User login

Akathisia—from the Greek for “inability to sit”—is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by subjective and objective psychomotor restlessness. Patients typically experience feelings of unease, inner restlessness mainly involving the legs, and a compulsion to move. Most engage in repetitive movement. They might swing or cross and uncross their legs, shift from one foot to the other, continuously pace, or persistently fidget.

In clinical settings, akathisia usually is a side effect of medication. Antipsychotics, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and buspirone are common triggers, but akathisia also has been associated with some antiemetics, preoperative sedatives, calcium channel blockers, and antivertigo agents. It also can be caused by withdrawal from an antipsychotic or related to a substance use disorder, especially cocaine. Akathisia can be acute or chronic, occurring in a tardive form with symptoms that last >6 months.1-3

Much isn’t known about drug-induced akathisia

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of akathisia is incomplete. Some have suggested that it results from an imbalance between the dopaminergic/cholinergic and dopaminergic/serotonergic systems4; others, that the cause is a mismatch between the core and the shell of the nucleus accumbens, due in part to overstimulation of the locus ceruleus.5

More recently, researchers established a positive association between higher scores on the Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale and D2/D3 receptor occupancy in the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle).6 The D2/D3 receptor occupancy model might explain withdrawal symptoms associated with cocaine,7 as well as relative worsening of symptoms after tapering or discontinuing stimulants in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Elements of a clinical evaluation

When akathisia is suspected, evaluation by a clinician familiar with its phenomenology is crucial. A validated tool, such as the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (at out cometracker.org/library/BAS.pdf) can aid in the detection and assessment of severity.8

In evaluating patients, keep in mind that the inner restlessness that characterizes akathisia can affect the trunk, hands, and arms, as well as the legs, and can cause dysphoria and anxiety. Akathisia has been linked to an increased likelihood of developing suicidal ideation and behavior.9

Less common subjective symptoms include rage, fear, nausea, and worsening of psychotic symptoms. Because of its association with aggression and agitation, drug-induced akathisia has been cited—with little success—as the basis for an insanity defense by people who have committed a violent act.10

Or is akathisia another psychiatric disorder?

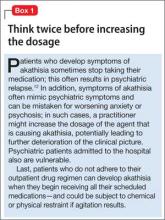

Akathisia might go undetected for several reasons. One key factor: Its symptoms resemble and often overlap with those of other psychiatric disorders, such as mania, psychosis, agitated depression, and ADHD. In addition, akathisia often occurs concurrently with, and is masked by, akinesia, a common extrapyramidal side effect of many antipsychotics. Such patients might have the inner feeling of restlessness and urge to move but do not exhibit characteristic limb movements. In some cases, cognitive or intellectual limitations prevent patients from communicating the inner turmoil they feel.11

Medication nonadherence further complicates the picture, sometimes prompting a clinician to increase the dosage of the drug that is causing akathisia (Box 112).

Managing drug-induced akathisia

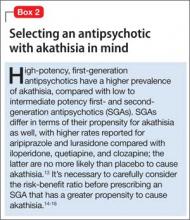

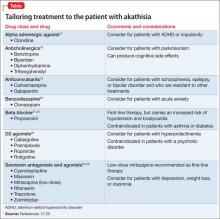

Akathisia usually resolves when the drug causing it is discontinued; decreasing the dosage might alleviate the symptoms. Whenever akathisia is detected, careful revision of the current drug regimen— substituting an antipsychotic with a lower prevalence of akathisia, for example— should be considered (Box 213-16). Treatment of drug-induced akathisia, which should be tailored to the patient’s psychopathology and comorbidities, is needed as well (Table17-25).

Beta blockers, particularly propranolol, are considered first-line therapy for drug-induced akathisia, with a dosage of 20 to 40 mg twice daily used to relieve symptoms26 The effect can be explained by adrenergic terminals in the locus ceruleus and ending in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex stimulate β adrenoreceptors.5,27 Although multiple small studies and case reports26,28-32 support the use of beta blockers to treat drug-induced akathisia, the quality of evidence of their efficacy is controversial.12,21,27 Consider the risk of hypotension and bradycardia and be aware of contraindications for patients with asthma or diabetes.

Low-dose mirtazapine (15 mg/d) was found to be as effective as propranolol, 80 mg/d, in a placebo-controlled study, and to be more effective than a beta blocker in treating akathisia induced by a first-generation antipsychotic. The authors concluded that both propranolol and mirtazapine should be first-line therapy.23 Others have suggested that these results be interpreted with caution because mirtazapine (at a higher dosage) has been linked to akathisia.33 Mirtazapine blocks α-adrenergic receptors, resulting in antagonism of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors and consequent enhancement of 5-HT1A serotonergic transmission.34 In one study, it was shown to reduce binding of the D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole.35

Serotonin antagonists and agonists. Blockade of 5-HT2 receptors can attenuate D2 blockade and mitigate akathisia symptoms. Mianserin, 15 mg/d, can be helpful, and ritanserin, 5 to 20 mg/d, produced about a 50% reduction in akathisia symptoms in 10 patients taking neuroleptics.36 Neither is available in the United States, however.

Cyproheptadine, a potent 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C antagonist with anticholinergic and antihistaminic action, improved akathisia symptoms in an open trial of 17 patients with antipsychotic-induced akathisia.37 The recommended dose is 8 to 16 mg/d.

A study using the selective inverse agonist pimavanserin (not FDA-approved) decreased akathisia in healthy volunteers taking haloperidol.14,24,33

Zolmitriptan, a 5-HT1D agonist, also can be used38; one study found that 7.5 mg/d of zolmitriptan is as effective as propranolol.39

A 2010 study showed a statistically significant improvement in 8 patients taking trazodone, compared with 5 patients on placebo, all of whom met criteria for at least mild akathisia. Trazodone’s antiakathitic effect is attributed to its 5-HT2A antagonism.25

Anticholinergics. Traditionally, benztropine, biperiden, diphenhydramine, and trihexyphenidyl have been used for prevention and treatment of extrapyramidal side effects. A Cochrane review concluded, however, that data are insufficient to support use of anticholinergics for akathisia.40 Although multiple case reports have shown anticholinergics to be effective in treating drug-induced akathisia,12,17,33 their association with cognitive side effects suggests a need for caution.18

Benzodiazepines. Through their sedative and anxiolytic properties, benzodiazepines are thought to partially alleviate akathisia symptoms. Two small trials found clonazepam helpful for akathisia symptoms2,20; and 1 case report revealed that a patient with akathisia improved after coadministration of clonazepam and baclofen.41

Anticonvulsants. Valproic acid has not been found to be useful in antipsychotic-induced tardive akathisia.42 However, a case report described a patient with schizophrenia whose akathisia symptoms improved after the dosage of gabapentin was increased.43 Last, carbamazepine was found to be effective in reducing akathisia symptoms in 3 patients with schizophrenia who were resistant to beta blockers, anticholinergics, antihistaminergics, and benzodiazepines.19

α-adrenergic agonists. In an open trial, akathisia symptoms in 6 patients improved with clonidine, 0.2 to 0.8 mg/d.17 Speculation is that strong α1 antagonism might help prevent akathisia, which could be why this condition is not associated with iloperidone.44

D2 agonists. Akathisia and restless legs syndrome have similar pathophysiology,1,2 and patients with akathisia could benefit from D2 agonists such as cabergoline, pramipexole, rotigotine, and ropinirole. One case study revealed that a patient with aripiprazole-induced akathisia improved with ropinirole.45 D2 agonists can precipitate or worsen psychosis, however, and would be a relative contraindication in patients with psychotic disorders.22

Bottom Line

Failure to detect drug-induced akathisia can increase morbidity and delay recovery in patients undergoing psychiatric care. Knowing what to look for and how to tailor treatment to the needs of a given patient is an essential component of good care.

Related Resources

• Ferrando SJ, Eisendrath SJ. Adverse neuropsychiatric effects of dopamine antagonist medications. Misdiagnosis in the medical setting. Psychosomatics. 1991;32(4):426-432.

• Vinson DR. Diphenhydramine in the treatment of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):265-270.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Haloperidol • Haldol

Baclofen • Lioresal Iloperidone • Fanapt

Benztropine • Cogentin Lurasidone • Latuda

Biperiden • Akineton Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buspirone • BuSpar Pramipexole • Mirapex

Cabergoline • Dostinex Propranolol • Inderal

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Ropinirole • Requip

Clonidine • Catapres Rotigotine • Neupro

Clozapine • Clozaril Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Cyproheptadine • Periactin Trihexyphenidyl • Artane

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Valproic acid • Depakene

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zolmitriptan • Zomig

Acknowledgement

Mandy Evans, MD, assisted with editing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosure

Dr. Forcen reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sachdev P. Akathisia and restless legs. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

2. Sachdev P, Longragan C. The present status of akathisia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(7):381-391.

3. Poyurovsky M, Hermesh H, Weizman A. Severe withdrawal akathisia following neuroleptic discontinuation successfully controlled by clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(4):283-286.

4. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Serotonin-based pharma-cotherapy for acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a new approach to an old problem. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:4-8.

5. Loonen AJ, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(1):7-10.

6. Kim JH, Son YD, Kim HK, et al. Antipsychotic-associated mental side effects and their relationship to dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in striatal subdivisions: a high-resolution PET study with [11C]raclopride. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):507-511.

7. Dailey JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptor predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315(5816):1267-1270.

8. Barnes TR, Braude WM. Akathisia variants and tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(9):874-878.

9. Seemüller F, Schennach R, Mayr A, et al. Akathisia and suicidal ideation in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(5):694-698.

10. Leong GB, Silva JA. Neuroleptic-induced akathisia and violence: a review. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(1):187-189.

11. Hirose S. The causes of underdiagnosing akathisia. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(3):547-558.

12. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):S1-S46; quiz 47-48.

13. Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879-911.

14. Poyurovsky M. Acute antipsychotic-induced akathisia revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):89-91.

15. Saltz BL, Robinson DG, Woerner MG. Recognizing and managing antipsychotic drug treatment side effects in the elderly. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(suppl 2):14-19.

16. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS. The NIMH-CATIE Schizophrenia Study: what did we learn? Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):770-775.

17. Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, Lipinski JF Jr, et al. Use of clonidine in treating neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatry Res. 1984;13(3):253-259.

18. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1055-1062.

19. Masui T, Kusumi I, Takahashi Y, et al. Efficacy of carbamazepine against neuroleptic-induced akathisia in treatment with perospirone: case series. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):343-346.

20. Lima AR, Soares-Weiser K, Bacaltchuk J, et al. Benzodiazepines for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001950.

21. Lima AR, Bacalcthuk J, Barnes TR, et al. Central action beta-blockers versus placebo for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD001946.

22. Bilal L, Ching C. Cabergoline-induced psychosis in a patient with undiagnosed depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E54.

23. Poyurovsky M, Pashinian A, Weizman A, et al. Low-dose mirtazapine: a new option in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propranolol-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry.

2006;59(11):1071-1077.

24. Maidment I. Use of serotonin antagonists in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2000;24(9):348-351.

25. Stryjer R, Rosenzcwaig S, Bar F, et al. Trazodone for the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(5):219-222.

26. Dumon JP, Catteau J, Lanvin F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled comparison of propranolol and betaxolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):647-650.

27. van Waarde A, Vaalburg W, Doze P, et al. PET imaging of beta-adrenoceptors in the human brain: a realistic goal or a mirage? Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(13):1519-1536.

28. Kurzthaler I, Hummer M, Kohl C, et al. Propranolol treatment of olanzapine-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1316.

29. Adler LA, Peselow E, Rosenthal MA, et al. A controlled comparison of the effects of propranolol, benztropine, and placebo on akathisia: an interim analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):283-286.

30. Dorevitch A, Durst R, Ginath Y. Propranolol in the treatment of akathisia caused by antipsychotic drugs. South Med J. 1991;84(12):1505-1506.

31. Lipinski JF Jr, Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, et al. Propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):412-415.

32. Adler L, Angrist B, Peselow E, et al. A controlled assessment of propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:42-45.

33. Kumar R, Sachdev PS. Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(3):293-299.

34. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(3):249-264.

35. Rogóz Z, Wróbel A, Dlaboga D, et al. Effect of repeated treatment with mirtazapine on the central dopaminergic D2/D3 receptors. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54(4):381-389.

36. Miller CH, Fleischhacker WW, Ehrmann H, et al. Treatment of neuroleptic induced akathisia with the 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26(3):373-376.

37. Weiss D, Aizenberg D, Hermesh H, et al. Cyproheptadine treatment in neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(4):483-486.

38. Gross-Isseroff R, Magen A, Shiloh R, et al. The 5-HT1D receptor agonist zolmitriptan for neuroleptic-induced akathisia: an open label preliminary study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(1):23-25.

39. Avital A, Gross-Isseroff R, Stryjer R, et al. Zolmitriptan compared to propranolol in the treatment of acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a comparative double-blind study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(7):476-482.

40. Rathbone J, Soares-Weiser K. Anticholinergics for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD003727.

41. Sandyk R. Successful treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with baclofen and clonazepam. A case report. Eur Neurol. 1985;24(4):286-288.

42. Miller CH, Fleischhacker W. Managing antipsychotic-induced acute and chronic akathisia. Drug Saf. 2000;22(1):73-81.

43. Pfeffer G, Chouinard G, Margolese HC. Gabapentin in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):179-181.

44. Stahl SM. Role of α1 adrenergic antagonism in the mechanism of action of iloperidone: reducing extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(6):285-258.

45. Hettema JM, Ross DE. A case of aripiprazole-related tardive akathisia and its treatment with ropinirole. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1814-1815.

Akathisia—from the Greek for “inability to sit”—is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by subjective and objective psychomotor restlessness. Patients typically experience feelings of unease, inner restlessness mainly involving the legs, and a compulsion to move. Most engage in repetitive movement. They might swing or cross and uncross their legs, shift from one foot to the other, continuously pace, or persistently fidget.

In clinical settings, akathisia usually is a side effect of medication. Antipsychotics, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and buspirone are common triggers, but akathisia also has been associated with some antiemetics, preoperative sedatives, calcium channel blockers, and antivertigo agents. It also can be caused by withdrawal from an antipsychotic or related to a substance use disorder, especially cocaine. Akathisia can be acute or chronic, occurring in a tardive form with symptoms that last >6 months.1-3

Much isn’t known about drug-induced akathisia

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of akathisia is incomplete. Some have suggested that it results from an imbalance between the dopaminergic/cholinergic and dopaminergic/serotonergic systems4; others, that the cause is a mismatch between the core and the shell of the nucleus accumbens, due in part to overstimulation of the locus ceruleus.5

More recently, researchers established a positive association between higher scores on the Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale and D2/D3 receptor occupancy in the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle).6 The D2/D3 receptor occupancy model might explain withdrawal symptoms associated with cocaine,7 as well as relative worsening of symptoms after tapering or discontinuing stimulants in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Elements of a clinical evaluation

When akathisia is suspected, evaluation by a clinician familiar with its phenomenology is crucial. A validated tool, such as the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (at out cometracker.org/library/BAS.pdf) can aid in the detection and assessment of severity.8

In evaluating patients, keep in mind that the inner restlessness that characterizes akathisia can affect the trunk, hands, and arms, as well as the legs, and can cause dysphoria and anxiety. Akathisia has been linked to an increased likelihood of developing suicidal ideation and behavior.9

Less common subjective symptoms include rage, fear, nausea, and worsening of psychotic symptoms. Because of its association with aggression and agitation, drug-induced akathisia has been cited—with little success—as the basis for an insanity defense by people who have committed a violent act.10

Or is akathisia another psychiatric disorder?

Akathisia might go undetected for several reasons. One key factor: Its symptoms resemble and often overlap with those of other psychiatric disorders, such as mania, psychosis, agitated depression, and ADHD. In addition, akathisia often occurs concurrently with, and is masked by, akinesia, a common extrapyramidal side effect of many antipsychotics. Such patients might have the inner feeling of restlessness and urge to move but do not exhibit characteristic limb movements. In some cases, cognitive or intellectual limitations prevent patients from communicating the inner turmoil they feel.11

Medication nonadherence further complicates the picture, sometimes prompting a clinician to increase the dosage of the drug that is causing akathisia (Box 112).

Managing drug-induced akathisia

Akathisia usually resolves when the drug causing it is discontinued; decreasing the dosage might alleviate the symptoms. Whenever akathisia is detected, careful revision of the current drug regimen— substituting an antipsychotic with a lower prevalence of akathisia, for example— should be considered (Box 213-16). Treatment of drug-induced akathisia, which should be tailored to the patient’s psychopathology and comorbidities, is needed as well (Table17-25).

Beta blockers, particularly propranolol, are considered first-line therapy for drug-induced akathisia, with a dosage of 20 to 40 mg twice daily used to relieve symptoms26 The effect can be explained by adrenergic terminals in the locus ceruleus and ending in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex stimulate β adrenoreceptors.5,27 Although multiple small studies and case reports26,28-32 support the use of beta blockers to treat drug-induced akathisia, the quality of evidence of their efficacy is controversial.12,21,27 Consider the risk of hypotension and bradycardia and be aware of contraindications for patients with asthma or diabetes.

Low-dose mirtazapine (15 mg/d) was found to be as effective as propranolol, 80 mg/d, in a placebo-controlled study, and to be more effective than a beta blocker in treating akathisia induced by a first-generation antipsychotic. The authors concluded that both propranolol and mirtazapine should be first-line therapy.23 Others have suggested that these results be interpreted with caution because mirtazapine (at a higher dosage) has been linked to akathisia.33 Mirtazapine blocks α-adrenergic receptors, resulting in antagonism of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors and consequent enhancement of 5-HT1A serotonergic transmission.34 In one study, it was shown to reduce binding of the D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole.35

Serotonin antagonists and agonists. Blockade of 5-HT2 receptors can attenuate D2 blockade and mitigate akathisia symptoms. Mianserin, 15 mg/d, can be helpful, and ritanserin, 5 to 20 mg/d, produced about a 50% reduction in akathisia symptoms in 10 patients taking neuroleptics.36 Neither is available in the United States, however.

Cyproheptadine, a potent 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C antagonist with anticholinergic and antihistaminic action, improved akathisia symptoms in an open trial of 17 patients with antipsychotic-induced akathisia.37 The recommended dose is 8 to 16 mg/d.

A study using the selective inverse agonist pimavanserin (not FDA-approved) decreased akathisia in healthy volunteers taking haloperidol.14,24,33

Zolmitriptan, a 5-HT1D agonist, also can be used38; one study found that 7.5 mg/d of zolmitriptan is as effective as propranolol.39

A 2010 study showed a statistically significant improvement in 8 patients taking trazodone, compared with 5 patients on placebo, all of whom met criteria for at least mild akathisia. Trazodone’s antiakathitic effect is attributed to its 5-HT2A antagonism.25

Anticholinergics. Traditionally, benztropine, biperiden, diphenhydramine, and trihexyphenidyl have been used for prevention and treatment of extrapyramidal side effects. A Cochrane review concluded, however, that data are insufficient to support use of anticholinergics for akathisia.40 Although multiple case reports have shown anticholinergics to be effective in treating drug-induced akathisia,12,17,33 their association with cognitive side effects suggests a need for caution.18

Benzodiazepines. Through their sedative and anxiolytic properties, benzodiazepines are thought to partially alleviate akathisia symptoms. Two small trials found clonazepam helpful for akathisia symptoms2,20; and 1 case report revealed that a patient with akathisia improved after coadministration of clonazepam and baclofen.41

Anticonvulsants. Valproic acid has not been found to be useful in antipsychotic-induced tardive akathisia.42 However, a case report described a patient with schizophrenia whose akathisia symptoms improved after the dosage of gabapentin was increased.43 Last, carbamazepine was found to be effective in reducing akathisia symptoms in 3 patients with schizophrenia who were resistant to beta blockers, anticholinergics, antihistaminergics, and benzodiazepines.19

α-adrenergic agonists. In an open trial, akathisia symptoms in 6 patients improved with clonidine, 0.2 to 0.8 mg/d.17 Speculation is that strong α1 antagonism might help prevent akathisia, which could be why this condition is not associated with iloperidone.44

D2 agonists. Akathisia and restless legs syndrome have similar pathophysiology,1,2 and patients with akathisia could benefit from D2 agonists such as cabergoline, pramipexole, rotigotine, and ropinirole. One case study revealed that a patient with aripiprazole-induced akathisia improved with ropinirole.45 D2 agonists can precipitate or worsen psychosis, however, and would be a relative contraindication in patients with psychotic disorders.22

Bottom Line

Failure to detect drug-induced akathisia can increase morbidity and delay recovery in patients undergoing psychiatric care. Knowing what to look for and how to tailor treatment to the needs of a given patient is an essential component of good care.

Related Resources

• Ferrando SJ, Eisendrath SJ. Adverse neuropsychiatric effects of dopamine antagonist medications. Misdiagnosis in the medical setting. Psychosomatics. 1991;32(4):426-432.

• Vinson DR. Diphenhydramine in the treatment of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):265-270.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Haloperidol • Haldol

Baclofen • Lioresal Iloperidone • Fanapt

Benztropine • Cogentin Lurasidone • Latuda

Biperiden • Akineton Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buspirone • BuSpar Pramipexole • Mirapex

Cabergoline • Dostinex Propranolol • Inderal

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Ropinirole • Requip

Clonidine • Catapres Rotigotine • Neupro

Clozapine • Clozaril Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Cyproheptadine • Periactin Trihexyphenidyl • Artane

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Valproic acid • Depakene

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zolmitriptan • Zomig

Acknowledgement

Mandy Evans, MD, assisted with editing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosure

Dr. Forcen reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Akathisia—from the Greek for “inability to sit”—is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by subjective and objective psychomotor restlessness. Patients typically experience feelings of unease, inner restlessness mainly involving the legs, and a compulsion to move. Most engage in repetitive movement. They might swing or cross and uncross their legs, shift from one foot to the other, continuously pace, or persistently fidget.

In clinical settings, akathisia usually is a side effect of medication. Antipsychotics, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and buspirone are common triggers, but akathisia also has been associated with some antiemetics, preoperative sedatives, calcium channel blockers, and antivertigo agents. It also can be caused by withdrawal from an antipsychotic or related to a substance use disorder, especially cocaine. Akathisia can be acute or chronic, occurring in a tardive form with symptoms that last >6 months.1-3

Much isn’t known about drug-induced akathisia

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of akathisia is incomplete. Some have suggested that it results from an imbalance between the dopaminergic/cholinergic and dopaminergic/serotonergic systems4; others, that the cause is a mismatch between the core and the shell of the nucleus accumbens, due in part to overstimulation of the locus ceruleus.5

More recently, researchers established a positive association between higher scores on the Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale and D2/D3 receptor occupancy in the ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle).6 The D2/D3 receptor occupancy model might explain withdrawal symptoms associated with cocaine,7 as well as relative worsening of symptoms after tapering or discontinuing stimulants in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Elements of a clinical evaluation

When akathisia is suspected, evaluation by a clinician familiar with its phenomenology is crucial. A validated tool, such as the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (at out cometracker.org/library/BAS.pdf) can aid in the detection and assessment of severity.8

In evaluating patients, keep in mind that the inner restlessness that characterizes akathisia can affect the trunk, hands, and arms, as well as the legs, and can cause dysphoria and anxiety. Akathisia has been linked to an increased likelihood of developing suicidal ideation and behavior.9

Less common subjective symptoms include rage, fear, nausea, and worsening of psychotic symptoms. Because of its association with aggression and agitation, drug-induced akathisia has been cited—with little success—as the basis for an insanity defense by people who have committed a violent act.10

Or is akathisia another psychiatric disorder?

Akathisia might go undetected for several reasons. One key factor: Its symptoms resemble and often overlap with those of other psychiatric disorders, such as mania, psychosis, agitated depression, and ADHD. In addition, akathisia often occurs concurrently with, and is masked by, akinesia, a common extrapyramidal side effect of many antipsychotics. Such patients might have the inner feeling of restlessness and urge to move but do not exhibit characteristic limb movements. In some cases, cognitive or intellectual limitations prevent patients from communicating the inner turmoil they feel.11

Medication nonadherence further complicates the picture, sometimes prompting a clinician to increase the dosage of the drug that is causing akathisia (Box 112).

Managing drug-induced akathisia

Akathisia usually resolves when the drug causing it is discontinued; decreasing the dosage might alleviate the symptoms. Whenever akathisia is detected, careful revision of the current drug regimen— substituting an antipsychotic with a lower prevalence of akathisia, for example— should be considered (Box 213-16). Treatment of drug-induced akathisia, which should be tailored to the patient’s psychopathology and comorbidities, is needed as well (Table17-25).

Beta blockers, particularly propranolol, are considered first-line therapy for drug-induced akathisia, with a dosage of 20 to 40 mg twice daily used to relieve symptoms26 The effect can be explained by adrenergic terminals in the locus ceruleus and ending in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex stimulate β adrenoreceptors.5,27 Although multiple small studies and case reports26,28-32 support the use of beta blockers to treat drug-induced akathisia, the quality of evidence of their efficacy is controversial.12,21,27 Consider the risk of hypotension and bradycardia and be aware of contraindications for patients with asthma or diabetes.

Low-dose mirtazapine (15 mg/d) was found to be as effective as propranolol, 80 mg/d, in a placebo-controlled study, and to be more effective than a beta blocker in treating akathisia induced by a first-generation antipsychotic. The authors concluded that both propranolol and mirtazapine should be first-line therapy.23 Others have suggested that these results be interpreted with caution because mirtazapine (at a higher dosage) has been linked to akathisia.33 Mirtazapine blocks α-adrenergic receptors, resulting in antagonism of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors and consequent enhancement of 5-HT1A serotonergic transmission.34 In one study, it was shown to reduce binding of the D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole.35

Serotonin antagonists and agonists. Blockade of 5-HT2 receptors can attenuate D2 blockade and mitigate akathisia symptoms. Mianserin, 15 mg/d, can be helpful, and ritanserin, 5 to 20 mg/d, produced about a 50% reduction in akathisia symptoms in 10 patients taking neuroleptics.36 Neither is available in the United States, however.

Cyproheptadine, a potent 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C antagonist with anticholinergic and antihistaminic action, improved akathisia symptoms in an open trial of 17 patients with antipsychotic-induced akathisia.37 The recommended dose is 8 to 16 mg/d.

A study using the selective inverse agonist pimavanserin (not FDA-approved) decreased akathisia in healthy volunteers taking haloperidol.14,24,33

Zolmitriptan, a 5-HT1D agonist, also can be used38; one study found that 7.5 mg/d of zolmitriptan is as effective as propranolol.39

A 2010 study showed a statistically significant improvement in 8 patients taking trazodone, compared with 5 patients on placebo, all of whom met criteria for at least mild akathisia. Trazodone’s antiakathitic effect is attributed to its 5-HT2A antagonism.25

Anticholinergics. Traditionally, benztropine, biperiden, diphenhydramine, and trihexyphenidyl have been used for prevention and treatment of extrapyramidal side effects. A Cochrane review concluded, however, that data are insufficient to support use of anticholinergics for akathisia.40 Although multiple case reports have shown anticholinergics to be effective in treating drug-induced akathisia,12,17,33 their association with cognitive side effects suggests a need for caution.18

Benzodiazepines. Through their sedative and anxiolytic properties, benzodiazepines are thought to partially alleviate akathisia symptoms. Two small trials found clonazepam helpful for akathisia symptoms2,20; and 1 case report revealed that a patient with akathisia improved after coadministration of clonazepam and baclofen.41

Anticonvulsants. Valproic acid has not been found to be useful in antipsychotic-induced tardive akathisia.42 However, a case report described a patient with schizophrenia whose akathisia symptoms improved after the dosage of gabapentin was increased.43 Last, carbamazepine was found to be effective in reducing akathisia symptoms in 3 patients with schizophrenia who were resistant to beta blockers, anticholinergics, antihistaminergics, and benzodiazepines.19

α-adrenergic agonists. In an open trial, akathisia symptoms in 6 patients improved with clonidine, 0.2 to 0.8 mg/d.17 Speculation is that strong α1 antagonism might help prevent akathisia, which could be why this condition is not associated with iloperidone.44

D2 agonists. Akathisia and restless legs syndrome have similar pathophysiology,1,2 and patients with akathisia could benefit from D2 agonists such as cabergoline, pramipexole, rotigotine, and ropinirole. One case study revealed that a patient with aripiprazole-induced akathisia improved with ropinirole.45 D2 agonists can precipitate or worsen psychosis, however, and would be a relative contraindication in patients with psychotic disorders.22

Bottom Line

Failure to detect drug-induced akathisia can increase morbidity and delay recovery in patients undergoing psychiatric care. Knowing what to look for and how to tailor treatment to the needs of a given patient is an essential component of good care.

Related Resources

• Ferrando SJ, Eisendrath SJ. Adverse neuropsychiatric effects of dopamine antagonist medications. Misdiagnosis in the medical setting. Psychosomatics. 1991;32(4):426-432.

• Vinson DR. Diphenhydramine in the treatment of akathisia induced by prochlorperazine. J Emerg Med. 2004;26(3):265-270.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify Haloperidol • Haldol

Baclofen • Lioresal Iloperidone • Fanapt

Benztropine • Cogentin Lurasidone • Latuda

Biperiden • Akineton Mirtazapine • Remeron

Buspirone • BuSpar Pramipexole • Mirapex

Cabergoline • Dostinex Propranolol • Inderal

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin Ropinirole • Requip

Clonidine • Catapres Rotigotine • Neupro

Clozapine • Clozaril Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Cyproheptadine • Periactin Trihexyphenidyl • Artane

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Valproic acid • Depakene

Gabapentin • Neurontin Zolmitriptan • Zomig

Acknowledgement

Mandy Evans, MD, assisted with editing the manuscript of this article.

Disclosure

Dr. Forcen reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Sachdev P. Akathisia and restless legs. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

2. Sachdev P, Longragan C. The present status of akathisia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(7):381-391.

3. Poyurovsky M, Hermesh H, Weizman A. Severe withdrawal akathisia following neuroleptic discontinuation successfully controlled by clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(4):283-286.

4. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Serotonin-based pharma-cotherapy for acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a new approach to an old problem. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:4-8.

5. Loonen AJ, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(1):7-10.

6. Kim JH, Son YD, Kim HK, et al. Antipsychotic-associated mental side effects and their relationship to dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in striatal subdivisions: a high-resolution PET study with [11C]raclopride. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):507-511.

7. Dailey JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptor predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315(5816):1267-1270.

8. Barnes TR, Braude WM. Akathisia variants and tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(9):874-878.

9. Seemüller F, Schennach R, Mayr A, et al. Akathisia and suicidal ideation in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(5):694-698.

10. Leong GB, Silva JA. Neuroleptic-induced akathisia and violence: a review. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(1):187-189.

11. Hirose S. The causes of underdiagnosing akathisia. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(3):547-558.

12. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):S1-S46; quiz 47-48.

13. Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879-911.

14. Poyurovsky M. Acute antipsychotic-induced akathisia revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):89-91.

15. Saltz BL, Robinson DG, Woerner MG. Recognizing and managing antipsychotic drug treatment side effects in the elderly. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(suppl 2):14-19.

16. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS. The NIMH-CATIE Schizophrenia Study: what did we learn? Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):770-775.

17. Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, Lipinski JF Jr, et al. Use of clonidine in treating neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatry Res. 1984;13(3):253-259.

18. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1055-1062.

19. Masui T, Kusumi I, Takahashi Y, et al. Efficacy of carbamazepine against neuroleptic-induced akathisia in treatment with perospirone: case series. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):343-346.

20. Lima AR, Soares-Weiser K, Bacaltchuk J, et al. Benzodiazepines for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001950.

21. Lima AR, Bacalcthuk J, Barnes TR, et al. Central action beta-blockers versus placebo for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD001946.

22. Bilal L, Ching C. Cabergoline-induced psychosis in a patient with undiagnosed depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E54.

23. Poyurovsky M, Pashinian A, Weizman A, et al. Low-dose mirtazapine: a new option in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propranolol-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry.

2006;59(11):1071-1077.

24. Maidment I. Use of serotonin antagonists in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2000;24(9):348-351.

25. Stryjer R, Rosenzcwaig S, Bar F, et al. Trazodone for the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(5):219-222.

26. Dumon JP, Catteau J, Lanvin F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled comparison of propranolol and betaxolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):647-650.

27. van Waarde A, Vaalburg W, Doze P, et al. PET imaging of beta-adrenoceptors in the human brain: a realistic goal or a mirage? Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(13):1519-1536.

28. Kurzthaler I, Hummer M, Kohl C, et al. Propranolol treatment of olanzapine-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1316.

29. Adler LA, Peselow E, Rosenthal MA, et al. A controlled comparison of the effects of propranolol, benztropine, and placebo on akathisia: an interim analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):283-286.

30. Dorevitch A, Durst R, Ginath Y. Propranolol in the treatment of akathisia caused by antipsychotic drugs. South Med J. 1991;84(12):1505-1506.

31. Lipinski JF Jr, Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, et al. Propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):412-415.

32. Adler L, Angrist B, Peselow E, et al. A controlled assessment of propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:42-45.

33. Kumar R, Sachdev PS. Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(3):293-299.

34. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(3):249-264.

35. Rogóz Z, Wróbel A, Dlaboga D, et al. Effect of repeated treatment with mirtazapine on the central dopaminergic D2/D3 receptors. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54(4):381-389.

36. Miller CH, Fleischhacker WW, Ehrmann H, et al. Treatment of neuroleptic induced akathisia with the 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26(3):373-376.

37. Weiss D, Aizenberg D, Hermesh H, et al. Cyproheptadine treatment in neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(4):483-486.

38. Gross-Isseroff R, Magen A, Shiloh R, et al. The 5-HT1D receptor agonist zolmitriptan for neuroleptic-induced akathisia: an open label preliminary study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(1):23-25.

39. Avital A, Gross-Isseroff R, Stryjer R, et al. Zolmitriptan compared to propranolol in the treatment of acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a comparative double-blind study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(7):476-482.

40. Rathbone J, Soares-Weiser K. Anticholinergics for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD003727.

41. Sandyk R. Successful treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with baclofen and clonazepam. A case report. Eur Neurol. 1985;24(4):286-288.

42. Miller CH, Fleischhacker W. Managing antipsychotic-induced acute and chronic akathisia. Drug Saf. 2000;22(1):73-81.

43. Pfeffer G, Chouinard G, Margolese HC. Gabapentin in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):179-181.

44. Stahl SM. Role of α1 adrenergic antagonism in the mechanism of action of iloperidone: reducing extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(6):285-258.

45. Hettema JM, Ross DE. A case of aripiprazole-related tardive akathisia and its treatment with ropinirole. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1814-1815.

1. Sachdev P. Akathisia and restless legs. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

2. Sachdev P, Longragan C. The present status of akathisia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(7):381-391.

3. Poyurovsky M, Hermesh H, Weizman A. Severe withdrawal akathisia following neuroleptic discontinuation successfully controlled by clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(4):283-286.

4. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A. Serotonin-based pharma-cotherapy for acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a new approach to an old problem. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:4-8.

5. Loonen AJ, Stahl SM. The mechanism of drug-induced akathisia. CNS Spectr. 2011;16(1):7-10.

6. Kim JH, Son YD, Kim HK, et al. Antipsychotic-associated mental side effects and their relationship to dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in striatal subdivisions: a high-resolution PET study with [11C]raclopride. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):507-511.

7. Dailey JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptor predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315(5816):1267-1270.

8. Barnes TR, Braude WM. Akathisia variants and tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42(9):874-878.

9. Seemüller F, Schennach R, Mayr A, et al. Akathisia and suicidal ideation in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(5):694-698.

10. Leong GB, Silva JA. Neuroleptic-induced akathisia and violence: a review. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(1):187-189.

11. Hirose S. The causes of underdiagnosing akathisia. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(3):547-558.

12. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al; Expert Consensus Panel on Adherence Problems in Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 4):S1-S46; quiz 47-48.

13. Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879-911.

14. Poyurovsky M. Acute antipsychotic-induced akathisia revisited. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):89-91.

15. Saltz BL, Robinson DG, Woerner MG. Recognizing and managing antipsychotic drug treatment side effects in the elderly. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(suppl 2):14-19.

16. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS. The NIMH-CATIE Schizophrenia Study: what did we learn? Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):770-775.

17. Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, Lipinski JF Jr, et al. Use of clonidine in treating neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatry Res. 1984;13(3):253-259.

18. Vinogradov S, Fisher M, Warm H, et al. The cognitive cost of anticholinergic burden: decreased response to cognitive training in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1055-1062.

19. Masui T, Kusumi I, Takahashi Y, et al. Efficacy of carbamazepine against neuroleptic-induced akathisia in treatment with perospirone: case series. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(2):343-346.

20. Lima AR, Soares-Weiser K, Bacaltchuk J, et al. Benzodiazepines for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001950.

21. Lima AR, Bacalcthuk J, Barnes TR, et al. Central action beta-blockers versus placebo for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD001946.

22. Bilal L, Ching C. Cabergoline-induced psychosis in a patient with undiagnosed depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E54.

23. Poyurovsky M, Pashinian A, Weizman A, et al. Low-dose mirtazapine: a new option in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propranolol-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry.

2006;59(11):1071-1077.

24. Maidment I. Use of serotonin antagonists in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2000;24(9):348-351.

25. Stryjer R, Rosenzcwaig S, Bar F, et al. Trazodone for the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(5):219-222.

26. Dumon JP, Catteau J, Lanvin F, et al. Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled comparison of propranolol and betaxolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):647-650.

27. van Waarde A, Vaalburg W, Doze P, et al. PET imaging of beta-adrenoceptors in the human brain: a realistic goal or a mirage? Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(13):1519-1536.

28. Kurzthaler I, Hummer M, Kohl C, et al. Propranolol treatment of olanzapine-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1316.

29. Adler LA, Peselow E, Rosenthal MA, et al. A controlled comparison of the effects of propranolol, benztropine, and placebo on akathisia: an interim analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):283-286.

30. Dorevitch A, Durst R, Ginath Y. Propranolol in the treatment of akathisia caused by antipsychotic drugs. South Med J. 1991;84(12):1505-1506.

31. Lipinski JF Jr, Zubenko GS, Cohen BM, et al. Propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(3):412-415.

32. Adler L, Angrist B, Peselow E, et al. A controlled assessment of propranolol in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:42-45.

33. Kumar R, Sachdev PS. Akathisia and second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(3):293-299.

34. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7(3):249-264.

35. Rogóz Z, Wróbel A, Dlaboga D, et al. Effect of repeated treatment with mirtazapine on the central dopaminergic D2/D3 receptors. Pol J Pharmacol. 2002;54(4):381-389.

36. Miller CH, Fleischhacker WW, Ehrmann H, et al. Treatment of neuroleptic induced akathisia with the 5-HT2 antagonist ritanserin. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26(3):373-376.

37. Weiss D, Aizenberg D, Hermesh H, et al. Cyproheptadine treatment in neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(4):483-486.

38. Gross-Isseroff R, Magen A, Shiloh R, et al. The 5-HT1D receptor agonist zolmitriptan for neuroleptic-induced akathisia: an open label preliminary study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(1):23-25.

39. Avital A, Gross-Isseroff R, Stryjer R, et al. Zolmitriptan compared to propranolol in the treatment of acute neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a comparative double-blind study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(7):476-482.

40. Rathbone J, Soares-Weiser K. Anticholinergics for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD003727.

41. Sandyk R. Successful treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with baclofen and clonazepam. A case report. Eur Neurol. 1985;24(4):286-288.

42. Miller CH, Fleischhacker W. Managing antipsychotic-induced acute and chronic akathisia. Drug Saf. 2000;22(1):73-81.

43. Pfeffer G, Chouinard G, Margolese HC. Gabapentin in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):179-181.

44. Stahl SM. Role of α1 adrenergic antagonism in the mechanism of action of iloperidone: reducing extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(6):285-258.

45. Hettema JM, Ross DE. A case of aripiprazole-related tardive akathisia and its treatment with ropinirole. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1814-1815.