User login

The Value of Certainty in Diagnosis

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

ANSWER

For a number of reasons (discussed more fully below), the correct answer is to follow up with the pathologist (choice “c”); the biopsying provider, who is the only person to have seen the lesion, is responsible for resolving any discordance between the report and the clinical presentation/appearance.

Simply accepting the report as fact and notifying the patient of the result (choice “a”) is unacceptable. Removing more tissue from the base of the site (choice “b”) is not likely to provide any useful clinical information. Watching the site for change (choice “d”) ignores the possibility that the original lesion has already spread.

DISCUSSION

Skin tags, also known as fibroepithelioma or acrochorda, are extremely common, benign lesions encountered daily by almost all medical providers. Melanoma in tag form is decidedly unusual, but far from unknown. Around 80% of melanomas are essentially flat (macular), and about 10% are nodular. The rest, from a morphologic standpoint, are all over the map. They can be red, blue, and even white. Contrary to popular misconception, they rarely itch, and you probably wouldn’t want to depend on your dog to alert you to their presence.

My point? Although we conceive of melanomas as looking a certain way (a useful and necessary view), the reality is that their morphologic presentations are astonishingly diverse. They include pedunculated tags.

This means that unless we have a very good reason to do otherwise, we should send almost every skin lesion we remove for pathologic examination. Simple, small tags, warts, and the like can be safely discarded. But anything of substance, or anything that appears to be the least bit odd, must be submitted to pathology.

Furthermore, the pathology reports must be carefully read and the results connected to the particular lesion. This case illustrates that necessity nicely. With its black tip, this lesion was more than a little worrisome. When no mention was made of the pigmentary changes, a call to the pathologist was in order.

In this case, the pathologist was more than happy to order new and deeper cuts to be made in the specimen. Within two days, he issued a new report, which showed benign nevoid changes that explained the dark pigment and failed to show any atypia. Then, and only then, were we able to give the results to the patient.

This principle can be extrapolated to results from other types of tests. They are not to be accepted blindly by the ordering provider, who is in the unique position of having seen the patient.

A 48-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of several relatively minor skin problems. One of them is a taglike lesion on the skin of her low back. Present for years, it has begun to bother her a bit; it rubs against her clothes and is occasionally traumatized enough to bleed. The patient isn’t worried about it but does want it removed. Her history is unremarkable, with no personal or family history of skin cancer. She is fair and tolerates the sun poorly, but for that reason she has limited her sun exposure throughout her life. The lesion is a 5 x 6–mm taglike nodule located in the midline of her low back. At first glance, it appears to be traumatized. But on closer inspection, the distal half of the lesion is simply black, with indistinct margins. On palpation, the lesion is firmer than most tags but nontender. A few drops of lidocaine with epinephrine are injected into the base of the lesion, which is then saucerized. Minor bleeding is easily controlled by electrocautery, and the lesion is submitted to pathology. The resultant report shows a simple benign tag. No explanation for the darker portion of the lesion is given.

Subungual Lesion Hasn’t Grown Out: Benign or Malignant?

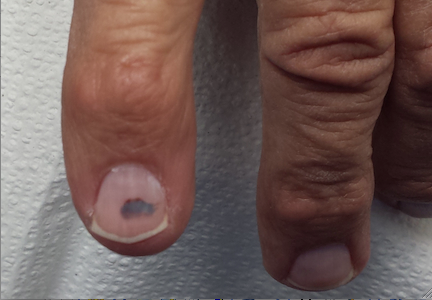

Eight months ago, this 67-year-old man first noticed a dark lesion under his second fingernail. Since then, it has not changed. It is completely asymptomatic, but it hasn’t grown out, either, which concerns the patient and his primary care provider. The latter recommends a visit to dermatology.

The patient denies any history of trauma to either the finger or the nail and says he hasn’t had any similar problems with his other fingernails. His history does include excessive sun exposure, particularly during his young adulthood. He has had several basal cell carcinomas removed over the years, mostly from his face.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is 4 mm, dark brown to black, and macular. It is located under the mid portion of his right index fingernail. No abnormality of the nail plate itself is felt, and all his other fingernails appear normal.

A presumptive diagnosis of subungual hematoma is challenged by the given history of at least eight months without any change or movement to the lesion. This fact is at odds with the nature of a hematoma.

Continue for the procedure and discussion >>

PROCEDURE

Since the lesion cannot simply be ignored, given the real (albeit remote) possibility of melanoma, how to proceed is thoroughly discussed with the patient. As a result, the finger is anesthetized by digital block technique, using 2% plain lidocaine. A tourniquet is then created from a small exam glove with the tip of the index finger removed. This portion of the glove is then rolled up to the base of the finger, and when the patient holds his hand above his heart, it provides a relatively bloodless field.

Then, under clean conditions, the portion of the nail plate covering the lesion is removed with iris scissors, revealing the expected subungual hematoma (characterized by clotted blood adhering to the underside of the nail plate). The nail bed now appears totally normal. After the tourniquet is released, the site is cleaned and dressed and the patient reassured as to the benignancy of the lesion.

DISCUSSION

Subungual melanoma is unusual but greatly feared because of its generally poor prognosis. This is not due to any inherent virulence but rather to delayed diagnosis. Such a delay may be caused by disbelief or denial on the part of the patient. A notable case is that of musician Bob Marley, who died in 1981 from metastatic melanoma that had started under a toenail. (Legend continues to maintain that the trauma of kicking a soccer ball caused the cancer, though this is totally anecdotal.)

Marley, who was born in Jamaica and was of mixed African and European ancestry, embodies the fact that while persons with darker skin develop melanoma far less frequently than do fair-skinned individuals, they tend to get it in locations with the least amount of pigment (eg, palms, soles, mouth, under nails). Most patients, and many unwary providers, have simply never been exposed to this very real phenomenon.

Melanoma that develops in these peripheral locations is called acral lentiginous melanoma. Hands, feet, thumbs, and halluces are the most common locations. Nearly all these melanomas begin as tan to brown macules and tend to enlarge and darken over time. They eventually transition to a vertical growth phase that allows penetration of superficial vasculature by tumor cells, leading to metastasis.

The presentation of this patient’s lesion is inconsistent with that of subungual melanoma, which usually involves the periungual margins (especially the cuticle, which eventually darkens focally, a phenomenon termed Hutchinson’s sign). In any case, whenever a subungual melanoma is suspected, a biopsy must be performed.

In all likelihood, this patient sustained trauma to this nail but forgot about it. In another two months or so, his subungual hematoma would have grown out, proving its benignancy. But in the circumstances, we had no choice but to take his given history seriously and properly evaluate the lesion.

Continue for Joe Monroe's learning points >>

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Acral lentiginous melanoma is associated with a generally poor prognosis, primarily due to delayed diagnosis.

• This type of melanoma is typically found on the scalp, palms, or soles, under nails, and even in the mouth. The thumb and big toe are the most common locations when hands or feet are involved.

• Patients with darker skin are far less likely to develop melanoma than their fair-skinned counterparts—but when they do, the aforementioned locations are the most common.

• For nondermatology providers, affected patients should probably be referred to dermatology for evaluation and possible biopsy.

• For any subungual or periungual lesion noted on physical examination, a history should be sought.

Eight months ago, this 67-year-old man first noticed a dark lesion under his second fingernail. Since then, it has not changed. It is completely asymptomatic, but it hasn’t grown out, either, which concerns the patient and his primary care provider. The latter recommends a visit to dermatology.

The patient denies any history of trauma to either the finger or the nail and says he hasn’t had any similar problems with his other fingernails. His history does include excessive sun exposure, particularly during his young adulthood. He has had several basal cell carcinomas removed over the years, mostly from his face.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is 4 mm, dark brown to black, and macular. It is located under the mid portion of his right index fingernail. No abnormality of the nail plate itself is felt, and all his other fingernails appear normal.

A presumptive diagnosis of subungual hematoma is challenged by the given history of at least eight months without any change or movement to the lesion. This fact is at odds with the nature of a hematoma.

Continue for the procedure and discussion >>

PROCEDURE

Since the lesion cannot simply be ignored, given the real (albeit remote) possibility of melanoma, how to proceed is thoroughly discussed with the patient. As a result, the finger is anesthetized by digital block technique, using 2% plain lidocaine. A tourniquet is then created from a small exam glove with the tip of the index finger removed. This portion of the glove is then rolled up to the base of the finger, and when the patient holds his hand above his heart, it provides a relatively bloodless field.

Then, under clean conditions, the portion of the nail plate covering the lesion is removed with iris scissors, revealing the expected subungual hematoma (characterized by clotted blood adhering to the underside of the nail plate). The nail bed now appears totally normal. After the tourniquet is released, the site is cleaned and dressed and the patient reassured as to the benignancy of the lesion.

DISCUSSION

Subungual melanoma is unusual but greatly feared because of its generally poor prognosis. This is not due to any inherent virulence but rather to delayed diagnosis. Such a delay may be caused by disbelief or denial on the part of the patient. A notable case is that of musician Bob Marley, who died in 1981 from metastatic melanoma that had started under a toenail. (Legend continues to maintain that the trauma of kicking a soccer ball caused the cancer, though this is totally anecdotal.)

Marley, who was born in Jamaica and was of mixed African and European ancestry, embodies the fact that while persons with darker skin develop melanoma far less frequently than do fair-skinned individuals, they tend to get it in locations with the least amount of pigment (eg, palms, soles, mouth, under nails). Most patients, and many unwary providers, have simply never been exposed to this very real phenomenon.

Melanoma that develops in these peripheral locations is called acral lentiginous melanoma. Hands, feet, thumbs, and halluces are the most common locations. Nearly all these melanomas begin as tan to brown macules and tend to enlarge and darken over time. They eventually transition to a vertical growth phase that allows penetration of superficial vasculature by tumor cells, leading to metastasis.

The presentation of this patient’s lesion is inconsistent with that of subungual melanoma, which usually involves the periungual margins (especially the cuticle, which eventually darkens focally, a phenomenon termed Hutchinson’s sign). In any case, whenever a subungual melanoma is suspected, a biopsy must be performed.

In all likelihood, this patient sustained trauma to this nail but forgot about it. In another two months or so, his subungual hematoma would have grown out, proving its benignancy. But in the circumstances, we had no choice but to take his given history seriously and properly evaluate the lesion.

Continue for Joe Monroe's learning points >>

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Acral lentiginous melanoma is associated with a generally poor prognosis, primarily due to delayed diagnosis.

• This type of melanoma is typically found on the scalp, palms, or soles, under nails, and even in the mouth. The thumb and big toe are the most common locations when hands or feet are involved.

• Patients with darker skin are far less likely to develop melanoma than their fair-skinned counterparts—but when they do, the aforementioned locations are the most common.

• For nondermatology providers, affected patients should probably be referred to dermatology for evaluation and possible biopsy.

• For any subungual or periungual lesion noted on physical examination, a history should be sought.

Eight months ago, this 67-year-old man first noticed a dark lesion under his second fingernail. Since then, it has not changed. It is completely asymptomatic, but it hasn’t grown out, either, which concerns the patient and his primary care provider. The latter recommends a visit to dermatology.

The patient denies any history of trauma to either the finger or the nail and says he hasn’t had any similar problems with his other fingernails. His history does include excessive sun exposure, particularly during his young adulthood. He has had several basal cell carcinomas removed over the years, mostly from his face.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is 4 mm, dark brown to black, and macular. It is located under the mid portion of his right index fingernail. No abnormality of the nail plate itself is felt, and all his other fingernails appear normal.

A presumptive diagnosis of subungual hematoma is challenged by the given history of at least eight months without any change or movement to the lesion. This fact is at odds with the nature of a hematoma.

Continue for the procedure and discussion >>

PROCEDURE

Since the lesion cannot simply be ignored, given the real (albeit remote) possibility of melanoma, how to proceed is thoroughly discussed with the patient. As a result, the finger is anesthetized by digital block technique, using 2% plain lidocaine. A tourniquet is then created from a small exam glove with the tip of the index finger removed. This portion of the glove is then rolled up to the base of the finger, and when the patient holds his hand above his heart, it provides a relatively bloodless field.

Then, under clean conditions, the portion of the nail plate covering the lesion is removed with iris scissors, revealing the expected subungual hematoma (characterized by clotted blood adhering to the underside of the nail plate). The nail bed now appears totally normal. After the tourniquet is released, the site is cleaned and dressed and the patient reassured as to the benignancy of the lesion.

DISCUSSION

Subungual melanoma is unusual but greatly feared because of its generally poor prognosis. This is not due to any inherent virulence but rather to delayed diagnosis. Such a delay may be caused by disbelief or denial on the part of the patient. A notable case is that of musician Bob Marley, who died in 1981 from metastatic melanoma that had started under a toenail. (Legend continues to maintain that the trauma of kicking a soccer ball caused the cancer, though this is totally anecdotal.)

Marley, who was born in Jamaica and was of mixed African and European ancestry, embodies the fact that while persons with darker skin develop melanoma far less frequently than do fair-skinned individuals, they tend to get it in locations with the least amount of pigment (eg, palms, soles, mouth, under nails). Most patients, and many unwary providers, have simply never been exposed to this very real phenomenon.

Melanoma that develops in these peripheral locations is called acral lentiginous melanoma. Hands, feet, thumbs, and halluces are the most common locations. Nearly all these melanomas begin as tan to brown macules and tend to enlarge and darken over time. They eventually transition to a vertical growth phase that allows penetration of superficial vasculature by tumor cells, leading to metastasis.

The presentation of this patient’s lesion is inconsistent with that of subungual melanoma, which usually involves the periungual margins (especially the cuticle, which eventually darkens focally, a phenomenon termed Hutchinson’s sign). In any case, whenever a subungual melanoma is suspected, a biopsy must be performed.

In all likelihood, this patient sustained trauma to this nail but forgot about it. In another two months or so, his subungual hematoma would have grown out, proving its benignancy. But in the circumstances, we had no choice but to take his given history seriously and properly evaluate the lesion.

Continue for Joe Monroe's learning points >>

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Acral lentiginous melanoma is associated with a generally poor prognosis, primarily due to delayed diagnosis.

• This type of melanoma is typically found on the scalp, palms, or soles, under nails, and even in the mouth. The thumb and big toe are the most common locations when hands or feet are involved.

• Patients with darker skin are far less likely to develop melanoma than their fair-skinned counterparts—but when they do, the aforementioned locations are the most common.

• For nondermatology providers, affected patients should probably be referred to dermatology for evaluation and possible biopsy.

• For any subungual or periungual lesion noted on physical examination, a history should be sought.

Unsightly But Not Painful

At the end of his dermatology visit for an entirely different problem, this 48-year-old man mentions that his toenails have become discolored and misshapen in recent years. Consulting a long line of providers about the problem has not produced a successful solution. Among the treatments tried were oral formulations of fluconazole, ketoconazole, and terbinafine, as well as various OTC topical products, including window-cleaning fluid, tea tree oil, and petroleum jelly.

Ten years ago, he was persuaded to have his right big toenail surgically removed, in hopes of a cure. However, when the nail grew back, it gradually reverted to its previous appearance.

He claims to be in good health otherwise and takes no prescription medications (aside from the attempts to treat his toenail problem). For many years, he has worked in construction, wearing heavy 9 in boots. For the past seven years, he has worked 12-hour days.

He denies any pain in his toes and admits that his main motivation for seeking help with this problem is that his wife is convinced she will “catch” it and end up with toenails like his.

EXAMINATION

Eight out of 10 toenails, including the first and second toes of both feet, are decidedly yellowed and thickened, displaying multiple focal areas of breakage on the ends of the nail plates. No such changes are noted on his fingernails. The surrounding skin on his feet and hands is entirely within normal limits, except for a rim of faint scaling around the periphery of both feet. The latter is KOH positive for fungal elements.

Continue for Joe Monroe's Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Onychomycosis, also known as tinea unguium, is an extremely common problem, affecting approximately 10% of adults in the US (but only 4% to 6% in Canada). Common as it is, onychomycosis is also vastly overdiagnosed and frequently mistreated, as illustrated by this particular case. This combination creates confusion among patients and clinicians alike.

Several different organisms can cause what we call onychomycosis, but the most common is Trichophyton rubrum, a dermatophytic fungus also responsible for most cases of “athlete’s foot” and “jock itch.” The changes seen in onychomycotic toenails include yellow to brown discoloration, thickening, and often, brittle ends of the nail plates. Unfortunately, other diseases—including but not limited to psoriasis and lichen planus—can cause similar changes.

In this case, the classical appearance of the patient’s toenails, along with the athlete’s foot and involvement of the big toenails, made this a relatively easy diagnosis. In other circumstances, confirmation could have been provided from a simple nail clipping. Sent for pathologic examination, it would have exhibited signs of fungal organisms.

Even with a firm diagnosis, successful treatment is problematic. This man’s employment and choice of footwear—along with a family history that was revealed through further questioning—all conspire against him. Ideal treatment would eventuate in a cure, but with these factors against him, it is unlikely.

For example, a four-month course of the best treatment (terbinafine 250 mg/d), would probably clear his nails. However, the chance of recurrence would be at least 50%, for two reasons. One: His environment and heredity would leave him no less susceptible than before. Two: Continual or repeat exposure to this ubiquitous organism is almost certain.

If his toenails cleared, he could simply continue his use of oral terbinafine (taking 250 mg once or twice a week) in hopes of maintaining that state. This would constitute an off-label use of that drug, since there have been no studies of its effectiveness or safety with ongoing use. This “prevention” strategy has been tried with some success, however.

The good news? First of all, the patient’s wife of 20 years has shown no signs of developing onychomycosis and is unlikely ever to do so. It appears that women are not as susceptible as men, either by virtue of less perspiration, circumstance of career, or choice of footwear. And furthermore, onychomycosis is not an infection in any sense that we typically use that word. It almost never causes pain or even redness, except in association with nail dystrophy so severe that the nail plate cuts into adjacent live tissue.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Onychomycosis is extremely common, affecting about 10% of adults in this country.

• Heredity and environmental factors play significant roles in a person’s susceptibility to onychomycosis.

• Men are far more likely to experience onychomycosis than women.

• Surgical removal of onychomycotic toenails is completely ineffective.

• Petroleum jelly, window-cleaning fluid, and tea tree oil have not proven effective in treating onychomycosis.

• First and second toenails are usually the first to be affected by this condition, presumably as a result of trauma.

At the end of his dermatology visit for an entirely different problem, this 48-year-old man mentions that his toenails have become discolored and misshapen in recent years. Consulting a long line of providers about the problem has not produced a successful solution. Among the treatments tried were oral formulations of fluconazole, ketoconazole, and terbinafine, as well as various OTC topical products, including window-cleaning fluid, tea tree oil, and petroleum jelly.

Ten years ago, he was persuaded to have his right big toenail surgically removed, in hopes of a cure. However, when the nail grew back, it gradually reverted to its previous appearance.

He claims to be in good health otherwise and takes no prescription medications (aside from the attempts to treat his toenail problem). For many years, he has worked in construction, wearing heavy 9 in boots. For the past seven years, he has worked 12-hour days.

He denies any pain in his toes and admits that his main motivation for seeking help with this problem is that his wife is convinced she will “catch” it and end up with toenails like his.

EXAMINATION

Eight out of 10 toenails, including the first and second toes of both feet, are decidedly yellowed and thickened, displaying multiple focal areas of breakage on the ends of the nail plates. No such changes are noted on his fingernails. The surrounding skin on his feet and hands is entirely within normal limits, except for a rim of faint scaling around the periphery of both feet. The latter is KOH positive for fungal elements.

Continue for Joe Monroe's Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Onychomycosis, also known as tinea unguium, is an extremely common problem, affecting approximately 10% of adults in the US (but only 4% to 6% in Canada). Common as it is, onychomycosis is also vastly overdiagnosed and frequently mistreated, as illustrated by this particular case. This combination creates confusion among patients and clinicians alike.

Several different organisms can cause what we call onychomycosis, but the most common is Trichophyton rubrum, a dermatophytic fungus also responsible for most cases of “athlete’s foot” and “jock itch.” The changes seen in onychomycotic toenails include yellow to brown discoloration, thickening, and often, brittle ends of the nail plates. Unfortunately, other diseases—including but not limited to psoriasis and lichen planus—can cause similar changes.

In this case, the classical appearance of the patient’s toenails, along with the athlete’s foot and involvement of the big toenails, made this a relatively easy diagnosis. In other circumstances, confirmation could have been provided from a simple nail clipping. Sent for pathologic examination, it would have exhibited signs of fungal organisms.

Even with a firm diagnosis, successful treatment is problematic. This man’s employment and choice of footwear—along with a family history that was revealed through further questioning—all conspire against him. Ideal treatment would eventuate in a cure, but with these factors against him, it is unlikely.

For example, a four-month course of the best treatment (terbinafine 250 mg/d), would probably clear his nails. However, the chance of recurrence would be at least 50%, for two reasons. One: His environment and heredity would leave him no less susceptible than before. Two: Continual or repeat exposure to this ubiquitous organism is almost certain.

If his toenails cleared, he could simply continue his use of oral terbinafine (taking 250 mg once or twice a week) in hopes of maintaining that state. This would constitute an off-label use of that drug, since there have been no studies of its effectiveness or safety with ongoing use. This “prevention” strategy has been tried with some success, however.

The good news? First of all, the patient’s wife of 20 years has shown no signs of developing onychomycosis and is unlikely ever to do so. It appears that women are not as susceptible as men, either by virtue of less perspiration, circumstance of career, or choice of footwear. And furthermore, onychomycosis is not an infection in any sense that we typically use that word. It almost never causes pain or even redness, except in association with nail dystrophy so severe that the nail plate cuts into adjacent live tissue.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Onychomycosis is extremely common, affecting about 10% of adults in this country.

• Heredity and environmental factors play significant roles in a person’s susceptibility to onychomycosis.

• Men are far more likely to experience onychomycosis than women.

• Surgical removal of onychomycotic toenails is completely ineffective.

• Petroleum jelly, window-cleaning fluid, and tea tree oil have not proven effective in treating onychomycosis.

• First and second toenails are usually the first to be affected by this condition, presumably as a result of trauma.

At the end of his dermatology visit for an entirely different problem, this 48-year-old man mentions that his toenails have become discolored and misshapen in recent years. Consulting a long line of providers about the problem has not produced a successful solution. Among the treatments tried were oral formulations of fluconazole, ketoconazole, and terbinafine, as well as various OTC topical products, including window-cleaning fluid, tea tree oil, and petroleum jelly.

Ten years ago, he was persuaded to have his right big toenail surgically removed, in hopes of a cure. However, when the nail grew back, it gradually reverted to its previous appearance.

He claims to be in good health otherwise and takes no prescription medications (aside from the attempts to treat his toenail problem). For many years, he has worked in construction, wearing heavy 9 in boots. For the past seven years, he has worked 12-hour days.

He denies any pain in his toes and admits that his main motivation for seeking help with this problem is that his wife is convinced she will “catch” it and end up with toenails like his.

EXAMINATION

Eight out of 10 toenails, including the first and second toes of both feet, are decidedly yellowed and thickened, displaying multiple focal areas of breakage on the ends of the nail plates. No such changes are noted on his fingernails. The surrounding skin on his feet and hands is entirely within normal limits, except for a rim of faint scaling around the periphery of both feet. The latter is KOH positive for fungal elements.

Continue for Joe Monroe's Discussion...

DISCUSSION

Onychomycosis, also known as tinea unguium, is an extremely common problem, affecting approximately 10% of adults in the US (but only 4% to 6% in Canada). Common as it is, onychomycosis is also vastly overdiagnosed and frequently mistreated, as illustrated by this particular case. This combination creates confusion among patients and clinicians alike.

Several different organisms can cause what we call onychomycosis, but the most common is Trichophyton rubrum, a dermatophytic fungus also responsible for most cases of “athlete’s foot” and “jock itch.” The changes seen in onychomycotic toenails include yellow to brown discoloration, thickening, and often, brittle ends of the nail plates. Unfortunately, other diseases—including but not limited to psoriasis and lichen planus—can cause similar changes.

In this case, the classical appearance of the patient’s toenails, along with the athlete’s foot and involvement of the big toenails, made this a relatively easy diagnosis. In other circumstances, confirmation could have been provided from a simple nail clipping. Sent for pathologic examination, it would have exhibited signs of fungal organisms.

Even with a firm diagnosis, successful treatment is problematic. This man’s employment and choice of footwear—along with a family history that was revealed through further questioning—all conspire against him. Ideal treatment would eventuate in a cure, but with these factors against him, it is unlikely.

For example, a four-month course of the best treatment (terbinafine 250 mg/d), would probably clear his nails. However, the chance of recurrence would be at least 50%, for two reasons. One: His environment and heredity would leave him no less susceptible than before. Two: Continual or repeat exposure to this ubiquitous organism is almost certain.

If his toenails cleared, he could simply continue his use of oral terbinafine (taking 250 mg once or twice a week) in hopes of maintaining that state. This would constitute an off-label use of that drug, since there have been no studies of its effectiveness or safety with ongoing use. This “prevention” strategy has been tried with some success, however.

The good news? First of all, the patient’s wife of 20 years has shown no signs of developing onychomycosis and is unlikely ever to do so. It appears that women are not as susceptible as men, either by virtue of less perspiration, circumstance of career, or choice of footwear. And furthermore, onychomycosis is not an infection in any sense that we typically use that word. It almost never causes pain or even redness, except in association with nail dystrophy so severe that the nail plate cuts into adjacent live tissue.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Onychomycosis is extremely common, affecting about 10% of adults in this country.

• Heredity and environmental factors play significant roles in a person’s susceptibility to onychomycosis.

• Men are far more likely to experience onychomycosis than women.

• Surgical removal of onychomycotic toenails is completely ineffective.

• Petroleum jelly, window-cleaning fluid, and tea tree oil have not proven effective in treating onychomycosis.

• First and second toenails are usually the first to be affected by this condition, presumably as a result of trauma.

Relatively Asymptomatic, but Still Problematic

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

ANSWER

The correct answer is seborrheic dermatitis (choice “d”), a common cause of penile rashes that typically manifests initially as chronic dandruff or in some other form on the head or neck.

Herpes simplex (choice “a”) is certainly common, but it likely would have presented with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base. Furthermore, each episode would have been limited to about two weeks, and the eruption would have produced noticeable symptoms and responded to the valacyclovir.

Yeast infection (choice “b”), while often diagnosed, is in reality unusual, especially in the circumcised and otherwise healthy male. Nystatin, although far from the ideal treatment, should have had some effect.

Fixed drug eruption (FDE; choice “c”) could have been a suspect, had there been a drug to blame. FDE usually presents as a brownish red, shiny round macule that appears and reappears in the same area with repeated exposure to the same drug. The penile shaft is a favorite area for it. Drugs known to trigger FDE include NSAIDs, sulfa, tetracycline, penicillin, pseudoephedrine, and aspirin.

DISCUSSION

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD), also known as seborrhea, is an extremely common chronic papulosquamous disorder patterned on the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. Although not directly caused by the highly lipophilic commensal yeast Malassezia furfur, it does appear to be related to increases in the number of those organisms, as well as to immunologic abnormalities and increased production of sebum. It can range from a mild scaly rash to whole-body erythroderma and can affect an astonishing range of areas, including the genitals.

SD almost always manifests with dandruff (or “cradle cap” in the infant), followed by faint scaling in and around the ears or on the face (eg, nasolabial folds, brows, and glabella), mid chest, axillae, periumbilical region, and genitals. Below the head and neck, SD often mystifies the nondermatology provider, who tends to call it “fungal infection” or, when it’s seen in moist intertriginous skin, “yeast infection.”

SD, especially in this case, represents the perfect example of the need to “look elsewhere” for clues when confronted with a mysterious rash. Patients can certainly have more than one dermatologic diagnosis at a time, but a single explanation is considerably more likely and should therefore be sought. In this case, corroboration for the diagnosis of SD was readily found by looking for it in its known locations.

SD can take on different looks, including a distinctly annular morphology, especially in patients with darker skin. It can occasionally be severe in patients with Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, or a history of stroke. This case mirrors my experience in that I see increased stress as a major precipitating factor in the worsening of pre-existing SD.

In addition to the items already mentioned, the differential for penile rashes includes lichen planus. However, the lesions of lichen planus tend to have a distinctly purple appearance and well-defined margins, and on the penis, they tend to spill over onto the penile corona and glans.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

In this case, treatment comprised a combination of oxiconazole lotion and 2.5% hydrocortisone cream. Many other combinations have been used successfully, including pimecrolimus or tacrolimus combined with ketoconazole cream.

Whatever is used, a cure will not be forthcoming, since the condition is almost always chronic. The main value of an accurate diagnosis in such a case lies in easing the patient’s mind regarding the terrible diseases he doesn’t have.

A 31-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a penile rash that has repeatedly manifested and resolved over a period of months. Relatively asymptomatic, the eruption has persisted despite a two-week course of valacyclovir 500 mg bid, followed by a month-long course of topical nystatin cream tid. The patient says he has been in otherwise good health. However, he reports being under a great deal of stress, as his job and his marriage ended within the space of a few weeks. He denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage. Other than those already mentioned, the patient has taken no medications, prescription or OTC. The problem area is obvious: a bright pink papulosquamous patch on the distal right shaft of his circumcised penis. This round lesion, which measures more than 3 cm in diameter, has a shiny appearance and slightly irregular margins. No other areas of involvement are noted in the genital area. However, there is a similar scaly pink rash behind both of the patient’s ears, as well as patches of dandruff in the scalp, especially over and behind the ears. A similar rash is seen in the patient’s umbilicus and surrounding area.

Unexpected Source for Itch

A 70-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a scalp rash that has been present for months. Complaining bitterly of the itching in his scalp, he gives a history that includes treatment attempts with a number of medications, including prescription ketoconazole shampoo, oral antibiotics (eg, minocycline), and a course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for three weeks)—none of which has had a positive impact on the problem.

His wife, who is with him, at first denies and then finally admits to having an itchy scalp as well. Neither has a history of prior skin problems.

The patient’s history is significant for type 2 diabetes and for well-controlled hypertension. He has been retired for many years and lives at home with his wife.

EXAMINATION

The patient appears disheveled, confused, and dirty. He is grossly oriented as to time and place, but hard of hearing and difficult to communicate with as a result.

His hair is greasy and dirty, as well as matted down in places. On closer inspection, scabs are noted in his scalp; they are widely distributed but especially heavy in the occipital and supra-auricular scalp. Many flakes of dandruff (some quite large) can also be seen.

Raising the thick hair over his nuchal scalp reveals a whitish sheen. Under 10x magnification, multiple tiny white papules are observed attached to each hair shaft, which accounts for the sheen. When examined under the microscope, the papules are clearly identified as nits. No adult lice are noted.

Significant tender adenopathy is elicited on palpation of the posterior neck area.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

Clearly, the basic problem is head lice (pediculosis capitis), with everything else stemming from it. This can be quite confusing for many reasons, not least of which is that one thinks of head lice as a pediatric problem.

The related issue is bacterial infection secondary to scratching and picking, usually from coagulase-negative staph. Minocycline or trimethoprim/sulfa would have been adequate for treatment but of course would not address the main problem: the lice.

Ironically, one of the other impediments to a correct diagnosis was the severity of this patient’s case. It was, without a doubt, the worst I’ve seen in a 30-year career. The nits were so numerous as to render them almost impossible to see without magnification.

There’s little doubt that his wife had them too, adding to the potential for others (eg, grandchildren) around them to be infested as well. Furthermore, this represented a source for re-infestation despite treatment efforts.

Luckily, neither the organisms nor the nits remain viable for long off the body, which means they cannot reside and replicate on inanimate objects. Nonhumans cannot give or get human head lice. Given the organism’s need for warmth and aversion to light, there’s little chance for involvement in areas other than the scalp.

Both the patient and his wife were treated with oral and topical ivermectin. The topical form is applied once to a damp scalp, left on for 10 minutes, then rinsed out. It not only kills the adult organisms but also appears to render the nits nonviable—potentially obviating the necessity of using a nit comb.

The oral ivermectin (150 µg/kg ) was prescribed as follows: four 3-mg tablets now and another four tablets in 10 days to kill any remaining adults. Oral ivermectin is usually not necessary in the treatment of head lice and was only used in this case because of the severity.

Since their cases were so severe, I also advised them both to consider shaving their heads first to facilitate effective treatment. Again, this step is seldom necessary except in the most extreme cases. However, it also facilitated management of their secondary pyoderma, which was treated with trimethoprim/sulfa (double strength, bid for a week).

Since the itching caused by head lice is essentially an allergic reaction to the organism’s protein, that symptom may persist for some time, albeit with gradually diminishing intensity.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take-home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pediculosis capitis (head lice) is seen mostly in children but affects adults as well.

• Pyoderma, secondary to scratching, can mislead the diagnostician and thereby delay diagnosis of the underlying problem.

• Oral trimethoprim/sulfa is often used to treat lice-associated pyoderma but does nothing directly to kill the lice themselves.

• The itching from head lice is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the lice protein and can take months after infestation to develop.

• Conversely, itching will develop early on in patients who have been sensitized by having had head lice in the past.

• The use of topical ivermectin has proven to be exceptionally effective in clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE: The author discloses having spoken and written about topical ivermectin at the behest of the manufacturer, but this article was not part of that process, nor is it supported by the product’s manufacturer in any way.

A 70-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a scalp rash that has been present for months. Complaining bitterly of the itching in his scalp, he gives a history that includes treatment attempts with a number of medications, including prescription ketoconazole shampoo, oral antibiotics (eg, minocycline), and a course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for three weeks)—none of which has had a positive impact on the problem.

His wife, who is with him, at first denies and then finally admits to having an itchy scalp as well. Neither has a history of prior skin problems.

The patient’s history is significant for type 2 diabetes and for well-controlled hypertension. He has been retired for many years and lives at home with his wife.

EXAMINATION

The patient appears disheveled, confused, and dirty. He is grossly oriented as to time and place, but hard of hearing and difficult to communicate with as a result.

His hair is greasy and dirty, as well as matted down in places. On closer inspection, scabs are noted in his scalp; they are widely distributed but especially heavy in the occipital and supra-auricular scalp. Many flakes of dandruff (some quite large) can also be seen.

Raising the thick hair over his nuchal scalp reveals a whitish sheen. Under 10x magnification, multiple tiny white papules are observed attached to each hair shaft, which accounts for the sheen. When examined under the microscope, the papules are clearly identified as nits. No adult lice are noted.

Significant tender adenopathy is elicited on palpation of the posterior neck area.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

Clearly, the basic problem is head lice (pediculosis capitis), with everything else stemming from it. This can be quite confusing for many reasons, not least of which is that one thinks of head lice as a pediatric problem.

The related issue is bacterial infection secondary to scratching and picking, usually from coagulase-negative staph. Minocycline or trimethoprim/sulfa would have been adequate for treatment but of course would not address the main problem: the lice.

Ironically, one of the other impediments to a correct diagnosis was the severity of this patient’s case. It was, without a doubt, the worst I’ve seen in a 30-year career. The nits were so numerous as to render them almost impossible to see without magnification.

There’s little doubt that his wife had them too, adding to the potential for others (eg, grandchildren) around them to be infested as well. Furthermore, this represented a source for re-infestation despite treatment efforts.

Luckily, neither the organisms nor the nits remain viable for long off the body, which means they cannot reside and replicate on inanimate objects. Nonhumans cannot give or get human head lice. Given the organism’s need for warmth and aversion to light, there’s little chance for involvement in areas other than the scalp.

Both the patient and his wife were treated with oral and topical ivermectin. The topical form is applied once to a damp scalp, left on for 10 minutes, then rinsed out. It not only kills the adult organisms but also appears to render the nits nonviable—potentially obviating the necessity of using a nit comb.

The oral ivermectin (150 µg/kg ) was prescribed as follows: four 3-mg tablets now and another four tablets in 10 days to kill any remaining adults. Oral ivermectin is usually not necessary in the treatment of head lice and was only used in this case because of the severity.

Since their cases were so severe, I also advised them both to consider shaving their heads first to facilitate effective treatment. Again, this step is seldom necessary except in the most extreme cases. However, it also facilitated management of their secondary pyoderma, which was treated with trimethoprim/sulfa (double strength, bid for a week).

Since the itching caused by head lice is essentially an allergic reaction to the organism’s protein, that symptom may persist for some time, albeit with gradually diminishing intensity.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take-home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pediculosis capitis (head lice) is seen mostly in children but affects adults as well.

• Pyoderma, secondary to scratching, can mislead the diagnostician and thereby delay diagnosis of the underlying problem.

• Oral trimethoprim/sulfa is often used to treat lice-associated pyoderma but does nothing directly to kill the lice themselves.

• The itching from head lice is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the lice protein and can take months after infestation to develop.

• Conversely, itching will develop early on in patients who have been sensitized by having had head lice in the past.

• The use of topical ivermectin has proven to be exceptionally effective in clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE: The author discloses having spoken and written about topical ivermectin at the behest of the manufacturer, but this article was not part of that process, nor is it supported by the product’s manufacturer in any way.

A 70-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a scalp rash that has been present for months. Complaining bitterly of the itching in his scalp, he gives a history that includes treatment attempts with a number of medications, including prescription ketoconazole shampoo, oral antibiotics (eg, minocycline), and a course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for three weeks)—none of which has had a positive impact on the problem.

His wife, who is with him, at first denies and then finally admits to having an itchy scalp as well. Neither has a history of prior skin problems.

The patient’s history is significant for type 2 diabetes and for well-controlled hypertension. He has been retired for many years and lives at home with his wife.

EXAMINATION

The patient appears disheveled, confused, and dirty. He is grossly oriented as to time and place, but hard of hearing and difficult to communicate with as a result.

His hair is greasy and dirty, as well as matted down in places. On closer inspection, scabs are noted in his scalp; they are widely distributed but especially heavy in the occipital and supra-auricular scalp. Many flakes of dandruff (some quite large) can also be seen.

Raising the thick hair over his nuchal scalp reveals a whitish sheen. Under 10x magnification, multiple tiny white papules are observed attached to each hair shaft, which accounts for the sheen. When examined under the microscope, the papules are clearly identified as nits. No adult lice are noted.

Significant tender adenopathy is elicited on palpation of the posterior neck area.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

Clearly, the basic problem is head lice (pediculosis capitis), with everything else stemming from it. This can be quite confusing for many reasons, not least of which is that one thinks of head lice as a pediatric problem.

The related issue is bacterial infection secondary to scratching and picking, usually from coagulase-negative staph. Minocycline or trimethoprim/sulfa would have been adequate for treatment but of course would not address the main problem: the lice.

Ironically, one of the other impediments to a correct diagnosis was the severity of this patient’s case. It was, without a doubt, the worst I’ve seen in a 30-year career. The nits were so numerous as to render them almost impossible to see without magnification.

There’s little doubt that his wife had them too, adding to the potential for others (eg, grandchildren) around them to be infested as well. Furthermore, this represented a source for re-infestation despite treatment efforts.

Luckily, neither the organisms nor the nits remain viable for long off the body, which means they cannot reside and replicate on inanimate objects. Nonhumans cannot give or get human head lice. Given the organism’s need for warmth and aversion to light, there’s little chance for involvement in areas other than the scalp.

Both the patient and his wife were treated with oral and topical ivermectin. The topical form is applied once to a damp scalp, left on for 10 minutes, then rinsed out. It not only kills the adult organisms but also appears to render the nits nonviable—potentially obviating the necessity of using a nit comb.

The oral ivermectin (150 µg/kg ) was prescribed as follows: four 3-mg tablets now and another four tablets in 10 days to kill any remaining adults. Oral ivermectin is usually not necessary in the treatment of head lice and was only used in this case because of the severity.

Since their cases were so severe, I also advised them both to consider shaving their heads first to facilitate effective treatment. Again, this step is seldom necessary except in the most extreme cases. However, it also facilitated management of their secondary pyoderma, which was treated with trimethoprim/sulfa (double strength, bid for a week).

Since the itching caused by head lice is essentially an allergic reaction to the organism’s protein, that symptom may persist for some time, albeit with gradually diminishing intensity.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take-home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pediculosis capitis (head lice) is seen mostly in children but affects adults as well.

• Pyoderma, secondary to scratching, can mislead the diagnostician and thereby delay diagnosis of the underlying problem.

• Oral trimethoprim/sulfa is often used to treat lice-associated pyoderma but does nothing directly to kill the lice themselves.

• The itching from head lice is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the lice protein and can take months after infestation to develop.

• Conversely, itching will develop early on in patients who have been sensitized by having had head lice in the past.

• The use of topical ivermectin has proven to be exceptionally effective in clinical trials.

DISCLOSURE: The author discloses having spoken and written about topical ivermectin at the behest of the manufacturer, but this article was not part of that process, nor is it supported by the product’s manufacturer in any way.

It Doesn't Hurt, So It Must Not Be Serious

A 60-year-old man presents to a free clinic for evaluation of a “knot” in his left lower axilla. He first noticed it several months ago. Even though the lesion grew, the patient reasoned that it couldn’t be too serious since “it didn’t hurt.” But in the past month, the lesion has become much more firm and darkened.

The patient denies any other health problems. He has an 80-pack-year history of smoking. He has never had health insurance and as a result has carefully avoided any interaction with the health care establishment.

Additional history-taking reveals that he has become markedly short of breath in the past few months, which he attributes to his smoking. He denies any abdominal pain or headache. As a young man, he spent 20 years working as a roofer, often going shirtless in hot weather.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress. He is accompanied by his wife, who participates in the history-taking process. Both call attention to the lesion in question, a 5.5-cm dark subcutaneous mass in the left lower axilla. The overlying skin is dark as well, and on palpation, the mass is found to be fixed and firm. Palpation elsewhere in the axillae, as well as in the head and neck, fails to detect any other lesions.

The rest of the patient's type III skin (easily tanned, seldom burned) shows limited evidence of sun damage. A few minor solar lentigines are seen on the trunk, but none stand out. Then the patient's wife points out a barely discernible, depigmented, poorly defined macule on the left lateral back. It measures about 2 cm. This lesion, she reports, "used to be real black. Then it turned scabby, and then it lost all its color. It's been this way ever since."

Continue reading for the diagnostic studies...

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

An incisional biopsy of the residual lesion on his back is performed. Two-thirds of the macule is removed, the wound is closed with sutures, and the specimen is submitted for pathologic examination. The resulting report indicates a superficial spreading melanoma, Breslow depth (vertical thickness) of 1.6 mm, with evidence of significant regression and a brisk mitotic rate─all predictors of metastatic potential.

Accordingly, the patient is referred to the appropriate surgical specialist, who confirms the micrometastatic nature of the axillary node and refers the patient to oncology for imaging studies that will determine the extent of metastasis. The residual primary tumor is excised with 2-cm margins.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon—known as regression—in which part or all of a cutaneous melanoma is rendered invisible over time by the reaction of the immune system (although not before it has a chance to spread). Not uncommonly, these patients are diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and no primary lesion is ever discovered.

A variation on this theme is the so-called amelanotic melanoma, which can present initially in a wide variety of forms—papules, nodules, or macules; in shades of pink, blue, white, or "flesh." But unlike our patient, these cases do not involve regression.

This patient and his wife assumed that because the primary lesion had essentially disappeared, it must have been safe. And of course, they failed to connect it with the new axillary nodule.

At this writing, the extent of the patient’s disease remains to be defined by imaging studies (PET and CT scans). But given the facts of the case, his prognosis at best is guarded. A more hopeful view is that he is living in a time of meaningful discovery of better treatments for advanced melanomas.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Although the classic melanoma is black and essentially flat, it can present in many other forms, including an amelanotic version, the color of which can be pink, blue, white or even skin-colored.

• Infrequently, melanoma presents initially in metastatic form, having spread from an unknown or obscure primary lesion.

• Immune response to a cutaneous melanoma can result in partial or even total destruction of the lesion, a process termed regression.

• Predictors of a relatively poor prognosis for melanoma include: the aforementioned regression, vertical thickness (Breslow depth), mitotic rate, vascular invasion, and the presence of ulceration.

• New masses in known nodal locations require examination of surrounding skin to detect or rule out suspicious lesions.

A 60-year-old man presents to a free clinic for evaluation of a “knot” in his left lower axilla. He first noticed it several months ago. Even though the lesion grew, the patient reasoned that it couldn’t be too serious since “it didn’t hurt.” But in the past month, the lesion has become much more firm and darkened.

The patient denies any other health problems. He has an 80-pack-year history of smoking. He has never had health insurance and as a result has carefully avoided any interaction with the health care establishment.

Additional history-taking reveals that he has become markedly short of breath in the past few months, which he attributes to his smoking. He denies any abdominal pain or headache. As a young man, he spent 20 years working as a roofer, often going shirtless in hot weather.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress. He is accompanied by his wife, who participates in the history-taking process. Both call attention to the lesion in question, a 5.5-cm dark subcutaneous mass in the left lower axilla. The overlying skin is dark as well, and on palpation, the mass is found to be fixed and firm. Palpation elsewhere in the axillae, as well as in the head and neck, fails to detect any other lesions.

The rest of the patient's type III skin (easily tanned, seldom burned) shows limited evidence of sun damage. A few minor solar lentigines are seen on the trunk, but none stand out. Then the patient's wife points out a barely discernible, depigmented, poorly defined macule on the left lateral back. It measures about 2 cm. This lesion, she reports, "used to be real black. Then it turned scabby, and then it lost all its color. It's been this way ever since."

Continue reading for the diagnostic studies...

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

An incisional biopsy of the residual lesion on his back is performed. Two-thirds of the macule is removed, the wound is closed with sutures, and the specimen is submitted for pathologic examination. The resulting report indicates a superficial spreading melanoma, Breslow depth (vertical thickness) of 1.6 mm, with evidence of significant regression and a brisk mitotic rate─all predictors of metastatic potential.

Accordingly, the patient is referred to the appropriate surgical specialist, who confirms the micrometastatic nature of the axillary node and refers the patient to oncology for imaging studies that will determine the extent of metastasis. The residual primary tumor is excised with 2-cm margins.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon—known as regression—in which part or all of a cutaneous melanoma is rendered invisible over time by the reaction of the immune system (although not before it has a chance to spread). Not uncommonly, these patients are diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and no primary lesion is ever discovered.

A variation on this theme is the so-called amelanotic melanoma, which can present initially in a wide variety of forms—papules, nodules, or macules; in shades of pink, blue, white, or "flesh." But unlike our patient, these cases do not involve regression.

This patient and his wife assumed that because the primary lesion had essentially disappeared, it must have been safe. And of course, they failed to connect it with the new axillary nodule.

At this writing, the extent of the patient’s disease remains to be defined by imaging studies (PET and CT scans). But given the facts of the case, his prognosis at best is guarded. A more hopeful view is that he is living in a time of meaningful discovery of better treatments for advanced melanomas.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Although the classic melanoma is black and essentially flat, it can present in many other forms, including an amelanotic version, the color of which can be pink, blue, white or even skin-colored.

• Infrequently, melanoma presents initially in metastatic form, having spread from an unknown or obscure primary lesion.

• Immune response to a cutaneous melanoma can result in partial or even total destruction of the lesion, a process termed regression.

• Predictors of a relatively poor prognosis for melanoma include: the aforementioned regression, vertical thickness (Breslow depth), mitotic rate, vascular invasion, and the presence of ulceration.

• New masses in known nodal locations require examination of surrounding skin to detect or rule out suspicious lesions.

A 60-year-old man presents to a free clinic for evaluation of a “knot” in his left lower axilla. He first noticed it several months ago. Even though the lesion grew, the patient reasoned that it couldn’t be too serious since “it didn’t hurt.” But in the past month, the lesion has become much more firm and darkened.

The patient denies any other health problems. He has an 80-pack-year history of smoking. He has never had health insurance and as a result has carefully avoided any interaction with the health care establishment.

Additional history-taking reveals that he has become markedly short of breath in the past few months, which he attributes to his smoking. He denies any abdominal pain or headache. As a young man, he spent 20 years working as a roofer, often going shirtless in hot weather.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no distress. He is accompanied by his wife, who participates in the history-taking process. Both call attention to the lesion in question, a 5.5-cm dark subcutaneous mass in the left lower axilla. The overlying skin is dark as well, and on palpation, the mass is found to be fixed and firm. Palpation elsewhere in the axillae, as well as in the head and neck, fails to detect any other lesions.

The rest of the patient's type III skin (easily tanned, seldom burned) shows limited evidence of sun damage. A few minor solar lentigines are seen on the trunk, but none stand out. Then the patient's wife points out a barely discernible, depigmented, poorly defined macule on the left lateral back. It measures about 2 cm. This lesion, she reports, "used to be real black. Then it turned scabby, and then it lost all its color. It's been this way ever since."

Continue reading for the diagnostic studies...

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

An incisional biopsy of the residual lesion on his back is performed. Two-thirds of the macule is removed, the wound is closed with sutures, and the specimen is submitted for pathologic examination. The resulting report indicates a superficial spreading melanoma, Breslow depth (vertical thickness) of 1.6 mm, with evidence of significant regression and a brisk mitotic rate─all predictors of metastatic potential.

Accordingly, the patient is referred to the appropriate surgical specialist, who confirms the micrometastatic nature of the axillary node and refers the patient to oncology for imaging studies that will determine the extent of metastasis. The residual primary tumor is excised with 2-cm margins.

Continue reading for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon—known as regression—in which part or all of a cutaneous melanoma is rendered invisible over time by the reaction of the immune system (although not before it has a chance to spread). Not uncommonly, these patients are diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and no primary lesion is ever discovered.

A variation on this theme is the so-called amelanotic melanoma, which can present initially in a wide variety of forms—papules, nodules, or macules; in shades of pink, blue, white, or "flesh." But unlike our patient, these cases do not involve regression.

This patient and his wife assumed that because the primary lesion had essentially disappeared, it must have been safe. And of course, they failed to connect it with the new axillary nodule.

At this writing, the extent of the patient’s disease remains to be defined by imaging studies (PET and CT scans). But given the facts of the case, his prognosis at best is guarded. A more hopeful view is that he is living in a time of meaningful discovery of better treatments for advanced melanomas.

Continue reading for Joe Monroe's take home learning points...

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Although the classic melanoma is black and essentially flat, it can present in many other forms, including an amelanotic version, the color of which can be pink, blue, white or even skin-colored.

• Infrequently, melanoma presents initially in metastatic form, having spread from an unknown or obscure primary lesion.