User login

Is This Man's Eczema Spreading?

Answer

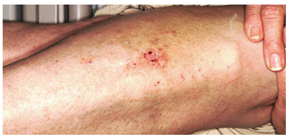

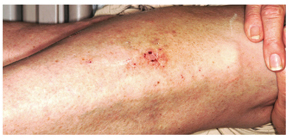

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

Answer

The correct answer is neurodermatitis with associated “id” reaction (choice “c”). The patient probably did have eczema (choice “d”) on his legs, but it became secondarily infected, leading to the later appearance of the arm rash. There was nothing to suggest that this condition was fungal in nature (choice “a”), nor were there any signs of psoriasis (choice “b”).

Discussion Cutaneous reactions to bacterial, fungal, viral, and other antigens have long been recognized as diagnostic entities in dermatology and are usually termed “id” reactions (though an older term, autoeczematization, is also used). “Id” reactions are quite common, particularly in association with inciting conditions such as stasis dermatitis and neurodermatitis. The diagnosis is facilitated by the finding of two different rashes in distant locations that appear sequentially.

This case typifies one of the more common presentations: a bacterid reaction that stems from secondary bacterial infection of neurodermatitis, which is itself secondary to eczema, which, in this particular case, was a manifestation of atopic dermatitis. Recognition of the latter point is significant, since patients with atopic dermatitis are known to have dry, sensitive skin, a lowered threshold for pruritus, and increased numbers of Staphylococcus epidermidis that colonize and invade chronically excoriated skin. This is followed, within days to weeks, by the appearance of a papulovesicular rash at a distant site—often on the volar forearms.

The most common presentation of the bacterid phenomenon starts with stasis dermatitis (venous stasis disease), which becomes, in turn, pruritic and excoriated, then secondarily infected. Inflammatory tinea pedis can trigger a fungal id (“fungid”) reaction at distant sites, especially on the hands and fingers. Acute herpes simplex virus outbreaks are another known culprit, resulting in a more generalized, erythema multiforme–like eruption.

Whatever the trigger, the secondary “id” rash is, by definition, distant to the original, usually symmetrical in distribution, and most often composed of morphologically different lesions. In addition to the arms, it can also involve the neck, trunk, hands, and feet.

Treatment Treatment is twofold, as it must address both the precipitating infection (in this case, with cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days) and the underlying skin condition (in this case, with topical fluocinolone 0.05% ointment applied bid to the legs and daily use of emollients). In severe cases, we often prescribe a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone as well. Direct treatment of the arm rash is not necessary, since it will clear with treatment of the triggering condition.

A 30-year-old man presents with a pruritic rash that first affected both legs and was followed two weeks later by the appearance of a different but equally pruritic rash on his volar forearms. These rashes have persisted despite the use of OTC topical steroid and antifungal creams, triple-antibiotic ointment, and frequent application of rubbing alcohol. Eczema has been a problem throughout the patient’s life, but since his 20s, it has mostly affected his lower legs. As a result, he has gotten into the habit of scratching, even fantasizing about being able to do so at home. Despite being remarkably atopic, with seasonal allergies and generally sensitive skin, he claims to be otherwise healthy. Examination of the patient’s legs shows heavily lichenified papulosquamous involvement of both legs. There are numerous focal areas of scabbing, redness, and edema, which sharply spare the skin under his socks, thin out, then disappear well below the knees. The patient is even observed scratching these areas as the history is taken, and readily admits doing so several times a day. A fairly dense, symmetrical papulovesicular rash is noted on both volar forearms, with only a few lesions remaining intact because of scratching. Elsewhere, his elbows, knees, scalp, and nail plates are free of significant changes.

Infant with Unrelenting Rash

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

Answer

The correct answer is intertrigo (choice “a”), an inflammatory condition seen only where skin touches skin—the so-called intertriginous areas such as axillae, groins, and in the case of babies, the rolls of their necks. Read on for further discussion.

Intertrigo is often mistaken for “yeast infection” (choice “b”). While yeast can colonize and worsen intertrigo, it is not the main cause of the problem.

Intertrigo is often difficult to treat, which leads many patients and providers to apply several different topical medications. It is therefore not unusual to see intertrigo worsened by way of an irritant or contact dermatitis (choice “c”) from one or more of these products. But again, this is not the basic nature of the problem.

Impetigo (choice “d”) is a superficial infection caused by a secondary staph and/or strep infection of skin disrupted by excoriated acne or eczema. Usually a localized process, it typically demonstrates a honey-colored surface on an eroded base, and looks entirely different from our patient’s rash.

Discussion

Warmth, friction, and moisture all conspire to result in maceration (disruption of barrier function); when chronic in nature, this manifests as an inflammatory rash in intertriginous areas. The classic example is seen in the inframammary area in obese women, with a worsening condition in warmer weather. But it can occur in any patient at any age, given the right conditions. The baby who drools into the cute chubby folds of its neck is a good example, for more than one reason.

For parents, the appearance of this rash is alarming to say the least. Everyone offers an opinion, from grandparents to pharmacists. Multiple creams not only fail to help, they often seem to make things worse. Primary care providers are dismayed to find that antiyeast creams don’t work, which often leads them to try a different antiyeast preparation—with the same result.

The explanation is simple: It is intertrigo, not an infection. Candida, being a ubiquitous contaminant of skin, is also an opportunistic organism that can play a role in intertrigo, but the latter is usually more about inflammation than it is infection. Even oral antiyeast medications such as fluconazole are of little help. In the unusual instance when Candida is a major player, multiple discrete erythematous papular erosions are seen as so-called “satellites” on the periphery of the process. Diabetes and/or immunosuppression are often involved in those instances.

Treatment

In this case, successful treatment entailed twice-daily application of a half-and-half mixture of hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and oxiconazole cream. Also recommended was the use of once-daily two-minute compresses of Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate powder, OTC, mixed with water according to package instructions), which dries the area.

Recurrences can be prevented with the application of a combination product containing miconazole cream and talcum-based powder at any sign of a flare; in the case of infants and children, care should be taken to avoid inhalation of the powder. (Miconazole, while ineffective as a treatment for intertrigo, is beneficial for prevention.) Starch-based powders are potentially counterproductive, since Candida actively feeds on starch.

When intertrigo occurs in the more classic inframammary location, a stronger steroid (such as triamcinolone 0.1% cream) is mixed with the oxiconazole. Additional strategies for dealing with perspiration include applying an actual antiperspirant to the area and/or cutting an old cotton t-shirt into strips that are then placed between the breasts and chest wall to cut down on chafing and provide absorption.

A 5-month-old baby is brought for urgent evaluation of a rash that has persisted for more than a month, despite the use of numerous OTC and prescription creams. The latter include clotrimazole and miconazole, neither of which helped much. This morning, the parents started applying starch powder and nystatin cream to the site. It is difficult to tell if the child is suffering from the condition, but the parents and referring pediatrician are certainly worried. The child is otherwise healthy, with appropriate weight increases, and still nursing, taking no solid foods. There is no history of persistent diarrhea and no family history of atopy. On examination, the child’s rash is an impressive red with an erosive center. It covers the entire anterior neck, but is especially accented in the anterior fold of the neck skin. Very little, if any, edema is present, and there is no tenderness elicited on palpation. The site is still covered with excess powder from this morning’s treatment attempt. A survey of the scalp, the diaper area, the mouth, and elsewhere on the face reveals no other areas of rash. The child’s development appears quite normal in all respects.

"Athlete's Foot" That Won't Go Away

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

ANSWER

The one thing least likely to help is changing to white socks (choice “a”), since there is no reason to believe sock color has any effect, one way or the other, on the problem. There are numerous myths in society regarding athlete’s foot; these will be addressed in the discussion section.

When treatment appears to fail, it is usually a good idea to consider other diagnostic possibilities (choice “b”). In this case, these might have included bacterial or yeast infection, among others.

In stubborn or severe cases of tinea pedis, a 10- to 14-day course of terbinafine (choice “c”) is an acceptable treatment option, with only a modest risk of untoward effects. Continued topical application of terbinafine or other prescription-strength antifungal cream will probably be necessary to prevent flares.

Patient and family education (choice “d”) is arguably the single most important step to take in such cases, for reasons that will be delineated in the discussion.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates several aspects of this diagnosis, which is estimated to affect up to 70% of the general population at one time or another in their lives. Our patient’s age, the presentation of the condition—very specifically affecting the webspace between the fourth and fifth toes (between the third and fourth toes far less commonly)—and the presence of chronic itching and maceration are all quite typical of this most common form of tinea pedis.

But just as typical is the persistent nature of the problem: Despite treatment, it often recurs, much to the patient’s distress. The two creams the patient had tried were among the least effective choices (massive advertising campaigns notwithstanding). Eventually, the patient’s immune system will likely fend off this infection; better bathing habits, less occlusive footwear, and less sweating can help. “Catching” this form of tinea pedis is related far more to these favorable conditions and to individual susceptibility than it is to the inevitable exposure to this ubiquitous dermatophyte.

Surprisingly, the first reports of this diagnosis in the United States were not made until the 1920s. The suspicion was that the organism, Trichophyton rubrum, had spread from very limited endemic areas to the rest of the world as a result of the massive movement of soldiers and civilian populations during and after WWI. The general increase in more occlusive forms of footwear was also thought to be a contributing factor.

Many myths sprang up over time regarding this condition. The “white sock” myth was so prevalent that it was probably responsible for two generations’ predominant choice of sock color. The use of white socks was also mistakenly thought to ward off foot odor, which in turn was thought to be caused by fungi.

Regarding the supposed contagious nature of the interdigital form of tinea pedis: Many a married couple has coexisted for decades without the husband “giving” it to the spouse, who is far less likely to represent a favorable host.

Three other forms of tinea pedis eventually evolved, including the hyperkeratotic type (also known as “moccasin variety” tinea pedis), which presents with a scaly, asymptomatic chronic rash around the rim of the feet; the inflammatory type, which presents with the acute appearance of vesicles and pustules on the soles of the feet, is highly pruritic, and almost always has a zoophilic source (cats being the most common); and the far less common ulcerative type, which presents with extensive vesicles, blisters, and erosions, is most often seen on the feet of patients with severe diabetes living in hot, humid conditions, and is usually from zoophilic sources as well.

When reasonable treatment fails, or KOH is negative, or the diagnosis is in doubt for any reason, consideration must be given to other potential explanations. For example, a similar condition can be caused by gram-negative organisms such as Proteus or Pseudomonas. A gram-positive organism called Corynebacterium minitissimum can eventuate in a chronic interdigital rash. Staph and strep can gain entry to the skin through preexisting, tinea pedis–caused breaks in the skin and eventuate in impressive cases of cellulitis, sometimes affecting the entire leg. Contact dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis also belong in the differential.

Our patient was successfully treated with OTC terbinafine cream.

An 18-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of bilateral “athlete’s foot” present for months despite the application of tolnaftate and clotrimazole creams. These both relieved itching, but the problem quickly returned, especially when the weather turned warm. Besides objecting to his foot odor, the patient’s family also worries that his condition is contagious—even though the man’s father already has occasional athlete’s foot. Aside from mild seasonal allergies, the patient is reportedly in excellent health. He has never had any significant skin diseases and is not taking any medications regularly. Inspection of the problem reveals marked maceration bilaterally between the fourth and fifth toes, under which is faint erythema. A KOH prep of the readily obtained material is examined microscopically under the usual 10x magnification, and numerous hyphal (fungal) elements are positively identified, in effect confirming the diagnosis of tinea pedis.

Woman Worried Skin Change May Produce Scars

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

A 45-year-old nurse self-refers for evaluation of changes on her nose and upper forehead. These began about five years ago but in the past few months have become alarming in their progression. The condition is largely asymptomatic and wanes a bit each winter, but overall it has grown considerably over the years—now threatening to produce scarring. The patient denies having any other significant medical issues (ie, joint pain, fever, or malaise). She has never had skin cancer but does acknowledge getting “too much sun” every summer while gardening. She denies any history of foreign travel. As a nurse, she has worked in cardiology exclusively. There is no known family history of skin disease. On exam, the lesions are fairly impressive—especially on the nasal bridge, where there is focal, significant erosion surrounded by peeling skin, all on an erythematous base that is roughly 3 cm in its maximum dimension and polygonal in shape. Despite these changes, surface adnexae (pores, follicles, skin lines) on this lesion are largely intact, except on the superior margin, where definite scarring is seen. Similar changes are seen at the forehead/scalp interface, but with some small areas of scarring alopecia noted focally. Overall, the patient’s skin is fair, but with little overt evidence of sun damage. Her elbows, knees, scalp, and fingernails are free of pathologic changes.

40 Year Old "Wart" Suddenly Changes

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

An 87-year-old man presents for evaluation of a lesion on his left fifth finger that has grown and become ulcerated in the past five months. There is almost no pain in the lesion, which the patient insists was a “wart” for the 40 years prior to these recent changes. Over the years, he has treated his wart with acids, curettement, and liquid nitrogen, to no effect. A recent seven-day course of cephalexin (500 mg tid) also failed to help. Additional history taking reveals that the patient is a farmer who spent his entire life working outdoors every day, year-round. There is no history of immunosuppression. His medications include metoprolol and hydrochlorothiazide. Closer inspection of the lesion reveals a 9-mm, centrally eroded nodule overlying the dorsal proximal interphalangeal joint. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with a surface that looks and feels smooth and is nontender, with minimal redness. There are no palpable nodes in the epitrochlear or axillary locations. Elsewhere, the patient’s skin is remarkably sun-damaged, with numerous actinic keratoses, solar lentigines, and solar atrophy evident, especially on his hands.

Rash Emerges After 18 Holes of Golf

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

When an asymptomatic rash appeared rather suddenly on both of her legs, a 54-year-old woman sought medical evaluation by her primary care provider. He diagnosed contact dermatitis and prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Forty-eight hours later, with no signs of improvement evident, the patient seeks and is granted a same-day appointment with dermatology. The patient denies any previous occurrences of such a rash and further denies having joint pain, fever, or malaise. She had not taken any new medications prior to the rash’s onset; furthermore, she only occasionally uses OTC medicines. A thorough history reveals that two days before the rash appeared, on one of the first hot days of the summer (with a temperature above 95°F), the woman played 18 holes of golf. The rash itself is strikingly red and affects both lower legs symmetrically, from mid-calf to just above the ankles. There, it ends abruptly with a linear, transverse border. There is no tenderness or increased warmth appreciated on palpation, nor is there any nodularity, vesiculation, or other disruption of the skin’s surface. Distinct, complete blanching is noted on firm digital palpation.

An Unexpected Effect of Crohn's

ANSWER

The correct answer is Sweet’s syndrome (choice “a”), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Read on for a discussion of this condition.

Mastocytosis (choice “b”) can present with solitary lesions (“mastocytoma”), but biopsy would have shown a marked increase in mast cells, not the mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes seen in this biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum (choice “c”) lesions eventually ulcerate, and biopsy would have revealed a mixed infiltrate instead of the purely neutrophilic one seen. Cellulitis (choice “d”) would have manifested acutely, quickly becoming suppurative, in contrast to the persistence seen with this lesion.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in 1964 and has since been organized into three basic categories: the classic type, often idiopathic since most cases are of unknown origin; malignancy-associated, typically hematologic (eg, myelogenous leukemia); and drug induced, which was first described in association with sulfa-trimethoprim.

The classic presentation can be triggered by, among other things, upper respiratory infections, pregnancy, and inflammatory bowel disease—as in our patient, whose lesion is quite typical. Arguably the most significant association is with a malignancy, a search for which is undertaken when other possible triggers are absent.

The gold standard for treatment of Sweet’s syndrome is systemic corticosteroids, but other drugs have been used with success, including colchicine and dapsone. This patient is being successfully treated with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion, selected because her disease is very limited. Complete blood count and manual differential diagnosis failed to show any evidence for leukemia.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Sweet’s syndrome (choice “a”), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Read on for a discussion of this condition.

Mastocytosis (choice “b”) can present with solitary lesions (“mastocytoma”), but biopsy would have shown a marked increase in mast cells, not the mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes seen in this biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum (choice “c”) lesions eventually ulcerate, and biopsy would have revealed a mixed infiltrate instead of the purely neutrophilic one seen. Cellulitis (choice “d”) would have manifested acutely, quickly becoming suppurative, in contrast to the persistence seen with this lesion.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in 1964 and has since been organized into three basic categories: the classic type, often idiopathic since most cases are of unknown origin; malignancy-associated, typically hematologic (eg, myelogenous leukemia); and drug induced, which was first described in association with sulfa-trimethoprim.

The classic presentation can be triggered by, among other things, upper respiratory infections, pregnancy, and inflammatory bowel disease—as in our patient, whose lesion is quite typical. Arguably the most significant association is with a malignancy, a search for which is undertaken when other possible triggers are absent.

The gold standard for treatment of Sweet’s syndrome is systemic corticosteroids, but other drugs have been used with success, including colchicine and dapsone. This patient is being successfully treated with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion, selected because her disease is very limited. Complete blood count and manual differential diagnosis failed to show any evidence for leukemia.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Sweet’s syndrome (choice “a”), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Read on for a discussion of this condition.

Mastocytosis (choice “b”) can present with solitary lesions (“mastocytoma”), but biopsy would have shown a marked increase in mast cells, not the mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes seen in this biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum (choice “c”) lesions eventually ulcerate, and biopsy would have revealed a mixed infiltrate instead of the purely neutrophilic one seen. Cellulitis (choice “d”) would have manifested acutely, quickly becoming suppurative, in contrast to the persistence seen with this lesion.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in 1964 and has since been organized into three basic categories: the classic type, often idiopathic since most cases are of unknown origin; malignancy-associated, typically hematologic (eg, myelogenous leukemia); and drug induced, which was first described in association with sulfa-trimethoprim.

The classic presentation can be triggered by, among other things, upper respiratory infections, pregnancy, and inflammatory bowel disease—as in our patient, whose lesion is quite typical. Arguably the most significant association is with a malignancy, a search for which is undertaken when other possible triggers are absent.

The gold standard for treatment of Sweet’s syndrome is systemic corticosteroids, but other drugs have been used with success, including colchicine and dapsone. This patient is being successfully treated with topical clobetasol cream under occlusion, selected because her disease is very limited. Complete blood count and manual differential diagnosis failed to show any evidence for leukemia.

A 47-year-old woman presents with a lesion that first appeared on her arm two months ago. The lesion has grown increasingly tender and large and has persisted despite a course of antibiotics (cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days). She denies any history of similar problems but does relate a 20-year history of Crohn’s disease. She was recently hospitalized for care of her Crohn’s-related pyoderma gangrenosum, which occured on her legs. Despite all this, the patient otherwise feels well, reporting no fever or malaise. Examination reveals a woman who looks her stated age, with a 2.5-cm brownish red round plaque located on the dorsal right forearm. Little if any erythema extends beyond the sharply defined border. The surface of the plaque looks slightly blistery, but on palpation the lesion feels solid and not fluid filled. It is moderately tender to touch and much warmer than the surrounding skin. No lymph nodes can be palpated in either epitrochlear or axillary areas, and no similar lesions are seen elsewhere. A 5-mm punch biopsy is performed on the lesion. The results show a dense neutrophilic infiltrate, accentuated on the dermal papillae.

Lesion Has Doubled in Size in Two Weeks

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since the history and appearance of the lesion are quite consistent with keratoacanthoma—considered by most to be a low-grade form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). All the other statements are true.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are quite common, especially in older patients with fair, sun-damaged skin. They appear on areas of the skin that have been directly exposed to the sun. The dorsal forearm is especially typical, but KAs can also appear on the face, hands, shoulders, and back.

The relatively rapid growth is in marked contrast to most other skin cancers and has been linked to the human papillomavirus DNA, which has been found in these lesions. However, by no means is this connection universally accepted as the cause, even though immune suppression, in the susceptible patient, does appear to play a role.

Microscopically, KAs bear a marked resemblance to SCCs. Indeed, they have been known to metastasize in rare instances, although most will involute (albeit with minor scarring) on their own, without treatment. The standard of treatment in this country is to remove KAs surgically and to submit the tissue for pathologic examination, which would officially show “SCC, KA type,” or “well-differentiated SCC.”

The differential diagnosis includes wart, invasive SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. KAs have nothing to do with bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since the history and appearance of the lesion are quite consistent with keratoacanthoma—considered by most to be a low-grade form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). All the other statements are true.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are quite common, especially in older patients with fair, sun-damaged skin. They appear on areas of the skin that have been directly exposed to the sun. The dorsal forearm is especially typical, but KAs can also appear on the face, hands, shoulders, and back.

The relatively rapid growth is in marked contrast to most other skin cancers and has been linked to the human papillomavirus DNA, which has been found in these lesions. However, by no means is this connection universally accepted as the cause, even though immune suppression, in the susceptible patient, does appear to play a role.

Microscopically, KAs bear a marked resemblance to SCCs. Indeed, they have been known to metastasize in rare instances, although most will involute (albeit with minor scarring) on their own, without treatment. The standard of treatment in this country is to remove KAs surgically and to submit the tissue for pathologic examination, which would officially show “SCC, KA type,” or “well-differentiated SCC.”

The differential diagnosis includes wart, invasive SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. KAs have nothing to do with bacterial infection.

ANSWER

The one incorrect statement is choice “a,” since the history and appearance of the lesion are quite consistent with keratoacanthoma—considered by most to be a low-grade form of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). All the other statements are true.

DISCUSSION/TREATMENT

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are quite common, especially in older patients with fair, sun-damaged skin. They appear on areas of the skin that have been directly exposed to the sun. The dorsal forearm is especially typical, but KAs can also appear on the face, hands, shoulders, and back.

The relatively rapid growth is in marked contrast to most other skin cancers and has been linked to the human papillomavirus DNA, which has been found in these lesions. However, by no means is this connection universally accepted as the cause, even though immune suppression, in the susceptible patient, does appear to play a role.

Microscopically, KAs bear a marked resemblance to SCCs. Indeed, they have been known to metastasize in rare instances, although most will involute (albeit with minor scarring) on their own, without treatment. The standard of treatment in this country is to remove KAs surgically and to submit the tissue for pathologic examination, which would officially show “SCC, KA type,” or “well-differentiated SCC.”

The differential diagnosis includes wart, invasive SCC, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. KAs have nothing to do with bacterial infection.

Six weeks ago, a new lesion began to appear on the forearm of this 63-year-old woman; it has grown rapidly in the ensuing time. She first went to her primary care provider, who diagnosed a staph infection and prescribed an antibiotic that hasn’t helped. The lesion, while asymptomatic, is nonetheless alarming; it has doubled in size in the past two weeks, which is why the patient now presents to the dermatology clinic. Her medical history includes well-controlled hypertension and a remote incidence of several basal cell carcinomas. On examination, the patient’s skin, in general, is severely sun-damaged, as evidenced by a weathered, leathery look to all exposed skin, as well as by multiple telangiectasias and solar lentigines. The lesion in question is a striking 1.8-cm dome-like nodule with a central keratotic core, located on the mid-dorsal forearm. Smooth and shiny, the surface of this firm nodule is also covered with tiny telangiectasias. Careful examination of the rest of the patient’s skin shows no other worrisome lesions.

Eyelids Are Irritated (But Eyes Are Fine)

ANSWER

The one incorrect answer is yeast infection (choice “c”). All the others should be included in the list of possible explanations. Given the inherent dryness and relatively low temperature of the affected area, as well as the nonresponse to imidazole cream, candida is quite unlikely.

DISCUSSION

The only way this patient could acquire a yeast infection in this area is if she were immunosuppressed. Eyelid dermatitis is seen daily in derm practices; patients are often referred by frustrated primary care providers who are unable to help.

This problem is almost never seen in male patients, which suggests the involvement of makeup, eye shadow, or skin care products, especially cleansers. But even when these are changed or eliminated, the problem often continues.

Here’s why: Women—especially those with sensitive skin in general—will often manifest that sensitivity in areas where skin is the thinnest and most accessible, and therefore the most easily damaged. Once the problem starts, it is difficult for these women to leave it alone. They scratch it, rub it, and often apply multiple products to it, all of which only serves to worsen it.

In contrast, most men use no products at all on their faces, let alone “eye creams” or special cleansers. The male version of this problem is the equally ubiquitous chronic anterior scrotal rash—which develops for many of the same reasons.

Many of these women also happen to have a history of atopic dermatitis, which not only means extraordinarily sensitive skin all over the body but also tends to involve unusually dry skin (xerosis). These women have multiple allergies to contactants, such as nickel and nail polish.

TREATMENT

As the cycle of applying different (unhelpful) products to the problem area continues, women are increasingly likely to use products with irritating ingredients. If they are to get any relief, this cycle must be broken.

I usually prescribe hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment (not the cream, which has a drying effect) or tacrolimus 0.1% ointment (either treatment to be used twice a day), plus once-a-day application of the greasiest moisturizer they can stand (eg, petroleum jelly) over the affected area.

They can use this same approach with future episodes, although there must be strict limits on the duration (two weeks) and frequency of the application. Overuse of the steroid can lead to glaucoma and permanent thinning of already thin skin.

Obviously, it would be of great utility if the patient were in fact found to be allergic to nail polish, but in my experience, most women have eliminated that as a potential cause before they get to a dermatology provider. The same goes for makeup.

The eyelid dermatitis patient certainly could be suffering from seborrhea or psoriasis; however, in such cases, the same itch-scratch-itch cycle often results, and the treatment would be identical.

ANSWER

The one incorrect answer is yeast infection (choice “c”). All the others should be included in the list of possible explanations. Given the inherent dryness and relatively low temperature of the affected area, as well as the nonresponse to imidazole cream, candida is quite unlikely.

DISCUSSION

The only way this patient could acquire a yeast infection in this area is if she were immunosuppressed. Eyelid dermatitis is seen daily in derm practices; patients are often referred by frustrated primary care providers who are unable to help.

This problem is almost never seen in male patients, which suggests the involvement of makeup, eye shadow, or skin care products, especially cleansers. But even when these are changed or eliminated, the problem often continues.

Here’s why: Women—especially those with sensitive skin in general—will often manifest that sensitivity in areas where skin is the thinnest and most accessible, and therefore the most easily damaged. Once the problem starts, it is difficult for these women to leave it alone. They scratch it, rub it, and often apply multiple products to it, all of which only serves to worsen it.

In contrast, most men use no products at all on their faces, let alone “eye creams” or special cleansers. The male version of this problem is the equally ubiquitous chronic anterior scrotal rash—which develops for many of the same reasons.