User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

LISTEN NOW: Hospitalist Chris Spoja discusses his decision to pursue a MMM degree

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

Listen to Chris Spoja, MD, a hospitalist with Sound Physicians, explain his decision to pursue a Master’s of Medical Management (MMM) degree.

New Job Isn’t Focus of Everyone Seeking Advanced Management Degrees

Many hospitalists might get an advanced degree in management because they covet a specific job, but that might not be the only reason.

Kevan Pickrel, MD, MHM, a regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians in Southern California, says his decision to get a master’s in healthcare management from the University of Texas at Dallas came down to credibility.

“I got the additional degree for one reason: a seat at the table,” Dr. Pickrel says. “Physicians complain a lot about all the change and the autonomy they have lost but do little about it beyond grumbling at lunch. I believe in hospital medicine as a discipline and believe in the value of the specialty. I wanted to be sure my specialty had a voice, and the only way to set myself apart from ‘just another whining doc’ was to add the letters.”

Making it happen was not a simple task, he says.

“Finding the time wasn’t easy,” he says. “I burned vacation time and leaned on my colleagues a lot. There are any number of physician- or executive-targeted programs offered that make it possible. Possible, but not easy.”

Chris Spoja, DO, a Sound hospitalist in Idaho, says he’d like to prepare himself for a chief medical officer job. He is planning to get his Master of Medical Management (MMM) from the University of Southern California (USC) next year, after he participates in a local leadership program in Idaho, which will allow him to network with people in his area.

“I would like to position myself to at least have that option,” he says, noting that the USC program will allow him to do most of his coursework online, participating in group discussions over Skype or doing work on his own. But he’ll have to visit the campus in Los Angeles for three days once a month.

“It’s not a small commitment,” he says. “But it’s doable.” TH

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Many hospitalists might get an advanced degree in management because they covet a specific job, but that might not be the only reason.

Kevan Pickrel, MD, MHM, a regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians in Southern California, says his decision to get a master’s in healthcare management from the University of Texas at Dallas came down to credibility.

“I got the additional degree for one reason: a seat at the table,” Dr. Pickrel says. “Physicians complain a lot about all the change and the autonomy they have lost but do little about it beyond grumbling at lunch. I believe in hospital medicine as a discipline and believe in the value of the specialty. I wanted to be sure my specialty had a voice, and the only way to set myself apart from ‘just another whining doc’ was to add the letters.”

Making it happen was not a simple task, he says.

“Finding the time wasn’t easy,” he says. “I burned vacation time and leaned on my colleagues a lot. There are any number of physician- or executive-targeted programs offered that make it possible. Possible, but not easy.”

Chris Spoja, DO, a Sound hospitalist in Idaho, says he’d like to prepare himself for a chief medical officer job. He is planning to get his Master of Medical Management (MMM) from the University of Southern California (USC) next year, after he participates in a local leadership program in Idaho, which will allow him to network with people in his area.

“I would like to position myself to at least have that option,” he says, noting that the USC program will allow him to do most of his coursework online, participating in group discussions over Skype or doing work on his own. But he’ll have to visit the campus in Los Angeles for three days once a month.

“It’s not a small commitment,” he says. “But it’s doable.” TH

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Many hospitalists might get an advanced degree in management because they covet a specific job, but that might not be the only reason.

Kevan Pickrel, MD, MHM, a regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians in Southern California, says his decision to get a master’s in healthcare management from the University of Texas at Dallas came down to credibility.

“I got the additional degree for one reason: a seat at the table,” Dr. Pickrel says. “Physicians complain a lot about all the change and the autonomy they have lost but do little about it beyond grumbling at lunch. I believe in hospital medicine as a discipline and believe in the value of the specialty. I wanted to be sure my specialty had a voice, and the only way to set myself apart from ‘just another whining doc’ was to add the letters.”

Making it happen was not a simple task, he says.

“Finding the time wasn’t easy,” he says. “I burned vacation time and leaned on my colleagues a lot. There are any number of physician- or executive-targeted programs offered that make it possible. Possible, but not easy.”

Chris Spoja, DO, a Sound hospitalist in Idaho, says he’d like to prepare himself for a chief medical officer job. He is planning to get his Master of Medical Management (MMM) from the University of Southern California (USC) next year, after he participates in a local leadership program in Idaho, which will allow him to network with people in his area.

“I would like to position myself to at least have that option,” he says, noting that the USC program will allow him to do most of his coursework online, participating in group discussions over Skype or doing work on his own. But he’ll have to visit the campus in Los Angeles for three days once a month.

“It’s not a small commitment,” he says. “But it’s doable.” TH

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Advanced Management Degrees: What Hospitalists Should Consider Before Pursuing One

“That was kind of on-the-job training,” he says. “Just because you’re wearing a higher rank than somebody else doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to be able to effectively motivate them to work within the team and do their job more effectively and help you do your job more effectively.

“That probably was my first time that I was desiring formalized leadership training.”

Dr. Spoja, now 40 and a chief hospitalist in Nampa, Idaho, and regional medical director for Sound Physicians, has made the decision to pursue a Master of Medical Management (MMM) degree—a choice that will mean even crazier hours than he already has now, more hard work, and regular trips from Idaho to Los Angeles. Not exactly a snap to pull off for someone who’s married and has four kids.

But it makes sense for him, because he would like the option of pursuing a chief medical officer position eventually, he says.

“You’re going to get to interact with professors,” he says. “It shows a level of commitment, I think, to leadership.”

A Great Debate

The question of getting an advanced management degree—such as an MMM, a Master of Business Administration (MBA), a Master of Public Health (MPH), or a Master of Hospital Administration (MHA)—poses a great dilemma for many hospitalists.

Job experience and exposure to so many facets of hospital operations make hospitalists good candidates for administrative posts.

But that experience, some hospitalists find, is really only enough to place them into a gray area. Hospitalists’ experience and managerial abilities lay the groundwork for moving up the hospital ladder to the C-suite and might pique their interest in doing so; however, the question remains whether that experience alone is enough. And how to go about deciding whether to get an advanced management degree—and then where and how to pursue it—sets up a complex choice with lots of variables.

Key recommendations from educators, career counselors, and physicians who have gone through the decision process include the following:

- Seek advice from those in the positions you seek;

- Use resources like the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE); and

- Hone your leadership skills through in-house programs before embarking on an expensive and time-consuming formal degree.

Advanced degrees can cost as much as $40,000 per year, just for tuition, and can take a year or two to complete. Options range from an on-campus program to online programs to a combination of the two. The choice of which degree to pursue might be difficult for some, ranging from the traditional MBA to the more quality improvement-focused MMM.

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado-Denver School of Business, says making the choice requires thorough consideration.

“Here’s something that could cost you $75,000, maybe more, depending on what you pick,” says Dr. Guthrie, a frequent speaker on the topic at SHM annual meetings. Plus, “time, energy, distraction, and time away from family. There are significant issues about cost, not just financial. And you have to really have a sense of what’s the return on investment.”

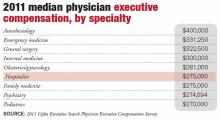

Those with degrees generally do make more money than those without, according to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search and ACPE Physician Executive Compensation Survey. Physician CEOs with an MBA made $24,000 more in 2011 than those without an advanced degree; CMOs with the degree made $44,000 more.

But having a management degree doesn’t automatically translate to more money in every executive position. Physician CEOs with an MMM made $37,000 less than those without a degree; CMOs with an MMM made $51,000 more than those without a degree—a difference based partially on the reality that an MMM often is a degree pursued by aspiring CMOs.

—Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support, career counselor, American College of Physician Executives

Mission C

One of the most fundamental questions facing hospitalists with advancement aspirations is “Can I get to the C-suite without that extra degree?”

In some cases, the answer is “no.”

At Banner Health, a system with facilities throughout the western U.S., all C-suite executives have to have an advanced degree of some kind, generally an MBA or MHA, says Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region at Banner. She recently hired former hospitalist Steve Narang, MD, MHCM, FAAP, MBA, as CEO of Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

It wasn’t merely Dr. Narang’s MBA that earned him the position. Bollinger says his knowledge, experience, and her own confidence in him during a transitional period in the U.S. healthcare landscape played key roles in the decision.

But the degree rule is in place, she notes, because at Banner, the degree is seen as so crucial to cultivating the kind of knowledge and person capable of being a good hospital administrator.

“His business degree is clearly part of him and part of his effectiveness,” Bollinger says. “So I’m not sure that I could have observed in Steve the things that I observed in Steve had not he not been more globally trained, if you will.”

Doctors and administrators, she says, tend not to think alike.

“I would say physicians, medical staff members of a hospital, and administrators of a hospital historically, in a stereotyped way, have been predisposed to be at odds with one another,” she says. The formal education is a way to expand a physician’s way of thinking, she adds.

“The business thinking and financial aptitude that is required at our big hospitals is such that it would be a stretch for somebody who didn’t either have a degree or was deep into it from an experience standpoint,” she says. “For me, that was very significant.”

When the Cleveland Clinic was looking for a new CEO at South Pointe Hospital in 2012, they tapped a doctor without a management degree—Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist who had been chief operating officer at another hospital within the system. At the time of Dr. Harte’s promotion, Cleveland Clinic Regional Hospitals President David Bronson, MD, who also does not have an advanced management degree, praised Dr. Harte’s experience.

“His expertise in quality will help South Pointe Hospital continue to provide the best experience for patients,” Dr. Bronson said in a news release at the time.

What can’t be denied, however, is that many physicians in executive roles do, in fact, have post-graduate degrees. According to the ACPE’s survey, 40% of the doctors surveyed had an MBA, an MMM, an MPH, or an MHA. Of those, 52% had an MBA. The survey includes everyone from CEOs to associate professors.

Even so, an advanced degree is not a magic wand.

“The MBA doesn’t get you a job,” Dr. Guthrie says. “People are looking at what you can do and what you’ve done and not at how smart and schooled you are. It’s helpful. It’s useful. I believe that the current terminology is ‘preferred ‘ or ‘encouraged,’ but it isn’t essential.”

Due Diligence

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ West Region and chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, earned his business degree at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh. He says it’s important that hospitalists have experience before pursuing the degree. This will help them “see the business side through a clinician’s eyes first.”

“There were some people in my cohort at Carnegie Mellon who didn’t have enough experience to make the programmatic elements all that relevant to their practice, to their world,” he says. “You want to be able to reflect on the mistakes that you’ve made and the things that you’ve done really well and have a deeper understanding of what worked and what didn’t if you want to get the most out of it.”

That said, he acknowledges that those circumstances apparently aren’t a requirement for success—one of his Carnegie Mellon classmates is a CEO.

Which kind of degree to pursue is a whole other question. Experts say that while getting the degree will give you a leg up to some extent, certain degrees will be preferable over others depending on what you want to do. For someone who wants to run a start-up medical company, an MBA might be best. For someone who wants to work in quality improvement, the MMM might be best.

An online degree—or at least one that’s completed partially online—might be more practical for a doctor who wants to continue with practice. Some programs require students to be on campus for every class, and some require occasional on-campus work, while others never require a doctor to set foot on a campus.

“The issue becomes, what are the individual’s degrees of freedom?” Dr. Guthrie says. “Individuals’ personal circumstances really drive which kind of program they look at. And then where they’re located may have a lot to do with what they choose.”

Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support at the ACPE and the primary career counselor there, says that when doctors ask her about getting an advanced management degree, she starts by asking them what they want to be doing in three to five years. If the answer is not realistic, she helps them revise those goals. Once that’s settled, she helps them figure out whether the degree makes sense.

From that point, she says, there is no hard-and-fast rule.

“It’s very driven by the individual,” she says.

Plunging into management training probably isn’t best suited for those fresh out of residency with little leadership exposure at their institution or for those only a few years from retirement.

She tries to open physicians’ eyes to the wide range of C-suite positions available, including some they might not have heard of. Chief medical officer is traditionally what doctors think of when they consider executive positions, but other positions, such as chief information technology officer or chief patient experience officer, should be considered.

“The conversations are changing very much,” Apple says. “There are a lot of other emerging roles. I think sometimes that the varied opportunities that exist, whether or not people know about them at the beginning of our conversation, can really color the decisions that people make later.”

A love of learning should be a main motivator. Dr. Guthrie emphasizes the importance of pursuing a degree that you’re interested in. Without that interest, he says, a hospitalist might want to reconsider.

“It goes by very quickly—it’s also fun,” he says. “Physicians are great students usually, and by the time they get into it, [they] realize, ‘You know, this is really kind of a hoot.’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

“That was kind of on-the-job training,” he says. “Just because you’re wearing a higher rank than somebody else doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to be able to effectively motivate them to work within the team and do their job more effectively and help you do your job more effectively.

“That probably was my first time that I was desiring formalized leadership training.”

Dr. Spoja, now 40 and a chief hospitalist in Nampa, Idaho, and regional medical director for Sound Physicians, has made the decision to pursue a Master of Medical Management (MMM) degree—a choice that will mean even crazier hours than he already has now, more hard work, and regular trips from Idaho to Los Angeles. Not exactly a snap to pull off for someone who’s married and has four kids.

But it makes sense for him, because he would like the option of pursuing a chief medical officer position eventually, he says.

“You’re going to get to interact with professors,” he says. “It shows a level of commitment, I think, to leadership.”

A Great Debate

The question of getting an advanced management degree—such as an MMM, a Master of Business Administration (MBA), a Master of Public Health (MPH), or a Master of Hospital Administration (MHA)—poses a great dilemma for many hospitalists.

Job experience and exposure to so many facets of hospital operations make hospitalists good candidates for administrative posts.

But that experience, some hospitalists find, is really only enough to place them into a gray area. Hospitalists’ experience and managerial abilities lay the groundwork for moving up the hospital ladder to the C-suite and might pique their interest in doing so; however, the question remains whether that experience alone is enough. And how to go about deciding whether to get an advanced management degree—and then where and how to pursue it—sets up a complex choice with lots of variables.

Key recommendations from educators, career counselors, and physicians who have gone through the decision process include the following:

- Seek advice from those in the positions you seek;

- Use resources like the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE); and

- Hone your leadership skills through in-house programs before embarking on an expensive and time-consuming formal degree.

Advanced degrees can cost as much as $40,000 per year, just for tuition, and can take a year or two to complete. Options range from an on-campus program to online programs to a combination of the two. The choice of which degree to pursue might be difficult for some, ranging from the traditional MBA to the more quality improvement-focused MMM.

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado-Denver School of Business, says making the choice requires thorough consideration.

“Here’s something that could cost you $75,000, maybe more, depending on what you pick,” says Dr. Guthrie, a frequent speaker on the topic at SHM annual meetings. Plus, “time, energy, distraction, and time away from family. There are significant issues about cost, not just financial. And you have to really have a sense of what’s the return on investment.”

Those with degrees generally do make more money than those without, according to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search and ACPE Physician Executive Compensation Survey. Physician CEOs with an MBA made $24,000 more in 2011 than those without an advanced degree; CMOs with the degree made $44,000 more.

But having a management degree doesn’t automatically translate to more money in every executive position. Physician CEOs with an MMM made $37,000 less than those without a degree; CMOs with an MMM made $51,000 more than those without a degree—a difference based partially on the reality that an MMM often is a degree pursued by aspiring CMOs.

—Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support, career counselor, American College of Physician Executives

Mission C

One of the most fundamental questions facing hospitalists with advancement aspirations is “Can I get to the C-suite without that extra degree?”

In some cases, the answer is “no.”

At Banner Health, a system with facilities throughout the western U.S., all C-suite executives have to have an advanced degree of some kind, generally an MBA or MHA, says Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region at Banner. She recently hired former hospitalist Steve Narang, MD, MHCM, FAAP, MBA, as CEO of Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

It wasn’t merely Dr. Narang’s MBA that earned him the position. Bollinger says his knowledge, experience, and her own confidence in him during a transitional period in the U.S. healthcare landscape played key roles in the decision.

But the degree rule is in place, she notes, because at Banner, the degree is seen as so crucial to cultivating the kind of knowledge and person capable of being a good hospital administrator.

“His business degree is clearly part of him and part of his effectiveness,” Bollinger says. “So I’m not sure that I could have observed in Steve the things that I observed in Steve had not he not been more globally trained, if you will.”

Doctors and administrators, she says, tend not to think alike.

“I would say physicians, medical staff members of a hospital, and administrators of a hospital historically, in a stereotyped way, have been predisposed to be at odds with one another,” she says. The formal education is a way to expand a physician’s way of thinking, she adds.

“The business thinking and financial aptitude that is required at our big hospitals is such that it would be a stretch for somebody who didn’t either have a degree or was deep into it from an experience standpoint,” she says. “For me, that was very significant.”

When the Cleveland Clinic was looking for a new CEO at South Pointe Hospital in 2012, they tapped a doctor without a management degree—Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist who had been chief operating officer at another hospital within the system. At the time of Dr. Harte’s promotion, Cleveland Clinic Regional Hospitals President David Bronson, MD, who also does not have an advanced management degree, praised Dr. Harte’s experience.

“His expertise in quality will help South Pointe Hospital continue to provide the best experience for patients,” Dr. Bronson said in a news release at the time.

What can’t be denied, however, is that many physicians in executive roles do, in fact, have post-graduate degrees. According to the ACPE’s survey, 40% of the doctors surveyed had an MBA, an MMM, an MPH, or an MHA. Of those, 52% had an MBA. The survey includes everyone from CEOs to associate professors.

Even so, an advanced degree is not a magic wand.

“The MBA doesn’t get you a job,” Dr. Guthrie says. “People are looking at what you can do and what you’ve done and not at how smart and schooled you are. It’s helpful. It’s useful. I believe that the current terminology is ‘preferred ‘ or ‘encouraged,’ but it isn’t essential.”

Due Diligence

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ West Region and chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, earned his business degree at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh. He says it’s important that hospitalists have experience before pursuing the degree. This will help them “see the business side through a clinician’s eyes first.”

“There were some people in my cohort at Carnegie Mellon who didn’t have enough experience to make the programmatic elements all that relevant to their practice, to their world,” he says. “You want to be able to reflect on the mistakes that you’ve made and the things that you’ve done really well and have a deeper understanding of what worked and what didn’t if you want to get the most out of it.”

That said, he acknowledges that those circumstances apparently aren’t a requirement for success—one of his Carnegie Mellon classmates is a CEO.

Which kind of degree to pursue is a whole other question. Experts say that while getting the degree will give you a leg up to some extent, certain degrees will be preferable over others depending on what you want to do. For someone who wants to run a start-up medical company, an MBA might be best. For someone who wants to work in quality improvement, the MMM might be best.

An online degree—or at least one that’s completed partially online—might be more practical for a doctor who wants to continue with practice. Some programs require students to be on campus for every class, and some require occasional on-campus work, while others never require a doctor to set foot on a campus.

“The issue becomes, what are the individual’s degrees of freedom?” Dr. Guthrie says. “Individuals’ personal circumstances really drive which kind of program they look at. And then where they’re located may have a lot to do with what they choose.”

Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support at the ACPE and the primary career counselor there, says that when doctors ask her about getting an advanced management degree, she starts by asking them what they want to be doing in three to five years. If the answer is not realistic, she helps them revise those goals. Once that’s settled, she helps them figure out whether the degree makes sense.

From that point, she says, there is no hard-and-fast rule.

“It’s very driven by the individual,” she says.

Plunging into management training probably isn’t best suited for those fresh out of residency with little leadership exposure at their institution or for those only a few years from retirement.

She tries to open physicians’ eyes to the wide range of C-suite positions available, including some they might not have heard of. Chief medical officer is traditionally what doctors think of when they consider executive positions, but other positions, such as chief information technology officer or chief patient experience officer, should be considered.

“The conversations are changing very much,” Apple says. “There are a lot of other emerging roles. I think sometimes that the varied opportunities that exist, whether or not people know about them at the beginning of our conversation, can really color the decisions that people make later.”

A love of learning should be a main motivator. Dr. Guthrie emphasizes the importance of pursuing a degree that you’re interested in. Without that interest, he says, a hospitalist might want to reconsider.

“It goes by very quickly—it’s also fun,” he says. “Physicians are great students usually, and by the time they get into it, [they] realize, ‘You know, this is really kind of a hoot.’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

“That was kind of on-the-job training,” he says. “Just because you’re wearing a higher rank than somebody else doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to be able to effectively motivate them to work within the team and do their job more effectively and help you do your job more effectively.

“That probably was my first time that I was desiring formalized leadership training.”

Dr. Spoja, now 40 and a chief hospitalist in Nampa, Idaho, and regional medical director for Sound Physicians, has made the decision to pursue a Master of Medical Management (MMM) degree—a choice that will mean even crazier hours than he already has now, more hard work, and regular trips from Idaho to Los Angeles. Not exactly a snap to pull off for someone who’s married and has four kids.

But it makes sense for him, because he would like the option of pursuing a chief medical officer position eventually, he says.

“You’re going to get to interact with professors,” he says. “It shows a level of commitment, I think, to leadership.”

A Great Debate

The question of getting an advanced management degree—such as an MMM, a Master of Business Administration (MBA), a Master of Public Health (MPH), or a Master of Hospital Administration (MHA)—poses a great dilemma for many hospitalists.

Job experience and exposure to so many facets of hospital operations make hospitalists good candidates for administrative posts.

But that experience, some hospitalists find, is really only enough to place them into a gray area. Hospitalists’ experience and managerial abilities lay the groundwork for moving up the hospital ladder to the C-suite and might pique their interest in doing so; however, the question remains whether that experience alone is enough. And how to go about deciding whether to get an advanced management degree—and then where and how to pursue it—sets up a complex choice with lots of variables.

Key recommendations from educators, career counselors, and physicians who have gone through the decision process include the following:

- Seek advice from those in the positions you seek;

- Use resources like the American College of Physician Executives (ACPE); and

- Hone your leadership skills through in-house programs before embarking on an expensive and time-consuming formal degree.

Advanced degrees can cost as much as $40,000 per year, just for tuition, and can take a year or two to complete. Options range from an on-campus program to online programs to a combination of the two. The choice of which degree to pursue might be difficult for some, ranging from the traditional MBA to the more quality improvement-focused MMM.

Michael Guthrie, MD, MBA, executive-in-residence at the University of Colorado-Denver School of Business, says making the choice requires thorough consideration.

“Here’s something that could cost you $75,000, maybe more, depending on what you pick,” says Dr. Guthrie, a frequent speaker on the topic at SHM annual meetings. Plus, “time, energy, distraction, and time away from family. There are significant issues about cost, not just financial. And you have to really have a sense of what’s the return on investment.”

Those with degrees generally do make more money than those without, according to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search and ACPE Physician Executive Compensation Survey. Physician CEOs with an MBA made $24,000 more in 2011 than those without an advanced degree; CMOs with the degree made $44,000 more.

But having a management degree doesn’t automatically translate to more money in every executive position. Physician CEOs with an MMM made $37,000 less than those without a degree; CMOs with an MMM made $51,000 more than those without a degree—a difference based partially on the reality that an MMM often is a degree pursued by aspiring CMOs.

—Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support, career counselor, American College of Physician Executives

Mission C

One of the most fundamental questions facing hospitalists with advancement aspirations is “Can I get to the C-suite without that extra degree?”

In some cases, the answer is “no.”

At Banner Health, a system with facilities throughout the western U.S., all C-suite executives have to have an advanced degree of some kind, generally an MBA or MHA, says Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region at Banner. She recently hired former hospitalist Steve Narang, MD, MHCM, FAAP, MBA, as CEO of Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

It wasn’t merely Dr. Narang’s MBA that earned him the position. Bollinger says his knowledge, experience, and her own confidence in him during a transitional period in the U.S. healthcare landscape played key roles in the decision.

But the degree rule is in place, she notes, because at Banner, the degree is seen as so crucial to cultivating the kind of knowledge and person capable of being a good hospital administrator.

“His business degree is clearly part of him and part of his effectiveness,” Bollinger says. “So I’m not sure that I could have observed in Steve the things that I observed in Steve had not he not been more globally trained, if you will.”

Doctors and administrators, she says, tend not to think alike.

“I would say physicians, medical staff members of a hospital, and administrators of a hospital historically, in a stereotyped way, have been predisposed to be at odds with one another,” she says. The formal education is a way to expand a physician’s way of thinking, she adds.

“The business thinking and financial aptitude that is required at our big hospitals is such that it would be a stretch for somebody who didn’t either have a degree or was deep into it from an experience standpoint,” she says. “For me, that was very significant.”

When the Cleveland Clinic was looking for a new CEO at South Pointe Hospital in 2012, they tapped a doctor without a management degree—Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist who had been chief operating officer at another hospital within the system. At the time of Dr. Harte’s promotion, Cleveland Clinic Regional Hospitals President David Bronson, MD, who also does not have an advanced management degree, praised Dr. Harte’s experience.

“His expertise in quality will help South Pointe Hospital continue to provide the best experience for patients,” Dr. Bronson said in a news release at the time.

What can’t be denied, however, is that many physicians in executive roles do, in fact, have post-graduate degrees. According to the ACPE’s survey, 40% of the doctors surveyed had an MBA, an MMM, an MPH, or an MHA. Of those, 52% had an MBA. The survey includes everyone from CEOs to associate professors.

Even so, an advanced degree is not a magic wand.

“The MBA doesn’t get you a job,” Dr. Guthrie says. “People are looking at what you can do and what you’ve done and not at how smart and schooled you are. It’s helpful. It’s useful. I believe that the current terminology is ‘preferred ‘ or ‘encouraged,’ but it isn’t essential.”

Due Diligence

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chief medical officer of Sound Physicians’ West Region and chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, earned his business degree at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh. He says it’s important that hospitalists have experience before pursuing the degree. This will help them “see the business side through a clinician’s eyes first.”

“There were some people in my cohort at Carnegie Mellon who didn’t have enough experience to make the programmatic elements all that relevant to their practice, to their world,” he says. “You want to be able to reflect on the mistakes that you’ve made and the things that you’ve done really well and have a deeper understanding of what worked and what didn’t if you want to get the most out of it.”

That said, he acknowledges that those circumstances apparently aren’t a requirement for success—one of his Carnegie Mellon classmates is a CEO.

Which kind of degree to pursue is a whole other question. Experts say that while getting the degree will give you a leg up to some extent, certain degrees will be preferable over others depending on what you want to do. For someone who wants to run a start-up medical company, an MBA might be best. For someone who wants to work in quality improvement, the MMM might be best.

An online degree—or at least one that’s completed partially online—might be more practical for a doctor who wants to continue with practice. Some programs require students to be on campus for every class, and some require occasional on-campus work, while others never require a doctor to set foot on a campus.

“The issue becomes, what are the individual’s degrees of freedom?” Dr. Guthrie says. “Individuals’ personal circumstances really drive which kind of program they look at. And then where they’re located may have a lot to do with what they choose.”

Rebekah Apple, MA, senior manager of physician services and support at the ACPE and the primary career counselor there, says that when doctors ask her about getting an advanced management degree, she starts by asking them what they want to be doing in three to five years. If the answer is not realistic, she helps them revise those goals. Once that’s settled, she helps them figure out whether the degree makes sense.

From that point, she says, there is no hard-and-fast rule.

“It’s very driven by the individual,” she says.

Plunging into management training probably isn’t best suited for those fresh out of residency with little leadership exposure at their institution or for those only a few years from retirement.

She tries to open physicians’ eyes to the wide range of C-suite positions available, including some they might not have heard of. Chief medical officer is traditionally what doctors think of when they consider executive positions, but other positions, such as chief information technology officer or chief patient experience officer, should be considered.

“The conversations are changing very much,” Apple says. “There are a lot of other emerging roles. I think sometimes that the varied opportunities that exist, whether or not people know about them at the beginning of our conversation, can really color the decisions that people make later.”

A love of learning should be a main motivator. Dr. Guthrie emphasizes the importance of pursuing a degree that you’re interested in. Without that interest, he says, a hospitalist might want to reconsider.

“It goes by very quickly—it’s also fun,” he says. “Physicians are great students usually, and by the time they get into it, [they] realize, ‘You know, this is really kind of a hoot.’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer living in South Florida.

LISTEN NOW: M.D. Anderson hospitalists discuss caring for cancer patients

Josiah Halm, MD, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, discuss the breadth of care provided to cancer patients, a risk assessment being developed there on readmission risk, and factors in care that go beyond the medical.

Josiah Halm, MD, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, discuss the breadth of care provided to cancer patients, a risk assessment being developed there on readmission risk, and factors in care that go beyond the medical.

Josiah Halm, MD, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, discuss the breadth of care provided to cancer patients, a risk assessment being developed there on readmission risk, and factors in care that go beyond the medical.

10 Things Oncologists Think Hospitalists Need to Know

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Things you need to know

An occasional series providing specialty-specific advice for hospitalists from experts in the field.

COMING UP: 10 Things Endocrinologists Want HM to Know Archived: @the-hospitalist.org

- 10 Things Infectious Disease

- 12 Things Cardiology

- 12 Things Nephrology

- 12 Things Billing & Coding

Cancer patients can be some of the most complicated and high-stakes patients who come into a hospitalist’s care.

The issues faced by such patients are three-pronged: Besides the effects of the cancer itself, these often elderly patients also grapple with the side effects of treatment and other medical issues.

The Hospitalist sought tips for caring for hospitalized cancer patients from a half-dozen experts in hematology and oncology. Here are the 10 most common pieces of advice they had for hospitalists caring for cancer patients.

1 Know the History

This includes the subtleties of the patient history, which can be quite involved, says Fadlo R. Khuri, MD, FACP, deputy director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and chair of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“Part of that history may be obtained from the patient and the patient’s family, but if the treatment has been evolving over time, you need to get in touch with the treating physician or at least have access to the records of the patient’s treatment,” he says. “The arsenal of drugs that we use against cancer has expanded dramatically and in different directions. Now we have tremendous technological innovations with very focused radiation or very refined surgery, and not just novel chemotherapy but also targeted therapies that can target a specific Achilles heel of cancer.”

Basically, it is important for hospitalists to know exactly “what you are dealing with.”

“That’s a lot of information that the hospitalist needs to know. Whom do I contact? Whom do I need to access, not just on the web, but in person, to understand what this patient is going through?” he adds.

With many patients, time is of the essence. This is part of the reason why it’s so important to get a complete history and full picture of a patient’s treatment right away, Dr. Khuri says.

“The patient with cancer often presents in worse shape than patients with other diseases,” he says. “Therefore, with patients with cancer or patients with other really life-threatening illness, you generally have less time to figure out what is going on.”

2 Communication Is Paramount

“The reason that communication is important is to convey the right message to the patient,” says Suresh Ramalingam, MD, professor and director of medical oncology and the lung cancer program at the Emory School of Medicine. “An oncologist who’s been following a patient for a year and a half…I would think has some insight that he or she can provide the hospitalist to manage the acute illness that the patient is admitted with.

“The other thing is many times a patient comes in the hospital and the first question they have is, ‘Does this mean my cancer is getting worse? What is the next option for me? And am I going to die right away?’ And they’re going to ask this question of whomever they see first. Having the oncologist’s thoughts on the patient’s overall status of cancer is important to address such issues.”

Dr. Ramalingam says that a situation that used to occur, but is now less frequent, is frantic calls from a patient in a hospital bed saying, “The hospitalist just walked in, and he said I’m going to die in three weeks. You never told me about that.”

When that happens, “we have to go back and talk to the patient and reassure the patient that that’s not the case,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

3 Treating Cancer Is More Than Treating Cancer

At the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where a pilot hospitalist program that began six years ago has grown into a permanent part of the center, treatment comes from all angles, not just medical, says Josiah Halm, MD, MS, FACP, FHM, CMQ, and Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, assistant professors of general internal medicine at the center.

“I think the biggest thing is to understand that a cancer patient is very complex and there’s much more than the physical component,” says Dr. Gadiraju, one of nine hospitalists at MD Anderson. “There’s an emotional component. There’s a mental component. There’s the family that’s involved.

“One of the biggest things that we do is not just support the patient physically and medically but also emotionally and mentally. And we provide very good family support working as part of an interdisciplinary team.”

4 Know the Baseline

Dr. Khuri says hospitalists should start by seeking answers to some simple questions.

“What kind of situation were they in when they began to deteriorate? Was this patient walking, talking, healthy, eating, working? And is this an acute deterioration, or is this a gradual deterioration?” he says.

The hospitalist caring for a patient with an acute decline might play a major role in the outcome.

“Some of these acute, precipitating events may be treatable, and the hospitalist may be—forgive my language—Johnny-on-the-spot—and may be able to make a major difference in turning that patient around,” he says.

5 Fight for DVT prophylaxis

When patients should be given prophylaxis for DVT, do not be deterred from doing so by the treating oncologist, says Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and interim chief of the division of hospital medicine and patient safety officer for the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. For patients undergoing chemotherapy, oncologists might be concerned about the potential for bleeding events, but it’s important to “get with the guidelines,” Dr. Manjarrez says.

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with,” he says. “Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.

“Sometimes, hematologists or oncologists might actually cancel your order.”

6 ‘More Is Better’ for Genome Analysis

With a fine-needle biopsy, there might not be enough specimen left for molecular analysis, Dr. Ramalingam explains.

“The purpose of the biopsy is no longer just diagnostic; it has significant therapeutic implications. Therefore, getting as much tissue [as possible] during that initial diagnostic biopsy is very helpful, because we conduct detailed molecular studies on these specimens,” he says. “If you don’t get enough specimen in the first biopsy, but you just have enough to make a diagnosis of the type of cancer, then you have to resort to a second biopsy. So, more is better when it comes to tissue.”

7 Consider Pediatric Test Tubes for Pancytopenic Patients

Using smaller test tubes will lower the potential for anemia caused by frequent blood draws, Dr. Manjarrez says. Recent evidence suggests that hospital-acquired anemia prolongs hospital costs, length of stay, and mortality risk—all directly proportional to the level of anemia.1

“We’re causing [patients] to be more anemic with blood draws,” he says. “When you have cancer patients who get chemotherapy, their bone marrow is wiped out by the chemotherapy. So what happens is that you end up in the cycle where you have to keep transfusing these patients. The more blood draws that you get from them, the more we’re exacerbating it.”

8 Respect Your Turf, Their Turf

Dr. Manjarrez says the best way to ensure the hem-onc specialists respect the hospitalist’s turf, and vice versa, is to discuss the treatment parameters ahead of time.

“Try and negotiate comanagement deals with your hematologist-oncologist colleagues before you enter into comanagement relationships with them,” he says.

One particularly sticky situation is when a patient is admitted with the expectation that the hospitalist will be caring for acute issues like infection or cancer-related pain, but then the hospitalization is extended because the oncologist wants to start chemotherapy.

“That can be a problem,” he says. “Agree with your hematology-oncology colleagues what you’re going to do in advance, as much as you can.”

“Oftentimes, hospitalists can be undermined by the oncologists that they’re managing their patients with. Make sure that you stick to your guns and make sure that you’re strong about giving DVT prophylaxis to these patients, unless they truly meet exclusion criteria for that prophylaxis.”

—Efrén Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine, interim chief, division of hospital medicine, patient safety officer, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

9 Be Cautious in Using Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (GCSF)

The medication is used to stimulate the body to produce more white blood cells, which sometimes is needed after chemotherapy. They are good for certain situations but should be handled with care, says Lowell Schnipper, MD, clinical director of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cancer Center in Boston.

“Because it’s unnecessary and very expensive,” says Dr. Schnipper, who is chair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Value of Care Task Force. “If this is a chemotherapy regimen that has a risk of fever and neutropenia in the context of the chemotherapy, [and] the odds of having that complication are 20% percent or higher with a chemotherapy regimen, we suggest using GCSF.”

If not, then GCSF should be avoided, he says.

Such decisions likely will fall to the treating oncologist, but Dr. Schnipper says it is a topic with which hospitalists should be familiar.

10 Rethink Imaging

“If you get a PET scan in the hospital and a patient is admitted for a different diagnosis, there’s a good likelihood that it’s not going to be reimbursed,” Dr. Ramalingam says.

Plus, he says, a scan done in the hospital could cloud the radiographic findings used to make decisions.

“For instance, for someone with pneumonia, the infiltrate might be difficult to differentiate from cancer,” he says.

Tom Collins is a freelance author in South Florida and longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

Palliative Care Patient Transitions Challenging For Hospitalists, Oncologists

When should treating a cancer patient become more about controlling symptoms and making the patient comfortable than about trying to slow the cancer itself?

Hospitalists, who often care for patients in the worst stages of health, regularly make important observations that result in a patient transitioning to hospice care. When such a case is suspected, careful discussions with the treating oncologist, the patient, and the patient’s family should be held.

Determining how and when to have those discussions can be tricky, experts say.

“You have to understand the family dynamic before anything else,” Dr. Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, says. “You have to understand the patient, how mentally and emotionally ready they are to have that conversation. And how ready [the family] is to have that conversation.”

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea. When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”—Dr. Halm

One treatment course to question, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Choosing Wisely list, is the use of cancer treatments at the end of life. The society recommends that patients with advanced, solid tumors be shifted to palliative care when previous treatments haven’t worked and no additional, evidence-based treatments are available; when patients can’t care for themselves and spend most of their time in a chair or a bed; and when they aren’t eligible for a clinical trial.

Dr. Lowell Schnipper, MD, who led the group that created the list, says this guidance can be helpful to hospitalists. He says hospitalists should be aware of the patient’s “trajectory” and should only call in consultants when “something clearly suggests that this situation is reversible.”

Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, MD says conferring with the oncologist before talking to a patient about hospice care is crucial, because new treatments are available that can bring about remarkable turnarounds, even in patients in dire condition.

“For certain subsets of patients with cancer, there are specific, molecularly targeted therapies that produce so-called ‘Lazarus responses,’ he explains. “They are bed-bound, totally crippled one day, and a few days after you give them the drug, they’re like a new person walking into your clinic.”

Dr. Josiah Halm, MD, says that, working at a comprehensive cancer center like M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, he sometimes sees patients who won’t accept the initial determination that aggressive treatment is not a good option when they have poor performance status. They sometimes still demand “small chemo,” or “a little chemo,” from their oncologist.

“Sometimes these patients would have gone elsewhere. They’ve been told, ‘Look, what you need is hospice; there’s nothing else we can do.’ And they’ll come here,” he says. “Either we’re telling them the same thing and that’s when they accept it or [they are] still demanding treatment. Sometimes they may be eligible for cancer treatment after being reviewed by our oncologists.

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea,” he adds. “When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”

Dr. Halm sometimes asks patients what he can do to make them feel better “today,” with emphasis on the moment. In this way, he gets patients to focus on one main symptom that is causing them the most discomfort.

When patients don’t want to accept palliative-only care, Dr. Gadiraju says, it’s helpful to get them to realize they are still getting treatment, even if the nature of the treatment is different.

“We don’t want the patient to ever feel like we’re giving up on them,” he says.

When should treating a cancer patient become more about controlling symptoms and making the patient comfortable than about trying to slow the cancer itself?

Hospitalists, who often care for patients in the worst stages of health, regularly make important observations that result in a patient transitioning to hospice care. When such a case is suspected, careful discussions with the treating oncologist, the patient, and the patient’s family should be held.

Determining how and when to have those discussions can be tricky, experts say.

“You have to understand the family dynamic before anything else,” Dr. Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, says. “You have to understand the patient, how mentally and emotionally ready they are to have that conversation. And how ready [the family] is to have that conversation.”

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea. When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”—Dr. Halm

One treatment course to question, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Choosing Wisely list, is the use of cancer treatments at the end of life. The society recommends that patients with advanced, solid tumors be shifted to palliative care when previous treatments haven’t worked and no additional, evidence-based treatments are available; when patients can’t care for themselves and spend most of their time in a chair or a bed; and when they aren’t eligible for a clinical trial.

Dr. Lowell Schnipper, MD, who led the group that created the list, says this guidance can be helpful to hospitalists. He says hospitalists should be aware of the patient’s “trajectory” and should only call in consultants when “something clearly suggests that this situation is reversible.”

Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, MD says conferring with the oncologist before talking to a patient about hospice care is crucial, because new treatments are available that can bring about remarkable turnarounds, even in patients in dire condition.

“For certain subsets of patients with cancer, there are specific, molecularly targeted therapies that produce so-called ‘Lazarus responses,’ he explains. “They are bed-bound, totally crippled one day, and a few days after you give them the drug, they’re like a new person walking into your clinic.”

Dr. Josiah Halm, MD, says that, working at a comprehensive cancer center like M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, he sometimes sees patients who won’t accept the initial determination that aggressive treatment is not a good option when they have poor performance status. They sometimes still demand “small chemo,” or “a little chemo,” from their oncologist.

“Sometimes these patients would have gone elsewhere. They’ve been told, ‘Look, what you need is hospice; there’s nothing else we can do.’ And they’ll come here,” he says. “Either we’re telling them the same thing and that’s when they accept it or [they are] still demanding treatment. Sometimes they may be eligible for cancer treatment after being reviewed by our oncologists.

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea,” he adds. “When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”

Dr. Halm sometimes asks patients what he can do to make them feel better “today,” with emphasis on the moment. In this way, he gets patients to focus on one main symptom that is causing them the most discomfort.