User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Apply now for the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence positions

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2019–2021 Clinical Scholar in Residence positions. Applications are due April 1.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence Program is a two-year on-site fellowship in surgical outcomes research, health services research, and health care policy. It was initiated in 2005 to advance the College’s quality improvement initiatives and to offer opportunities for residents to work on ACS Quality Programs. More specifically, ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence perform research relevant to ongoing projects in the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care.

About the program

The primary objective of the fellowship is to address issues in health care quality, health policy, and patient safety, with the goal of helping the ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence prepare for a research career in academic surgery. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have worked on projects and research using data from the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, the National Cancer Database, the National Trauma Data Bank®, the Surgeon Specific Registry, and the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program and have been involved in guideline development and accreditation programs. Scholars are assigned to the appropriate group within the ACS based on their interests and the College’s needs.

In addition, participants earn a master’s degree in health services and outcomes research or health care quality and patient safety during their two years at the ACS headquarters in Chicago, IL. The goal of this aspect of the program is to educate clinicians to become effective researchers in health care services and outcomes. The health services and outcomes research curriculum focuses on these issues within institutional and health care delivery systems, as well as in the external environment that shapes health policy centered on quality and safety issues.

The program takes approximately two years to complete. All coursework is done at Northwestern University’s downtown Chicago campus, one block from the ACS headquarters. The ACS also offers a variety of educational programs from which the Clinical Scholars may benefit, including the Outcomes Research Course and the Clinical Trials Course.

The ACS assigns internal mentors to meet regularly with each ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence. Scholars also have opportunities to interact with various surgeons who are affiliated with the ACS and the Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care. Mentorship is one of the most important aspects of this fellowship. Guidance and interaction with multiple individuals from diverse backgrounds will provide the best opportunity for success. In addition, a core of ACS staff statisticians and project analysts serve as invaluable resources to the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence.

Past successes

Since its inception, surgical residents from throughout the U.S., including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, and Ohio, have participated in the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence program. These individuals report excellent, productive experiences that have been useful in launching their careers in the field of academic surgery. In all, 16 scholars have completed the program and five scholars are currently participating. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have demonstrated great dedication to outcomes research and the improvement of the quality of surgical care.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have presented their findings at national meetings and in high-impact, peer-reviewed publications, in addition to having contributed a great deal to the ACS Quality Programs. Furthermore, scholars have gone on to gain prestigious fellowships in several fields, including surgical oncology and pediatric surgery.

Apply now

The 2019–2021 scholars will begin their work July 1, 2019. Applications for these positions are due by April 1, 2018. Applicants are required to have funding from their institution or other grant mechanism.

For more information about the program and the application requirements, go to facs.org/clinicalscholars, or send an e-mail to [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2019–2021 Clinical Scholar in Residence positions. Applications are due April 1.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence Program is a two-year on-site fellowship in surgical outcomes research, health services research, and health care policy. It was initiated in 2005 to advance the College’s quality improvement initiatives and to offer opportunities for residents to work on ACS Quality Programs. More specifically, ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence perform research relevant to ongoing projects in the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care.

About the program

The primary objective of the fellowship is to address issues in health care quality, health policy, and patient safety, with the goal of helping the ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence prepare for a research career in academic surgery. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have worked on projects and research using data from the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, the National Cancer Database, the National Trauma Data Bank®, the Surgeon Specific Registry, and the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program and have been involved in guideline development and accreditation programs. Scholars are assigned to the appropriate group within the ACS based on their interests and the College’s needs.

In addition, participants earn a master’s degree in health services and outcomes research or health care quality and patient safety during their two years at the ACS headquarters in Chicago, IL. The goal of this aspect of the program is to educate clinicians to become effective researchers in health care services and outcomes. The health services and outcomes research curriculum focuses on these issues within institutional and health care delivery systems, as well as in the external environment that shapes health policy centered on quality and safety issues.

The program takes approximately two years to complete. All coursework is done at Northwestern University’s downtown Chicago campus, one block from the ACS headquarters. The ACS also offers a variety of educational programs from which the Clinical Scholars may benefit, including the Outcomes Research Course and the Clinical Trials Course.

The ACS assigns internal mentors to meet regularly with each ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence. Scholars also have opportunities to interact with various surgeons who are affiliated with the ACS and the Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care. Mentorship is one of the most important aspects of this fellowship. Guidance and interaction with multiple individuals from diverse backgrounds will provide the best opportunity for success. In addition, a core of ACS staff statisticians and project analysts serve as invaluable resources to the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence.

Past successes

Since its inception, surgical residents from throughout the U.S., including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, and Ohio, have participated in the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence program. These individuals report excellent, productive experiences that have been useful in launching their careers in the field of academic surgery. In all, 16 scholars have completed the program and five scholars are currently participating. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have demonstrated great dedication to outcomes research and the improvement of the quality of surgical care.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have presented their findings at national meetings and in high-impact, peer-reviewed publications, in addition to having contributed a great deal to the ACS Quality Programs. Furthermore, scholars have gone on to gain prestigious fellowships in several fields, including surgical oncology and pediatric surgery.

Apply now

The 2019–2021 scholars will begin their work July 1, 2019. Applications for these positions are due by April 1, 2018. Applicants are required to have funding from their institution or other grant mechanism.

For more information about the program and the application requirements, go to facs.org/clinicalscholars, or send an e-mail to [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is now accepting applications for the 2019–2021 Clinical Scholar in Residence positions. Applications are due April 1.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence Program is a two-year on-site fellowship in surgical outcomes research, health services research, and health care policy. It was initiated in 2005 to advance the College’s quality improvement initiatives and to offer opportunities for residents to work on ACS Quality Programs. More specifically, ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence perform research relevant to ongoing projects in the ACS Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care.

About the program

The primary objective of the fellowship is to address issues in health care quality, health policy, and patient safety, with the goal of helping the ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence prepare for a research career in academic surgery. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have worked on projects and research using data from the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, the National Cancer Database, the National Trauma Data Bank®, the Surgeon Specific Registry, and the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program and have been involved in guideline development and accreditation programs. Scholars are assigned to the appropriate group within the ACS based on their interests and the College’s needs.

In addition, participants earn a master’s degree in health services and outcomes research or health care quality and patient safety during their two years at the ACS headquarters in Chicago, IL. The goal of this aspect of the program is to educate clinicians to become effective researchers in health care services and outcomes. The health services and outcomes research curriculum focuses on these issues within institutional and health care delivery systems, as well as in the external environment that shapes health policy centered on quality and safety issues.

The program takes approximately two years to complete. All coursework is done at Northwestern University’s downtown Chicago campus, one block from the ACS headquarters. The ACS also offers a variety of educational programs from which the Clinical Scholars may benefit, including the Outcomes Research Course and the Clinical Trials Course.

The ACS assigns internal mentors to meet regularly with each ACS Clinical Scholar in Residence. Scholars also have opportunities to interact with various surgeons who are affiliated with the ACS and the Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care. Mentorship is one of the most important aspects of this fellowship. Guidance and interaction with multiple individuals from diverse backgrounds will provide the best opportunity for success. In addition, a core of ACS staff statisticians and project analysts serve as invaluable resources to the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence.

Past successes

Since its inception, surgical residents from throughout the U.S., including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, and Ohio, have participated in the ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence program. These individuals report excellent, productive experiences that have been useful in launching their careers in the field of academic surgery. In all, 16 scholars have completed the program and five scholars are currently participating. The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have demonstrated great dedication to outcomes research and the improvement of the quality of surgical care.

The ACS Clinical Scholars in Residence have presented their findings at national meetings and in high-impact, peer-reviewed publications, in addition to having contributed a great deal to the ACS Quality Programs. Furthermore, scholars have gone on to gain prestigious fellowships in several fields, including surgical oncology and pediatric surgery.

Apply now

The 2019–2021 scholars will begin their work July 1, 2019. Applications for these positions are due by April 1, 2018. Applicants are required to have funding from their institution or other grant mechanism.

For more information about the program and the application requirements, go to facs.org/clinicalscholars, or send an e-mail to [email protected].

ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC year-end update

The American College of Surgeons Professional Association (ACSPA) and members of its political action committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) provide nonpartisan financial support to federal lawmakers and individuals seeking office who share surgery’s perspective on health care policy issues and are well-positioned to advocate for surgery’s legislative goals. As of press time, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC raised more than $500,000 from more than 1,200 ACSPA members and staff, and disbursed more than $380,000 to more than 100 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees.

Following are SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement highlights:

• Willens Society ($25,000 or more over 10 years): 12

• Elite Donors ($2,500–$5,000): 23

• High Donors ($500–$2,499): 372

• General Donors ($100–$499): 669

• Top ACS leadership groups with 100 percent participation: Regents and Officers, Health Policy Advisory Council, Health Policy and Advocacy Group, and SurgeonsPAC Board of Directors

• Top five specialties: General, pediatric, vascular, colorectal, and plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Top states: Texas, California, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania

• Contributions disbursed in line with Congressional party ratios—58 percent to Republicans and 42 percent to Democrats

• Attended/hosted more than 200 health care industry events

• Organized eight physician community events for key surgical champions in Congress

• Facilitated more than 30 in-district check deliveries

• Supported 12 physician candidates

In addition, SurgeonsPAC co-hosted the eighth annual Specialty Physician and Dentist Candidate Workshop and 10th annual Medical and Dental PAC Forum.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement activities, contact SurgeonsPAC staff at [email protected] or 202-672-1520.

Note

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of the ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal Law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nationals. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA, and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals who contribute more than $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(6) of the Internal Revenue Service.

The American College of Surgeons Professional Association (ACSPA) and members of its political action committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) provide nonpartisan financial support to federal lawmakers and individuals seeking office who share surgery’s perspective on health care policy issues and are well-positioned to advocate for surgery’s legislative goals. As of press time, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC raised more than $500,000 from more than 1,200 ACSPA members and staff, and disbursed more than $380,000 to more than 100 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees.

Following are SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement highlights:

• Willens Society ($25,000 or more over 10 years): 12

• Elite Donors ($2,500–$5,000): 23

• High Donors ($500–$2,499): 372

• General Donors ($100–$499): 669

• Top ACS leadership groups with 100 percent participation: Regents and Officers, Health Policy Advisory Council, Health Policy and Advocacy Group, and SurgeonsPAC Board of Directors

• Top five specialties: General, pediatric, vascular, colorectal, and plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Top states: Texas, California, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania

• Contributions disbursed in line with Congressional party ratios—58 percent to Republicans and 42 percent to Democrats

• Attended/hosted more than 200 health care industry events

• Organized eight physician community events for key surgical champions in Congress

• Facilitated more than 30 in-district check deliveries

• Supported 12 physician candidates

In addition, SurgeonsPAC co-hosted the eighth annual Specialty Physician and Dentist Candidate Workshop and 10th annual Medical and Dental PAC Forum.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement activities, contact SurgeonsPAC staff at [email protected] or 202-672-1520.

Note

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of the ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal Law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nationals. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA, and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals who contribute more than $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(6) of the Internal Revenue Service.

The American College of Surgeons Professional Association (ACSPA) and members of its political action committee (ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC) provide nonpartisan financial support to federal lawmakers and individuals seeking office who share surgery’s perspective on health care policy issues and are well-positioned to advocate for surgery’s legislative goals. As of press time, the ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC raised more than $500,000 from more than 1,200 ACSPA members and staff, and disbursed more than $380,000 to more than 100 congressional candidates, leadership PACs, and political campaign committees.

Following are SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement highlights:

• Willens Society ($25,000 or more over 10 years): 12

• Elite Donors ($2,500–$5,000): 23

• High Donors ($500–$2,499): 372

• General Donors ($100–$499): 669

• Top ACS leadership groups with 100 percent participation: Regents and Officers, Health Policy Advisory Council, Health Policy and Advocacy Group, and SurgeonsPAC Board of Directors

• Top five specialties: General, pediatric, vascular, colorectal, and plastic and reconstructive surgery

• Top states: Texas, California, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania

• Contributions disbursed in line with Congressional party ratios—58 percent to Republicans and 42 percent to Democrats

• Attended/hosted more than 200 health care industry events

• Organized eight physician community events for key surgical champions in Congress

• Facilitated more than 30 in-district check deliveries

• Supported 12 physician candidates

In addition, SurgeonsPAC co-hosted the eighth annual Specialty Physician and Dentist Candidate Workshop and 10th annual Medical and Dental PAC Forum.

To learn more about SurgeonsPAC fundraising and disbursement activities, contact SurgeonsPAC staff at [email protected] or 202-672-1520.

Note

Contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC are not deductible as charitable contributions for federal income tax purposes. Contributions are voluntary, and all members of the ACSPA have the right to refuse to contribute without reprisal. Federal Law prohibits ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC from accepting contributions from foreign nationals. By law, if your contributions are made using a personal check or credit card, ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC may only use your contribution to support candidates in federal elections. All corporate contributions to ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC will be used for educational and administrative fees of ACSPA, and other activities permissible under federal law. Federal law requires ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC to use its best efforts to collect and report the name, mailing address, occupation, and the name of the employer of individuals who contribute more than $200 in a calendar year. ACSPA-SurgeonsPAC is a program of the ACSPA which is exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(6) of the Internal Revenue Service.

Nominations for Board of Regents, Officers-Elect due February 23

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) 2018 Nominating Committee of the Fellows (NCF) and the Nominating Committee of the Board of Governors (NCBG) will be selecting nominees for leadership positions in the College.

The 2018 NCF will select nominees for the three Officer-Elect positions of the ACS:

• President-Elect

• First Vice-President-Elect

• Second Vice-President-Elect

The 2018 NCBG will select nominees for pending vacancies on the Board of Regents to be filled at Clinical Congress 2018. Nominations are open to surgeons of all specialties, but particular consideration will be given this nomination cycle to those in the following specialties:

• Burn and critical care surgery

• Gastrointestinal surgery

• General surgery

• Surgical oncology

• Transplantation

• Trauma

• Vascular surgery

For information only, the members of the Board of Regents who will be considered for reelection in 2018 are (all MD, FACS) John L. D. Atkinson, James C. Denneny III, Timothy J. Eberlein, Henri R. Ford, Enrique Hernandez, L. Scott Levin, Linda Phillips, Anton A. Sidawy, Beth H. Sutton, and Steven D. Wexner.

Visit the Bulletin website at http://bit.ly/2l69j2Y for a list of criteria for each nominating committee, as well as further details on how to submit a nomination and the nomination process. The deadline for submitting nominations is February 23, 2018.

Nominations may be submitted to [email protected]. If you have any questions, contact Emily Kalata, Staff Liaison for the NCF and NCBG, at 312-202-5360 or [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) 2018 Nominating Committee of the Fellows (NCF) and the Nominating Committee of the Board of Governors (NCBG) will be selecting nominees for leadership positions in the College.

The 2018 NCF will select nominees for the three Officer-Elect positions of the ACS:

• President-Elect

• First Vice-President-Elect

• Second Vice-President-Elect

The 2018 NCBG will select nominees for pending vacancies on the Board of Regents to be filled at Clinical Congress 2018. Nominations are open to surgeons of all specialties, but particular consideration will be given this nomination cycle to those in the following specialties:

• Burn and critical care surgery

• Gastrointestinal surgery

• General surgery

• Surgical oncology

• Transplantation

• Trauma

• Vascular surgery

For information only, the members of the Board of Regents who will be considered for reelection in 2018 are (all MD, FACS) John L. D. Atkinson, James C. Denneny III, Timothy J. Eberlein, Henri R. Ford, Enrique Hernandez, L. Scott Levin, Linda Phillips, Anton A. Sidawy, Beth H. Sutton, and Steven D. Wexner.

Visit the Bulletin website at http://bit.ly/2l69j2Y for a list of criteria for each nominating committee, as well as further details on how to submit a nomination and the nomination process. The deadline for submitting nominations is February 23, 2018.

Nominations may be submitted to [email protected]. If you have any questions, contact Emily Kalata, Staff Liaison for the NCF and NCBG, at 312-202-5360 or [email protected].

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) 2018 Nominating Committee of the Fellows (NCF) and the Nominating Committee of the Board of Governors (NCBG) will be selecting nominees for leadership positions in the College.

The 2018 NCF will select nominees for the three Officer-Elect positions of the ACS:

• President-Elect

• First Vice-President-Elect

• Second Vice-President-Elect

The 2018 NCBG will select nominees for pending vacancies on the Board of Regents to be filled at Clinical Congress 2018. Nominations are open to surgeons of all specialties, but particular consideration will be given this nomination cycle to those in the following specialties:

• Burn and critical care surgery

• Gastrointestinal surgery

• General surgery

• Surgical oncology

• Transplantation

• Trauma

• Vascular surgery

For information only, the members of the Board of Regents who will be considered for reelection in 2018 are (all MD, FACS) John L. D. Atkinson, James C. Denneny III, Timothy J. Eberlein, Henri R. Ford, Enrique Hernandez, L. Scott Levin, Linda Phillips, Anton A. Sidawy, Beth H. Sutton, and Steven D. Wexner.

Visit the Bulletin website at http://bit.ly/2l69j2Y for a list of criteria for each nominating committee, as well as further details on how to submit a nomination and the nomination process. The deadline for submitting nominations is February 23, 2018.

Nominations may be submitted to [email protected]. If you have any questions, contact Emily Kalata, Staff Liaison for the NCF and NCBG, at 312-202-5360 or [email protected].

ACS and MacLean Center offer fellowships in surgical ethics

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Education is offering fellowships in surgical ethics with the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, IL. The MacLean Center will prepare two surgeons for careers that combine clinical surgery with scholarly studies in surgical ethics beginning with a five-week, full-time course in Chicago in July and August 2018. From September 2018 to June 2019, fellowship recipients will meet weekly for a structured ethics curriculum. In addition, fellows will participate in an ethics consultation service and complete a research project. For additional information about this fellowship, contact Patrice Gabler Blair, MPH, Associate Director, ACS Division of Education, at [email protected].

Application materials are due March 1, 2018.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Education is offering fellowships in surgical ethics with the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, IL. The MacLean Center will prepare two surgeons for careers that combine clinical surgery with scholarly studies in surgical ethics beginning with a five-week, full-time course in Chicago in July and August 2018. From September 2018 to June 2019, fellowship recipients will meet weekly for a structured ethics curriculum. In addition, fellows will participate in an ethics consultation service and complete a research project. For additional information about this fellowship, contact Patrice Gabler Blair, MPH, Associate Director, ACS Division of Education, at [email protected].

Application materials are due March 1, 2018.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Division of Education is offering fellowships in surgical ethics with the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, IL. The MacLean Center will prepare two surgeons for careers that combine clinical surgery with scholarly studies in surgical ethics beginning with a five-week, full-time course in Chicago in July and August 2018. From September 2018 to June 2019, fellowship recipients will meet weekly for a structured ethics curriculum. In addition, fellows will participate in an ethics consultation service and complete a research project. For additional information about this fellowship, contact Patrice Gabler Blair, MPH, Associate Director, ACS Division of Education, at [email protected].

Application materials are due March 1, 2018.

16 cancer care facilities receive CoC Outstanding Achievement Award

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its mid-year 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria are based on qualitative and quantitative surveys conducted in the first half of 2017. A list of these award-winning cancer programs is available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-1.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to fulfill the following goals:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality care resources to other cancer programs

“More and more, we’re finding that patients and their families want to know how the health care institutions in their communities compare with one another,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “They want access to information in terms of who’s providing the best quality of care, and they want to know about overall patient outcomes. Through this recognition program, I’d like to think we’re playing a small but vital role in helping them make informed decisions on their cancer care.”

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 6 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC January 1–June 30, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” added Dr. Shulman.

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its mid-year 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria are based on qualitative and quantitative surveys conducted in the first half of 2017. A list of these award-winning cancer programs is available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-1.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to fulfill the following goals:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality care resources to other cancer programs

“More and more, we’re finding that patients and their families want to know how the health care institutions in their communities compare with one another,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “They want access to information in terms of who’s providing the best quality of care, and they want to know about overall patient outcomes. Through this recognition program, I’d like to think we’re playing a small but vital role in helping them make informed decisions on their cancer care.”

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 6 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC January 1–June 30, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” added Dr. Shulman.

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its mid-year 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria are based on qualitative and quantitative surveys conducted in the first half of 2017. A list of these award-winning cancer programs is available at www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-1.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to fulfill the following goals:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality care resources to other cancer programs

“More and more, we’re finding that patients and their families want to know how the health care institutions in their communities compare with one another,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “They want access to information in terms of who’s providing the best quality of care, and they want to know about overall patient outcomes. Through this recognition program, I’d like to think we’re playing a small but vital role in helping them make informed decisions on their cancer care.”

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 6 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC January 1–June 30, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” added Dr. Shulman.

Applications for Jacobson Award accepted through February 23

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is accepting applications for the 2018 Joan L. and Julius H. Jacobson II Promising Investigator Award (JPIA) through February 23.

The JPIA was established to recognize outstanding surgeons who are engaging in research, advancing the art and science of surgery, and demonstrating early promise of significant contribution to the practice of surgery and the safety of surgical patients. The award is supported through a generous endowed fund established by the donors and administered by the ACS Surgical Research Committee.

Award criteria

The criteria for selection of the JPIA winner are as follows:

• Candidate must be a Fellow or an Associate Fellow of the ACS.

• Candidate must be board certified in a surgical specialty and must have completed surgical training, including fellowship, in the last six years, excluding military, medical, or family leave.

• Candidate must hold a faculty appointment at a research-based academic medical center or hold a military service position.

• Candidate must have received peer-reviewed funding, such as a K-series award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Veterans Administration, National Science Foundation, or U.S. Department of Defense merit review award to support their research effort. Surgeon-scientists who are well established (for example, recipients of NIH R01 and Veterans Affairs Merit grants or equivalent grants from other agencies) are ineligible.

• Only one application per surgical department will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation must include a one-page essay to the committee explaining why the candidate should be considered for the award and that describes the importance of their past and current research.

• Nomination documentation must include copies of the candidate’s three most significant publications from their current faculty position.

• Nomination documentation must include a letter of recommendation from the candidate’s department chair. Up to three additional letters of recommendation will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation includes an NIH-formatted biographical sketch though the electronic application system.

Special consideration will be given to surgeons who are at the “tipping point” of their research careers, with a track record indicative of early promise and potential (for example, a degree program in research or a K-award).

To be considered for the award in 2018, applications must be submitted to facs.org/jpia on or before February 23, 2018.

Additional details

For more information about the award, go to facs.org/jpia.

See a list of all past recipients at facs.org/quality-programs/about/cqi/jacobson/past-recipients.

Send comments and inquiries to Jorge Hernandez, Project Coordinator, Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care—Continuous Quality Improvement, at [email protected] or call 331-202-5319.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is accepting applications for the 2018 Joan L. and Julius H. Jacobson II Promising Investigator Award (JPIA) through February 23.

The JPIA was established to recognize outstanding surgeons who are engaging in research, advancing the art and science of surgery, and demonstrating early promise of significant contribution to the practice of surgery and the safety of surgical patients. The award is supported through a generous endowed fund established by the donors and administered by the ACS Surgical Research Committee.

Award criteria

The criteria for selection of the JPIA winner are as follows:

• Candidate must be a Fellow or an Associate Fellow of the ACS.

• Candidate must be board certified in a surgical specialty and must have completed surgical training, including fellowship, in the last six years, excluding military, medical, or family leave.

• Candidate must hold a faculty appointment at a research-based academic medical center or hold a military service position.

• Candidate must have received peer-reviewed funding, such as a K-series award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Veterans Administration, National Science Foundation, or U.S. Department of Defense merit review award to support their research effort. Surgeon-scientists who are well established (for example, recipients of NIH R01 and Veterans Affairs Merit grants or equivalent grants from other agencies) are ineligible.

• Only one application per surgical department will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation must include a one-page essay to the committee explaining why the candidate should be considered for the award and that describes the importance of their past and current research.

• Nomination documentation must include copies of the candidate’s three most significant publications from their current faculty position.

• Nomination documentation must include a letter of recommendation from the candidate’s department chair. Up to three additional letters of recommendation will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation includes an NIH-formatted biographical sketch though the electronic application system.

Special consideration will be given to surgeons who are at the “tipping point” of their research careers, with a track record indicative of early promise and potential (for example, a degree program in research or a K-award).

To be considered for the award in 2018, applications must be submitted to facs.org/jpia on or before February 23, 2018.

Additional details

For more information about the award, go to facs.org/jpia.

See a list of all past recipients at facs.org/quality-programs/about/cqi/jacobson/past-recipients.

Send comments and inquiries to Jorge Hernandez, Project Coordinator, Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care—Continuous Quality Improvement, at [email protected] or call 331-202-5319.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) is accepting applications for the 2018 Joan L. and Julius H. Jacobson II Promising Investigator Award (JPIA) through February 23.

The JPIA was established to recognize outstanding surgeons who are engaging in research, advancing the art and science of surgery, and demonstrating early promise of significant contribution to the practice of surgery and the safety of surgical patients. The award is supported through a generous endowed fund established by the donors and administered by the ACS Surgical Research Committee.

Award criteria

The criteria for selection of the JPIA winner are as follows:

• Candidate must be a Fellow or an Associate Fellow of the ACS.

• Candidate must be board certified in a surgical specialty and must have completed surgical training, including fellowship, in the last six years, excluding military, medical, or family leave.

• Candidate must hold a faculty appointment at a research-based academic medical center or hold a military service position.

• Candidate must have received peer-reviewed funding, such as a K-series award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Veterans Administration, National Science Foundation, or U.S. Department of Defense merit review award to support their research effort. Surgeon-scientists who are well established (for example, recipients of NIH R01 and Veterans Affairs Merit grants or equivalent grants from other agencies) are ineligible.

• Only one application per surgical department will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation must include a one-page essay to the committee explaining why the candidate should be considered for the award and that describes the importance of their past and current research.

• Nomination documentation must include copies of the candidate’s three most significant publications from their current faculty position.

• Nomination documentation must include a letter of recommendation from the candidate’s department chair. Up to three additional letters of recommendation will be accepted.

• Nomination documentation includes an NIH-formatted biographical sketch though the electronic application system.

Special consideration will be given to surgeons who are at the “tipping point” of their research careers, with a track record indicative of early promise and potential (for example, a degree program in research or a K-award).

To be considered for the award in 2018, applications must be submitted to facs.org/jpia on or before February 23, 2018.

Additional details

For more information about the award, go to facs.org/jpia.

See a list of all past recipients at facs.org/quality-programs/about/cqi/jacobson/past-recipients.

Send comments and inquiries to Jorge Hernandez, Project Coordinator, Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care—Continuous Quality Improvement, at [email protected] or call 331-202-5319.

From the Editors: Finding joy

While basking in the fading glow of the holidays, I have been reflecting on the dynamic of combined with the negativity local and world events engender that can push us toward burnout.

The holiday season is a time when people tend to engage in activities that have been shown to improve mood and outlook: connecting with old friends, sharing memories of a happier time, spending time with children and grandchildren, sitting around a warm fire, enjoying the sights and smells of bright decorations and fragrant candles, attending traditional holiday plays, concerts, and ballets. The holiday traditions, no matter what your ethnic or religious background, create community and warm feelings. The workweek may be shortened, people take a little time out, smile a bit more. For many of us, these activities can be a tonic.

At the same time, the days become shorter, colder, and grayer in most of North America. The normal frustrations of our day-to-day professional lives may seem more profound during the winter, and some experience SAD (seasonal affective disorder) or even burnout.

If we are not affected by these events, we may be missing the compassion gene. But I would suggest that an acute awareness of a world of trouble around us compounded with our own heavy load as surgeons is a recipe for burnout. It may not be within the capacity of any of us to alter the reality of our present world, and the surgical profession is not going to become a low-key occupation any time soon. But we can control our response to all this and take steps to attend our own emotional health.

I have found that the single most effective measure to combat negative feelings is to connect with colleagues, friends, and family to share positive, enjoyable experiences: a potluck dinner, a concert, a hike (or snowshoe trip) in the woods. We should seek out optimistic, glass-half-full individuals. We all have some of these folks in our lives and they do us a world of good.

With regard to professional stressors, reaching out to colleagues to work together in identifying remedies for a dysfunctional workplace may not only address the problem, but also allow you to recognize that you are not alone in your distress. Joining forces as a team to forge a solution can be satisfying and empowering.

Nevertheless, surgical practice remains intense, stressful, and demanding. As surgeons, we tend to be perfectionists, wanting to dot every “i” and cross every “t,” no matter how trivial. It is critical to set realistic expectations for how much you can achieve. Identify and prioritize personal and professional goals, make the most important goals take front and center, and delegate (or just allow to disappear) items that are less important. This may be the single most important strategy to avoid burnout: Prioritize what is essential and let the rest go.

A great deal has been written recently about resilience and mindfulness – facile concepts that don’t address the struggles of individuals feeling helpless and overwhelmed by the onslaught of demands on his/her time. Even though clichés about mindfulness can ring hollow, I have found that taking small steps to build my own inner reserves can help.

Here is my advice: Take a moment several times a day to appreciate something beautiful around you: a textured sky, a peaceful field, city lights, a nearby river with the ripples of wind on the water. Smile and greet someone on the street or in the hallway at work. Say a good word to someone on a job nicely done. Reflect on how doing these things affect you. Do they make you feel calmer and happier? “Rest your brain” every 2 hours for just a minute or two; cognitive fatigue occurs after 60-90 minutes and drains your energy if the “pause button” isn’t pushed.

Many of us neglect our personal health. It goes without saying that we are all far more likely to avoid burnout if we have a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and some exercise. We should all have a primary care provider for regular checkups and preventive exams. We speak with great authority when we counsel our patients to do this, so what possible excuse do we have for neglecting our own health?

One of the most important habits that I cultivate to improve my own mood is to end each day reflecting on three positive things that happened that day. Amid all of the calamities that occur every day in the world, it should not be difficult for those of us who live a life of relative privilege and plenty to find positive things in our lives. A strong association has been demonstrated between a sense of thankfulness and individual happiness and contentment. As surgeons, we have a ready source of positive reinforcers – the gratitude of our patients. I have a “feel good drawer” for “thank yous.” I open that drawer and read some of those messages from grateful patients. Reflecting on how we have been able to help our patients can do us all good when we are having doubts about our professional lives.

I want to encourage all surgeons to take a little better care of themselves this year. Take some specific steps to attend to your physical and emotional health. Do some activities the only purpose of which is to rest, to reflect, and to find joy.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

While basking in the fading glow of the holidays, I have been reflecting on the dynamic of combined with the negativity local and world events engender that can push us toward burnout.

The holiday season is a time when people tend to engage in activities that have been shown to improve mood and outlook: connecting with old friends, sharing memories of a happier time, spending time with children and grandchildren, sitting around a warm fire, enjoying the sights and smells of bright decorations and fragrant candles, attending traditional holiday plays, concerts, and ballets. The holiday traditions, no matter what your ethnic or religious background, create community and warm feelings. The workweek may be shortened, people take a little time out, smile a bit more. For many of us, these activities can be a tonic.

At the same time, the days become shorter, colder, and grayer in most of North America. The normal frustrations of our day-to-day professional lives may seem more profound during the winter, and some experience SAD (seasonal affective disorder) or even burnout.

If we are not affected by these events, we may be missing the compassion gene. But I would suggest that an acute awareness of a world of trouble around us compounded with our own heavy load as surgeons is a recipe for burnout. It may not be within the capacity of any of us to alter the reality of our present world, and the surgical profession is not going to become a low-key occupation any time soon. But we can control our response to all this and take steps to attend our own emotional health.

I have found that the single most effective measure to combat negative feelings is to connect with colleagues, friends, and family to share positive, enjoyable experiences: a potluck dinner, a concert, a hike (or snowshoe trip) in the woods. We should seek out optimistic, glass-half-full individuals. We all have some of these folks in our lives and they do us a world of good.

With regard to professional stressors, reaching out to colleagues to work together in identifying remedies for a dysfunctional workplace may not only address the problem, but also allow you to recognize that you are not alone in your distress. Joining forces as a team to forge a solution can be satisfying and empowering.

Nevertheless, surgical practice remains intense, stressful, and demanding. As surgeons, we tend to be perfectionists, wanting to dot every “i” and cross every “t,” no matter how trivial. It is critical to set realistic expectations for how much you can achieve. Identify and prioritize personal and professional goals, make the most important goals take front and center, and delegate (or just allow to disappear) items that are less important. This may be the single most important strategy to avoid burnout: Prioritize what is essential and let the rest go.

A great deal has been written recently about resilience and mindfulness – facile concepts that don’t address the struggles of individuals feeling helpless and overwhelmed by the onslaught of demands on his/her time. Even though clichés about mindfulness can ring hollow, I have found that taking small steps to build my own inner reserves can help.

Here is my advice: Take a moment several times a day to appreciate something beautiful around you: a textured sky, a peaceful field, city lights, a nearby river with the ripples of wind on the water. Smile and greet someone on the street or in the hallway at work. Say a good word to someone on a job nicely done. Reflect on how doing these things affect you. Do they make you feel calmer and happier? “Rest your brain” every 2 hours for just a minute or two; cognitive fatigue occurs after 60-90 minutes and drains your energy if the “pause button” isn’t pushed.

Many of us neglect our personal health. It goes without saying that we are all far more likely to avoid burnout if we have a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and some exercise. We should all have a primary care provider for regular checkups and preventive exams. We speak with great authority when we counsel our patients to do this, so what possible excuse do we have for neglecting our own health?

One of the most important habits that I cultivate to improve my own mood is to end each day reflecting on three positive things that happened that day. Amid all of the calamities that occur every day in the world, it should not be difficult for those of us who live a life of relative privilege and plenty to find positive things in our lives. A strong association has been demonstrated between a sense of thankfulness and individual happiness and contentment. As surgeons, we have a ready source of positive reinforcers – the gratitude of our patients. I have a “feel good drawer” for “thank yous.” I open that drawer and read some of those messages from grateful patients. Reflecting on how we have been able to help our patients can do us all good when we are having doubts about our professional lives.

I want to encourage all surgeons to take a little better care of themselves this year. Take some specific steps to attend to your physical and emotional health. Do some activities the only purpose of which is to rest, to reflect, and to find joy.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

While basking in the fading glow of the holidays, I have been reflecting on the dynamic of combined with the negativity local and world events engender that can push us toward burnout.

The holiday season is a time when people tend to engage in activities that have been shown to improve mood and outlook: connecting with old friends, sharing memories of a happier time, spending time with children and grandchildren, sitting around a warm fire, enjoying the sights and smells of bright decorations and fragrant candles, attending traditional holiday plays, concerts, and ballets. The holiday traditions, no matter what your ethnic or religious background, create community and warm feelings. The workweek may be shortened, people take a little time out, smile a bit more. For many of us, these activities can be a tonic.

At the same time, the days become shorter, colder, and grayer in most of North America. The normal frustrations of our day-to-day professional lives may seem more profound during the winter, and some experience SAD (seasonal affective disorder) or even burnout.

If we are not affected by these events, we may be missing the compassion gene. But I would suggest that an acute awareness of a world of trouble around us compounded with our own heavy load as surgeons is a recipe for burnout. It may not be within the capacity of any of us to alter the reality of our present world, and the surgical profession is not going to become a low-key occupation any time soon. But we can control our response to all this and take steps to attend our own emotional health.

I have found that the single most effective measure to combat negative feelings is to connect with colleagues, friends, and family to share positive, enjoyable experiences: a potluck dinner, a concert, a hike (or snowshoe trip) in the woods. We should seek out optimistic, glass-half-full individuals. We all have some of these folks in our lives and they do us a world of good.

With regard to professional stressors, reaching out to colleagues to work together in identifying remedies for a dysfunctional workplace may not only address the problem, but also allow you to recognize that you are not alone in your distress. Joining forces as a team to forge a solution can be satisfying and empowering.

Nevertheless, surgical practice remains intense, stressful, and demanding. As surgeons, we tend to be perfectionists, wanting to dot every “i” and cross every “t,” no matter how trivial. It is critical to set realistic expectations for how much you can achieve. Identify and prioritize personal and professional goals, make the most important goals take front and center, and delegate (or just allow to disappear) items that are less important. This may be the single most important strategy to avoid burnout: Prioritize what is essential and let the rest go.

A great deal has been written recently about resilience and mindfulness – facile concepts that don’t address the struggles of individuals feeling helpless and overwhelmed by the onslaught of demands on his/her time. Even though clichés about mindfulness can ring hollow, I have found that taking small steps to build my own inner reserves can help.

Here is my advice: Take a moment several times a day to appreciate something beautiful around you: a textured sky, a peaceful field, city lights, a nearby river with the ripples of wind on the water. Smile and greet someone on the street or in the hallway at work. Say a good word to someone on a job nicely done. Reflect on how doing these things affect you. Do they make you feel calmer and happier? “Rest your brain” every 2 hours for just a minute or two; cognitive fatigue occurs after 60-90 minutes and drains your energy if the “pause button” isn’t pushed.

Many of us neglect our personal health. It goes without saying that we are all far more likely to avoid burnout if we have a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and some exercise. We should all have a primary care provider for regular checkups and preventive exams. We speak with great authority when we counsel our patients to do this, so what possible excuse do we have for neglecting our own health?

One of the most important habits that I cultivate to improve my own mood is to end each day reflecting on three positive things that happened that day. Amid all of the calamities that occur every day in the world, it should not be difficult for those of us who live a life of relative privilege and plenty to find positive things in our lives. A strong association has been demonstrated between a sense of thankfulness and individual happiness and contentment. As surgeons, we have a ready source of positive reinforcers – the gratitude of our patients. I have a “feel good drawer” for “thank yous.” I open that drawer and read some of those messages from grateful patients. Reflecting on how we have been able to help our patients can do us all good when we are having doubts about our professional lives.

I want to encourage all surgeons to take a little better care of themselves this year. Take some specific steps to attend to your physical and emotional health. Do some activities the only purpose of which is to rest, to reflect, and to find joy.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

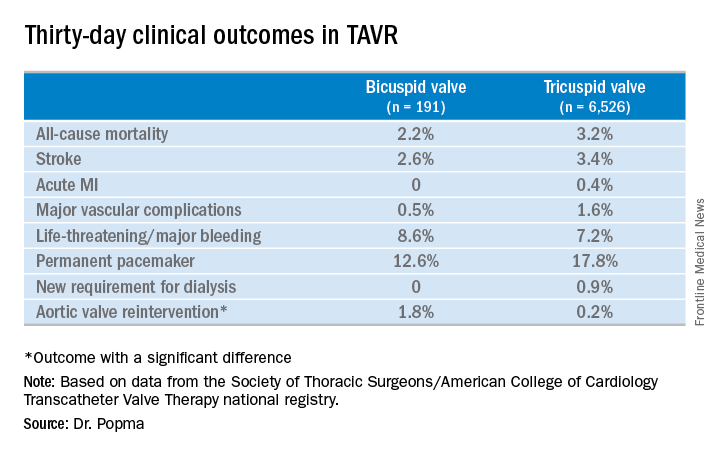

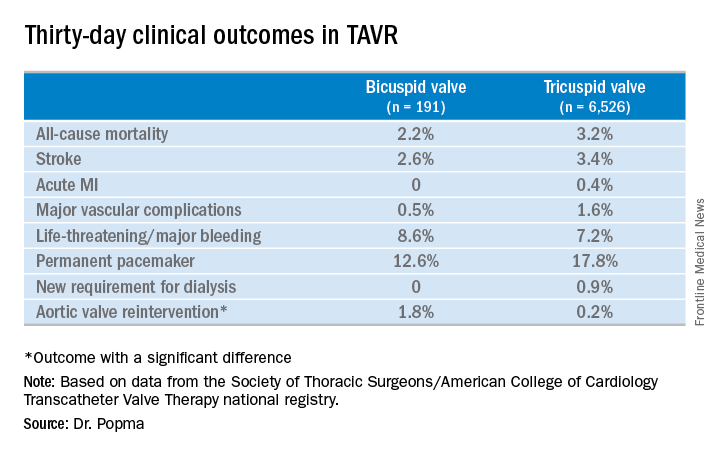

New frontier in TAVR is bicuspid disease

DENVER – Thirty-day transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) outcomes in real-world clinical practice using the Evolut R self-expanding valve were as good in patients treated for bicuspid disease as for tricuspid disease, according to a retrospective analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (STS/ACC TVT) national registry.

“I’ve always been insecure about whether we have the right technology to be able to treat bicuspid disease. This registry data is reassuring to me that we might. I think it may be time to do a prospective registry for low-surgical-risk patients with bicuspid disease and see if we can emulate these kinds of results,” said Dr. Popma, the director of interventional cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“I think that the one limitation to recruitment in our low-risk TAVR trial is patients with bicuspid disease. Probably 25%-30% of low-risk patients are bicuspid, so we can’t include them right now in our low-risk trial,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Even though TAVR for patients with bicuspid disease is off-label, operators do perform the procedure. All of these cases are captured in the STS/ACC TVT registry. Dr. Popma reported on 6,717 patients who underwent TAVR with placement of the Evolut R valve at 305 U.S. centers during 2014-2016. The purpose of this retrospective study was to compare 30-day outcomes in the 191 TAVR patients with native valve bicuspid disease with the outcomes in the 6,526 with tricuspid disease.

The two groups were evenly matched in terms of key baseline characteristics, including aortic valve mean gradient, severity of aortic, mitral, and tricuspid regurgitation, and comorbid conditions – with the exception of coronary artery disease, which was present in 48% of the bicuspid group versus 65% of those with tricuspid disease. Also, the bicuspid disease group was younger by an average of nearly 9 years, and their mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction of 52.5% was lower than the LVEF of 55.5% seen in the tricuspid group.

Procedure time averaged 126 minutes in the bicuspid group and 116 in the tricuspid group. Femoral access was utilized in 87% of the bicuspid patients and in 92% of tricuspid patients. The device was implanted successfully in 97% of the bicuspid group and in 99% of the tricuspid group. More than one valve was required in 3.7% of the bicuspid disease group, a rate similar to that in the tricuspid group. Total hospital length of stay was roughly 6 days in both groups.

Rates of symptomatic improvement at 30 days were closely similar in the two groups. Preprocedurally, two-thirds of patients in both groups had a New York Heart Association class III; at 30 days, however, that was true for a mere 2.4% of the bicuspid patients and 10.3% of the tricuspid patients. By day 30, 52% of the bicuspid group and 48% of the tricuspid group were NYHA class I.

No or only trace aortic regurgitation was present at 30 days in 62% of the bicuspid group and in 61% of the tricuspid group, while mild aortic regurgitation was noted in 31% and 33%, respectively.

Thirty-day mean aortic valve gradient improved to a similar extent in the two groups: from a baseline of 47.2 mm Hg to 9.4 mm Hg in the bicuspid group and from 42.9 mm Hg to 7.5 mm Hg in the tricuspid group.

Dr. Popma noted that an earlier analysis he carried out comparing outcomes of TAVR using the earlier-generation CoreValve in bicuspid versus tricuspid disease showed suboptimal rates of paravalvular regurgitation and an increased need for multiple valves in the bicuspid group.

“The lesson is ‘Thank God we’ve got new technology!’ because the new technology has made a big difference for us,” the cardiologist observed. “We think that the advancement in the technique and the advancement in the valves is going to give us fairly comparable outcomes with Evolut in bicuspid and tricuspid patients.”

Discussant Hasan Jilaihawi, MD, a codirector of transcatheter valve therapy at New York University, pronounced the short-term outcomes in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease “better than I would have expected,” adding that he, too, thinks it’s time for a prospective registry study of the Evolut valve in such patients.

Dr. Popma’s study was supported by Medtronic. He reported having received research grants from Medtronic and other medical device companies.

SOURCE: Popma JJ. TCT 2017.

DENVER – Thirty-day transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) outcomes in real-world clinical practice using the Evolut R self-expanding valve were as good in patients treated for bicuspid disease as for tricuspid disease, according to a retrospective analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (STS/ACC TVT) national registry.

“I’ve always been insecure about whether we have the right technology to be able to treat bicuspid disease. This registry data is reassuring to me that we might. I think it may be time to do a prospective registry for low-surgical-risk patients with bicuspid disease and see if we can emulate these kinds of results,” said Dr. Popma, the director of interventional cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“I think that the one limitation to recruitment in our low-risk TAVR trial is patients with bicuspid disease. Probably 25%-30% of low-risk patients are bicuspid, so we can’t include them right now in our low-risk trial,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Even though TAVR for patients with bicuspid disease is off-label, operators do perform the procedure. All of these cases are captured in the STS/ACC TVT registry. Dr. Popma reported on 6,717 patients who underwent TAVR with placement of the Evolut R valve at 305 U.S. centers during 2014-2016. The purpose of this retrospective study was to compare 30-day outcomes in the 191 TAVR patients with native valve bicuspid disease with the outcomes in the 6,526 with tricuspid disease.

The two groups were evenly matched in terms of key baseline characteristics, including aortic valve mean gradient, severity of aortic, mitral, and tricuspid regurgitation, and comorbid conditions – with the exception of coronary artery disease, which was present in 48% of the bicuspid group versus 65% of those with tricuspid disease. Also, the bicuspid disease group was younger by an average of nearly 9 years, and their mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction of 52.5% was lower than the LVEF of 55.5% seen in the tricuspid group.

Procedure time averaged 126 minutes in the bicuspid group and 116 in the tricuspid group. Femoral access was utilized in 87% of the bicuspid patients and in 92% of tricuspid patients. The device was implanted successfully in 97% of the bicuspid group and in 99% of the tricuspid group. More than one valve was required in 3.7% of the bicuspid disease group, a rate similar to that in the tricuspid group. Total hospital length of stay was roughly 6 days in both groups.

Rates of symptomatic improvement at 30 days were closely similar in the two groups. Preprocedurally, two-thirds of patients in both groups had a New York Heart Association class III; at 30 days, however, that was true for a mere 2.4% of the bicuspid patients and 10.3% of the tricuspid patients. By day 30, 52% of the bicuspid group and 48% of the tricuspid group were NYHA class I.

No or only trace aortic regurgitation was present at 30 days in 62% of the bicuspid group and in 61% of the tricuspid group, while mild aortic regurgitation was noted in 31% and 33%, respectively.

Thirty-day mean aortic valve gradient improved to a similar extent in the two groups: from a baseline of 47.2 mm Hg to 9.4 mm Hg in the bicuspid group and from 42.9 mm Hg to 7.5 mm Hg in the tricuspid group.

Dr. Popma noted that an earlier analysis he carried out comparing outcomes of TAVR using the earlier-generation CoreValve in bicuspid versus tricuspid disease showed suboptimal rates of paravalvular regurgitation and an increased need for multiple valves in the bicuspid group.

“The lesson is ‘Thank God we’ve got new technology!’ because the new technology has made a big difference for us,” the cardiologist observed. “We think that the advancement in the technique and the advancement in the valves is going to give us fairly comparable outcomes with Evolut in bicuspid and tricuspid patients.”

Discussant Hasan Jilaihawi, MD, a codirector of transcatheter valve therapy at New York University, pronounced the short-term outcomes in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease “better than I would have expected,” adding that he, too, thinks it’s time for a prospective registry study of the Evolut valve in such patients.

Dr. Popma’s study was supported by Medtronic. He reported having received research grants from Medtronic and other medical device companies.

SOURCE: Popma JJ. TCT 2017.

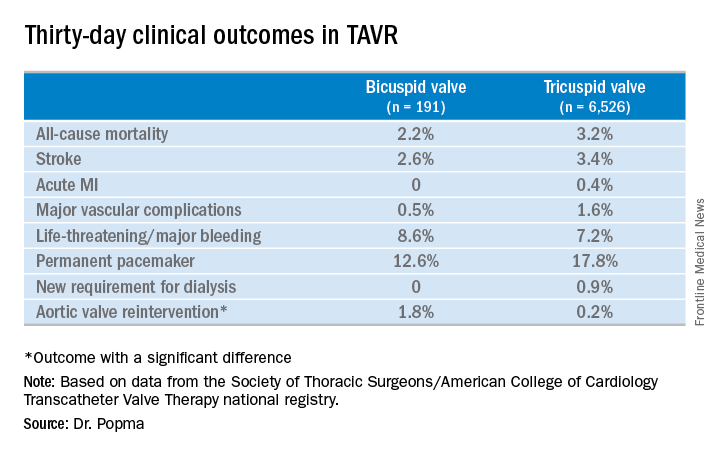

DENVER – Thirty-day transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) outcomes in real-world clinical practice using the Evolut R self-expanding valve were as good in patients treated for bicuspid disease as for tricuspid disease, according to a retrospective analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (STS/ACC TVT) national registry.

“I’ve always been insecure about whether we have the right technology to be able to treat bicuspid disease. This registry data is reassuring to me that we might. I think it may be time to do a prospective registry for low-surgical-risk patients with bicuspid disease and see if we can emulate these kinds of results,” said Dr. Popma, the director of interventional cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“I think that the one limitation to recruitment in our low-risk TAVR trial is patients with bicuspid disease. Probably 25%-30% of low-risk patients are bicuspid, so we can’t include them right now in our low-risk trial,” he added at the meeting sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Even though TAVR for patients with bicuspid disease is off-label, operators do perform the procedure. All of these cases are captured in the STS/ACC TVT registry. Dr. Popma reported on 6,717 patients who underwent TAVR with placement of the Evolut R valve at 305 U.S. centers during 2014-2016. The purpose of this retrospective study was to compare 30-day outcomes in the 191 TAVR patients with native valve bicuspid disease with the outcomes in the 6,526 with tricuspid disease.

The two groups were evenly matched in terms of key baseline characteristics, including aortic valve mean gradient, severity of aortic, mitral, and tricuspid regurgitation, and comorbid conditions – with the exception of coronary artery disease, which was present in 48% of the bicuspid group versus 65% of those with tricuspid disease. Also, the bicuspid disease group was younger by an average of nearly 9 years, and their mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction of 52.5% was lower than the LVEF of 55.5% seen in the tricuspid group.

Procedure time averaged 126 minutes in the bicuspid group and 116 in the tricuspid group. Femoral access was utilized in 87% of the bicuspid patients and in 92% of tricuspid patients. The device was implanted successfully in 97% of the bicuspid group and in 99% of the tricuspid group. More than one valve was required in 3.7% of the bicuspid disease group, a rate similar to that in the tricuspid group. Total hospital length of stay was roughly 6 days in both groups.

Rates of symptomatic improvement at 30 days were closely similar in the two groups. Preprocedurally, two-thirds of patients in both groups had a New York Heart Association class III; at 30 days, however, that was true for a mere 2.4% of the bicuspid patients and 10.3% of the tricuspid patients. By day 30, 52% of the bicuspid group and 48% of the tricuspid group were NYHA class I.

No or only trace aortic regurgitation was present at 30 days in 62% of the bicuspid group and in 61% of the tricuspid group, while mild aortic regurgitation was noted in 31% and 33%, respectively.

Thirty-day mean aortic valve gradient improved to a similar extent in the two groups: from a baseline of 47.2 mm Hg to 9.4 mm Hg in the bicuspid group and from 42.9 mm Hg to 7.5 mm Hg in the tricuspid group.

Dr. Popma noted that an earlier analysis he carried out comparing outcomes of TAVR using the earlier-generation CoreValve in bicuspid versus tricuspid disease showed suboptimal rates of paravalvular regurgitation and an increased need for multiple valves in the bicuspid group.

“The lesson is ‘Thank God we’ve got new technology!’ because the new technology has made a big difference for us,” the cardiologist observed. “We think that the advancement in the technique and the advancement in the valves is going to give us fairly comparable outcomes with Evolut in bicuspid and tricuspid patients.”

Discussant Hasan Jilaihawi, MD, a codirector of transcatheter valve therapy at New York University, pronounced the short-term outcomes in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease “better than I would have expected,” adding that he, too, thinks it’s time for a prospective registry study of the Evolut valve in such patients.

Dr. Popma’s study was supported by Medtronic. He reported having received research grants from Medtronic and other medical device companies.

SOURCE: Popma JJ. TCT 2017.

REPORTING FROM TCT 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Thirty-day clinical outcomes and symptomatic improvement were reassuringly similar both in TAVR patients who received the Evolut R valve for tricuspid disease and off-label for bicuspid disease.

Study details: This was a retrospective U.S. national registry study comparing 30-day outcomes in 191 TAVR patients with native valve bicuspid disease and 6,526 with tricuspid disease, all of whom underwent TAVR with placement of the Evolut R valve.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having received research grants from Medtronic, the study sponsor, as well as other medical device companies.

Source: Popma JJ. TCT 2017.

Vascular surgeons are top tier for burnout risk

CHICAGO – Vascular surgeons are solidly within the top tier of surgical subspecialists in terms of risk for burnout, Joan M. Anzia, MD, observed at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Joining them in this unwelcome company with an elevated rate of lower quality of life are trauma surgeons, urologists, and otolaryngologists, according to the results of a 9-year-old national study of burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons that has served as a wakeup call for the profession (Ann Surg. 2009 Sep;250[3]:463-71).

“This is where the biggest impact on burnout is going to be: institutional interventions to target the known drivers of burnout. Looking at nights on call, work compression, looking at the amount of time you guys spend in front of a computer documenting your EHR and your billing. Do you really need to do those things? You need help from midlevel professionals and others who can free you to practice at the top of your life, doing the work you love, which for most surgeons is being in the OR,” said Dr. Anzia, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and the departmental vice chair of education at Northwestern University in Chicago.

The Society for Vascular Surgery is one of many professional specialty organizations that are focusing on the burnout problem. They are joined by the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the National Academy of Medicine, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, the American Medical Association, and other interested groups.

“Since 2008, burnout rates in every specialty have increased by an average of an absolute 10%. That’s just remarkable, and it’s why people are very, very concerned,” noted the psychiatrist, who serves as the physician health liaison at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. In that capacity, she is frequently called upon to help physicians with the classic manifestations of burnout, including substance use disorders that arose as the practitioners tried to self-treat their burnout rather than seeking help.

“He reports only to the dean,” according to Dr. Anzia.

Why are vascular surgeons at such high risk for burnout? According to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the leading psychological assessment tool for burnout, the syndrome has three main components: emotional exhaustion, a sense of loss of meaning in work, and feeling ineffective in one’s work. Studies show vascular surgeons often score high in all three domains.

Vascular surgeons’ work is extremely stressful. They average 20 hours per week in the OR, and almost 3 nights on call per week. They care for acutely ill patients and perform high-intensity, high-risk procedures in which unpredictable events are common.

“Work compression – not just workload, but facing multiple demands at once that you’re trying to balance – that’s one of the key drivers of burnout, and work compression is really common in vascular surgery,” Dr. Anzia noted.

In the national surgeon burnout study, younger surgeons and those with children still living at home were at increased risk for burnout. So were surgeons whose compensation was entirely based upon the Relative Value Unit system. The number of nights on call per week was another independent risk factor.

Dr. Shanafelt and his coinvestigators found that roughly 30% of respondent surgeons screened positive for depression, and 6.4% of the study population reported having suicidal thoughts within the past 12 months.

“We lose the equivalent of two to three medical school classes worth of physicians every year to suicide. And let me tell you: 98% of those folks, at the time they suicided, had major depression, which is eminently treatable. And the reason they weren’t treated was they, like most physicians, avoided treatment. They had difficulty accessing care. They were worried about stigma, life insurance, things like that. This is a huge problem which is mostly preventable, but we are not addressing it effectively,” Dr. Anzia said.

While institutional interventions aimed at the prevention of physician burnout such as spending less time on the electronic health record will have a major impact on the problem, thought leaders in medical education have come to realize that it also will be necessary to address the broader culture of medicine.

“There are so many implicit beliefs that every one of us grew up with, like ‘I work when I’m sick,’ or ‘I can work without sleep.’ All those things that we believe make us good physicians actually may not be entirely true,” the psychiatrist said.