User login

Retired Tour Guide Intends to Maintain Her Tan

ANSWER

The correct answer is poikiloderma of Civatte (choice “c”), details of which are discussed below.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (choice “a”) can be an early indication of T-cell lymphoma but would probably not be chronic or confined to sun-exposed skin.

Several forms of lupus (choice “b”) can present with poikilodermatous skin changes, but these would probably not be chronic.

Dermatoheliosis (choice “d”) is the term for the collective effects of overexposure to the sun, of which poikiloderma of Civatte is but one example.

DISCUSSION

The French dermatologist Achille Civatte (1877-1956) first described this particular pattern of sun damage in 1923—about the same time that sunbathing became fashionable among the well-off in the post-WWI era. He noted the distinct combination of telangiectasias, hyperpigmentation, and epidermal atrophy affecting the bilateral neck and lower face, combined with sharply defined sparing of the portion of the anterior neck shaded by the chin. Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is extremely common, especially in middle-aged women and, as one might expect, in those with a history of excessive sun exposure over a period of many years.

Though sun-caused, PC is a purely cosmetic issue and does not lead to skin cancer. While it typically causes no symptoms, it does become more obvious with time. The changes are so gradual that others typically notice them before the patient becomes aware.

Transposing these types of skin changes to other locations would make them considerably more worrisome, specifically in the context of possible incipient T-cell lymphoma—one of the very few types of skin cancer that can take years to evolve into frank cancer. But the atrophy, telangiectasias, and discoloration signaling early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are usually seen in non–sun-exposed skin, particularly in the waistline and groin.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is only one of several manifestations termed premycotic. This refers to mycosis fungoides, one of the two most common forms of T-cell lymphoma. Serial biopsy, sometimes over the span of several years, is often used to track such changes.

Pulsed light devices and certain types of lasers have been used successfully to treat PC. Our patient, however, declined treatment, declaring her firm intention to maintain “a healthy tan” year-round.

ANSWER

The correct answer is poikiloderma of Civatte (choice “c”), details of which are discussed below.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (choice “a”) can be an early indication of T-cell lymphoma but would probably not be chronic or confined to sun-exposed skin.

Several forms of lupus (choice “b”) can present with poikilodermatous skin changes, but these would probably not be chronic.

Dermatoheliosis (choice “d”) is the term for the collective effects of overexposure to the sun, of which poikiloderma of Civatte is but one example.

DISCUSSION

The French dermatologist Achille Civatte (1877-1956) first described this particular pattern of sun damage in 1923—about the same time that sunbathing became fashionable among the well-off in the post-WWI era. He noted the distinct combination of telangiectasias, hyperpigmentation, and epidermal atrophy affecting the bilateral neck and lower face, combined with sharply defined sparing of the portion of the anterior neck shaded by the chin. Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is extremely common, especially in middle-aged women and, as one might expect, in those with a history of excessive sun exposure over a period of many years.

Though sun-caused, PC is a purely cosmetic issue and does not lead to skin cancer. While it typically causes no symptoms, it does become more obvious with time. The changes are so gradual that others typically notice them before the patient becomes aware.

Transposing these types of skin changes to other locations would make them considerably more worrisome, specifically in the context of possible incipient T-cell lymphoma—one of the very few types of skin cancer that can take years to evolve into frank cancer. But the atrophy, telangiectasias, and discoloration signaling early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are usually seen in non–sun-exposed skin, particularly in the waistline and groin.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is only one of several manifestations termed premycotic. This refers to mycosis fungoides, one of the two most common forms of T-cell lymphoma. Serial biopsy, sometimes over the span of several years, is often used to track such changes.

Pulsed light devices and certain types of lasers have been used successfully to treat PC. Our patient, however, declined treatment, declaring her firm intention to maintain “a healthy tan” year-round.

ANSWER

The correct answer is poikiloderma of Civatte (choice “c”), details of which are discussed below.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (choice “a”) can be an early indication of T-cell lymphoma but would probably not be chronic or confined to sun-exposed skin.

Several forms of lupus (choice “b”) can present with poikilodermatous skin changes, but these would probably not be chronic.

Dermatoheliosis (choice “d”) is the term for the collective effects of overexposure to the sun, of which poikiloderma of Civatte is but one example.

DISCUSSION

The French dermatologist Achille Civatte (1877-1956) first described this particular pattern of sun damage in 1923—about the same time that sunbathing became fashionable among the well-off in the post-WWI era. He noted the distinct combination of telangiectasias, hyperpigmentation, and epidermal atrophy affecting the bilateral neck and lower face, combined with sharply defined sparing of the portion of the anterior neck shaded by the chin. Poikiloderma of Civatte (PC) is extremely common, especially in middle-aged women and, as one might expect, in those with a history of excessive sun exposure over a period of many years.

Though sun-caused, PC is a purely cosmetic issue and does not lead to skin cancer. While it typically causes no symptoms, it does become more obvious with time. The changes are so gradual that others typically notice them before the patient becomes aware.

Transposing these types of skin changes to other locations would make them considerably more worrisome, specifically in the context of possible incipient T-cell lymphoma—one of the very few types of skin cancer that can take years to evolve into frank cancer. But the atrophy, telangiectasias, and discoloration signaling early cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are usually seen in non–sun-exposed skin, particularly in the waistline and groin.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is only one of several manifestations termed premycotic. This refers to mycosis fungoides, one of the two most common forms of T-cell lymphoma. Serial biopsy, sometimes over the span of several years, is often used to track such changes.

Pulsed light devices and certain types of lasers have been used successfully to treat PC. Our patient, however, declined treatment, declaring her firm intention to maintain “a healthy tan” year-round.

A 60-year-old woman is seen for complaints of skin changes on her neck that have slowly become more noticeable over a period of years. Although asymptomatic, these changes have been observed by others, who brought them to the patient’s attention. The patient worked as a tour guide in Arizona for 20 years, leading groups along desert trails to view native flora and fauna. During that time, she maintained a dark tan almost year-round, tanning easily and never using sunscreen. The patient has type III skin, bluish gray eyes, and light brown hair. Dark brown–to–red mottled pigmentary changes are seen on the sides of her neck; the central portion of the anterior neck is sharply spared. On closer inspection, many fine telangiectasias are noted in these same areas, as well as on the sun-exposed areas of the face. Aside from her skin changes, the patient claims to be quite healthy, with no joint pain, fever, or malaise.

Hair Loss in a 12-Year-Old

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

Is It Ringworm, Herpes— Or Something Else Entirely?

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

A 16-year-old girl is referred to dermatology by her pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on her face. She is currently taking acyclovir (dose unknown) as prescribed by her pediatrician for presumed herpetic infection. Previous treatment attempts with OTC tolnaftate cream and various OTC moisturizers have failed. The rash manifested several weeks ago with two scaly bumps on her left cheek and temple area, which the patient admits to “picking” at. Initially, the lesions itched a bit, but they became larger and more symptomatic after she applied hydrogen peroxide to them several times. She then began to scrub the lesions vigorously with antibacterial soap while continuing to apply the peroxide. Subsequently, she presented to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with “ringworm” (and advised to use tolnaftate cream), and then to her pediatrician, with the aforementioned result. Aside from seasonal allergies and periodic episodes of eczema, the patient’s health is excellent. She has no pets. Examination reveals large, annular, honey-colored crusts focally located on the left side of the patient’s face. Faint pinkness is noted peripherally around the lesions. Modest but palpable adenopathy is detected in the pretragal and submental nodal areas. Though symptomatic, the patient is in no distress. A KOH prep taken from the scaly periphery is negative for fungal elements.

Slowly Spreading Hand Lesions

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

Several months ago, lesions appeared on both of this 48-year-old woman’s hands. They have been completely unresponsive to any of the treatments prescribed by her primary care provider, including oral (terbinafine) and topical antifungal medications.

The lesions, which are asymptomatic, manifested slowly. They first appeared on the dorsa of her hands and then gradually spread until they covered the central portion of both hands. The lesions wax and wane in terms of thickness and extent but never disappear.

The patient denies similar lesions elsewhere. She also denies contact with animals or children. She has never been immunosuppressed and is quite healthy aside from her skin problems. She has a family history but no personal history of diabetes.

EXAMINATION

The condition affects both hands equally. It is composed of intradermal reddish brown papules and plaques that cover the metacarpal areas and extend onto the proximal interphalangeal skin and the distal dorsa. No epidermal component (scale or other broken skin surface) is seen.

The margins of the lesions are arciform, slightly raised, and smooth. The centers of several are concave.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the classic presentation of granuloma annulare (GA), in terms of morphology, distribution, and patient gender. Though this common condition can manifest in a number of locations and in men, it tends to favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities of women. The dorsum of the foot, anterior tibial skin, and elbows are typical locations that make it a relatively easy condition to recognize.

GA can be more difficult to identify, however, when it is generalized or deeper in the dermis. The latter, termed subcutaneous GA, is most common in children, who present with large dark annular patches of discoloration too deep in the dermis to produce any palpable surface changes. The more rare generalized GA can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Biopsy of suspected generalized or subcutaneous GA is necessary to differentiate it from its lookalikes, such as secondary syphilis, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, and tinea.

The annular borders of GA lesions are notorious for deceiving the unwary practitioner into diagnosing fungal infection. But the latter is, by definition, an infection of the outermost layers of the skin on which fungal organisms feed. That process almost invariably produces significant scaling, especially on the periphery of the lesions. Such scaling is completely absent on GA lesions, which also have a papularity and induration rarely seen with superficial fungal infections. In this particular case, the patient denied any potential source for a fungal infection (animals, children) and denied the itching we would expect with one.

The cause of GA is unknown, but it appears to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen. One previous hypothesis held that it was connected to diabetes, but this was proved false.

Ordinary GA resolves on its own (though this can take months)—which is fortunate, since there is no uniformly successful treatment. Many things have been tried, including topical or intralesional steroids and cryotherapy, with varying levels of success. Generalized GA is even more difficult to treat, can linger for years, and can be highly pruritic. Treatments have included hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, potassium iodide, isotretinoin, and PUVA. More recently, biologics are being used with some success.

The bigger problem with GA is simply to consider it in the differential for odd, annular, or generalized lesions.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Granuloma annulare (GA) is often mistaken for fungal infection, but it is an intradermal rather than epidermal process.

• The extensor surfaces of the extremities of women are favored sites for GA lesions.

• Biopsy of suspected GA lesions confirms the diagnosis while ruling out other items in the differential (eg, sarcoidosis and lichen planus).

• GA has no connection to diabetes.

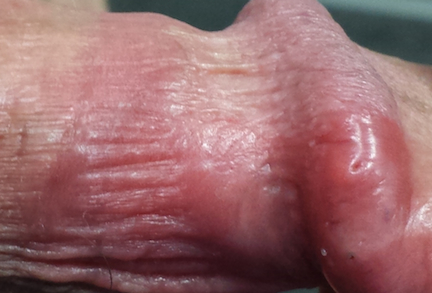

Penile Rash Worries Man (And Wife)

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

A 61-year-old man presents with an asymptomatic but worrisome (to him) penile rash that manifested over a two-day period several weeks ago. OTC miconazole cream, triple-antibiotic creams, and most recently, a two-day course of fluconazole (200 mg bid) have not helped.

The patient denies any sexual exposure outside his marriage, as does his wife. Both are in good health in other respects, although the wife has been treated for lymphoma (long since declared cured).

At first, the patient denies any other skin problems. However, with specific questioning, he admits to having a chronic scaly and slightly itchy rash that periodically appears in the same places: bilateral brows, nasolabial folds, various spots in his beard, and both external ear canals.

Additional history taking reveals that the patient has been under a great deal of stress lately. His father recently died, leaving him to deal with a number of issues, and his work shift changed, requiring him to sleep during the day and work at night.

EXAMINATION

The penile rash is macular, smooth, strikingly red, and shiny. It covers the dorsal, distal penile shaft, spilling onto the glans. It looks wet but is quite dry. His groin, upper intergluteal area, and axillae are free of any changes.

A fine pink rash is seen in the glabella, extending into both brows. Similar areas of focal scaling on pink bases are also noted in the beard area and in both external auditory meati.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is the way seborrheic dermatitis (SD) acts: It sits around for years, causing minor problems in common areas (eg, face, scalp, ears, and beard). Then the stress of life intrudes, the candle is being burnt from both ends, and SD blossoms, appearing in places such as the chest, groin, suprapubic area, axillae, and genitals.

On the genitals, SD is often bright red, with little if any scale. Why? The moisture and friction particular to the genital and intertriginous (skin on skin) areas prevent scale from accumulating.

Penile rashes generally get everyone’s attention, including that of the patient’s sexual partner(s). For the average nonclinician, the list of possible explanations is infinite—and worrisome. The situation is, in some ways, worse for the average primary care provider, who will almost always decree such a rash a “yeast infection” (though it seldom responds to anti-yeast medications—for good reason: Otherwise healthy circumcised men almost never develop yeast infections anywhere, let alone on the penis).

If you remove “yeast” from the differential, the average primary care provider will be lost. An abbreviated differential list for penile rashes and conditions includes:

• Psoriasis

• Seborrhea

• Contact vs irritant dermatitis

• Eczema/lichen simplex chronicus

• Lichen sclerosis et atrophicus (traditionally termed balanitis xerotica obliterans or BXO when it occurs on the penis)

• Lichen planus

• Reiter syndrome

• Scabies

• Erythroplasia of Queyrat (superficial squamous cell carcinoma)

• Melanoma

• Herpes simplex

• Molluscum

• Pearly penile papules

• Tyson’s glands (prominent pilosebaceous glands on the penile shaft)

• Angiokeratoma of Fordyce

• Condyloma accuminata

• Primary syphilis chancre

• Fixed-drug eruption

(Note that while yeast is not on this list, it certainly could be considered in an uncircumcised hyperglycemic patient.)

The top five items on the list would cover 90% of patients with penile rashes. Seborrheic dermatitis is utterly common but only rarely recognized when it occurs in unusual areas (as in this case).

For this patient, I prescribed topical hydrocortisone 2.5% cream (to be applied bid to all affected areas) and advised him to shampoo the areas daily with ketoconazole-containing shampoo. But the main thing I did for him, and his wife, was provide peace of mind about all the terrible conditions he didn’t have. With treatment, his penile lesions resolved within two weeks.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is common in the scalp, on the face, and in the ears, but it can also appear on the chest, axillae, or genitals.

• Yeast infections are quite uncommon in otherwise healthy men.

• Stress is often a triggering factor with worsening SD.

• Asking about and finding corroborative areas of involvement (face, ears, brows, scalp) can help in diagnosing atypical cases of SD.

Postop Patient Reports “Wound Infection”

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

A week ago, a 56-year-old man had a skin cancer surgically removed. Last night, he presented to an urgent care clinic for evaluation of a “wound infection” and received a prescription for double-strength trimethoprim/sulfa tablets (to be taken bid for 10 days). He is now in the dermatology office for follow-up. According to the patient, the problem manifested two days postop. There was no associated pain, only itching. The patient feels fine, with no fever or malaise, and there is no history of immunosuppression. He reports following his postop instructions well, changing his bandage daily and using triple-antibiotic ointment to dress the wound directly. The immediate peri-incisional area is indicated as the source of the problem. Surrounding the incision, which is healing well otherwise, is a sharply defined, bright pink, papulovesicular rash on a slightly edematous base. There is no tenderness on palpation, and no purulent material can be expressed from the wound. The area is only slightly warmer than the surrounding skin.

Baby Has Rash; Parents Feel Itchy

A 5-month-old baby is brought in by his parents for evaluation of a rash that manifested on his hands several weeks ago. It then spread to his arms and trunk and is now essentially everywhere except his face. Despite a number of treatment attempts, including use of oral antibiotics (cephalexin suspension 125/5 cc) and OTC topical steroid creams, the problem has persisted.

Prior to dermatology, they had consulted a pediatrician. He suggested the child might have scabies, for which he prescribed permethrin cream. The parents tried it, but it made little if any difference.

Neither the child nor his parents are atopic. However, both parents have recently started to feel itchy.

EXAMINATION

The child is afebrile and in no acute distress. Hundreds of tiny papules are scattered on his trunk, arms, and legs, with a particular concentration on his palms. Several of the papules, on closer examination, prove to be vesicles (ie, filled with clear fluid).

One of these lesions, on the child’s volar wrist, is scraped and the sample examined under the microscope. Magnification at 10x power reveals an adult scabies organism and a number of rugby ball–shaped eggs.

Both parents are also examined and found to have probable scabies as well. The mother’s lesions are concentrated around the anterior axillary areas and waistline. The father’s are on his volar wrists and penis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates several issues revolving around the diagnosis of scabies. One might think this would be a simple matter: Diagnose, then treat. Alas, it is seldom so.

For one thing, the diagnosis of scabies needs to be confirmed, whenever possible, with microscopic findings of scabetic elements. Without this, patient and provider confidence are lacking—a situation that often leads to shotgun treatment.

In addition, had the diagnosis been confirmed prior to presentation to dermatology, the previously consulted providers might have considered treating the whole family and trying to identify the source of the infestation. Both of these are absolutely crucial to successful treatment.

Several factors make the diagnosis of scabies difficult in infants. Any part of an infant’s thin, soft, relatively hairless skin is fair game (whereas, in adults, scabies rarely affects skin above the neck). Furthermore, although infants with scabies undoubtedly itch—probably just as much as adults—they are totally inept excoriators and even worse historians. In contrast, adults with scabies will scratch continuously while in the exam room and complain bitterly 24/7.

Once the diagnosis is established, a crucial element of dealing effectively with scabies is education—in this case, of the parents. They must understand the nature of the problem in specific terms. For example, scabies cannot be caught from or given to nonhuman hosts (eg, animals). And while I advise affected families to clean areas such as beds, sofas, and bathrooms, I also emphasize that the organism does not reside in or multiply on inanimate objects. Despite my best efforts, though, some families become almost hysterical: steam-cleaning every surface, calling pest control, washing bedding and towels multiple times, and calling me three times a day.

Families must also understand that treatment of all household members must be coordinated and done twice, seven to 10 days apart, in order to kill freshly hatched organisms. This child was treated with permethrin 5% cream, applied to the entire body and left on overnight, then washed off the next morning (twice per the schedule outlined above). In addition to permethrin, the adults were treated with ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) on the same schedule. Even with these extensive measures, recurrence would not be surprising.

Most often, when treatment “fails,” it is because the diagnosis was not scabies in the first place. In confirmed cases, treatment will be unsuccessful if all family members are not adequately (and concurrently) treated. Another problem occurs when the actual source is outside the home (daycare, sleepovers, sexual partner) and remains unidentified—dooming the family to recurrence. (Institutional scabies—from nursing homes, group living, etc—can be far more difficult to deal with and is beyond the scope of this article.)

The differential for scabies includes—most significantly—atopic dermatitis, which it can closely resemble.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Scabies can show up almost anywhere on an infant’s body, because the skin is so thin, hairless, and soft.

• If the baby has scabies, chances are the parents and siblings have it too.

• Someone brings scabies into the family, and unless the source is identified and treated, the problem will recur.

• Microscopic examination (KOH) for scabetic elements is a crucial component of diagnosis and treatment.

• Scabies sarcoptes var humani is species-specific and cannot be given to or caught from an animal.

• Permethrin cream 5% is considered safe for infants ages 2 months and older.

A 5-month-old baby is brought in by his parents for evaluation of a rash that manifested on his hands several weeks ago. It then spread to his arms and trunk and is now essentially everywhere except his face. Despite a number of treatment attempts, including use of oral antibiotics (cephalexin suspension 125/5 cc) and OTC topical steroid creams, the problem has persisted.

Prior to dermatology, they had consulted a pediatrician. He suggested the child might have scabies, for which he prescribed permethrin cream. The parents tried it, but it made little if any difference.

Neither the child nor his parents are atopic. However, both parents have recently started to feel itchy.

EXAMINATION

The child is afebrile and in no acute distress. Hundreds of tiny papules are scattered on his trunk, arms, and legs, with a particular concentration on his palms. Several of the papules, on closer examination, prove to be vesicles (ie, filled with clear fluid).

One of these lesions, on the child’s volar wrist, is scraped and the sample examined under the microscope. Magnification at 10x power reveals an adult scabies organism and a number of rugby ball–shaped eggs.

Both parents are also examined and found to have probable scabies as well. The mother’s lesions are concentrated around the anterior axillary areas and waistline. The father’s are on his volar wrists and penis.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates several issues revolving around the diagnosis of scabies. One might think this would be a simple matter: Diagnose, then treat. Alas, it is seldom so.

For one thing, the diagnosis of scabies needs to be confirmed, whenever possible, with microscopic findings of scabetic elements. Without this, patient and provider confidence are lacking—a situation that often leads to shotgun treatment.