User login

More proof that fruit, vegetables, whole grains may stop diabetes

In a pooled analysis of three large prospective American cohorts, people with the highest versus lowest total consumption of whole grain foods had a significantly lower risk of type 2 diabetes.

“These findings provide further support for the current recommendations of increasing whole grain consumption as part of a healthy diet for the prevention of type 2 diabetes,” wrote the authors led by Yang Hu, a doctoral student at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

Similarly, in a large European case-cohort study, people with higher values for plasma vitamin C and carotenoids (fruit and vegetable intake) had a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes.

“This study suggests that even a modest increase in fruit and vegetable intake could help to prevent type 2 diabetes ... regardless of whether the increase is among people with initially low or high intake,” wrote Ju-Sheng Zheng, PhD, University of Cambridge (England), and colleagues.

Individual whole grain foods

Previous studies have shown that high consumption of whole grains is associated with a lower risk of developing chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and some types of cancer, Mr. Hu and colleagues wrote.

Although research has shown that whole grain breakfast cereal and brown rice are linked with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, the effect of other commonly consumed whole grain foods – which contain different amounts of dietary fiber, antioxidants, magnesium, and phytochemicals – has not been established.

Mr. Hu and colleagues analyzed pooled data from 158,259 U.S. women who participated in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017) and 36,525 U.S. men who took part in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986-2016), who were free of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Participants’ baseline consumption of seven types of whole grain foods – whole grain breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, added bran, wheat germ, and popcorn – was based on self-replies to food frequency questionnaires.

During an average 24-year follow-up, 18,629 participants developed type 2 diabetes.

After adjusting for body mass index, lifestyle, and dietary risk factors, participants in the highest quintile of total whole grain consumption had a 29% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes than those in the lowest quintile.

The most commonly consumed whole grain foods were whole grain cold breakfast cereal, dark bread, and popcorn.

Compared with eating less than one serving a month of whole grain cold breakfast cereal or dark bread, eating one or more servings a day was associated with a 19% and 21% lower risk of developing diabetes, respectively.

For popcorn, a J-shaped association was found for intake, where the risk of type 2 diabetes was not significantly raised until consumption exceeded about one serving a day, which led to about an 8% increased risk of developing diabetes – likely related to fat and sugar added to the popcorn, the researchers wrote.

For the less frequently consumed whole grain foods, compared with eating less than one serving a month of oatmeal, brown rice, added bran, or wheat germ, participants who ate two or more servings a week had a 21%, 12%, 15%, and 12% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, respectively.

Lean or overweight individuals had a greater decreased risk of diabetes with increased consumption of whole grain foods; however, because individuals with obesity have a higher risk of diabetes, even a small decrease in risk is still meaningful.

Limitations include the study was observational and may have had unknown confounders, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations, the authors note.

‘Five a day’ fruits and vegetables

Only one previous small published study from the United Kingdom has examined how blood levels of vitamin C and carotenoids are associated with incident type 2 diabetes, Dr. Zheng and colleagues wrote.

They investigated the relationship in 9,754 adults who developed new-onset type 2 diabetes and a comparison group of 13,662 adults who remained diabetes free during an average 9.7-year follow-up, from 340,234 participants in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition–InterAct study.

Participants were from Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, and incident type 2 diabetes occurred between 1991 and 2007.

The researchers used high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet methods to determine participants’ plasma levels of vitamin C and six carotenoids (alphta-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin), which they used to calculate a composite biomarker score.

The recommendation to eat at least five fruits and vegetables a day corresponds to eating ≥400 g/day, according to Dr. Zheng and colleagues. The self-reported median fruit and vegetable intake in the current study was 274, 357, 396, 452, and 508 g/day from lowest to highest quintile.

After multivariable adjustment, higher levels of plasma vitamin C and carotenoids were associated with an 18% and 25% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes per standard deviation, respectively.

Compared with patients whose vitamin C and carotenoid composite biomarker scores were in the lowest 20%, those with scores in the top 20% had half the risk of incident diabetes. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption by 66 g/day was associated with a 25% lower risk of developing diabetes.

“These findings provide strong evidence from objectively measured biomarkers for the recommendation that fruit and vegetable intake should be increased to prevent type 2 diabetes,” according to the researchers.

However, consumption of fruits and vegetables remains far below guideline recommendations, they observed. “Although five portions a day of fruit and vegetables have been recommended for decades, in 2014-2015, 69% of U.K. adults ate fewer than this number, and this proportion is even higher in European adults (86%).”

Dr. Zheng and colleagues acknowledged that study limitations include those that are inherent with observational studies.

Although they could not distinguish between juice, fortified products, or whole foods, the analyses “were adjusted for vitamin supplement use, and suggest that as biomarkers of fruit and vegetable intake these findings endorse the consumption of fruit and vegetables, not that of supplements,” they maintained.

The study by Mr. Hu and colleagues was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The InterAct project was funded by the EU FP6 program. Biomarker measurements for vitamin C and carotenoids were funded by the InterAct project, EPIC-CVD project, MRC Cambridge Initiative, European Commission Framework Program 7, European Research Council, and National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Zheng has reported receiving funding from Westlake University and the EU Horizon 2020 program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pooled analysis of three large prospective American cohorts, people with the highest versus lowest total consumption of whole grain foods had a significantly lower risk of type 2 diabetes.

“These findings provide further support for the current recommendations of increasing whole grain consumption as part of a healthy diet for the prevention of type 2 diabetes,” wrote the authors led by Yang Hu, a doctoral student at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

Similarly, in a large European case-cohort study, people with higher values for plasma vitamin C and carotenoids (fruit and vegetable intake) had a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes.

“This study suggests that even a modest increase in fruit and vegetable intake could help to prevent type 2 diabetes ... regardless of whether the increase is among people with initially low or high intake,” wrote Ju-Sheng Zheng, PhD, University of Cambridge (England), and colleagues.

Individual whole grain foods

Previous studies have shown that high consumption of whole grains is associated with a lower risk of developing chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and some types of cancer, Mr. Hu and colleagues wrote.

Although research has shown that whole grain breakfast cereal and brown rice are linked with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, the effect of other commonly consumed whole grain foods – which contain different amounts of dietary fiber, antioxidants, magnesium, and phytochemicals – has not been established.

Mr. Hu and colleagues analyzed pooled data from 158,259 U.S. women who participated in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017) and 36,525 U.S. men who took part in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986-2016), who were free of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Participants’ baseline consumption of seven types of whole grain foods – whole grain breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, added bran, wheat germ, and popcorn – was based on self-replies to food frequency questionnaires.

During an average 24-year follow-up, 18,629 participants developed type 2 diabetes.

After adjusting for body mass index, lifestyle, and dietary risk factors, participants in the highest quintile of total whole grain consumption had a 29% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes than those in the lowest quintile.

The most commonly consumed whole grain foods were whole grain cold breakfast cereal, dark bread, and popcorn.

Compared with eating less than one serving a month of whole grain cold breakfast cereal or dark bread, eating one or more servings a day was associated with a 19% and 21% lower risk of developing diabetes, respectively.

For popcorn, a J-shaped association was found for intake, where the risk of type 2 diabetes was not significantly raised until consumption exceeded about one serving a day, which led to about an 8% increased risk of developing diabetes – likely related to fat and sugar added to the popcorn, the researchers wrote.

For the less frequently consumed whole grain foods, compared with eating less than one serving a month of oatmeal, brown rice, added bran, or wheat germ, participants who ate two or more servings a week had a 21%, 12%, 15%, and 12% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, respectively.

Lean or overweight individuals had a greater decreased risk of diabetes with increased consumption of whole grain foods; however, because individuals with obesity have a higher risk of diabetes, even a small decrease in risk is still meaningful.

Limitations include the study was observational and may have had unknown confounders, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations, the authors note.

‘Five a day’ fruits and vegetables

Only one previous small published study from the United Kingdom has examined how blood levels of vitamin C and carotenoids are associated with incident type 2 diabetes, Dr. Zheng and colleagues wrote.

They investigated the relationship in 9,754 adults who developed new-onset type 2 diabetes and a comparison group of 13,662 adults who remained diabetes free during an average 9.7-year follow-up, from 340,234 participants in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition–InterAct study.

Participants were from Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, and incident type 2 diabetes occurred between 1991 and 2007.

The researchers used high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet methods to determine participants’ plasma levels of vitamin C and six carotenoids (alphta-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin), which they used to calculate a composite biomarker score.

The recommendation to eat at least five fruits and vegetables a day corresponds to eating ≥400 g/day, according to Dr. Zheng and colleagues. The self-reported median fruit and vegetable intake in the current study was 274, 357, 396, 452, and 508 g/day from lowest to highest quintile.

After multivariable adjustment, higher levels of plasma vitamin C and carotenoids were associated with an 18% and 25% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes per standard deviation, respectively.

Compared with patients whose vitamin C and carotenoid composite biomarker scores were in the lowest 20%, those with scores in the top 20% had half the risk of incident diabetes. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption by 66 g/day was associated with a 25% lower risk of developing diabetes.

“These findings provide strong evidence from objectively measured biomarkers for the recommendation that fruit and vegetable intake should be increased to prevent type 2 diabetes,” according to the researchers.

However, consumption of fruits and vegetables remains far below guideline recommendations, they observed. “Although five portions a day of fruit and vegetables have been recommended for decades, in 2014-2015, 69% of U.K. adults ate fewer than this number, and this proportion is even higher in European adults (86%).”

Dr. Zheng and colleagues acknowledged that study limitations include those that are inherent with observational studies.

Although they could not distinguish between juice, fortified products, or whole foods, the analyses “were adjusted for vitamin supplement use, and suggest that as biomarkers of fruit and vegetable intake these findings endorse the consumption of fruit and vegetables, not that of supplements,” they maintained.

The study by Mr. Hu and colleagues was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The InterAct project was funded by the EU FP6 program. Biomarker measurements for vitamin C and carotenoids were funded by the InterAct project, EPIC-CVD project, MRC Cambridge Initiative, European Commission Framework Program 7, European Research Council, and National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Zheng has reported receiving funding from Westlake University and the EU Horizon 2020 program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pooled analysis of three large prospective American cohorts, people with the highest versus lowest total consumption of whole grain foods had a significantly lower risk of type 2 diabetes.

“These findings provide further support for the current recommendations of increasing whole grain consumption as part of a healthy diet for the prevention of type 2 diabetes,” wrote the authors led by Yang Hu, a doctoral student at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

Similarly, in a large European case-cohort study, people with higher values for plasma vitamin C and carotenoids (fruit and vegetable intake) had a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes.

“This study suggests that even a modest increase in fruit and vegetable intake could help to prevent type 2 diabetes ... regardless of whether the increase is among people with initially low or high intake,” wrote Ju-Sheng Zheng, PhD, University of Cambridge (England), and colleagues.

Individual whole grain foods

Previous studies have shown that high consumption of whole grains is associated with a lower risk of developing chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and some types of cancer, Mr. Hu and colleagues wrote.

Although research has shown that whole grain breakfast cereal and brown rice are linked with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, the effect of other commonly consumed whole grain foods – which contain different amounts of dietary fiber, antioxidants, magnesium, and phytochemicals – has not been established.

Mr. Hu and colleagues analyzed pooled data from 158,259 U.S. women who participated in the Nurses’ Health Study (1984-2014) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991-2017) and 36,525 U.S. men who took part in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986-2016), who were free of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Participants’ baseline consumption of seven types of whole grain foods – whole grain breakfast cereal, oatmeal, dark bread, brown rice, added bran, wheat germ, and popcorn – was based on self-replies to food frequency questionnaires.

During an average 24-year follow-up, 18,629 participants developed type 2 diabetes.

After adjusting for body mass index, lifestyle, and dietary risk factors, participants in the highest quintile of total whole grain consumption had a 29% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes than those in the lowest quintile.

The most commonly consumed whole grain foods were whole grain cold breakfast cereal, dark bread, and popcorn.

Compared with eating less than one serving a month of whole grain cold breakfast cereal or dark bread, eating one or more servings a day was associated with a 19% and 21% lower risk of developing diabetes, respectively.

For popcorn, a J-shaped association was found for intake, where the risk of type 2 diabetes was not significantly raised until consumption exceeded about one serving a day, which led to about an 8% increased risk of developing diabetes – likely related to fat and sugar added to the popcorn, the researchers wrote.

For the less frequently consumed whole grain foods, compared with eating less than one serving a month of oatmeal, brown rice, added bran, or wheat germ, participants who ate two or more servings a week had a 21%, 12%, 15%, and 12% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, respectively.

Lean or overweight individuals had a greater decreased risk of diabetes with increased consumption of whole grain foods; however, because individuals with obesity have a higher risk of diabetes, even a small decrease in risk is still meaningful.

Limitations include the study was observational and may have had unknown confounders, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations, the authors note.

‘Five a day’ fruits and vegetables

Only one previous small published study from the United Kingdom has examined how blood levels of vitamin C and carotenoids are associated with incident type 2 diabetes, Dr. Zheng and colleagues wrote.

They investigated the relationship in 9,754 adults who developed new-onset type 2 diabetes and a comparison group of 13,662 adults who remained diabetes free during an average 9.7-year follow-up, from 340,234 participants in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition–InterAct study.

Participants were from Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, and incident type 2 diabetes occurred between 1991 and 2007.

The researchers used high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet methods to determine participants’ plasma levels of vitamin C and six carotenoids (alphta-carotene, beta-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin), which they used to calculate a composite biomarker score.

The recommendation to eat at least five fruits and vegetables a day corresponds to eating ≥400 g/day, according to Dr. Zheng and colleagues. The self-reported median fruit and vegetable intake in the current study was 274, 357, 396, 452, and 508 g/day from lowest to highest quintile.

After multivariable adjustment, higher levels of plasma vitamin C and carotenoids were associated with an 18% and 25% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes per standard deviation, respectively.

Compared with patients whose vitamin C and carotenoid composite biomarker scores were in the lowest 20%, those with scores in the top 20% had half the risk of incident diabetes. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption by 66 g/day was associated with a 25% lower risk of developing diabetes.

“These findings provide strong evidence from objectively measured biomarkers for the recommendation that fruit and vegetable intake should be increased to prevent type 2 diabetes,” according to the researchers.

However, consumption of fruits and vegetables remains far below guideline recommendations, they observed. “Although five portions a day of fruit and vegetables have been recommended for decades, in 2014-2015, 69% of U.K. adults ate fewer than this number, and this proportion is even higher in European adults (86%).”

Dr. Zheng and colleagues acknowledged that study limitations include those that are inherent with observational studies.

Although they could not distinguish between juice, fortified products, or whole foods, the analyses “were adjusted for vitamin supplement use, and suggest that as biomarkers of fruit and vegetable intake these findings endorse the consumption of fruit and vegetables, not that of supplements,” they maintained.

The study by Mr. Hu and colleagues was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The InterAct project was funded by the EU FP6 program. Biomarker measurements for vitamin C and carotenoids were funded by the InterAct project, EPIC-CVD project, MRC Cambridge Initiative, European Commission Framework Program 7, European Research Council, and National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Zheng has reported receiving funding from Westlake University and the EU Horizon 2020 program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intermittent fasting ‘not benign’ for patients with diabetes

stress the authors of a new viewpoint published online July 2 in JAMA.

This is because intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes has only been studied in seven small, short published trials of very different regimens, with limited evidence of benefit. In addition, some concerns arose from these studies.

Weight loss with intermittent fasting appears to be similar to that attained with caloric restriction, but in the case of those with diabetes, the best way to adjust glucose-lowering medicines to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia while practicing intermittent fasting has not been established, and there is potential for such fasting to cause glycemic variability.

The viewpoint’s lead author Benjamin D. Horne, PhD, MStat, MPH, from Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, and Stanford (Calif.) University, expanded on the issues in a podcast interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard C. Bauchner, MD.

Asked if he would advise intermittent fasting for patients with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Horne replied that he would recommend it, with caveats, “because of the safety issues – some of which are fairly benign for people who are apparently healthy but may be not quite as benign for people with type 2 diabetes.

“Things such as low blood pressure, weakness, headaches, [and] dizziness are considerations,” he continued, but “the big issue” is hypoglycemia, so caloric restriction may be a better choice for some patients with diabetes.

Dr. Horne said he likes to give patients options. “I’ve met quite a number of people who are very behind time-restricted feeding – eating during a 6- to 8-hour window,” he said. “If they are able to stay on it, they tend to really love it.”

The most popular regimen that results in some weight loss is fasting for 24 hours – with or without a 500-calorie meal – on 2 nonconsecutive days a week, the so-called 5:2 diet. And “as someone who’s in cardiovascular research,” Dr. Horne added, “the one that I’m thinking for long term is once-a-week fasting for a 24-hour period.”

Intermittent fasting: Less safe than calorie restriction in diabetes?

Patients who already have diabetes and lose weight benefit from improved glucose, blood pressure, and lipid levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues wrote.

Currently, intermittent fasting is popular in the lay press and on social media with claims of potential benefits for diabetes “that are as yet untested or unproven,” they added. In fact, “whether a patient with type 2 diabetes should engage in intermittent fasting involves a variety of concerns over safety and efficacy.”

Thus, they examined the existing evidence for the health effects and safety of intermittent fasting – defined as time-restricted feeding, or fasting on alternate days or during 1-4 days a week, with only water or also juice and bone broth, or no more than 700 calories allowed on fasting days – in patients with type 2 diabetes.

They found seven published studies of intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes, including five randomized clinical trials, of which only one study had more than 63 patients.

Intermittent fasting regimens in the studies included five fasting frequencies and most follow-up durations were 4 months or less, including 18-20 hours a day for 2 weeks; 2 days a week for 12 weeks (two studies) or for 12 months (one study); 3-4 days a week for 7-11 months; 4 days a week for 12 weeks; and 17 days in 4 months.

They all reported that intermittent fasting was tied to weight loss, and most (but not all) of the studies also found that it was associated with decreases in A1c and improved glucose levels, quality of life, and blood pressure, but not insulin resistance.

But this “heterogeneity of designs and regimens and the variance in results make it difficult to draw clinically meaningful direction,” Dr. Horne and colleagues observed.

Moreover, only one study addressed the relative safety of two intermittent fasting regimens, and it found that both regimens increased hypoglycemic events despite the use of a medication dose-change protocol.

Only one study explicitly compared intermittent fasting with caloric restriction, which found “that a twice-weekly intermittent fasting regimen improved [A1c] levels is promising,” the authors wrote.

However, that study showed only noninferiority for change in A1c level (–0.3% for intermittent fasting vs. –0.5% for caloric restriction).

The major implication, according to the viewpoint authors, is that “intermittent fasting may be less safe than caloric restriction although approximately equivalently effective.”

“Therefore,” they summarized, “until intermittent fasting is shown to be more effective than caloric restriction for reducing [A1c] or otherwise controlling diabetes, that study – and the limited other high-quality data – suggest that intermittent fasting regimens for patients with type 2 diabetes recommended by health professionals or promoted to the public should be limited to individuals for whom the risk of hypoglycemia is closely monitored and medications are carefully adjusted to ensure safety.”

Should continuous glucose monitoring to detect glycemic variability be considered?

Intermittent fasting may also bring wider fluctuations of glycemic control than simple calorie restriction, with hypoglycemia during fasting times and hyperglycemia during feeding times, which would not be reflected in A1c levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues pointed out.

“Studies have raised concern that glycemic variability leads to both microvascular (e.g., retinopathy) and macrovascular (e.g., coronary disease) complications in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they cautioned.

Therefore, “continuous glucose monitoring should be considered for studies of ... clinical interventions using intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they concluded.

Dr. Horne has reported serving as principal investigator of grants for studies on intermittent fasting from the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation. Disclosures of the other two authors are listed with the viewpoint.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

stress the authors of a new viewpoint published online July 2 in JAMA.

This is because intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes has only been studied in seven small, short published trials of very different regimens, with limited evidence of benefit. In addition, some concerns arose from these studies.

Weight loss with intermittent fasting appears to be similar to that attained with caloric restriction, but in the case of those with diabetes, the best way to adjust glucose-lowering medicines to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia while practicing intermittent fasting has not been established, and there is potential for such fasting to cause glycemic variability.

The viewpoint’s lead author Benjamin D. Horne, PhD, MStat, MPH, from Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, and Stanford (Calif.) University, expanded on the issues in a podcast interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard C. Bauchner, MD.

Asked if he would advise intermittent fasting for patients with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Horne replied that he would recommend it, with caveats, “because of the safety issues – some of which are fairly benign for people who are apparently healthy but may be not quite as benign for people with type 2 diabetes.

“Things such as low blood pressure, weakness, headaches, [and] dizziness are considerations,” he continued, but “the big issue” is hypoglycemia, so caloric restriction may be a better choice for some patients with diabetes.

Dr. Horne said he likes to give patients options. “I’ve met quite a number of people who are very behind time-restricted feeding – eating during a 6- to 8-hour window,” he said. “If they are able to stay on it, they tend to really love it.”

The most popular regimen that results in some weight loss is fasting for 24 hours – with or without a 500-calorie meal – on 2 nonconsecutive days a week, the so-called 5:2 diet. And “as someone who’s in cardiovascular research,” Dr. Horne added, “the one that I’m thinking for long term is once-a-week fasting for a 24-hour period.”

Intermittent fasting: Less safe than calorie restriction in diabetes?

Patients who already have diabetes and lose weight benefit from improved glucose, blood pressure, and lipid levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues wrote.

Currently, intermittent fasting is popular in the lay press and on social media with claims of potential benefits for diabetes “that are as yet untested or unproven,” they added. In fact, “whether a patient with type 2 diabetes should engage in intermittent fasting involves a variety of concerns over safety and efficacy.”

Thus, they examined the existing evidence for the health effects and safety of intermittent fasting – defined as time-restricted feeding, or fasting on alternate days or during 1-4 days a week, with only water or also juice and bone broth, or no more than 700 calories allowed on fasting days – in patients with type 2 diabetes.

They found seven published studies of intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes, including five randomized clinical trials, of which only one study had more than 63 patients.

Intermittent fasting regimens in the studies included five fasting frequencies and most follow-up durations were 4 months or less, including 18-20 hours a day for 2 weeks; 2 days a week for 12 weeks (two studies) or for 12 months (one study); 3-4 days a week for 7-11 months; 4 days a week for 12 weeks; and 17 days in 4 months.

They all reported that intermittent fasting was tied to weight loss, and most (but not all) of the studies also found that it was associated with decreases in A1c and improved glucose levels, quality of life, and blood pressure, but not insulin resistance.

But this “heterogeneity of designs and regimens and the variance in results make it difficult to draw clinically meaningful direction,” Dr. Horne and colleagues observed.

Moreover, only one study addressed the relative safety of two intermittent fasting regimens, and it found that both regimens increased hypoglycemic events despite the use of a medication dose-change protocol.

Only one study explicitly compared intermittent fasting with caloric restriction, which found “that a twice-weekly intermittent fasting regimen improved [A1c] levels is promising,” the authors wrote.

However, that study showed only noninferiority for change in A1c level (–0.3% for intermittent fasting vs. –0.5% for caloric restriction).

The major implication, according to the viewpoint authors, is that “intermittent fasting may be less safe than caloric restriction although approximately equivalently effective.”

“Therefore,” they summarized, “until intermittent fasting is shown to be more effective than caloric restriction for reducing [A1c] or otherwise controlling diabetes, that study – and the limited other high-quality data – suggest that intermittent fasting regimens for patients with type 2 diabetes recommended by health professionals or promoted to the public should be limited to individuals for whom the risk of hypoglycemia is closely monitored and medications are carefully adjusted to ensure safety.”

Should continuous glucose monitoring to detect glycemic variability be considered?

Intermittent fasting may also bring wider fluctuations of glycemic control than simple calorie restriction, with hypoglycemia during fasting times and hyperglycemia during feeding times, which would not be reflected in A1c levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues pointed out.

“Studies have raised concern that glycemic variability leads to both microvascular (e.g., retinopathy) and macrovascular (e.g., coronary disease) complications in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they cautioned.

Therefore, “continuous glucose monitoring should be considered for studies of ... clinical interventions using intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they concluded.

Dr. Horne has reported serving as principal investigator of grants for studies on intermittent fasting from the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation. Disclosures of the other two authors are listed with the viewpoint.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

stress the authors of a new viewpoint published online July 2 in JAMA.

This is because intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes has only been studied in seven small, short published trials of very different regimens, with limited evidence of benefit. In addition, some concerns arose from these studies.

Weight loss with intermittent fasting appears to be similar to that attained with caloric restriction, but in the case of those with diabetes, the best way to adjust glucose-lowering medicines to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia while practicing intermittent fasting has not been established, and there is potential for such fasting to cause glycemic variability.

The viewpoint’s lead author Benjamin D. Horne, PhD, MStat, MPH, from Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, and Stanford (Calif.) University, expanded on the issues in a podcast interview with JAMA editor in chief Howard C. Bauchner, MD.

Asked if he would advise intermittent fasting for patients with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Horne replied that he would recommend it, with caveats, “because of the safety issues – some of which are fairly benign for people who are apparently healthy but may be not quite as benign for people with type 2 diabetes.

“Things such as low blood pressure, weakness, headaches, [and] dizziness are considerations,” he continued, but “the big issue” is hypoglycemia, so caloric restriction may be a better choice for some patients with diabetes.

Dr. Horne said he likes to give patients options. “I’ve met quite a number of people who are very behind time-restricted feeding – eating during a 6- to 8-hour window,” he said. “If they are able to stay on it, they tend to really love it.”

The most popular regimen that results in some weight loss is fasting for 24 hours – with or without a 500-calorie meal – on 2 nonconsecutive days a week, the so-called 5:2 diet. And “as someone who’s in cardiovascular research,” Dr. Horne added, “the one that I’m thinking for long term is once-a-week fasting for a 24-hour period.”

Intermittent fasting: Less safe than calorie restriction in diabetes?

Patients who already have diabetes and lose weight benefit from improved glucose, blood pressure, and lipid levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues wrote.

Currently, intermittent fasting is popular in the lay press and on social media with claims of potential benefits for diabetes “that are as yet untested or unproven,” they added. In fact, “whether a patient with type 2 diabetes should engage in intermittent fasting involves a variety of concerns over safety and efficacy.”

Thus, they examined the existing evidence for the health effects and safety of intermittent fasting – defined as time-restricted feeding, or fasting on alternate days or during 1-4 days a week, with only water or also juice and bone broth, or no more than 700 calories allowed on fasting days – in patients with type 2 diabetes.

They found seven published studies of intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes, including five randomized clinical trials, of which only one study had more than 63 patients.

Intermittent fasting regimens in the studies included five fasting frequencies and most follow-up durations were 4 months or less, including 18-20 hours a day for 2 weeks; 2 days a week for 12 weeks (two studies) or for 12 months (one study); 3-4 days a week for 7-11 months; 4 days a week for 12 weeks; and 17 days in 4 months.

They all reported that intermittent fasting was tied to weight loss, and most (but not all) of the studies also found that it was associated with decreases in A1c and improved glucose levels, quality of life, and blood pressure, but not insulin resistance.

But this “heterogeneity of designs and regimens and the variance in results make it difficult to draw clinically meaningful direction,” Dr. Horne and colleagues observed.

Moreover, only one study addressed the relative safety of two intermittent fasting regimens, and it found that both regimens increased hypoglycemic events despite the use of a medication dose-change protocol.

Only one study explicitly compared intermittent fasting with caloric restriction, which found “that a twice-weekly intermittent fasting regimen improved [A1c] levels is promising,” the authors wrote.

However, that study showed only noninferiority for change in A1c level (–0.3% for intermittent fasting vs. –0.5% for caloric restriction).

The major implication, according to the viewpoint authors, is that “intermittent fasting may be less safe than caloric restriction although approximately equivalently effective.”

“Therefore,” they summarized, “until intermittent fasting is shown to be more effective than caloric restriction for reducing [A1c] or otherwise controlling diabetes, that study – and the limited other high-quality data – suggest that intermittent fasting regimens for patients with type 2 diabetes recommended by health professionals or promoted to the public should be limited to individuals for whom the risk of hypoglycemia is closely monitored and medications are carefully adjusted to ensure safety.”

Should continuous glucose monitoring to detect glycemic variability be considered?

Intermittent fasting may also bring wider fluctuations of glycemic control than simple calorie restriction, with hypoglycemia during fasting times and hyperglycemia during feeding times, which would not be reflected in A1c levels, Dr. Horne and colleagues pointed out.

“Studies have raised concern that glycemic variability leads to both microvascular (e.g., retinopathy) and macrovascular (e.g., coronary disease) complications in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they cautioned.

Therefore, “continuous glucose monitoring should be considered for studies of ... clinical interventions using intermittent fasting in patients with type 2 diabetes,” they concluded.

Dr. Horne has reported serving as principal investigator of grants for studies on intermittent fasting from the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation. Disclosures of the other two authors are listed with the viewpoint.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Lipid-lowering bempedoic acid does not hasten or worsen diabetes

In an analysis of four phase 3 trials, the oral lipid-lowering drug bempedoic acid (Nexletol; Esperion) did not worsen glycemic control or increase the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

As previously reported, this first-in-class drug, which acts by inhibiting ATP-citrate lyase, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2020.

Lawrence A. Leiter MD, from the University of Toronto, delivered the findings of this latest analysis in an oral presentation at the virtual American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions.

“The current study is important as it shows overall consistent efficacy and safety regardless of glycemic status and no increase in new-onset diabetes,” Dr. Leiter said in an interview.

There is interest in how lipid-lowering drugs might affect glycemia because “meta-analyses have shown about a 10% increased risk of new-onset diabetes in statin users, although the absolute increased risk is 1 extra case per 255 treated patients [in whom one would expect 5.4 cardiovascular events to be prevented by the statin],” he noted.

In a comment, John R. Guyton, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed that the new study demonstrates that “patients with diabetes and prediabetes respond to bempedoic acid with LDL cholesterol lowering that is similar to that in patients with normal glucose tolerance.”

Although “statins have a slight effect of worsening glucose tolerance and a modest effect of increasing cases of new-onset diabetes,” the current research shows that “bempedoic acid appears to be free of these effects,” said Dr. Guyton, who discussed this drug in another symposium at the meeting where he also discussed how the agent will “fit” into prescribing patterns.

How do patients with diabetes, prediabetes fare?

“Current guidelines support aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering in patients with diabetes, given the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Leiter.

Bempedoic acid was approved as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy to treat adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) who require additional lowering of LDL cholesterol, although its effect on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been determined, the prescribing information states.

However, it has been unknown how bempedoic acid affects LDL cholesterol or hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.

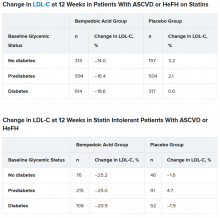

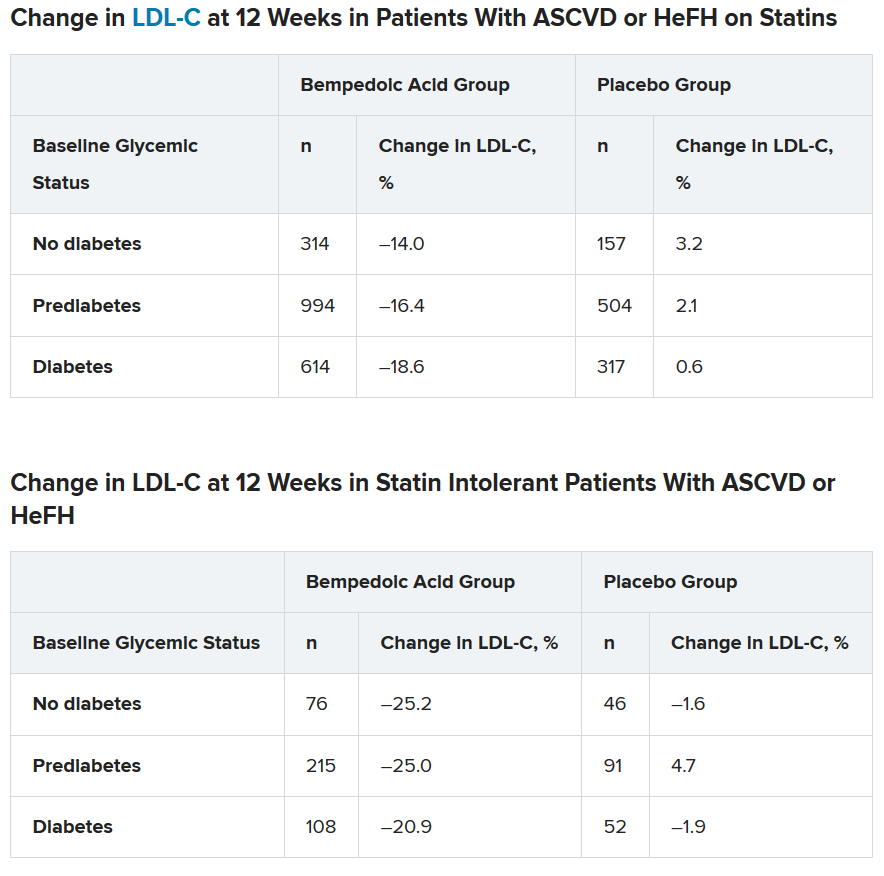

To examine this, the researchers pooled data from four phase 3 trials in 3623 patients with ASCVD or HeFH who had been randomized 2:1 to bempedoic acid 180 mg/day or placebo for 12 or 24 weeks (if they were statin intolerant) or 52 weeks (if they were also on statins).

In the pooled sample, about half the patients had prediabetes (52%), and the rest had diabetes (31%) or normoglycemia (17%). Overall, 75%-84% of patients had a history of ASCVD.

Mean LDL cholesterol levels were higher in patients with normoglycemia (119 mg/dL) or prediabetes (115 mg/dL) than in patients with diabetes (110 mg/dL).

The primary outcome was percent change in LDL cholesterol from baseline to week 12.

In the two types of patients (all with ASCVD or HeFH) – those on statins and those with statin intolerance – LDL cholesterol at 12 weeks was significantly lower in patients who received bempedoic acid, compared with placebo, regardless of whether they had no diabetes, prediabetes, or diabetes (all P < .001).

Similarly, patients who received bempedoic acid also had significant reductions in total cholesterol, non–HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) at 12 weeks, compared with patients who received placebo (all P < .01).

The safety profile of bempedoic acid was similar to placebo and did not vary by glycemic status.

“Of course, with any lipid-lowering therapy, there’s lots of interest in changes in glycemic parameters,” said Dr. Leiter. “A1c did not increase. In fact, it was significantly lower in patients with prediabetes and diabetes on bempedoic acid versus placebo.”

In addition, “statin trials have shown small increases in body weight. We did not observe this,” he reported.

Where does bempedoic acid ‘fit?’

“Bempedoic acid will be a useful add-on to any patient who requires additional LDL cholesterol lowering,” according to Dr. Leiter. “It will typically be used as an add-on to statins, but will also be very useful in the statin-intolerant patient, especially when used in combination with ezetimib.”

The fixed-dose combination of bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe (Nexlizet; Esperion), was also approved in the United States in February, just days after bempedoic acid as a solo agent was cleared for marketing.

“Bempedoic acid would not be chosen in preference to a statin, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitor,” Dr. Guyton said. Rather, “its chief use will be in patients with statin intolerance and either FH or ASCVD when LDL-cholesterol is poorly controlled despite maximum tolerated lipid-lowering therapy.”

According to Dr. Guyton, “use of bempedoic acid should be undertaken only when provider-patient discussion acknowledges that it has not been shown to reduce cardiovascular events, although preliminary evidence from genetic analysis [Mendelian randomization study] suggests that it will,” as previously reported.

The CLEAR Outcomes cardiovascular outcomes trial of bempedoic acid completed enrollment in August 2019, involving 14,032 patients with hypercholesterolemia and high CVD risk according to a company statement.

The study was funded by Esperion. Dr. Leiter has reported being on advisory panels for Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier, receiving research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, and the Medicines Company, and being on speakers bureaus for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the abstract. Dr. Guyton has reported being a consultant for Amarin and receiving research support form Regeneron.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In an analysis of four phase 3 trials, the oral lipid-lowering drug bempedoic acid (Nexletol; Esperion) did not worsen glycemic control or increase the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

As previously reported, this first-in-class drug, which acts by inhibiting ATP-citrate lyase, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2020.

Lawrence A. Leiter MD, from the University of Toronto, delivered the findings of this latest analysis in an oral presentation at the virtual American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions.

“The current study is important as it shows overall consistent efficacy and safety regardless of glycemic status and no increase in new-onset diabetes,” Dr. Leiter said in an interview.

There is interest in how lipid-lowering drugs might affect glycemia because “meta-analyses have shown about a 10% increased risk of new-onset diabetes in statin users, although the absolute increased risk is 1 extra case per 255 treated patients [in whom one would expect 5.4 cardiovascular events to be prevented by the statin],” he noted.

In a comment, John R. Guyton, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed that the new study demonstrates that “patients with diabetes and prediabetes respond to bempedoic acid with LDL cholesterol lowering that is similar to that in patients with normal glucose tolerance.”

Although “statins have a slight effect of worsening glucose tolerance and a modest effect of increasing cases of new-onset diabetes,” the current research shows that “bempedoic acid appears to be free of these effects,” said Dr. Guyton, who discussed this drug in another symposium at the meeting where he also discussed how the agent will “fit” into prescribing patterns.

How do patients with diabetes, prediabetes fare?

“Current guidelines support aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering in patients with diabetes, given the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Leiter.

Bempedoic acid was approved as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy to treat adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) who require additional lowering of LDL cholesterol, although its effect on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been determined, the prescribing information states.

However, it has been unknown how bempedoic acid affects LDL cholesterol or hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.

To examine this, the researchers pooled data from four phase 3 trials in 3623 patients with ASCVD or HeFH who had been randomized 2:1 to bempedoic acid 180 mg/day or placebo for 12 or 24 weeks (if they were statin intolerant) or 52 weeks (if they were also on statins).

In the pooled sample, about half the patients had prediabetes (52%), and the rest had diabetes (31%) or normoglycemia (17%). Overall, 75%-84% of patients had a history of ASCVD.

Mean LDL cholesterol levels were higher in patients with normoglycemia (119 mg/dL) or prediabetes (115 mg/dL) than in patients with diabetes (110 mg/dL).

The primary outcome was percent change in LDL cholesterol from baseline to week 12.

In the two types of patients (all with ASCVD or HeFH) – those on statins and those with statin intolerance – LDL cholesterol at 12 weeks was significantly lower in patients who received bempedoic acid, compared with placebo, regardless of whether they had no diabetes, prediabetes, or diabetes (all P < .001).

Similarly, patients who received bempedoic acid also had significant reductions in total cholesterol, non–HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) at 12 weeks, compared with patients who received placebo (all P < .01).

The safety profile of bempedoic acid was similar to placebo and did not vary by glycemic status.

“Of course, with any lipid-lowering therapy, there’s lots of interest in changes in glycemic parameters,” said Dr. Leiter. “A1c did not increase. In fact, it was significantly lower in patients with prediabetes and diabetes on bempedoic acid versus placebo.”

In addition, “statin trials have shown small increases in body weight. We did not observe this,” he reported.

Where does bempedoic acid ‘fit?’

“Bempedoic acid will be a useful add-on to any patient who requires additional LDL cholesterol lowering,” according to Dr. Leiter. “It will typically be used as an add-on to statins, but will also be very useful in the statin-intolerant patient, especially when used in combination with ezetimib.”

The fixed-dose combination of bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe (Nexlizet; Esperion), was also approved in the United States in February, just days after bempedoic acid as a solo agent was cleared for marketing.

“Bempedoic acid would not be chosen in preference to a statin, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitor,” Dr. Guyton said. Rather, “its chief use will be in patients with statin intolerance and either FH or ASCVD when LDL-cholesterol is poorly controlled despite maximum tolerated lipid-lowering therapy.”

According to Dr. Guyton, “use of bempedoic acid should be undertaken only when provider-patient discussion acknowledges that it has not been shown to reduce cardiovascular events, although preliminary evidence from genetic analysis [Mendelian randomization study] suggests that it will,” as previously reported.

The CLEAR Outcomes cardiovascular outcomes trial of bempedoic acid completed enrollment in August 2019, involving 14,032 patients with hypercholesterolemia and high CVD risk according to a company statement.

The study was funded by Esperion. Dr. Leiter has reported being on advisory panels for Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier, receiving research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, and the Medicines Company, and being on speakers bureaus for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the abstract. Dr. Guyton has reported being a consultant for Amarin and receiving research support form Regeneron.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In an analysis of four phase 3 trials, the oral lipid-lowering drug bempedoic acid (Nexletol; Esperion) did not worsen glycemic control or increase the incidence of type 2 diabetes.

As previously reported, this first-in-class drug, which acts by inhibiting ATP-citrate lyase, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2020.

Lawrence A. Leiter MD, from the University of Toronto, delivered the findings of this latest analysis in an oral presentation at the virtual American Diabetes Association 80th Scientific Sessions.

“The current study is important as it shows overall consistent efficacy and safety regardless of glycemic status and no increase in new-onset diabetes,” Dr. Leiter said in an interview.

There is interest in how lipid-lowering drugs might affect glycemia because “meta-analyses have shown about a 10% increased risk of new-onset diabetes in statin users, although the absolute increased risk is 1 extra case per 255 treated patients [in whom one would expect 5.4 cardiovascular events to be prevented by the statin],” he noted.

In a comment, John R. Guyton, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., agreed that the new study demonstrates that “patients with diabetes and prediabetes respond to bempedoic acid with LDL cholesterol lowering that is similar to that in patients with normal glucose tolerance.”

Although “statins have a slight effect of worsening glucose tolerance and a modest effect of increasing cases of new-onset diabetes,” the current research shows that “bempedoic acid appears to be free of these effects,” said Dr. Guyton, who discussed this drug in another symposium at the meeting where he also discussed how the agent will “fit” into prescribing patterns.

How do patients with diabetes, prediabetes fare?

“Current guidelines support aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering in patients with diabetes, given the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Leiter.

Bempedoic acid was approved as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy to treat adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) who require additional lowering of LDL cholesterol, although its effect on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been determined, the prescribing information states.

However, it has been unknown how bempedoic acid affects LDL cholesterol or hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.

To examine this, the researchers pooled data from four phase 3 trials in 3623 patients with ASCVD or HeFH who had been randomized 2:1 to bempedoic acid 180 mg/day or placebo for 12 or 24 weeks (if they were statin intolerant) or 52 weeks (if they were also on statins).

In the pooled sample, about half the patients had prediabetes (52%), and the rest had diabetes (31%) or normoglycemia (17%). Overall, 75%-84% of patients had a history of ASCVD.

Mean LDL cholesterol levels were higher in patients with normoglycemia (119 mg/dL) or prediabetes (115 mg/dL) than in patients with diabetes (110 mg/dL).

The primary outcome was percent change in LDL cholesterol from baseline to week 12.

In the two types of patients (all with ASCVD or HeFH) – those on statins and those with statin intolerance – LDL cholesterol at 12 weeks was significantly lower in patients who received bempedoic acid, compared with placebo, regardless of whether they had no diabetes, prediabetes, or diabetes (all P < .001).

Similarly, patients who received bempedoic acid also had significant reductions in total cholesterol, non–HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) at 12 weeks, compared with patients who received placebo (all P < .01).

The safety profile of bempedoic acid was similar to placebo and did not vary by glycemic status.

“Of course, with any lipid-lowering therapy, there’s lots of interest in changes in glycemic parameters,” said Dr. Leiter. “A1c did not increase. In fact, it was significantly lower in patients with prediabetes and diabetes on bempedoic acid versus placebo.”

In addition, “statin trials have shown small increases in body weight. We did not observe this,” he reported.

Where does bempedoic acid ‘fit?’

“Bempedoic acid will be a useful add-on to any patient who requires additional LDL cholesterol lowering,” according to Dr. Leiter. “It will typically be used as an add-on to statins, but will also be very useful in the statin-intolerant patient, especially when used in combination with ezetimib.”

The fixed-dose combination of bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe (Nexlizet; Esperion), was also approved in the United States in February, just days after bempedoic acid as a solo agent was cleared for marketing.

“Bempedoic acid would not be chosen in preference to a statin, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitor,” Dr. Guyton said. Rather, “its chief use will be in patients with statin intolerance and either FH or ASCVD when LDL-cholesterol is poorly controlled despite maximum tolerated lipid-lowering therapy.”

According to Dr. Guyton, “use of bempedoic acid should be undertaken only when provider-patient discussion acknowledges that it has not been shown to reduce cardiovascular events, although preliminary evidence from genetic analysis [Mendelian randomization study] suggests that it will,” as previously reported.

The CLEAR Outcomes cardiovascular outcomes trial of bempedoic acid completed enrollment in August 2019, involving 14,032 patients with hypercholesterolemia and high CVD risk according to a company statement.

The study was funded by Esperion. Dr. Leiter has reported being on advisory panels for Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier, receiving research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Kowa Pharmaceuticals, and the Medicines Company, and being on speakers bureaus for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, HLS Therapeutics, Janssen, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier. Disclosures for the other authors are listed with the abstract. Dr. Guyton has reported being a consultant for Amarin and receiving research support form Regeneron.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

CV outcomes of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists compared in real-world study

Drug adherence, healthcare use, medical costs, and heart failure rates were better among patients with type 2 diabetes who were newly prescribed a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in a real-world, observational study.

Composite cardiovascular (CV) outcomes were similar between the two drug classes.

Insiya Poonawalla, PhD, a researcher at Humana Healthcare Research, Flower Mound, Texas, reported the study results in an oral presentation on June 12 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 80th Scientific Sessions.

The investigators matched more than 10,000 patients with type 2 diabetes — half initiated on an SGLT2 inhibitor and half initiated on a GLP-1 agonist — from the Humana database of insurance claims data.

“These findings suggest potential benefits” of SGLT2 inhibitors, “particularly where risk related to heart failure is an important consideration,” Poonawalla said, but as always, any benefits need to be weighed against any risks.

And “while this study provides a pretty complete and current picture of claims until 2018,” it has limitations inherent to observational data (such as possible errors or omissions in the claims data), she conceded.

Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, invited to comment on the research, said this preliminary study was likely too short and small to definitively demonstrate differences in composite CV outcomes between the two drug classes, but he noted that the overall findings are not unexpected.

And often, the particular CV risk profile of an individual patient will point to one or the other of these drug classes as a best fit, he noted.

Too soon to alter clinical practice

Kosiborod, from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, said he nevertheless feels “it would be a bit premature to use these findings as a guide to change clinical practice.”

“The study is relatively small in scope and likely underpowered to examine CV outcomes,” he said in an email interview.

Larger population-based studies and ideally head-to-head randomized controlled trials of various type 2 diabetes agents could compare these two drug classes more definitively, he asserted.

In the meantime, safety profiles of both medication classes “have been well established — in tens of thousands of patients in clinical trials and millions of patients prescribed these therapies in clinical practice,” he noted.

In general, the drugs in both classes are well-tolerated and safe for most patients with type 2 diabetes when used appropriately.

“Certainly, patients with type 2 diabetes and established CV disease (or at high risk for CV complications) are ideal candidates for either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 receptor agonist,” Kosiborod said.

“Given the data we have from outcome trials, an SGLT2 inhibitor would be a better initial strategy in a patient with type 2 diabetes and heart failure (especially heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and/or diabetic kidney disease,” he continued.

On the other hand, “a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be a better initial strategy in a type 2 diabetes patient with (or at very high risk for) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), especially if there is concomitant obesity contributing to the disease process.”

Limited comparisons of these two newer drug classes

“Real-world evidence comparing these two therapeutic classes based on CV outcomes is limited,” Poonawalla said at the start of her presentation, and relative treatment persistence, utilization, and cost data are even less well studied.

To investigate this, the researchers identified patients aged 19 to 89 years who were newly prescribed one of these two types of antidiabetic agents during January 1, 2015 through June 30, 2017.

Poonawalla and senior study author Phil Schwab, PhD, research lead, Humana Healthcare Research, Louisville, Kentucky, clarified the study design and findings in an email to this new organization.

The team matched 5507 patients initiated on a GLP-1 agonist with 5507 patients newly prescribed an SGLT2 inhibitor.

Patients were a mean age of 65 years and 53% were women.

More than a third (37%) had established ASCVD, including myocardial infarction (MI) (7.9%) and stroke (9.8%), and 11.5% had heart failure.

About two thirds were receiving metformin and about a third were receiving insulin.

In the GLP-1 agonist group, more than half of patients were prescribed liraglutide (57%), followed by dulaglutide (33%), exenatide, and lixisenatide (two patients).

In the SGLT2 inhibitor group, close to 70% received canagliflozin, about a quarter received empagliflozin, and the rest received dapagliflozin.

During up to 3.5 years of follow-up, a similar percentage of patients in each group had either an MI, stroke, or died (the primary composite CV outcome) (hazard ratio [HR], 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89 - 1.07).

However, more patients in the GLP-1 agonist group had heart failure or died (the secondary composite CV outcome), driven by a higher rate of heart failure in this group.

But after adjusting for time to events there was no significant between-group difference in the secondary composite CV outcome (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99 - 1.21).

During the 12-months after the initial prescription, patients who were started on a GLP-1 agonist versus an SGLT2 inhibitor had higher mean monthly medical costs, which included hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient visits ($904 vs $834; P < .001).

They also had higher pharmacy costs, which covered all drugs ($891 vs $783; P < .001).

And they were more likely to discontinue treatment (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10 - 1.21), be hospitalized (14.4% vs 11.9%; P < .001), or visit the ED (27.4% vs 23.5%; P < .001).

“Not too surprising” and “somewhat reassuring”

Overall, Kosiborod did not find the results surprising.

Given the sample size and follow-up time, event rates were probably quite low and insufficient to draw firm conclusions about the composite CV outcomes, he reiterated.

However, given the comparable effects of these two drug types on major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in similar patient populations with type 2 diabetes, it is not too surprising that there were no significant differences in these outcomes.

It was also “somewhat reassuring” to see that heart failure rates were lower with SGLT2 inhibitors, “as one would expect,” he said, because these agents “have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure in multiple outcome trials, whereas GLP-1 receptor agonists’ beneficial CV effects appear to be more limited to MACE reduction.”

The higher rates of discontinuation with GLP-1 receptor agonists “is also not a surprise, since patients experience more gastrointestinal tolerability issues with these agents (mainly nausea),” which can be mitigated in the majority of patients with appropriate education and close follow up — but is not done consistently.

Similarly, “the cost differences are also expected, since GLP-1 receptor agonists tend to be more expensive.”

On the other hand, the higher rates of hospitalizations with GLP-1 agonists compared to SGLT2 inhibitors “requires further exploration and confirmation,” Kosiborod said.

But he suspects this may be due to residual confounding, “since GLP-1 agonists are typically initiated later in the type 2 diabetes treatment algorithm,” so these patients could have lengthier, more difficult-to-manage type 2 diabetes with more comorbidities despite the propensity matching.

Poonawalla and Schwab are employed by Humana. Kosiborod has disclosed research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk; and consulting fees from Amarin, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Glytec, Intarcia, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis .

This article first appeared on Medscape.com

Drug adherence, healthcare use, medical costs, and heart failure rates were better among patients with type 2 diabetes who were newly prescribed a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in a real-world, observational study.

Composite cardiovascular (CV) outcomes were similar between the two drug classes.

Insiya Poonawalla, PhD, a researcher at Humana Healthcare Research, Flower Mound, Texas, reported the study results in an oral presentation on June 12 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 80th Scientific Sessions.

The investigators matched more than 10,000 patients with type 2 diabetes — half initiated on an SGLT2 inhibitor and half initiated on a GLP-1 agonist — from the Humana database of insurance claims data.

“These findings suggest potential benefits” of SGLT2 inhibitors, “particularly where risk related to heart failure is an important consideration,” Poonawalla said, but as always, any benefits need to be weighed against any risks.

And “while this study provides a pretty complete and current picture of claims until 2018,” it has limitations inherent to observational data (such as possible errors or omissions in the claims data), she conceded.

Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, invited to comment on the research, said this preliminary study was likely too short and small to definitively demonstrate differences in composite CV outcomes between the two drug classes, but he noted that the overall findings are not unexpected.

And often, the particular CV risk profile of an individual patient will point to one or the other of these drug classes as a best fit, he noted.

Too soon to alter clinical practice

Kosiborod, from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, said he nevertheless feels “it would be a bit premature to use these findings as a guide to change clinical practice.”

“The study is relatively small in scope and likely underpowered to examine CV outcomes,” he said in an email interview.

Larger population-based studies and ideally head-to-head randomized controlled trials of various type 2 diabetes agents could compare these two drug classes more definitively, he asserted.

In the meantime, safety profiles of both medication classes “have been well established — in tens of thousands of patients in clinical trials and millions of patients prescribed these therapies in clinical practice,” he noted.

In general, the drugs in both classes are well-tolerated and safe for most patients with type 2 diabetes when used appropriately.

“Certainly, patients with type 2 diabetes and established CV disease (or at high risk for CV complications) are ideal candidates for either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 receptor agonist,” Kosiborod said.

“Given the data we have from outcome trials, an SGLT2 inhibitor would be a better initial strategy in a patient with type 2 diabetes and heart failure (especially heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and/or diabetic kidney disease,” he continued.

On the other hand, “a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be a better initial strategy in a type 2 diabetes patient with (or at very high risk for) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), especially if there is concomitant obesity contributing to the disease process.”

Limited comparisons of these two newer drug classes

“Real-world evidence comparing these two therapeutic classes based on CV outcomes is limited,” Poonawalla said at the start of her presentation, and relative treatment persistence, utilization, and cost data are even less well studied.

To investigate this, the researchers identified patients aged 19 to 89 years who were newly prescribed one of these two types of antidiabetic agents during January 1, 2015 through June 30, 2017.

Poonawalla and senior study author Phil Schwab, PhD, research lead, Humana Healthcare Research, Louisville, Kentucky, clarified the study design and findings in an email to this new organization.

The team matched 5507 patients initiated on a GLP-1 agonist with 5507 patients newly prescribed an SGLT2 inhibitor.

Patients were a mean age of 65 years and 53% were women.

More than a third (37%) had established ASCVD, including myocardial infarction (MI) (7.9%) and stroke (9.8%), and 11.5% had heart failure.

About two thirds were receiving metformin and about a third were receiving insulin.

In the GLP-1 agonist group, more than half of patients were prescribed liraglutide (57%), followed by dulaglutide (33%), exenatide, and lixisenatide (two patients).

In the SGLT2 inhibitor group, close to 70% received canagliflozin, about a quarter received empagliflozin, and the rest received dapagliflozin.

During up to 3.5 years of follow-up, a similar percentage of patients in each group had either an MI, stroke, or died (the primary composite CV outcome) (hazard ratio [HR], 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89 - 1.07).

However, more patients in the GLP-1 agonist group had heart failure or died (the secondary composite CV outcome), driven by a higher rate of heart failure in this group.

But after adjusting for time to events there was no significant between-group difference in the secondary composite CV outcome (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99 - 1.21).

During the 12-months after the initial prescription, patients who were started on a GLP-1 agonist versus an SGLT2 inhibitor had higher mean monthly medical costs, which included hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient visits ($904 vs $834; P < .001).

They also had higher pharmacy costs, which covered all drugs ($891 vs $783; P < .001).

And they were more likely to discontinue treatment (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.10 - 1.21), be hospitalized (14.4% vs 11.9%; P < .001), or visit the ED (27.4% vs 23.5%; P < .001).

“Not too surprising” and “somewhat reassuring”

Overall, Kosiborod did not find the results surprising.

Given the sample size and follow-up time, event rates were probably quite low and insufficient to draw firm conclusions about the composite CV outcomes, he reiterated.

However, given the comparable effects of these two drug types on major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in similar patient populations with type 2 diabetes, it is not too surprising that there were no significant differences in these outcomes.

It was also “somewhat reassuring” to see that heart failure rates were lower with SGLT2 inhibitors, “as one would expect,” he said, because these agents “have been shown to significantly reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure in multiple outcome trials, whereas GLP-1 receptor agonists’ beneficial CV effects appear to be more limited to MACE reduction.”

The higher rates of discontinuation with GLP-1 receptor agonists “is also not a surprise, since patients experience more gastrointestinal tolerability issues with these agents (mainly nausea),” which can be mitigated in the majority of patients with appropriate education and close follow up — but is not done consistently.

Similarly, “the cost differences are also expected, since GLP-1 receptor agonists tend to be more expensive.”

On the other hand, the higher rates of hospitalizations with GLP-1 agonists compared to SGLT2 inhibitors “requires further exploration and confirmation,” Kosiborod said.

But he suspects this may be due to residual confounding, “since GLP-1 agonists are typically initiated later in the type 2 diabetes treatment algorithm,” so these patients could have lengthier, more difficult-to-manage type 2 diabetes with more comorbidities despite the propensity matching.

Poonawalla and Schwab are employed by Humana. Kosiborod has disclosed research support from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim; honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk; and consulting fees from Amarin, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Glytec, Intarcia, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis .

This article first appeared on Medscape.com

Drug adherence, healthcare use, medical costs, and heart failure rates were better among patients with type 2 diabetes who were newly prescribed a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist in a real-world, observational study.

Composite cardiovascular (CV) outcomes were similar between the two drug classes.

Insiya Poonawalla, PhD, a researcher at Humana Healthcare Research, Flower Mound, Texas, reported the study results in an oral presentation on June 12 at the virtual American Diabetes Association (ADA) 80th Scientific Sessions.

The investigators matched more than 10,000 patients with type 2 diabetes — half initiated on an SGLT2 inhibitor and half initiated on a GLP-1 agonist — from the Humana database of insurance claims data.

“These findings suggest potential benefits” of SGLT2 inhibitors, “particularly where risk related to heart failure is an important consideration,” Poonawalla said, but as always, any benefits need to be weighed against any risks.

And “while this study provides a pretty complete and current picture of claims until 2018,” it has limitations inherent to observational data (such as possible errors or omissions in the claims data), she conceded.

Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, invited to comment on the research, said this preliminary study was likely too short and small to definitively demonstrate differences in composite CV outcomes between the two drug classes, but he noted that the overall findings are not unexpected.

And often, the particular CV risk profile of an individual patient will point to one or the other of these drug classes as a best fit, he noted.

Too soon to alter clinical practice

Kosiborod, from Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Missouri, said he nevertheless feels “it would be a bit premature to use these findings as a guide to change clinical practice.”

“The study is relatively small in scope and likely underpowered to examine CV outcomes,” he said in an email interview.

Larger population-based studies and ideally head-to-head randomized controlled trials of various type 2 diabetes agents could compare these two drug classes more definitively, he asserted.

In the meantime, safety profiles of both medication classes “have been well established — in tens of thousands of patients in clinical trials and millions of patients prescribed these therapies in clinical practice,” he noted.

In general, the drugs in both classes are well-tolerated and safe for most patients with type 2 diabetes when used appropriately.

“Certainly, patients with type 2 diabetes and established CV disease (or at high risk for CV complications) are ideal candidates for either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 receptor agonist,” Kosiborod said.

“Given the data we have from outcome trials, an SGLT2 inhibitor would be a better initial strategy in a patient with type 2 diabetes and heart failure (especially heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and/or diabetic kidney disease,” he continued.

On the other hand, “a GLP-1 receptor agonist may be a better initial strategy in a type 2 diabetes patient with (or at very high risk for) atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), especially if there is concomitant obesity contributing to the disease process.”

Limited comparisons of these two newer drug classes