User login

From the Rand Corporation and UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Santa Monica, CA (Dr. Ahluwalia) and University of Southern California, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Enguidanos).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the relevance of advance care planning to heart failure management, describe key advance care planning challenges, and provide clinicians with actionable guidance for engaging in advance care planning conversations.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Although most patients with heart failure prefer to receive thorough and honest information about their health condition and prognosis, the unpredictability of the heart failure trajectory coupled with physician barriers including discomfort with emotionally-laden topics and difficulty identifying the “right” time to engage in advance care planning, and systems barriers such as inadequate clinic time and limited reimbursement, impede timely engagement in advance care planning discussions. Approaches to effective advance care planning communication include using open-ended questions to stimulate patient engagement, evaluating how much information the patient wants to ensure patient-centeredness, and using empathic language to demonstrate support and understanding. While successful models of advance care planning communication have been identified, replication is limited due to the resource intense nature of these approaches.

- Conclusion: Challenges to advance care planning discussions among patients with heart failure may be mitigated through the establishment of communication quality standards as well as guidelines promoting early and ongoing advance care planning discussions, as well as reimbursement for outpatient discussions.

Heart failure, a leading cause of death, disability, and health care costs in the United States, is an incurable and life-limiting illness that is becoming increasingly prevalent due to an aging population and improved life expectancy. Approximately 5.3 million Americans are currently living with heart failure [1], with more than 550,000 new cases diagnosed each year [2]. Heart failure disproportionately affects older adults; about 80% of all cases occur in persons aged 65 years or older [3], and heart failure is the leading cause of hospital admissions among older adults [4]. The burden and impact of heart failure peaks near the end of life; 80% of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure are hospitalized in the last 6 months of life [5].

The Trajectory of Heart Failure

Patients with heart failure experience a highly variable, nonlinear clinical trajectory marked by progressive deterioration and frequent exacerbations requiring hospitalization [6]. Their prognosis, though uncertain, is poor, with reported 1-year mortality rates following a hospitalization between 30% and 50% and 5-year mortality as high as 75% [7–11], a survival rate worse than that of some cancers [12]. Patients with heart failure caused by ischemic heart disease are at high risk for sudden cardiac death, particularly at earlier stages of the disease, which can confound the ability to appropriately plan for the future [13]. Those who survive to more advanced stages of heart failure face worsening quality of life [14–16], driven by a high prevalence of fatigue, breathlessness, pain, and depression [17–24]. Indeed, patients with heart failure have a similar symptom burden to patients with advanced cancer [25]. Older adults with heart failure also have a high comorbidity burden that further complicates both symptomology and disease trajectory with implications for decision-making about life-prolonging heart failure therapies [26,27].

Advance Care Planning in Heart Failure

The unpredictable nature of heart failure makes it difficult for patients and families to plan and prepare for their future, yet it is this very uncertainty that makes advance care planning (ACP) so critical for heart failure patients. Clear and honest patient-clinician communication about ACP, including an exploration of patient values and goals for care in the context of prognostic information, is essential to patient-centered treatment decision-making [28]. This is particularly relevant in heart failure, where a range of high-intensity, invasive, and costly interventions are increasingly being applied (eg, ventricular assist devices) without equivalent attention to quality of life and patients’ long-term goals for care.

Patients with heart failure and their families face multiple complex treatment decisions along the trajectory of their illness, such as discontinuation of beta blockers among patients with refractory fluid overload or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in end-stage patients with symptomatic hypotension [29,30]. In end-stage heart failure patients, deactivation of an implantable cardiac defibrillator might be considered to avoid the pain and distress associated with repeated shocks. In contrast, other interventions such as cardiac resynchronization therapy and continuous inotropic infusion have quality of life benefits; continuation of these therapies may be appropriate even when discontinuing other interventions. Such decisions should be guided by a thorough understanding of the patient’s expressed preferences and values, ideally assessed early in the trajectory of the disease and continuously re-evaluated as the diseases progresses.

The American Heart Association supports early and regular patient-provider ACP discussions to guide heart failure patients’ future decision-making [31], and recommends that such discussions be initiated in the outpatient setting, prior to and in anticipation of clinical decline. ACP communication plays a critical role in enhancing patients’ understanding of their diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and choices in end-of-life care [31]. ACP communication also helps the clinician to better understand the context within which patients and their caregivers might make health care decisions, including their values and preferences for care. Patient-provider discussions about ACP focused on understanding patient values and initiated early in the trajectory of serious illness can support future in-the-moment decision-making, and is likely more effective than asking patients to make specific treatment decisions in advance [32]. A growing body of rigorous research has shown that ACP communication is associated with greater preference-concordant care and congruence in patient-surrogate understanding of patient preferences, lower costs, and less aggressive care at the end of life [33–37].

Patient Preferences for ACP Communication

Most patients with heart failure and their caregivers want honest disclosure regarding prognosis and to receive information about the expected trajectory of their disease [38–41] as early as possible [38] to help them plan and prepare for their future. Patients and their caregivers prefer to have these conversations with their physician [38] or other provider most familiar with the patient and family [39]. Patients also express a preference for support with dealing with the uncertainty inherent to heart failure [39]. Although most patients and caregivers desire to receive clear and honest communication about their disease, it is important to note that patients may vary in the extent of information they prefer to receive about their heart failure, with some individuals preferring not to talk about the end of life and future care needs at all [39,42–44].

Challenges to ACP Communication in Heart Failure

Despite patient and caregiver preferences for ACP communication with their providers, evidence suggests such communication occurs infrequently [40,45] and that heart failure patients may lack important information about their prognosis and treatment options [40,44,46,47]. For example, patients may not recognize the terminal nature of heart failure, and may be unaware of the range of treatment options, including hospice, available to them. Evidence also demonstrates that ACP is infrequently discussed with their health care providers [40], resulting in these conversations being avoided or deferred until an emergent clinical situation [44,48] when hasty questions about treatment choices may yield uncertain and conflicting answers not representative of a patient’s underlying values.

The infrequent, late, and often lack of discussions about ACP are driven by several challenges. First, the uncertain trajectory of heart failure makes communication regarding “what to expect” difficult. Prognostication is an immense challenge in heart failure [40,49–52], making it harder to talk about end-of-life issues and hindering the ability of patients, caregivers and health care providers to plan and prepare for the future. It is often difficult for clinicians, who face the challenge of instilling hope in the face of truthful disclosure [53], to identify the “right time” to initiate such discussions.

Second, a lack of time, particularly during outpatient visits, impedes physician ability to have considered discussions about future care needs and preferences [32,54]. The U.S. health care system currently lacks financial reimbursement for these discussions, which poses a significant barrier to the integration of ACP conversations into routine clinical practice. Moreover, these conversations are lengthy and iterative [53]. ACP discussions that are focused on facilitating patient-centered decision-making ideally begin with a discussion of expected prognosis, followed by an exploration of patient preferences and values for health care, and then a review of treatment options to be considered in the context of those preferences. Often additional time is needed for completing advance directive documents or for charting key outcomes from these discussions. Clinicians today are frequently overloaded with addressing multiple medical issues during outpatient visits that leave little time for non-medical tasks such as ACP discussions. The lack of financial incentives to support in-depth discussions is a critical challenge in improving ACP.

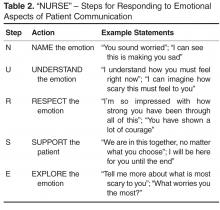

Third, a lack of training in specialized communication skills, particularly focused on empathic and emotionally sensitive disclosure, may further hinder physicians from initiating frank discussions with their patients. ACP conversations are highly sensitive and fraught with emotional complexity, and clinicians understandably experience discomfort with breaking bad news [49,51,55] or with broader issues of decline and death [51,56,57]. Physicians tend to be most comfortable addressing cognitive aspects of communication; addressing the emotional needs of patients is harder. Medical school training teaches detachment in physician practice, perhaps as a way of coping with the sadness they regularly confront and in maintaining their ability to provide clinical care. In fact, physicians describe their most difficult encounters as those with the most negative expressed emotions and miss opportunities to respond with empathy [58–60], a critical skill in effective patient-physician communication that is associated with improved patient satisfaction [61,62]. While patients value good communication skills in their health care encounters, many providers feel they lack the necessary skills to lead effective ACP discussions [49,63].

Finally, information gaps with regards to heart failure contribute to delayed or absent conversations about planning for future care. Many heart failure patients have a limited understanding of their disease [32,40,44,55], particularly an inaccurate perception that heart failure is not a terminal and life-limiting illness [42,49,64]. Compounding this is the fact that even some health care providers are reluctant to acknowledge the terminal nature of heart failure [50,56]. Without frank acknowledgement of the terminal nature of heart failure, the initiation of discussions regarding end-of-life care will remain difficult if not impossible.

Approaches to ACP in Heart Failure

When Is the Right Time?

Given the complexity and unpredictable trajectory of heart failure, indicators of disease progression, including changes in health status and health service use, may serve as useful signals to help clinicians identify the appropriate time to initiate care planning discussions. Repeated hospital admissions for heart failure are strongly associated with increased mortality. In a sample of community heart failure patients [8], median survival after the first, second, and third hospitalization was 2.4, 1.4, and 1.0 years, respectively. In light of this, a patient with 1 or more hospitalizations in a 12-month period may be an appropriate candidate for an ACP conversation. Similarly, comorbidity in patients with heart failure may signal the relevance and need for discussions about future care. In a sample of Medicare beneficiaries with advanced heart failure, an increasing burden of comorbidity was associated with significantly higher mortality, as were certain conditions (COPD, CKD, dementia, depression) and combinations of conditions (eg, CKD and dementia) [26]. Davidson and colleagues [68] suggest a list of clinical indicators signaling the need for an ACP conversation, including any of the following:

- > 1 episodes of exacerbation of heart failure leading to hospital admission

- New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure

- Decline in function and mobility

- Unexplained weight loss

- Resting pulse rate greater than 100 beats/minute

- Raised serum creatinine (> 150 µmol/L)

- Low serum sodium (< 135 mmol/L)

- Low serum albumen (< 33 g/L)

- High dose of loop diuretic (eg, furosemide ≥ 160 mg daily)

Given the considerable complexity and multisystem nature of heart failure, none of these indicators alone can signal certainty about disease progression and consequent outcomes; however, they can serve as a useful heuristic for helping clinicians identify appropriate times to raise the topic of ACP with their patients.

What Do I Say? Structuring the Conversation

Heart failure patients and their caregivers may vary in their preferences for hearing information about their disease; therefore, it is critical to open any conversation about planning for future in the context of their illness by asking what and how much information is desired. This includes evaluating how involved in decision-making the patient wants to be. Previously suggested language includes [69,70]:

- Would you like to consider all the options, or my opinion about the options that fit best with what I know about you?

- Some people like to know everything about their disease and be involved in all decision making. Others do not want all the news and would rather the doctor talk to __________. Which kind of person are you? How involved do you want to be in these decisions?

- Would you like me to tell you the full details of your condition?

- If you prefer not to hear the details, is there someone in your family who you trust to receive this information?

After establishing the patient’s preferences for hearing different types of information and level of involvement in decision-making about their care, the ask-tell-ask model [69,71] provides a useful approach to communicating with patients and their families. The conversation generally begins by asking patients what he or she understands about their illness (eg, “What do you understand about your heart failure?”; “I want to make sure we’re on the same page; what have other doctors told you?”). Building on what the patient already knows, the clinician can then disclose new information, correct misunderstandings, or confirm impressions and expectations the patient might have. In this way, information is tailored to the patient’s understanding and aimed at addressing potential knowledge gaps, all within the context of their preferences. Finally, the clinician asks the patient to describe their new understanding and whether or not they have questions or concerns (eg, “To make sure I did a good job of explaining to you, can you tell me what you now know about your condition from our conversation?”; “I know I’ve covered a lot and I want to make sure I was clear. When you get home, how are you going to explain what I’ve told you to your spouse?”). This approach encourages communication and exchange between patient and physician. Additionally, expressions of concern promote relationship building and bonding between physician and patient.

Keeping the Conversation Going

ACP communication can cover a wide range of topics beyond disease and prognostic disclosure by the provider to the patient. A critical aspect of ACP conversations is an exploration of the patient’s values and preferences, which can be used to help contextualize treatment choices and subsequently guide in-the-moment decision-making [72]. Using open-ended questions throughout the conversation gives the patient an opportunity to reflect on and communicate their wishes and values and allows them to engage in the conversation on their own terms. Examples of discussion-stimulating questions include [69,73]:

- What concerns you most about your illness?

- How is treatment going for you (your family)?

- As you think about your illness, what is the best and worst that might happen?

- What are your greatest hopes about your health?

- What has been most difficult about this illness for you?

- Looking back at your life, what has been important to you?

- At this point, what is most important for you to do?

Language

Central to this process is the use of empathic language to demonstrate support and understanding. An expression of empathy is also an appropriate way to acknowledge and share difficult emotions when it becomes hard to know where to take the conversation next. Quill and colleagues [74] suggest the following empathic responses to patients’ emotional expressions:

- I wish for that too

- It's unfortunate that things aren't different

- I am so sorry that this happened to you

- I understand how much you want that

- It must be very hard to accept the seriousness of this illness

Relatedly, the use of medical jargon in ACP conversations can increase the distance between patients and their providers, and may hinder patient understanding. Physicians may use technical language out of habit, or as an unconscious way to emotionally separate themselves from the task of delivering bad news. However, clear communication using layperson terms is the most effective approach to providing information necessary to patient-centered decision making. Explaining medical procedures in simple terms can improve understanding and help to build trust with the physician (eg, “We will perform an angioplasty – a procedure where a special tube with a balloon on the end of it is inserted into your artery to stretch it open. This will improve blood flow and relieve some of the symptoms you are currently experiencing”.)

Cultural Issues in Communication

There are various cultural issues to consider and address when conducting ACP discussions with heart failure patients and their families. Heart failure disproportionately affects certain racial and ethnic groups (eg, African Americans) [77–79], and effective management of heart failure depends on the provision of culturally sensitive information and facilitation of culturally informed self-care behaviors. There is evidence of cultural variation in preferences for information and role in decision-making. For example, most white and African-American patients prefer to be fully informed of their condition [80], whereas other cultures may focus on protecting the patient from difficult information in order to maintain hope [80–86]. Moreover, even in cultures where nondisclosure is preferred, patients may want to be told the truth in an indirect, euphemistic, or even nonverbal manner [80,87–89]. These complexities underscore the importance of taking a patient-centered approach to ACP communication, respecting individuality and autonomy while ultimately facilitating decision-making [90,91].

Are There Effective Training Programs for ACP Communication?

Effective communication skills are a critical component of ACP conversations between clinicians and their patients; however, most clinicians do not receive formal training in ACP communication and believe it to be a difficult task [92]. Strong evidence of the effectiveness of communication skills training has yet to be established, largely due to variation in the approach to training and the specification of relevant outcomes. For example, a systematic review of communication skills training courses found that some courses are effective at improving different types of communication skills related to providing support and gathering information, but these courses lacked effectiveness in improving patient satisfaction or provider burnout and distress [93]. Similarly, a range of approaches to teaching clinicians effective ACP communication skills early in their medical training have been identified [94], but considerable variation in quality preclude any conclusions from being drawn about their effectiveness.

Despite these challenges, there are some studies of communication skills training courses that have demonstrated the ability to increase providers’ use of empathic and facilitative communication (eg, use of open-ended questions) [58,95], and to increase self-efficacy and confidence among providers [96]. One particular teaching model that is increasingly used in cancer care is Oncotalk (http://depts.washington.edu/oncotalk/). Oncotalk has been shown to significantly increase clinical skills in giving bad news and facilitating the transition to palliative care. Building on this success, the program has expanded to training courses focused on the intensive care setting (http://depts.washington.edu/icutalk/) and geriatrics care [97–99]. It is important to note, however, that the considerable time and resource-intensive nature of communication training programs limits widespread implementation of any one approach into routine medical education. More attention to the type and structure of communication skills training programs are needed as well as scalable approaches to assist clinicians in developing effective ACP communication skills.

Policy Implications of ACP and Future Directions

There is growing recognition of the need to improve ACP among patients with seriously illness, including heart failure. In a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Dying in America [100], the need for clinician-patient communication about ACP was identified as a primary area of improvement. Recommendations include the establishment of communication quality standards as well as guidelines promoting early and ongoing ACP discussions. This is supported by recommendations from medical professional societies for an iterative model of ACP that follows the course of a serious illness [2,101]. At early stages of the illness, ACP might be focused on helping patients clarify their broad health care values and raise awareness of their disease and expected prognosis. As the condition progresses, ACP discussion might focus on exploring disease-specific treatment options within the context of previously expressed preferences, as well as identifying changes in patients’ values over time, particularly as they gain experience with their illness and health status changes [102]. In late stages of the disease, ACP might focus on documenting specific treatment choices (eg, DNR orders) and on exploring options such as palliative care, while also ensuring that patients and caregivers are appropriately prepared for imminent decline and death.

The IOM report also calls for payment reforms to include reimbursement for outpatient ACP discussions [100]. There is burgeoning national support for developing reimbursement models for ACP discussions. The American Medical Association has recently released current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for ACP services, a first step toward urging Medicare to consider reimbursement for ACP discussions with physicians.

Finally, the IOM report calls for improved education and training in ACP communication across all disciplines and specialties providing care to patients with serious illness. These recommendations bring national attention to the current limitations surrounding ACP discussions for those with serious illness, including heart failure. Further research is needed to identify methods and care models to address the gap in communication skills, processes, and policies.

Corresponding author: Sangeeta C. Ahluwalia, Rand Corporation, 1776 Main St., Santa Monica, CA, 90401, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, SCA, SE; analysis and interpretation of data, SCA, SE; drafting of article, SCA, SE; critical revision of the article, SCA, SE.

1. American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update. [Internet]. Available at www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1200078608862HS_Stats%202008.final.pdf.

2. Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult—summary article. Circulation 2005;112:1825–52.

3. Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM. The burden of chronic congestive heart failure in older persons: magnitude and implications for policy and research. Heart Fail Rev 2002;7:9–16.

4. McMurray JJ PM. Heart failure. Lancet 2005;365:1877–89.

5. Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000-2007. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:196–203.

6. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003;289:2387–92.

7. Ko D, Alter D, Austin P, et al. Life expectancy after an index hospitalization for patients with heart failure: A population-based study. Am Heart J 2008;155:324–31.

8. Setoguchi S, Stevenson LW, Schneeweiss S. Repeated hospitalizations predict mortality in the community population with heart failure. Am Heart J 2007;154:260–6.

9. Jong P, Vowinskel E, Liu PP, et al. Prognosis and determinants for survival in patients newly hospitalized for heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1689-94.

10. Thom T, Haase N, Rodamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics- 2006 update. Circulation 2006;113:e85-e151.

11. Shahar E, Lee S, Kim J, et al. Hospitalized heart failure: Rates and long-term mortality. J Card Fail 2004;10:374–9.

12. Kirkpatrick JN, Guger CJ, Arnsdorf MF, et al. Advance directives in the cardiac care unit. Am Heart J 2007;154:477–81.

13. Orn S, Dickstein K. How do heart failure patients die? Eur Heart J. 2002;4(suppl D).

14. Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic disease and relation to functional variables. Heart 2002;87:235–41.

15. Steptoe A, Mohabir A, Mahon NG, et al. Health related quality of life and psychological wellbeing in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 2000;83:645–50.

16. Johansson P, Agnebrink M, Dahlstrom U, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure, form a nursing perspective--a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;3:7–20.

17. Levenson J, McCarthy E, Lynn J, et al. The last six months of life for patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(Suppl 5):S101–S109.

18. Sullivan M, Levy W, Russo J, Spertus J. Depression and health status in patients with advanced heart failure: a prospective study in tertiary care. J Card Fail 2004;10:390–6.

19. Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2007;13:643–8.

20. Godfrey CM, Harrison MB, Friedberg E, et al. The symptom of pain in individuals recently hospitalized for heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2007;22:368–74.

21. McCarthy M, Lay M, Addington-Hall J. Dying from heart disease. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1996;30:325–8.

22. Norgren L SS. Symptoms experienced in the last six months of life in patients with end-stage heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2003;2:213–7.

23. Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, et al. Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005;4:198–206.

24. Walke LM, Byers AL, Tinetti ME, et al. Range and severity of symptoms over time among older adults wih chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2503–8.

25. Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: a comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:592–8.

26. Ahluwalia SC, Gross CP, Chaudhry SI, et al. Impact of comorbidity on mortality among older persons with advanced heart failure. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:513–9.

27. Ahluwalia SC, Gross CP, Chaudhry SI, et al. Change in comorbidity prevalence with advancing age among persons with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1145–51.

28. Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, Kohn LT, et al. A new health system for the 21st century. crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press; 2001.

29. Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:946–50.

30. Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1233–40.

31. Janssen DJ, Engelberg RA, Wouters EF, Curtis JR. Advance care planning for patients with COPD: past, present and future. Patient Educ Couns 2012;86:19–24.

32. Aldred H, Gott M, Gariballa S. Advanced heart failure: Impact on older patients and informal carers. J Adv Nurs 2005;49:116–24.

33. Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480–8.

34. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–73.

35. Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2715–7.

36. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345.

37. Schwartz CE, Wheeler HB, Hammes B, et al. Early intervention in planning end-of-life care with ambulatory geriatric patients: results of a pilot trial. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1611–8.

38. Caldwell PH, Arthur HM, Demers C. Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can J Cardiol 2007;23:791–6.

39. Bekelman DB, Nowels Ct, Retrum JH, et al. Giving voice to patients’ and family caregivers’ needs in chronic heart failure: implications for palliative care programs. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1317–24.

40. Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:149–56.

41. Strachan PH, Ross H, Dodek PM, et al. Mind the gap: opportunities for improving end-of-life care for patients with advanced heart failure. Can J Cardiol 2009;25:635–40.

42. Ågård A, Hermerén G, Herlitz J. When is a patient with heart failure adequately informed? A study of patients’ knowledge of and attitudes toward medical information. Heart Lung 2004;33:219–26.

43. Gott M, Small N, Barnes S, et al. Older people’s views of a good death in heart failure: implications for palliative care provision. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:1113–21.

44. Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002;325:929.

45. Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, et al. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:445–51.

46. Rodriguez KL, Appelt CJ, Switzer GE, et al. “They diagnosed bad heart”: a qualitative exploration of patients’ knowledge about and experiences with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37:257–65.

47. Remme WJ,McMurray JJ, Rauch B, et al. Public awareness of heart failure in Europe: first results from SHAPE. Eur Heart J 2005;22:2413e21.

48. Golin CE, Wenger NS, Liu H, et al. A prospective study of patient-physician communication about resuscitation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(5 Suppl):S52–60.

49. Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, et al. Improving end of life care for patients with chronic heart failure: ‘let’s hope it’ll get better when I know in my heart of hearts it won’t’. Heart 2007;93:963–7.

50. Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Communication in heart failure: Perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Comm 2006;14:482–90.

51. Brännström M, Ekman I, Norberg A, et al. Living with severe chronic heart failure in palliative advanced home care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006;5:295–302.

52. Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, et al. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e49–62.

53. Whitney SN, McCullough LB, Fruge E, et al. Beyond breaking bad news: the roles of hope and hopefulness. Cancer 2008;113:442–5.

54. Tung EE, North F. Advance care planning in the primary care setting: a comparison of attending staff and resident barriers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2009;26:456–63.

55. Boyd K, Murray S, Kendall M, et al. Living with advanced heart failure: A prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail 2004;6:585–91.

56. Borbasi S, Wotton K, Redden M, et al. Letting go: A qualitative study of acute care and community nurses’ perceptions of a ‘good’ versus a ‘bad’ death. Austr Crit Care 2005 2005;18:104–13.

57. Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctors’ perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: Focus group study. BMJ 2002;325:581–5.

58. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Efficacy of a communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:650–6.

59. Platt F, Keller V. Empathic communication: a teachable and learnable skill. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:222–6.

60. Morse D, Edwardsen E, Gordon H. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med 2008;22;168:1853–8.

61. Epstein R, Hadee T, Carroll J, et al. “Could this be something serious?” reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients’ expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1731–9.

62. Stewart M. What is a successful doctor-patient interview? A study of interactions and outcomes. Soc Sci Med 1984;19:

167–75.

63. Wotton K, Borbasi S, Redden M. When all else has failed. Nurses’ perception of factors influencing palliative care for patients with end-stage heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005;20:18–25.

64. Willems DL, Hak A, Visser F, Van der Wal G. Thoughts of patients with advanced heart failure on dying. Palliat Med 2004;18:564–72.

65. Briggs L, Kirchhoff K, Hammes B, et al. Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: a pilot study. J Prof Nurs 2004;20:47–58.

66. Hammes B, Rooney B. Death and EOL planning in one midwestern community. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:390.

67. Lilly C, DeMeo D, Sonna L, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med 2000;109:469–75.

68. Davidson P, Macdonald P, Newton P, et al. End stage heart failure patients: Palliative care in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:920.

69. Goodlin S, Quill T, Arnold R. Communication and decision-making about prognosis in heart failure care. J Card Fail 2008;14:106–13.

70. Analysis of U.S. hospital palliative care programs 2010 snapshot. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). Accessed 24 Nov 2014 at www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/analysis-of-us-hospital-palliative-care-programs-2010-snapshot.pdf.

71. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:164–77.

72. Sudore RL, Fried TR, Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:256–61.

73. Lo B, Quill T, Tulsky J. Discussing palliative care with patients. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:744–9.

74. Quill T, Arnold R, Platt F. I wish things were different: Expressing wishes in response to loss, futility, and unrealistic hopes. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:551–5.

75. Pollak K, Arnold R, Jeffreys A, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5748–52.

76. Back AL, Anderson WG, Bunch L, et al. Communication about cancer near the end of life. Cancer 2008;113(S7):1897–910.

77. Dries D, Exner D, Gersh B, et al. Racial differences in the outcome of left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 1999;340:609–16.

78. Alexander M, Grumbach K, Selby J, et al. Hospitalization for congestive heart failure. Explaining racial differences. JAMA 1995;274:1037–42.

79. Afzal A, Ananthasubramaniam K, Sharma N, et al. Racial differences in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol 1999;22:791–4.

80. Blackhall L, Murphy S, Frank G, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–5.

81. Huang X, Butow P, Meiser B, et al. Attitudes and information needs of chinese migrant cancer patients and their relatives. Aust N Z J Med 1999;29:207–13.

82. Tan T, Teo F, Wong K, et al. Cancer: to tell or not to tell? Singapore Med J 1993;34:202–3.

83. Gorgaki S, Kalaidopoulou O, Liarmakopoulos I, et al. Nurses’ attitudes toward truthful communication with patients with cancer. A Greek study. Cancer Nurs 2002;25:436–41.

84. Harris J, Shao J, Sugarman J. Disclosure of cancer diagnosis and prognosis in northern Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:905–13.

85. Goldstein D, Thewes B, Butow P. Communicating in a multicultural society. II: Greek community attitudes towards cancer in Australia. Intern Med J 2002;32:289–96.

86. Beyene Y. Medical disclosure and refugees. Telling bad news to Ethiopian patients. West J Med 1992;157:328–32.

87. Matsumura S, Bito S, Liu H, et al. Acculturation of attitudes toward end-of-life care: A cross-cultural survey of Japanese Americans and Japanese. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:531–9.

88. Yick AG, Gupta R. Chinese cultural dimensions of death, dying, and bereavement: Focus group findings. J Cult Divers 2002 Summer;9:32–42.

89. Frank G, Blackhall L, Murphy S, et al. Ambiguity and hope: Disclosure preferences of less acculturated elderly Mexican Americans concerning terminal cancer—A case story. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2002;11:117–26.

90. Hern HJ, Koenig B, Moore L, et al. The difference that culture can make in end-of-life decisionmaking. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 1998;7:27–48.

91. Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med 2003;78:577–87.

92. Barnett MM, Fisher JD, Cooke H, et al. Breaking bad news: consultants’ experience, previous education, and views on educational format and timing. Med Educ 2007;41:947–56.

93. Moore P, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, Lawrie T. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3CD003751.

94. Alelwani S, Ahmed Y. Medical training for communication of bad news: A literature review. J Educ Health Promot 2014;3

95. Delvaux N, Razavi D, Marchal S, et al. Effects of a 105 hour psychological training program on attitudes, communication skills and occupational stress in oncology: a randomised study. Br J Cancer 2004;90:106–14.

96. Baile WF, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, et al. Improving physician-patient communication in cancer care: Outcome of a workshop for oncologists. J Cancer Educ 1997;12:166–73.

97. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:453–60.

98. Gelfman LP, Lindenberger E, Fernandez H, et al. The effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course: a real-time assessment of skill acquisition and deliberate practice. J Pain Sympt Manage 2014;48:738–44.

99. Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, et al. Geritalk: communication skills training for geriatric and palliative medicine fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:332–7.

100. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014.

101. Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:1928–52.

102. Ditto PH, Jacobson JA, Smucker WD, et al. Context changes choices: a prospective study of the effects of hospitalization on life-sustaining treatment preferences. Med Decis Making 2006;26:313–22.

From the Rand Corporation and UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Santa Monica, CA (Dr. Ahluwalia) and University of Southern California, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Enguidanos).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the relevance of advance care planning to heart failure management, describe key advance care planning challenges, and provide clinicians with actionable guidance for engaging in advance care planning conversations.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Although most patients with heart failure prefer to receive thorough and honest information about their health condition and prognosis, the unpredictability of the heart failure trajectory coupled with physician barriers including discomfort with emotionally-laden topics and difficulty identifying the “right” time to engage in advance care planning, and systems barriers such as inadequate clinic time and limited reimbursement, impede timely engagement in advance care planning discussions. Approaches to effective advance care planning communication include using open-ended questions to stimulate patient engagement, evaluating how much information the patient wants to ensure patient-centeredness, and using empathic language to demonstrate support and understanding. While successful models of advance care planning communication have been identified, replication is limited due to the resource intense nature of these approaches.

- Conclusion: Challenges to advance care planning discussions among patients with heart failure may be mitigated through the establishment of communication quality standards as well as guidelines promoting early and ongoing advance care planning discussions, as well as reimbursement for outpatient discussions.

Heart failure, a leading cause of death, disability, and health care costs in the United States, is an incurable and life-limiting illness that is becoming increasingly prevalent due to an aging population and improved life expectancy. Approximately 5.3 million Americans are currently living with heart failure [1], with more than 550,000 new cases diagnosed each year [2]. Heart failure disproportionately affects older adults; about 80% of all cases occur in persons aged 65 years or older [3], and heart failure is the leading cause of hospital admissions among older adults [4]. The burden and impact of heart failure peaks near the end of life; 80% of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure are hospitalized in the last 6 months of life [5].

The Trajectory of Heart Failure

Patients with heart failure experience a highly variable, nonlinear clinical trajectory marked by progressive deterioration and frequent exacerbations requiring hospitalization [6]. Their prognosis, though uncertain, is poor, with reported 1-year mortality rates following a hospitalization between 30% and 50% and 5-year mortality as high as 75% [7–11], a survival rate worse than that of some cancers [12]. Patients with heart failure caused by ischemic heart disease are at high risk for sudden cardiac death, particularly at earlier stages of the disease, which can confound the ability to appropriately plan for the future [13]. Those who survive to more advanced stages of heart failure face worsening quality of life [14–16], driven by a high prevalence of fatigue, breathlessness, pain, and depression [17–24]. Indeed, patients with heart failure have a similar symptom burden to patients with advanced cancer [25]. Older adults with heart failure also have a high comorbidity burden that further complicates both symptomology and disease trajectory with implications for decision-making about life-prolonging heart failure therapies [26,27].

Advance Care Planning in Heart Failure

The unpredictable nature of heart failure makes it difficult for patients and families to plan and prepare for their future, yet it is this very uncertainty that makes advance care planning (ACP) so critical for heart failure patients. Clear and honest patient-clinician communication about ACP, including an exploration of patient values and goals for care in the context of prognostic information, is essential to patient-centered treatment decision-making [28]. This is particularly relevant in heart failure, where a range of high-intensity, invasive, and costly interventions are increasingly being applied (eg, ventricular assist devices) without equivalent attention to quality of life and patients’ long-term goals for care.

Patients with heart failure and their families face multiple complex treatment decisions along the trajectory of their illness, such as discontinuation of beta blockers among patients with refractory fluid overload or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in end-stage patients with symptomatic hypotension [29,30]. In end-stage heart failure patients, deactivation of an implantable cardiac defibrillator might be considered to avoid the pain and distress associated with repeated shocks. In contrast, other interventions such as cardiac resynchronization therapy and continuous inotropic infusion have quality of life benefits; continuation of these therapies may be appropriate even when discontinuing other interventions. Such decisions should be guided by a thorough understanding of the patient’s expressed preferences and values, ideally assessed early in the trajectory of the disease and continuously re-evaluated as the diseases progresses.

The American Heart Association supports early and regular patient-provider ACP discussions to guide heart failure patients’ future decision-making [31], and recommends that such discussions be initiated in the outpatient setting, prior to and in anticipation of clinical decline. ACP communication plays a critical role in enhancing patients’ understanding of their diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and choices in end-of-life care [31]. ACP communication also helps the clinician to better understand the context within which patients and their caregivers might make health care decisions, including their values and preferences for care. Patient-provider discussions about ACP focused on understanding patient values and initiated early in the trajectory of serious illness can support future in-the-moment decision-making, and is likely more effective than asking patients to make specific treatment decisions in advance [32]. A growing body of rigorous research has shown that ACP communication is associated with greater preference-concordant care and congruence in patient-surrogate understanding of patient preferences, lower costs, and less aggressive care at the end of life [33–37].

Patient Preferences for ACP Communication

Most patients with heart failure and their caregivers want honest disclosure regarding prognosis and to receive information about the expected trajectory of their disease [38–41] as early as possible [38] to help them plan and prepare for their future. Patients and their caregivers prefer to have these conversations with their physician [38] or other provider most familiar with the patient and family [39]. Patients also express a preference for support with dealing with the uncertainty inherent to heart failure [39]. Although most patients and caregivers desire to receive clear and honest communication about their disease, it is important to note that patients may vary in the extent of information they prefer to receive about their heart failure, with some individuals preferring not to talk about the end of life and future care needs at all [39,42–44].

Challenges to ACP Communication in Heart Failure

Despite patient and caregiver preferences for ACP communication with their providers, evidence suggests such communication occurs infrequently [40,45] and that heart failure patients may lack important information about their prognosis and treatment options [40,44,46,47]. For example, patients may not recognize the terminal nature of heart failure, and may be unaware of the range of treatment options, including hospice, available to them. Evidence also demonstrates that ACP is infrequently discussed with their health care providers [40], resulting in these conversations being avoided or deferred until an emergent clinical situation [44,48] when hasty questions about treatment choices may yield uncertain and conflicting answers not representative of a patient’s underlying values.

The infrequent, late, and often lack of discussions about ACP are driven by several challenges. First, the uncertain trajectory of heart failure makes communication regarding “what to expect” difficult. Prognostication is an immense challenge in heart failure [40,49–52], making it harder to talk about end-of-life issues and hindering the ability of patients, caregivers and health care providers to plan and prepare for the future. It is often difficult for clinicians, who face the challenge of instilling hope in the face of truthful disclosure [53], to identify the “right time” to initiate such discussions.

Second, a lack of time, particularly during outpatient visits, impedes physician ability to have considered discussions about future care needs and preferences [32,54]. The U.S. health care system currently lacks financial reimbursement for these discussions, which poses a significant barrier to the integration of ACP conversations into routine clinical practice. Moreover, these conversations are lengthy and iterative [53]. ACP discussions that are focused on facilitating patient-centered decision-making ideally begin with a discussion of expected prognosis, followed by an exploration of patient preferences and values for health care, and then a review of treatment options to be considered in the context of those preferences. Often additional time is needed for completing advance directive documents or for charting key outcomes from these discussions. Clinicians today are frequently overloaded with addressing multiple medical issues during outpatient visits that leave little time for non-medical tasks such as ACP discussions. The lack of financial incentives to support in-depth discussions is a critical challenge in improving ACP.

Third, a lack of training in specialized communication skills, particularly focused on empathic and emotionally sensitive disclosure, may further hinder physicians from initiating frank discussions with their patients. ACP conversations are highly sensitive and fraught with emotional complexity, and clinicians understandably experience discomfort with breaking bad news [49,51,55] or with broader issues of decline and death [51,56,57]. Physicians tend to be most comfortable addressing cognitive aspects of communication; addressing the emotional needs of patients is harder. Medical school training teaches detachment in physician practice, perhaps as a way of coping with the sadness they regularly confront and in maintaining their ability to provide clinical care. In fact, physicians describe their most difficult encounters as those with the most negative expressed emotions and miss opportunities to respond with empathy [58–60], a critical skill in effective patient-physician communication that is associated with improved patient satisfaction [61,62]. While patients value good communication skills in their health care encounters, many providers feel they lack the necessary skills to lead effective ACP discussions [49,63].

Finally, information gaps with regards to heart failure contribute to delayed or absent conversations about planning for future care. Many heart failure patients have a limited understanding of their disease [32,40,44,55], particularly an inaccurate perception that heart failure is not a terminal and life-limiting illness [42,49,64]. Compounding this is the fact that even some health care providers are reluctant to acknowledge the terminal nature of heart failure [50,56]. Without frank acknowledgement of the terminal nature of heart failure, the initiation of discussions regarding end-of-life care will remain difficult if not impossible.

Approaches to ACP in Heart Failure

When Is the Right Time?

Given the complexity and unpredictable trajectory of heart failure, indicators of disease progression, including changes in health status and health service use, may serve as useful signals to help clinicians identify the appropriate time to initiate care planning discussions. Repeated hospital admissions for heart failure are strongly associated with increased mortality. In a sample of community heart failure patients [8], median survival after the first, second, and third hospitalization was 2.4, 1.4, and 1.0 years, respectively. In light of this, a patient with 1 or more hospitalizations in a 12-month period may be an appropriate candidate for an ACP conversation. Similarly, comorbidity in patients with heart failure may signal the relevance and need for discussions about future care. In a sample of Medicare beneficiaries with advanced heart failure, an increasing burden of comorbidity was associated with significantly higher mortality, as were certain conditions (COPD, CKD, dementia, depression) and combinations of conditions (eg, CKD and dementia) [26]. Davidson and colleagues [68] suggest a list of clinical indicators signaling the need for an ACP conversation, including any of the following:

- > 1 episodes of exacerbation of heart failure leading to hospital admission

- New York Heart Association Class IV heart failure

- Decline in function and mobility

- Unexplained weight loss

- Resting pulse rate greater than 100 beats/minute

- Raised serum creatinine (> 150 µmol/L)

- Low serum sodium (< 135 mmol/L)

- Low serum albumen (< 33 g/L)

- High dose of loop diuretic (eg, furosemide ≥ 160 mg daily)

Given the considerable complexity and multisystem nature of heart failure, none of these indicators alone can signal certainty about disease progression and consequent outcomes; however, they can serve as a useful heuristic for helping clinicians identify appropriate times to raise the topic of ACP with their patients.

What Do I Say? Structuring the Conversation

Heart failure patients and their caregivers may vary in their preferences for hearing information about their disease; therefore, it is critical to open any conversation about planning for future in the context of their illness by asking what and how much information is desired. This includes evaluating how involved in decision-making the patient wants to be. Previously suggested language includes [69,70]:

- Would you like to consider all the options, or my opinion about the options that fit best with what I know about you?

- Some people like to know everything about their disease and be involved in all decision making. Others do not want all the news and would rather the doctor talk to __________. Which kind of person are you? How involved do you want to be in these decisions?

- Would you like me to tell you the full details of your condition?

- If you prefer not to hear the details, is there someone in your family who you trust to receive this information?

After establishing the patient’s preferences for hearing different types of information and level of involvement in decision-making about their care, the ask-tell-ask model [69,71] provides a useful approach to communicating with patients and their families. The conversation generally begins by asking patients what he or she understands about their illness (eg, “What do you understand about your heart failure?”; “I want to make sure we’re on the same page; what have other doctors told you?”). Building on what the patient already knows, the clinician can then disclose new information, correct misunderstandings, or confirm impressions and expectations the patient might have. In this way, information is tailored to the patient’s understanding and aimed at addressing potential knowledge gaps, all within the context of their preferences. Finally, the clinician asks the patient to describe their new understanding and whether or not they have questions or concerns (eg, “To make sure I did a good job of explaining to you, can you tell me what you now know about your condition from our conversation?”; “I know I’ve covered a lot and I want to make sure I was clear. When you get home, how are you going to explain what I’ve told you to your spouse?”). This approach encourages communication and exchange between patient and physician. Additionally, expressions of concern promote relationship building and bonding between physician and patient.

Keeping the Conversation Going

ACP communication can cover a wide range of topics beyond disease and prognostic disclosure by the provider to the patient. A critical aspect of ACP conversations is an exploration of the patient’s values and preferences, which can be used to help contextualize treatment choices and subsequently guide in-the-moment decision-making [72]. Using open-ended questions throughout the conversation gives the patient an opportunity to reflect on and communicate their wishes and values and allows them to engage in the conversation on their own terms. Examples of discussion-stimulating questions include [69,73]:

- What concerns you most about your illness?

- How is treatment going for you (your family)?

- As you think about your illness, what is the best and worst that might happen?

- What are your greatest hopes about your health?

- What has been most difficult about this illness for you?

- Looking back at your life, what has been important to you?

- At this point, what is most important for you to do?

Language

Central to this process is the use of empathic language to demonstrate support and understanding. An expression of empathy is also an appropriate way to acknowledge and share difficult emotions when it becomes hard to know where to take the conversation next. Quill and colleagues [74] suggest the following empathic responses to patients’ emotional expressions:

- I wish for that too

- It's unfortunate that things aren't different

- I am so sorry that this happened to you

- I understand how much you want that

- It must be very hard to accept the seriousness of this illness

Relatedly, the use of medical jargon in ACP conversations can increase the distance between patients and their providers, and may hinder patient understanding. Physicians may use technical language out of habit, or as an unconscious way to emotionally separate themselves from the task of delivering bad news. However, clear communication using layperson terms is the most effective approach to providing information necessary to patient-centered decision making. Explaining medical procedures in simple terms can improve understanding and help to build trust with the physician (eg, “We will perform an angioplasty – a procedure where a special tube with a balloon on the end of it is inserted into your artery to stretch it open. This will improve blood flow and relieve some of the symptoms you are currently experiencing”.)

Cultural Issues in Communication

There are various cultural issues to consider and address when conducting ACP discussions with heart failure patients and their families. Heart failure disproportionately affects certain racial and ethnic groups (eg, African Americans) [77–79], and effective management of heart failure depends on the provision of culturally sensitive information and facilitation of culturally informed self-care behaviors. There is evidence of cultural variation in preferences for information and role in decision-making. For example, most white and African-American patients prefer to be fully informed of their condition [80], whereas other cultures may focus on protecting the patient from difficult information in order to maintain hope [80–86]. Moreover, even in cultures where nondisclosure is preferred, patients may want to be told the truth in an indirect, euphemistic, or even nonverbal manner [80,87–89]. These complexities underscore the importance of taking a patient-centered approach to ACP communication, respecting individuality and autonomy while ultimately facilitating decision-making [90,91].

Are There Effective Training Programs for ACP Communication?

Effective communication skills are a critical component of ACP conversations between clinicians and their patients; however, most clinicians do not receive formal training in ACP communication and believe it to be a difficult task [92]. Strong evidence of the effectiveness of communication skills training has yet to be established, largely due to variation in the approach to training and the specification of relevant outcomes. For example, a systematic review of communication skills training courses found that some courses are effective at improving different types of communication skills related to providing support and gathering information, but these courses lacked effectiveness in improving patient satisfaction or provider burnout and distress [93]. Similarly, a range of approaches to teaching clinicians effective ACP communication skills early in their medical training have been identified [94], but considerable variation in quality preclude any conclusions from being drawn about their effectiveness.

Despite these challenges, there are some studies of communication skills training courses that have demonstrated the ability to increase providers’ use of empathic and facilitative communication (eg, use of open-ended questions) [58,95], and to increase self-efficacy and confidence among providers [96]. One particular teaching model that is increasingly used in cancer care is Oncotalk (http://depts.washington.edu/oncotalk/). Oncotalk has been shown to significantly increase clinical skills in giving bad news and facilitating the transition to palliative care. Building on this success, the program has expanded to training courses focused on the intensive care setting (http://depts.washington.edu/icutalk/) and geriatrics care [97–99]. It is important to note, however, that the considerable time and resource-intensive nature of communication training programs limits widespread implementation of any one approach into routine medical education. More attention to the type and structure of communication skills training programs are needed as well as scalable approaches to assist clinicians in developing effective ACP communication skills.

Policy Implications of ACP and Future Directions

There is growing recognition of the need to improve ACP among patients with seriously illness, including heart failure. In a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Dying in America [100], the need for clinician-patient communication about ACP was identified as a primary area of improvement. Recommendations include the establishment of communication quality standards as well as guidelines promoting early and ongoing ACP discussions. This is supported by recommendations from medical professional societies for an iterative model of ACP that follows the course of a serious illness [2,101]. At early stages of the illness, ACP might be focused on helping patients clarify their broad health care values and raise awareness of their disease and expected prognosis. As the condition progresses, ACP discussion might focus on exploring disease-specific treatment options within the context of previously expressed preferences, as well as identifying changes in patients’ values over time, particularly as they gain experience with their illness and health status changes [102]. In late stages of the disease, ACP might focus on documenting specific treatment choices (eg, DNR orders) and on exploring options such as palliative care, while also ensuring that patients and caregivers are appropriately prepared for imminent decline and death.

The IOM report also calls for payment reforms to include reimbursement for outpatient ACP discussions [100]. There is burgeoning national support for developing reimbursement models for ACP discussions. The American Medical Association has recently released current procedural terminology (CPT) codes for ACP services, a first step toward urging Medicare to consider reimbursement for ACP discussions with physicians.

Finally, the IOM report calls for improved education and training in ACP communication across all disciplines and specialties providing care to patients with serious illness. These recommendations bring national attention to the current limitations surrounding ACP discussions for those with serious illness, including heart failure. Further research is needed to identify methods and care models to address the gap in communication skills, processes, and policies.

Corresponding author: Sangeeta C. Ahluwalia, Rand Corporation, 1776 Main St., Santa Monica, CA, 90401, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, SCA, SE; analysis and interpretation of data, SCA, SE; drafting of article, SCA, SE; critical revision of the article, SCA, SE.

From the Rand Corporation and UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Santa Monica, CA (Dr. Ahluwalia) and University of Southern California, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Enguidanos).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the relevance of advance care planning to heart failure management, describe key advance care planning challenges, and provide clinicians with actionable guidance for engaging in advance care planning conversations.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Although most patients with heart failure prefer to receive thorough and honest information about their health condition and prognosis, the unpredictability of the heart failure trajectory coupled with physician barriers including discomfort with emotionally-laden topics and difficulty identifying the “right” time to engage in advance care planning, and systems barriers such as inadequate clinic time and limited reimbursement, impede timely engagement in advance care planning discussions. Approaches to effective advance care planning communication include using open-ended questions to stimulate patient engagement, evaluating how much information the patient wants to ensure patient-centeredness, and using empathic language to demonstrate support and understanding. While successful models of advance care planning communication have been identified, replication is limited due to the resource intense nature of these approaches.

- Conclusion: Challenges to advance care planning discussions among patients with heart failure may be mitigated through the establishment of communication quality standards as well as guidelines promoting early and ongoing advance care planning discussions, as well as reimbursement for outpatient discussions.

Heart failure, a leading cause of death, disability, and health care costs in the United States, is an incurable and life-limiting illness that is becoming increasingly prevalent due to an aging population and improved life expectancy. Approximately 5.3 million Americans are currently living with heart failure [1], with more than 550,000 new cases diagnosed each year [2]. Heart failure disproportionately affects older adults; about 80% of all cases occur in persons aged 65 years or older [3], and heart failure is the leading cause of hospital admissions among older adults [4]. The burden and impact of heart failure peaks near the end of life; 80% of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure are hospitalized in the last 6 months of life [5].

The Trajectory of Heart Failure

Patients with heart failure experience a highly variable, nonlinear clinical trajectory marked by progressive deterioration and frequent exacerbations requiring hospitalization [6]. Their prognosis, though uncertain, is poor, with reported 1-year mortality rates following a hospitalization between 30% and 50% and 5-year mortality as high as 75% [7–11], a survival rate worse than that of some cancers [12]. Patients with heart failure caused by ischemic heart disease are at high risk for sudden cardiac death, particularly at earlier stages of the disease, which can confound the ability to appropriately plan for the future [13]. Those who survive to more advanced stages of heart failure face worsening quality of life [14–16], driven by a high prevalence of fatigue, breathlessness, pain, and depression [17–24]. Indeed, patients with heart failure have a similar symptom burden to patients with advanced cancer [25]. Older adults with heart failure also have a high comorbidity burden that further complicates both symptomology and disease trajectory with implications for decision-making about life-prolonging heart failure therapies [26,27].

Advance Care Planning in Heart Failure

The unpredictable nature of heart failure makes it difficult for patients and families to plan and prepare for their future, yet it is this very uncertainty that makes advance care planning (ACP) so critical for heart failure patients. Clear and honest patient-clinician communication about ACP, including an exploration of patient values and goals for care in the context of prognostic information, is essential to patient-centered treatment decision-making [28]. This is particularly relevant in heart failure, where a range of high-intensity, invasive, and costly interventions are increasingly being applied (eg, ventricular assist devices) without equivalent attention to quality of life and patients’ long-term goals for care.

Patients with heart failure and their families face multiple complex treatment decisions along the trajectory of their illness, such as discontinuation of beta blockers among patients with refractory fluid overload or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in end-stage patients with symptomatic hypotension [29,30]. In end-stage heart failure patients, deactivation of an implantable cardiac defibrillator might be considered to avoid the pain and distress associated with repeated shocks. In contrast, other interventions such as cardiac resynchronization therapy and continuous inotropic infusion have quality of life benefits; continuation of these therapies may be appropriate even when discontinuing other interventions. Such decisions should be guided by a thorough understanding of the patient’s expressed preferences and values, ideally assessed early in the trajectory of the disease and continuously re-evaluated as the diseases progresses.

The American Heart Association supports early and regular patient-provider ACP discussions to guide heart failure patients’ future decision-making [31], and recommends that such discussions be initiated in the outpatient setting, prior to and in anticipation of clinical decline. ACP communication plays a critical role in enhancing patients’ understanding of their diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and choices in end-of-life care [31]. ACP communication also helps the clinician to better understand the context within which patients and their caregivers might make health care decisions, including their values and preferences for care. Patient-provider discussions about ACP focused on understanding patient values and initiated early in the trajectory of serious illness can support future in-the-moment decision-making, and is likely more effective than asking patients to make specific treatment decisions in advance [32]. A growing body of rigorous research has shown that ACP communication is associated with greater preference-concordant care and congruence in patient-surrogate understanding of patient preferences, lower costs, and less aggressive care at the end of life [33–37].

Patient Preferences for ACP Communication

Most patients with heart failure and their caregivers want honest disclosure regarding prognosis and to receive information about the expected trajectory of their disease [38–41] as early as possible [38] to help them plan and prepare for their future. Patients and their caregivers prefer to have these conversations with their physician [38] or other provider most familiar with the patient and family [39]. Patients also express a preference for support with dealing with the uncertainty inherent to heart failure [39]. Although most patients and caregivers desire to receive clear and honest communication about their disease, it is important to note that patients may vary in the extent of information they prefer to receive about their heart failure, with some individuals preferring not to talk about the end of life and future care needs at all [39,42–44].

Challenges to ACP Communication in Heart Failure

Despite patient and caregiver preferences for ACP communication with their providers, evidence suggests such communication occurs infrequently [40,45] and that heart failure patients may lack important information about their prognosis and treatment options [40,44,46,47]. For example, patients may not recognize the terminal nature of heart failure, and may be unaware of the range of treatment options, including hospice, available to them. Evidence also demonstrates that ACP is infrequently discussed with their health care providers [40], resulting in these conversations being avoided or deferred until an emergent clinical situation [44,48] when hasty questions about treatment choices may yield uncertain and conflicting answers not representative of a patient’s underlying values.

The infrequent, late, and often lack of discussions about ACP are driven by several challenges. First, the uncertain trajectory of heart failure makes communication regarding “what to expect” difficult. Prognostication is an immense challenge in heart failure [40,49–52], making it harder to talk about end-of-life issues and hindering the ability of patients, caregivers and health care providers to plan and prepare for the future. It is often difficult for clinicians, who face the challenge of instilling hope in the face of truthful disclosure [53], to identify the “right time” to initiate such discussions.

Second, a lack of time, particularly during outpatient visits, impedes physician ability to have considered discussions about future care needs and preferences [32,54]. The U.S. health care system currently lacks financial reimbursement for these discussions, which poses a significant barrier to the integration of ACP conversations into routine clinical practice. Moreover, these conversations are lengthy and iterative [53]. ACP discussions that are focused on facilitating patient-centered decision-making ideally begin with a discussion of expected prognosis, followed by an exploration of patient preferences and values for health care, and then a review of treatment options to be considered in the context of those preferences. Often additional time is needed for completing advance directive documents or for charting key outcomes from these discussions. Clinicians today are frequently overloaded with addressing multiple medical issues during outpatient visits that leave little time for non-medical tasks such as ACP discussions. The lack of financial incentives to support in-depth discussions is a critical challenge in improving ACP.

Third, a lack of training in specialized communication skills, particularly focused on empathic and emotionally sensitive disclosure, may further hinder physicians from initiating frank discussions with their patients. ACP conversations are highly sensitive and fraught with emotional complexity, and clinicians understandably experience discomfort with breaking bad news [49,51,55] or with broader issues of decline and death [51,56,57]. Physicians tend to be most comfortable addressing cognitive aspects of communication; addressing the emotional needs of patients is harder. Medical school training teaches detachment in physician practice, perhaps as a way of coping with the sadness they regularly confront and in maintaining their ability to provide clinical care. In fact, physicians describe their most difficult encounters as those with the most negative expressed emotions and miss opportunities to respond with empathy [58–60], a critical skill in effective patient-physician communication that is associated with improved patient satisfaction [61,62]. While patients value good communication skills in their health care encounters, many providers feel they lack the necessary skills to lead effective ACP discussions [49,63].

Finally, information gaps with regards to heart failure contribute to delayed or absent conversations about planning for future care. Many heart failure patients have a limited understanding of their disease [32,40,44,55], particularly an inaccurate perception that heart failure is not a terminal and life-limiting illness [42,49,64]. Compounding this is the fact that even some health care providers are reluctant to acknowledge the terminal nature of heart failure [50,56]. Without frank acknowledgement of the terminal nature of heart failure, the initiation of discussions regarding end-of-life care will remain difficult if not impossible.

Approaches to ACP in Heart Failure

When Is the Right Time?