

› Ask Asian immigrants open-ended questions and encourage them to share their use of alternative remedies. C

› Consider providing an interpretation service for patients not proficient in English, as opposed to asking family members to help. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Though often considered a “model minority,” Asian immigrants pose significant challenges for Western health care providers, including radically different ideas of disease causation, differing communication styles, and somatic presentations of mental illness. Asian diversity is tremendous, but several cultural trends are held in common: strong family structures, respect, adaptability, and, for first generation immigrants, widespread use of traditional therapies.1

While Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs) represent only 5.6% of the US population, or 17.3 million people, that figure represents a 46% increase between 2000 and 2010, the most rapid for any ethnic group.2 A 79% increase is anticipated by 2050, bringing Asians to 9.3% of the US population. In order of population, API subpopulations include Chinese, Filipinos, Asian Indians, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese.2 More than half of Asian Americans reside in the states of California, New York, and Hawaii, although enclaves exist in most major cities.3

Addressing the health needs of Asian immigrants in an increasingly diverse society mandates that US physicians develop the necessary skills to communicate, even when expectations for care may be very different. Fortunately, excellent resources are available (TABLE 1).

Barriers to good healthcare

The most formidable obstacle is limited English proficiency of patients, making them significantly less likely to seek care.4 They often struggle to arrange an appointment, although they arrive on time.5

Inadequate interpretation services. Frequently family members must interpret for patients, despite a federal mandate (Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) requiring professional services be provided at no charge if there is a federal payer (Medicare or Medicaid) involved.6 Unfortunately, these services are not currently reimbursable. Use of family or friends as interpreters, while convenient, results in far less accurate interpretation, frequent embarrassment, and loss of patient confidentiality. Trained medical interpreters or even telephone services are preferable, as they are much more accurate. Interviews involve a triad comprised of provider, patient, and interpreter, with the provider speaking directly to the patient using first-person address at all times. The interpreter should sit to the side or slightly behind the patient. All communication should be interpreted sentence by sentence so everyone is able to understand the entire conversation. It is well documented that proper interpretive services vastly improve the quality of care.7

Patient illiteracy. Health care illiteracy leads to medication errors due to the inability to understand instructions.8 Some immigrants have the added disadvantage of being illiterate both in English and in their native tongue.4 If not remedied, these situations easily lead to drug overdoses or missed allergies.9 Older immigrants neither understand the intricacies of the US health care system nor possess the language skills to master it.4

Stereotyping by caregivers must be surmounted if patients are to receive quality care. Many Asian patients report that physicians fail to understand them as unique individuals apart from their ethnic identity. Others feel excluded from the decision-making process or find culturally sensitive treatment options lacking.10

Subtleties of relational interaction. Asian culture has been defined as possessing a high Power Distance Index (PDI).11 The PDI refers to the distance or level of respect which an individual must afford to a superior, and this ideal is reflected in Asian conformance to a strict social hierarchy. Thus, physicians are viewed as authority figures and it is proper to nod or smile to indicate polite deference.12 However, showing respect and “buying in” to treatment recommendations are entirely different matters. Cultural factors make it difficult for patients to openly disagree with physician recommendations without feeling as though they have been disrespectful.12 Asian cultures are also “high context” cultures, having far more unwritten rules for conduct and communication that often prove baffling to westerners from “lower context” cultures.

Financial limitations. Socioeconomic influences also play a role. Although Asians have a higher income than other minority groups, 12.5% of Asians still live in poverty and 17.2% lack health insurance.2 Lack of coverage makes many Asians reluctant to seek regular medical care.13

Special medical concerns

Asian-Americans face a variety of challenging medical issues, including disproportionately high rates of tuberculosis (TB) and hepatitis B.

TB. Although rates of TB infection in the United States are low, rates in Asian immigrants are up to 100 times greater than that of the general population, more than any other immigrant group.14 Screening with interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs), such as T-SPOT TB, should be routine for Asian immigrants, since IGRAs do not cross-react with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends IGRA blood testing in lieu of tuberculin skin testing (TST) for immigrants who received BCG in infancy, with the exception of children <5 years, for whom the TST is still preferable.15 Patients with positive IGRA tests are also more likely to be amenable to treatment.

Chronic hepatitis B infection in Asian immigrants is often due to perinatal transmission in their home countries. Rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the United States have been steadily declining since vaccination began in 1981. However, chronic HBV infection in Asian immigrants approaches 10% of that population.16 An estimated 15% to 20% of patients with chronic HBV develop cirrhosis within 5 years and are at high risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).17,18

Evaluate HBV carriers annually with liver function testing (LFTs), hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis B e-Antigen (HBeAg). A positive HBsAg result indicates the virus is present; a positive HBeAg result indicates the virus is actively replicating. LFT elevation (AST >200 IU/L) or a positive HBeAg test should prompt referral to a gastroenterologist for liver biopsy and therapy. Screening for HCC with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and liver ultrasounds every 6 to 12 months has been recommended for all chronic HBV carriers,19 but this interval remains controversial. Screen men ≥40 years and women ≥50, or anyone who has had HBV infection >10 years, every 6 months.19,20 More recent recommendations favor ultrasound over AFP for screening, as the latter test lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity.20 Test partners and family members of HBV patients, and vaccinate them against HBV if not already immune.

Other medical issues. Asians from the Indian subcontinent have a significantly elevated risk of heart disease, in part due to low HDL-cholesterol levels.21 South Asian immigrant populations have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death compared with other ethnicities, and often exhibit coronary disease before the age of 40.22 The recent adoption of a Western diet and sedentary lifestyle has provoked an epidemic of diabetes throughout urban Asia and in Asians living abroad. This may be related to the “thrifty gene hypothesis,” which suggests that genes which evolved early in human history to facilitate storage of fat for periods of famine are detrimental in modern society where food is plentiful. A study of Asian Indian immigrants in Atlanta demonstrated an 18.3% prevalence rate for diabetes, higher than any other ethnic group.23 Tobacco and its causal relationship with lung cancer and heart disease only adds to this concern. Southeast Asians in particular demonstrate alarmingly high rates of tobacco consumption, and lung cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans.12,24

Recently, a new acquired immune deficiency syndrome has been described in East Asia. In this syndrome, interferon–gamma (IFN–gamma) is blocked by an auto-antibody. Although not communicable like human immunodeficiency virus, this autoimmune syndrome may lead to similar opportunistic infections such as atypical mycobacterial infections.25

Mental health concerns

Perhaps no topic deserves more emphasis than that of mental health. In the aftermath of the war in Vietnam, Southeast Asian immigrants suffered a great deal from traumatic immigration experiences, with severe adjustment reactions.26 A high incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the Hmong in particular reflects their turbulent national history.27

While the incidence of mental illness among Asians is comparable to that of the general population, Asian Americans are less likely to report such problems or to use mental health services26 due to the stigmatization of mental illness in Asian culture.28 Consequently, these symptoms may be subconsciously converted into the more socially acceptable medium of physical illness, which “saves face” and preserves family honor.29 In many ways, Asian culture still perceives mental illness as personal weakness.30 In Hmong culture, inability to speak about being depressed stems not just from cultural bias but from linguistic constraints—the language simply lacks a word for depression.31 Even Asian cultures recognizing mental illness deem depression to be more dependent on circumstances than on the psyche.31 A first-generation immigrant with mental illness is therefore more likely to present with somatic symptoms than a mood disturbance, and is likely to be resistant to counseling or medication for depression. (See “Cultural influence on self-perception: A case ”).

Asian health care beliefs and illnesses

Asian culture substantially influences the ways in which an individual perceives disease, experiences illness, and copes with the phenomenon of sickness. The interplay between illness, disease, and sickness was first elucidated by the pioneering work of Arthur Kleinman, MD, in 1978.32 The term disease denotes a pathological process, while illness describes the subjective impact of disease in a patient’s life. Sickness is the sum of both, as it relates to the total picture of biological and social disruption. The culturally competent physician must understand not only the patient’s disease but also his experience of illness. Asking Dr. Kleinman’s questions will help physicians understand their patient’s perception of illness (TABLE 2).32

Traditional Chinese medicine

Many East Asians derive their conception of illness from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), a broad range of therapies including herbs, acupuncture, massage (tuina), and diet that has been used for millennia. Similarly, South Asians are influenced by the Ayurvedic or Unani traditions. TCM views the body as an energy system, rather than a machine, through which the life force, or chi, flows. Health is not just the absence of disease, but a proper balance of the antithetic forces, yin and yang, maintained by herbs, diet, and acupuncture.33 TCM is often preferred for treating chronic conditions and viral syndromes, or as a substitute for Western medications with adverse effects.34 It is most popular among newly arrived immigrants, those with low literacy, and those with limited access to conventional medical treatment.34 Most Western physicians know little about TCM, feel uncomfortable when their patients use it, and fail to recognize its popularity.34,35 Likewise, most Asian patients are reluctant to discuss their use of TCM unless questioned about it in a nonjudgmental manner.

Many East Asian cultures practice a distinct form of folk healing known as “coining,” in which a coin dipped in cold oil or Tiger Balm is rubbed against the skin, enabling “wind illness” to escape the body (FIGURE 1). Linear bands of painless petechiae develop. The more extensive the bruising, the more illness is thought to be released. Failure to expel “wind-cold” from the body is believed to account for many ailments. Other traditions are moxibustion and cupping. In moxibustion, a smoldering plug of dried artemisia herb (moxi) is either impaled upon an acupuncture needle or placed directly on the skin to create a burn (FIGURE 2). In cupping, a flame is quickly passed through a glass bowl which is then placed against the skin. The resulting suction creates a circular bruise and draws blood to the area (FIGURE 3). Many folk remedies have been mistaken for child abuse by individuals unfamiliar with such practices.36 Occasionally TCM may result in harm from burns, unsterilized acupuncture needles, or (most commonly) adulterated herbal formulations.37

Culture-bound syndromes

Asian folk illnesses usually go unrecognized by western practitioners, and many of these are somatic presentations of mental illness or stress (TABLE 3). A classic example is the Korean folk condition Hwa-byung, which may include the sensation of an abdominal mass. US practitioners might pursue a fruitless abdominal workup before suspecting a psychiatric condition, even though a careful history would likely elicit other anxiety symptoms and loss of sleep and appetite.26

Asian social conventions

Asian cultural conventions often create considerable confusion. In India, head waggling (shaking the head back and forth) is equivalent to nodding in conversation, indicating an acknowledgement of communication. To western eyes, it appears that the patient is resisting advice rather than welcoming it. In East Asians, smiling expresses a variety of emotions, including polite disagreement. Acute embarrassment may provoke giggling. Eye contact is usually for social equals; avoiding it, especially between the sexes, is the norm. Only the right hand should be used when giving patients a prescription; the left hand is considered unclean. A patient’s head should only be touched with advance permission, as it is viewed as the seat of the soul and is therefore sacred. Under no circumstances should a patient ever see the bottom of the practitioner’s feet or be touched by them.38 Demonstrating respect (especially for older Asians) and preserving modesty are essential when examining patients.

Naming conventions can also be confusing. In China and much of Southeast Asia, it is customary for the surname to precede the given name, often with the 2 run together, rather than the other way round. It is best to ask how a patient would prefer to be addressed, regardless of how the name appears on the medical chart.38

Cultivating knowledge of Asian culture provides a framework from which practitioners can better understand and treat their patients. By asking respectful, open ended questions and encouraging patients to take an active role in their own treatment, physicians become therapeutic allies actively engaged in the healing process. Asking patients to share their use of alternative remedies allows the option of rationally integrating those most meaningful for the patient.

The cross-cultural interview

It is helpful to have a specific approach in mind when interviewing patients from other cultures. A number of mnemonic techniques exist.39-41 Perhaps the most useful of these is the LEARN model, which stands for Listen, Explain, Acknowledge, Recommend, and Negotiate.39 The physician first listens carefully to the patient’s perception of his illness before explaining any medical (disease) issues. This exchange is followed by acknowledging differences and similarities between the 2 viewpoints. Finally, the physician recommends a treatment plan and negotiates patient agreement.39 Negotiation implies flexibility and willingness to compromise with reasonable cultural demands, without compromising patient care. Use of the LEARN model aids in the identification and resolution of any cultural conflicts that might arise during the course of the clinical interview.

Teach back and patient activation

An extremely useful technique for all cultures is termed “teach back” or “show me,” which involves asking patients to repeat their care instructions at the end of the visit. This extra step provides an opportunity to correct errors that might have occurred during the transmission of instructions.42 Caregivers should also encourage or “activate” patients to become more involved in managing their own health care. Patient activation measures may be assessed on a one-to-4 point scale.43 Using both of these techniques combats passivity, promotes patient acceptance, and improves outcomes.

A caring environment

There are various strategies and approaches that can help make a medical practice more immigrant friendly (TABLE 4).44,45 Instructing office staff to assist patients in getting to the clinic is critical for those with limited mobility or who lack English proficiency. Adding evening hours that can also accommodate walk-ins helps working patients. For practices with larger immigrant populations, recognizing Asian holidays like Chinese New Year, Diwali, or Tet will be well received. These practices have been directly correlated with more positive health outcomes and better patient satisfaction.44

Conveying complex instructions to patients with little English takes effort for even the most unflappable providers. While written follow-up instructions in English could be interpreted by a more fluent family member, the ideal solution would be to have materials available in the native language. Fortunately, several Web sites, such as SPIRAL (Selective Patient Information in Asian Languages) provide downloadable Asian language instructions.46

Physicians should try to implement the Culturally & Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) guidelines and mandates from the Office of Minority Health (http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15).6 They go far towards providing optimal care for patients of all cultures. Cultural competence does not imply being an expert in all cultures, let alone those of Asia. However, health care providers can develop the skills necessary for effective cross-cultural communication, which, to be most effective, must be accompanied by a caring attitude and respectful practice environment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gregory Juckett, MD, MPH, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Box 9247, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center, Morgantown, West Virginia, 26506; [email protected]

1. Min PG, ed. Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press; 2006.

2. Ortman JM, Guarneri CE; National Census Bureau. United States population projections: 2000 to 2050. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

3. Barnes JS, Bennett CE; US Census Bureau Web site. The Asian population: 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. Published February 2002. Accessed February 2, 2012.

4. Kim G, Worley CB, Allen RS, et al. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1246-1252.

5. Silver D, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Transportation to clinic: findings from a pilot clinic-based survey of low-income suburbanites. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:350-355.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health Web site. The National CLAS Standards. Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15. Updated May 3, 2013. Accessed June 1, 2013.

7. Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727-754.

8. Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, et al. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800-806.

9. Ku L, Flores G. Pay now or pay later: providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:435-444.

10. Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagali MP, Clarridge BR, et al. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:44-52.

11. Basabe N, Ros M. Cultural dimensions and social behavior correlates: individualism-collectivism and power distance. Revue Internationale De Pscyhologie Sociale. 2005;17:189-225.

12. Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans’ reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:111-119.

13. Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, et al; The Commonwealth Fund. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2002/Mar/Diverse-Communities--Common-Concerns--Assessing-Health-Care-Quality-for-Minority-Americans.aspx. Published March 2002. Accessed December 20, 2013.

14. Houston HR, Harada N, Makinodan T. Development of a culturally sensitive educational intervention program to reduce high incidence of tuberculosis among foreign-born Vietnamese. Ethn Health. 2002;7:255-265.

15. Mazurel GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-5):1-25.

16. Hutton DW, Tan D, So SK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening and vaccinating Asian and Pacific Islander adults for hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:460-469.

17. Fattovich G, Brollo L, Giustina G, et al. Natural history and prognostic factors in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 1991;32:294-298.

18. Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1942-1956.

19. Smith C. Managing Adult Patients with Chronic HBV. Hepatitis B Foundation. Accessed February 15, 2012, at http://www.hepb.org/professionals/management_guidelines.htm.

20. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022.

21. Hamaad A, Lip G. Assessing heart disease in your ethnic patients. Pulse. 2003;63:48-49.

22. Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation. 2006;113:e924-e929.

23. Venkataraman R, Nanda NC, Beweja G, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and related conditions in Asian Indians living in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:977-980.

24. Nishtar S. Prevention of coronary heart disease in south Asia. Lancet. 2002;360:1015-1018.

25. Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:725-734.

26. Sorkin DH, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q. Assessing the mental health needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian American older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:595-602.

27. PTSD, depression epidemic among Cambodian immigrants [press release]. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; August 2, 2005.

28. Sue S, Sue DW, Sue L, et al. Psychopathology among Asian Americans: a model minority? Cult Divers Ment Health. 1995;1:39-51.

29. Parker G, Cheah YC, Roy K. Do the Chinese somaticize depression? A cross-cultural study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:287-293.

30. Sribney W, Elliot K, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. The role of nonmedical human services and alternative medicine. In: Ruiz P, Primm A, eds. Disparities in Psychiatric Care. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2010:274-289.

31. Lee HY, Lytle K, Yang PN, et al. Mental health literacy in Hmong and Cambodian elderly refugees: a barrier to understanding, recognizing, and responding to depression. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2010;71:323-344.

32. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthroplologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

33. Patwardhan B, Warude D, Pushpangadan P, et al. Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:465-473.

34. Wu AP, Burke A, LeBaron S. Use of traditional medicine by immigrant Chinese patients. Fam Med. 2007;39:195-200.

35. Nguyen G, Bowman M. Culture, language, and health literacy: communicating about health with Asians and Pacific Islanders. Fam Med. 2007;39:208-210.

36. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:665-666.

37. Efferth T, Kaina B. Toxicities by herbal medicines with emphasis to traditional Chinese medicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:989-996.

38. Galanti G. Communication and time orientation. In: Caring for Patients from Different Cultures. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008:27-51.

39. Berlin E, Fowkes WC Jr. A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care: application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139:934-938.

40. Stuart MR, Lieberman JA III, eds. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. 2nd ed. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1993:101-183.

41. Kobylarz FA, Heath JM, Like RC. The ETHNIC(S) mnemonic: a clinical tool for ethnogeriatric education. J Am Geriat Soc. 2002;50:1582-1589.

42. Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:171-177.

43. Patient Activation Measure Assessment. Insignia Health Web site. Available at: http://www.insigniahealth.com/solutions/patientactivation-measure. Accessed February 20, 2012.

44. Glenn-Vega A. Achieving a more minority-friendly practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9:39-43.

45. Galanti G. Making a Difference. In: Caring for Patients from Different Cultures. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2003:1222-1229.

46. SPIRAL: Selected Patient Information in Asian Languages. Tufts University Hirsh Health Sciences Web site. Available at: http://spiral.tufts.edu/topic.shtml. Accessed February 10, 2012.

1. Min PG, ed. Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press; 2006.

2. Ortman JM, Guarneri CE; National Census Bureau. United States population projections: 2000 to 2050. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/files/analytical-document09.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2012.

3. Barnes JS, Bennett CE; US Census Bureau Web site. The Asian population: 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. Published February 2002. Accessed February 2, 2012.

4. Kim G, Worley CB, Allen RS, et al. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1246-1252.

5. Silver D, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. Transportation to clinic: findings from a pilot clinic-based survey of low-income suburbanites. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:350-355.

6. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health Web site. The National CLAS Standards. Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=15. Updated May 3, 2013. Accessed June 1, 2013.

7. Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727-754.

8. Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, et al. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800-806.

9. Ku L, Flores G. Pay now or pay later: providing interpreter services in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:435-444.

10. Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagali MP, Clarridge BR, et al. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:44-52.

11. Basabe N, Ros M. Cultural dimensions and social behavior correlates: individualism-collectivism and power distance. Revue Internationale De Pscyhologie Sociale. 2005;17:189-225.

12. Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans’ reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:111-119.

13. Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, et al; The Commonwealth Fund. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2002/Mar/Diverse-Communities--Common-Concerns--Assessing-Health-Care-Quality-for-Minority-Americans.aspx. Published March 2002. Accessed December 20, 2013.

14. Houston HR, Harada N, Makinodan T. Development of a culturally sensitive educational intervention program to reduce high incidence of tuberculosis among foreign-born Vietnamese. Ethn Health. 2002;7:255-265.

15. Mazurel GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using interferon Gamma Release Assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-5):1-25.

16. Hutton DW, Tan D, So SK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening and vaccinating Asian and Pacific Islander adults for hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:460-469.

17. Fattovich G, Brollo L, Giustina G, et al. Natural history and prognostic factors in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 1991;32:294-298.

18. Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1942-1956.

19. Smith C. Managing Adult Patients with Chronic HBV. Hepatitis B Foundation. Accessed February 15, 2012, at http://www.hepb.org/professionals/management_guidelines.htm.

20. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022.

21. Hamaad A, Lip G. Assessing heart disease in your ethnic patients. Pulse. 2003;63:48-49.

22. Gupta M, Singh N, Verma S. South Asians and cardiovascular risk: what clinicians should know. Circulation. 2006;113:e924-e929.

23. Venkataraman R, Nanda NC, Beweja G, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and related conditions in Asian Indians living in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:977-980.

24. Nishtar S. Prevention of coronary heart disease in south Asia. Lancet. 2002;360:1015-1018.

25. Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Adult onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:725-734.

26. Sorkin DH, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q. Assessing the mental health needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian American older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:595-602.

27. PTSD, depression epidemic among Cambodian immigrants [press release]. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; August 2, 2005.

28. Sue S, Sue DW, Sue L, et al. Psychopathology among Asian Americans: a model minority? Cult Divers Ment Health. 1995;1:39-51.

29. Parker G, Cheah YC, Roy K. Do the Chinese somaticize depression? A cross-cultural study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:287-293.

30. Sribney W, Elliot K, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. The role of nonmedical human services and alternative medicine. In: Ruiz P, Primm A, eds. Disparities in Psychiatric Care. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2010:274-289.

31. Lee HY, Lytle K, Yang PN, et al. Mental health literacy in Hmong and Cambodian elderly refugees: a barrier to understanding, recognizing, and responding to depression. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2010;71:323-344.

32. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthroplologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

33. Patwardhan B, Warude D, Pushpangadan P, et al. Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:465-473.

34. Wu AP, Burke A, LeBaron S. Use of traditional medicine by immigrant Chinese patients. Fam Med. 2007;39:195-200.

35. Nguyen G, Bowman M. Culture, language, and health literacy: communicating about health with Asians and Pacific Islanders. Fam Med. 2007;39:208-210.

36. Oates RK. Overturning the diagnosis of child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:665-666.

37. Efferth T, Kaina B. Toxicities by herbal medicines with emphasis to traditional Chinese medicine. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:989-996.

38. Galanti G. Communication and time orientation. In: Caring for Patients from Different Cultures. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2008:27-51.

39. Berlin E, Fowkes WC Jr. A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care: application in family practice. West J Med. 1983;139:934-938.

40. Stuart MR, Lieberman JA III, eds. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. 2nd ed. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1993:101-183.

41. Kobylarz FA, Heath JM, Like RC. The ETHNIC(S) mnemonic: a clinical tool for ethnogeriatric education. J Am Geriat Soc. 2002;50:1582-1589.

42. Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:171-177.