User login

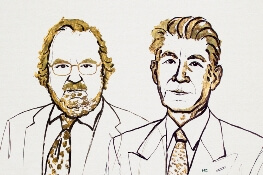

Two immunologists receive Nobel Prize in medicine

Two immunologists have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries that represent a “paradigmatic shift in the fight against cancer,” the Nobel committee said.

James P. Allison, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Tasuku Honjo, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University, shared the prize for their discovery of cancer therapies that work by inhibiting negative immune regulation.

Dr. Allison studied the protein CTLA-4 found on T cells, which acts as a T-cell brake, and Dr. Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells called PD-1 that also acts as a T-cell brake.

In addition to sharing the honor, the scientists will split the 9 million Swedish kronor ($1.01 million) that comes with the prize.

Drs. Allison and Honjo, working in parallel, pursued different strategies for inhibiting the brakes on the immune system. Both strategies produced effective checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cancer.

James P. Allison

Dr. Allison was one of several scientists during the 1990s who noticed that CTLA-4 functions as a brake on T cells. Unlike other scientists, however, he set out to investigate whether blocking CTLA-4 with an antibody he had already developed could release the brake on the immune system.

The antibody had “spectacular” effects in curing mice with cancer. Despite little interest from the pharmaceutical industry, Dr. Allison continued efforts to develop the antibody therapy for humans.

The antibody turned out to be ipilimumab, which was approved in 2011 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced melanoma.

Tasuko Honjo

A few years prior to Dr. Allison’s finding, Dr. Honjo discovered PD-1 and set out to determine its function. PD-1 also operates as a T-cell brake, but it uses a different mechanism than does CTLA-4.

Dr. Honjo and others demonstrated in animal experiments that PD-1 blockade could be an effective anticancer therapy. Over the years he demonstrated the efficacy of targeting PD-1 in different types of human cancers.

The first two PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab and nivolumab—were approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of melanoma.

Nivolumab is also approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer.

Pembrolizumab is also approved to treat primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, advanced NSCLC, classical HL, advanced gastric cancer, advanced cervical cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, advanced urothelial bladder cancer, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

And targeting both CTLA-4 and PD-1 in combination therapy together may prove to be even more effective in eliminating cancer cells than either strategy alone, as is being demonstrated in patients with melanoma.

The Nobel organization wrote in a press release, “Checkpoint therapy has now revolutionized cancer treatment and has fundamentally changed the way we view how cancer can be managed.”

Two immunologists have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries that represent a “paradigmatic shift in the fight against cancer,” the Nobel committee said.

James P. Allison, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Tasuku Honjo, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University, shared the prize for their discovery of cancer therapies that work by inhibiting negative immune regulation.

Dr. Allison studied the protein CTLA-4 found on T cells, which acts as a T-cell brake, and Dr. Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells called PD-1 that also acts as a T-cell brake.

In addition to sharing the honor, the scientists will split the 9 million Swedish kronor ($1.01 million) that comes with the prize.

Drs. Allison and Honjo, working in parallel, pursued different strategies for inhibiting the brakes on the immune system. Both strategies produced effective checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cancer.

James P. Allison

Dr. Allison was one of several scientists during the 1990s who noticed that CTLA-4 functions as a brake on T cells. Unlike other scientists, however, he set out to investigate whether blocking CTLA-4 with an antibody he had already developed could release the brake on the immune system.

The antibody had “spectacular” effects in curing mice with cancer. Despite little interest from the pharmaceutical industry, Dr. Allison continued efforts to develop the antibody therapy for humans.

The antibody turned out to be ipilimumab, which was approved in 2011 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced melanoma.

Tasuko Honjo

A few years prior to Dr. Allison’s finding, Dr. Honjo discovered PD-1 and set out to determine its function. PD-1 also operates as a T-cell brake, but it uses a different mechanism than does CTLA-4.

Dr. Honjo and others demonstrated in animal experiments that PD-1 blockade could be an effective anticancer therapy. Over the years he demonstrated the efficacy of targeting PD-1 in different types of human cancers.

The first two PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab and nivolumab—were approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of melanoma.

Nivolumab is also approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer.

Pembrolizumab is also approved to treat primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, advanced NSCLC, classical HL, advanced gastric cancer, advanced cervical cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, advanced urothelial bladder cancer, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

And targeting both CTLA-4 and PD-1 in combination therapy together may prove to be even more effective in eliminating cancer cells than either strategy alone, as is being demonstrated in patients with melanoma.

The Nobel organization wrote in a press release, “Checkpoint therapy has now revolutionized cancer treatment and has fundamentally changed the way we view how cancer can be managed.”

Two immunologists have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries that represent a “paradigmatic shift in the fight against cancer,” the Nobel committee said.

James P. Allison, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Tasuku Honjo, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University, shared the prize for their discovery of cancer therapies that work by inhibiting negative immune regulation.

Dr. Allison studied the protein CTLA-4 found on T cells, which acts as a T-cell brake, and Dr. Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells called PD-1 that also acts as a T-cell brake.

In addition to sharing the honor, the scientists will split the 9 million Swedish kronor ($1.01 million) that comes with the prize.

Drs. Allison and Honjo, working in parallel, pursued different strategies for inhibiting the brakes on the immune system. Both strategies produced effective checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of cancer.

James P. Allison

Dr. Allison was one of several scientists during the 1990s who noticed that CTLA-4 functions as a brake on T cells. Unlike other scientists, however, he set out to investigate whether blocking CTLA-4 with an antibody he had already developed could release the brake on the immune system.

The antibody had “spectacular” effects in curing mice with cancer. Despite little interest from the pharmaceutical industry, Dr. Allison continued efforts to develop the antibody therapy for humans.

The antibody turned out to be ipilimumab, which was approved in 2011 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced melanoma.

Tasuko Honjo

A few years prior to Dr. Allison’s finding, Dr. Honjo discovered PD-1 and set out to determine its function. PD-1 also operates as a T-cell brake, but it uses a different mechanism than does CTLA-4.

Dr. Honjo and others demonstrated in animal experiments that PD-1 blockade could be an effective anticancer therapy. Over the years he demonstrated the efficacy of targeting PD-1 in different types of human cancers.

The first two PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab and nivolumab—were approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of melanoma.

Nivolumab is also approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer.

Pembrolizumab is also approved to treat primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, advanced NSCLC, classical HL, advanced gastric cancer, advanced cervical cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, advanced urothelial bladder cancer, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

And targeting both CTLA-4 and PD-1 in combination therapy together may prove to be even more effective in eliminating cancer cells than either strategy alone, as is being demonstrated in patients with melanoma.

The Nobel organization wrote in a press release, “Checkpoint therapy has now revolutionized cancer treatment and has fundamentally changed the way we view how cancer can be managed.”

FDA lifts partial hold on tazemetostat trials

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor being developed to treat solid tumors and lymphomas, according to a press release from the drug’s developer Epizyme.

The patient had been on study for approximately 15 months and had achieved a confirmed partial response. The patient has since discontinued tazemetostat and responded to treatment for T-LBL.

“This remains the only case of T-LBL we’ve seen in more than 750 patients treated with tazemetostat,” Robert Bazemore, president and chief executive officer of Epizyme, said in a webcast on Sept. 24.

Epizyme assessed the risk of secondary malignancies, including T-LBL, as well as the overall risks and benefits of tazemetostat treatment, conducting a review of the published literature and an examination of efficacy and safety data across all of its tazemetostat trials. A panel of external scientific and medical experts who reviewed the findings concluded that T-LBL risks appear to be confined to pediatric patients who received higher doses of the drug. The phase 1 pediatric study in which the patient developed T-LBL included higher doses of tazemetostat than those used in the phase 2 adult studies.

“The team at Epizyme has worked diligently in collaboration with external experts and the FDA over the past several months,” Mr. Bazemore said.

The company is not making any substantial changes to trial designs or the patient populations involved in tazemetostat trials. However, Epizyme is modifying dosing in the pediatric studies, improving patient monitoring, and making changes to exclusion criteria to reduce the potential risk of T-LBL and other secondary malignancies. Mr. Bazemore said Epizyme hopes to submit a New Drug Application for tazemetostat in the treatment of epithelioid sarcoma.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy in phase 2 trials of follicular lymphoma and solid-tumor malignancies. The drug is also being studied as part of combination therapy for non–small cell lung cancer and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

In August, Epizyme announced its decision to stop developing tazemetostat for use as monotherapy or in combination with prednisolone for patients with DLBCL. However, tazemetostat is still under investigation as a potential treatment for DLBCL as part of other combination regimens.

Epizyme is now working to resolve partial clinical holds placed on tazemetostat in France and Germany in order to resume trial enrollment in those countries.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor being developed to treat solid tumors and lymphomas, according to a press release from the drug’s developer Epizyme.

The patient had been on study for approximately 15 months and had achieved a confirmed partial response. The patient has since discontinued tazemetostat and responded to treatment for T-LBL.

“This remains the only case of T-LBL we’ve seen in more than 750 patients treated with tazemetostat,” Robert Bazemore, president and chief executive officer of Epizyme, said in a webcast on Sept. 24.

Epizyme assessed the risk of secondary malignancies, including T-LBL, as well as the overall risks and benefits of tazemetostat treatment, conducting a review of the published literature and an examination of efficacy and safety data across all of its tazemetostat trials. A panel of external scientific and medical experts who reviewed the findings concluded that T-LBL risks appear to be confined to pediatric patients who received higher doses of the drug. The phase 1 pediatric study in which the patient developed T-LBL included higher doses of tazemetostat than those used in the phase 2 adult studies.

“The team at Epizyme has worked diligently in collaboration with external experts and the FDA over the past several months,” Mr. Bazemore said.

The company is not making any substantial changes to trial designs or the patient populations involved in tazemetostat trials. However, Epizyme is modifying dosing in the pediatric studies, improving patient monitoring, and making changes to exclusion criteria to reduce the potential risk of T-LBL and other secondary malignancies. Mr. Bazemore said Epizyme hopes to submit a New Drug Application for tazemetostat in the treatment of epithelioid sarcoma.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy in phase 2 trials of follicular lymphoma and solid-tumor malignancies. The drug is also being studied as part of combination therapy for non–small cell lung cancer and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

In August, Epizyme announced its decision to stop developing tazemetostat for use as monotherapy or in combination with prednisolone for patients with DLBCL. However, tazemetostat is still under investigation as a potential treatment for DLBCL as part of other combination regimens.

Epizyme is now working to resolve partial clinical holds placed on tazemetostat in France and Germany in order to resume trial enrollment in those countries.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor being developed to treat solid tumors and lymphomas, according to a press release from the drug’s developer Epizyme.

The patient had been on study for approximately 15 months and had achieved a confirmed partial response. The patient has since discontinued tazemetostat and responded to treatment for T-LBL.

“This remains the only case of T-LBL we’ve seen in more than 750 patients treated with tazemetostat,” Robert Bazemore, president and chief executive officer of Epizyme, said in a webcast on Sept. 24.

Epizyme assessed the risk of secondary malignancies, including T-LBL, as well as the overall risks and benefits of tazemetostat treatment, conducting a review of the published literature and an examination of efficacy and safety data across all of its tazemetostat trials. A panel of external scientific and medical experts who reviewed the findings concluded that T-LBL risks appear to be confined to pediatric patients who received higher doses of the drug. The phase 1 pediatric study in which the patient developed T-LBL included higher doses of tazemetostat than those used in the phase 2 adult studies.

“The team at Epizyme has worked diligently in collaboration with external experts and the FDA over the past several months,” Mr. Bazemore said.

The company is not making any substantial changes to trial designs or the patient populations involved in tazemetostat trials. However, Epizyme is modifying dosing in the pediatric studies, improving patient monitoring, and making changes to exclusion criteria to reduce the potential risk of T-LBL and other secondary malignancies. Mr. Bazemore said Epizyme hopes to submit a New Drug Application for tazemetostat in the treatment of epithelioid sarcoma.

Tazemetostat is under investigation as monotherapy in phase 2 trials of follicular lymphoma and solid-tumor malignancies. The drug is also being studied as part of combination therapy for non–small cell lung cancer and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

In August, Epizyme announced its decision to stop developing tazemetostat for use as monotherapy or in combination with prednisolone for patients with DLBCL. However, tazemetostat is still under investigation as a potential treatment for DLBCL as part of other combination regimens.

Epizyme is now working to resolve partial clinical holds placed on tazemetostat in France and Germany in order to resume trial enrollment in those countries.

FDA Approves Galcanezumab for Migraine Prevention

The treatment is the third anti-CGRP antibody to receive regulatory approval.

ROCKVILLE, MD—The FDA has approved galcanezumab-gnlm (Emgality) for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Eli Lilly and Company manufactures the therapy. Emgality is the third calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist to receive regulatory approval.

The approval is based on the results of three phase III clinical trials: EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN. EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2 were six-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included adults with episodic migraine. REGAIN was a three-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with chronic migraine. The primary end point of all three trials was mean change from baseline in the number of monthly headache days.

In all trials, patients received either placebo, 120 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm after an initial loading dose of 240 mg, or 240 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm. In EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2, people who received galcanezumab-gnlm had significantly fewer headache days per month than people who received placebo, and those who received galcanezumab-gnlm were also more likely to achieve a 50%, 75%, and 100% reduction in headache days.

In REGAIN, patients who received galcanezumab-gnlm experienced fewer monthly headache days than those who received placebo and were more likely to achieve a 50% reduction in headache days. There was no difference between groups in the likelihood of achieving a 75% or 100% reduction.

The recommended dosage, according to the label, is a monthly, 120-mg subcutaneous injection with an initial loading dose of 240 mg. The most common adverse event associated with galcanezumab-gnlm is injection-site reaction.

Galcanezumab-gnlm is under final review by the European Commission for approval in Europe.

—Lucas Franki

The treatment is the third anti-CGRP antibody to receive regulatory approval.

The treatment is the third anti-CGRP antibody to receive regulatory approval.

ROCKVILLE, MD—The FDA has approved galcanezumab-gnlm (Emgality) for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Eli Lilly and Company manufactures the therapy. Emgality is the third calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist to receive regulatory approval.

The approval is based on the results of three phase III clinical trials: EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN. EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2 were six-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included adults with episodic migraine. REGAIN was a three-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with chronic migraine. The primary end point of all three trials was mean change from baseline in the number of monthly headache days.

In all trials, patients received either placebo, 120 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm after an initial loading dose of 240 mg, or 240 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm. In EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2, people who received galcanezumab-gnlm had significantly fewer headache days per month than people who received placebo, and those who received galcanezumab-gnlm were also more likely to achieve a 50%, 75%, and 100% reduction in headache days.

In REGAIN, patients who received galcanezumab-gnlm experienced fewer monthly headache days than those who received placebo and were more likely to achieve a 50% reduction in headache days. There was no difference between groups in the likelihood of achieving a 75% or 100% reduction.

The recommended dosage, according to the label, is a monthly, 120-mg subcutaneous injection with an initial loading dose of 240 mg. The most common adverse event associated with galcanezumab-gnlm is injection-site reaction.

Galcanezumab-gnlm is under final review by the European Commission for approval in Europe.

—Lucas Franki

ROCKVILLE, MD—The FDA has approved galcanezumab-gnlm (Emgality) for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Eli Lilly and Company manufactures the therapy. Emgality is the third calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonist to receive regulatory approval.

The approval is based on the results of three phase III clinical trials: EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN. EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2 were six-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included adults with episodic migraine. REGAIN was a three-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with chronic migraine. The primary end point of all three trials was mean change from baseline in the number of monthly headache days.

In all trials, patients received either placebo, 120 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm after an initial loading dose of 240 mg, or 240 mg of galcanezumab-gnlm. In EVOLVE-1 and EVOLVE-2, people who received galcanezumab-gnlm had significantly fewer headache days per month than people who received placebo, and those who received galcanezumab-gnlm were also more likely to achieve a 50%, 75%, and 100% reduction in headache days.

In REGAIN, patients who received galcanezumab-gnlm experienced fewer monthly headache days than those who received placebo and were more likely to achieve a 50% reduction in headache days. There was no difference between groups in the likelihood of achieving a 75% or 100% reduction.

The recommended dosage, according to the label, is a monthly, 120-mg subcutaneous injection with an initial loading dose of 240 mg. The most common adverse event associated with galcanezumab-gnlm is injection-site reaction.

Galcanezumab-gnlm is under final review by the European Commission for approval in Europe.

—Lucas Franki

New MS Subtype Shows Absence of Cerebral White Matter Demyelination

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis (MS) called myelocortical MS is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter, according to a study published online ahead of print August 21 in Lancet Neurology. The findings are based on an examination of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of MS.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, the Morris R. and Ruth V. Graham Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research at the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors said that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of MS, previous research has found that only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they said.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as myelocortical MS, characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals with 12 individuals with typical MS matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, MS disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale score.

Not Typical MS

They found that while individuals with myelocortical MS did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex similar to those of individuals with typical MS (median 4.45% vs 9.74%, respectively). However, the individuals with myelocortical MS had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs 13.81%).

Individuals with myelocortical MS also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains, in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical MS only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Dr. Trapp and colleagues also saw that in typical MS, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical MS.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical MS, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted, and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images. They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical MS and those with typical MS, although individuals with typical MS had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

The Hallmarks of Myelocortical MS

“We propose that myelocortical MS is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” Dr. Trapp and colleagues wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathologic evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical MS.”

The authors acknowledged that one limitation of their study may have been selection bias, as all the patients in the study died from complications of advanced MS. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical MS seen in their sample would be similar across the entire MS population, nor were the findings likely to apply to pateints with earlier stage disease.

The study received funding from the NIH and the National MS Society. One author is an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors are employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and nonfinancial support from pharmaceutical companies.

—Bianca Nogrady

Suggested Reading

Trapp BD, Vignos M, Dudman J, et al. Cortical neuronal densities and cerebral white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21 [Epub ahead of print].

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis (MS) called myelocortical MS is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter, according to a study published online ahead of print August 21 in Lancet Neurology. The findings are based on an examination of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of MS.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, the Morris R. and Ruth V. Graham Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research at the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors said that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of MS, previous research has found that only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they said.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as myelocortical MS, characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals with 12 individuals with typical MS matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, MS disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale score.

Not Typical MS

They found that while individuals with myelocortical MS did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex similar to those of individuals with typical MS (median 4.45% vs 9.74%, respectively). However, the individuals with myelocortical MS had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs 13.81%).

Individuals with myelocortical MS also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains, in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical MS only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Dr. Trapp and colleagues also saw that in typical MS, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical MS.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical MS, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted, and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images. They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical MS and those with typical MS, although individuals with typical MS had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

The Hallmarks of Myelocortical MS

“We propose that myelocortical MS is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” Dr. Trapp and colleagues wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathologic evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical MS.”

The authors acknowledged that one limitation of their study may have been selection bias, as all the patients in the study died from complications of advanced MS. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical MS seen in their sample would be similar across the entire MS population, nor were the findings likely to apply to pateints with earlier stage disease.

The study received funding from the NIH and the National MS Society. One author is an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors are employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and nonfinancial support from pharmaceutical companies.

—Bianca Nogrady

Suggested Reading

Trapp BD, Vignos M, Dudman J, et al. Cortical neuronal densities and cerebral white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21 [Epub ahead of print].

A new subtype of multiple sclerosis (MS) called myelocortical MS is characterized by demyelination only in the spinal cord and cerebral cortex and not in the cerebral white matter, according to a study published online ahead of print August 21 in Lancet Neurology. The findings are based on an examination of the brains and spinal cords of 100 patients who died of MS.

Bruce D. Trapp, PhD, the Morris R. and Ruth V. Graham Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research at the Lerner Research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and his coauthors said that while the demyelination of cerebral white matter is a pathologic hallmark of MS, previous research has found that only around half of cerebral T2-weighted hyperintense white matter lesions are demyelinated, and these lesions account for less than a third of variance in the rate of brain atrophy.

“In the absence of specific MRI metrics for demyelination, the relationship between cerebral white-matter demyelination and neurodegeneration remains speculative,” they said.

In this study, researchers scanned the brains with MRI before autopsy, then took centimeter-thick hemispheric slices to study the white-matter lesions. They identified 12 individuals as having what they describe as myelocortical MS, characterized by the absence of areas of cerebral white-matter discoloration indicative of demyelinated lesions.

The authors then compared these individuals with 12 individuals with typical MS matched by age, sex, MRI protocol, MS disease subtype, disease duration, and Expanded Disability Status Scale score.

Not Typical MS

They found that while individuals with myelocortical MS did not have demyelinated lesions in the cerebral white matter, they had areas of demyelinated lesions in the cerebral cortex similar to those of individuals with typical MS (median 4.45% vs 9.74%, respectively). However, the individuals with myelocortical MS had a significantly smaller area of spinal cord demyelination (median 3.81% vs 13.81%).

Individuals with myelocortical MS also had significantly lower mean cortical neuronal densities, compared with healthy control brains, in layer III, layer V, and layer VI. But individuals with typical MS only had a lower cortical neuronal density in layer V when compared with controls.

Dr. Trapp and colleagues also saw that in typical MS, neuronal density decreased as the area of brain white-matter demyelination increased. However, this negative linear correlation was not seen in myelocortical MS.

On MRI, researchers were still able to see abnormalities in the cerebral white matter in individuals with myelocortical MS, in T2-weighted, T1-weighted, and magnetization transfer ratios (MTR) images. They also found similar total T2-weighted and T1-weighted lesion volumes in individuals with myelocortical MS and those with typical MS, although individuals with typical MS had significantly greater MTR lesion volumes.

The Hallmarks of Myelocortical MS

“We propose that myelocortical MS is characterized by spinal cord demyelination, subpial cortical demyelination, and an absence of cerebral white-matter demyelination,” Dr. Trapp and colleagues wrote. “Our findings indicate that abnormal cerebral white-matter T2-T1-MTR regions of interest are not always demyelinated, and this pathologic evidence suggests that cerebral white-matter demyelination and cortical neuronal degeneration can be independent events in myelocortical MS.”

The authors acknowledged that one limitation of their study may have been selection bias, as all the patients in the study died from complications of advanced MS. They suggested that it was therefore not appropriate to conclude that the prevalence of myelocortical MS seen in their sample would be similar across the entire MS population, nor were the findings likely to apply to pateints with earlier stage disease.

The study received funding from the NIH and the National MS Society. One author is an employee of Renovo Neural, and three authors are employees of Biogen. One author declared a pending patent related to automated lesion segmentation from MRI images, and four authors declared funding, fees, and nonfinancial support from pharmaceutical companies.

—Bianca Nogrady

Suggested Reading

Trapp BD, Vignos M, Dudman J, et al. Cortical neuronal densities and cerebral white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Aug 21 [Epub ahead of print].

Cardiovascular Health and Cognitive Decline: What Is the Connection?

Maintaining cardiovascular health may reduce white matter hyperintensities and decrease the risk of dementia.

Optimal measures of cardiovascular health are associated with brain health in adults, according to two studies published in the August 21 issue of JAMA.

In a French population-based cohort study, adults ages 65 and older with more cardiovascular health measures at ideal levels had a lower risk of dementia and lower rates of cognitive decline than did those with fewer optimal cardiovascular measures, such as blood pressure and physical activity.

In addition, a preliminary, cross-sectional study of younger adults found that the number of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels was associated with brain vessel structure and function and the number of white matter hyperintensities.

“These two studies convey an immediately actionable message to clinicians, policy makers, and patients,” said Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, and Mary Cushman, MD, in an accompanying editorial. “Available evidence indicates that to achieve a lifetime of robust brain health free of dementia, it is never too early or too late to strive for attainment of ideal cardiovascular health.” Dr. Saver is a Professor of Neurology and Director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Cushman is a Professor of Medicine and Pathology at Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont in Burlington.

Cardiovascular Health in Older Age

Vascular dementia is the second most common neuropathologic basis of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease, and “most cases of dementia arise from a combination of [Alzheimer’s disease] and cerebrovascular pathology,” the editorialists noted. Studies have suggested a connection between cardiovascular health and dementia, but the evidence is limited.

Cécilia Samieri, PhD, a Senior Researcher at the Bordeaux Population Health Research Center at the Université de Bordeaux in France, and colleagues studied people age 65 and older from Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier, France, to examine the association between cardiovascular health level and risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults.

The study included 6,626 people without a history of cardiovascular disease or dementia at baseline. Participants underwent in-person neuropsychologic testing between January 1999 and July 2016 and systematic detection of incident dementia. Participants had a mean age of 73.7, and 63.4% were women.

The investigators defined cardiovascular health using a seven-item tool from the American Heart Association (AHA). They determined the number of the AHA’s Life’s Simple Seven metrics that were at recommended levels (ie, nonsmoking, BMI < 25, regular physical activity, eating fish at least twice per week and fruits and vegetables at least three times per day, cholesterol < 200 mg/dL [untreated], fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL [untreated], and blood pressure < 120/80 mm Hg [untreated]).

Approximately 36.5% of the cohort had zero, one, or two optimal health metrics, 57.1% had three or four optimal health metrics, and 6.5% had five, six, or seven optimal health metrics.

During an average follow-up of 8.5 years, 745 participants developed dementia. Among participants with zero or one health metrics at optimal levels at baseline, the incidence rate of dementia was 1.76 per 100 person-years. Compared with this rate, the incidence rate per 100 person-years was 0.26 lower for participants with two optimal health metrics, 0.59 lower for participants with three optimal health metrics, 0.43 lower for participants with four optimal health metrics, 0.93 lower for participants with five optimal health metrics, and 0.96 lower for participants with six or seven optimal health metrics.

“In multivariable models, the hazard ratios for dementia were 0.90 per additional optimal metric,” the investigators said. “The study results support the recent recommendations of the AHA and the American Stroke Association for the promotion of the Life’s Simple Seven tool.”

Cerebrovascular Structure and Function in Young Adults

Wilby Williamson, BMBS

The researchers assessed patients’ cerebral vessel density, caliber, and tortuosity and brain white matter hyperintensity lesion count. In a subgroup of 52 participants, they assessed cerebral blood flow.

The researchers determined for each participant how many of eight modifiable risk factors were at recommended levels (ie, BMI < 25, highest tertile of cardiovascular fitness or physical activity, alcohol consumption < eight drinks per week, nonsmoker for more than six months, blood pressure on awake ambulatory monitoring < 130/80 mm Hg, a nonhypertensive diastolic response to exercise [ie, peak diastolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg], total cholesterol < 200 mg/dL, and fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL).

On average, participants had six of the eight modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels.

In multivariable models, cardiovascular risk factors were associated with cerebrovascular structure and the number of white matter hyperintensities. “For each additional modifiable risk factor categorized as healthy, vessel density was greater by 0.3 vessels/cm3, vessel caliber was greater by 8 μm, and white matter hyperintensity lesions were fewer by 1.6 lesions. Among the 52 participants with available data, cerebral blood flow varied with vessel density and was 2.5 mL/100 g/min higher for each healthier category of a modifiable risk factor,” Dr. Williamson and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “some individuals may be starting to diverge to different risk trajectories for brain vascular health in early adulthood,” the researchers said. The study was exploratory, however, and follow-up studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of these findings, they said.

“The magnitude of changes was generally much less than would be expected to produce clinical symptoms such as cognitive impairment or gait difficulty,” said Drs. Saver and Cushman. The changes, however, “may portend more substantial abnormalities later in life,” they said. “Even during the late-life period, when septuagenarians become octogenarians, cardiovascular health is associated with substantial differences in cognitive trajectory and dementia onset.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Samieri C, Perier MC, Gaye B, et al. Association of cardiovascular health level in older age with cognitive decline and incident dementia. JAMA. 2018;320(7):657-664.

Saver JL, Cushman M. Striving for ideal cardiovascular and brain health: It is never too early or too late. JAMA. 2018; 320(7):645-647.

Williamson W, Lewandowski AJ, Forkert ND, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with MRI indices of cerebrovascular structure and function and white matter hyperintensities in young adults. JAMA. 2018;320(7):665-673.

Maintaining cardiovascular health may reduce white matter hyperintensities and decrease the risk of dementia.

Maintaining cardiovascular health may reduce white matter hyperintensities and decrease the risk of dementia.

Optimal measures of cardiovascular health are associated with brain health in adults, according to two studies published in the August 21 issue of JAMA.

In a French population-based cohort study, adults ages 65 and older with more cardiovascular health measures at ideal levels had a lower risk of dementia and lower rates of cognitive decline than did those with fewer optimal cardiovascular measures, such as blood pressure and physical activity.

In addition, a preliminary, cross-sectional study of younger adults found that the number of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels was associated with brain vessel structure and function and the number of white matter hyperintensities.

“These two studies convey an immediately actionable message to clinicians, policy makers, and patients,” said Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, and Mary Cushman, MD, in an accompanying editorial. “Available evidence indicates that to achieve a lifetime of robust brain health free of dementia, it is never too early or too late to strive for attainment of ideal cardiovascular health.” Dr. Saver is a Professor of Neurology and Director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Cushman is a Professor of Medicine and Pathology at Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont in Burlington.

Cardiovascular Health in Older Age

Vascular dementia is the second most common neuropathologic basis of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease, and “most cases of dementia arise from a combination of [Alzheimer’s disease] and cerebrovascular pathology,” the editorialists noted. Studies have suggested a connection between cardiovascular health and dementia, but the evidence is limited.

Cécilia Samieri, PhD, a Senior Researcher at the Bordeaux Population Health Research Center at the Université de Bordeaux in France, and colleagues studied people age 65 and older from Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier, France, to examine the association between cardiovascular health level and risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults.

The study included 6,626 people without a history of cardiovascular disease or dementia at baseline. Participants underwent in-person neuropsychologic testing between January 1999 and July 2016 and systematic detection of incident dementia. Participants had a mean age of 73.7, and 63.4% were women.

The investigators defined cardiovascular health using a seven-item tool from the American Heart Association (AHA). They determined the number of the AHA’s Life’s Simple Seven metrics that were at recommended levels (ie, nonsmoking, BMI < 25, regular physical activity, eating fish at least twice per week and fruits and vegetables at least three times per day, cholesterol < 200 mg/dL [untreated], fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL [untreated], and blood pressure < 120/80 mm Hg [untreated]).

Approximately 36.5% of the cohort had zero, one, or two optimal health metrics, 57.1% had three or four optimal health metrics, and 6.5% had five, six, or seven optimal health metrics.

During an average follow-up of 8.5 years, 745 participants developed dementia. Among participants with zero or one health metrics at optimal levels at baseline, the incidence rate of dementia was 1.76 per 100 person-years. Compared with this rate, the incidence rate per 100 person-years was 0.26 lower for participants with two optimal health metrics, 0.59 lower for participants with three optimal health metrics, 0.43 lower for participants with four optimal health metrics, 0.93 lower for participants with five optimal health metrics, and 0.96 lower for participants with six or seven optimal health metrics.

“In multivariable models, the hazard ratios for dementia were 0.90 per additional optimal metric,” the investigators said. “The study results support the recent recommendations of the AHA and the American Stroke Association for the promotion of the Life’s Simple Seven tool.”

Cerebrovascular Structure and Function in Young Adults

Wilby Williamson, BMBS

The researchers assessed patients’ cerebral vessel density, caliber, and tortuosity and brain white matter hyperintensity lesion count. In a subgroup of 52 participants, they assessed cerebral blood flow.

The researchers determined for each participant how many of eight modifiable risk factors were at recommended levels (ie, BMI < 25, highest tertile of cardiovascular fitness or physical activity, alcohol consumption < eight drinks per week, nonsmoker for more than six months, blood pressure on awake ambulatory monitoring < 130/80 mm Hg, a nonhypertensive diastolic response to exercise [ie, peak diastolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg], total cholesterol < 200 mg/dL, and fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL).

On average, participants had six of the eight modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels.

In multivariable models, cardiovascular risk factors were associated with cerebrovascular structure and the number of white matter hyperintensities. “For each additional modifiable risk factor categorized as healthy, vessel density was greater by 0.3 vessels/cm3, vessel caliber was greater by 8 μm, and white matter hyperintensity lesions were fewer by 1.6 lesions. Among the 52 participants with available data, cerebral blood flow varied with vessel density and was 2.5 mL/100 g/min higher for each healthier category of a modifiable risk factor,” Dr. Williamson and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “some individuals may be starting to diverge to different risk trajectories for brain vascular health in early adulthood,” the researchers said. The study was exploratory, however, and follow-up studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of these findings, they said.

“The magnitude of changes was generally much less than would be expected to produce clinical symptoms such as cognitive impairment or gait difficulty,” said Drs. Saver and Cushman. The changes, however, “may portend more substantial abnormalities later in life,” they said. “Even during the late-life period, when septuagenarians become octogenarians, cardiovascular health is associated with substantial differences in cognitive trajectory and dementia onset.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Samieri C, Perier MC, Gaye B, et al. Association of cardiovascular health level in older age with cognitive decline and incident dementia. JAMA. 2018;320(7):657-664.

Saver JL, Cushman M. Striving for ideal cardiovascular and brain health: It is never too early or too late. JAMA. 2018; 320(7):645-647.

Williamson W, Lewandowski AJ, Forkert ND, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with MRI indices of cerebrovascular structure and function and white matter hyperintensities in young adults. JAMA. 2018;320(7):665-673.

Optimal measures of cardiovascular health are associated with brain health in adults, according to two studies published in the August 21 issue of JAMA.

In a French population-based cohort study, adults ages 65 and older with more cardiovascular health measures at ideal levels had a lower risk of dementia and lower rates of cognitive decline than did those with fewer optimal cardiovascular measures, such as blood pressure and physical activity.

In addition, a preliminary, cross-sectional study of younger adults found that the number of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels was associated with brain vessel structure and function and the number of white matter hyperintensities.

“These two studies convey an immediately actionable message to clinicians, policy makers, and patients,” said Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, and Mary Cushman, MD, in an accompanying editorial. “Available evidence indicates that to achieve a lifetime of robust brain health free of dementia, it is never too early or too late to strive for attainment of ideal cardiovascular health.” Dr. Saver is a Professor of Neurology and Director of the Stroke Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Cushman is a Professor of Medicine and Pathology at Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont in Burlington.

Cardiovascular Health in Older Age

Vascular dementia is the second most common neuropathologic basis of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease, and “most cases of dementia arise from a combination of [Alzheimer’s disease] and cerebrovascular pathology,” the editorialists noted. Studies have suggested a connection between cardiovascular health and dementia, but the evidence is limited.

Cécilia Samieri, PhD, a Senior Researcher at the Bordeaux Population Health Research Center at the Université de Bordeaux in France, and colleagues studied people age 65 and older from Bordeaux, Dijon, and Montpellier, France, to examine the association between cardiovascular health level and risk of dementia and cognitive decline in older adults.

The study included 6,626 people without a history of cardiovascular disease or dementia at baseline. Participants underwent in-person neuropsychologic testing between January 1999 and July 2016 and systematic detection of incident dementia. Participants had a mean age of 73.7, and 63.4% were women.

The investigators defined cardiovascular health using a seven-item tool from the American Heart Association (AHA). They determined the number of the AHA’s Life’s Simple Seven metrics that were at recommended levels (ie, nonsmoking, BMI < 25, regular physical activity, eating fish at least twice per week and fruits and vegetables at least three times per day, cholesterol < 200 mg/dL [untreated], fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL [untreated], and blood pressure < 120/80 mm Hg [untreated]).

Approximately 36.5% of the cohort had zero, one, or two optimal health metrics, 57.1% had three or four optimal health metrics, and 6.5% had five, six, or seven optimal health metrics.

During an average follow-up of 8.5 years, 745 participants developed dementia. Among participants with zero or one health metrics at optimal levels at baseline, the incidence rate of dementia was 1.76 per 100 person-years. Compared with this rate, the incidence rate per 100 person-years was 0.26 lower for participants with two optimal health metrics, 0.59 lower for participants with three optimal health metrics, 0.43 lower for participants with four optimal health metrics, 0.93 lower for participants with five optimal health metrics, and 0.96 lower for participants with six or seven optimal health metrics.

“In multivariable models, the hazard ratios for dementia were 0.90 per additional optimal metric,” the investigators said. “The study results support the recent recommendations of the AHA and the American Stroke Association for the promotion of the Life’s Simple Seven tool.”

Cerebrovascular Structure and Function in Young Adults

Wilby Williamson, BMBS

The researchers assessed patients’ cerebral vessel density, caliber, and tortuosity and brain white matter hyperintensity lesion count. In a subgroup of 52 participants, they assessed cerebral blood flow.

The researchers determined for each participant how many of eight modifiable risk factors were at recommended levels (ie, BMI < 25, highest tertile of cardiovascular fitness or physical activity, alcohol consumption < eight drinks per week, nonsmoker for more than six months, blood pressure on awake ambulatory monitoring < 130/80 mm Hg, a nonhypertensive diastolic response to exercise [ie, peak diastolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg], total cholesterol < 200 mg/dL, and fasting glucose < 100 mg/dL).

On average, participants had six of the eight modifiable cardiovascular risk factors at recommended levels.

In multivariable models, cardiovascular risk factors were associated with cerebrovascular structure and the number of white matter hyperintensities. “For each additional modifiable risk factor categorized as healthy, vessel density was greater by 0.3 vessels/cm3, vessel caliber was greater by 8 μm, and white matter hyperintensity lesions were fewer by 1.6 lesions. Among the 52 participants with available data, cerebral blood flow varied with vessel density and was 2.5 mL/100 g/min higher for each healthier category of a modifiable risk factor,” Dr. Williamson and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “some individuals may be starting to diverge to different risk trajectories for brain vascular health in early adulthood,” the researchers said. The study was exploratory, however, and follow-up studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of these findings, they said.

“The magnitude of changes was generally much less than would be expected to produce clinical symptoms such as cognitive impairment or gait difficulty,” said Drs. Saver and Cushman. The changes, however, “may portend more substantial abnormalities later in life,” they said. “Even during the late-life period, when septuagenarians become octogenarians, cardiovascular health is associated with substantial differences in cognitive trajectory and dementia onset.”

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Samieri C, Perier MC, Gaye B, et al. Association of cardiovascular health level in older age with cognitive decline and incident dementia. JAMA. 2018;320(7):657-664.

Saver JL, Cushman M. Striving for ideal cardiovascular and brain health: It is never too early or too late. JAMA. 2018; 320(7):645-647.

Williamson W, Lewandowski AJ, Forkert ND, et al. Association of cardiovascular risk factors with MRI indices of cerebrovascular structure and function and white matter hyperintensities in young adults. JAMA. 2018;320(7):665-673.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD, on Medication Overuse Headache

Neurology Reviews recently shared two poll questions with our Facebook followers about treatment medication overuse headache (MOH). I was very interested to see the results of our poll. While the number of responses was somewhat low, we do get some sense of what respondents are saying. In this commentary, I will first tell you my perspective on the answers and then we will see what some other headache specialists say about the answers to these questions.

Poll Results:

Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?

33 votes

YES, 39%

NO, 61%

Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor) without detoxification?

26 votes

YES, 38%

NO, 62%

My Commentary:

Let me explain in more detail my thoughts on the first question, “Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?”

If a patient had the diagnosis of MOH – meaning 15 or more headache days per month for at least 3 months, with use of stronger medications (triptans, ergots, opiates, butalbital-containing medications) for 10 days per month or milder treatment (aspirin, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) for 15 days per month – can they improve by being put on a traditional preventive medication without intentionally reducing their overused acute medications by a detoxification protocol ordered by a doctor or nurse?

Only 39% of our audience said yes. Yet some studies have shown that patients placed on onabotulinumtoxinA or topiramate might improve without them going through a detoxification of the overused medications. As a physician, I would suggest simultaneously decreasing in their acute medications. I think in some cases this approach creates additional improvement and makes the patient feel better. It would be better for their quality of life, as well as for their kidneys and possibly even their brains.

Here are my thoughts on the second question, “Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor), without detoxification?”

If a patient has MOH, can you expect them to improve after being placed on 1 of the 4 monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or its receptor – all of which are either recently approved or currently in development – without suggesting that they decrease their overused acute care medications? Note that erenumab (Aimovig-aaoe) has been approved by the FDA and marketed as of the time of this writing; we expect 2 more products to be approved very soon.

Almost an identical percentage of our audience (38%) said yes. There is evidence in published clinical trials that those patients given these new medications did about as well with or without the presence of MOH, and both groups did better than the placebo patients. Note that most trials prohibited overuse of opiates and butalbital.

I am a firm believer of detoxifying patients from their overused over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications. I believe that opiates and butalbital-containing medications, when overused, are worse for patients than OTCs, NSAIDs, ergot and triptans, but all of these can cause MOH. There are many studies showing that both inpatient and outpatient detoxification alone can really help. However, it is difficult to detoxify patients and some refuse to try this approach.

So, what should we do as physicians? If a patient has MOH, I educate them, try to detoxify them slowly on an outpatient basis, and if I feel it will help, start them on a preventive medication, even before the detoxification begins so they can reach therapeutic levels. In the future, will I use one of the standard preventives, approved or off-label, for migraine prevention (beta blockers, topiramate and other anticonvulsants, antidepressants, angiotensin receptor blockers, onabotulinumtoxinA and others)? It remains to be seen. I am leaning towards the anti CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies and preventive small molecule oral CGRP receptor blockers. While that might be enough to start with, I will continue explaining to my patients why they should actively begin a slow detoxification.

Let us see what some headache specialists said about both questions.

Robert Cowan, MD, FAAN:

There have been studies that show migraine can improve without the discontinuation of medication overuse. But that is not what the question asks. The question as posed is whether MOH can be treated with a preventive medication without detoxification. Since the diagnosis of MOH has, in the past, required the cessation of overuse leading to an improvement in the underlying headache, then technically, the answer would be “no.” But that being said, there is ample evidence that the number of headache days/months and other measures of headache can, in fact, improve with the introduction of a preventive, along with other measures such as lifestyle modification. The other ambiguity in the question has to do with what is meant by “detoxification.” Is this a hospital-based detox, or is a gradual decrease in the offending medicine in combination with the addition of a preventive, still considered “detoxification?” Also, does the response imply a sequential relationship between the detoxification and initiation of the preventive? Without further clarification, this response ratio to the question is very difficult to interpret.

There is animal data that suggests acute migraine medications may promote MOH in susceptible individuals through CGRP-dependent mechanisms and anti-CGRP antibodies may be useful for the MOH (Cephalalgia. 2017;37(6):560-570. doi: 10.1177/0333102416650702). While there are no published CGRP antibody studies that did not exclude MOH patients to my knowledge, an abstract by Silberstein et al at the recent AHS Scientific Meeting reported decreased use of overused medication with fremanazumab (Headache. 2018;58(S2):76-78).

Ira Turner, MD

There is clear data to suggest that it is not necessary to detoxify these patients before starting preventive therapy. This is true for the older and newer medications. In fact, not only do these preventive therapies still work in the presence of medication overuse, but they also help to reduce medication overuse. The one caveat that must be mentioned is that this may not apply to opiate overuse. Opiate over-users were excluded from these studies.

While it is of course our goal to reduce and stop acute medication overuse, it should not be done at the expense of delaying preventive therapy. In fact, it is desirable to do both simultaneously. This applies to oral preventive medications, botulinum toxin and CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

In view of this well-established data, it was quite surprising to me to see the results of the 2 polls cited. It seems as if we still have a lot of educating to do regarding migraine prevention in general and with medication overuse in migraine in particular.

Stewart Tepper, MD

Dr. Tepper did not have time to comment, but suggested we show you an abstract presented at the recent AHS meeting. It shows that erenumab-aaoe helps patients with MOH who have not been detoxified (Headache. 2018;58(S2):160-162).

###

Please write to us at Neurology Reviews Migraine Resource Center ([email protected]) with your opinions.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Migraine Resource Center

Clinical Professor of Neurology

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Los Angeles, California

Neurology Reviews recently shared two poll questions with our Facebook followers about treatment medication overuse headache (MOH). I was very interested to see the results of our poll. While the number of responses was somewhat low, we do get some sense of what respondents are saying. In this commentary, I will first tell you my perspective on the answers and then we will see what some other headache specialists say about the answers to these questions.

Poll Results:

Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?

33 votes

YES, 39%

NO, 61%

Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor) without detoxification?

26 votes

YES, 38%

NO, 62%

My Commentary:

Let me explain in more detail my thoughts on the first question, “Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?”

If a patient had the diagnosis of MOH – meaning 15 or more headache days per month for at least 3 months, with use of stronger medications (triptans, ergots, opiates, butalbital-containing medications) for 10 days per month or milder treatment (aspirin, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) for 15 days per month – can they improve by being put on a traditional preventive medication without intentionally reducing their overused acute medications by a detoxification protocol ordered by a doctor or nurse?

Only 39% of our audience said yes. Yet some studies have shown that patients placed on onabotulinumtoxinA or topiramate might improve without them going through a detoxification of the overused medications. As a physician, I would suggest simultaneously decreasing in their acute medications. I think in some cases this approach creates additional improvement and makes the patient feel better. It would be better for their quality of life, as well as for their kidneys and possibly even their brains.

Here are my thoughts on the second question, “Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor), without detoxification?”

If a patient has MOH, can you expect them to improve after being placed on 1 of the 4 monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or its receptor – all of which are either recently approved or currently in development – without suggesting that they decrease their overused acute care medications? Note that erenumab (Aimovig-aaoe) has been approved by the FDA and marketed as of the time of this writing; we expect 2 more products to be approved very soon.

Almost an identical percentage of our audience (38%) said yes. There is evidence in published clinical trials that those patients given these new medications did about as well with or without the presence of MOH, and both groups did better than the placebo patients. Note that most trials prohibited overuse of opiates and butalbital.

I am a firm believer of detoxifying patients from their overused over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications. I believe that opiates and butalbital-containing medications, when overused, are worse for patients than OTCs, NSAIDs, ergot and triptans, but all of these can cause MOH. There are many studies showing that both inpatient and outpatient detoxification alone can really help. However, it is difficult to detoxify patients and some refuse to try this approach.

So, what should we do as physicians? If a patient has MOH, I educate them, try to detoxify them slowly on an outpatient basis, and if I feel it will help, start them on a preventive medication, even before the detoxification begins so they can reach therapeutic levels. In the future, will I use one of the standard preventives, approved or off-label, for migraine prevention (beta blockers, topiramate and other anticonvulsants, antidepressants, angiotensin receptor blockers, onabotulinumtoxinA and others)? It remains to be seen. I am leaning towards the anti CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies and preventive small molecule oral CGRP receptor blockers. While that might be enough to start with, I will continue explaining to my patients why they should actively begin a slow detoxification.

Let us see what some headache specialists said about both questions.

Robert Cowan, MD, FAAN:

There have been studies that show migraine can improve without the discontinuation of medication overuse. But that is not what the question asks. The question as posed is whether MOH can be treated with a preventive medication without detoxification. Since the diagnosis of MOH has, in the past, required the cessation of overuse leading to an improvement in the underlying headache, then technically, the answer would be “no.” But that being said, there is ample evidence that the number of headache days/months and other measures of headache can, in fact, improve with the introduction of a preventive, along with other measures such as lifestyle modification. The other ambiguity in the question has to do with what is meant by “detoxification.” Is this a hospital-based detox, or is a gradual decrease in the offending medicine in combination with the addition of a preventive, still considered “detoxification?” Also, does the response imply a sequential relationship between the detoxification and initiation of the preventive? Without further clarification, this response ratio to the question is very difficult to interpret.

There is animal data that suggests acute migraine medications may promote MOH in susceptible individuals through CGRP-dependent mechanisms and anti-CGRP antibodies may be useful for the MOH (Cephalalgia. 2017;37(6):560-570. doi: 10.1177/0333102416650702). While there are no published CGRP antibody studies that did not exclude MOH patients to my knowledge, an abstract by Silberstein et al at the recent AHS Scientific Meeting reported decreased use of overused medication with fremanazumab (Headache. 2018;58(S2):76-78).

Ira Turner, MD

There is clear data to suggest that it is not necessary to detoxify these patients before starting preventive therapy. This is true for the older and newer medications. In fact, not only do these preventive therapies still work in the presence of medication overuse, but they also help to reduce medication overuse. The one caveat that must be mentioned is that this may not apply to opiate overuse. Opiate over-users were excluded from these studies.

While it is of course our goal to reduce and stop acute medication overuse, it should not be done at the expense of delaying preventive therapy. In fact, it is desirable to do both simultaneously. This applies to oral preventive medications, botulinum toxin and CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

In view of this well-established data, it was quite surprising to me to see the results of the 2 polls cited. It seems as if we still have a lot of educating to do regarding migraine prevention in general and with medication overuse in migraine in particular.

Stewart Tepper, MD

Dr. Tepper did not have time to comment, but suggested we show you an abstract presented at the recent AHS meeting. It shows that erenumab-aaoe helps patients with MOH who have not been detoxified (Headache. 2018;58(S2):160-162).

###

Please write to us at Neurology Reviews Migraine Resource Center ([email protected]) with your opinions.

Alan M. Rapoport, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Migraine Resource Center

Clinical Professor of Neurology

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Los Angeles, California

Neurology Reviews recently shared two poll questions with our Facebook followers about treatment medication overuse headache (MOH). I was very interested to see the results of our poll. While the number of responses was somewhat low, we do get some sense of what respondents are saying. In this commentary, I will first tell you my perspective on the answers and then we will see what some other headache specialists say about the answers to these questions.

Poll Results:

Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?

33 votes

YES, 39%

NO, 61%

Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor) without detoxification?

26 votes

YES, 38%

NO, 62%

My Commentary:

Let me explain in more detail my thoughts on the first question, “Can MOH be treated with preventive medications without detoxification?”

If a patient had the diagnosis of MOH – meaning 15 or more headache days per month for at least 3 months, with use of stronger medications (triptans, ergots, opiates, butalbital-containing medications) for 10 days per month or milder treatment (aspirin, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) for 15 days per month – can they improve by being put on a traditional preventive medication without intentionally reducing their overused acute medications by a detoxification protocol ordered by a doctor or nurse?

Only 39% of our audience said yes. Yet some studies have shown that patients placed on onabotulinumtoxinA or topiramate might improve without them going through a detoxification of the overused medications. As a physician, I would suggest simultaneously decreasing in their acute medications. I think in some cases this approach creates additional improvement and makes the patient feel better. It would be better for their quality of life, as well as for their kidneys and possibly even their brains.

Here are my thoughts on the second question, “Can MOH be treated with the new preventive medications (the monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or receptor), without detoxification?”

If a patient has MOH, can you expect them to improve after being placed on 1 of the 4 monoclonal antibodies to CGRP ligand or its receptor – all of which are either recently approved or currently in development – without suggesting that they decrease their overused acute care medications? Note that erenumab (Aimovig-aaoe) has been approved by the FDA and marketed as of the time of this writing; we expect 2 more products to be approved very soon.

Almost an identical percentage of our audience (38%) said yes. There is evidence in published clinical trials that those patients given these new medications did about as well with or without the presence of MOH, and both groups did better than the placebo patients. Note that most trials prohibited overuse of opiates and butalbital.

I am a firm believer of detoxifying patients from their overused over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications. I believe that opiates and butalbital-containing medications, when overused, are worse for patients than OTCs, NSAIDs, ergot and triptans, but all of these can cause MOH. There are many studies showing that both inpatient and outpatient detoxification alone can really help. However, it is difficult to detoxify patients and some refuse to try this approach.

So, what should we do as physicians? If a patient has MOH, I educate them, try to detoxify them slowly on an outpatient basis, and if I feel it will help, start them on a preventive medication, even before the detoxification begins so they can reach therapeutic levels. In the future, will I use one of the standard preventives, approved or off-label, for migraine prevention (beta blockers, topiramate and other anticonvulsants, antidepressants, angiotensin receptor blockers, onabotulinumtoxinA and others)? It remains to be seen. I am leaning towards the anti CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies and preventive small molecule oral CGRP receptor blockers. While that might be enough to start with, I will continue explaining to my patients why they should actively begin a slow detoxification.

Let us see what some headache specialists said about both questions.

Robert Cowan, MD, FAAN:

There have been studies that show migraine can improve without the discontinuation of medication overuse. But that is not what the question asks. The question as posed is whether MOH can be treated with a preventive medication without detoxification. Since the diagnosis of MOH has, in the past, required the cessation of overuse leading to an improvement in the underlying headache, then technically, the answer would be “no.” But that being said, there is ample evidence that the number of headache days/months and other measures of headache can, in fact, improve with the introduction of a preventive, along with other measures such as lifestyle modification. The other ambiguity in the question has to do with what is meant by “detoxification.” Is this a hospital-based detox, or is a gradual decrease in the offending medicine in combination with the addition of a preventive, still considered “detoxification?” Also, does the response imply a sequential relationship between the detoxification and initiation of the preventive? Without further clarification, this response ratio to the question is very difficult to interpret.

There is animal data that suggests acute migraine medications may promote MOH in susceptible individuals through CGRP-dependent mechanisms and anti-CGRP antibodies may be useful for the MOH (Cephalalgia. 2017;37(6):560-570. doi: 10.1177/0333102416650702). While there are no published CGRP antibody studies that did not exclude MOH patients to my knowledge, an abstract by Silberstein et al at the recent AHS Scientific Meeting reported decreased use of overused medication with fremanazumab (Headache. 2018;58(S2):76-78).

Ira Turner, MD

There is clear data to suggest that it is not necessary to detoxify these patients before starting preventive therapy. This is true for the older and newer medications. In fact, not only do these preventive therapies still work in the presence of medication overuse, but they also help to reduce medication overuse. The one caveat that must be mentioned is that this may not apply to opiate overuse. Opiate over-users were excluded from these studies.